| Revision as of 16:11, 8 March 2012 editDave1185 (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, File movers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers25,447 edits Reverted to revision 480825874 by Dave1185: reverted, per WP:BRD please take this to the talk page if you disagree, Stefan is not proficient in English and so is the content/text. (TW)← Previous edit | Revision as of 18:49, 8 March 2012 edit undoNigel Ish (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers77,018 edits →References: add refsNext edit → | ||

| Line 305: | Line 305: | ||

| * Curtis, Michael. ''The Middle East Reader''. Transaction Publishers, 1986. ISBN 0-88738101-4. | * Curtis, Michael. ''The Middle East Reader''. Transaction Publishers, 1986. ISBN 0-88738101-4. | ||

| * Deacon, Ray. ''Hawker Hunter - 50 Golden Years''. Feltham, UK: Vogelsang Publications, 2001. ISBN 0-9540666-0-X. | * Deacon, Ray. ''Hawker Hunter - 50 Golden Years''. Feltham, UK: Vogelsang Publications, 2001. ISBN 0-9540666-0-X. | ||

| * Donnet, Christophe. "A Farewell to Arms". ''World Air Power Journal''. Volume 20 Spring 1995. pp. 138–145. London: Aerospace Publishing. ISSN 0959-7050. ISBN 1 874023 49 2. | |||

| * Fowler, Will and Kevin Lyles. ''Britain's Secret War: The Indonesian Confrontation, 1962-66''. Osprey Publishing, 2006. ISBN 1-84603048-X. | * Fowler, Will and Kevin Lyles. ''Britain's Secret War: The Indonesian Confrontation, 1962-66''. Osprey Publishing, 2006. ISBN 1-84603048-X. | ||

| * Geiger, Till. UK, Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing Ltd, 2004. ISBN 0-75460287-7. | * Geiger, Till. UK, Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing Ltd, 2004. ISBN 0-75460287-7. | ||

| Line 318: | Line 319: | ||

| * Jeshurun, Chandran. ''The Growth of the Malaysian Armed Forces, 1963-73''. Institute of Southeast Asian, 1975. | * Jeshurun, Chandran. ''The Growth of the Malaysian Armed Forces, 1963-73''. Institute of Southeast Asian, 1975. | ||

| * Kavic, Lorne J. ''India's Quest for Security: Defence Policies, 1947-1965''. University of California Press, 1967. | * Kavic, Lorne J. ''India's Quest for Security: Defence Policies, 1947-1965''. University of California Press, 1967. | ||

| * Lake, Jon. " |

* Lake, Jon. "Hawker Hunter". ''Wings of Fame''. Volume 20, 2000. pp. 28–97. London: Aerospace Publishing. ISSN 1361-2034. ISBN 1 86184 053 5. | ||

| * Lake, Jon. "Last Bastion of the Hunter". '']'', Vol. 80, No 3, March 2011, pp. 74–79. Stamford, UK: Key Publishing. ISSN 0306-5634. | |||

| * Laming, Tim. Zenith Imprint, 1996. ISBN 07-6030260-X. | * Laming, Tim. Zenith Imprint, 1996. ISBN 07-6030260-X. | ||

| * Law, John. . Duke University Press, 2002. ISBN 0-82232824-0. | * Law, John. . Duke University Press, 2002. ISBN 0-82232824-0. | ||

Revision as of 18:49, 8 March 2012

| Hunter | |

|---|---|

| |

| Privately owned Hunter T.7 "Blue Diamond" | |

| Role | Fighter and ground attackType of aircraft |

| National origin | United Kingdom |

| Manufacturer | Hawker Siddeley |

| First flight | 20 July 1951 |

| Introduction | 1956 |

| Status | Active service with Lebanese Air Force |

| Primary users | Royal Air Force (historical) Indian Air Force (historical) Swedish Air Force (historical) Swiss Air Force (historical) |

| Number built | 1,972 |

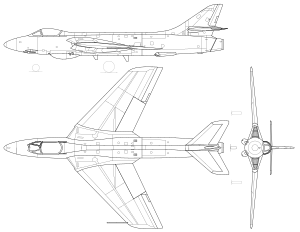

The Hawker Hunter is a subsonic British jet aircraft developed in the 1950s. The single-seat Hunter entered service as a manoeuvrable fighter aircraft, and later operated in fighter-bomber and reconnaissance roles in numerous conflicts. Two-seat variants remained in use for training and secondary roles with the Royal Air Force (RAF) and Royal Navy until the early 1990s. The Hunter was also widely exported, serving with 21 other air forces; 50 years after its original introduction it is still in active service, operating with the Lebanese Air Force.

On 7 September 1953, the modified first prototype broke the world air speed record, achieving 727.63 mph (1,171.01 km/h). Hunters were also used by two RAF display teams; the "Black Arrows", who on one occasion looped a record-breaking 22 examples in formation, and later the "Blue Diamonds", who flew 16 aircraft. Overall, 1,972 Hunters were produced by Hawker Siddeley and under licence. In British service, the aircraft was replaced by the Hawker Siddeley Harrier and the McDonnell Douglas Phantom.

Development

Origins

At the end of the Second World War, it was apparent that jet propulsion would be the future of fighter development. Many companies were quick to come up with airframe designs for this new means of propulsion, among these was Hawker Aviation's chief designer, Sydney Camm. The origins of the Hunter trace back to the Hawker Sea Hawk straight-wing carrier-based fighter, which had originally been marketed towards the Royal Air Force rather than the Fleet Air Arm of the Royal Navy; however the demonstrator Hawker P.1040 did not attract the RAF's interest. The Sea Hawk had a straight wing and used the Rolls-Royce Nene turbojet engine, both features that rapidly became obsolete.

Seeking better performance and fulfilment of the Air Ministry Specification E.38/46, Sydney Camm designed the Hawker P.1052, which was essentially a Sea Hawk with a 35-degree swept wing. First flying in 1948, the P.1052 demonstrated good performance and conducted several carrier trials, but did not warrant further development into a production aircraft. As a private venture, Hawker converted the second P.1052 prototype into the Hawker P.1081 with swept tailplanes, a revised fuselage, and a single jet exhaust at the rear. First flown on 19 June 1950, the P.1081 was promising enough to draw interest from the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF), but further development was stalled by difficulties with the engine reheat. The sole prototype was lost in a crash in 1951.

P.1067

In 1946, the Air Ministry issued Specification F.43/46 for a daytime jet-powered interceptor. Camm prepared a new design for a swept-winged fighter powered by the upcoming Rolls-Royce Avon turbojet. The Avon's major advantage over the Rolls-Royce Nene, used in the earlier Sea Hawk, was the axial compressor, which allowed for a much smaller engine diameter and provided greater thrust; this single engine gave roughly the same power as the two Rolls-Royce Derwents of the Gloster Meteors that would be replaced by the new fighter. In March 1948, the Air Ministry issued a revised Specification F.3/48, which demanded a speed of 629 mph (1,010 km/h) at 45,000 ft (13,700 m) and a high rate of climb, while carrying an armament of four 20 mm (0.79 in) or two 30 mm (1.18 in) cannon (rather than the large-calibre gun demanded by earlier specifications). Initially fitted with a single air intake in the nose and a T-tail, the project rapidly evolved into the more familiar Hunter shape. The intakes were moved to the wing roots to make room for weapons and radar in the nose, and a more conventional tail arrangement was devised as a result of stability concerns.

The P.1067 first flew from RAF Boscombe Down on 20 July 1951, powered by a 6,500 lbf (28.91 kN) Avon 103 engine. The second prototype, which was fitted with production avionics, armament and a 7,550 lbf (33.58 kN) Avon 107 turbojet, first flew on 5 May 1952. As an insurance against Avon development problems, Hawker modified the design to accommodate another axial turbojet, the 8,000 lbf (35.59 kN) Armstrong Siddeley Sapphire 101. Fitted with a Sapphire, the third prototype flew on 30 November 1952.

The Ministry of Supply ordered the Hunter into production in March 1950. The Hunter F.1, fitted with a 7,600 lbf (33.80 kN) Avon 113 turbojet, flew on 16 March 1953. The first 20 aircraft were, in effect, a pre-production series and featured a number of "one-off" modifications such as blown flaps and area ruled fuselage. On 7 September 1953, the sole Hunter Mk 3 (the modified first prototype, WB 188) flown by Neville Duke broke the world air speed record, achieving 727.63 mph (1,171.01 km/h) over Littlehampton. The record stood for under three weeks before being broken on 25 September 1953 by an RAF Supermarine Swift flown by Michael Lithgow.

Design

Overview

The Hunter was a conventional all-metal monoplane with a retractable tricycle landing gear. The pilot sat on a Martin-Baker 2H or 3H ejector seat, while the two-seat trainer version used Mk 4H ejection seats. The fuselage was of monocoque construction, with a removable rear section for engine maintenance. The engine was fed through triangular air intakes in the wing roots and had a single jetpipe in the rear of the fuselage. The mid-mounted wings had a leading edge sweep of 35° and slight anhedral, the tailplanes and fin were also swept. The aircraft's controls were conventional but powered. A single airbrake was fitted under the ventral rear fuselage on production models.

The definitive version of the Hunter was the FGA.9, on which the majority of export versions were based. Although the Supermarine Swift was initially viewed more favourably politically, the Hunter proved to be far more successful, having a long life due to its low maintenance and operating costs. The Hunter served with the RAF for over 30 years, and as late as 1996 hundreds were still in active service in various parts of the world.

Armament

The single-seat fighter version of the Hunter was armed with four 30 mm (1.18 in) ADEN cannon, with 150 rounds of ammunition per gun. The cannon and ammunition boxes were contained in a single pack that could be removed from the aircraft for rapid re-arming and maintenance. Unusually, the barrels of the cannon remained in the aircraft while the pack was removed and changed. In the two-seat version, either a single 30 mm ADEN cannon was carried or, in some export versions, two, with a removable ammunition tank. A simple EKCO ranging radar was fitted in the nose. Later versions of Hunter aircraft were fitted with SNEB Pods; these were 68 mm (2.68 in) rocket projectiles in 18-round Matra pods, providing an effective strike capability against ground targets.

Engine

The P.1067 first flew from RAF Boscombe Down on 20 July 1951, powered by a 6,500 lbf (28.91 kN) Avon 103 engine from an English Electric Canberra bomber. The second prototype was fitted with a 7,550 lbf (33.58 kN) Avon 107 turbojet. Hawker's third prototype was powered by an 8,000 lbf (35.59 kN) Armstrong Siddeley Sapphire 101. Production Hunters were fitted with either the Avon or the Sapphire engine.

Early on in the Hunter's service the Avon engines proved to have poor surge margins, and worryingly suffered compressor stalls when the cannon were fired, sometimes resulting in flameouts. The practise of "fuel dipping", reducing fuel flow to the engine when the cannon were fired, was a satisfactory solution. Although the Sapphire did not suffer from the flameout problems of the Avon and had better fuel economy, Sapphire-powered Hunters suffered many engine failures. The RAF elected to persevere with the Avon in order to simplify supply and maintenance, since the same engine was also used by the Canberra bomber.

The RAF sought more thrust than was available from the Avon 100 series; in response Rolls-Royce developed the Avon 200 series engine. This was an almost wholly new design, equipped with a new compressor to put an end to surge problems, an annular combustion chamber, and an improved fuel control system. The resulting Avon 203 produced 10,000 lbf (44.48 kN) of thrust, and was the engine for the Hunter F.6.

Operational history

Royal Air Force

The Hunter F.1 entered service with the Royal Air Force in July 1954. It was the first high-speed jet aircraft equipped with radar and fully powered flight controls to go into widespread service with the RAF. The Hunter replaced the Gloster Meteor, the Canadair Sabre, and the de Havilland Venom jet fighters in service. Initially, low internal fuel capacity restricted the Hunter's performance, giving it only a maximum flight endurance of about an hour. A tragic incident occurred on 8 February 1956, when a flight of eight Hunters was redirected to another airfield due to adverse weather conditions. Six of the eight aircraft ran out of fuel and crashed, killing one pilot.

Another difficulty encountered during the aircraft's introduction was the occurrence of surging and stalling with the Avon engines. The F.2, which used the Armstrong-Siddeley Sapphire engine, did not suffer from this issue. Further problems occurred; ejected cannon ammunition links had a tendency to strike and damage the underside of the fuselage, and diverting the gas emitted by the cannon during firing was another necessary modification. The original split-flap airbrakes caused adverse changes in pitch trim and were quickly replaced by a single ventral airbrake. This meant, however, that the airbrake could not be used for landings.

To address the problem of range, a production Hunter F.1 was fitted with a modified wing that featured bag-type fuel tanks in the leading edge and "wet" hardpoints. The resulting Hunter F.4 first flew on 20 October 1954, and entered service in March 1955. A distinctive Hunter feature added on the F.4 was the pair of blisters under the cockpit, which collected spent ammunition links to prevent airframe damage. Crews dubbed them "Sabrinas" after the contemporary movie star. The Sapphire-powered version of the F.4 was designated the Hunter F.5.

The RAF later received Hunters equipped with an improved Avon engine. The Avon 203 produced 10,000 lbf (44.48 kN) of thrust and was fitted to XF 833, which became the first Hunter F.6. Some other revisions on the F.6 included a revised fuel tank layout, the centre fuselage tanks being replaced by new ones in the rear fuselage; the "Mod 228" wing, which has a distinctive "dogtooth" leading edge notch to alleviate the pitch-up problem; and four "wet" hardpoints, finally giving the aircraft a good ferry range. The Hunter F.6 was given the company designation Hawker P.1099.

During the Suez Crisis of 1956, Hunters of No. 1 and No. 34 Squadrons based at RAF Akrotiri in Cyprus flew escort for English Electric Canberra bombers on offensive missions into Egypt. For most of the conflict the Hunters engaged in local air defence due to their lack of range.

During the Brunei Revolt in 1962, the Royal Air Force deployed Hunters and Gloster Javelins over Brunei to provide support for British ground forces; Hunters launched both dummy and real strafing runs on ground targets to intimidate and pin down rebels. In one event, several Bruneian and expatriate hostages were due to be executed by rebels; Hunter aircraft flew over Limbang while the hostages had been rescued by Royal Marines from 42 Commando in a fierce battle. In the following years of the Borneo Confrontation, Hunters were deployed along with other RAF aircraft in Borneo and Malaya.

The Hunter F.6 was retired from its day fighter role in the RAF by 1963, being replaced by the much faster English Electric Lightning interceptor. Many F.6s were then given a new lease of life in the close air support role, converting into the Hunter FGA.9 variant. The FGA.9 saw frontline use from 1960 to 1971, alongside the closely related Hunter FR.10 tactical reconnaissance variant. The Hunters were also used by two RAF display units; the "Black Arrows" of No. 111 Squadron who set a record by looping and barrel rolling 22 Hunters in formation, and later the "Blue Diamonds" of No. 92 Squadron who flew 16 Hunters.

In Aden in May 1964, Hunter FGA.9s and FR.10s of No. 43 Squadron RAF and No. 8 Squadron RAF were used extensively during the Radfan campaign against insurgents attempting to overthrow the Federation of South Arabia. SAS forces would routinely call in air strikes that required considerable precision, and, predominantly using 3-inch high explosive rockets and 30 mm ADEN cannon, the Hunter proved itself to be an able ground-attack platform. Both squadrons continued operations with their Hunters until the UK withdrew from Aden in November 1967.

Hunters were flown by No.63, No. 234 and No. 79 Squadrons acting in training roles for foreign and Commonwealth students. These remained in service until after the Hawk T.1 entered service in the mid-1970s. Two-seat trainer versions of the Hunter, the T.7 and T.8, remained in use for training and secondary roles by the RAF and Royal Navy until the early 1990s; when the Blackburn Buccaneer retired from service, the requirement for Hunter trainers was nullified and consequently all were retired.

Indian Air Force

India arranged for Hunters to be purchased in 1954 as a part of a wider arms deal with Britain, placing an order for 140 Hunter single-seat fighters; simultaneous to an announcement by Pakistan of its own purchase of several North American F-86 Sabre jet fighters. The Indian Air Force (IAF) were the first to operate the Hunter T.66 trainers, placing an initial order in 1957; the more powerful engine was considered beneficial in a hot environment, allowing for greater takeoff weights. During the 1960s, Pakistan investigated the possibility of buying as many as 40 English Electric Lightnings; however, Britain was not enthusiastic about the potential sales opportunity because of the damage it would do to its relations with India, which at the time was still awaiting the delivery of large numbers of ex-RAF Hunters.

During the Sino-Indian War in 1962, the Hunter's superiority over the Chinese MiGs gave India a strategic advantage; and deterred the use of Ilyushin Il-4 bombers from attacking targets within India. The Hunter would also be a major feature in the escalation of the Indo-Pakistani War of 1965; along with the Gnat the Hunter was the primary air defence fighter of India, and regularly engaged in dogfights with Pakistani F-86 Sabres. The aerial war saw both sides conducting thousands of sorties in a single month. Despite the intense fighting, the conflict was effectively a stalemate.

Hunters flown by the IAF extensively operated in the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971; at the start, India had six combat-ready squadrons of Hunters. In the aftermath of the conflict, Pakistan claimed to have shot down 32 Indian Hunters overall. Pakistani infantry and armoured forces attacked the Indian outpost of Longewala in an event now known as the Battle of Longewala. Six IAF Hunters stationed at Jaisalmer Air Force Base were able to halt the Pakistani advance at Longewala by conducting non-stop bombing raids. They attacked Pakistani tanks, armoured personnel carriers and gun positions; and created a sense of chaos on the battlefield, resulting in the Pakistani retreat. Hunters were also used for many ground attack missions and raids into Pakistan, most notoriously used in the bombing of the Attock Oil refinery, to limit Pakistani fuel supplies during the war.

The Hunters were not used by India in the 1999 Kargil War, and the last IAF Hunter was phased out of service in 2001. The Hunter was replaced by the Sukhoi Su-30MKI.

Swiss Air Force

The Swiss Air Force adopted the Hawker Hunter in 1961, many of them refurbished and modernised ex-RAF aircraft, to replace earlier aircraft such as the De Havilland Venom. The Hunter survived the procurement efforts of several aircraft promising to be superior; in the case of the Dassault Mirage III this was due to excessive cost overruns and poor project management rather than the attributes of the Hunter itself. A second competition between the Mirage III and the LTV A-7 Corsair II concluded in neither winning a contract; additional Hunters were purchased to meet the demand instead.

By 1975, plans were laid to replace the Hunter in the air-to-air role with a more modern fighter aircraft, the Northrop F-5E Tiger II. The Hunter remained in a key role within the Swiss Air Force; like the RAF's Hunter it transitioned to be the country's primary ground attack platform; and would remain in this role until the Swiss government purchased 32 McDonnell Douglas F/A-18 Hornets as replacements in the late 1990s. The Patrouille Suisse, the Swiss Air Force's display team, performed in Hunters for many years; like the rest of the Air Force they have now transitioned to flying F-5 aircraft.

Republic of Singapore Air Force

Singapore was an enthusiastic operator of the Hunter, first ordering the aircraft in 1968 during a massive expansion of the city-state's armed forces; deliveries began in 1971 and were completed by 1973. At the time, considerable international controversy was generated as Britain (and, as was later revealed, the U.S.) had refused to sell Hunters to neighbouring Malaysia, sparking fears of a regional arms race and accusations of favouritism. The Republic of Singapore Air Force (RSAF) eventually received 46 refurbished Hunters to equip two squadrons.

In the late 1970s, the Singaporean Hunter fleet was upgraded and modified by Lockheed Aircraft Services Singapore (LASS) with an additional hardpoint under the forward fuselage and another two inboard pylons (wired only for AIM-9 Sidewinders) before the main gears, bringing to a total of seven hardpoints for external stores and weapons delivery. As a result of these upgrades, they were redesignated as FGA.74S, FR.74S and T.75S. The RSAF Black Knights, Singapore Air Force's aerobatic team, flew Hunters from 1973 until 1989.

By 1991, Singapore's fleet of combat aircraft included the General Dynamics F-16 Fighting Falcon, the Northrop F-5 Tiger II, as well as the locally modernised and upgraded ST Aerospace A-4SU Super Skyhawk; the Hunters were active but obsolete in comparison. The type was finally retired and phased out of service in 1992, with the 21 surviving airframes being sold off to an Australian warbird broker, Pacific Hunter Aviation Pty, in 1995.

Others

Africa

During the 1950s, the Royal Rhodesian Air Force was an important export customer of Britain, purchasing not only Hunters but De Havilland Vampires and Canberra bombers as well. The Royal Rhodesian Air Force used its Hunter FGA.9s extensively against ZANU/ZAPU insurgents in the late 1960s and throughout the 1970s, occasionally engaging in cross-border strikes. The Air Force of Zimbabwe used its Hunters inherited from the Rhodesian Air Force to support Laurent Kabila during the Second Congo War, and were reported to be involved in the fighting in Mozambique. During Siad Barre's regime in present day Somalia, Hunters were used, often flown by former Rhodesian Air Force pilots, to conduct bombing missions during the civil war in the late 1980s.

Belgium and the Netherlands

The Belgian Air Force received 112 Hunter F.4s between 1956 and 1957 to replace the Gloster Meteor F.8. The aircraft were built under licence in both Belgium and the Netherlands in a joint programme, some using U.S. offshore funding. SABCA and Avions Fairey built 64 aircraft in Belgium and a further 48 were built in the Netherlands by Fokker. The Hunters were used by Nos. 1, 3 and 9 Wings but did not serve for long; the aircraft with 1 Wing were replaced in 1958 by the Avro Canada CF-100 Canuck, and most were scrapped afterwards.

The Belgian and Dutch governments subsequently ordered the improved Hunter F.6, with Nos. 1, 7 and 9 Wings of the Belgian Air Force receiving 112 Fokker-built aircraft between 1957 and 1958. Although built in the Netherlands, 29 aircraft had been assembled from kits in Belgium by SABCA and 59 by Avions Fairey, and were operated by 7 and 9 Wings. No. 9 Wing was disbanded in 1960, and by 1963 the Hunter squadrons in 7 Wing had also been disbanded. A large number of the surviving Hunters were sold to Hawker Aircraft and re-built for re-export to India and Iraq, with others to Chile, Kuwait and Lebanon.

Middle East

Between 1964 and 1975, both Britain and France delivered significant quantities of arms, including Hunters, to Iraq. The Hunters were far more effective in fighting guerrilla activity than the Russian MiGs then operated by Iraq. In 1967, Hunters of the Iraqi Air Force saw action after the Six-Day War between Israel and several neighbouring Arab nations. During the War of Attrition Iraqi Hunters usually operated from bases in Egypt and Syria. While flying a Hunter from Iraqi Airbase H3, Flight Lieutenant Saiful Azam, on exchange from the Pakistan Air Force, shot down two Israeli jets including a Mirage IIIC. Some missions were also flown by the Royal Jordanian Air Force, but most of the Jordanian Hunters were destroyed on the ground on the first day of the Six-Day War. Replacement Hunters for Jordanian service were acquired from both Britain and Saudi Arabia in the war's aftermath.

The Lebanese Air Force operated Hawker Hunters from 1958. A Lebanese Hunter shot down an Israeli jet over Kfirmishki in the early 1960s; its pilot was captured by the Lebanese Armed Forces. One Hunter was shot down on the first day of the Six-Day War by the Israeli Air Force. They were used infrequently during the Lebanese Civil War, and eventually fell out of usage and went into storage during the 1980s.

In August 2007, the Lebanese Armed Forces planned to put its Hunters back into service following the 2007 Lebanon conflict, to deal with Fatah al-Islam militants in the Nahr el-Bared camp north of Tripoli. However, the programme was delayed by lack of spare parts for the aircraft, notably cartridges for the Martin-Baker ejection seats. On 12 November 2008, the Lebanese Air Force returned the Hunter into service, 50 years after its original introduction. There have been recent military exercises conducted with Hunters, such as those that took place on 12 July 2010.

South America

Chile undertook the acquisition of Hunters from Britain in the 1960s for use in the Chilean Air Force. Two years after delivery was completed in 1971, the Hunters were used by military officers in the 1973 Chilean coup d'état to overthrow the socialist president of Chile, Salvador Allende, on 11 September 1973. Coup leaders had ordered the Hunters to relocate to Talcahuano on 10 September. The following morning, they engaged in bombing missions against the presidential palace, Allende's house in Santiago, and several radio stations loyal to the government.

The purchase of Hunters by Chile may have been a factor in the decision by the Peruvian Air Force to acquire Hunters of their own. Britain was keen to sell to Peru as the decision to sell Hunters to Chile became a controversial political issue for the British government following the Coup, and the sale would uphold Britain's concept of regional 'balancing'.

Sweden

In the early 1950s, the Swedish Air Force saw the need for an interceptor that could reach enemy bombers at a higher altitude than the J 29 Tunnan that formed the backbone of the fighter force. A contract for 120 Hawker Hunters Mk 50s (equivalent to the Mk 4) was therefore signed on 29 June 1954 and the first aircraft was delivered on 26 August 1955. The model was designated J 34 and was assigned to the F 8 and F 18 wings that defended Stockholm. The J 34 was armed with four 30 mm (1.18 in) cannons and two Sidewinders. The Swedish Air Force's aerobatic team Acro Hunters used five J 34s during the late 1950s. The J 34s were gradually replaced by supersonic J 35 Draken and re-assigned to less prominent air wings, F 9 in Gothenburg and F 10 in Ängelholm, during the 1960s.

A project to improve the performance of the J 34 resulted in several Hunters being fitted with a Swedish-designed afterburner in 1958. While this significantly increased the engine's thrust, there was little improvement in performance, so the project was shelved, and the last J 34s were retired in 1969.

Variants

Further information: ]Operators

Military

Abu Dhabi

Abu Dhabi Belgium

Belgium Chile

Chile Denmark

Denmark Iraq

Iraq India

India Jordan

Jordan Kenya

Kenya Kuwait

Kuwait Lebanon

Lebanon Netherlands

Netherlands Oman

Oman Peru

Peru Qatar

Qatar Rhodesia

Rhodesia Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia Singapore

Singapore Somalia

Somalia Sweden

Sweden Switzerland

Switzerland United Kingdom

United Kingdom Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe

Civil

- Airborne Tactical Advantage Company

- Based in Newport News, VA, ATAC operates Mk.58 Hunters for tactical air training.

- Apache Aviation

- Operates from Istres in southern France. Three examples (2× single-seater and 1× two-seater) contracted by French Navy.

- Delta Jets

- Operated between 1995 to 2010 from Kemble Airport near Cirencester, England with three operational Hunters. The company went into liquidation in 2010

- Dutch Hawker Hunter Foundation.

- Operates a Hunter T.8C two-seat in classic RNLAF paint and a single-seat Hunter F.6A with the original Dutch colours and markings. The Hunter T.8C and the F.6A are based at Leeuwarden Air Base in the Netherlands.

- Embraer

- Operates an ex-Chilean Air Force Hunter T.72 as a flight test chase plane.

- Hawker Hunter Aviation.

- Based at RAF Scampton, it operates a fleet of 12 Mk 58 and three two-seaters (T.7 and T.8), as well as other aircraft to provide "high speed Aerial Threat Simulation, Mission Support Training and Trials Support Services".

- Hunter Flying Ltd.

- Based at Exeter International Airport in England, Hunter Flying Ltd maintain over 15 privately owned examples of the Hunter.

- Lortie Aviation Inc.

- This company, (formerly Northern Lights Combat Air Support) based in Quebec City, Canada, owns and operates 12 Hunters (mainly ex-Swiss F.58 variants) for military co-operation duties such as FAC training, radar calibration, radar target facilities and missile simulation.

- Thunder City

- Seven Hunters are based at Thunder City at Cape Town International Airport in South Africa.

Specifications (Hunter F.6)

| External image | |

|---|---|

Data from The Great Book of Fighters

General characteristics

- Crew: One

Performance

- Thrust/weight: 0.56

Armament

- Guns: 4× 30 mm (1.18 in) ADEN cannons in a removable gun pack with 150 rpg

- Hardpoints: 4 underwing with a capacity of 7,400 lb (3,400 kg), with provisions to carry combinations of:

- Rockets:

- 4× Matra rocket pods (each with 18 × SNEB 68 mm (2.68 in) rockets) or

- 24× Hispano SURA R80 80 mm (3.15 in) rockets

- Missiles:

- Bombs: a variety of unguided iron bombs

- Other: 2× 230 Gallon drop tanks for extended range/loitering time

- Rockets:

Avionics

See also

Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

References

- Notes

- Originally it had been planned to task the Folland Gnat with the low-level ground attack missions; however, Hawker converted two aircraft and demonstrated in trials that the Hunter was able to significantly out-perform the Gnat, thus the Hunter was selected instead.

- Nikita Khrushchev had become distrustful of Mao Zedong, and withheld major technologies such as new Soviet fighter aircraft, thus China's MiGs were very early jet aircraft only.(See Sino–Soviet split)

- The IAF had a total of 118 Hunters at their disposal at the beginning of the 1965 conflict.

- Each squadron typically had 16 aircraft, meaning India had roughly 96 Hunters available.

- The Hunters were not fitted with night vision equipment, and as such were delayed from conducting combat missions until dawn.

- Note also the additional hardpoints and the ADEN gun ports which have been faired over to protect this museum piece against the weather.

- The breakdown of Singapore's Hunter fleet being 12 × FGA.74, 26 × FR.74A/B and 8 × T.75/A (excluding one T.75A lost in an accident before delivery).

- Israeli sources state that the Mirage III and the Hunter were well matched, the Mirage having more advanced avionics while the Hunter had greater agility.

- Citations

- Mason 1991, pp. 355–356.

- Griffin 2006, p. 15.

- Mason 1991, pp. 368–370.

- Mason 1991, p. 373.

- Jackson 1982, p. 8.

- Mason 1992, p. 368.

- Jackson 1982, p. 10.

- ^ Jackson 1982, p. 11. Cite error: The named reference "Jacksonp11" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Griffin 2006, pp. 17-18. Cite error: The named reference "Griffin 17-18" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- Griffin 2006, pp. 18-19.

- "R.Ae.C. Award Winners." Flight International, 5 February 1954. Retrieved: 3 November 2009.

- "Speed Record Again Broken?" Saskatoon Star-Phoenix, 25 September 1953.

- Geiger 2004, p. 170.

- Laming 1996, p. 53.

- ^ Laming 1996, p. 51.

- Mason 1991, p. 375.

- ^ Griffin 2006, p. 27.

- ^ Law 2002, pp. 211-212.

- ^ Griffin 2006, p. 19.

- ^ Griffin 2006, pp. 25-26.

- ^ Griffin 2006, p. 26.

- ^ "Hawker Hunter FGA9 Aircraft History - Post-World War Two Aircraft". RAF Museum, Retrieved: 9 April 2011.

- "Hunter Aircraft (Report of Inquiry)". Hansard. 25 April 1956. Retrieved 2009-08-23.

- Law 2002, p. 167.

- Griffin 2006, p. 25.

- Skardon 2010, p. 478.

- Griffin 2006, p. 93.

- Fowler and Lyles 2006, p. 10.

- ^ Fowler and Lyles 2006, p. 5.

- Moulton, J.L. The Royal Marines. London: Leo Cooper, 1972. ISBN 978-0-85052-117-7.

- "Black Arrows History" Royal Air Force, Retrieved: 9 April 2011.

- Scholey and Forsyth 2008, pp. 135, 137.

- Scholey and Forsyth 2008, p. 169.

- Griffin 2006, p. 30.

- Fricker and Green 1958, p. 160.

- Kavic 1967, p. 109.

- Griffin 2006, p. 31.

- Pytharian 2000, p. 130.

- ^ Sieff 2009, p. 83.

- Sieff 2009, p. 84.

- Coggins 2000, p. 163.

- Mohan and Chopra 2005, p. 41.

- Singh, Jasjit. "The 1965 India-Pakistan War: IAF’s Ground Reality". The Sunday Tribune, 6 May 2007.

- Coggins 2000, pp. 163-164.

- ^ Coggins 2000, p. 165.

- Coggins 2000, p. 166.

- ^ Nordeen 1985, p. 100.

- Jackson 1990, p. 128.

- Datta, Saikat."Rest Over, Upgraded Sukhois Set to Fly Again". Indian Express. 27 September 2002.

- ^ Martin 1996, p. 321.

- Martin 1996, p. 322.

- Senior 2003, pp. 33-34, 74.

- Patrouille Suisse. Swiss Air Force. Retrieved 14 April 2011.

- Jeshurun 1975, pp. 18-19.

- ^ Peter, Atkins (November 1994). "Singapore or Bust". Air Forces Monthly (67). Key Publishing Ltd. ISSN 0955-7091.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - "RSAF First Squadron Hunter". Pacific Hunter Aviation. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- "Black Knights - History". Republic of Singapore Air Force, Accessed: 15 April 2010.

- "Singapore Facts and Pictures". Ministry of Culture, 1991. p. 107.

- "Hunter for sale". Pacific Hunter Aviation. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- Petter-Bowyer 2005, p. 52.

- "Fireforce Exposed: the Rhodesian Security Forces and their Role in Defending White Supremacy". Anti-Apartheid Movement, 1979. p. 51.

- Beckett and Pimlott 1985, p. 168.

- Lefebvre 1992, p. 251.

- ^ Jackson 1977, pp. 63-73

- Jackson 1990, p. 84.

- Curtis 1986, p. 128

- Pollack 2002, p. 294.

- Pollack 2002, p. 295.

- Bahl and Syed 2003, p. 201.

- "وقائع العرض العسكري الذي سيقام بمناسبة عيد الاستقلال ."Template:Ar icon lebarmy.gov.lb, 21 November 2008. Retrieved: 23 July 2009.

- Hirst 2010, pp. 100-101.

- Rolland 2003, p. 186.

- "Helicopter bombs." yalibnan.com. Retrieved: 23 July 2009.

- ^ Lake Air International March 2011, p. 77.

- "Hawker Hunters to Exercise in Lebanese Airspace." naharnet.com. Retrieved: 22 August 2010.

- ^ Arce 2004, p. 17.

- Phythian 2000, p. 129.

- Phythian 2000, pp. 105-106, 130.

- ^ Jackson 1982, p.70.

- Mason 1991, p. 600.

- ^ Griffin 2006, p. 431.

- Mason 1991, pp. 398–399.

- Jackson 1990, p. 131.

- Jackson 1990, p. 17.

- ^ Jackson 1990, p. 137.

- Jackson 1990, p. 138.

- Jackson 1990, p. 139.

- "Aircraft". Airborne Tactical Advantage Company. Retrieved: 02 November.

- "Fleet". Apache Aviation. Retrieved: 14 April 2011.

- Delta Jets. Retrieved: 6 March 2010.

- "Dutch Hawker Hunter Foundation." dutchhawkerhunter.nl. Retrieved: 3 November 2009.

- "Embraer liveried Hunter." airliners.net. Retrieved: 3 November 2009.

- HHA Aircraft Technical Data hunterteam.com. Retrieved: 15 April 2011.

- Russell, Mark. "Hunter Flying." Hunter Flying Ltd., October 2008. Retrieved: 6 December 2009.

- "Lortie Aviation Inc." Lortie Aviation. Retrieved: 6 December 2009.

- "Cape Town Jets: Thunder City." Incredible Adventures, 2009. Retrieved: 7 October 2009.

- Green, William and Gordon Swanborough. The Great Book of Fighters. St. Paul, Minnesota: MBI Publishing, 2001. ISBN 0-7603-1194-3.

- "Hispano SURA R80 rockets." Flight International. 30 August 1962, p. 159.

- Bibliography

- Arce, Luz. The Inferno: A Story of Terror and Survival in Chile. University of Wisconsin Press, 2004. ISBN 0-29919554-6.

- Bahl, Taru and M.H. Syed. Encyclopaedia of the Muslim World. Anmol Publications Ltd., 2003. ISBN 8-12611419-3.

- Beckett, Ian Frederick William and John Pimlott. Armed Forces & Modern Counter-Insurgency. Taylor & Francis, 1985. ISBN 0-70993236-7.

- Bradley, Paul. The Hawker Hunter: A Comprehensive Guide. Bedford, UK: SAM Publications, 2009. ISBN 0-95518589-0.

- Coggins, Edward V. Wings That Stay On. Turner Publishing Company, 2000. ISBN 1-56311568-9.

- Curtis, Michael. The Middle East Reader. Transaction Publishers, 1986. ISBN 0-88738101-4.

- Deacon, Ray. Hawker Hunter - 50 Golden Years. Feltham, UK: Vogelsang Publications, 2001. ISBN 0-9540666-0-X.

- Donnet, Christophe. "A Farewell to Arms". World Air Power Journal. Volume 20 Spring 1995. pp. 138–145. London: Aerospace Publishing. ISSN 0959-7050. ISBN 1 874023 49 2.

- Fowler, Will and Kevin Lyles. Britain's Secret War: The Indonesian Confrontation, 1962-66. Osprey Publishing, 2006. ISBN 1-84603048-X.

- Geiger, Till. Britain and the Economic Problem of the Cold War: The Political Economy and the Economic Impact of the British Defence Effort, 1945-1955. UK, Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing Ltd, 2004. ISBN 0-75460287-7.

- Green, William and John Fricker. The Air Forces of the World: Their History, Development, and Present Strength. Macdonald, 1958.

- Griffin, David. J. Hawker Hunter 1951 to 2007. US, Morrisville: Lulu Enterprises, 2006. ISBN 1-43030593-2.

- Hannah, Donald. Hawker FlyPast Reference Library. Stamford, Lincolnshire, UK: Key Publishing Ltd., 1982. ISBN 0-946219-01-X.

- "Hawker Hunter." Vliegend in Nederland 4 (in Dutch). Eindhoven, Netherlands: Flash Aviation, 1990. ISBN 978-90-71553-09-7.

- Hirst, David. Beware of Small States: Lebanon, Battleground of the Middle East. Nation Books, 2010. ISBN 1-56858422-9.

- Jackson, Paul A. Belgian Military Aviation 1945-1977. Hinckley, Leicestershire, UK: Midland Counties Publications, 1977. ISBN 0 904597 06 7.

- Jackson, Robert. Hawker Hunter: The Operational Record, Volume 31. Smithsonian Institution Press, 1990. ISBN 0-87474377-X.

- Jackson, Robert. Modern Combat Aircraft 15, Hawker Hunter. Shepperton, Surrey, UK: Ian Allan, 1982. ISBN 0-7110-1216-4.

- James, Derek N. Hawker: Aircraft Album No. 5. New York: Arco Publishing Company, 1973 (First published in the UK by Ian Allan in 1972). ISBN 0-668-02699-5.

- Jeshurun, Chandran. The Growth of the Malaysian Armed Forces, 1963-73. Institute of Southeast Asian, 1975.

- Kavic, Lorne J. India's Quest for Security: Defence Policies, 1947-1965. University of California Press, 1967.

- Lake, Jon. "Hawker Hunter". Wings of Fame. Volume 20, 2000. pp. 28–97. London: Aerospace Publishing. ISSN 1361-2034. ISBN 1 86184 053 5.

- Lake, Jon. "Last Bastion of the Hunter". Air International, Vol. 80, No 3, March 2011, pp. 74–79. Stamford, UK: Key Publishing. ISSN 0306-5634.

- Laming, Tim. Fight's On: Airborne with the Aggressors. Zenith Imprint, 1996. ISBN 07-6030260-X.

- Law, John. Aircraft Stories: Decentering the Object in Technoscience. Duke University Press, 2002. ISBN 0-82232824-0.

- Lefebvre, Jeffery A. Arms for the Horn: U.S. Security Policy in Ethiopia and Somalia, 1953-1991. University of Pittsburgh, 1992. ISBN 0-82298533-0.

- Martin, Stephen. The Economics of Offsets: Defence Procurement and Countertrade. Routledge, 1996. ISBN 3-71865782-1.

- Mason, Francis K. Hawker Aircraft since 1920. London: Putnam, 1991. ISBN 0-85177-839-9.

- Mason, Francis K. The British Fighter since 1912. Annapolis, Maryland, USA: Naval Institute Press, 1992. ISBN 1-55750-082-7.

- McLelland, Tim. The Hawker Hunter. Manchester, UK: Crécy Publishing Ltd., 2008. ISBN 978-0-85979-123-6.

- Mohan, P. V. S. Jagan and Samir Chopra. The India-Pakistan Air War of 1965. Manohar, 2005. ISBN 8-17304641-7.

- Nordeen, Lon O. Air Warfare in the Missile Age, US: Smithsonian Institution, 1985.

- Petter-Bowyer, Peter J. H. Winds of Destruction: The Autobiography of a Rhodesian Combat Pilot. Johannesburg, South Africa: 30° South Publishers, 2005. ISBN 0-958-48903-3.

- Pollack, Kenneth Michael. Arabs at War: Military Effectiveness, 1948-1991, University of Nebraska Press, 2002. ISBN 0-80323733-2.

- Phythian, Mark. The Politics of British Arms Sales since 1964. Manchester University Press, 2000. ISBN 0-71905907-0.

- Rolland, John C. Lebanon: Current Issues and Background. Nova Publishers, 2003. ISBN 1-59033871-5.

- Scholey, Pete and Frederick Forsyth. Who Dares Wins: Special Forces Heroes of the SAS. Osprey Publishing, 2008. ISBN 1-84603311-X.

- Senior, Tim. The Air Forces Book of the F/A-18 Hornet. Zenith Imprint, 2003. ISBN 0-94621969-9.

- Sieff, Martin. Shifting Superpowers: The New and Emerging Relationship Between the United States, China, and India. Cato Institute, 2009. ISBN 1-93530821-1.

- Skardon, C Philip. A Lesson for Our Times: How America Kept the Peace in the Hungary-Suez Crisis of 1956. AuthorHouse, 2010. ISBN 1-42089102-2.

- Winchester, Jim, ed. "Hawker Hunter." Military Aircraft of the Cold War (The Aviation Factfile). London: Grange Books plc, 2006. ISBN 1-84013-929-3.

External links

- The FRADU Hunters web-site

- Article on Gütersloh Hunters

- Hunter Flying Ltd

- Delta Jets

- Hawker Hunter Aviation

- "Hawker-Hunter-1951to2007," Yahoo Group featuring hundreds of Hunter photos

- Warbird Alley's Hunter information page

- Hawker Hunter development

| Swedish military aircraft designations 1926–current | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| By role |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Post–1940 unified sequence | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Italics Pre-unification designations • Assigned to multiple types • Not unified with main sequence | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aviation lists | |

|---|---|

| General | |

| Military | |

| Accidents / incidents | |

| Records | |