| Revision as of 16:30, 25 April 2011 editDicklyon (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Rollbackers477,164 edits Reverted to revision 425818191 by Epzcaw; literal en dash is better than the spelled out one. (TW)← Previous edit | Revision as of 16:31, 25 April 2011 edit undoEpzcaw (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users4,086 editsm Added information about earlier observation of Arago spotNext edit → | ||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

| The '''Huygens–Fresnel principle''' (named after ] ] ] and ] physicist ]) is a method of analysis applied to problems of ] propagation both in the ] and in near-field ]. | The '''Huygens–Fresnel principle''' (named after ] ] ] and ] physicist ]) is a method of analysis applied to problems of ] propagation both in the ] and in near-field ]. | ||

| Huygens<ref>Chr. Huygens, Traitė de la Lumiere (completed in 1678, published in Leyden in 1690)</ref> proposed that every point on which a luminous disturbance falls may be considered to be the centre of a new secondary spherical wave, and the sum of these secondary waves determines the form of the wavefront at any subsequent time. He assumed that the secondary waves travelled only in the forward direction, even though there was no logical reason to assume this. He was able to provide a qualitative explanation of linear and spherical wave propagation, and to derive the laws of reflection and refraction using this principle.<ref>OS Heavens and RW Ditchburn, Insight into Optics, 1987, Wiley & Sons, Chichester ISBN 0 471 92769 4</ref> His theory does not, however, explain ] effects. | Huygens<ref>Chr. Huygens, Traitė de la Lumiere (completed in 1678, published in Leyden in 1690)</ref> proposed that every point on which a luminous disturbance falls may be considered to be the centre of a new secondary spherical wave, and the sum of these secondary waves determines the form of the wavefront at any subsequent time. He assumed that the secondary waves travelled only in the forward direction, even though there was no logical reason to assume this. He was able to provide a qualitative explanation of linear and spherical wave propagation, and to derive the laws of reflection and refraction using this principle.<ref name = "Insight into Optics">OS Heavens and RW Ditchburn, Insight into Optics, 1987, Wiley & Sons, Chichester ISBN 0 471 92769 4</ref> His theory does not, however, explain ] effects. | ||

| Fresnel<ref> A. Fresnel, Ann Chim et Phys, (2), 1 (1816), Oeuvres, Vol.1, 89, 129 </ref> showed that Huygen's principle, together with his own principle of ] could explain both the rectilinear propagation of light, and also deviations from rectilinear propagation which occur when light encounters edges, apertures and screens – effects commonly referred to as ]. His model included additional assumptions about the phase and amplitude of the secondary waves, and also an arbitrary inclination factor. These assumptions had no physical foundations but led to predictions which agreed with many experimental observations, including the ]. | Fresnel<ref> A. Fresnel, Ann Chim et Phys, (2), 1 (1816), Oeuvres, Vol.1, 89, 129 </ref> showed that Huygen's principle, together with his own principle of ] could explain both the rectilinear propagation of light, and also deviations from rectilinear propagation which occur when light encounters edges, apertures and screens – effects commonly referred to as ]. His model included additional assumptions about the phase and amplitude of the secondary waves, and also an arbitrary inclination factor. These assumptions had no physical foundations but led to predictions which agreed with many experimental observations, including the ]. | ||

| ] was a member of the French Academy which reviewed Fresnel's work.<ref name = "Born and Wolf">Max Born and Emil Wolf, Principles of Optics, 1999, Cambridge University Press ISBN-13 978-0-521-64222-4 </ref> He used Fresnel's theory to predict that a bright spot will appear in the centre of the shadow of a small disc and deduced from this that the theory was incorrect. However, Arago, another member of the committee, performed the experiment and showed that the prediction was correct. This was one of the investigations which led to the victory of the wave theory of light over the then predominant corpuscular theory. | ] was a member of the French Academy which reviewed Fresnel's work.<ref name = "Born and Wolf">Max Born and Emil Wolf, Principles of Optics, 1999, Cambridge University Press ISBN-13 978-0-521-64222-4 </ref> He used Fresnel's theory to predict that a bright spot will appear in the centre of the shadow of a small disc and deduced from this that the theory was incorrect. However, Arago, another member of the committee, performed the experiment and showed that the prediction was correct. (Lisle had actually observed this fifty years earlier. <ref name = "Insight into Optics"/>) This was one of the investigations which led to the victory of the wave theory of light over the then predominant corpuscular theory. | ||

| The Huygens–Fresnel principle provides a good basis for understanding and predicting the wave propagation of light. However, this article<ref></ref> provides an interesting discussion of the limitations of the principle and also of different scientists' views as to whether it is an accurate representation of reality or whether "Huygens' principle actually does give the right answer but for the wrong reasons". | The Huygens–Fresnel principle provides a good basis for understanding and predicting the wave propagation of light. However, this article<ref></ref> provides an interesting discussion of the limitations of the principle and also of different scientists' views as to whether it is an accurate representation of reality or whether "Huygens' principle actually does give the right answer but for the wrong reasons". | ||

Revision as of 16:31, 25 April 2011

The Huygens–Fresnel principle (named after Dutch physicist Christiaan Huygens and French physicist Augustin-Jean Fresnel) is a method of analysis applied to problems of wave propagation both in the far-field limit and in near-field diffraction.

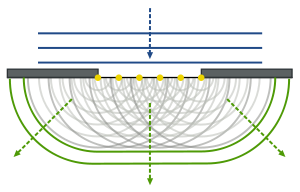

Huygens proposed that every point on which a luminous disturbance falls may be considered to be the centre of a new secondary spherical wave, and the sum of these secondary waves determines the form of the wavefront at any subsequent time. He assumed that the secondary waves travelled only in the forward direction, even though there was no logical reason to assume this. He was able to provide a qualitative explanation of linear and spherical wave propagation, and to derive the laws of reflection and refraction using this principle. His theory does not, however, explain diffraction effects.

Fresnel showed that Huygen's principle, together with his own principle of interference could explain both the rectilinear propagation of light, and also deviations from rectilinear propagation which occur when light encounters edges, apertures and screens – effects commonly referred to as diffraction. His model included additional assumptions about the phase and amplitude of the secondary waves, and also an arbitrary inclination factor. These assumptions had no physical foundations but led to predictions which agreed with many experimental observations, including the Arago spot.

Poisson was a member of the French Academy which reviewed Fresnel's work. He used Fresnel's theory to predict that a bright spot will appear in the centre of the shadow of a small disc and deduced from this that the theory was incorrect. However, Arago, another member of the committee, performed the experiment and showed that the prediction was correct. (Lisle had actually observed this fifty years earlier. ) This was one of the investigations which led to the victory of the wave theory of light over the then predominant corpuscular theory.

The Huygens–Fresnel principle provides a good basis for understanding and predicting the wave propagation of light. However, this article provides an interesting discussion of the limitations of the principle and also of different scientists' views as to whether it is an accurate representation of reality or whether "Huygens' principle actually does give the right answer but for the wrong reasons".

A simple example of the operation of the principle can be seen when two rooms are connected by an open doorway and a sound is produced in a remote corner of one of them. A person in the other room will hear the sound as if it originated at the doorway. As far as the second room is concerned, the vibrating air in the doorway is the source of the sound.

Mathematical expression of the principle

Consider the case of a point source located at a point P0, vibrating at a frequency f. The disturbance may be described by a complex variable U0 known as the complex amplitude. It produces a spherical wave with wavelength λ, wavenumber k =2π/λ. The complex amplitude of the primary wave at the point Q located at a distance r0 from P0 is given by

since the magnitude decreases in inverse proportion to the distance travelled, and the phase changes as k times the distance travelled.

Using Huygen's theory, and the principle of superposition of waves, the complex amplitude at a further point P is found by summing the contributions from each point on the sphere of radius r0. In order to get agreement with experimental results, Fresnel found that the individual contributions from the secondary waves on the sphere had to be multiplied by a constant, i/λ, and by an additional inclination factor, K(χ). The first assumption means that the secondary waves oscillate at a quarter of a cycle out of phase with respect to the primary wave, and that the magnitude of the secondary waves are in a ratio of 1:λ to the primary wave. He also assumed that K(χ) had a maximum value when χ=0, and was equal to zero when χ = π/2. The complex amplitude at P is then given by:

where S describes the surface of the sphere, and s is the distance between Q and P.

Fresnel used a zone construction method to find approximate values of K for the different zones, which enabled him to make predictions which were in agreement with experimental results.

The various assumptions made by Fresnel emerge automatically in Kirchhoff's diffraction formula, to which the Huygens–Fresnel principle can be considered to be an approximation. Kirchoff gives the following expression for K(χ):

This incorporates the quarter cycle phase shift and the reduced magnitude; K has a maximum value at χ = 0 as in the Huygens–Fresnel principle; however, K is not equal to zero at χ =π/2.

See also

- Green's function

- Green's theorem

- Green's identities

- Near-field diffraction pattern

- Double-slit experiment

- Knife-edge effect

- Fermat's principle

- Fourier optics

- Wave field synthesis

References

- Chr. Huygens, Traitė de la Lumiere (completed in 1678, published in Leyden in 1690)

- ^ OS Heavens and RW Ditchburn, Insight into Optics, 1987, Wiley & Sons, Chichester ISBN 0 471 92769 4

- A. Fresnel, Ann Chim et Phys, (2), 1 (1816), Oeuvres, Vol.1, 89, 129

- ^ Max Born and Emil Wolf, Principles of Optics, 1999, Cambridge University Press ISBN-13 978-0-521-64222-4

- Huygens' Principle

Further reading

Stratton, Julius Adams: Electromagnetic Theory, McGraw-Hill, 1941. (Reissued by Wiley – IEEE Press, ISBN 978-0-470-13153-4).

Categories: