| Revision as of 02:51, 19 August 2010 view source97.104.46.29 (talk) →Plot← Previous edit | Revision as of 10:58, 19 August 2010 view source TaerkastUA (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Page movers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers18,626 edits Undid revision 379703698 by 97.104.46.29 (talk) irrelevant, per prior discussion.Next edit → | ||

| Line 31: | Line 31: | ||

| ==Plot== | ==Plot== | ||

| Sally Hardesty (Marilyn Burns) and her |

Sally Hardesty (Marilyn Burns) and her brother, Franklin (Paul A. Partain), travel with three friends: Jerry (Allen Danziger), Kirk (William Vail) and Pam (Teri McMinn), to a cemetery containing the grave of the Hardestys' grandfather. They aim to investigate reports of vandalism and of corpse-defilement. Afterwards, they decide to visit an old Hardesty family homestead, and on the way, the group picks up a ] (Edwin Neal). The man speaks and acts bizarrely, and then slashes himself and Franklin with a ] before the group force him out of the van. The group later stop at a gas station to refuel their vehicle, but when they find out from the proprietor (Jim Siedow) that the pumps are empty, the group continues to the homestead, intending to return to the gas station later after a fuel truck makes its delivery. Franklin tells Kirk and Pam about a local swimming hole, and the couple head off to find it. Instead, they stumble upon a nearby house, prompting Kirk to ask the residents for some gas, while Pam waits on the front steps. | ||

| After receiving no answer, but finding the door unlocked, Kirk enters the house, where Leatherface (Gunnar Hansen) suddenly appears and kills him. Pam enters soon after, finding the house filled with furniture made from human bones. She attempts to flee, but Leatherface catches her before she can escape, impaling her on a meathook. At sunset, Sally's boyfriend Jerry heads out from the old Hardesty house to look for the others. Finding the couple's blanket outside the house, he investigates and finds Pam still alive inside a freezer. Before he can react, Leatherface appears and murders him, stuffing Pam back inside the freezer afterward. | After receiving no answer, but finding the door unlocked, Kirk enters the house, where Leatherface (Gunnar Hansen) suddenly appears and kills him. Pam enters soon after, finding the house filled with furniture made from human bones. She attempts to flee, but Leatherface catches her before she can escape, impaling her on a meathook. At sunset, Sally's boyfriend Jerry heads out from the old Hardesty house to look for the others. Finding the couple's blanket outside the house, he investigates and finds Pam still alive inside a freezer. Before he can react, Leatherface appears and murders him, stuffing Pam back inside the freezer afterward. | ||

Revision as of 10:58, 19 August 2010

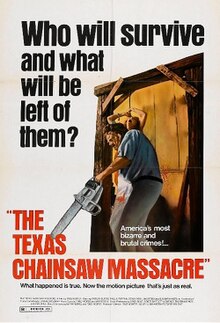

For other uses, see The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. 1974 Template:Film US film| The Texas Chain Saw Massacre | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Tobe Hooper |

| Written by | Kim Henkel Tobe Hooper |

| Produced by | Tobe Hooper Lou Peraino |

| Starring | Marilyn Burns Paul A. Partain Edwin Neal Jim Siedow Gunnar Hansen |

| Cinematography | Daniel Pearl |

| Edited by | Larry Carroll Sallye Richardson |

| Music by | Wayne Bell Tobe Hooper |

| Production companies | Vortex, Inc. |

| Distributed by | United States: Bryanston Distributing Company New Line Cinema (re-release) United Kingdom: Blue Dolphin |

| Release date | October 1, 1974 |

| Running time | 84 minutes |

| Country | Template:Film US |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $140,000 |

| Box office | $30,859,000 |

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre is a 1974 American independent horror film directed by Tobe Hooper and written collaboratively by Hooper and Kim Henkel. The film stars Marilyn Burns, Gunnar Hansen, Teri McMinn, William Vail, Edwin Neal, and Paul A. Partain. While presented as a true story involving the ambush and murder of a group of friends on a road trip in rural Texas by a family of cannibals, the film is completely fictional. The Texas Chain Saw Massacre is the first of the six films in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre film franchise, which revolve around the character of Leatherface, who is played by Hansen in this film.

In drafting his story, Hooper took into account the history of Wisconsin serial killer Ed Gein, as well as the perceived lies of the American government under the Nixon administration (1969–1974). Hooper produced the film on a budget estimated at around $140,000, and cast relatively unknown actors, drawing people mainly from the areas surrounding the Texas filming locations. Principal photography for the film took place between July 15 and August 14, 1973. When the film was completed, Hooper struggled to find a distributor willing to release it due to its graphic depiction of violence; when he eventually secured a distributor, the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) gave the film an R-rating instead of the PG-rating Hooper had intended the film to receive.

Bryanston Distributing Company released The Texas Chain Saw Massacre to cinemas on October 1, 1974. As a result of the film's content, several foreign jurisdictions banned the film. Initially, the film drew a mixed reception from critics regarding the atmosphere, story, characters and graphic content, but it became a strong commercial success, grossing $30.8 million at the U.S. box office. Despite the lack of critical unanimity, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre has gained a reputation as one of the greatest and most influential horror films in cinema history. It originated several elements common in the slasher film genre, including the characterization of the killer as a large, hulking and faceless figure and the use of power tools as murder weapons.

Plot

Sally Hardesty (Marilyn Burns) and her brother, Franklin (Paul A. Partain), travel with three friends: Jerry (Allen Danziger), Kirk (William Vail) and Pam (Teri McMinn), to a cemetery containing the grave of the Hardestys' grandfather. They aim to investigate reports of vandalism and of corpse-defilement. Afterwards, they decide to visit an old Hardesty family homestead, and on the way, the group picks up a hitchhiker (Edwin Neal). The man speaks and acts bizarrely, and then slashes himself and Franklin with a straight razor before the group force him out of the van. The group later stop at a gas station to refuel their vehicle, but when they find out from the proprietor (Jim Siedow) that the pumps are empty, the group continues to the homestead, intending to return to the gas station later after a fuel truck makes its delivery. Franklin tells Kirk and Pam about a local swimming hole, and the couple head off to find it. Instead, they stumble upon a nearby house, prompting Kirk to ask the residents for some gas, while Pam waits on the front steps.

After receiving no answer, but finding the door unlocked, Kirk enters the house, where Leatherface (Gunnar Hansen) suddenly appears and kills him. Pam enters soon after, finding the house filled with furniture made from human bones. She attempts to flee, but Leatherface catches her before she can escape, impaling her on a meathook. At sunset, Sally's boyfriend Jerry heads out from the old Hardesty house to look for the others. Finding the couple's blanket outside the house, he investigates and finds Pam still alive inside a freezer. Before he can react, Leatherface appears and murders him, stuffing Pam back inside the freezer afterward.

With darkness falling, Sally and Franklin set out to find their friends. As they near the killer's house, calling for the others, Leatherface lunges out of the darkness and murders Franklin with a chainsaw. Sally escapes to the house, only to find the desiccated remains of an elderly couple in an upstairs room. In order to escape from Leatherface, who is still pursuing her, she jumps through a second floor window and continues to flee, eventually arriving at the gas station. As she reaches it, Leatherface disappears into the night. The proprietor at first calms her with offers of help, then binds her with rope and forces her into his truck. He drives to the house, arriving at the same time as the hitchhiker, who turns out to be Leatherface's younger brother. When the pair bring Sally inside, the hitchhiker taunts her when he realizes who she is.

The men torment the bound and gagged Sally, while Leatherface, now dressed as a woman, serves dinner. Leatherface and the hitchhiker bring the old man from upstairs, still alive, to the table to join the meal. During the night, they decide Sally should be killed by "Grandpa" (John Dugan), out of respect for his work at the slaughter house when he was younger. "Grandpa" is too weak to hit Sally with a hammer, repeatedly dropping it. In the confusion, Sally breaks free, leaps through a window and escapes from the house, running out onto the road. Leatherface and the hitchhiker give chase, but the hitchhiker is run down and killed by a passing semi-trailer truck. Armed with his chainsaw, Leatherface attacks the truck when the driver stops to help, and is hit in the face with a large wrench wielded by the driver. Sally escapes in the bed of a passing pickup truck as Leatherface waves the chainsaw above his head in frustration.

Production

Development

| "I definitely studied Gein,... but I also noticed a murder case in Houston at the time, a serial murderer you probably remember named Elmer Wayne Henley. He was a young man who recruited victims for an older homosexual man. I saw some news report where Elmer Wayne... said, 'I did these crimes, and I'm gonna stand up and take it like a man". Well, that struck me as interesting, that he had this conventional morality at that point. He wanted it known that, now that he was caught, he would do the right thing. So this kind of moral schizophrenia is something I tried to build into the characters." |

| — Kim Henkel |

The concept for the film arose in the early 1970s, while Hooper worked as a college professor at the University of Texas at Austin, and as a documentary cameraman. He had already developed the idea of a film centering on the theme of isolation, as well as the woods and darkness, and pursued these themes further as he worked on the project. He also credited graphic coverage of violence by San Antonio news outlets as part of the inspiration for the film. After further development, Hooper gave the film the working titles Headcheese and Leatherface. He based the plot loosely on the murders committed by 1950s Wisconsin serial killer Ed Gein, who served as the inspiration for a number of other horror films.

With regards to the film's main influences, Hooper has cited the impact of changes in the cultural and political landscape. He directly correlates the intentional misinformation that the "film you are about to see is true" as a response to being "lied to by the government about things that were going on all over the world", including Watergate, the gasoline crisis, and "the massacres and atrocities in the Vietnam War". The additional "lack of sentimentality and the brutality of things" that Hooper noticed in watching the local news - whose coverage was graphic, "showing brains spilled all over the road" - led to his belief that "man was the real monster here, just wearing a different face, so I put a literal mask on the monster in my film". The idea for featuring a chainsaw in the film came to Hooper while in the hardware section of a busy store, as he contemplated a way to get out quickly through the crowd.

Hooper and Kim Henkel - the original writers of the screenplay - formed a corporation named Vortex, Inc., with Henkel as president and Hooper as vice president. They then asked Bill Parsley, a friend of Hooper, to provide funding for the film; Parsley formed a company named MAB, Inc. and invested $60,000 in making the film. In return, MAB owned 50 percent of the film and its profits. Production manager Ron Bozman told most of the cast and crew to defer parts of their salaries until after the movie was sold to a distributor. Vortex made the idea more attractive by awarding most of the cast and crew with a share of Vortex's potential profits, ranging from 0.25 to 6%, similar to mortgage points. Due to a miscommunication among Vortex and the others, the cast and crew were not informed that Vortex owned only 50% of the film, thereby making their points worth half of the assumed value.

The crew exceeded the original $60,000 budget for the film during the editing process, eventually spending a total of $140,000. Pie in the Sky (P.I.T.S.) donated $23,532 in exchange for 19% of Vortex's 50% share of the profits, leaving Henkel and Hooper with 45% of Vortex between them, and the remaining 36% divided among 20 cast and crew members. Warren Skaaren made a deal as an equal partner with Hooper and Henkel, along with a 15% share of Vortex. Skaaren received a deferred salary of $5,000 and 3% of the gross profits (MAB and Vortex combined). David Foster, producer of the 1982 horror film The Thing, arranged for a private screening for some of Bryanston Pictures' West Coast executives, and received 1.5% of Vortex's profits and a deferred fee of $500.

On August 28, 1974, Louis (Butchi) Periano of Bryanston Distribution Company offered Bozman and Skaaren a contract of $225,000 and 35% of the profits from the worldwide distribution of the film. Years later, Bozman stated, "We made a deal with the devil, , and I guess that, in a way, we got what we deserved." They signed the contract with Bryanston, and after the investors recouped their money (including interest); Skaaren's salary and monitoring fee were paid, as well as the lawyers and accountants fees, leaving only $8,100 to be divided among the 20 members of the cast and crew. Eventually, the producers sued Bryanston for failing to pay them their full percentage of the box office profits. A court judgement fined Bryanston the sum of $500,000 to be paid to the filmmakers, however, by then, the company had declared bankruptcy. Bryanston Pictures folded in 1976, when Louis Peraino was convicted on obscenity charges for his role during the production of the film Deep Throat (1972). New Line Cinema acquired the distribution rights to the film from Bryanston and gave the producers a bigger percentage of the gross profits than Bryanston had initially paid them.

Casting

Many of the cast members had few or no previous acting credits, consisting of Texans who had had previous roles in commercials, television, and stage shows, as well as actors whom Hooper knew personally. Involvement in the film propelled many cast members into the motion-picture industry. The lead role of Sally was given to the then-unknown Marilyn Burns. Burns had appeared previously on stage, and while attending the University of Texas at Austin, she joined its film commission board. Teri McMinn was a student and worked with various local theater companies, including the Dallas Theater Center. Henkel spotted her picture in the Austin American-Statesman, and called McMinn to come in for a reading. On her last call-back, he requested that she wear short shorts. Her costume proved to be the most comfortable of all the cast members' costumes, taking into consideration the Texas heat that was to last throughout the entire shoot. Icelandic-American actor Gunnar Hansen gained the role of Leatherface, and in preparation for his role, he came to envisage Leatherface as being mentally retarded and as having never learned to speak properly. Hansen visited a school for the mentally challenged and watched how the students moved and spoke in order to get a feel for his character. When commenting on the production of the film, Hansen recalled, "It was 95, 100 degrees every day during filming. They wouldn't wash my costume because they were worried that the laundry might lose it, or that it would change color. They didn't have enough money for a second costume. So I wore that 12 to 16 hours a day, seven days a week, for a month."

Filming

Filming took place in Austin, Round Rock and Bastrop, Texas, from July 15 through August 14, 1973, a period of more than four weeks. The cast and crew found the filming conditions tough. High temperatures occurred during filming, with a record high on July 26 at 97°F (36°C). The record low during the shoot was on July 31 at 83°F (28.3°C). The house used for the film was not cooled, and all ventilation was closed due to the scene being set at night time. The film was shot mainly using an Eclair NPR 16 mm camera, increased to 32 mm; with the low speed of the film requiring four times more light than modern cameras. As a result of the small budget, the crew filmed seven days a week, 12 to 16 hours a day, while having to deal with high humidity. The largest proportion of the filming took place in a remote farmhouse filled with furniture constructed from animal bones and using a latex material as upholstery to give the appearance of human skin. The crew also covered the walls of the house with splats of dried blood to make the interior look more realistic.

Art director Robert Burns drove around the countryside, collecting the bones of cattle and other animals in various stages of decomposition, which he used to litter the floors of the house. The film's special effects were simple and limited by the budget. The filmmakers discovered at least 100 cannabis plants at the back of the farmhouse: they belonged to the person renting the house at the time. The local sheriff was called to investigate, but did not arrive and the discovery of the plants was never reported. The blood depicted was sometimes real, as was the case during the filming of the scene in which Leatherface feeds "Grandpa". The crew had difficulties in getting the stage blood to come out of a tube, so instead, Burns' index finger was cut with a razor. Burns' costume was so drenched in the stage blood used during production of the film that it was virtually solid on the last day of shooting. The scene after Pam is hung on the meathook, when Leatherface first uses his chainsaw, caused some worry to actor William Vail (Kirk). Kirk was about to have his head cut off, and actor Hansen (Leatherface) told Vail not to move or he would literally be killed. Hansen then brought down the running chainsaw within 3 inches (8 cm) of Vail's face.

Release

Upon the completion of post-production, the filmmakers found it difficult to secure a distributor that was willing to market the film, due to its graphic content; however, on August 28, 1974, the Bryanston Distributing Company agreed to distribute it. The Texas Chain Saw Massacre premiered on October 1, 1974, in Austin, Texas, almost a year after the completion of filming. The film screened nationally in the United States as a Saturday afternoon matinée, and found success with a broader audience after it was falsely marketed as being a "true story". After 1976, the film was reissued to first-run theaters, every year, for eight years, with full-page ads.

Hooper reportedly hoped that the MPAA would give the complete, uncut release print a PG rating due to the minimal amount of gore presented in the film. The film was eventually released by the MPAA uncensored with an R rating. The film was ultimately banned in many countries including Australia, Brazil, Finland, West Germany, Chile, Iceland, Ireland, Norway, Singapore, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. After the initial release, including a one-year theatrical run in London, the film was banned in Britain largely on the authority of British Board of Film Classification (BBFC) Secretary James Ferman. The film saw a limited cinema release because of various city councils, including Camden Council, which granted a license to The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, which was later classified 18 by the BBFC. Censors attempted to edit the film for the purposes of a wider release in 1977 but were unsuccessful. At the time of the film's banning, the word "chainsaw" became outlawed in film titles, forcing studios to retitle their movies. One such film, Hollywood Chainsaw Hookers (1988) was retitled Hollywood Hookers, with an image of a chainsaw replacing the word. The BBFC passed the film in 1999 with no cuts. The Texas Chain Saw Massacre was broadcast a year later on Channel 4.

Australia's Censorship Board first viewed The Texas Chain Saw Massacre in June 1975, and swiftly refused to register the 83-minute print. The distributor appealed to the Review Board, which upheld the decision in August 1975. The distributor prepared a reconstructed 77-minute version, only to see it banned again in December 1975. In 1976, the Australian authorities also banned the edited version of the film. It would take five years for the film to be re-presented to the censors, and the film was banned again. Greater Union Organisation (GUO) Film Distributors were refused registration for a 2283.4 ft (83m 27s) print in July 1981. The reason given for the ban was frequent and gratuitous violence of high intensity. An 83-minute print submitted by Filmways Australia was approved for an R rating in January 1984.

Adaptations

Main article: The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (comics)Shortly after The Texas Chain Saw Massacre established itself as a success on home video in 1982, Wizard Video released a mass-market video game adaptation for the Atari 2600. In the game, the player assumes the role of the film's primary antagonist, Leatherface, and attempts to murder trespassers while avoiding obstacles such as fences and cow skulls. As one of the first horror-themed video games, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre caused controversy when it was first released, due to its violent nature, selling poorly because many game stores refused to stock it. Wizard Video's other commercial release, Halloween, based on John Carpenter's 1978 film, had a slightly better reception.

Several comic books based on The Texas Chainsaw Massacre franchise were made in 1991 by Northstar Comics, entitled Leatherface. They licensed The Texas Chainsaw Massacre rights to Avatar Press for use in new comic book stories, the first of which was published in 2005. In 2006, Avatar Press lost the license to DC Comics imprint, Wildstorm, who have published new stories based on the franchise. In June 2007, Wildstorm changed a number of horror comics, including The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, from monthly issues to specials and miniseries. The series of comics featured none of the main characters seen in the original film (Topps Comics' Jason vs. Leatherface series being an exception), with the exception of Leatherface. However, the 1991 "Leatherface" miniseries was loosely based on the third Texas Chainsaw Massacre film. Writer Mort Castle stated: "The series was very loosely based on Texas Chainsaw Massacre III. I worked from the original script by David Schow and the heavily edited theatrical release of director Jeff Burr, but had more or less free rein to write the story the way it should have been told. The first issue sold 30,000 copies."

Kirk Jarvinen drew the first issue, and Guy Burwell finished the rest of the series. The comics, not having the same restrictions from the MPAA, had much more gore than the finished film. The ending, as well as the fates of several characters, were also altered. An adaptation of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre was planned by Northstar Comics, but never came to fruition.

Home media

Since The Texas Chain Saw Massacre's premiere, the film has appeared on various home video formats, including VHS, laserdisc, CED, DVD, UMD, and Blu-ray Disc. It was first released on videotape and CED format in the 1980s by Wizard Video and Vestron Video. The film was again banned in the United Kingdom in 1984, during the moral panic surrounding video nasties. After the retirement of its secretary, Ferman, in 1999, the BBFC passed the film uncut on cinema and video, with the 18 certificate, almost 25 years after the original release. The Texas Chain Saw Massacre was originally released on DVD format in October 1998 for the United States, and, due to the controversy surrounding the film, in May 2000 for the United Kingdom. A revised DVD edition of the film was released in 2007 in Australia, after initially being released on DVD in 2001. Dark Sky Films released a region 1 two-disc edition entitled The Texas Chainsaw Massacre: Ultimate Edition, which featured several interviews, restored audio and picture quality, and other extras such as deleted scenes. Reviews for the release were largely positive, with critics praising the sound and picture quality of the restoration. A region 0 three-disc DVD edition, entitled The Texas Chain Saw Massacre: Seriously Ultimate Edition, was released on November 3, 2008. Dark Sky Films released a Blu-ray Disc version of the film on September 30, 2008. The Blu-ray was subsequently released by Second Sight Films in the United Kingdom on November 16, 2009.

Sequels

Main article: The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (franchise)The Texas Chain Saw Massacre has spawned three sequels, as well as a remake, entitled The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, produced by Michael Bay and released in 2003. The original film was first succeeded by The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 (1986), once again directed by Hooper. The sequel was considerably more graphic and violent than the original. The film was banned in Australia for 20 years, but released on DVD in a revised special edition in October 2006. The sequel was less well-received by the critics, as they felt it had moved away from the terror of the original for the sake of dark humor. Gunnar Hansen was asked to reprise his role as Leatherface in the second film, but ultimately declined.

The film spawned two more sequels; Leatherface: The Texas Chainsaw Massacre III (1990) was the next, with a budget of $2 million. Hooper did not return to direct the film due to scheduling conflicts with another film, Spontaneous Combustion, and it was instead directed by Jeff Burr. When reviewing the film, Chris Parcellin of Film Threat said, "It's really just another generic slasher flick with nothing beyond the Leatherface connection to recommend it to discerning fans." The third sequel, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre: The Next Generation, was released in 1995, starring Renée Zellweger and Matthew McConaughey. The film was a semi-remake of the original, although it was originally intended to be a complete remake of the first film. It received largely negative critical reviews; Maitland McDonagh of TV Guide's Movie Guide said that it was "tired and dated".

The remake entitled The Texas Chainsaw Massacre was released by Platinum Dunes in 2003. The film starred Jessica Biel, Eric Balfour, Andrew Bryniarski as Leatherface, and R. Lee Ermey as Sheriff Hoyt. The film received largely more positive critic reviews than the sequels, though it only managed to achieve a 36% "rotten" rating on Rotten Tomatoes, with 55 positive reviews out of 152. Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times, called it "a contemptible film: Vile, ugly and brutal." A prequel to the remake, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre: The Beginning, was released in 2006. The film was directed by Jonathan Liebesman, and produced by Michael Bay and Mike Fleiss. It had a starring cast of Matt Bomer, Jordana Brewster, and Taylor Handley, with Ermey and Bryniarski reprising their roles as Sheriff Hoyt and Leatherface, respectively. The film was panned by most critics, with a 13% "rotten" rating on Rotten Tomatoes. Mark Palermo, columnist for The Coast, said, "The focus in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre: The Beginning isn't on the confrontation of demons, moral reckoning, or terror. It's an unimaginative exercise in suffering."

Reception

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre grossed more than $30 million in the United States, making it one of the most successful independent films of all time. It was overtaken in 1978 by John Carpenter's Halloween, which grossed $47 million at the box office upon release. The film was selected for the 1975 Cannes Film Festival Directors' Fortnight, though the viewing was delayed due to a bomb scare. In 1976, the film won the Grand Prize at the Avoriaz Fantastic Film Festival in France. It was generally well-received by most critics. TV Guide called it "an intelligent, absorbing, and deeply disturbing horror film that is nearly bloodless in its depiction of violence", and Empire described it as being "the most purely horrifying horror movie ever made". Dave Kehr of The Chicago Reader said, "The picture gets to you more through its intensity than its craft, but Hooper does have a talent." Film review aggregate website Rotten Tomatoes gave the film a 90% "fresh" rating. It was named "Outstanding Film of the Year" at the 19th annual London Film Festival.

However, some reviewers disliked the film's violence and its gory special effects. The film's release in San Francisco saw moviegoers walking out of theatres in disgust. In February 1976, theatres in Ottawa, Canada, were asked by the local authority to withdraw The Texas Chain Saw Massacre due to concern about increasing levels of violence being associated by the public with the film. Linda Gross of the Los Angeles Times called it a "despicable film" and described Henkel and Hooper as being "less concerned with a plastic script". Roger Ebert wrote, "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre is as violent and gruesome and blood-soaked as the title promises ... without any apparent purpose, unless the creation of disgust and fright is a purpose ... and yet it's well-made, well-acted, and all too effective." Steve Crum of Dispatch-Tribune Newspapers criticized the film, describing it as "cultish trash that set new low standards for brutality". In his 1976 article "Fashions in Pornography" for Harper's Magazine, writer Stephen Koch described The Texas Chain Saw Massacre as "unrelenting sadistic violence as extreme and hideous as a complete lack of imagination can possibly make it". Bruce Westbrook of the Houston Chronicle called the film "a backwoods masterpiece of fear and loathing, Texas style."

After 36 years, some critics called The Texas Chain Saw Massacre one of the scariest movies ever made. Mike Emery of The Austin Chronicle said that the film was "horrifying, yet engrossing ... But the worst part about this vision is that despite its sensational aspects, it never seems too far from what could be the truth". Noted reviewer Rex Reed called it "The most terrifying motion picture I have ever seen." Fellow horror director Wes Craven has reminisced of his first viewing of the film, stating that he wondered "what kind of Mansonite crazoid" could have "conjured up such a visceral and punishing experience". Horror novelist Stephen King considers it "cataclysmic terror", and stated, "I would happily testify to its redeeming social merit in any court in the country." Variety stated, "Despite the heavy doses of gore in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, Tobe Hooper's pic is well-made for an exploiter of its type." The film has also been declared one of the few horror movies to invoke "the authentic quality of nightmare".

Legacy

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, considered one of the greatest and most controversial horror films of all time, has significantly influenced the horror genre. Ridley Scott credited the film as an inspiration for his 1979 film Alien. French director Alexandre Aja credited The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, among other films, as influencing his early career. Ben Cobb of Channel 4 called it "a triumph of style and atmosphere", and said that the film is without doubt one of the most influential horror films of all time. John Carpenter's Halloween (1978) incorporated the film's use of minimal blood and gore, and focused instead on the suspense. The film was among TIME Magazine's top 25 horror films of all time. Richard Zoglin of Time praised the film for setting "a new standard for slasher films to come". In 1990, the film was inducted into the Horror Hall of Fame, with director Hooper accepting the award. William Friedkin inducted Hooper into the 2003 Texas Film Hall of Fame. New York City's Museum of Modern Art added the film to its permanent collection, validating its claim as legitimate, unconventional art. Entertainment Weekly ranked the film #6 on their list of "The Top 50 Cult Films". Rebecca Ascher-Walsh believes that the film "paved the way for such future shock-franchises as Halloween, The Evil Dead and The Blair Witch Project". Mark Olsen of the Los Angeles Times described the film as being "cheap, grubby and out of control", and that the film "both defines and entirely supersedes the very notion of the exploitation picture". In a Total Film poll conducted in 2005, the film was selected as the greatest horror film of all time. Leatherface has gained a reputation as one of the most disturbing and notorious characters in the horror genre, and The Times listed The Texas Chain Saw Massacre as one of the 50 most controversial films of all time.

Horror filmmaker and heavy metal singer Rob Zombie sees the film as a major influence, most notably in his film House of 1000 Corpses, released in 2003. Isabel Cristina Pinedo stated, "The horror genre must keep terror and comedy in tension if it is to successfully tread the thin line that separates it from terrorism and parody... this delicate balance is struck in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre in which the decaying corpse of Grandpa not only incorporates horrific and humorous effects, but actually uses one to exacerbate the other." Scott Von Doviak of Hick Flicks called it "one of the rare horror movies to make effective use of daylight, right from the gruesome opening shot of a decaying corpse splayed across a cemetery tombstone". The book Contemporary North American Film Directors, called the film "a disquieting inspection of rural insanity, more intricate and less bloodthirsty than the title might connote”. In the book Horror Films, one critic's opinion of the film was that it was "the most affecting gore thriller of all and, in a broader view, among the most effective horror films ever made", and that "the driving force of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre is something far more horrible than aberrant sexuality: total insanity.” Christopher Null of Filmcritic.com said, "In our collective consciousness, Leatherface and his chainsaw have become as iconic as Freddy and his razors or Jason and his hockey mask." In 2008, the film ranked 199th on Empire magazine's list of The 500 Greatest Movies of All Time.

Themes and analysis

Since its release, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre has become the subject of much critical debate about the underyling themes of the film. Film critics and scholars have often interpreted the film as a classic exploitation film, where the female protagonists are often subjected to brutal, sadistic violence that borders being sexually sadistic at the hands of the primary antagonists. As is the case in many horror films, it focuses on the idea of the "final girl" trope, who is the heroine and inevitable lone survivor of the film, somehow managing to escape the horror which befalls the other characters. Sally Hardesty, the heroine of the film, possesses many of the stereotypical features of the final girl as the sole survivor, who is wounded, tortured and yet manages to escape the peril in the end, with the help of a male truck driver. Critics argue that even in films in which the male and female death ratio are roughly equal, the "lingering" images of the film will be about the violence committed towards the female characters within it. Much of the film appears - although this is largely subjective - to revolve around violence against women. Three men in the film are killed in a quick fashion, while on the other hand, one woman is slaughtered brutally by being hung on a meathook, and the surviving female is left to endure physical and mental torture before escaping her eventual death at the hands of the family of villains.

In one study conducted, a group of men were shown five films depicting various levels of violence against women, with the study finding that those who watched The Texas Chain Saw Massacre experienced symptoms of depression and anxiety at first, however, upon subsequent viewing, they found violence less offensive against women and more enjoyable. Another study conducted at the University of Missouri involved 30 male and 30 female university students and aimed to investigate gender-specific perceptions of slasher films. Of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, one male participant described the screaming, especially that of the protagonist Sally Hardy, as the "most freaky thing" in the film. The infamous meathook scene has been described as one of the most brutal on-screen deaths of a female. The scene was described as typical violence against women in the media, by portraying the woman as weak and helpless. In revealing the Sawyer family during the dinner table scene, Hooper is shown to parody a typical sitcom family, by including characters such as the cook (who is shown to be the main bread-winner), the killer Leatherface as a typical housewife, and the hitchhiker as the rebellious teenage son. Other scholars have described the film and the slasher genre as a whole, as being "sexually violent".

Various critics have also seen the film as a representation of the response of the American experience and the distinctively American struggles faced by society in the 1960s and the early to mid 1970s, subsiding a short time after the release of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. With regard to these "struggles", in particular the Watergate scandal, as well as the "delegitimation of authority in the wake of Vietnam", some critics argue that this line of thinking has been implicated in art, particularly the American horror film, and that there is an "idea of apocalypse" in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre and that the film touches upon a particular time in America when social and political unrest was present at a high level. In his analysis of the film, Robin Wood believes that Leatherface and his family are victims of oppression through industrial capitalism, their jobs as slaughter workers having been rendered obsolete by technological advances. Naomi Merritt explores the film’s representation of "cannibalistic capitalism" in relation to Georges Bataille’s theory of taboo and transgression. It is also heavily argued by some film historians and critics that the horror film, particularly since Alfred Hitchcock's Psycho (1960) and The Birds (1963) and George A. Romero's Night of the Living Dead (1968), proposes questions about the "fundamental validity of the American civilizing process".

References

- ^ Bloom, John (November 2004). Texas Monthly. Vol. 32. Emmis Communications. p. 162.

- Henkel, Kim (Writer) (2008). Kim Henkel Interview (DVD). Dark Sky Films.

{{cite AV media}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - Phillips 2005, p. 102

- ^ Template:Cite article Cite error: The named reference "AustinChronicle" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Hooper, Tobe (2008). Tobe Hooper Interview (DVD). Dark Sky Films.

{{cite AV media}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Hooper, Tobe (Director) (2008). The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (DVD). Dark Sky Films.

{{cite AV media}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - Summers, Chris (2003). "BBC Crime Case Closed – Ed Gein". BBC. Archived from the original on 2004-02-04. Retrieved 2009-10-16.

-

Bell, Rachael. "Ed Gein: The Inspiration for Buffalo Bill and Psycho". Crime Library. Retrieved 2008-11-23.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Bowen 2004, p. 17

- ^ Gregory, David (Director and Writer) (2000). Texas Chainsaw Massacre: The Shocking Truth (Documentary). Blue Underground. Retrieved 2010-06-10.

- Armstrong, Kent Byron (2003). Slasher Films: An International Filmography, 1960 through 2001. McFarland & Company. p. 316. ISBN 0786414626.

- ^ Farley, Ellen (October 1986). "The Chainsaw Massacres". Cinefantastique. Vol. 16, no. 4/5.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Gunnar, Hansen (May 1985). "A Date with Leatherface". Texas Monthly. 13 (5). Emmis Communications: 163–4, 206. ISSN 0148-7736.

- Jaworzyn 2004, p.33

- Gross, Joe (November 2003). "Movie News". SPIN. 19 (11). SPIN Media, LLC.: 52. ISSN 0886-3032.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Bozman, Ron (Production manager) (2008). The Business of Chain Saw: Interview with Ron Bozman from The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (DVD). Dark Sky Films.

{{cite AV media}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - Donahue, Suzanne Mary (1987). American film distribution: the changing marketplace. UMI Research Press. p. 235. ISBN 0835717763.

- Greenberg 1994, p.149

- ^ Jaworzyn 2004, pp. 8–33

- Briggs, Joe Bob (2003). Profoundly Disturbing: Shocking Movies that Changed History. Universe. p. 189. ISBN 0789308444.

- Jaworzyn 2004, p.30

- Jaworzyn 2004, p.63

- ^ Hansen, Gunnar. "Gunnar Hansen FAQ". gunnarhansen.com. Retrieved 2008-10-30.

- ^ Haines 2003, pp. 114–115

- Kraus, Daniel (1999). "Bone of My Bone, Flesh of My Flesh". Gadfly. Retrieved 2008-10-17.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Staff (2004-06-10). "The calm, peaceful life of Leatherface". CNN. Archived from the original on 2004-06-11. Retrieved 2009-07-26.

- ^ Triplett, Gene (2006-10-06). "First 'Chain Saw' madman remains fond of grisly role". NewsOk/The Oklahoman. Retrieved 2008-11-22.

- Freeland 2002, p. 241

- Weinstein, Farrah (2003-10-15). "'Chainsaw' Cuts Up the Screen". Fox News. Retrieved 2008-07-12.

- Template:Cite article

- Template:Cite article

- Bowen 2004, pp. 17–18

- Russo, John (1989). Making Movies: The Inside Guide to Independent Movie Production. Delacorte Press. p. 252. ISBN 0385296843.

- Muir 2002, p. 83

- Jaworzyn 2004, p.40

- Gertner, Richard (1976). International Television Almanac. Quigley Publishing Company. p. 334. OCLC 23905541.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Davis, Laura (2009-08-07). "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974)". London: The Independent. Retrieved 2009-09-21.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - Parliamentary Debates, Senate Weekly Hansard. Australian Authority. 1984. p. 776.

{{cite book}}:|first=missing|last=(help) - Chibnall 2002, p.16

- ^ Bowen 2004, p. 18

- "The Texas Chain Saw Massacre". Students' British Board of Film Classification. Retrieved 2008-06-01.

- "Texas Chainsaw Massacre Rejected by the BBFC". British Board of Film Classification. 1975-03-12. Retrieved 2009-08-15.

- Clarke, Sean (2002-03-13). "Explained: Film censorship in the UK". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2008-11-28.

- Petrie, Ruth (1997). Film and Censorship: The Index Reader. Cassell. p. 156. ISBN 0304339369.

- Morgan, Diannah (2004). Creative titling with Final Cut Pro (illustrated ed.). The Ilex Press Ltd. p. 22. ISBN 1904705154.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Quarles, Mike (2001). Down and Dirty: Hollywood's Exploitation Filmmakers and Their Movies (illustrated ed.). McFarland. p. 84. ISBN 0786411422.

- "Texas Chainsaw Massacre released uncut". BBC News Online. 1999-03-16. Retrieved 2009-05-04.

- "Screen 'video nasty' hits Channel 4". BBC News. 2000-10-16. Retrieved 2009-08-09.

- Egan, Kate (2008). Trash or Treasure?: Censorship and the Changing Meanings of the Video Nasties (illustrated ed.). Manchester University Press. p. 243. ISBN 0719072328.

- "The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (Review 1)". Office of Film and Literature Classification. 1975-06-01. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- ^ "The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (Review 2)". Office of Film and Literature Classification. 1975-12-12. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- "The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (Review 3)". Office of Film and Literature Classification. 1981-07-01. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- "The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (Review 4)". Office of Film and Literature Classification. 1984-01-01. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- ^ Shea, Tom (1983-02-28). "Horror films' themes reappear in video games". InfoWorld. 5 (9). InfoWorld Media Group. ISSN 0199-6649.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - Clark, Al (Random House). The Film Yearbook, 1984 (illustrated ed.). p. 143. ISBN 0394624882.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Montfort, Nick (2009). Racing the Beam: The Atari Video Computer System (illustrated ed.). MIT Press. p. 128.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Weiss, Brett (2007). Classic Home Video Games, 1972–1984: A Complete Reference Guide. McFarland. p. 123. ISBN 0786432268.

- Malloy, Alex G. (1992). Comics Values Annual 1992. Krause Publications. p. 442. ISBN 0870696548.

- "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre". Avatar Press. 2005. Retrieved 2008-07-08.

- Staff (2007-03-13). "Wildstorm Updates Publishing Plans for Horror/Movie Titles". Comic Book Resources. Retrieved 2008-08-21.

- "Mort Castle". Glasshouse Graphics. Retrieved 2008-06-01.

- Thompson, Don (1993). Comic-book superstars. Krause Publications. p. 40. ISBN 0873412567.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Castle, Mort (w). "Hunters in the Night" Leatherface, vol. 1, no. 4, p. 1/Introduction (1991). Northstar Comics.

- "Video Cassette: Top 25 Rentals". Billboard. 94 (7): 48. 1982. ISSN 0006-2510.

- American Film Institute; Arthur M. Sackler Foundation (1983). American film. Vol. 9. American Film Institute. p. 72.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Cherry, Bridget (2009). Horror (illustrated ed.). Taylor & Francis. p. 90. ISBN 0415456673.

- "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre rated 18 by the BBFC". British Board of Film Classification. 1999. Retrieved 2008-06-01.

- ^ "The Texas Chain Saw Massacre(1974): Reviews". Metacritic. January 1, 2000. Retrieved 2008-06-01.

- Chibnall, p.21

- Coates, Tom (2001-10-02). "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974)". BBC. Retrieved 2008-08-20.

- "The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (DVD)". Office of Film and Literature Classification. 2007-07-26. Retrieved 2009-07-07.

- ^ "Texas Chain Saw Massacre: 2 Disc Ultimate Edition". Dark Sky Films. Retrieved 2009-07-09.

- D'Arminio, Aubry (2006-10-25). "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre: Ultimate Edition (2006)". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 2009-07-09.

- Gilchrist, Todd (2006-10-05). "The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (Ultimate Edition)". IGN. Retrieved 2008-08-21.

- Staff (2006-09-19). "The Texas Chains Saw Massacre (UE)". Bloody Disgusting. Retrieved 2009-07-12.

- Van Beek, Anton (2008-11-03). "The Texas Chain Saw Massacre: 3 Disc Seriously Ultimate Edition slices through the competition". Tech Radar. Retrieved 2009-06-03.

- Dreuth, Josh (2008-05-30). "Texas Chainsaw Massacre Announced for Blu-ray". Blu-ray.com. Retrieved 2008-07-06.

- Foster, Dave (2009-10-19). "The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (UK BD) in November". The Digital Fix. Retrieved 2009-12-04.

- Goldberg, Lee (July 1986). "Tobe Hooper: Chainsaws and Invaders from Mars". Fangoria (55). Starlog Group.

- "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 – SE Film (DVD)". Office of Film and Literature Classification. 2006. Retrieved 2008-06-02.

- Ebert, Roger (1986-08-25). "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Part 2". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 2008-06-02.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - Waddell, Callum. "Gunnar Hansen: Interview". Bloody Disgusting. Retrieved 2008-09-28.

- Jaworzyn 2004, p. 188

- Parcellin, Chris (2000-10-31). "Leatherface: Texas Chainsaw Massacre III". Film Threat. Retrieved 2009-02-23.

- Maltin, Leonard (2000). Leonard Maltin's Movie and Video Guide. Signet. p. 1400. ISBN 0451201078.

- "Texas Chainsaw Massacre: The Next Generation". TVGuide.com. Retrieved 2008-06-03.

- "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 2010-04-29.

- Ebert, Roger (2003-10-17). "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 2008-06-03.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre: The Beginning". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 2010-04-29.

- Palermo, Mark (2007-03-15). "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre: The Beginning (Review)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 2009-03-22.

- "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 2008-10-13.

- Friedman 2007, p. 132

- "Halloween (1978)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 2008-12-14.

- Friedman 2007, p. 133

- "The Texas Chain Saw Massacre: Review". TVGuide.com. Retrieved 2008-07-08.

- Kehr, Dave (2007-09-19). "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre". Chicago Reader. Retrieved 2010-06-07.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 2010-04-29.

- Schneider, Steven. "Tobe Hooper". Scream Television. Archived from the original on 2002-11-21. Retrieved 2010-07-29.

- Murphy, Mary (1974-11-20). "The Perils of a 'Chainsaw' star". Los Angeles Times.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - Henry, Sarah (1976-02-13). Local film prohibition could be warning sign of anti-violence trend. Ottawa Citizen. Retrieved 2010-02-27.

{{cite book}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - Gross, Linda (1974-10-30). "'Texas Massacre' Grovels in Gore". Los Angeles Times.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - Ebert, Roger (1974-01-01). "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 2008-05-31.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - Ebert, Roger (1989). Roger Ebert's Movie Home Companion: Full-Length Reviews of Twenty Years of Movies on Video. Andrews McMeel Publishing. p. 748. ISBN 0836262409.

- Crum, Steve (2006-07-27). "Cultish trash set new low standards for brutality". Dispatch-Tribune Newspapers. Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 2009-09-29.

- Staiger, Janet (2000). Perverse Spectators: The Practices of Film Reception. NYU Press. p. 183. ISBN 081478139X.

- Westbrook, Bruce (1992-01-19). "Films love to show off tawdry side of Texas". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved 2009-05-09.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - Edmundson, Mark (1999). Nightmare on Main Street: Angels, Sadomasochism, and the Culture of Gothic. Harvard University Press. p. 22. ISBN 0674624637.

- Muir 2002 p. 17

- Bowen 2004, pp. 16–17

- Gonzales, Rob (2006). "The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (Review)". eFilmCritic. HBS Entertainment. Retrieved 2008-06-01.

- Muir 2002, p. 49

- Worland, Rick (2006). The Horror Film: An Introduction. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 1405139021.

- ^ "Texas Massacre tops horror poll". BBC News. 2005-10-09. Retrieved 2008-07-09.

- Kerekes, David; Slater, David (2000). See No Evil: Banned Films and Video Controversy (illustrated ed.). Headpress. p. 374. ISBN 1900486105.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - Gleiberman, Owen (2009-08-06). "Texas Chainsaw Massacre: The template for modern horror". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 2009-08-09.

- ^ Rockoff, Adam (2002). Going to Pieces: The Rise and Fall of the Slasher Film, 1978–1986. McFarland. p. 42. ISBN 0786412275.

- Robb, Brian (2005). Ridley Scott. Pocket Essentials. p. 37. ISBN 1904048471.

- Biodrowski, Steve (2008-09-20). "Alien Revisted: An Interview with Ridley Scott". Cinefantastique. Retrieved 2010-04-09.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - Dicker, Ron (2008-09-15). "Aja reflects on Mirrors, his life as a director". The Houston Chronicle. Retrieved 2009-05-09.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - Cobb, Ben. "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre Movie Review". Channel 4. Archived from the original on 2003-07-07. Retrieved 2008-07-09.

- "Halloween – Behind the scenes". HalloweenMovies.com. Retrieved 2008-07-09.

- "The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, 1974". TIME. 2007-10-29. Retrieved 2008-07-09.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - Zoglin, Richard (1999-08-16). "Cinema: The Predecessors: They Came from Beyond". TIME. Retrieved 2010-04-08.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - Davies, Steven Paul (2003). A-Z of cult films and film-makers (illustrated ed.). Batsford. p. 109. ISBN 0713487046.

- Jaworzyn 2004, p.126

- "The Top 50 Cult Films". Entertainment Weekly. 2003-05-16. Retrieved 2009-09-29.

- Ascher-Walsh, Rebecca (2000-11-03). "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974)". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 2008-12-26.

- Olsen, Mark (2006-08-06). "Beware, the cave man". Los Angeles Times. p. 5. Retrieved 2010-01-03.

- Graham, Jamie (2005-10-10). "Shock Horror!". Total Film. Retrieved 2009-06-17.

- "Texas Chain Saw Massacre voted best horror film". The Register. 2005-10-11. Retrieved 2008-07-12.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - Morris, Sophie (2008-10-31). "The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (18)". London: The Independent. Retrieved 2009-08-24.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - Schechter, Harold (2006). The A to Z Encyclopedia of Serial Killers (revised, illustrated ed.). Simon & Schuster. p. 232. ISBN 1416521747.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - "The frighteners". London: The Times. 2006-08-19. Retrieved 2009-08-24.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - Spencer, Megan (2003-11-25). "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre". ABC. Retrieved 2008-08-23.

- Pinedo, Isabel Cristina (1997). Recreational Terror: Women and the Pleasures of Horror Film Viewing. SUNY Press. p. 48. ISBN 0791434419.

- Von Doviak, Scott (2005). Hick Flicks: The Rise and Fall of Redneck Cinema. McFarland. p. 172. ISBN 0786419970.

- Allon, Yoram (2002). Contemporary North American Film Directors: A Wallflower Critical Guide. Wallflower Press. p. 246. ISBN 1903364523.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Weaver, James B. (1996). Horror Films: Current Research on Audience Preferences and Reactions. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. p. 36. ISBN 0805811745.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Null, Christopher (2003-11-22). "The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974)". FilmCritic.com. Retrieved 2008-07-08.

- "Empire: The Greatest Films of All Time (200–101)". Empire. Retrieved 2009-02-20.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - Wood, Robin (1985). "An Introduction to the American Horror Film" (PDF). Movies and Methods. 2. University of California Press.

- ^ Grant, Barry Keith (1996). The Dread of Difference: Gender and the Horror Film (illustrated ed.). University of Texas Press. p. 82. ISBN 0292727941.

- Prince, Stephen (2000). Screening Violence (illustrated ed.). Continuum. p. 146. ISBN 0485300958.

- ^ Bogart, Leo (2000). Commercial Culture: The Media System and the Public Interest (2, illustrated ed.). Transaction Publishers. p. 349. ISBN 0765806053.

- Linz, Daniel (September 1984). "The Effects of Multiple Exposures to Filmed Violence Against Women". Journal of Communication. 34 (3): 130–147. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.1984.tb02180.x.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Nolan, Justin M. (2000). "Fear and Loathing at the Cineplex: Gender Differences in Descriptions and Perceptions of Slasher Films". Sex Roles. 42 (1 & 2). Plenum Publishing Corporation: 39. ISSN 0360-0025.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Mackey, Mary (1977). "Women and Violence in Film". Jump Cut. Retrieved 2009-11-15.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - Newman, Kim. "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre". Film Reference. Retrieved 2009-11-15.

- Weaver, James B. III (Summer 1991). "Are Slasher Horror Films Sexually Violent?". Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media. 35 (3). Routledge: 385–392. ISSN 1550-6878.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - Grant 2004, p.301

- ^ Grant 2004, p. 300

- Grant 2004, p.308

- Merritt, Naomi (2010). "Cannibalistic Capitalism and other American Delicacies: A Bataillean Taste of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre". Film-Philosophy. 14 (1). Open Humanities Press. ISSN 1466-4615. Retrieved 2010-04-15.

Bibliography

- Bowen, John W. (2004). "Return Of The Power Tool Killer". Rue Morgue Magazine (42). Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Marrs Media, Inc.: 16–22. ISSN 1481-1103.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Chibnall, Steve (2002). British Horror Cinema. Routledge. ISBN 0415230047.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Dika, Vera (2003). Recycled Culture in Contemporary Art and Film: The Uses of Nostalgia. Britain: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521016312.

- Friedman, Lester D. (2007). American Cinema of the 1970s: Themes and Variations. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 0813540232.

- Freeland, Cynthia A. (2002). The Naked and the Undead: Evil and the Appeal of Horror. Westview Press. ISBN 0813365635.

- Grant, Barry Keith (2004). "The Idea of Apocalypse in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre". Planks of Reason: Essays on the Horror Film. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0810850133.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Greenberg, Harvey Roy (1994). Screen Memories: Hollywood Cinema on the Psychoanalytic Couch. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0231072872.

- Haines, Richard W. (2003). The Moviegoing Experience, 1968–2001. McFarland. ISBN 0786413611.

- Hand, Stephen (2004). The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. Games Workshop. ISBN 1844160602.

- Jaworzyn, Stefan (2004). The Texas Chain Saw Massacre Companion. Titan Books. ISBN 1840236604.

- Merritt, Naomi (2010). "Cannibalistic Capitalism and other American Delicacies: A Bataillean Taste of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre". Film-Philosophy. 14 (1). Open Humanities Press. ISSN 1466-4615.

- Muir, John Kenneth (2002). Horror Films of the 1970s. McFarland & Company. p. 332. ISBN 0786412496.

- Muir, John Kenneth (2002). Eaten Alive at a Chainsaw Massacre: The Films of Tobe Hooper. McFarland & Company. ISBN 0786412828.

- Phillips, Kendall R. (2005). "The Exorcist (1973) and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974)". Projected Fears: Horror Films and American Culture. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0275983536.

- Williams, Tony (1977). "American Cinema in the '70s: The Texas Chainsaw Massacre". Movie (25): 12–16.

{{cite journal}}: Text "United Kingdom" ignored (help)

External links

- The Texas Chain Saw Massacre at IMDb

- Template:Amg movie

- The Texas Chain Saw Massacre at Metacritic

- The Texas Chain Saw Massacre at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Texas Chainsaw Massacre: A Visit to the Film Locations

- The Junction House – The restaurant now operating in the original house from the film

| The Texas Chainsaw Massacre | |

|---|---|

| Films | |

| Video games |

|

| Characters | |

| Related | |

| Films directed by Tobe Hooper | |

|---|---|

|