| Revision as of 09:13, 29 December 2010 edit93.191.77.99 (talk) →External links← Previous edit | Revision as of 11:13, 11 March 2011 edit undoMaterialscientist (talk | contribs)Edit filter managers, Autopatrolled, Checkusers, Administrators1,994,339 edits expandNext edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{refimprove|date=November 2010}} | |||

| {{Other uses|Pavlovsk (disambiguation)}} | {{Other uses|Pavlovsk (disambiguation)}} | ||

| {{Infobox Russian inhabited locality | {{Infobox Russian inhabited locality | ||

| Line 36: | Line 35: | ||

| |inhabloc_cat=Town | |inhabloc_cat=Town | ||

| |date=October 2009}} | |date=October 2009}} | ||

| '''Pavlovsk''' ({{lang-ru|Па́вловск}}) is a ] |

'''Pavlovsk''' ({{lang-ru|Па́вловск}}) is a ]n ] under the jurisdiction of ]. It is located {{convert|30|km|sp=us}} south from St. Petersburg and about 4 km southeast from ]. The town developed around the ], a major residence of the Russian imperial family. Between 1918 and 1944 its official name was Slutsk, after the revolutionary Vera Slutskaya, and then was changed back to Pavlovsk. Pavlovsk is part of the ] ] '']''. | ||

| == Geology == | |||

| The town developed around the ], one of the most splendid ] of the Russian imperial family. It is of the ] '']''. | |||

| The town is located on the Neva Lowland, on the left bank of the river ], in the valley of the ]. The landscape is quite varied and contains hills, ridges and terraces intermixed with valleys, plains, forests and farmland. Numerous springs give rise to streams and feed ponds. In the ] era, 300–400 million years ago, the area was covered by a sea. Sediments of that time form a layer thicker than 200 meters on top of the ] consisting of ], ] and ]. The modern topography was shaped by the ] retreat some 12,000 years ago which created the ]. About 4,000 years ago the sea receded and formed the valley of the Neva River which has not changed much over the last 2,500 years.<ref name="Geografiya Leningrada">Darinskii, pp. 12–18</ref> | |||

| == |

== Climate == | ||

| The climate of Pavlovsk is ] and wet, it is transitional between ] and ]. The length of the day varies from 5 hours and 51 minutes in the winter ] to 18 hours and 50 minutes in the summer ]. Summer is short and moderately warm, whereas winter is long and uneven, with frequent thaws. Air temperatures above 0 °C prevail from early April to mid-November. The coldest month is February. Winds mostly blow southward and frequently change air mass above the city. Summer is dominated by westerly and northwesterly winds, and the wind direction changes to westerly and southwesterly in winter. The cloudiest months are November, December and January, and the least cloudy are May, June and July. There are at least 240 sunny days per year. Between 25 May and 16 July ] are observed when the sun only briefly goes over the horizon and the day lasts nearly 19 hours. The area is mostly fed by surface and ground waters.<ref name="Geografiya Leningrada2">Darinskii, pp. 21–29</ref><ref name="Atlas Lo">{{cite book|part = Weather Map|title = Atlas of the Leningrad Region|location = Moscow|Publisher = GUGK USSR CM|year = 1967|pages = 20–24}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Weather box | |||

| The town's history started in 1777 when ] granted some 362 ]s (977 acres; 395 ha) of land along the ] to her son ] upon the birth of his first child. The name Pavlovsk derives from Paul's name in Russian, ''Pavel''. | |||

| |location= Pavlovsk | |||

| | Jan mean C=-6.5 | Jan precipitation mm=40 | |||

| | Feb mean C=-6.0 | Feb precipitation mm=31 | |||

| | Mar mean C=-1.4 | Mar precipitation mm=35 | |||

| | Apr mean C=4.4 | Apr precipitation mm=33 | |||

| | May mean C=10.9 | May precipitation mm=38 | |||

| | Jun mean C=15.8 | Jun precipitation mm=64 | |||

| | Jul mean C=17.7 | Jul precipitation mm=78 | |||

| | Aug mean C=16.4 | Aug precipitation mm=77 | |||

| | Sep mean C=11.0 | Sep precipitation mm=67 | |||

| | Oct mean C=5.6 | Oct precipitation mm=65 | |||

| | Nov mean C=-0.1 | Nov precipitation mm=56 | |||

| | Dec mean C=-3.9 | Dec precipitation mm=49 | |||

| | year mean C=5.2 | year precipitation mm=633 | |||

| | Jan low C=-7.9 | Jan high C=-2.3 | |||

| | Feb low C=-7.7 | Feb high C=-1.4 | |||

| | Mar low C=-2.9 | Mar high C=4.1 | |||

| | Apr low C=1.6 | Apr high C=9.2 | |||

| | May low C=7.1 | May high C=16.1 | |||

| | Jun low C=11.9 | Jun high C=20.5 | |||

| | Jul low C=14.0 | Jul high C=22.2 | |||

| | Aug low C=13.0 | Aug high C=20.6 | |||

| | Sep low C=8.0 | Sep high C=14.6 | |||

| | Oct low C=3.7 | Oct high C=8.5 | |||

| | Nov low C=-2.1 | Nov high C=1.8 | |||

| | Dec low C=-5.5 | Dec high C=-0.7 | |||

| | year low C=2.8 | year high C=9.4 | |||

| | Jan record high C=8.6 | Jan record low C=-35.9 | |||

| | Feb record high C=10.2 | Feb record low C=-35.2 | |||

| | Mar record high C=14.9 | Mar record low C=-29.9 | |||

| | Apr record high C=25.3 | Apr record low C=-21.8 | |||

| | May record high C=30.9 | May record low C=-6.6 | |||

| | Jun record high C=34.6 | Jun record low C=0.1 | |||

| | Jul record high C=35.3 | Jul record low C=4.9 | |||

| | Aug record high C=33.5 | Aug record low C=1.3 | |||

| | Sep record high C=30.4 | Sep record low C=-3.1 | |||

| | Oct record high C=21.0 | Oct record low C=-12.9 | |||

| | Nov record high C=12.3 | Nov record low C=-22.2 | |||

| | Dec record high C=10.9 | Dec record low C=-34.4 | |||

| | year record high C=35.3 | year record low C=-35.9 | |||

| |source 1=<ref name="Geografiya Leningrada2" /><ref>{{cite web|url = http://pogoda.ru.net/climate/26063.htm|title = Weather & Climate|publisher = pogoda.ru.net|accessdate = 2010-02-28}}</ref> | |||

| }} | |||

| == Soil, vegetation and wildlife == | |||

| In 1780, the fashionable ] architect ] was made responsible for construction activities in Pavlovsk. His ] design for the Grand Palace was approved by Paul two years later. Around the palace a huge ] was laid out, with numerous temples, colonnades, bridges, and statues. | |||

| ] in Pavlovsk Park]] | |||

| ] | |||

| Prior to the founding of the town the area was covered by ]s (mostly pine and ]) with an admixture of broad-leaved trees and ]s. The soils were mostly ], combined with ] and ]. Intensive economic activities changed the original forest landscape to agricultural land with small groves of ], ], ] and ]. In the 18–19th centuries, a large park area of almost 600 hectares (Pavlovsk and Arensky parks) has been created in and around the city.<ref name="Geografiya Leningrada3">Darinskii, pp. 45–49</ref> | |||

| Owing to the parks and environment-friendly policies, the Pavlovsk area has relatively low level of pollution.<ref name="Demografiya">{{cite web|url = http://www.gov.spb.ru/gov/admin/terr/reg_pavlovsk/Total|title = Пушкинский район в 2008 году, основные итоги экономического и социального развития (Pushkin region in 2008, main results of the economic and social development)|publisher = Administration of St. Petersburg|accessdate = 2010-02-28}}</ref> In 1978–1983 the Pavlovsk Park contained more than 360,000 trees of 54 species: 16 species of spruce, pine, ] and fir, two species of ], two species of ], two of ], oaks, elm, ], ], ], ], 88 shrub species, of which the dominant were yellow acacia, ] and ]. In 1978, there were 71 species of birds belonging to 28 families and 9 orders. Mammals include squirrels, hares, ]s, ]s, moles, shrews, hedgehogs, red voles and ]s. In winter, the parks are sometimes visited by fox, wild boar and moose. Amphibians and reptiles are mostly frogs, toads and lizards. There are 87 species of insects belonging to 46 families.<ref>http://www.viktur.ru/excursion/saint-petersburg/pavlovsk-196-285.html#19473</ref><ref name="Atlas Lo2">{{cite book|chapter = Охотничье-промысловые звери, птицы и рыбы (Animals, poultry and fish)|title = Atlas of the Leningrad Region|location = Moscow|Publisher = GUGK USSR CM|year = 1967|pages = 36–37}}</ref> | |||

| When Paul ascended the throne as Paul I in 1796, the settlement near the palace was large enough to be incorporated as a city. After Paul's death the palace was proclaimed a residence of his widow, ]. Then it passed to the Konstantinovichi branch of the ]. | |||

| As most rivers of Saint Petersburg, the Slavyanka River is polluted. Water analysis performed by Greenpeace in 2008 reveals contamination levels exceeding the permissible norms by tens or hundreds times, with such chemicals as oil, lead, ], ], ] and others. Most pollution originates from household waste deposited by 16 companies.<ref>В петербургской воде обнаружены запредельные концентрации токсичных веществ // REGIONS.RU 25.06.2008</ref><ref>Колпино: заводская, но чистая окраина. "metro-Санкт-Петербург" № 151(1055) (29 August 2006), p. 3</ref> | |||

| ==Later history== | |||

| ==Population== | |||

| Prior to the revolution, Pavlovsk was a favourite summer retreat for well-to-do inhabitants of the Russian capital. The life of Pavlovsk's ''dachniki'' was described by ] in his novel ]. | |||

| According to the 2002 census, 14,960 people lived in Pavlovsk of which 44.4% were males and 55.6% females.<ref name="PopCensus">Федеральная служба государственной статистики (Federal State Statistics Service) (2004-05-21). (in Russian). Всероссийская перепись населения 2002 года (All-Russia Population Census of 2002). Federal State Statistics Service. . Retrieved 2009-08-19.</ref> | |||

| {| Class = "wikitable" | |||

| To facilitate transportation, the first ] in Russia was opened between St Petersburg and Pavlovsk on October 10, 1837. The ] was used as a sort of concert hall, with ], ], and ] among many celebrities that performed there. The impressive '] Pavilion' is also used to attract customers to the railway line. Strauss' finer pieces resulted around the time he held his concerts there. The pavilion's fame eventually caused the word "Vokzal" to enter the Russian language with the meaning "substantial railway station building". | |||

| |+Population of Pavlovsk<ref name="MG">{{cite web|url = http://www.mojgorod.ru/gor_spb/pavlovsk/index.html|title = Pushkin|publisher = The People's Encyclopedia of Russian cities and regions "My City"| accessdate = 2010-02-28}}</ref> | |||

| !Year | |||

| !1780 | |||

| !1794 | |||

| !1897 | |||

| !1959 | |||

| !1970 | |||

| !1979 | |||

| !1989 | |||

| !1991 | |||

| !1998 | |||

| !2002 | |||

| |- | |||

| !Population | |||

| |54<ref name=j>, Journal «Адреса»</ref> | |||

| |300<ref name="Георги">{{cite book|author = ]|title = Описание российско-императорского столичного города САНКТ-ПЕТЕРБУРГ и достопримечательностей в окрестностях оного, с планом (Description of Russian imperial capital of St. Petersburg and attractions in the vicinity thereof, with a plan)|location = St. Petersburg.|publisher = Лига|year = 1996|pages = 496–504}}</ref> | |||

| |4,900 | |||

| |16,600 | |||

| |21,000<ref name=bse>, ] on-line (in Russian)</ref> | |||

| |25,200 | |||

| |25,500 | |||

| |25,400<ref name=brit>, Encyclopedia Britannica on-line</ref> | |||

| |24,800 | |||

| |14,960 | |||

| |} | |||

| ==History== | |||

| ===Fortress=== | |||

| ] | |||

| A wooden fortress was built by Russians on the place of Pavlovsk and was known from at least 13th century as part of an ]. The fortress and the entire region were later captured by the Swedes. On 13 August 1702, the Russian army led by ] and ] met Swedes at the ] and pushed them to the fortress. For several days, the Swedish Army was reinforcing their positions but were expelled upon a surprise frontal attack.<ref name="Георги"/> | |||

| ], an avid fan of military, had long dreamed of building a stone fortress on the ruins of the Swedish forts. After he became an Emperor, in 1796, he hired the Italian architect ] and raised money for the project. By 1798 Brenna raised a Gothic ], Bip fortress, which fascinated Paul so much that he listed it on the Army register of real fortresses. After the death of Catherine, Paul and Brenna expanded the Pavlovsk estate with real military barracks, officers' quarters and a hospital.<ref name=H94>Hayden 2005, p. 94</ref><ref name="L50">Lanceray, pp. 51–52</ref><ref name=bip/> | |||

| ===Imperial residence=== | |||

| {{seealso|Pavlovsk Palace}} | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] liked the nature in Pavlovsk area and frequently visited it for hunting trips. In December 1777, she assigned to her son, Paul I, 362 ]s (977 acres; 395 ha) of land along the ], together with forests, arable land and two small villages with peasants. This was a present to Paul and his wife ] on the occasion of the birth of their first son, the future Emperor ]. This date is considered the founding date of the Pavlovskoye village (the name Pavlovsk derives from Paul's name in Russian, ''Pavel''). Catherine commissioned the Scottish architect ], who had previously done much work for her in the nearby Tsarskoye Selo, to design a palace and a park in Pavlovskoye.<ref>{{cite book|author=Kuchumov , A. M.|title= Павловск. Путеводитель по дворцу-музею и парку (Pavlovsk. Palace and Park Guidebook). |place=St. Petersburg|publisher= Лениздат|year=1970}}</ref><ref name=brit/><ref name=bse/> | |||

| Between 1782 and 1786<ref name=brit/> Cameron built the original palace core that survives to date, the Temple of Friendship, Private Gardens, Aviary, Apollo Colonnade and the Lime Avenue. He also planned the original landscape including the huge ] with numerous temples, colonnades, bridges, and statues. The Temple of Friendship was the first building in Pavlovsk, followed by the main palace.<ref>Hayden, p. 120</ref> However, Cameron's Pavlovsk was far from Paul's vision of what an imperial residence should be: it lacked moats, forts and all other military assortments so dear to Paul; "Cameron created a markedly private world for the Grand Duke. The palace could have belonged to anyone... not to the tsar of Russia in waiting."<ref name=S281>Shvidkovsky, p. 281</ref> Constrained financially, Paul and Maria closely watched Cameron's progress and regularly curbed his far-reaching, expensive plans. Between 1786 and 1789 Cameron's duties in Pavlovsk passed to Brenna.<ref>Shvidkovsky, 284</ref><ref>Hayden, p. 120</ref> | |||

| Paul personally hired Brenna, then employed by ], in 1782, and used him in 1783–1785 to visualize his architectural fantasies.<ref name=L85>Lanceray, p. 85</ref> Brenna left Cameron's palace core intact, extending it with side wings; although he remodeled the interiors, they bear traces of Cameron's style to date. However, Maria's private suite and the ] displayed in public halls are attributed to Brenna alone.<ref name=L47>Lanceray, pp. 47–49</ref> | |||

| In 1794, the population of Pavlovskoye counted 300 people, mostly peasants and palace servants. There was a stone church, a free public school for peasants and three hospitals: regular, military and for invalids. Later, an agriculture school and the first in Russia school for the deaf were established in Pavlovskoye.<ref name=m/> Between 1807 and 1810, the school for the deaf was located in the Bip fortress. Later, a military regimen was stationed and practiced there.<ref name=bip/><ref name="Георги">{{cite book|author = ]|title = Описание российско-императорского столичного города САНКТ-ПЕТЕРБУРГ и достопримечательностей в окрестностях оного, с планом (Description of Russian imperial capital of St. Petersburg and attractions in the vicinity thereof, with a plan)|location = St. Petersburg.|publisher = Лига|year = 1996|pages = 496–504}}</ref> Theatrical performances were regularly staged first in the palace and since 1794 in the theater built nearby by Brenna.<ref name=m/> | |||

| Pavel favored as his residence ] to Pavlovskoye, and therefore, since 1788 the latter was managed by his wife who had contributed most to its well-being.<ref>{{cite book|author=Schwartz V|title=Пригороды Ленинграда (Suburbs of Leningrad)|place=St. Petersburg – Moscow|publisher= Искусство|year=1967}}</ref> Maria Feodorovna enjoyed animal husbandry (she used to milk cows herself) and thus built a large farm at the edge of the park and a wooden pavilion for studies. She was also a skilled artist, a member of Berlin Academy of Arts, and her numerous handicrafts still remain in the palace. A large collection of books was accumulated in the palace by her efforts.<ref name=m/> In 1796, the village received a status of a ] and renamed to Pavlovsk.<ref name=brit/><ref name=bse/> | |||

| ===After Paul I=== | |||

| ] | |||

| ] in Pavlovsk on the occasion of 25th anniversary of the Tsarskoye Selo Railways]] | |||

| After Paul's death in 1801 the palace was proclaimed a residence of his widow, Maria Feodorovna. During that time, it was frequently visited by famous poets and novelists including ], ]<ref name=bip/> and ]. ] was a regular reader for Maria Feodorovna and the teacher of Russian language and literature for ], the wife of ] who inherited Pavlovsk after the death of Maria Feodorovna in 1828. Michael Pavlovich spent his childhood in Pavlovsk, and then cared much about the city. Being a military person, he mostly improved well-being of the military corps staged near Pavlovsk and built barracks, riding stables, forge and workshops. But he also improved the roads of Pavlovsk, donated significant amounts to the church and established an orphanage and a school for middle-class children.<ref name=m/> | |||

| In the 19th century, Pavlovsk became a favorite summer retreat for well-to-do inhabitants of the Russian capital. The life of Pavlovsk's ''dachniki'' was described by ], who frequently visited the town, in his novel ].<ref name=m/> To facilitate transportation, the first ] in Russia, the ], was built around 1836. The first test runs were performed between Pavlovsk and Tsarskoye Selo using carriages horse-drawn over the rails. Regular trains powered by ] began operating between Pavlovsk and St. Petersburg from May 1838. Aiming to promote the railways, the train terminal of Pavlovsk was built in 1836–1838 as an entertaining center. It then regularly hosted evening festivities, and ] (1856), ], ] and ] were among the celebrities who performed there.<ref name=r3>, Промтехдепо</ref><ref name=r4>http://family-history.ru/material/history/spb/spb_33.html</ref><ref name=r5>Golyanov A. L. and Zakrevskaya G. P. , Museum of Russian Railways, St. Petersburg (in Russian)</ref> The station was called '] Pavilion', and its fame eventually caused the modified from Vauxhall word "Vokzal" to enter the Russian language, with the meaning "substantial railway station building".<ref>, ] on-line (in Russian)</ref> | |||

| Michael Pavlovich died in 1849 leaving no heir, and thus Pavlovsk became property of a son of Nicholas I, ]. Konstantin Nikolayevich established in 1872 an art gallery and a museum in the palace and opened them for public access. He also promoted construction in 1876 of a laboratory dedicated to meteorology and study of magnetic fields on the outskirts of the park. Pavlovsk became a popular residence and by 1874 had 323 summer cottages. The celebrities living here included ], ] and ]. <ref name=m/> | |||

| ===Birthplace of Russian Scouting=== | |||

| On 30 April 1909 a young officer, Colonel ], organized the first Russian ] troop ''Beaver'' ({{lang|ru|Бобр}}, ''Bobr'') in Pavlovsk. In 1910, ], the founder of the ], visited ] in ]. They had a pleasant conversation, and a scouting badge was issued to ]. In 1914, Pantyukhov established a ] called ''Russian Scout'' ({{lang|ru|Русский Скаут}}, ''Russkiy Skaut''). The first Russian Scout campfire was lit in the woods of Pavlovsk Park. After the ] of 1917, and during the ] from 1918 to 1920, most of the scoutmasters and many scouts fought in the ranks of the ] and interventionists against the ]; the scout movement was therefore regarded negatively in the Soviet Russia and disbanded after the war.<ref name=Pravoveriye> {{ru icon}}</ref><ref>{{cite book | |||

| | last = Kroonenberg | |||

| | first = Piet J. | |||

| | authorlink = Piet J. Kroonenberg | |||

| | title = The Undaunted- The Survival and Revival of Scouting in Central and Eastern Europe | |||

| | publisher = Oriole International Publications | |||

| | location = Geneva | |||

| | date = 1998 | |||

| | pages =75–103 | |||

| | isbn = 2880520037 }}</ref> | |||

| ===Soviet time=== | |||

| ] | |||

| After the ] of 1917, the Pavlovsk palace and park were nationalized and converted to a public-access museum. In a general motion to replace Tsar's name, the town was renamed to Slutsk, after revolutionary Vera Slutskaya who died nearby in 1917. Later it was often mentioned in the documents under a double name Slutsk (Pavlovsk), and eventually regained the old name in 1944.<ref name=j/> | |||

| Pavlovsk suffered much from the German occupation during World War II (16 September 1941 – 24 January 1944) – the entire water system of the park and about 70,000 trees were destroyed, the palace was severely damaged by the fire of January 1944, and about 40% of exhibitions were stolen or destroyed (the rest was evacuated to Siberia before arrival of the Germans). The old train station was burned down and rebuilt in the 1950s by A. E. Levinson. The town was liberated as a result of the ].<ref name="Prigorody Leningrada">{{cite book|author = Schwarz W.|title = The suburbs of Leningrad|location = St. Petersburg, Moscow|publisher = Искусство|year = 1967|pages = 123–189}}</ref><ref name=m2>, State Museum of Pavlovsk</ref> Restoration works started in 1944 and were completed by 1973.<ref name=brit/><ref name=bse/> Nowadays about 1.5 million tourists visit Pavlovsk annually.<ref name=j/> | |||

| In 1954, Pavlovsk was transferred under the jurisdiction of St. Petersburg.<ref name=j/> In 1989, it was included into the ] list of ]s as part of the ].<ref>http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/540-007</ref> In 2003, historical names were returned to dozens of streets of Pavlovsk which were renamed during the Soviet time.<ref>, (Decree of 6 February 2006 No. 117 on names of the municipal objects) Government of St. Petersburg (in Russian)</ref> | |||

| ==Coat of arms== | |||

| The first coat of arms of Pavlovsk was approved by ] in 1801. It features a black ] with a white ] on its chest and the ] hanging on a chain under it. On top of the cross there is a red shield with a ] combining Russian italic letters П and М standing for Emperor Paul and Empress Maria. The eagle has gilded beaks and paws. It holds a ] and ] in the paws; it is crowned with two golden crowns with two more crowns near its heads. The whole composition is placed on a golden shield. There was a proposal of an alternative coat during the Soviet times, but it was not approved.<ref>, Russian Centre of Vexillology and Heraldry</ref> The updated coat of arms was adopted on 19 September 2007. It has the same composition but with slightly simplified shapes and colors.<ref> (Coat of arms of Pavlovsk) geraldika.ru</ref> The modern flag of Pavlovsk was adopted on the same day. It contains the coat image on a yellow rectangle with the length to width ratio of 3:2.<ref> (Flag of Pavlovsk) geraldika.ru</ref> | |||

| ==Layout and architecture of the town== | |||

| ] | |||

| The center of the town is Pavlovsk Palace consisting of main body and wings connected with it by galleries. In front of the palace, welcoming the visitors stands bronze monument of Paul. It is an 1872 copy of the original cast by Giovanni Vitali. North to it lies Pavlovsk Park which covers 2/3 of the town area. With the area of about 600 hectares, the park is one of the largest in Russia and Europe.<ref>Санкт-Петербург: Энциклопедия. — СПб.: Бизнес-Пресса, 2006.</ref> Seven parts are distinguished within the park. There are numerous pavilions, and one part contains a collection of bronze statues. The Bip fortress, a favorite of young Paul I, was burned down during World War II and only its walls remain; the fortress is being restored.<ref name=bip>, НП"Петербургский Строительный Клуб"</ref> | |||

| Before 1917 there was no separation between the imperial residence and the town, and both belonged to one owner. Along the southern and western borders of the park run the main street, which is now called Sadovaya Street, and its previous names were Fyodorovskaya (before 1783), Tsarskoselskaya (1783–1919) and Revolyutsii (Soviet time). On the west, this street leads to the train terminal and then to ]. The western border of the town is the railway St. Petersburg – ].<ref>Топонимическая энциклопедия Санкт-Петербурга. — СПб.: Информационно-издательское агентство ЛИК, 2002.</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| The Pavlovsk palace is probably the best preserved of Russian imperial residences outside the capital. The sumptuous neoclassical and ] interior of the palace was faithfully restored after the great fire in 1803. The damage sustained by the palace during the German occupation in 1941–1943, though considerable, was not so devastating as in the case of ] and ]. | |||

| There are several churches near the palace, the oldest being Maria Magdalena Church and Church of Peter and Paul (built in 1799 by Brenna). The former was raised in 1781–1784 by ] and is the first classical stone building in Pavlovsk. More prominent however is the Cathedral of St. Nicholas in honor of Paul I, an active Orthodox church built in 1900–1904 by Alexander von Hohen in the ] style. | |||

| ==Notable residents== | |||

| ==Birthplace of Russian Scouting== | |||

| *] – ] and owner of Pavlovsk between 1796 and 1801.<ref name=m>, State Museum of Pavlovsk</ref> | |||

| On April 30, 1909 a young officer, Colonel ], organized the first Russian ] troop ''Beaver'' ({{lang|ru|Бобр}}, ''Bobr'') in Pavlovsk. In 1910, ] visited ] in ] and they had a very pleasant conversation, as the ] remembered it. In 1914, Pantyukhov established a ] called ''Russian Scout'' ({{lang|ru|Русский Скаут}}, ''Russkiy Skaut''). The first Russian Scout campfire was lit in the woods of Pavlovsk Park in Tsarskoye Selo. A Russian Scout song exists to remember this event. | |||

| *] (1858–1915) – grandson of ], a poet and playwright, President of the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences, owner of Pavlovsk between 1882 and 1915. Died in Pavlovsk.<ref name=m/> | |||

| <center><gallery> | |||

| *] (1827–1882) – son of ], admiral of the Russian fleet and reformer of the ], owner of Pavlovsk between 1849 and 1882. Died in Pavlovsk.<ref name=m/> | |||

| Image:Pavlovsk 1001.jpg|Railway station Pawlowsk | |||

| *] (1798–1849) – son of ] and ]. Owner of Pavlovsk between 1828 and 1849.<ref name=m/> | |||

| Image:Pavlovsk palace.jpg|Palace in Pavlovsk | |||

| *] (1886–1918) – son of ] and owner of Pavlovsk between 1915 and 1918. Born in Pavlovsk.<ref name=m/> | |||

| Image:Apollo's colonnade.JPG|Pavlovsk park with the columns of Apollo in the background | |||

| *] – daughter of Emperor ], sister of ] and wife of ]. She was an art collector and President of the ] of ]. Born in Pavlovsk.<ref name=m/> | |||

| Image:PavlovskPalace temple.jpg|Pavlovsk park: Friendship temple | |||

| *] (1759–1828) – the second wife of Tsar ] and mother of Tsar ] and Tsar ]. Owner of Pavlovsk between 1788 and 1828. Died in Pavlovsk.<ref name=m/> | |||

| </gallery></center> | |||

| *] (1851–1926) – ] of King ] and briefly in 1920, ] of Greece. The great-grandmother of ], the paternal grandmother of ], and the great-grandmother of ]. Born in Pavlovsk.<ref name=m/> | |||

| *] (1774–1845) – writer and statesman, General and Minister of Finances, died in Pavlovsk. | |||

| *] (1875–1946) – Russian graphic artist, painter, sculptor, mosaicist, and illustrator, born in Pavlovsk. | |||

| *] (1804–1877) – literature critic and historian, academician of the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences. Died in Pavlovsk. | |||

| *] (1897–1978) – a painter who lived in Pavlovsk between 1912 and 1927. | |||

| ==References== | ==References== | ||

| {{Reflist}} | {{Reflist|30em}} | ||

| ==Bibliography== | |||

| *{{cite book|author = Darinskii AV|title = География Ленинграда (Geography of Leningrad)|location = St. Petersburg|publisher = Lenizdat|year = 1982}} | |||

| *{{cite book | author=Hayden, Peter | url=http://books.google.com/books?id=nRaWLp7FGroC | title=Russian Parks and Gardens | publisher=Frances Lincoln | year=2005 | isbn=0711224307}} | |||

| * {{ cite book | author=] | year=2006 | title=Vincenzo Brenna (Винченцо Бренна) | language=Russian | id=ISBN 5-901841-34-4 | publisher=Saint Petersburg: Kolo }} | |||

| *{{cite book | author=Shvidkovsky, Dmitry | title=Russian architecture and the West | publisher=Yale University Press | year=2007 |isbn=0300109121| url=http://books.google.com/books?id=LQy9TJ2yOQEC}} | |||

| ==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| Line 75: | Line 215: | ||

| * | * | ||

| * | * | ||

| * | * | ||

| * | * | ||

| * | * | ||

| * | * | ||

| * | * | ||

| * | * | ||

| *{{cite news |first=Olivier |last=Bernier |title=Russia's Reborn Splendor |url=http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?sec=travel&res=950DE2DE1730F932A35753C1A96F948260 |work=New York Times |date=1 October 1989 |accessdate=2006-12-15 |

*{{cite news |first=Olivier |last=Bernier |title=Russia's Reborn Splendor |url=http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?sec=travel&res=950DE2DE1730F932A35753C1A96F948260 |work=New York Times |date=1 October 1989 |accessdate=2006-12-15}} | ||

| {{Imperial palaces in Russia}} | {{Imperial palaces in Russia}} | ||

| Line 106: | Line 246: | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| Line 112: | Line 253: | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

Revision as of 11:13, 11 March 2011

For other uses, see Pavlovsk (disambiguation). Town in Saint Petersburg, Russia| Pavlovsk Павловск | |

|---|---|

| Town | |

Entrance to the Park with Pavilion "Three Graces" Entrance to the Park with Pavilion "Three Graces" | |

Flag Flag Coat of arms Coat of arms | |

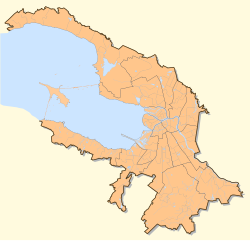

| Location of Pavlovsk | |

| |

| Coordinates: 59°41′N 30°26′E / 59.683°N 30.433°E / 59.683; 30.433 | |

| Country | Russia |

| Federal subject | Saint Petersburg |

| Founded | 1777 |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (MSK |

| OKTMO ID | 40387000 |

Pavlovsk (Template:Lang-ru) is a Russian town under the jurisdiction of Saint Petersburg. It is located 30 kilometers (19 mi) south from St. Petersburg and about 4 km southeast from Pushkin. The town developed around the Pavlovsk Palace, a major residence of the Russian imperial family. Between 1918 and 1944 its official name was Slutsk, after the revolutionary Vera Slutskaya, and then was changed back to Pavlovsk. Pavlovsk is part of the UNESCO World Heritage Site Saint Petersburg and Related Groups of Monuments.

Geology

The town is located on the Neva Lowland, on the left bank of the river Neva, in the valley of the Slavyanka River. The landscape is quite varied and contains hills, ridges and terraces intermixed with valleys, plains, forests and farmland. Numerous springs give rise to streams and feed ponds. In the Paleozoic era, 300–400 million years ago, the area was covered by a sea. Sediments of that time form a layer thicker than 200 meters on top of the Baltic Shield consisting of granite, gneiss and diabase. The modern topography was shaped by the glacier retreat some 12,000 years ago which created the Littorina Sea. About 4,000 years ago the sea receded and formed the valley of the Neva River which has not changed much over the last 2,500 years.

Climate

The climate of Pavlovsk is temperate and wet, it is transitional between oceanic and continental. The length of the day varies from 5 hours and 51 minutes in the winter solstice to 18 hours and 50 minutes in the summer solstice. Summer is short and moderately warm, whereas winter is long and uneven, with frequent thaws. Air temperatures above 0 °C prevail from early April to mid-November. The coldest month is February. Winds mostly blow southward and frequently change air mass above the city. Summer is dominated by westerly and northwesterly winds, and the wind direction changes to westerly and southwesterly in winter. The cloudiest months are November, December and January, and the least cloudy are May, June and July. There are at least 240 sunny days per year. Between 25 May and 16 July white nights are observed when the sun only briefly goes over the horizon and the day lasts nearly 19 hours. The area is mostly fed by surface and ground waters.

| Climate data for Pavlovsk | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F | 47.5 | 50.4 | 58.8 | 77.5 | 87.6 | 94.3 | 95.5 | 92.3 | 86.7 | 69.8 | 54.1 | 51.6 | 95.5 |

| Mean daily maximum °F | 27.9 | 29.5 | 39.4 | 48.6 | 61.0 | 68.9 | 72.0 | 69.1 | 58.3 | 47.3 | 35.2 | 30.7 | 48.9 |

| Daily mean °F | 20.3 | 21.2 | 29.5 | 39.9 | 51.6 | 60.4 | 63.9 | 61.5 | 51.8 | 42.1 | 31.8 | 25.0 | 41.4 |

| Mean daily minimum °F | 17.8 | 18.1 | 26.8 | 34.9 | 44.8 | 53.4 | 57.2 | 55.4 | 46.4 | 38.7 | 28.2 | 22.1 | 37.0 |

| Record low °F | −32.6 | −31.4 | −21.8 | −7.2 | 20.1 | 32.2 | 40.8 | 34.3 | 26.4 | 8.8 | −8.0 | −29.9 | −32.6 |

| Average precipitation inches | 1.6 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.5 | 2.5 | 3.1 | 3.0 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 2.2 | 1.9 | 24.9 |

| Record high °C | 8.6 | 10.2 | 14.9 | 25.3 | 30.9 | 34.6 | 35.3 | 33.5 | 30.4 | 21.0 | 12.3 | 10.9 | 35.3 |

| Mean daily maximum °C | −2.3 | −1.4 | 4.1 | 9.2 | 16.1 | 20.5 | 22.2 | 20.6 | 14.6 | 8.5 | 1.8 | −0.7 | 9.4 |

| Daily mean °C | −6.5 | −6.0 | −1.4 | 4.4 | 10.9 | 15.8 | 17.7 | 16.4 | 11.0 | 5.6 | −0.1 | −3.9 | 5.2 |

| Mean daily minimum °C | −7.9 | −7.7 | −2.9 | 1.6 | 7.1 | 11.9 | 14.0 | 13.0 | 8.0 | 3.7 | −2.1 | −5.5 | 2.8 |

| Record low °C | −35.9 | −35.2 | −29.9 | −21.8 | −6.6 | 0.1 | 4.9 | 1.3 | −3.1 | −12.9 | −22.2 | −34.4 | −35.9 |

| Average precipitation mm | 40 | 31 | 35 | 33 | 38 | 64 | 78 | 77 | 67 | 65 | 56 | 49 | 633 |

| Source: | |||||||||||||

Soil, vegetation and wildlife

Prior to the founding of the town the area was covered by temperate coniferous forests (mostly pine and fir) with an admixture of broad-leaved trees and fens. The soils were mostly podzol, combined with peat and gleysols. Intensive economic activities changed the original forest landscape to agricultural land with small groves of aspen, birch, alder and willow. In the 18–19th centuries, a large park area of almost 600 hectares (Pavlovsk and Arensky parks) has been created in and around the city.

Owing to the parks and environment-friendly policies, the Pavlovsk area has relatively low level of pollution. In 1978–1983 the Pavlovsk Park contained more than 360,000 trees of 54 species: 16 species of spruce, pine, larch and fir, two species of birch, two species of willow, two of basswood, oaks, elm, alder, aspen, European Rowan, Bird Cherry, 88 shrub species, of which the dominant were yellow acacia, meadowsweet and dogwoods. In 1978, there were 71 species of birds belonging to 28 families and 9 orders. Mammals include squirrels, hares, weasels, stoats, moles, shrews, hedgehogs, red voles and muskrats. In winter, the parks are sometimes visited by fox, wild boar and moose. Amphibians and reptiles are mostly frogs, toads and lizards. There are 87 species of insects belonging to 46 families.

As most rivers of Saint Petersburg, the Slavyanka River is polluted. Water analysis performed by Greenpeace in 2008 reveals contamination levels exceeding the permissible norms by tens or hundreds times, with such chemicals as oil, lead, acetone, mercury, chloroform and others. Most pollution originates from household waste deposited by 16 companies.

Population

According to the 2002 census, 14,960 people lived in Pavlovsk of which 44.4% were males and 55.6% females.

| Year | 1780 | 1794 | 1897 | 1959 | 1970 | 1979 | 1989 | 1991 | 1998 | 2002 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 54 | 300 | 4,900 | 16,600 | 21,000 | 25,200 | 25,500 | 25,400 | 24,800 | 14,960 |

History

Fortress

A wooden fortress was built by Russians on the place of Pavlovsk and was known from at least 13th century as part of an Administrative division of Novgorod Land. The fortress and the entire region were later captured by the Swedes. On 13 August 1702, the Russian army led by Peter the Great and Fyodor Apraksin met Swedes at the Izhora River and pushed them to the fortress. For several days, the Swedish Army was reinforcing their positions but were expelled upon a surprise frontal attack.

Paul I, an avid fan of military, had long dreamed of building a stone fortress on the ruins of the Swedish forts. After he became an Emperor, in 1796, he hired the Italian architect Vincenzo Brenna and raised money for the project. By 1798 Brenna raised a Gothic folly, Bip fortress, which fascinated Paul so much that he listed it on the Army register of real fortresses. After the death of Catherine, Paul and Brenna expanded the Pavlovsk estate with real military barracks, officers' quarters and a hospital.

Imperial residence

See also: Pavlovsk Palace

Catherine II liked the nature in Pavlovsk area and frequently visited it for hunting trips. In December 1777, she assigned to her son, Paul I, 362 desyatinas (977 acres; 395 ha) of land along the Slavyanka River, together with forests, arable land and two small villages with peasants. This was a present to Paul and his wife Maria Feodorovna on the occasion of the birth of their first son, the future Emperor Alexander I of Russia. This date is considered the founding date of the Pavlovskoye village (the name Pavlovsk derives from Paul's name in Russian, Pavel). Catherine commissioned the Scottish architect Charles Cameron, who had previously done much work for her in the nearby Tsarskoye Selo, to design a palace and a park in Pavlovskoye.

Between 1782 and 1786 Cameron built the original palace core that survives to date, the Temple of Friendship, Private Gardens, Aviary, Apollo Colonnade and the Lime Avenue. He also planned the original landscape including the huge English park with numerous temples, colonnades, bridges, and statues. The Temple of Friendship was the first building in Pavlovsk, followed by the main palace. However, Cameron's Pavlovsk was far from Paul's vision of what an imperial residence should be: it lacked moats, forts and all other military assortments so dear to Paul; "Cameron created a markedly private world for the Grand Duke. The palace could have belonged to anyone... not to the tsar of Russia in waiting." Constrained financially, Paul and Maria closely watched Cameron's progress and regularly curbed his far-reaching, expensive plans. Between 1786 and 1789 Cameron's duties in Pavlovsk passed to Brenna.

Paul personally hired Brenna, then employed by Stanisław Kostka Potocki, in 1782, and used him in 1783–1785 to visualize his architectural fantasies. Brenna left Cameron's palace core intact, extending it with side wings; although he remodeled the interiors, they bear traces of Cameron's style to date. However, Maria's private suite and the militaria displayed in public halls are attributed to Brenna alone.

In 1794, the population of Pavlovskoye counted 300 people, mostly peasants and palace servants. There was a stone church, a free public school for peasants and three hospitals: regular, military and for invalids. Later, an agriculture school and the first in Russia school for the deaf were established in Pavlovskoye. Between 1807 and 1810, the school for the deaf was located in the Bip fortress. Later, a military regimen was stationed and practiced there. Theatrical performances were regularly staged first in the palace and since 1794 in the theater built nearby by Brenna.

Pavel favored as his residence Gatchina to Pavlovskoye, and therefore, since 1788 the latter was managed by his wife who had contributed most to its well-being. Maria Feodorovna enjoyed animal husbandry (she used to milk cows herself) and thus built a large farm at the edge of the park and a wooden pavilion for studies. She was also a skilled artist, a member of Berlin Academy of Arts, and her numerous handicrafts still remain in the palace. A large collection of books was accumulated in the palace by her efforts. In 1796, the village received a status of a town and renamed to Pavlovsk.

After Paul I

After Paul's death in 1801 the palace was proclaimed a residence of his widow, Maria Feodorovna. During that time, it was frequently visited by famous poets and novelists including Sergey Glinka, Nikolay Karamzin and Ivan Krylov. Vasily Zhukovsky was a regular reader for Maria Feodorovna and the teacher of Russian language and literature for Princess Charlotte of Württemberg, the wife of Grand Duke Michael Pavlovich of Russia who inherited Pavlovsk after the death of Maria Feodorovna in 1828. Michael Pavlovich spent his childhood in Pavlovsk, and then cared much about the city. Being a military person, he mostly improved well-being of the military corps staged near Pavlovsk and built barracks, riding stables, forge and workshops. But he also improved the roads of Pavlovsk, donated significant amounts to the church and established an orphanage and a school for middle-class children.

In the 19th century, Pavlovsk became a favorite summer retreat for well-to-do inhabitants of the Russian capital. The life of Pavlovsk's dachniki was described by Dostoyevsky, who frequently visited the town, in his novel The Idiot. To facilitate transportation, the first railway in Russia, the Tsarskoe Selo Railways, was built around 1836. The first test runs were performed between Pavlovsk and Tsarskoye Selo using carriages horse-drawn over the rails. Regular trains powered by steam locomotives began operating between Pavlovsk and St. Petersburg from May 1838. Aiming to promote the railways, the train terminal of Pavlovsk was built in 1836–1838 as an entertaining center. It then regularly hosted evening festivities, and Johann Strauss II (1856), Franz Liszt, Robert Schumann and Feodor Chaliapin were among the celebrities who performed there. The station was called 'Vauxhall Pavilion', and its fame eventually caused the modified from Vauxhall word "Vokzal" to enter the Russian language, with the meaning "substantial railway station building".

Michael Pavlovich died in 1849 leaving no heir, and thus Pavlovsk became property of a son of Nicholas I, Grand Duke Konstantin Nikolayevich of Russia. Konstantin Nikolayevich established in 1872 an art gallery and a museum in the palace and opened them for public access. He also promoted construction in 1876 of a laboratory dedicated to meteorology and study of magnetic fields on the outskirts of the park. Pavlovsk became a popular residence and by 1874 had 323 summer cottages. The celebrities living here included Alexander Brullov, Peter Clodt von Jürgensburg and Vladimir Sollogub.

Birthplace of Russian Scouting

On 30 April 1909 a young officer, Colonel Oleg Pantyukhov, organized the first Russian Scout troop Beaver (Бобр, Bobr) in Pavlovsk. In 1910, General Baden-Powell, the founder of the Scout Movement, visited Nicholas II in Tsarskoye Selo. They had a pleasant conversation, and a scouting badge was issued to Tsarevich Alexei. In 1914, Pantyukhov established a society called Russian Scout (Русский Скаут, Russkiy Skaut). The first Russian Scout campfire was lit in the woods of Pavlovsk Park. After the October Revolution of 1917, and during the Russian Civil War from 1918 to 1920, most of the scoutmasters and many scouts fought in the ranks of the White Army and interventionists against the Red Army; the scout movement was therefore regarded negatively in the Soviet Russia and disbanded after the war.

Soviet time

After the October Revolution of 1917, the Pavlovsk palace and park were nationalized and converted to a public-access museum. In a general motion to replace Tsar's name, the town was renamed to Slutsk, after revolutionary Vera Slutskaya who died nearby in 1917. Later it was often mentioned in the documents under a double name Slutsk (Pavlovsk), and eventually regained the old name in 1944.

Pavlovsk suffered much from the German occupation during World War II (16 September 1941 – 24 January 1944) – the entire water system of the park and about 70,000 trees were destroyed, the palace was severely damaged by the fire of January 1944, and about 40% of exhibitions were stolen or destroyed (the rest was evacuated to Siberia before arrival of the Germans). The old train station was burned down and rebuilt in the 1950s by A. E. Levinson. The town was liberated as a result of the Krasnoye Selo–Ropsha Offensive. Restoration works started in 1944 and were completed by 1973. Nowadays about 1.5 million tourists visit Pavlovsk annually.

In 1954, Pavlovsk was transferred under the jurisdiction of St. Petersburg. In 1989, it was included into the UNESCO list of World Heritage Sites as part of the Saint Petersburg and Related Groups of Monuments. In 2003, historical names were returned to dozens of streets of Pavlovsk which were renamed during the Soviet time.

Coat of arms

The first coat of arms of Pavlovsk was approved by Alexander I in 1801. It features a black double-headed eagle with a white Maltese cross on its chest and the Order of St. Andrew hanging on a chain under it. On top of the cross there is a red shield with a monogram combining Russian italic letters П and М standing for Emperor Paul and Empress Maria. The eagle has gilded beaks and paws. It holds a ceremonial mace and globus cruciger in the paws; it is crowned with two golden crowns with two more crowns near its heads. The whole composition is placed on a golden shield. There was a proposal of an alternative coat during the Soviet times, but it was not approved. The updated coat of arms was adopted on 19 September 2007. It has the same composition but with slightly simplified shapes and colors. The modern flag of Pavlovsk was adopted on the same day. It contains the coat image on a yellow rectangle with the length to width ratio of 3:2.

Layout and architecture of the town

The center of the town is Pavlovsk Palace consisting of main body and wings connected with it by galleries. In front of the palace, welcoming the visitors stands bronze monument of Paul. It is an 1872 copy of the original cast by Giovanni Vitali. North to it lies Pavlovsk Park which covers 2/3 of the town area. With the area of about 600 hectares, the park is one of the largest in Russia and Europe. Seven parts are distinguished within the park. There are numerous pavilions, and one part contains a collection of bronze statues. The Bip fortress, a favorite of young Paul I, was burned down during World War II and only its walls remain; the fortress is being restored.

Before 1917 there was no separation between the imperial residence and the town, and both belonged to one owner. Along the southern and western borders of the park run the main street, which is now called Sadovaya Street, and its previous names were Fyodorovskaya (before 1783), Tsarskoselskaya (1783–1919) and Revolyutsii (Soviet time). On the west, this street leads to the train terminal and then to Pushkin. The western border of the town is the railway St. Petersburg – Vitebsk.

There are several churches near the palace, the oldest being Maria Magdalena Church and Church of Peter and Paul (built in 1799 by Brenna). The former was raised in 1781–1784 by Giacomo Quarenghi and is the first classical stone building in Pavlovsk. More prominent however is the Cathedral of St. Nicholas in honor of Paul I, an active Orthodox church built in 1900–1904 by Alexander von Hohen in the Russian Revival style.

Notable residents

- Paul I of Russia – Emperor of Russia and owner of Pavlovsk between 1796 and 1801.

- Grand Duke Constantine Constantinovich of Russia (1858–1915) – grandson of Nicholas I of Russia, a poet and playwright, President of the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences, owner of Pavlovsk between 1882 and 1915. Died in Pavlovsk.

- Grand Duke Konstantin Nikolayevich of Russia (1827–1882) – son of Nicholas I of Russia, admiral of the Russian fleet and reformer of the Russian Navy, owner of Pavlovsk between 1849 and 1882. Died in Pavlovsk.

- Grand Duke Michael Pavlovich of Russia (1798–1849) – son of Paul I of Russia and Sophie Dorothea of Württemberg. Owner of Pavlovsk between 1828 and 1849.

- Prince John Constantinovich of Russia (1886–1918) – son of Grand Duke Constantine Constantinovich of Russia and owner of Pavlovsk between 1915 and 1918. Born in Pavlovsk.

- Grand Duchess Maria Nikolaevna of Russia (1819–1876) – daughter of Emperor Nicholas I of Russia, sister of Alexander II and wife of Maximilian, Duke of Leuchtenberg. She was an art collector and President of the Imperial Academy of Arts of Saint Petersburg. Born in Pavlovsk.

- Maria Feodorovna (Sophie Dorothea of Württemberg) (1759–1828) – the second wife of Tsar Paul I of Russia and mother of Tsar Alexander I and Tsar Nicholas I of Russia. Owner of Pavlovsk between 1788 and 1828. Died in Pavlovsk.

- Olga Constantinovna of Russia (1851–1926) – queen consort of King George I of Greece and briefly in 1920, Queen Regent of Greece. The great-grandmother of Queen Sofia of Spain, the paternal grandmother of Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, and the great-grandmother of Charles, Prince of Wales. Born in Pavlovsk.

- Georg von Cancrin (1774–1845) – writer and statesman, General and Minister of Finances, died in Pavlovsk.

- Eugene Lanceray (1875–1946) – Russian graphic artist, painter, sculptor, mosaicist, and illustrator, born in Pavlovsk.

- Aleksandr Nikitenko (1804–1877) – literature critic and historian, academician of the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences. Died in Pavlovsk.

- Leonid Yanush (1897–1978) – a painter who lived in Pavlovsk between 1912 and 1927.

References

- "Об исчислении времени". Официальный интернет-портал правовой информации (in Russian). 3 June 2011. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- Darinskii, pp. 12–18

- ^ Darinskii, pp. 21–29

- Atlas of the Leningrad Region. Moscow. 1967. pp. 20–24.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|Publisher=ignored (|publisher=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - "Weather & Climate". pogoda.ru.net. Retrieved 2010-02-28.

- Darinskii, pp. 45–49

- "Пушкинский район в 2008 году, основные итоги экономического и социального развития (Pushkin region in 2008, main results of the economic and social development)". Administration of St. Petersburg. Retrieved 2010-02-28.

- http://www.viktur.ru/excursion/saint-petersburg/pavlovsk-196-285.html#19473

- "Охотничье-промысловые звери, птицы и рыбы (Animals, poultry and fish)". Atlas of the Leningrad Region. Moscow. 1967. pp. 36–37.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|Publisher=ignored (|publisher=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - В петербургской воде обнаружены запредельные концентрации токсичных веществ // REGIONS.RU 25.06.2008

- Колпино: заводская, но чистая окраина. "metro-Санкт-Петербург" № 151(1055) (29 August 2006), p. 3

- Федеральная служба государственной статистики (Federal State Statistics Service) (2004-05-21). "Численность населения России, субъектов Российской Федерации в составе федеральных округов, районов, городских поселений, сельских населённых пунктов – районных центров и сельских населённых пунктов с населением 3 тысячи и более человек (Population of Russia, its federal districts, federal subjects, districts, urban localities, rural localities—administrative centers, and rural localities with population of over 3,000)" (in Russian). Всероссийская перепись населения 2002 года (All-Russia Population Census of 2002). Federal State Statistics Service. . Retrieved 2009-08-19.

- "Pushkin". The People's Encyclopedia of Russian cities and regions "My City". Retrieved 2010-02-28.

- ^ НАСЕЛЁННЫЙ ПУНКТ / ПАВЛОВСК, Journal «Адреса»

- ^ Johann Gottlieb Georgi (1996). Описание российско-императорского столичного города САНКТ-ПЕТЕРБУРГ и достопримечательностей в окрестностях оного, с планом (Description of Russian imperial capital of St. Petersburg and attractions in the vicinity thereof, with a plan). St. Petersburg.: Лига. pp. 496–504.

- ^ Павловск (город в Ленинградской обл.), Great Soviet Encyclopedia on-line (in Russian)

- ^ Pavlovsk, Encyclopedia Britannica on-line

- Hayden 2005, p. 94

- Lanceray, pp. 51–52

- ^ Крепость "Бип" (Павловская крепость), НП"Петербургский Строительный Клуб"

- Kuchumov , A. M. (1970). Павловск. Путеводитель по дворцу-музею и парку (Pavlovsk. Palace and Park Guidebook). St. Petersburg: Лениздат.

- Hayden, p. 120

- Shvidkovsky, p. 281

- Shvidkovsky, 284

- Hayden, p. 120

- Lanceray, p. 85

- Lanceray, pp. 47–49

- ^ Музей / История Павловска (Museum/History of Pavlovsk), State Museum of Pavlovsk

- Schwartz V (1967). Пригороды Ленинграда (Suburbs of Leningrad). St. Petersburg – Moscow: Искусство.

- Царскосельская железная дорога (Tsarskoselskaya Railways), Промтехдепо

- http://family-history.ru/material/history/spb/spb_33.html

- Golyanov A. L. and Zakrevskaya G. P. Акционерное общество "Царскосельская железная дорога", Museum of Russian Railways, St. Petersburg (in Russian)

- Вокзал, Great Soviet Encyclopedia on-line (in Russian)

- Biography of Pantuhin on side pravoverie.ru Template:Ru icon

- Kroonenberg, Piet J. (1998). The Undaunted- The Survival and Revival of Scouting in Central and Eastern Europe. Geneva: Oriole International Publications. pp. 75–103. ISBN 2880520037.

- Schwarz W. (1967). The suburbs of Leningrad. St. Petersburg, Moscow: Искусство. pp. 123–189.

- УТРАЧЕННЫЕ КУЛЬТУРНЫЕ ЦЕННОСТИ. Павловский дворец (Lost Exhibits. Pavlovsk Palace), State Museum of Pavlovsk

- http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/540-007

- ПОСТАНОВЛЕНИЕ от 6 февраля 2006 г. N 117 О РЕЕСТРЕ НАЗВАНИЙ ОБЪЕКТОВ ГОРОДСКОЙ СРЕДЫ, (Decree of 6 February 2006 No. 117 on names of the municipal objects) Government of St. Petersburg (in Russian)

- г.Павловск (Санкт-Петербург), Russian Centre of Vexillology and Heraldry

- Герб города Павловск (Coat of arms of Pavlovsk) geraldika.ru

- Флаг города Павловск (Flag of Pavlovsk) geraldika.ru

- Санкт-Петербург: Энциклопедия. — СПб.: Бизнес-Пресса, 2006.

- Топонимическая энциклопедия Санкт-Петербурга. — СПб.: Информационно-издательское агентство ЛИК, 2002.

Bibliography

- Darinskii AV (1982). География Ленинграда (Geography of Leningrad). St. Petersburg: Lenizdat.

- Hayden, Peter (2005). Russian Parks and Gardens. Frances Lincoln. ISBN 0711224307.

- Lanceray, Nikolay (2006). Vincenzo Brenna (Винченцо Бренна) (in Russian). Saint Petersburg: Kolo. ISBN 5-901841-34-4.

- Shvidkovsky, Dmitry (2007). Russian architecture and the West. Yale University Press. ISBN 0300109121.

External links

- Official website about the Pavlovsk palace

- Pavlovsk Palace

- Pavlovsk Palace and Park – by Kuchumov

- Pavlovsk – information on garden history and design

- Autumnal views of Pavlovsk

- The Pavlovsk Park views

- Photo (1024x768). The Pavlovsk Palace.

- Photo (1024x768). The Pavlovsk Park.

- Bernier, Olivier (1 October 1989). "Russia's Reborn Splendor". New York Times. Retrieved 2006-12-15.

| Russian imperial palaces and residences | |

|---|---|

| Imperial residences | |

| Grand ducal residences | |

| Outside the Russian Federation | |

| In Crimea | |

| Historical | |

| Cities and towns under the jurisdiction of Saint Petersburg | |||

|---|---|---|---|