| Revision as of 02:31, 16 July 2012 editMedeis (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users49,187 edits restore neutral well-written material← Previous edit | Revision as of 02:37, 16 July 2012 edit undoMedeis (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users49,187 edits →See alsoNext edit → | ||

| Line 105: | Line 105: | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| Today, the ] in New York City is a major center for Roerich's artistic work. Numerous Roerich societies continue to promote his theosophical teachings worldwide. His paintings can be seen in several museums including the Roerich Department of the State Museum of Oriental Arts in Moscow; the Roerich Museum at the International Centre of the Roerichs in Moscow; the Russian State Museum in Saint Petersburg, Russia; a collection in the ] in ]; a collection in the Art Museum in ], Russia; a collection in the Art Museum in ], Russia; the Roerich Hall Estate in Nagar village, Kulu Valley, Himachal-Pradesh (India); in various art museums in India; and a selection featuring several of his larger works in ]. | Today, the ] in New York City is a major center for Roerich's artistic work. Numerous Roerich societies continue to promote his theosophical teachings worldwide. His paintings can be seen in several museums including the Roerich Department of the State Museum of Oriental Arts in Moscow; the Roerich Museum at the International Centre of the Roerichs in Moscow; the Russian State Museum in Saint Petersburg, Russia; a collection in the ] in ]; a collection in the Art Museum in ], Russia; a collection in the Art Museum in ], Russia; the Roerich Hall Estate in Nagar village, Kulu Valley, Himachal-Pradesh (India); in various art museums in India; and a selection featuring several of his larger works in ]. | ||

| ==Dialogue and video recording with Roerich== | |||

| {| width=100 % align=center | |||

| |{{Listen | |||

| |filename = "About Shambala" N.Roerich.ogg | |||

| |title = N. K. Roerich. About Shambala | |||

| |description = Phonogram of 1929. | |||

| }} | |||

| | ] | |||

| |} | |||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

Revision as of 02:37, 16 July 2012

| Nicholas Roerich | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | (1874-10-09)October 9, 1874 Saint Petersburg, Russia |

| Died | December 13, 1947(1947-12-13) (aged 73) Punjab, India |

| Nationality | Russia |

| Occupation(s) | painter, archaeologist, costume and set designer for ballets, operas, and dramas |

| Spouse | Helena Roerich |

| Children | George de Roerich, Svetoslav Roerich |

Nicholas Roerich, (October 9, 1874 - December 13, 1947) also known as Nikolai Konstantinovich Rerikh (alternative transliteration) (Template:Lang-ru), was a Russian painter and philosopher.

Born in Saint Petersburg, Russia to the family of a well-to-do notary public, he lived around the world until his death in Punjab, India. Trained as an artist and a lawyer, his interests lay in literature, philosophy, archaeology and especially art. Roerich was a dedicated activist for the cause of preserving art and architecture in times of war. He earned several nominations for the Nobel Prize. The so-called Roerich Pact was signed into law by the United States and most member nations of the Pan-American Union in April 1935.

Biography

Early life

Raised in turn-of-the-century St. Petersburg, Roerich matriculated simultaneously at St. Petersburg University and the Imperial Academy of Arts in 1893. He received the title of "artist" in 1897 and a degree in law the following year. He found early employment with the Imperial Society for the Encouragement of the Arts, whose school he directed from 1906 to 1917. Despite early tensions with the group, he became a member of Sergei Diaghilev's "World of Art" society; he chaired the society from 1910 to 1916.

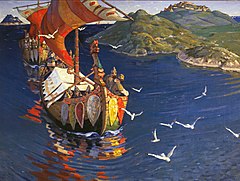

Artistically, he made a mark as his generation's most talented painter of Russia's ancient past, a subject that meshed well with his lifelong interest in archaeology. He also succeeded in the field of stage design, achieving his greatest fame as one of the designers for Diaghilev's Ballets Russes. His best-known designs were for Borodin's Prince Igor (1909 and later productions), and costumes and set for The Rite of Spring (1913), composed by Igor Stravinsky.

Another of Roerich's passions was architecture. His acclaimed "Architectural Studies" (1904-1905) -- the dozens of paintings he completed of fortresses, monasteries, churches, and other monuments during two long trips through Russia -- inspired his decades-long career as an activist on behalf of artistic and architectural preservation. He also designed religious art for places of worship throughout Russia and Ukraine, most notably the Queen of Heaven fresco for the Church of the Holy Spirit which the patroness Maria Tenisheva built near her Talashkino estate.

During the 1900s and early 1910s, Roerich, largely due to the influence of his wife Helena, developed an interest in eastern religions, as well as alternative belief systems such as Theosophy. Both Roerichs became avid readers of the Vedantist essays of Ramakrishna and Vivekananda, the poetry of Rabindranath Tagore, and the Bhagavad Gita. The Roerichs' commitment to occult mysticism steadily increased. It was brought to a new pitch during World War I and the Russian revolutions of 1917, to which the couple, like many Russian intellectuals, attached apocalyptic significance. The influence of Theosophy, Vedanta, Buddhism, and other mystical strains of thought can be seen not only in many of his paintings, but in the many short stories and poems Roerich wrote before and after the 1917 revolutions, including the Flowers of Morya cycle, begun in 1907 and completed in 1921.

Revolution, emigration, and the United States

After the February Revolution of 1917 and the collapse of the tsarist regime, Roerich, a political moderate who placed spiritual values and Russia's cultural heritage above ideology and party politics, played an active part in artistic politics. With Maxim Gorky and Aleksandr Benois, he participated in the so-called "Gorky Commission" and its successor organization, the Arts Union (SDI). Both attempted to focus the Provisional Government's and Petrograd Soviet's attention on the need to form a coherent cultural policy and, most urgently, protect art and architecture from destruction and vandalism. At the same time, however, illness forced Roerich to leave the capital and reside in Karelia, the district bordering Finland. He had already resigned the chair of the World of Art society, and he now gave up the directorship of the School of the Imperial Society for the Encouragement of the Arts. After the October Revolution and the rise to power of Lenin's Bolshevik Party, Roerich grew increasingly discouraged about Russia's political future. In early 1918, he, Helena, and their two sons George and Sviatoslav emigrated to Finland.

Two unresolved historical debates are associated with Roerich's departure. First, it is often claimed that Roerich was a leading candidate to head a people's commissariat of culture (the Soviet equivalent of a ministry of culture) which the Bolsheviks considered establishing in 1917-1918, but that he refused to take up the post. In fact, Benois was the most likely pick to lead any such commissariat. It appears that Roerich was a preferred choice to run its department of artistic education; the point is rendered moot by the fact that the Soviets elected not to establish such a commissariat. Second, when he wished to reconcile with the USSR, Roerich later maintained that he had not left Soviet Russia deliberately, but that he and his family, living in Karelia, had been cut off from their homeland when civil war broke out in Finland. However, Roerich's extreme hostility to the Bolshevik regime - prompted not so much by a dislike of communism as by his revulsion at Lenin's ruthlessness and his fear that Bolshevik rule would lead to the destruction of Russia's artistic and architectural heritage - was amply documented. He illustrated Leonid Andreyev's anti-communist polemic "S.O.S." and had a widely published pamphlet, "Violators of Art" (1918-1919). Roerich believed that "the triumph of Russian culture would come about through a new appreciation of ancient myth and legend".

After some months in Finland and Scandinavia, the Roerichs moved on to London, arriving in mid-1919. Fully engrossed in Theosophical mysticism, the Roerichs were now consumed by millenarian expectations that a new age was imminent, and they wished to reach India as soon as possible. They joined the English-Welsh chapter of the Theosophical Society. It was in London, in March 1920, that the Roerichs founded their own school of occult thinking, Agni Yoga, which they also referred to as "the system of living ethics." To earn passage to India, Roerich worked as a stage designer for Thomas Beecham's Covent Garden Theatre, but the enterprise collapsed in 1920, and the artist never received full payment for his work.

Luckily, a successful exhibition led to an invitation from a director at the Chicago Art Institute, offering to arrange for Roerich's art to tour the United States. In the fall of 1920, the Roerichs set sail for America. Among the notable people Roerich befriended while in England were the famed British Buddhist Christmas Humphreys, philosopher-author H. G. Wells, and the poet and Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore (whose grand-niece Devika Rani would later marry Roerich's son Sviatoslav).

The Roerichs remained in the United States from October 1920 to May 1923. A large exhibition of Roerich's art, organized in part by U.S. impresario Christian Brinton and in part by the Chicago Art Institute, opened in New York in December 1920 and toured the country, to San Francisco and back, in 1921 and early 1922. Roerich befriended acclaimed soprano Mary Garden of the Chicago Opera and received a commission to design a 1922 production of Rimsky-Korsakov's The Snow Maiden for her. During the exhibition, the Roerichs spent significant amounts of time in Chicago, New Mexico, and California.

They settled in New York City, which became the base of their many American operations. The Roerichs founded several institutions during these years: Cor Ardens and Corona Mundi, both of which were meant to unite artists around the globe in the cause of civic activism; the Master Institute of United Arts, an art school with an exceptionally versatile curriculum, and the eventual home of the first Nicholas Roerich Museum; and an American Agni Yoga Society. They also joined various theosophical societies, and their activities in these groups dominated their lives.

Asian Expedition (1925-1928)

After leaving New York, the Roerichs - together with their son George and six friends - went on the five-year long 'Roerich Asian Expedition' that, in Roerich's own words: "started from Sikkim through Punjab, Kashmir, Ladakh, the Karakoram Mountains, Khotan, Kashgar, Qara Shar, Urumchi, Irtysh, the Altai Mountains, the Oryot region of Mongolia, the Central Gobi, Kansu, Tsaidam, and Tibet" with a detour through Siberia to Moscow in 1926. Roerichs' Asian expedition attracted anxious attention from the foreign services and intelligence agencies of the USSR, the United States, Great Britain, and Japan. Between the summer of 1927 and June of 1928 the expedition was thought to be lost, since all contact from them ceased for a year. They had been attacked in Tibet and only the "Superiority of our firearms prevented bloodshed... In spite of our having Tibet passports, the expedition was forcibly stopped by Tibetan authorities." The expedition was detained by the government for five months, and forced to live in tents in sub-zero conditions and to subsist on meagre rations. Five men of the expedition died at this time. In March of 1928 they were allowed to leave Tibet, and trekked south to settle in India, where they founded a research center, the Himalayan Research Institute.

Cultural work

In 1929 Nicholas Roerich was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize by the University of Paris. He received two more nominations in 1932 and 1935. His concern for peace led to his creation of the Pax Cultura, the "Red Cross" of art and culture. His work in this area also led the United States and the twenty other members of the Pan-American Union to sign the Roerich Pact on April 15, 1935 at the White House. The Roerich Pact is an early international instrument protecting cultural property.

Vice President of the United States Henry A. Wallace was a frequent correspondent and sometime follower of Roerich's teachings. This became controversial when Wallace ran for President in 1948 and portions of the letters were printed by Hearst Newspapers columnist Westbrook Pegler.

Cultural references

H.P. Lovecraft referred to the "strange and disturbing paintings of Nicholas Roerich" in his Antarctic horror story At the Mountains of Madness.

Legacy

Today, the Nicholas Roerich Museum in New York City is a major center for Roerich's artistic work. Numerous Roerich societies continue to promote his theosophical teachings worldwide. His paintings can be seen in several museums including the Roerich Department of the State Museum of Oriental Arts in Moscow; the Roerich Museum at the International Centre of the Roerichs in Moscow; the Russian State Museum in Saint Petersburg, Russia; a collection in the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow; a collection in the Art Museum in Novosibirsk, Russia; a collection in the Art Museum in Nizhny Novgorod, Russia; the Roerich Hall Estate in Nagar village, Kulu Valley, Himachal-Pradesh (India); in various art museums in India; and a selection featuring several of his larger works in The Latvian National Museum of Art.

Dialogue and video recording with Roerich

Problems playing this file? See media help. |

See also

- Agni Yoga

- Pax Cultura

- Helena Roerich

- Svetoslav Roerich

- George de Roerich

- Yuli Mikhailovich Vorontsov — President of International Centre of the Roerichs (Moscow)

- 4426 Roerich — Minor planet in Solar System

External links

- International Centre of the Roerichs

- Nicholas Roerich Museum (New York)

- International Non-governmental Organisation "The International Centre of the Roerichs" (Russia)

- International Roerich Memorial Trust (India)

- Agni Yoga Society

- Estonian Roerich Society

- Roerich-movement on the Internet (in Russian)

- Reviving the Roerich Banner of Peace: Peace Through Culture!

- Paintings Gallery

- Nicholas Roerich Estate Museum in Izvara

- Roerich Family

References

-

Рерих Николай Константинович // Большая биографическая энциклопедия

- — Рерих Николай Константинович // Русская философия: словарь/Под общ. ред. М. А. Маслина / В. В. Сапов. — М.: Республика, 1995

- — Рерих Николай Константинович // Краткий философский словарь / А. П. Алексеев, Г. Г. Васильев и др.; Под ред. А. П. Алексеева — 2-е изд., перераб. и доп. — М.: ТК Велби, Изд-во Проспект, 2004.

- — Рерих Николай Константинович // С. Левит. Культурология. XX век. Энциклопедия., 1998 г.

- — Рерих Николай Константинович / Новейший философский словарь /Грицанов А. А.. — Научное издание. — Минск: В. М. Скакун, 1999 г. — 896 с.

- — Рерих Николай Константинович // Биографический словарь

- — Рерих Николай Константинович // Современная энциклопедия

- — Рерих Николай Константинович // Большая советская энциклопедия

- — Рерих Николай Константинович // Энциклопедический словарь Ф. А. Брокгауза и И. А. Ефрона

- — Рерих Николай Константинович // Энциклопедия «Кругосвет»

- — Рерих Николай Константинович // Современный Энциклопедический словарь. Изд. «Большая Российская Энциклопедия», 1997 г.

- — Nikolay Roerich // Gallery of Russian Thinkers

- — Nikolai Konstantinowitsch Roerich / Meyers Konversations Lexikon. Online-version

- Bowlt, John E. (2008). Moscow and St. Petersburg 1900-1920: Art, Life and Culture. New York: The Vendome Press. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-86565-191-3.

- "Roerich Nominated for Peace Award". New York Times. March 3, 1929. Retrieved 2009-02-03.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Nomination database