| Revision as of 05:42, 30 April 2012 editBruceGrubb (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users8,222 edits →The James passage← Previous edit | Revision as of 16:19, 30 April 2012 edit undoReject censorship (talk | contribs)7 edits removing POV pushing by Catholic fundamentalistsNext edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

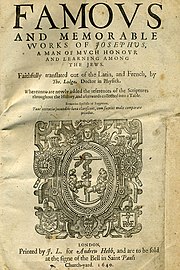

| ]'']] | ]'', the only Josephus work which includes references to Jesus.]] | ||

| The extant manuscripts of the writings of the 1st century ]-] ] include references to ''']''' and the ].{{sfn|Feldman|Hata|1987|pp=54-57}}{{sfn|Flavius Josephus|Maier|1995|pp=284-285}} Josephus' '']'', written around 93–94 AD, includes two references to Jesus in Books ] and ] and a reference to ] in Book ].{{sfn|Feldman|Hata|1987|pp=54-57}}{{sfn|Flavius Josephus|Maier|1995|p=12}} | |||

| The overwhelming majority of modern scholars consider the reference in ] of the ''Antiquities'' to "the brother of Jesus, who was called Christ, whose name was James" to be authentic and to have the highest level of authenticity among the references of Josephus to Christianity.{{sfn|Van Voorst|2000|p=83}}{{sfn|Feldman|Hata|1987|pp=54-57}}{{sfn|Flavius Josephus|Maier|1995|pp=284-285}}{{sfn|Bauckham|1999|pp=199-203}}{{sfn|Painter|2005|pp=134-141}} Almost all modern scholars consider the reference in ] of the ''Antiquities'' to the imprisonment and death of ] to be also authentic.{{sfn|Evans|2006|pp=55-58}}{{sfn|Bromiley|1982|pp=694-695}}{{sfn|White|2010|p=48}} | |||

| Scholars have differing opinions on the total or partial authenticity of the reference in ] of the ''Antiquities'' to the execution of Jesus by ], a passage usually called the '']''.{{sfn|Schreckenberg|Schubert|1992a|pp=38-41}}{{sfn|Feldman|Hata|1987|pp=54-57}} The general scholarly view is that while the ''Testimonium Flavianum'' is most likely not authentic in its entirety, it is broadly agreed upon that it originally consisted of an authentic nucleus with a reference to the execution of Jesus by Pilate which was then subject to Christian interpolation,{{sfn|Schreckenberg|Schubert|1992a|pp=38-41}}{{sfn|Kostenberger|Kellum|Quarles|2009|pp=104-108}}{{sfn|Evans|2001|p=316}}{{sfn|Wansbrough|2004|p=185}}{{sfn|Dunn|2003|p=141}} Although the exact nature and extent of the Christian redaction remains unclear<ref>Wilhelm Schneemelcher, Robert McLachlan Wilson, ''New Testament Apocrypha: Gospels and Related Writings'', page 490 (James Clarke & Co. Ltd, 2003). ISBN 0-664-22721-X</ref> there is broad consensus as to what the original text of the ''Testimonium'' by Josephus would have looked like.{{sfn|Dunn|2003|p=141}} | |||

| The references found in ''Antiquities'' have no parallel texts in the other work by Josephus such as the '']'', written 20 years earlier, but some scholars have provided explanations for their absence.{{sfn|Feldman|1984|p=826}} A number of variations exist between the statements by Josephus regarding the deaths of James and John the Baptist and the ] accounts.{{sfn|Evans|2006|pp=55-58}}{{sfn|Painter|2005|pp=143–145}} Scholars generally view these variations as indications that the Josephus passages are not interpolations, for a Christian interpolator would have made them correspond to the New Testament accounts, not differ from them.{{sfn|Evans|2006|pp=55-58}}{{sfn|Eddy|Boyd|2007|p=130}}{{sfn|Painter|2005|pp=143–145}} | |||

| {{Jesus}} | {{Jesus}} | ||

| ''']''' (c.37 – 100, also known as ''Yosef ben Matityahu'', ] יוסף בן מתתיהו, Joseph son of Matthias) was a renowned 1st-century ]. Despite being a Roman apologist, his writings are seen as providing an important historical and cultural background for the era described in the ]. Books 18 to 20 of the ''Antiquities of the Jews'' are the most important in this regard.<ref>{{cite book|title=Flavius Josephus|author=], Steve Mason|publisher=Brill Academic Publishers|year=1999}}</ref> Josephus was fluent in ], Hebrew and Greek. | |||

| ==The three passages== | |||

| ===James the brother of Jesus=== | |||

| ]]] | |||

| {{cquote2|And now Caesar, upon hearing the death of Festus, sent Albinus into Judea, as procurator. But the king deprived Joseph of the high priesthood, and bestowed the succession to that dignity on the son of Ananus, who was also himself called Ananus... Festus was now dead, and Albinus was but upon the road; so he assembled the sanhedrin of judges, and brought before them the brother of Jesus, who was called Christ, whose name was James, and some others; and when he had formed an accusation against them as breakers of the law, he delivered them to be stoned.<ref>Flavius Josephus: ''Antiquities of the Jews'' ] Text at ]</ref>}} | |||

| His writings are considered important secular historical documents that could, if genuine, shed light on the ].<ref name=FeldHata55 /><ref name=Maier285 /> Josephus' '']'', written around 93–94 AD, includes two references to Jesus in Books 18 and 20 and a reference to ] in Book 18.<ref name=FeldHata55 /><ref>''Josephus: The Essential Works'' by Flavius Josephus and Paul L. Maier 1995 ISBN 082543260X page 12</ref> Scholars are divided over the references, for example ] has noted that "the parallel sections of Josephus's '']'' make no mention of Jesus" <ref>L. Michael White, ''From Jesus To Christianity'', page 97 (HarperOne, 2005). ISBN 978-0-06-081610-0</ref> with ] making the same observation.<ref>Louis H. Feldman, Gōhei Hata, ''Josephus, The Bible, and History'', page 431 (E. J. Brill, Leiden, 1988). ISBN 90-04-08931-4. Quote: "We may add that the fact that in the passage in the ''War'' parallel to the one in the ''Antiquities'' about Pilate there is no mention of Jesus, despite the fact the account of Pilate in the ''War'' is almost as full as the version in the ''Antiquities'', corroborates our suspicion that there was either no passage about Jesus in the original text of the ''Antiquities'' or that it had a different form."</ref> A small number of critics believe the references involving James and John the Baptist passages could have been later Christian interpolations but the "overwhelming majority" of scholars consider they could be authentic.<ref name=FeldHata55 /><ref name=VVoorst83 /><ref name=Bauckham /><ref name=AmyJill55 /> The discovery of a Russian version of ''The Jewish War'' during the beginning of the twentieth century, commonly called the "Slavonic Josephus" or ''Testimonium Slavianum'',<ref name="Robert E. Van Voorst page 85">Robert E. Van Voorst, ''Jesus Outside The New Testament: An Introduction To The Ancient Evidence'', page 85 (Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2000). ISBN 0-8028-4368-9</ref> is cited as proof that the works of Josephus contained Christian interpolations.<ref name="Christians page 192">], ''The Jesus of the early Christians'', page 192 (Pemberton Books, 1971). ISBN 0301-71014-7</ref><ref name="Charles H. H 1964 pages 208-209">Charles H. H. Scobie, ''John the Baptist'' (SCM Press, 1964), reviewed in ''Journal of Biblical Literature'' by Charles E. Carlston (Volume 84, Number 2, June 1965, pages 208-209).</ref> The general scholarly view of the present day is that while the ''Testimonium Flavianum'' is most likely not authentic in its entirety, it originally consisted of an authentic nucleus with a reference to the execution of Jesus by Pilate which was then subject to interpolation.<ref name=Schubert38 /><ref name=Kellum104 /><ref name=Evans316/><ref name=Henry185/> Both Christian and Jewish scholars who propose this theory believe the ''Testimonium'' originally existed in a different form before being interpolated later by Christians, and restore what they believe was the original version of the passage, with the references to the miraculous material omitted. Each scholar presents his own differing restored version of the ''Testimonium''. These scholars include ], <ref>John P. Meier, ''A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus'', Volume 1, page 61 (Yale University Press, 2009). ISBN 978-0300140965 </ref> ], <ref>Shlomo Pines, ''An Arabic version of the Testimonium Flavianum and its implications'', pages 8-10, 16 (Jerusalem: Israel Academy of Arts and Humanities, 1971).</ref> ], <ref>Geza Vermes, "The Jesus Notice of Josephus Re-examined", in ''Journal of Jewish Studies'' (volume 38, issue 1, 1987).</ref> Paul Winter, <ref>Paul Winter, "Josephus on Jesus and James", in Emil Schürer, ''The History of the Jewish People in the Age of Jesus Christ (175 B.C.- A.D. 135)'', edited by Geza Vermes and Fergus Millar (Edinburgh: Clark, 1973; Excursus II, p. 437)</ref> ], <ref>James H. Charlesworth, ''Jesus within Judaism: New Light From Exciting Archaeological Discoveries'' (Doubleday, 1988)</ref> ], Frederick Fyvie Bruce, ''Jesus and Christian Origins Outside the New Testament'', page 39 (Eerdmans, 1974) and Claudia Setzer. <ref>Claudia Setzer, ''Jewish Responses to Early Christians: history and Polemics, 30-150 C.E''., pages 106–107 (Minneapolis: Fortress, 1994). ISBN 978-0800626808 </ref> | |||

| In the ] (]) Josephus refers to the stoning of "James the brother of Jesus" by order of ], a ] ] who died c. 68 AD.{{sfn|Harding|2003|p=317}}{{sfn|Painter|2005|pp=134-141}} The James referred to in this passage is most likely James the first bishop of Jerusalem who is also called ] in Christian literature, and to whom the ] has been attributed.{{sfn|Painter|2005|pp=134-141}}{{sfn|Freedman|Myers|Beck|2000|p=670}}{{sfn|Neale|2003|pp=2-3}} The translations of Josephus' writing into other languages have at times included passages that are not found in the Greek texts, raising the possibility of interpolation, but this passage on James is found in all manuscripts, including the Greek texts.{{sfn|Painter|2005|pp=134-141}} | |||

| ==Manuscripts== | |||

| None of the extant manuscripts of Josephus date from the early Christian period, and the first to witness any of the passages relating to Jesus was ], writing in about 324. The works of Josephus were translated into Latin during the fourth century (possibly by Rufinus), and during the same century the ''Jewish War'' was "partially rewritten as an anti-Jewish treatise, known today as ], but was considered for over a millenium and a half by many Christians as the '']'' of Josephus to his own people." <ref>Steven Bowman, "Jewish Responses to Byzantine Polemics from the Ninth through the Eleventh Centuries" , in Zev Garber (editor), ''The Jewish Jesus: Revelation, Reflection, Reclamation'', pages 186-187 (], 2011). ISBN 978-1-55753-579-5</ref> Variations in the Josephus manuscripts lasted for centuries - known to ], ] and the ], Suidas (flourished circa 1000 AD). During the seventeenth century it was "alleged that ] of Cambridge had large Greek fragments of Josephus not in the '']'': we do not know what became of them, and we are left to wonder whether their suppression was not deliberate." <ref>J. Spencer Kennard, Jr., "Gleanings from the Slavonic Josephus Controversy", '']'', (New Series, Volume 39, number 2, October 1948), page 164; with Kennard citing the article "Jean-Baptiste et Jésus suivant Josèphe" by ] referencing Thomas Gale in '']'', volume LXXXVII, n° 174 (avril-juin 1929); pages 113-136 . Reprinted in ''Amalthée: Mélanges d’Archéologie et d’Histoire'', Tome II (Paris: Libraire Ernest Leroux. 1930-1931), pages 314-342. </ref> | |||

| The earliest surviving Greek manuscript by Josephus is the Ambrosianus 370 (F 128), dating from the eleventh century, preserved in the ] in Milan. <ref>Steve Mason (editor), ''Flavius Josephus: Translation and Commentary'', Volume 9, ''Life of Josephus, Translation and Commentary by Steve Mason'', page LI, (Brill, Leiden; 2001). ISBN 90-04-11793-8</ref><ref></ref> | |||

| The context of the passage is the period following the death of ], and the journey to ] by ], the new ] ], who held that position from 62 AD to 64 AD.{{sfn|Painter|2005|pp=134-141}} Because the Albinus' journey to Alexandria had to have concluded no later than the summer of 62 AD, the date of James' death can be assigned with some certainty to around that year.{{sfn|Painter|2005|pp=134-141}}{{sfn|Mitchell|Young|2006|p=297}}{{sfn|Harding|2003|p=317}} The 2nd century chronicler ] also left an account of the death of James, and while the details he provides diverge from those of Josephus, the two accounts share similar elements.{{sfn|Painter|2004|p=126}}{{sfn|Bauckham|1999|pp=199-203}}{{sfn|Mitchell|Young|2006|p=297}} | |||

| ==James the brother of Jesus== | |||

| Modern scholarship overwhelmingly views the entire passage, including its reference to "the brother of Jesus called Christ", as authentic and has rejected its being the result of later interpolation.{{sfn|Van Voorst|2000|p=83}}<ref name=BauckhamA >] states that although a few scholars have questioned this passage, "the vast majority have considered it to be authentic" {{harv|Bauckham|1999|pp=199–203}}.</ref>{{sfn|Feldman|Hata|1987|pp=54-57}}{{sfn|Flavius Josephus|Maier|1995|pp=284-285}} Moreover, in comparison with Hegesippus' account of James' death, most scholars consider Josephus' to be the more historically reliable.{{sfn|Painter|2004|p=126}} However, a few scholars still question the authenticity of the reference, based on various arguments, but primarily based on the observation that various details in '']'' differ from it.{{sfn|Habermas|1996|pp=33-37}}{{sfn|Wells|1986|p=11}} | |||

| ]]] | |||

| In ''The Antiquities of the Jews'', Book XX, Chapter 9 of the ''Antiquities'' Josephus refers to the death of "the brother of Jesus, who was called Christ, whose name was James".<ref name=MHarding /><ref name=Painter134/> | |||

| {{cquote2|And now Caesar, upon hearing the death of Festus, sent Albinus into Judea, as procurator. But the king deprived Joseph of the high priesthood, and bestowed the succession to that dignity on the son of Ananus, who was also himself called Ananus... Festus was now dead, and Albinus was but upon the road; so he assembled the sanhedrin of judges, and brought before them the brother of Jesus, who was called Christ, whose name was James, and some others; and when he had formed an accusation against them as breakers of the law, he delivered them to be stoned.<ref>Josephus: The ''Antiquities of the Jews'' ] Text at ]</ref>}} | |||

| In the ] (]) Josephus refers to the stoning of "James the brother of Jesus" by order of ], a ] ] who died c. 68 AD.<ref name=MHarding >''Early Christian Life and Thought in Social Context'' by Mark Harding 2003 Sheffield Academic Press ISBN 0826456049 page 317</ref><ref name=Painter134/> The James referred to in this passage is thought to be the James the first bishop of Jerusalem who is also called ] in Christian literature, and to whom the ] has possibly been attributed.<ref name=Painter134>''Just James: The Brother of Jesus in History and Tradition'' by ] 2005 ISBN 0567041913 pages 134-141</ref><ref name=Eerdmans670 >''Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible'' 2000 ISBN 9053565035 page 670</ref><ref>''A History of the Holy Eastern Church'' by John Mason Neale 2003 ISBN 1593330456 pages 2-3</ref> The majority of today's scholars consider both the reference to "the brother of Jesus called Christ" and the entire passage that includes it as having the highest level of authenticity. <ref name=FeldHata55 /><ref name=Maier285 /><ref name=VVoorst83 /><ref name=Bauckham /> Sc the highest level of authenticity among the references of Josephus to Christianity.<ref name=FeldHata55 /> The translations of Josephus' writing into other languages have at times included passages that are not found in the Greek texts, raising the possibility of interpolation, but this passage on James is found in all manuscripts, including the Greek texts.<ref name=Painter134/> | |||

| ===John the Baptist=== | |||

| ] scolds ]. Fresco by ], 1435]]{{cquote2|Now some of the Jews thought that the destruction of Herod's army came from God, and that very justly, as a punishment of what he did against John, that was called the Baptist: for Herod slew him, who was a good man... Herod, who feared lest the great influence John had over the people might put it into his power and inclination to raise a rebellion... Accordingly he was sent a prisoner, out of Herod's suspicious temper, to Macherus, the castle I before mentioned, and was there put to death.<ref>Flavius Josephus: ''Antiquities of the Jews'' ] Text at ]</ref>}} | |||

| The word "Christ" is only found twice in the entire works of Josephus, both times in the alleged references to Jesus Christ found in ''Antiquities''. | |||

| In the '']'' (]) Josephus refers to the imprisonment and death of ] by order of ], the ruler of ] and ].{{sfn|Evans|2006|pp=55-58}}{{sfn|Bromiley|1982|pp=694-695}} The context of this reference is the 36 AD defeat of Herod Antipas in his conflict with ] of ], which the Jews of the time attributed to misfortune brought about by Herod's unjust ].{{sfn|White|2010|p=48}}{{sfn|Dapaah|2005|p=48}}{{sfn|Hoehner|1983|pp=125-127}} | |||

| Almost all modern scholars consider this passage to be authentic in its entirety, although a small number of authors have questioned it.{{sfn|Evans|2006|pp=55-58}}{{sfn|Flavius Josephus|Whiston|Maier|1999|pp=662-63}}{{sfn|Feldman|1992|pp=990-991}} Because the death of John also appears prominently in the Christian gospels, this passage is considered an important connection between the events Josephus recorded, the ] and the dates for the ].{{sfn|Evans|2006|pp=55-58}} A few scholars have questioned the passage, contending that the absence of Christian tampering or interpolation does not itself prove authenticity.{{sfn|Rothschild|2011|pp=257-258}} While this passage is the only reference to John the Baptist outside the New Testament, it is widely seen by most scholars as confirming the historicity of the baptisms that John performed.{{sfn|Evans|2006|pp=55-58}}{{sfn|Murphy|2003|p=2003}}{{sfn|Jonas|Lopez|2010|pp=95-96}}{{sfn|Chilton|Evans|1998|pp=187-198}} | |||

| James Carleton Paget has noted the passage about the death of James in Josephus "contrasts strongly with known Christian accounts of his death found for instance in Hegesippus, the ''Ascents of James'', Clement of Alexandria's ''Hypotyposeis'', and the ''Second Apocalypse of James''." <ref>James Carleton Paget, ''Jews, Christians and Jewish Christians in Antiquity'', page 192 (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2010). ISBN 978-3-16-150312-2</ref> | |||

| While both the gospels and Josephus refer to Herod Antipas killing John the Baptist, they differ on the details and the motive. While the gospels present this as a consequence of the marriage of Herod Antipas and ] in defiance of Jewish law (as in ], ]) Josephus refers to it as a pre-emptive measure by Herod to quell a possible uprising.{{sfn|Van Voorst|2003|pp=508-509}}{{sfn|Meyers|Craven|Kraemer|2001|pp=92-93}}{{sfn|Jensen|2010|pp=42-43}}{{sfn|White|2010|p=48}} | |||

| According to ] the overwhelming majority of today's scholars consider both the reference to "the brother of Jesus called Christ" and the entire passage that includes it as possibly authentic.<ref name=VVoorst83 >Jesus Outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence'' by Robert E. Van Voorst 2000 ISBN 0802843689 page 83</ref> ] states that although a few scholars have questioned this passage, "the vast majority have considered it to be authentic".<ref name=Bauckham >] "FOR WHAT OFFENSE WAS JAMES PUT TO DEATH?" in ''James the Just and Christian origins'' by Bruce Chilton, Craig A. Evans 1999 ISBN 9004115501 pages 199-203</ref> ] states that the possible authenticity of this Josephus passage has been "almost universally acknowledged".<ref name=FeldHata55 >''Josephus, Judaism and Christianity'' by ], Gōhei Hata 1997 ISBN 9004085548 pages 55-57</ref> ] states that most scholars agree with Feldman's assessment that "few have doubted the genuineness of this passage".<ref name=Maier285>''Josephus: The Essential Works'' by Flavius Josephus and Paul L. Maier 1995 ISBN 082543260X page 285</ref> | |||

| While Josephus identifies the location of the imprisonment of John as ], southeast of the mouth of the Jordan river, the gospels mention no location for the place where John was imprisoned.{{sfn|Freedman|Myers|Beck|2000|p=842}} However, according to other historical accounts Machaerus was rebuilt by ] around 30 AD and then passed to Herod Antipas.{{sfn|Freedman|Myers|Beck|2000|p=842}}{{sfn|Gillman|2003|pp=25-31}}{{sfn|Knoblet|2005|pp=15-17}} The 36 AD date of the conflict with Aretas IV mentioned by Josephus is, however, consistent (and shortly after) the approximate date of the marriage of ] and ] estimated by other historical methods.{{sfn|Gillman|2003|pp=25-31}}{{sfn|Hoehner|1983|p=131}}{{sfn|Bromiley|1982|pp=694-695}} | |||

| The context of this passage is the period after the death of ] and the journey to ] by ] the new ] ], who held that position from 62 AD to 64 AD.<ref name=Painter134 /> Because the journey of Albinus to Alexandria concluded at the latest in the summer of 62 AD, the date of the death of James can be assigned with some certainty to around that year.<ref name=MHarding /><ref name=Painter134/><ref name=MMM /> The death of James is also recorded by the 2nd century chronicler ] whose details diverge from those of Josephus, although the two accounts share similar elements.<ref name=Bauckham /><ref name=MMM >''The Cambridge History of Christianity, Volume 1: Origins to Constantine'' by Margaret M. Mitchell and Frances M. Young 2006 ISBN 0521812399 page 297</ref><ref name=Chilton120 /> Modern scholarship generally considers the description of the death of James given in Josephus to be possibly the most historically reliable account.<ref name=Bauckham /><ref name=Chilton120 >]: "Who was james?" in ''The brother of Jesus: James the Just and his mission'' by Bruce Chilton, Jacob Neusner 2004 ISBN 0814651526 pages 126</ref> | |||

| === Testimonium Flavianum === | |||

| ] | |||

| {{main|Authenticity of the Testimonium Flavianum}} | |||

| {{cquote2|Now there was about this time Jesus, a wise man, if it be lawful to call him a man; for he was a doer of wonderful works, a teacher of such men as receive the truth with pleasure. He drew over to him both many of the Jews and many of the Gentiles. He was ]. And when ], at the suggestion of the principal men amongst us, had condemned him to the ], those that loved him at the first did not forsake him; for he appeared to them alive again the third day; as the divine prophets had foretold these and ten thousand other wonderful things concerning him. And the tribe of Christians, so named from him, are not extinct at this day.<ref>Flavius Josephus: ''Antiquities of the Jews'', ] Text at ]</ref>}} | |||

| However, the above passage about Ananus from the ''Antiquities'' is directly contradicted by the equivalent account by Josephus of the character of Ananus as given in the ''Jewish Wars'', that does not mention the martyrdom of James and cites the death of Ananus as the reason for the beginning of the destruction of Jerusalem. From the surviving fragments of the Jewish Wars: "I should not be wrong in saying, that with the death of Ananus began the capture of the city, and from that very day on which the Jews beheld their high priest and the guardians of their safety, murdered in the midst of Jerusalem, its bulwarks were laid low, and the Jewish state overthrown." <ref>''The Jewish War of Flavius Josephus: A New Translation'' Book IV. (Boston: John P. Jewett and Company, 1858). Available from Google Books </ref><ref>Clemens Thoma, "The High Priesthood in the Judgment of Josephus", in Louis H. Feldman, Gōhei Hata (editors), ''Josephus, The Bible, And History'', pages 212-213 (E. J. Brill, Leiden; 1988). ISBN 90-04-08931-4</ref> | |||

| The ''Testimonium Flavianum'' (meaning the testimony of Flavius <nowiki></nowiki>) is the name given to the passage found in ] of the Antiquities in which Josephus describes the condemnation and crucifixion of Jesus at the hands of the Roman authorities.{{sfn|Flavius Josephus|Whiston|Maier|1999|p=662}}{{sfn|Schreckenberg|Schubert|1992a|pp=38-41}} The ''Testimonium'' is likely the most discussed passage in Josephus and perhaps in all ancient literature.{{sfn|Feldman|Hata|1987|pp=54-57}} | |||

| Since the 19th century, a small number of authors have questioned the authenticity of this Josephus passage, generally in the context of the denial of the existence of Jesus, the inaccuracy of the Christian gospels, or that in '']'' Josephus does not mention this incident.<ref name=Habermas33 >''The Historical Jesus'' by Gary R. Habermas 1996 ISBN 0899007325 pages 33-37</ref><ref name= Houlden660 /> Going back to ] in the 19th century these authors have included ] and ] and their views culminated in the writings of ] who in 1986 argued that the passage was interpolated by Christian authors within the context that Jesus never existed.<ref name=Habermas33/><ref>George Albert Wells, '']'', (1986) Pemberton Publishing Co., p. 11</ref><ref>], 1985 ''The Evidence for Jesus'' ISBN 0664246982 page 29</ref> However, this has been an ongoing debate and towards the end of the 20th century Wells changed his views and accepted the possible existence of Jesus, although still disputing Christian sources.<ref name= Houlden660 >''Jesus in history, thought, and culture: an encyclopedia, Volume 1'' by James Leslie Houlden 2003 ISBN 1576078566 page 660</ref><ref>''Familiar stranger: an introduction to Jesus of Nazareth'' by Michael James McClymond 2004 ISBN 0802826806 page 163</ref><ref>G.A. Wells, ''The Jesus Myth'', Open Court 1999, ISBN 0812693922</ref><ref name=VVoorst14 >Jesus Outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence'' by Robert E. Van Voorst 2000 ISBN 0802843689 page 14</ref> | |||

| The earliest secure reference to this passage is found in the writings of the fourth-century Christian apologist and historian ], who used Josephus' works extensively as a source for his own ]. Writing no later than 324,{{sfn|Louth|1990|}} Eusebius quotes the passage{{sfn|McGiffert|2007}} in essentially the same form as that preserved in extant manuscripts. It has therefore been suggested that part or all of the passage may have been Eusebius' own invention, in order to provide an outside Jewish authority for the life of Christ.{{sfn|Olson|1999}}{{sfn|Wallace-Hadrill|2011}} However, it is also possible that others, including the third-century ] writer ] also knew of the passage. Although Origen makes no direct reference to the ''Testimonium'', scholars such as Louis Feldman and Zvi Baras have presented arguments that Origen may have seen a copy of the Testimonium and not commented on it for there was no need to complain about its tone.{{sfn|Feldman|1984|p=823}}{{sfn|Baras|1987|pp=340-341}} | |||

| Claudia Setzer has noted that "what is striking is that Ananus accuses James of transgressing the ], but in the New Testament James appears as an advocate of loyalty to the Torah (]. 2:12, ] 21:20-24)." <ref>Claudia Setzer, "Jewish Responses to Believers in Jesus", in Amy-Jill Levine, Marc Z. Brettler (editors), ''The Jewish Annotated New Testament'', page 577 (New Revised Standard Version, Oxford University Press, 2011). ISBN 978-0195297706</ref> | |||

| Of the three passages found in Josephus' Antiquities, this passage, if authentic, would offer the most direct support for the crucifixion of Jesus. The general scholarly view is that while the Testimonium Flavianum is most likely not authentic in its entirety, it originally consisted of an authentic nucleus with a reference to the execution of Jesus by Pilate which was then subject to interpolation.{{sfn|Schreckenberg|Schubert|1992a|pp=38-41}}{{sfn|Kostenberger|Kellum|Quarles|2009|pp=104-108}}{{sfn|Evans|2001|p=316}}{{sfn|Wansbrough|2004|p=185}} ] states that there is "broad consensus" among scholars regarding the nature of an authentic reference to Jesus in the ''Testimonium'' and what the passage would look like without the interpolations.{{sfn|Dunn|2003|p=141}} Among other things, the authenticity of this passage would help make sense of the later reference in Josephus ] ] where Josephus refers to the stoning of "James the brother of Jesus". A number of scholars argue that the reference to Jesus in this later passage as "the aforementioned Christ" relates to the earlier reference in the ''Testimonium''.{{sfn|Feldman|Hata|1987|pp=54-57}}{{sfn|Flavius Josephus|Maier|1995|pp=284-285}}{{sfn|Vermes|2011|pp=33-44}} | |||

| Scholars who have doubted the authenticity of the passage about James in Josephus include Tessa Rajak (1983) and Ken Olson (1999). <ref>James Carleton Paget, ''Jews, Christians and Jewish Christians in Antiquity'', page 192, footnote 28 (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2010). ISBN 978-3-16-150312-2</ref> | |||

| ==Ancient and medieval sources== | |||

| ===Extant manuscripts=== | |||

| ] | |||

| Josephus wrote all of his surviving works after his establishment in Rome (c. AD 71) under the patronage of the Flavian Emperor ]. As is common with ancient texts, however, there are no surviving extant manuscripts of Josephus' works that can be dated before the 11th century, and the oldest of these are all Greek minuscules, copied by Christian monks.{{sfn|Feldman|Hata|1989|p=431}} (Jews did not preserve the writings of Josephus because they considered him to be a traitor.{{sfn|Flavius Josephus|Leeming|Osinkina|Leeming|2003|p=26}}) | |||

| Carl Clemen commented on the unreliabilty of the passage about James: "especially because Origen, who three times mentions Josephus' account of the death of James, read it differently". <ref>Carl Clemen, "Josephus and Christianity", page 366. ''The Biblical World'', Volume 25, Number 5 (May, 1905).</ref> ] has also commented: "That there has been some tampering with that passage is suggested by the fact that Origen, who refers to Josephus's account of the death of James, claims to have read something rather different on that subject in his text of Josephus from what now stands there." <ref>G. A. Wells, ''The Jesus Legend'', page 54 (Carus Publishing Company, 1997). ISBN 0-8126-9334-5</ref> | |||

| There are about 120 extant Greek manuscripts of Josephus, of which 33 predate the 14th century, with two thirds from the ] period.{{sfn|Baras|1987|p=369}} The earliest surviving Greek manuscript that contains the ''Testimonium'' is the 11th century Ambrosianus 370 (F 128), preserved in the ] in Milan, which includes almost all of the second half of the ''Antiquities''. {{sfn|Mason|2001|p=LI}} There are about 170 extant Latin translations of Josephus, some of which go back to the sixth century, and according to ] have proven very useful in reconstructing the Josephus texts through comparisons with the Greek manuscripts, reconfirming proper names and filling in gaps.{{sfn|Feldman|1984}} | |||

| ==John the Baptist== | |||

| There is considerable evidence, however, that attests to the existence of the references to Jesus in Josephus well before then, including a number of ''ad hoc'' copies of Josephus' work preserved in quotation from the works of Christian writers. The earliest known such reference to Josephus' work is found in the writings of the third century patristic author ], although he does not provide any direct reference to the passages involving Jesus. The first witness to any of the passages relating to Jesus was ], writing in the first decades of the fourth century.{{sfn|Louth|1990|}} Both Origen and Eusebius had access to the Greek versions of Josephus' texts. The works of Josephus were translated into Latin during the fourth century (possibly by ]), and, in the same century, the ''Jewish War'' was "partially rewritten as an anti-Jewish treatise, known today as ], but <nowiki></nowiki> was considered for over a millenium and a half by many Christians as the '']'' of Josephus to his own people." {{sfn|Bowman|2011|pp=186-187}} | |||

| ] scolds ]. Fresco by ], 1435]]{{cquote2|Now some of the Jews thought that the destruction of Herod's army came from God, and that very justly, as a punishment of what he did against John, that was called the Baptist: for Herod slew him, who was a good man... Herod, who feared lest the great influence John had over the people might put it into his power and inclination to raise a rebellion... Accordingly he was sent a prisoner, out of Herod's suspicious temper, to Macherus, the castle I before mentioned, and was there put to death.<ref>Josephus: ''Antiquities of the Jews'' ] Text at ]</ref>}} | |||

| In the '']'' (]) Josephus refers to the imprisonment (and death) of ] by order of ], the ruler of ] and ].<ref name=AmyJill55 /><ref name=Bromiley694 >''International Standard Bible Encyclopedia: E-J'' by Geoffrey W. Bromiley 1982 ISBN 0802837824 pages 694-695</ref> The context of this reference is the 36 AD defeat of Herod Antipas in his conflict with ] of ], which the Jews of the time attributed to misfortune brought about by Herod's unjust ].<ref name=Cyndy48 /><ref>''The relationship between John the Baptist and Jesus of Nazareth'' by Daniel S. Dapaah 2005 ISBN 0761831096 page 48</ref><ref name=Hoehner125 >''Herod Antipas'' by Harold W. Hoehner'' 1983 ISBN 0310422515 pages 125-127</ref> Almost all modern scholars strongly consider this Josephus passage about John to be possibly authentic in its entirety.<ref name=AmyJill55 /><ref name="Louis H. Feldman pp. 990-1">Louis H. Feldman, "Josephus" Anchor Bible Dictionary, Vol. 3, pp. 990-1.</ref> Given that the death of John also appears in the Christian gospels, this passage is considered an important connection between the events Josephus recorded, the ] and the dates for the ].<ref name=AmyJill55 /> | |||

| One of the reasons the works of Josephus were copied and maintained by Christians was that his writings provided a good deal of information about a number of figures mentioned in the New Testamant, and the background to events such as the death of James during a gap in Roman governing authority.{{sfn|Van Voorst|2000|p=83}} Because manuscript transmission was done by hand-copying, typically by monastic scribes, almost all ancient texts have been subject to both accidental and deliberate alterations, emendations (called ]) or elisions. It is both the lack of any original corroborating manuscript source outside the Christian tradition as well as the practice of Christian interpolation that has led to the scholarly debate regarding the authenticity of Josephus' references to Jesus in his work. Although there is no doubt that most (but not all<ref>For example, an ancient Table of Contents of the eighteenth book of the ''Antiquities'' omits any reference to the passage about Jesus, as does the Josephus codex of the patriarch ]. Nor is it clear if the ''Testimonium'' existed in the Josephus exemplar used by ]. See {{harvnb|Schreckenberg|Schubert|1992b|pp=57–58}}.</ref>) of the later copies of the ''Antiquities'' contained references to Jesus and John the Baptist, it cannot be definitively shown that these were original to Josephus writings, and were not instead added later by Christian interpolators. Much of the scholarly work concerning the references to Jesus in Josephus has thus concentrated on close textual analysis of the Josephan corpus to determine the degree to which the language, as preserved in both early Christian quotations and the later transmissions, should be considered authentic. | |||

| If authentic, the passage represents the only corroboration of his life outside of early Christian literature. Clare K. Rothschild has noted that "Today we have only three Greek manuscripts of this portion of the ''Antiquities'', the earliest of which dates to the eleventh century" and "absence of Christian tampering does not constitute positive proof of authenticity", also observing "arguments both for and against authenticity of the passage have advantages and flaws of equal weight making a clear decision either way impossible." <ref>Clare K. Rothschild, "Echo of a Whisper": The Uncertain Authenticity of Josephus' Witness to John the Baptist, in David Hellholm, Tor Vegge, A~yvind Norderval, Christer Hellholm (editors), ''Ablution, Initiation, and Baptism: Late Antiquity, Early Judaism, and Early Christianity'', pages 257 and 258 (Walter de Gruyter, 2011). ISBN 978-3-11-024751-0</ref> | |||

| ====Slavonic Josephus==== | |||

| {{main|Slavonic Josephus}} | |||

| The three references found in ] and | |||

| ] of the ''Antiquities'' do not appear in any other versions of Josephus' '']'' except for a ] version of the ''Testimonium Flavomium'' (at times called ''Testimonium Slavonium'') which surfaced in the west at the beginning of the 20th century, after its discovery in Russia at the end of the 19th century.{{sfn|Van Voorst|2000|p=85}}{{sfn|Creed|1932}} | |||

| Although originally hailed as authentic (notably by ]), it is now almost universally acknowledged by scholars to have been the product of an 11th century creation as part of a larger ideological struggle against the ].{{sfn|Bowman|1987|pp=373-374}} As a result, it has little place in the ongoing debate over the authenticity and nature of the references to Jesus in the ''Antiquities.''{{sfn|Bowman|1987|pp=373-374}} ] states that although some scholars had in the past supported the ''Slavonic Josephus'', "to my knowledge no one today believes that they contain anything of value for Jesus research".{{sfn|Chilton|Evans|1998|p=451}} | |||

| ====Arabic and Syriac Josephus==== | |||

| In 1971, a 10th century Arabic version of the ''Testimonium'' due to ] was brought to light by ] who also discovered a 12th century ] version of Josephus by ].{{sfn|Pines|1971|p=19}}{{sfn|Maier|2007|pp=336-337}}{{sfn|Feldman|2006|pp=329-330}} These additional manuscript sources of the Testimonium have furnished additional ways to evaluate Josephus' mention of Jesus in the ''Antiquities'', principally through a close textual comparison between the Arabic, Syriac and Greek versions to the ''Testimonium''.{{sfn|Kostenberger|Kellum|Quarles|2009|pp=104-108}}{{sfn|Van Voorst|2000|p=97}} | |||

| There are subtle yet key differences between the Greek manuscripts and these texts. For instance, the Arabic version does not blame the Jews for the death of Jesus. The key phrase "at the suggestion of the principal men among us" reads instead "Pilate condemned him to be crucified".<ref>''The historical Jesus: ancient evidence for the life of Christ'' by Gary R. Habermas 1996 ISBN page 194</ref>{{sfn|Kostenberger|Kellum|Quarles|2009|pp=104-108}} And instead of "he was Christ," the Syriac version has the phrase "he was believed to be Christ".{{sfn|Vermes|2011|33-44}} Drawing on these textual variations, scholars have suggested that these versions of the ''Testimonium'' more closely reflect what a non-Christian Jew may have written. {{sfn|Maier|2007|pp=336-337}} | |||

| ===Early References=== | |||

| ]]] | |||

| In the 3rd century, ] was the first ancient writer to have a comprehensive reference to Josephus, although some other authors had made smaller, general references to Josephus before then, e.g. ] and ] in the second century, followed by ].{{sfn|Mizugaki|1987}}{{sfn|Flavius Josephus|Whiston|Maier|1999|p=15}} Origen explicitly mentions the name of Josephus 11 times, both in Greek and Latin. However, despite the fact that most of Origen's works only survive in Latin translations, 10 out of the 11 references are in the original Greek.{{sfn|Mizugaki|1987}} | |||

| The context for Origen's references is his defense of Christianity.{{sfn|Mizugaki|1987}} In '']'' (]) as Origen defends the Christian practice of ], he recounts Josephus' reference to the baptisms performed by ] for the sake of purification.{{sfn|Mizugaki|1987}} In ] Origen mentions Josephus' reference to the death of ]. And again in his ''Commentary on Matthew'' (]) Origen refers to Josephus' ''Antiquities of the Jews'' by name and that Josephus had stated that the death of James had brought a wrath upon those who had killed him.{{sfn|Mizugaki|1987}}{{sfn|Painter|2005|p=205}} | |||

| The 4th century writings of ] refer to Josephus' account of James, John and Jesus. In his '']'' (]) Eusebius discusses the Josephus reference to how ] killed ], and mentions the marriage to ] in items 1 to 6. In the same Book I chapter, in items 7 and 8 Eusebius also discusses the Josephus reference to the crucifixion of Jesus by ], a reference that is present in all surviving Eusebius manuscripts.{{sfn|Maier|2007|pp=336-337}}{{sfn|Bartlett|1985|pp=92-94}} | |||

| In ] of his ''Church History'', Eusebius describes the death of James according to Josephus. In that chapter, Eusebius first describes the background including ], and mentions ] and ]. In item 20 of that chapter Eusebius then mentions Josephus' reference to the death of James and the sufferings that befell those who killed him. However, Eusebius does not acknowledge Origen as one of his sources for the reference to James in Josephus.{{sfn|Painter|2005|pp=155-167}} | |||

| ==Detailed Analysis== | |||

| ===Variations from Christian sources=== | |||

| There are some variations between the statements by Josephus regarding James the brother of Jesus and John the Baptist and the ] and other Christian accounts. Scholars generally view these variations as indications that the Josephus passages are not interpolations, for a Christian interpolator would have made them correspond to the Christian traditions.{{sfn|Evans|2006|pp=55-58}}{{sfn|Eddy|Boyd|2007|p=130}} | |||

| Josephus' account places the date of the death of James as AD 62.<ref>''International Standard Bible Encyclopedia: A-D'' by Geoffrey W. Bromiley 1979 ISBN 0-8028-3781-6 page 692</ref> This date is supported by ]'s 'seventh year of the Emperor Nero', although Jerome may simply be drawing this from Josephus.{{sfn|Painter|2005|pp=221–222}} However, James' successor as leader of the Jerusalem church, ], is not, in tradition, appointed till after the ] in AD 70, and Eusebius' notice of Simeon implies a date for the death of James immediately before the siege, i.e. about AD 69.{{sfn|Painter|2005|pp=143–145}} The method of death of James is not mentioned in the New Testament.<ref>''The Bible Exposition Commentary: New Testament'' by Warren W. Wiersbe 2003 ISBN 1564760316 page 334</ref> However, the account of Josephus differs from that of later works by Hegesippus, Clement of Alexandria, and Origen, and Eusebius of Caesarea that it simply has James stoned while the others have other variations such as having James thrown from the top of the Temple, stoned, and finally beaten to death by laundrymen{{sfn|Eddy|Boyd|2007|p=189}} as well as his death occurring during the siege of Jerusalem in AD 69. | |||

| ] from the ], 1493]] | |||

| ] states that the relationship of the death of James to the siege is an important theologoumenon in the early church.{{sfn|Painter|2005|pp=143–145}} On the basis of the Gospel accounts it was concluded that the fate of the city was determined by the death there of Jesus.{{sfn|Painter|2005|pp=143–145}} To account for the 35 year difference, Painter states that the city was preserved temporarily by the presence within it of a 'just man' (see also ]); who was identified with James, as confirmed by Origen. Hence Painter states that the killing of James restarted the clock that led to the destruction of the city and that the traditional dating of 69 AD simply arose from an over-literal application of the theologoumenon, and is not to be regarded as founded on a historical source.{{sfn|Painter|2005|pp=143–145}} The difference between Josephus and the Christian accounts of the death of James is seen as an indication that the Josephus passage is not a Christian interpolation by scholars such as Eddy, Boyd, and Kostenberger.{{sfn|Eddy|Boyd|2007|p=189}}{{sfn|Kostenberger|Kellum|Quarles|2009|pp=104-05}} ] states that compared to the Christian accounts: "the sober picture of Josephus appears all the more believable".<ref>Vermes, Geza (2011). ''Jesus in the Jewish World''. ISBN 0-334-04379-4 page 40</ref> ], on the other hand, has stated that in view or ]'s statements these variations from the Christian accounts may be signs of interpolation in the James passage.<ref name=Wells545 /> | |||

| The marriage of ] and ] is mentioned both in Josephus and in the gospels, and scholars consider Josephus as a key connection in establishing the approximate chronology of specific episodes related to John the Baptist.{{sfn|Evans|2006|pp=55-58}} However, although both the gospels and Josephus refer to Herod Antipas killing John the Baptist, they differ on the details and motives, e.g. whether this act was a consequence of the marriage of Herod Antipas and Herodias (as indicated in ], ]), or a pre-emptive measure by Herod which possibly took place before the marriage to quell a possible uprising based on the remarks of John, as Josephus suggests in ].{{sfn|Van Voorst|2003|pp=508-509}}<ref name=Cyndy48 >''The Emergence of Christianity: Classical Traditions in Contemporary Perspective'' by Cynthia White 2010 ISBN 0-8006-9747-2 page 48</ref>{{sfn|Gillman|2003|pp=25-31}} | |||

| ] has stated that there is "no necessary contradiction between Josephus and the gospels as to the reason why John was put to death" in that the Christians chose to emphasize the moral charges while Josephus emphasized the political fears that John stirred in Herod.<ref>''Josephus and Modern Scholarship'' by Louis H. Feldman 1984, ISBN 3-11-008138-5 page 675</ref> | |||

| Josephus stated (]) that the AD 36 defeat of Herod Antipas in the conflicts with ] of ] was widely considered by the Jews of the time as misfortune brought about by Herod's unjust execution of John the Baptist.<ref name=Cyndy48 /><ref>''The relationship between John the Baptist and Jesus of Nazareth'' by Daniel S. Dapaah 2005 ISBN 0-7618-3109-6 page 48</ref><ref name=Hoehner125 >''Herod Antipas'' by Harold W. Hoehner'' 1983 ISBN 0-310-42251-5 pages 125-127</ref> The approximate dates presented by Josephus are in concordance with other historical records, and most scholars view the variation between the motive presented by Josephus and the New Testament accounts is seen as an indication that the Josephus passage is not a Christian interpolation.{{sfn|Evans|2006|pp=55-58}} | |||

| ===Arguments challenging authenticity=== | |||

| ====The James passage==== | |||

| ]'']] | |||

| A comparative argument made against the authenticity of the James passage by scholars such as Tessa Rajak is that the passage has a negative tone regarding the High Priest ], presenting him as impulsive while in the Jewish Wars Josephus presents a positive view of Ananus and portrays him as prudent.{{sfn|Eddy|Boyd|2007|pp=128-130}} {{sfn|Feldman|Hata|1987|p=56}} | |||

| A textual argument against the authenticity of the James passage is that the use of the term "Christos" there seems unusual for Josephus.{{sfn|Eddy|Boyd|2007|pp=128-130}} An argument based on the flow of the text in the document is that given that the mention of Jesus appears in the ''Antiquities'' before that of the John the Baptist a Christian interpolator may have inserted it to place Jesus in the text before John.{{sfn|Eddy|Boyd|2007|pp=128-130}} A further argument against the authenticity of the James passage is that it would have read well even without a reference to Jesus.{{sfn|Eddy|Boyd|2007|pp=128-130}} | |||

| Although a small number of authors have questioned this reference, <ref>For example, Léon Herrmann, ''Chrestos, Témoignages païens et juifs sur le christianisme: du premier siècle,'' (Bruxelles, Latomus, 1970).</ref> almost all modern scholars consider this Josephus passage about John to be possibly authentic in its entirety.<ref name=AmyJill55 >Craig Evans, 2006 "Josephus on John the Baptist" in ''The Historical Jesus in Context'' edited by Amy-Jill Levine et al. Princeton Univ Press ISBN 9780691009926 pages 55-58</ref><ref name="Louis H. Feldman pp. 990-1"/><ref>''The new complete works of Josephus by Flavius Josephus'', William Whiston, Paul L. Maier ISBN 0825429242 pages 662-663</ref> Given that the death of John also appears in the Christian gospels, this passage is considered an important connection between the events Josephus recorded, the ] and the dates for the ].<ref name=AmyJill55 /> | |||

| Some of the arguments for and against the authenticity of the James passage revolve around the similarities and differences between the accounts of Josephus, Origen, Eusebius and the New testament. Although Josephus' account of the method of death of James differs from that of the New Testament, this is seen as an indication that the Josephus account is not a Christian interpolation.{{sfn|Eddy|Boyd|2007|p=130}} | |||

| While both the gospels and Josephus refer to Herod Antipas killing John the Baptist, they differ on the details and the motive. While the gospels present this as a consequence of the marriage of Herod Antipas and ] in defiance of Jewish law (as in ], ]) Josephus refers to it as a pre-emptive measure by Herod to quell a possible uprising.<ref name=Cyndy48 >''The Emergence of Christianity: Classical Traditions in Contemporary Perspective'' by Cynthia White 2010 ISBN 0800697472 page 48</ref><ref name=Leslie508 >''Jesus in history, thought, and culture: an encyclopedia, Volume 1'' by James Leslie Houlden 2003 ISBN 1576078566 pages 508-509</ref><ref>''Women in scripture'' by by Carol Meyers, Toni Craven and Ross Shepard Kraemer 2001 ISBN 0802849628 pages 92-93</ref><ref>''Herod Antipas in Galilee: The Literary and Archaeological Sources'' by Morten H. Jensen 2010 ISBN 978-3-16-150362-7 pages 42-43</ref> However, this difference between the motive presented in the gospels and the one stated by Josephus is one of several criteria scholars list in favor of the possible authenticity of the Josephus passage, given that Christian interpolators would have most probably made it consistent with the gospels.<ref name=Feldman331 >''Judaism and Hellenism reconsidered'' by Louis H. Feldman 2006 ISBN 9004149066 pages 330-331</ref> Feldman also states that Christian interpolators would have been very unlikely to have devoted almost twice as much space to John (163 words) as to Jesus (89 words).<ref name=Feldman331 /> | |||

| John Painter states that Origen expresses surprise that given that a Josephus who disbelieves in Jesus as Christ (''Commentary on Matthew'' ]) should write respectfully of James, his brother.{{sfn|Painter|2005|pp=132-137}} However, according to Painter unlike the ''Testimonium'' this issue has not generated a great deal controversy, although viewed as a potential reason for doubting authenticity.{{sfn|Painter|2005|pp=132-137}} | |||

| While Josephus identifies the location of the imprisonment of John as ], southeast of the mouth of the Jordan river, the gospels mention no location for the place where John was imprisoned.<ref name=Machaerus >''Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible'' 2000 ISBN 9053565035 page 842</ref> However, according to other historical accounts Machaerus was rebuilt by ] around 30 AD and then passed to Herod Antipas.<ref name=Machaerus /><ref name=fox25 /><ref>''Herod the Great'' by Jerry Knoblet 2005 ISBN 0761830871 pages 15-17</ref> The 36 AD date of the conflict with Aretas IV mentioned by Josephus is, however, consistent (and shortly after) the approximate date of the marriage of ] and ] estimated by other historical methods.<ref name=Bromiley694 /><ref name=fox25 >''Herodias: at home in that fox's den'' by Florence Morgan Gillman 2003 ISBN 0814651089 pages 25-31</ref><ref>''Herod Antipas'' by Harold W. Hoehner'' 1983 ISBN 0310422515 page 131]</ref> | |||

| An issue that is subject to more debate is that in ''Commentary on Matthew'' (]), Origen cites Josephus as stating the death of James had brought a wrath upon those who had killed him, and that his death was the cause of the destruction of Jerusalem.{{sfn|Mizugaki|1987}}{{sfn|Painter|2005|p=205}}<ref>Quoting Mizugaki, page 335: "Origen notes with favour that Josephus seeks the cause of the fall of Jerusalem and the destruction of the Temple in the assassination of James the Just but gravely adds that Josephus ought to have stated that the calamity happened because the Jews killed Christ."</ref> A the end of ] Origen disagrees with Josephus' placement of blame for the destruction of Jerusalem on the death of James, and states that it was due to the death of Jesus, not James.{{sfn|Painter|2005|pp=132-137}} | |||

| The differences between the two accounts of John the Baptist found in Josephus and the New Testament have been noted by Claudia Setzer. In Mark it is the daughter of Herodias who instigates the execution of John the Baptist; while John the Baptist in the New Testament preaches a "baptism of repentance for the forgiveness of sins" (Mark 1:4), Josephus describes he rejected that interpretation ("For immersion in water, it was clear to him, could not be used for the forgiveness of sins"); and Josephus wrote he was "executed out of fear that he may be a revolutionary, a motif that is absent from the New Testament." <ref>Claudia Setzer, "Jewish Responses to Believers in Jesus", in Amy-Jill Levine, Marc Z. Brettler (editors), ''The Jewish Annotated New Testament'', page 576 (New Revised Standard Version, Oxford University Press, 2011). ISBN 978-0195297706 </ref> | |||

| In ] of his ''Church History'', Eusebius mentions Josephus' reference to the death of James and the sufferings that befell those who killed him. In this reference Eusebius writes: “These things happened to the Jews to avenge James the Just, who was a brother of Jesus, that is called the Christ. For the Jews slew him, although he was a most just man.” However, this statement does not appear in the extant manuscripts of Josephus.{{sfn|Painter|2005|pp=132-137}} Painter states that whether the Book II, Chapter 23.20 statement by Eusebius is an interpolation remains an open question.{{sfn|Painter|2005|pp=132-137}} | |||

| ==Testimonium Flavianum== | |||

| Eusebius does not acknowledge Origen as one of his sources for the reference to James in Josephus.{{sfn|Painter|2005|pp=155-167}} However, John painter states that placing the blame for the siege of Jerusalem on the death of James is perhaps an early Christian invention that predates both Origen and Eusebius and that it likely existed in the traditions to which they were both exposed.{{sfn|Painter|2005|pp=132-137}} Painter states that it is likely that Eusebius may have obtained his explanation of the siege of Jerusalem from Origen.{{sfn|Painter|2005|pp=155-167}} | |||

| Book 18 of Josephus' ''Antiquities of the Jews'' contains the following disputed passage about Jesus Christ: | |||

| ] has stated that the fact that Origen seems to have read something different about the death of James in Josephus than what there is now, suggests some tampering with the James passage seen by Origen.<ref name=Wells545>''The Jesus Legend'' by G. A. Wells 1996 ISBN 0-8126-9334-5 pages 54-55</ref> Wells suggests that the interpolation seen by Origen may not have survived in the extant Josephus manuscripts, but that it opens the possibility that there may have been other interpolations in Josephus' writings.<ref name=Wells545 /> Wells further states that differences between the Josephus account and those of ] and ] may point to interpolations in the James passage.<ref name=Wells545 /> | |||

| ] | |||

| {{cquote2|Now there was about this time Jesus, a wise man, if it be lawful to call him a man; for he was a doer of wonderful works, a teacher of such men as receive the truth with pleasure. He drew over to him both many of the Jews and many of the Gentiles. He was ]. And when ], at the suggestion of the principal men amongst us, had condemned him to the ], those that loved him at the first did not forsake him; for he appeared to them alive again the third day; as the divine prophets had foretold these and ten thousand other wonderful things concerning him. And the tribe of Christians, so named from him, are not extinct at this day.<ref>Josephus: ''Antiquities of the Jews'', ] Text at ]</ref>}} | |||

| Paul L. Maier, former ] of ] at ] stated scholars fall into three main camps over its authenticity: 1) It is entirely authentic, 2) It is entirely a Christian forgery and 3) It contains Christian interpolations in what was Josephus's authentic material about Jesus.<ref>Paul L. Maier, ''The New Complete Works of Josephus'', page 662 (Kregel Publications, 1999). ISBN 0-8254-2924-2</ref><ref>Paul L. Maier, ''Eusebius: The Church History'', page 336 (Kregel Publications, 2007). ISBN 978-0-8254-3307-8</ref> | |||

| An argument going back to at least 1893 against the authenticity of the reference in the James passage is that the "Jesus son of Damneus" at the end of the passage was the Jesus actually being refereed to by Josephus and the "who was called Christ" as a later interpolation usually along the lines of a added (and mistaken about who this Jesus was) ] that was later incorporated into the text proper.<ref>Mitchell, Richard M. (1893) ''The Safe Side: A Theistic Refutation of the Divinity of Christ'' pg 188-189</ref> Drews in ''The Witness To The Historicity of Jesus'' pointed out even if the passage was entirely genuine the term "brother" could have been used in a spiritual sense and that all the passage really shows is a James belonging to a sect that venerated a Messiah called Jesus.<ref>Arthur Drews, ''The Witness To The Historicity of Jesus'', page 9 (London: Watts & Co., 1912). </ref> Recent amateur research has built on the acknowledgement that "christ" was a term meaning "annotated one" as well a title referring to Jesus proper and that high priests per Exodus 29:9 and 1 Samuel 10:1 were "annotated"<ref name=Mason228 >Mason, Steve (2002) ''Josephus and the New Testament'' Baker Academic ISBN 978-0-8010-4700-8 page 228</ref>, suggesting that since "Jesus son of Damneus" would have been literally become the "annotated one" (ie 'christ' with a little 'c') upon becoming high priest that there is nothing to suggest thar he and the "Jesus who was called Christ" are two separate people other then the wishful thinking of apologists especially in the light of the fact the majority of sources and early Christianity tradition put James dying c70 CE by being thrown from a battlement, stoned, and finally clubbed to death by passing laundrymen.<ref>Eddy, Paul R. and Boyd, Gregory A. (2007) ''The Jesus Legend: A Case for the Historical Reliability of the Synoptic Jesus Tradition''. Baker Academic, pg 189</ref> | |||

| In ] of the ''Antiquities'' Josephus refers to the execution of Jesus by ].<ref name=FeldHata55 /><ref name=Schubert38 /> This passage is generally called the '']''. It is the most discussed passage in all of Josephus' writings and perhaps in all ancient literature.<ref name=FeldHata55 /> Scholars have differing views on the authenticity of the ''Testimonium''. The general scholarly view is that while the ''Testimonium Flavianum'' is most likely not authentic in its entirety, it originally consisted of an authentic nucleus with a reference to the execution of Jesus by Pilate which was then subject to interpolation.<ref name=Schubert38 /><ref name=Kellum104 /><ref name=Evans316/><ref name=Henry185/> However, ] has cautiously stated that "nothing is certain" (see below). <ref>James Leslie Houlden, ''Jesus in History, Thought, and Culture: An Encyclopedia. Entries A - J'', Volume 1, page 510 (ABC-CLIO, Inc., 2003). ISBN 1-57607-856-6</ref> A number of scholars suggest a relationship between the ''Testimonium'' and the reference to James the brother of Jesus, viewing the ''Testimonium'' as the initial reference to Jesus, which is then referred to again in the passage on James in Book 20.<ref name=FeldHata55 /><ref name=Maier285 /><ref name=Geza40/> | |||

| ====John the Baptist==== | |||

| Scholars such as Claudia Setzer have noted the differences between the rationale for the death of John the Baptist presented by Josephus, and the theological variations (e.g. whether immersion in water can result in the forgiveness of sins, etc.) and the New Testament accounts.<ref>Claudia Setzer, "Jewish Responses to Believers in Jesus", in ''The Jewish Annotated New Testament'' by Amy-Jill Levine 2011 ISBN 978-0-19-529770-6 page 576</ref> However, these differences are usually seen as indications of the lack of tampering, given that an interpolator would have made the accounts similar.<ref>''Judaism and Hellenism reconsidered'' by Louis H. Feldman 2006 ISBN 90-04-14906-6 pages 330-331</ref> | |||

| The ''Testimonium Flavianumin'' appears in the Greek version of the '']'' (]) and refers to Jesus.<ref name=Schubert38 >''Jewish Traditions in Early Christian Literature'' (Vol 2) by H. Schreckenberg and K. Schubert 1992 ISBN 9023226534 pages 38-41</ref><ref>William Whiston, ''The New Complete Works of Josephus'', Kregel Academic, 1999. p 662</ref> According to Josephus scholar ], the ''Testimonium'' is the most discussed passage in Josephus and perhaps in all ancient literature.<ref name=FeldHata55 >''Josephus, Judaism and Christianity'' by Louis H. Feldman, Gōhei Hata 1997 ISBN 9004085548 pages 55-57</ref> | |||

| Claire Rothschild has stated that the absence of Christian interpolations in the Josephus passage on John the Baptist can not by itself be used as an argument for its authenticity, but is merely an indication of the lack of tampering.<ref>Rothschild, Claire (2011). ""Echo of a Whisper": The Uncertain Authenticity of Josephus' Witness to John the Baptist". In Hellholm, David; Vegge, Tor; Norderval, Øyvind et al. Ablution, Initiation, and Baptism: Late Antiquity, Early Judaism, and Early Christianity. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-024751-0 page 271</ref> | |||

| The first person to cite this passage of the ''Antiquities'' was Eusebius of Caesarea, writing in about 324. In his ''Demonstratio Evangelica,'' he quotes the passage | |||

| ====Testimonium Flavianum==== | |||

| <ref name=eus>{{cite web | |||

| The ''Testimonium'' has been the subject of a great deal of research and debate among scholars, being one of the most discussed passages among all antiquities.{{sfn|Feldman|Hata|1987|p=55}} Louis Feldman has stated that in the period from 1937 to 1980 at least 87 articles had appeared on the topic, the overwhelming majority of which questioned the total or partial authenticity of the ''Testimonium''.<ref name=Feld88Hata430 >''Josephus, the Bible, and History'' by Louis H. Feldman and Gohei Hata 1988 ISBN 0-8143-1982-3 page 430</ref> While early scholars considered the ''Testimonium'' to be a total forgery, the majority of modern scholars consider it partially authentic, despite some clear Christian interpolations in the text.<ref name="Whealey2003">{{cite book|author=Alice Whealey|title=Josephus on Jesus: the testimonium Flavianum controversy from late antiquity to modern times|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=eZUlAQAAIAAJ|accessdate=19 February 2012|year=2003|publisher=Peter Lang|isbn=978-0-8204-5241-8}}</ref><ref>Meier, 1990 (especially note 15)</ref> | |||

| | last = McGiffert | |||

| | first = Arthur Cushman | |||

| | title = Paragraph 7 of "Chapter XI.—Testimonies in Regard to John the Baptist and Christ" from Book I of Eusebius' "The Church History." | |||

| | url= http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf201.iii.vi.xi.html | |||

| | accessdate = 2007-08-12 }} (From the ''Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers,'' Series II, Vol. 1, edited by ].)</ref> in essentially the same form (he has πολλους των Ιουδαιων instead of πολλους Ιουδαιους, and inserts απο before του Ελληνικου). | |||

| As is common with ancient texts, ''The Antiquities of the Jews'' survives only in medieval copies. The manuscripts, the oldest of which dates from the 11th century, are all Greek minuscules, and all have been copied by Christian monks.<ref name="autogenerated1">Feldman (1989), p. 431</ref> Jews did not preserve the writings of Josephus because they considered him to be a traitor. The text of ''Antiquities'' appears to have been transmitted in two halves i.e. (books 1–10 and books 11–20). Other ''ad hoc'' copies of the ''Testimonium'' also survive, as a quotation in the works of Christian writers. | |||

| The arguments surrounding the authenticity of the ''Testimonium'' fall into two categories: internal arguments that rely on textual analysis and compare the passage with the rest of Josephus' work; and external arguments, that consider the wider cultural and historical context.<ref name="Paget2001">{{cite journal|last1=Paget|first1=J. C.|title=Some Observations on Josephus and Christianity|journal=The Journal of Theological Studies|volume=52|issue=2|year=2001|pages=539–624|issn=0022-5185|doi=10.1093/jts/52.2.539}}</ref> Some of the external arguments are "arguments from silence" that question the authenticity of the entire passage not for what it says, but due to lack of references to it among other ancient sources.{{sfn|Van Voorst|2000|pp=91-92}} | |||

| An ancient Table of Contents of the eighteenth book of the ''Antiquities'' omits any reference to the passage about Jesus, as does the Josephus codex of the patriarch ].<ref>Heinz Schreckenberg, Kurt Schubert, ''Jewish Historiography and Iconography in Early and Medieval Christianity'', page 58 (Assen: Van Gorcum, 1992). ISBN 90-232-2653-4</ref> Nor did the ''Testimonium'' exist in the Josephus codex used by the ] ].<ref>Heinz Schreckenberg, Kurt Schubert, page 57.</ref> | |||

| The external analyses of the ''Testimonium'' have even used computer-based methods, e.g. the matching of the text of the ''Testimonium'' with the ] performed by Gary Goldberg in 1995.<ref name=GGoldberg >Goldberg, G. J. 1995 "The Coincidences of the Emmaus Narrative of Luke and the Testimonium of Josephus" ''The Journal for the Study of the Pseudepigrapha'' 13, pp. 59-77 </ref> Goldberg found some partial matches between the ''Testimonium'' and Luke 24:19-21, 26-27, but the results were not conclusive.<ref name=GGoldberg /> Goldberg's analyses suggested three possibilities, one that the matches were random, or that the ''Testimonium'' was a Christian interpolation based on Luke, and finally that both the ''Testimonium'' and Luke were based on the same sources.<ref name=GGoldberg /> | |||

| Michael J. Cook described the content of the ''Testimonium'' as "so adulatory and consistent with what we would expect of a ''Christian'' assessment that most scholars dismiss it as a reworking, even an outright forgery, by a later Christian hand (it was the church, not the rabbis, who preserved Josephus' writings)." <ref>Michael J. Cook, "Jewish Perspectives on Jesus", in Delbert Burkett (editor), ''The Blackwell Companion to Jesus'', page 216 (Wiley-Blackwell, 2010). ISBN 978-1-4051-9362-7</ref> | |||

| =====Internal Arguments===== | |||

| ] | |||

| Scholars have differing views on the authenticity of the ''Testimonium''.<ref>Edwin M. Yamauchi, ''Jesus Outside the New Testament: What is the Evidence?'' p. 212.</ref> The general scholarly view is that while the ''Testimonium Flavianum'' is most likely not authentic in its entirety, it originally possibly consisted of an authentic nucleus with a reference to the execution of Jesus by Pilate which was then subject to interpolation.<ref name=Schubert38 /><ref name=Kellum104 >''The Cradle, the Cross, and the Crown: An Introduction to the New Testament'' by Andreas J. Kostenberger, L. Scott Kellum and Charles L Quarles 2009 ISBN 0805443657 pages 104-108</ref><ref name=Evans316>''Jesus and His Contemporaries: Comparative Studies'' by Craig A. Evans 2001 ISBN 0391041185 page 316</ref><ref name=Henry185>''Jesus and the oral Gospel tradition'' by Henry Wansbrough 2004 ISBN 0567040909 page 185</ref> Although New Testament scholar Robert Van Voorst favours this explanation, he remarks that nothing is certain, and mentions that "other scholars deny the authenticity of the entire passage. Their argument is based on the context of the passage in the ''Antiquities'', the arguably Christian wording of the passage, and Josephus's belief that the Roman general Vespasian was the messiah (''Jewish War'' 6.6.4: 310-13; cf. 3.8.9: 392-408)."<ref>James Leslie Houlden, ''Jesus in History, Thought, and Culture: An Encyclopedia. Entries A - J'', Volume 1, page 510 (ABC-CLIO, Inc., 2003). ISBN 1-57607-856-6</ref> In another work about the ''Testimonium'', Van Voorst adds: "Because the few manuscripts of Josephus come from the eleventh century, long after Christian interpolations would have been made, textual criticism cannot help to solve this issue." Despite this, Van Voorst concludes that Josephus was a "unique and carefully neutral, highly accurate and perhaps independent witness to Jesus." <ref>Robert E. Van Voorst, ''Jesus Outside The New Testament: An Introduction To The Ancient Evidence'', pages 88; 104 (Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2000). ISBN 0-8026-4368-9</ref> | |||

| One of the key internal arguments against the total authenticity of the ''Testimonium'' is that the clear inclusion of Christian phraseology strongly indicates the presence of some interpolations.{{sfn|Van Voorst|2000|p=91}} For instance, the phrases "if it be lawful to call him a man" suggests that Jesus was more than human and is likely a Christian interpolation.{{sfn|Van Voorst|2000|p=91}} Some scholars have attempted to reconstruct the original ''Testimonium'', but others contend that attempts to discriminate the passage into Josephan and non-Josephan elements are inherently circular.{{sfn|Baras|1987|p=340}} | |||

| A number of scholars suggest a relationship between the ''Testimonium'' and the reference to Jesus in ] ] where Josephus refers to the stoning of "James the brother of Jesus". ] views the reference to Jesus in the death of James passage as "the aforementioned Christ", thus relating that passage to the ''Testimonium'', which he views as the first reference to Jesus in the works on Josephus.<ref name=FeldHata55 /> ] concurs with the analysis of Feldman and states that Josephus' first reference was the ''Testimonium''.<ref name=Maier285 /> ] also considers the reference to James as the second reference and states that the first reference is likely to be the ''Testimonium''.<ref name=Geza40>''Jesus in the Jewish World'' by ] 2011 ISBN 0334043794 pages 33-44</ref> Vermes has reconstructed what he considers to be the authentic nucleus of the ''Testimonium'' which contains a reference to the cross and one to the early Christians.<ref name=Geza40/> | |||

| ] states that the fact that the 10th century Arabic version of the ''Testimonium'' (discovered in the 1970s) lacks distinct Christian terminology while sharing the essential elements of the passage indicates that the Greek ''Testimonium'' has been subject to interpolation.{{sfn|Kostenberger|Kellum|Quarles|2009|pp=104-108}} | |||

| ] states that although some portions of the ''Testimonium'' are most likely interpolations, there is strong evidence that some elements of it are authentic.<ref name=Kellum105>The Cradle, the Cross, and the Crown: An Introduction to the New Testament by Andreas J. Köstenberger, L. Scott Kellum 2009 ISBN 9780805443653 pages 105-107</ref> Thomas Yoder Neufeld states that most scholars today consider the core of the ''Testimonium'' reference to have been written by Josphus, then subjected to later extensions.<ref name=Yoder>''Recovering Jesus'' by Thomas Yoder Neufeld 2007 ISBN 1587432021 page 40</ref> ] supports the view that most scholars consider the core of the passage to be authentic.<ref name=Bock>''Studying the historical Jesus: a guide to sources and methods'' by Darrell L. Bock 2002 ISBN 080102451X page 55</ref> ] states that the kernel of the ''Testimoniun'' was likely written by Josephus but was extended later.<ref name=Gerd >''The quest for the plausible Jesus: the question of criteria'' by Gerd Theissen, Dagmar Winter 2002 ISBN 0664225373 page 14</ref> Claudia Setzer states that she agrees with ]'s view that the core of the ''Testimonium'' was written by Josephus, then extended.<ref name=Sezer1 >''Jewish responses to early Christians'' by Claudia Setzer 1994 ISBN 080062680X page 106</ref><ref name=Setzer2>Claudia Setzer "Jewish Responses to believers in Jesus" in ''The Jewish Annotated New Testament'' by Amy-Jill Levine and Marc Z. Brettler 2011 ISBN 0195297709 page 579</ref> Paul D. Wegner also states that a case can be made that the kernel of the ''Testimonium'' was written by Josephus.<ref name=Wegner>''Journey from Texts to Translations'' by Paul D. Wegner 2004 ISBN 0801027993 page 133</ref> | |||

| Another example of the textual arguments against the ''Testimonium'' is that it uses the Greek term ''poietes'' to mean "doer" (as part of the phrase "doer of wonderful works") but elsewhere in his works, Josephus only uses the term ''poietes'' to mean "poet," whereas this use of "poietes" seems consistent with the Greek of Eusebius.<ref name=Mason231 >''Josephus and the New Testament'' by Steve Mason 2003 ISBN 1-56563-795-X page 231</ref> | |||

| Scholars who do not regard the passage as authentic include ], ] and ].<ref>On the ''Testimonium Flavianum'' S. G. F. Brandon commented: "if it had been written by Josephus, must surely mean that he himself was a Christian or at least admitted to the truth of the Christian case. There is reason for thinking however, that this account was either a Christian interpolation or an emendation of something unpalatable that Josephus had actually written about Jesus. The fascination of the problem lies in the fact, which we have noted, that Josephus was eminently well placed for knowing the origins of Christianity; and the value of his testimony as an independent witness would be immense, if it could be recovered." Cited from S.G.F. Brandon (editor), Religion In ''Ancient History: Studies In Ideas, Men and Events'', page 309 (London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd, 1969). ISBN 0-04-2000020-5</ref> Steven Bowman stated that "Eusebius, the polymath ] biographer of Constantine is considered the likely candidate for this pious fraud." <ref>Steven Bowman, "Jewish Responses to Byzantine Polemics from the Ninth through the Eleventh Centuries" , in Zev Garber (editor), ''The Jewish Jesus: Revelation, Reflection, Reclamation'', pages 185-186 (Purdue University Press, 2011). ISBN 978-1-55753-579-5</ref> | |||

| The concordance of the language used in the ''Testimonium'', its flow within the text and its length have formed components of the internal arguments against its authenticity, e.g. that the brief and compact character of the ''Testimonium'' stands in marked contrast to Josephus' more extensive accounts presented elsewhere in his works.<ref name=Wells49/> For example, Josephus' description of the death of ] includes consideration of his virtues, the theology associated with his baptismal practices, his oratorical skills, his influence, the circumstances of his death, and the belief that the destruction of Herod's army was a divine punishment for Herod's slaughter of John.<ref name=MeierJSTOR > {{cite journal | title = John the Baptist in Josephus: philology and exegesis | journal = Journal of Biblical Literature | first = John P. | last = Meier | volume = 111 | issue = 2 | pages = 225–237| id = | jstor = 3267541 | year = 1992 | doi = 10.2307/3267541}}</ref> ] has argued against the authenticity of the ''Testimonium'', stating that the passage is noticeably shorter and more cursory than such notices generally used by Josephus in the ''Antiquities'', and that had it been authentic, it would have included more details and a longer introduction.<ref name=Wells49/> | |||

| J. Neville Birdsall in 1984 argued that the whole of the ''Testimonium Flavianum'' was a Christian interpolation in The Manson Memorial Lecture, on the grounds of linguistics.<ref>J. Neville Birdsall, "The Continuing Enigma of Josephus's Testimony about Jesus", pages 609-622, ''Bulletin of the John Rylands University Library'' (1984-1985).</ref> | |||

| A further internal argument against the ''Testimonium's'' authenticity is the context of the passage in the ''Antiquities of the Jews''.{{sfn|Van Voorst|2003|p=509}} Some scholars argue that the passage is an intrusion into the progression of Josephus' text at the point in which it appears in the ''Antiquities'' and breaks the thread of the narrative.<ref name=Wells49>''The Jesus Legend'' by George Albert Wells and R. Joseph Hoffman 1996 ISBN 0-8126-9334-5 pages 49-56</ref> | |||

| ==Slavonic Josephus== | |||

| =====External Arguments===== | |||

| The three references found in ] and | |||

| ]]] | |||

| ] of the ''Antiquities'' do not appear in any other versions of Josephus' '']'' except for a ] version of the ''Testimonium Flavomium'' (at times called ''Testimonium Slavonium'') which surfaced in the west at the beginning of the 20th century, after its discovery in Russia at the end of the 19th century.<ref name="Robert E. Van Voorst page 85"/><ref name=Creed/> | |||

| Origen's statement in his ''Commentary on Matthew'' (]) that Josephus" did not accept Jesus as Christ", is usually seen as a confirmation of the generally accepted fact that Josephus did not believe Jesus to be the Messiah.{{sfn|Van Voorst|2000|p=97}}<ref name=JContext91 >Jesus in his Jewish context'' by Géza Vermès 2003 ISBN 0-334-02915-5 pages 91-92</ref> This forms a key external argument against the total authenticity of the ''Testimonium'' in that Josephus, as a Jew, would not have claimed Jesus as the Messiah, and the reference to "he was Christ" in the ''Testimonium'' must be a Christian interpolation.{{sfn|Maier|2007|pp=336-337}} Based on this observation alone, ] calls the case for the total authenticity of the ''Testimonium'' "hopeless".{{sfn|Maier|2007|pp=336-337}} Almost all modern scholars reject the total authenticity of the ''Testimonium'', while the majority of scholars still hold that it includes an authentic kernel.{{sfn|Maier|2007|pp=336-337}}{{sfn|Van Voorst|2003|pp=509-511}} | |||

| ] | |||

| A different set of external arguments against the authenticity of the ''Testimonium'' (either partial or total) are "]", e.g. that although twelve Christian authors refer to Josephus before Eusebius in 324 AD, none mentions the ''Testimonium''.<ref name=Rothchild274 >"Echo of a whisper" by Clare Rothchild in ''Ablution, Initiation, and Baptism: Late Antiquity, Early Judaism, and Early Christianity'' by David Hellholm 2010 ISBN 3-11-024751-8 page 274</ref>{{sfn|Feldman|Hata|1987|p=57}} Given earlier debates by Christian authors about the existence of Jesus, e.g. in ]'s 2nd century '']'', it would have been expected that the passage from Josephus would have been used as a component of the arguments.{{sfn|Feldman|Hata|1987|p=431}} | |||