| Revision as of 14:35, 5 February 2006 view source80.3.13.35 (talk) →External links← Previous edit | Revision as of 14:38, 5 February 2006 view source El C (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Administrators183,806 editsm Reverted edits by 80.3.13.35 (talk) to last version by JllNext edit → | ||

| Line 133: | Line 133: | ||

| * | * | ||

| * | * | ||

| However isn't it dangerous | |||

| ==References== | ==References== | ||

Revision as of 14:38, 5 February 2006

Template:Mtnbox start norange Template:Mtnbox coor dm Template:Mtnbox volcano Template:Mtnbox climb Template:Mtnbox finish

- This article is about the volcano in Italy. For other uses, see Vesuvius (disambiguation).

Mount Vesuvius (Italian: Monte Vesuvio) (also Somma-Vesuvius or Somma-Vesuvio) is a volcano east of Naples, Italy, located at 40°49′N 14°26′E / 40.817°N 14.433°E / 40.817; 14.433. It is the only volcano on the European mainland to have erupted within the last hundred years, although it is not currently erupting. The only other two such volcanoes in Italy are located on islands.

Vesuvius is situated on the coast of the Bay of Naples, about nine kilometres (six miles) to the east of the city and a short distance inland from the shore. It forms a conspicuous feature in the beautiful landscape presented by that bay, when viewed from the sea, with the city in the foreground. The mountain is notorious for its destruction of the Roman cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum in AD 79. It has erupted many times since and is today regarded as one of the most dangerous volcanoes in the world because of the population of three million people now living close to it coupled with its tendency towards explosive eruptions.

Origin of the name

Mount Vesuvius was regarded by the Greeks and Romans as being sacred to the hero and demigod Hercules/Heracles, and the town of Herculaneum, built at its base, was named after him. The mountain is also named after Hercules in a less direct manner: he was the son of the god Zeus and Alcmene of Thebes. Zeus was also known as Ves (Template:Polytonic) in his aspect as the god of rains and dews. Hercules was thus alternatively known as Vesouvios (Template:Polytonic), "Son of Ves." This name was corrupted into "Vesuvius."

According to other sources, Vesuvius came from the Oscan word fesf which means "smoke."

There is a theory that the name "Vesuvius" is derived from the Indo-European root ves- = "hearth".

Physical aspects

Vesuvius is a distinctive "humpbacked" mountain, consisting of a large cone (Gran Cono) partially encircled by the steep rim of a summit caldera caused by the collapse of an earlier, and originally much higher structure called Monte Somma. For this reason, the volcano is also called Somma-Vesuvius or Somma-Vesuvio.

The caldera started forming during an eruption around 17000 (or 18,300) years ago , and was enlarged by later paroxysmal eruptions ending in the one of 79 AD. This structure has given its name to the term somma volcano, which describes any volcano with a summit caldera surrounding a newer cone .

The height of the main cone has been constantly modified by eruptions but presently stands at 1,281m (4,202ft). Monte Somma is 1,149m (3,770ft) high, separated from the main cone by the valley of Atrio di Cavallo, which is some 3 miles (5 km) long. The slopes of the mountain are scarred by lava flows but are heavily vegetated, with scrub at higher altitudes and vineyards lower down. It is still regarded as an active volcano although its activity currently is limited to little more than steam from vents at the bottom of the crater. Vesuvius is a composite volcano at the convergent boundary where the African Plate is being subducted beneath the Eurasian Plate. Its lava is composed of viscous andesite. Layers of lava, scoriae, ashes, and pumice make up the mountain.

Eruptions

Vesuvius has erupted repeatedly in recorded history, most famously in 79 and subsequently in 472, 512, in 1631, six times in the 18th century, eight times in the 19th century (notably in 1872), and in 1906, 1929, and 1944. There has been no eruption since 1944. The eruptions vary greatly in severity but are characterised by explosive outbursts of the kind dubbed Plinian after the Roman writer who observed the AD 79 eruption. On occasion, the eruptions have been so large that the whole of southern Europe has been blanketed by ashes; in 472 and 1631, Vesuvian ashes fell on Constantinople (now known as Istanbul), over 1,000 miles away.

Before AD 79

The mountain started forming 25,000 years ago. Although the area has been subject to volcanic activity for at least 400,000 years, the lowest layer of eruption material from the Somma mountain lies on top of the 34,000 year-old Campanian Ignimbrite produced by the Campi Flegrei complex, and was the product of the Cordola plinian eruption 25,000 years ago.

It was then built up by a series of lava flows, with some smaller explosive eruptions interspersed between them. However, the style of eruption changed around 19,000 years ago to a sequence of large explosive plinian eruptions, of which the 79 AD one was the last. The eruptions are named after the tephra deposits produced by them:

- The Basal Pumice (Pomici di Base) eruption, 18,300 years ago, VEI 6, was probably the most violent of these eruptions and saw the original formation of the Somma caldera.

- The Green Pumice (Pomici verdoline) eruption, 16,000 years ago, VEI 5, followed a period in which several lava-producing eruptions had taken place.

- The Mercato eruption (also known as Pomici Gemelle or Ottaviano), 8,000 years ago, VEI 6, followed a smaller explosive eruption around 11,000 years ago (called the Lagno Amendolare eruption).

- The Avellino eruption (Pomici di Avellino), 3,800 years ago, VEI 6, followed two smaller explosive eruptions around 5,000 years ago. The Avellino eruption vent was apparently 2 km west of the current crater, and the eruption destroyed several Bronze Age settlements. The remarkably well-preserved remains of one were discovered in May 2001 near Nola by Italian archaeologists, with huts, pots, livestock and even the footprints of animals and people. The residents had hastily abandoned the village, leaving it to be buried under pumice and ash in much the same way that Pompeii was later preserved.

The volcano then entered a stage of more frequent, but less violent, eruptions until the most recent plinian eruption which destroyed Pompeii.

The last of these may have been in 217 BC. There were earthquakes in Italy during that year and the sun was reported as being dimmed by a haze or dry fog. Plutarch wrote of the sky being on fire near Naples and Silius Italicus mentioned in his epic poem Punica that Vesuvius had thundered and produced flames worthy of Mount Etna in that year, although both authors were writing around 250 years later. Greenland ice core samples of around that period show relatively high acidity, which is assumed to have been caused by atmospheric hydrogen sulfide.

The mountain was then quiet for hundreds of years and was described by Roman writers as having been covered with gardens and vineyards, except at the top which was craggy. Within a large circle of nearly perpendicular cliffs was a flat space large enough for the encampment of the army of the rebel gladiator Spartacus in 73 BC. This area was doubtless a crater. The mountain may have had only one summit at that time, judging by a wall painting, "Bacchus and Vesuvius", found in a Pompeiian house, the House of the Centenary (Casa del Centenario).

Several surviving works written over the 200 years preceeding the 79 AD eruption describe the mountain as having had a volcanic nature, although Pliny the Elder did not depict the mountain in this way in his Naturalis Historia:

- The Greek historian Strabo (ca 63 BC-24 AD) described the mountain in Book V, Chapter 4 of his Geographica as having a predominantly flat, barren summit covered with sooty, ash-coloured rocks and suggested that it might once have had "craters of fire". He also perceptively suggested that the fertility of the surrounding slopes may be due to volcanic activity, as at Mount Etna.

- In Book II of De Architectura, the architect Vitruvius (ca 80-70 BC -?) reported that fires had once existed abundantly below the mountain and that it had spouted fire onto the surrounding fields. He went on to describe Pompeiian Pumice as having been burnt from another species of stone.

- Diodorus Siculus (ca 90 BC – ca 30 BC), another Greek writer, wrote in Book IV of his Bibliotheca Historica that the Campanian plain was called fiery (Phlegrean) because of the mountain, Vesuvius, which had spouted flame like Etna and showed signs of the fire that had burnt in ancient history.

The area was then, as now, densely populated with villages, towns and small cities like Pompeii, and its slopes were covered in vineyards and farms.

Eruption of 79

The devastating eruption of 79 was preceded by powerful earthquakes in 62, which caused widespread destruction around the Bay of Naples. Earth tremors were commonplace in the region. The Romans, however, were entirely ignorant of the link between earthquakes and vulcanism, and grew used to them; the writer Pliny the Younger wrote that they "were not particularly alarming because they are frequent in Campania."

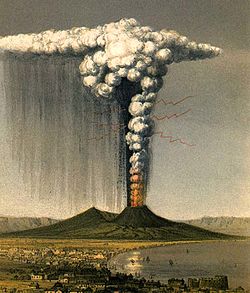

This complacency proved fatal for many on August 24, 79, when the mountain erupted spectacularly. It was recorded for posterity by the younger Pliny, who observed the eruption and recorded it in two famous letters to the historian Tacitus. He saw an extraordinarily dense and rapidly-rising cloud appearing above the mountain:

- I cannot give you a more exact description of its figure, than by resembling it to that of a pine tree; for it shot up to a great height in the form of a tall trunk, which spread out at the top into a sort of branches. It appeared sometimes bright, and sometimes dark and spotted, as it was either more or less impregnated with earth and cinders.

What he had seen was a column of ash, now estimated to have been more than 20 miles (32 km) tall.

His uncle Pliny the Elder was that day in command of the Roman fleet at Misenum, on the far side of the bay, and decided to see for himself what was going on. Taking a ship across the bay, the elder Pliny encountered thick showers of hot cinders, lumps of pumice and pieces of rock, blocking his approach to the port of Retina. He went instead to Stabiae where he landed and took shelter with Pomponianus, a friend, in the town's bath house.

Pliny and his party saw flames coming from several parts of the mountain (probably a sign of pyroclastic flows and surges, which would later destroy Pompeii and Herculaneum). After resting for a short time in the bath house, the party had to evacuate it due to the torrential rain of tephra (ash, cinders, and/or rock) filling the courtyard leading to the building. Violent earthquakes shook the town, adding to the danger. Pliny, Pomponianus and their companions made their way back towards the beach with pillows tied on their heads to protect them from the rockfall. By this time, there was so much ash in the air that the party could barely see through the murk and needed torches and lanterns to find their way. They made it to the beach but found the water too violently disturbed from the continuous earthquakes for them to escape safely by sea.

Pliny the Elder collapsed and died, and in the first letter to Tacitus his nephew suggested that this was due to the inhalation of poisonous, sulphurous gases. However, Stabiae was 16 km from the vent (roughly where the modern town of Castellammare di Stabia is) and his companions were apparently unaffected by the fumes, and so it is more likely that the corpulant Pliny died through a different cause, such as a stroke or heart attack. His body was found two days later with no visible physical injuries.

The eruption is thought to have lasted about 19 hours, in which time the volcano released about 1 cubic mile (4 cubic kilometres) of ash and rock over a wide area to the south and south-east of the crater. Pompeii, Herculaneum and other towns around Vesuvius were destroyed, with about 3m (10ft) of tephra falling on Pompeii. Around 2,000 people are believed to have died in the town, the vast majority as the result of suffocation by volcanic ashes and gases. Herculaneum, which was much closer to the crater, was saved from tephra falls by the wind direction, but was buried under 23m (75ft) of ash deposited by pyroclastic surges. Pompeii and Herculaneum were never rebuilt, although surviving townspeople and probably looters did undertake extensive salvage work after the destructions. The towns' locations were eventually forgotten until their accidental rediscovery in the 18th century. Vesuvius itself underwent major changes - its slopes were denuded of vegetation and its summit had changed considerably due to the force of the eruption.

Later eruptions

Since the eruption of 79, Vesuvius has erupted around three dozen times. It erupted again in 203, during the lifetime of the historian Cassius Dio. In 472, it ejected such a volume of ash that ashfalls were reported as far away as Constantinople. The eruptions of 512 were so severe that those inhabiting the slopes of Vesuvius were granted exemption from taxes by Theodoric the Great, the Gothic king of Italy. Further eruptions were recorded in 787, 968, 991, 999, 1007 and 1036 with the first recorded lava flows. The volcano became quiescent at the end of the 13th century and in the following years it again became covered with gardens and vineyards as of old. Even the inside of the crater was filled with shrubbery.

Vesuvius entered a new and particularly destructive phase in December 1631, when a major eruption buried many villages under lava flows, killing around 3,000 people. Torrents of boiling water were also ejected, adding to the devastation. Activity thereafter became almost continuous, with relatively severe eruptions occurring in 1660, 1682, 1694, 1698, 1707, 1737, 1760, 1767, 1779, 1794, 1822, 1834, 1839, 1850, 1855, 1861, 1868, 1872, 1906, and 1944. The eruption of 1906 was particularly destructive, killing over 100 people and ejecting the most lava ever recorded from a Vesuvian eruption. Its last eruption came in March 1944, destroying the villages of San Sebastiano al Vesuvio, Massa di Somma and part of San Giorgio a Cremano as World War II continued to rage in Italy.

The volcano has been quiescent ever since. Over the past few centuries, the quiet stages have varied from 18 months to 7½ years, making the current lull in activity the longest in nearly 500 years. While Vesuvius is not thought likely to erupt in the immediate future, the danger posed by future eruptions is seen as very high in the light of the volcano's tendency towards sudden extremely violent explosions and the very dense human population on and around the mountain.

The future

Large plinian eruptions which emit magma in quantities of about 1 km³ or more, the most recent of which overwhelmed Pompeii, have happened after periods of inactivity of a few thousand years. Sub-plinian eruptions producing about 0.1 km³, such as those of 472 and 1631, have been more frequent with a few hundred years between them. Following the 1631 eruption until 1944 every few years saw a comparatively small eruption which emitted 0.001-0.01 km³ of magma. It seems that for Vesuvius the amount of magma expelled in an eruption increases very roughly linearly with the interval since the previous one, and at a rate of around 0.001 km³ for each year. This gives an extremely approximate figure of 0.06 km³ for an eruption after 60 years of inactivity.

Magma sitting in an underground chamber for many years will start to see higher melting point constituents such as olivine crystallising out. The effect is to increase the concentration of dissolved gases (mostly steam and carbon dioxide) in the remaining liquid magma, making the subsequent eruption more violent. As gas-rich magma approaches the surface during an eruption, the huge drop in pressure caused by the reduction in weight of the overlaying rock (which drops to zero at the surface) causes the gases to come out of solution, the volume of gas increasing explosively from nothing to perhaps many times that of the accompanying magma. Additionally, the removal of the lower melting point material will raise the concentration of felsic components such as silicates potentially making the magma more viscous, adding to the explosive nature of the eruption.

The emergency plan for an eruption therefore assumes that the worst case will be an eruption of similar size and type to the 1631 one (which was VEI 4). In this scenario the slopes of the mountain, extending out to about 7 kilometres (4.3 miles) from the vent, may be exposed to pyroclastic flows sweeping down them, whilst much of the surrounding area could suffer from tephra falls. Because of prevailing winds, towns to the south and east of the volcano are most at risk from this, and it is assumed that tephra accumulation exceeding 100 Kg/m² – at which point people are at risk from collapsing roofs – may extend out as far as Avellino to the east or Salerno to the south east. Towards Naples, to the north west, this tephra fall hazard is assumed to barely extend past the slopes of the volcano . The specific areas actually affected by the ash cloud will depend upon the particular circumstances surrounding the eruption .

The plan assumes between 20 days and two weeks notice of an eruption and foresees the evacuation of 600,000 people, almost entirely comprising all those living in the zona rossa ("red zone"), i.e. at greatest risk from pyroclastic flows. The evacuation, by trains, ferries, cars and buses is planned to take about seven days, and the evacuees will mostly be sent to other parts of the country rather than to safe areas in the local Campania region, and may have to stay away for several months. However the dilemma that would face those implementing the plan is when to start this massive evacuation, since if it is left too late then many people could be killed, whilst if it is started too early then the precursors of the eruption may turn out to have been a false alarm. In 1984, 40,000 people were evacuated from the Campi Flegrei area, another volcanic complex near Naples, but no eruption occurred .

Ongoing efforts are being made to reduce the population living in the red zone, by demolishing illegally constructed buildings, establishing a national park around the upper flanks of the volcano to prevent the erection of further buildings and by offering financial incentives to people for moving away. The underlying goal is to reduce the time needed to evacuate the area, over the next 20 or 30 years, to two or three days.

The volcano is closely monitored by the Osservatorio Vesuvio in Naples with extensive networks of seismic and gravimetric stations, a combination of a GPS-based geodic array and satellite-based synthetic aperture radar to measure ground movement, and by local surveys and chemical analyses of gases emitted from fumaroles. All of this is intended to track magma rising underneath the volcano. So far, no magma has been detected within 10 km of the surface, and so the volcano is at worst only in the very early stages of preparing for an eruption.

Vesuvius Today

The area around Vesuvius was offically declared a national park on 5 June 1995. The summit of Vesuvius is open to visitors and there is a small network of paths around the mountain that are maintained by the park authorities on weekends.

External links

- Account of 1785 eruption by Hester Thrale.

- Stromboli Online - Vesuvius & Campi Flegrei

- Bronze age settlement destroyed 3,500 years ago

- Wall painting of Vesuvius found in Pompeii

- Translation of Pliny the Elder's Natural History

- Translation of Book V, Chapter 4 of Strabo's Geographica

- Translation of Book II of Vitruvius' De Architectura

- Greek, Carthaginian, and Roman Agricultural Writers (includes Pliny the Elder)

- Derivation of the name "Plinian" (UCSB Volcano Information Center)

- Translation of Pliny the Younger's letters

- ERUPT Project - Vesuvius

- Herculaneum: Destruction and Re-discovery

- Live Mount Vesuvius Webcams: from Casalnuovo, from Sorrento

- Official Vesuvius National Park website (in Italian)

- Vesuvius National Park brochure (Adobe PDF)

- Vesuvius National Park

- Summary of the emergency plan for the Vesuvius area (in Italian)

- National emergency plan for the Vesuvius area (in Italian)

- US Today article on Vesuvius emergency preparation

- Disaster preparedness page for the US Naval Support Actitivy Naples

- Early Warning of Volcanic eruptions and Earthquakes in the neapolitan area, Campania Region, South Italy

- Guardian Newspaper article - "In the shadow of the volcano"

- Guardian Newspaper article "Italy ready to pay to clear slopes of volcano"

- Tango Diva article - "Mount Vesuvius, the sleeping giant"

- Explore Italian Volcanoes, at Dipartimento di Fisica "E. Amaldi" Universita' Roma Tre, Italy

- Image of Vesuvius at Volcano World

- Top volcanoes worldwide (i.e. Famous and recent eruptions)

- Global volcanism program entry on Somma-Vesuvius

- Definition of a somma volcano

- Geotimes article - "Vesuvius’ next eruption"

- Vesuvius Observatory

References

- . ISBN 0-691-05081-3.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help); Unknown parameter|Author=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Publisher=ignored (|publisher=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Title=ignored (|title=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Year=ignored (|year=suggested) (help) - . ISBN 1-903544-04-1.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help); Unknown parameter|Author=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Publisher=ignored (|publisher=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Title=ignored (|title=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Year=ignored (|year=suggested) (help)