| Revision as of 00:38, 29 June 2013 editRjensen (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, File movers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers227,309 edits →Construction history: cites; Stevens← Previous edit | Revision as of 00:56, 1 July 2013 edit undoRjensen (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, File movers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers227,309 edits →Construction history: cleanupNext edit → | ||

| Line 26: | Line 26: | ||

| ==Construction history== | ==Construction history== | ||

| The Great Northern was built in stages, slowly to create profitable lines, before extending the road further into the undeveloped Western territories. In a series of the earliest public relations campaigns, contests were held to promote interest in the railroad and the ranchlands along its route. Fred J. Adams used promotional incentives such as feed and seed donations to farmers getting started along the line. Contests were all-inclusive, from largest farm animals to largest freight carload capacity and were promoted heavily to immigrants & newcomers from the East.<ref |

The Great Northern was built in stages, slowly to create profitable lines, before extending the road further into the undeveloped Western territories. In a series of the earliest public relations campaigns, contests were held to promote interest in the railroad and the ranchlands along its route. Fred J. Adams used promotional incentives such as feed and seed donations to farmers getting started along the line. Contests were all-inclusive, from largest farm animals to largest freight carload capacity and were promoted heavily to immigrants & newcomers from the East.<ref>Martin, ''James J. Hill,'' ch 12</ref> | ||

| The earliest predecessor railroad to the GN was the ], a bankrupt railroad with a small amount of track in the state of Minnesota. Hill convinced ] (a New York banker), ] (Hill's friend and a wealthy fur trader), ] (an executive with Canada's ]), ] (Smith's cousin and president of the Bank of Montreal), and others to invest $5.5 million in purchasing the railroad.<ref>Malone, p. 38-41.</ref> On March 13, 1878, the road's creditors formally signed an agreement transferring their bonds and control of the railroad to Hill's investment group.<ref>Malone. p. 49.</ref> On September 18, 1889, Hill changed the name of the ] (a railroad which existed primarily on paper, but which held very extensive land grants throughout the Midwest and Pacific Northwest) to the Great Northern Railway. |

The earliest predecessor railroad to the GN was the ], a bankrupt railroad with a small amount of track in the state of Minnesota. Hill convinced ] (a New York banker), ] (Hill's friend and a wealthy fur trader), ] (an executive with Canada's ]), ] (Smith's cousin and president of the Bank of Montreal), and others to invest $5.5 million in purchasing the railroad.<ref>Malone, p. 38-41.</ref> On March 13, 1878, the road's creditors formally signed an agreement transferring their bonds and control of the railroad to Hill's investment group.<ref>Malone. p. 49.</ref> On September 18, 1889, Hill changed the name of the ] (a railroad which existed primarily on paper, but which held very extensive land grants throughout the Midwest and Pacific Northwest) to the Great Northern Railway. On February 1, 1890, he transferred ownership of the StPM&M, ], and other rail systems he owned to the Great Northern.<ref name="Yenne23" /> | ||

| The Great Northern had branches that ran north to the Canadian border in Minnesota, North Dakota and Montana. It also had branches that ran to ], and ], connecting with the iron mining fields of Minnesota and copper mines of Montana. In 1898 Hill purchased control of large parts of the Messabe Range iron mining district in Minnesota, along with its rail lines. The Great Northern began large-scale shipment of ore to the steel mills of the Midwest.<ref>Don L. Hofsommer, "Ore Docks and Trains: The Great Northern Railway and the Mesabi Range," ''Railroad History'' (1996) Issue 174, pp 5-25</ref> At its height Great Northern operated over 8,000 miles. | The Great Northern had branches that ran north to the Canadian border in Minnesota, North Dakota and Montana. It also had branches that ran to ], and ], connecting with the iron mining fields of Minnesota and copper mines of Montana. In 1898 Hill purchased control of large parts of the Messabe Range iron mining district in Minnesota, along with its rail lines. The Great Northern began large-scale shipment of ore to the steel mills of the Midwest.<ref>Don L. Hofsommer, "Ore Docks and Trains: The Great Northern Railway and the Mesabi Range," ''Railroad History'' (1996) Issue 174, pp 5-25</ref> At its height Great Northern operated over 8,000 miles. | ||

Revision as of 00:56, 1 July 2013

| |

Great Northern route map circa 1920. Red lines are GN; dotted lines are other railroads. Great Northern route map circa 1920. Red lines are GN; dotted lines are other railroads. | |

An EMD F7 in GN paint An EMD F7 in GN paint | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | Saint Paul, Minnesota |

| Reporting mark | GN |

| Locale | Saint Paul, Minnesota to Seattle, Washington |

| Dates of operation | ca. 1890–1970 |

| Successor | Burlington Northern |

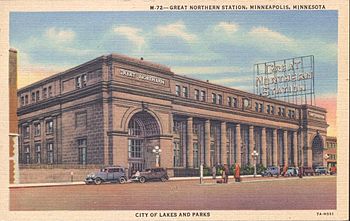

The Great Northern Railway (reporting mark GN), running from Saint Paul, Minnesota, to Seattle, Washington—more than 1,700 miles (2,736 km)—was the creation of the 19th century railroad tycoon James J. Hill and was developed from the Saint Paul and Pacific Railroad. The Great Northern's route was the northernmost transcontinental railroad route in the United States. It was completed on January 6, 1893, at Scenic, Washington.

The Great Northern was the only privately funded, and successfully built, transcontinental railroad in United States history. No federal land grants were used during its construction, unlike every other transcontinental railroad; according to Hill, his railway was built "without any government aid, even the right of way, through hundreds of miles of public lands, being paid for in cash". Consequently, it was one of the few transcontinental railroads to avoid receivership following the Panic of 1893.

The Great Northern Railway fell victim to the deadliest avalanche in United States history, at the site of the now non-existent town of Wellington, Washington (later renamed, due to the disaster, to Tye, Washington).

At the end of 1967, GN operated 8282 route-miles, not including class II subsidiaries MA&CR (3 miles) and PC (32 miles).

Construction history

The Great Northern was built in stages, slowly to create profitable lines, before extending the road further into the undeveloped Western territories. In a series of the earliest public relations campaigns, contests were held to promote interest in the railroad and the ranchlands along its route. Fred J. Adams used promotional incentives such as feed and seed donations to farmers getting started along the line. Contests were all-inclusive, from largest farm animals to largest freight carload capacity and were promoted heavily to immigrants & newcomers from the East.

The earliest predecessor railroad to the GN was the St. Paul & Pacific Railroad, a bankrupt railroad with a small amount of track in the state of Minnesota. Hill convinced John S. Kennedy (a New York banker), Norman Kittson (Hill's friend and a wealthy fur trader), Donald Smith (an executive with Canada's Hudson's Bay Company), George Stephen (Smith's cousin and president of the Bank of Montreal), and others to invest $5.5 million in purchasing the railroad. On March 13, 1878, the road's creditors formally signed an agreement transferring their bonds and control of the railroad to Hill's investment group. On September 18, 1889, Hill changed the name of the Minneapolis and St. Cloud Railway (a railroad which existed primarily on paper, but which held very extensive land grants throughout the Midwest and Pacific Northwest) to the Great Northern Railway. On February 1, 1890, he transferred ownership of the StPM&M, Montana Central Railway, and other rail systems he owned to the Great Northern.

The Great Northern had branches that ran north to the Canadian border in Minnesota, North Dakota and Montana. It also had branches that ran to Superior, Wisconsin, and Butte, Montana, connecting with the iron mining fields of Minnesota and copper mines of Montana. In 1898 Hill purchased control of large parts of the Messabe Range iron mining district in Minnesota, along with its rail lines. The Great Northern began large-scale shipment of ore to the steel mills of the Midwest. At its height Great Northern operated over 8,000 miles.

| Year | Traffic |

|---|---|

| 1925 | 8521 |

| 1933 | 5434 |

| 1944 | 19583 |

| 1960 | 15831 |

| 1967 | 17938 |

The railroad’s best known engineer, 1889 to 1903, was John Frank Stevens. Stevens earned wide acclaim in 1889 when he explored Marias Pass, Montana, and determined its practicability for a railroad. Stevens was an efficient administrator with remarkable technical skills and imagination. He discovered Stevens Pass through the Cascade Mountains, set railroad construction standards in the Mesabi Range of northern Minnesota, and supervised construction of the Oregon Trunk Line, which opened in 1911. He then became the chief engineer in charge of building the Panama Canal.

Mainline

The mainline began at Saint Paul, Minnesota, heading west and topping the bluffs of the Mississippi River, crossing the river to Minneapolis on a massive multi-piered stone bridge. The Stone Arch Bridge stands in Minneapolis, near the Saint Anthony Falls, the only waterfall on the Mississippi. The bridge ceased to be used as a railroad bridge in 1978 and is now used as a pedestrian river crossing with excellent views of the falls and of the lock system used to grant barges access up the river past the falls. The mainline headed northwest from the Twin Cities, across North Dakota and eastern Montana. The line then crossed the Rocky Mountains at Marias Pass, and then followed the Flathead River and then Kootenai River to Athol, Idaho and Spokane, Washington. From here, the mainline crossed the Cascade Mountains through the Cascade Tunnel under Stevens Pass, reaching Seattle, Washington in 1893, with the driving of the last spike at Scenic, Washington, on January 6, 1893.

The Great Northern mainline crossed the continental divide through Marias Pass, the lowest crossing of the Rockies south of the Canadian border. Here, the rails enter Glacier National Park, which the GN promoted heavily as a tourist attraction. GN constructed stations at East Glacier and West Glacier entries to the park, stone and timber lodges at the entries and other inns & lodges throughout the Park. Many of the structures have been listed on the National Register of Historic Places due to unique construction, location and the beauty of the surrounding regions.

In 1931 the GN also developed the "Inside Gateway," a route to California that rivaled the Southern Pacific Railroad's route between Oregon and California. The GN route was further in-land than the SP route and ran south from the Columbia River in Oregon. The GN connected with the Western Pacific at Bieber, California; the Western Pacific connected with the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe in Stockton, California, and together the three railroads (GN, WP, and ATSF) competed with Southern Pacific for traffic between California and the Pacific Northwest. With a terminus at Superior, Wisconsin, the Great Northern was able to provide transportation from the Pacific to the Atlantic by taking advantage of the shorter distance to Duluth from the ocean, as compared to Chicago.

Settlements

The Great Northern energetically promoted settlement along its lines in North Dakota and Montana, especially by German and Scandinavians from Europe. The Great Northern bought its lands from the federal government—it received no land grants—and resold them to farmers one by one. It operated agencies in Germany and Scandinavia that promoted its lands, and brought families over at low cost. The rapidly increasing settlement in North Dakota's Red River Valley along the Minnesota border between 1871 and 1890 was a major example of large-scale "bonanza" farming.

Later history

In 1970 the Great Northern, together with the Northern Pacific Railway, the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad and the Spokane, Portland and Seattle Railway merged to form the Burlington Northern Railroad. The BN operated until 1996, when it merged with the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway to form the Burlington Northern and Santa Fe Railway.

The Great Northern Railway is considered to have inspired (in broad outline, not in specific details) the Taggart Transcontinental railroad in Ayn Rand's Atlas Shrugged.

Passenger service

The Great Northern operated various passenger trains but the Empire Builder was the GN's premier passenger train. The Empire Builder was named in honor of Great Northern's founder James J. Hill, who was known as the "Empire Builder."

Named trains

- Alexandrian: St. Paul–Fargo - (1931–

- Badger Express: St. Paul-Superior/Duluth (later renamed Badger)

- Cascadian: Seattle - Spokane (1909-1959)

- Dakotan: St. Paul-Minot

- Eastern Express Seattle-St. Paul (1903-1906) (replaced by Fast Mail in 1906)

- Empire Builder: Chicago-Seattle/Chicago-Portland (1929–present)

- Fast Mail No.27: St. Paul–Seattle (1906-1910) (renamed The Oregonian in 1910)

- Glacier Park Limited: St. Paul–Seattle (1915-1929) (replaced by Oriental Limited in 1929)

- Gopher: St. Paul-Superior/Duluth

- Great Northern Express: (1909-1918) Kansas City-Seattle

- International: Seattle-Vancouver, B.C.

- Oregonian : St. Paul–Seattle (1910-1915) (replaced by Glacier Park Limited in 1915)

- Oriental Limited : Chicago-St. Paul-Seattle (replaced by Western Star in 1951)

- Puget Sound Express: St. Paul-Seattle (1903-1906) (replaced by Fast Mail in 1906)

- Red River Limited: Grand Forks-St. Paul (later renamed Red River)

- Seattle Express, No. 25

- Southeast Express: (1909-1918) Seattle-Kansas City

- Western Star : Chicago-St. Paul-Seattle-Portland

- Winnipeg Limited: St. Paul-Winnipeg

Unnamed trains

- Train Nos. 23-30: St. Cloud–Grand Forks via Barnesville and Crookston local

- Train Nos. 31-32: Sandstone-Willmar via St. Cloud local

- Train Nos. 35-36: Duluth-Grand Forks via Superior and Crookston local

- Train Nos. 43-42: Billings-Sweetgrass via Great Falls and Shelby local

- Train Nos. 43-42: Billings-Great Falls local – using GN's only Budd Rail Diesel Car

- Train Nos. 47-48-49-50: Morris-Browns Valley shuttle

- Train Nos. 53-54: Watertown-Sioux Falls local

- Train Nos. 61-60: Minneapolis-Hutchinson via Wayzata local

- Train Nos. 99-100: Fargo-Minot via Grand Forks local

- Train Nos. 105-106: Sauk Center-Bemidji via Cass Lake local

- Train Nos. 131-132: Crookston-Noyes local

- Train Nos. 135-136: Crookston-Warroad local

- Train Nos. 161-162: Garretson-Sioux City local

- Train Nos. 185-186: Willmar-Huron via Benson local

- Train Nos. 197-198: Breckenridge-Larimore via Vance local

- Train Nos. 201-202: Grand Forks-Larimore local

- Train Nos. 215-215: Neilhart-Great Falls local

- Train Nos. 219-220: Berthold-Crosby local

- Train Nos. 221-222: Havre-Great Falls local

- Train Nos. 223-224: Williston-Havre local

- Train Nos. 235-236: Havre-Great Falls Western Star connection – later used GN's only Budd Rail Diesel Car

- Train Nos. 237-238: Havre-Great Falls Empire Builder connection

- Train Nos. 243-244-245-246-247-248-249-250: Columbia Falls-Kalispell shuttle

- Train Nos. 253-254: Oroville-Wenatchee local

- Train Nos. 255-256: Nelson, BC-Spokane local

- Train Nos. 285-286: Snowden-Richey via Fairview local

- Train Nos. 287-288: Watford City-Fairview local

- Train Nos. 291-292: Fairview-Sidney local

- Train Nos. 301-302: Fergus Falls-Pelican Rapids local

- Train Nos. 317-318: Sioux Falls-Yankton local

- Train Nos. 359-358: Vancouver, BC-Seattle local

- Train Nos. 365-366: Great Falls-Augusta local

- Train Nos. 367-368: Lewiston-Moccasin local

- Train Nos. 373-374: Great Falls-Pendroy local

- Train Nos. 401-402: Seattle-Portland (4 months per year) – joint Coast Pool train with Northern Pacific Railway and Union Pacific Railroad

- Train Nos. 459-460: Seattle-Portland – joint Coast Pool train with Northern Pacific Railway and Union Pacific Railroad

Amtrak's Empire Builder

Today, Amtrak's Empire Builder uses the line, running mostly on ex-GN trackage (between the Twin Cities terminal and St. Cloud, Minnesota; Moorhead, Minnesota and Sandpoint, Idaho, and between Spokane, Washington and Seattle).

Electrification

In 1909 the Great Northern Railway electrified the 2.5-mile (4.0 km) original Cascade Tunnel, which was near the summit of Stevens Pass in the Cascade Mountains. The electrified section was of 4.0-mile (6.4 km) route-miles or 6.0-mile (9.7 km) track-miles, with 1.7 percent grade through the tunnel. The system using 6600 volts 25 Hz was the only three-phase A.C. system ever used on North America railroads, see Three-phase AC railway electrification. Four 1500 hp locomotives of 115 tons each were supplied by the American Locomotive Co. Later GE-built electric boxcabs were used. They pulled trains through the tunnel with the steam locomotives still attached until they were retired from March 27, 1927. This was before the opening of the new tunnel, and the old tunnel and 8-mile (13 km) of the track to be abandoned was converted to the new single phase A.C. electrification system, using 11 Kv, 25 Hz supply and one instead of two overhead wires.

The new lower Cascade Tunnel of 7.8-mile (12.6 km) opened on January 12, 1929. Work had started in 1925 on the new route, and the electrification of a 73-mile (117 km) section of its main line route to Seattle, Washington, from Wenatchee to Skykomish. The new tunnel and electrification reduced the mainline by 9 miles (14 km), eliminated 502 feet (153 m) of elevation and 6 miles (9.7 km) of snow sheds. The new Baldwin-Westinghouse Z-1 electric locomotive consisted of a pair of semi-permanently coupled 1-D-1 box-cab units. The pair weighed over 371 tons, with an hourly rating of 4330 hp. They were used exclusively on this section, for both mainline freight and passenger trains. GN W-1 and GN Y-1 locomotives were also used.

The route was de-energized and dismantled in 1956, after the Cascade Tunnel was fitted with ventilation fans.

See also

- Western Fruit Express

- Cascade Tunnel

- Defunct railroads of North America

- Great Northern Railway: Mansfield Branch (1909-1985)

- Glacier National Park (U.S.)

- W-1 GN's largest electric locomotive

References

- Albro, Martin (1976). James J. Hill and the Opening of the Northwest. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 411.

- Martin, James J. Hill, ch 12

- Malone, p. 38-41.

- Malone. p. 49.

- Cite error: The named reference

Yenne23was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - Don L. Hofsommer, "Ore Docks and Trains: The Great Northern Railway and the Mesabi Range," Railroad History (1996) Issue 174, pp 5-25

- Ralph W. Hidy, and Muriel E. Hidy, “John Frank Stevens, Great Northern Engineer,” Minnesota History (1969) 41#8 pp 345-361

- Stanley N. Murray, "Railroads and the Agricultural Development of the Red River Valley of the North, 1870-1890," Agricultural History, (1957) 31#4 pp 57-66 in JSTOR

- David H. Hickcox, "The Impact of the Great Northern Railway on Settlement in Northern Montana, 1880-1920," Railroad History, (1983), Issue 148, pp 58-67

- Robert F. Zeidel, "Peopling the Empire: The Great Northern Railroad and the Recruitment of Immigrant Settlers to North Dakota," North Dakota History, (1993), 60#2 pp 14-23

- Ayn Rand, Leonard Peikoff, Peter Schwartz, The voice of reason: essays in objectivist thought (New American Library, 1989), pg. 92

- ^ "Glacier Park Limited". Ted's Great Northern Homepage. Retrieved 6 March 2012.

- ^ "Transcontinental Trains". Ted's Great Northern Homepage. Retrieved 6 March 2012.

- "Great Northern Express". Ted's Great Northern Homepage. Retrieved 6 March 2012.

- NWDA Washington State University: Wellington Disaster

- "Three Daily Trains". Great Northern Railway. circa 1912. Retrieved 6 March 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)

Bibliography

- Malone, Michael P. James J. Hill: Empire Builder of the Northwest. Norman, Okla.: University of Oklahoma Press, 1996.

- Yenne, Bill. Great Northern Empire Builder. St. Paul, Minn.: MBI Publishing, 2005.

Further reading

- Whitney, F.I. (1894). "Valley, Plain and Peak..Scenes on the line of the Great northern railway". St. Paul, Minn.: Great Northern Railway Office of the general passenger and ticket agent.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)

- Wood, Charles (1989). Great Northern Railway. Edmonds, WA: Pacific Fast Mail. ISBN 0-915713-19-5.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Sobel, Robert (1974). "Chapter 4: James J. Hill". The Entrepreneurs: Explorations within the American business tradition. Weybright & Talley. ISBN 0-679-40064-8.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Wilson, Jeff (2000). Great Northern Railway in the Pacific Northwest (Golden Years of Railroading). Waukesha, Wisconsin: Kalmbach Publishing. ISBN 0-89024-420-0.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Hidy, Ralph W. (2004). The Great Northern Railway: A History. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0-8166-4429-2.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Yenne, Bill (2005). Great Northern Empire Builder. St. Paul, Minnesota: MBI. ISBN 0-7603-1847-6.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Sherman, T. Gary, CONQUEST AND CATASTROPHE (The Triumph and Tragedy of the Great Northern Railway Through Stevens Pass), AuthorHouse, Bloomington, Indiana, 2004. ISBN 1-4184-9575-1

External links

- Great Northern Railway Company Records, Minnesota Historical Society.

- Great Northern Railway Historical Society

- The Great Northern Empire — Then and Now

- The Great Northern Railway

- Great Northern Railway Page

- Great Northern Railway Post Office Car No. 42 — photographs and short history of one of six streamlined baggage-mail cars built for the Great Northern by the American Car and Foundry Company in 1950.

- Burlington Northern Adventures: Railroading in the Days of the Caboose, written by former brakeman, conductor and trainmaster William J. Brotherton

- Great Northern History, photos and O gage model railroad.

- Great Northern Railway route map (1920)

- University of Washington Libraries: Digital Collections:

- Lee Pickett Photographs Over 900 photographs documenting scenes from Snohomish, King and Chelan Counties in Washington state from the early 1900s to the 1940s. Includes images of the Great Northern Railway.

- Transportation Photographs An ongoing digital collection of photographs depicting various modes of transportation in the Pacific Northwest region and Western United States during the first half of the 20th century. Includes images of the Great Northern Railway.

- The Truth About the "Robber Barons" A discussion of Hill's building of the transcontinental railroad by Thomas DiLorenzo

- Dutiful Son: Louis W. Hill Sr. Book, Book about Louis W. Hill Sr., son and successor of empire builder James J. Hill at Ramsey County Historical Society.

- "The Egotistigraphy", by John Sanford Barnes. An autobiography, including his role in the early financing of the Great Northern Railway and the career of James J. Hill, privately printed 1910. Internet edition edited by Susan Bainbridge Hay 2012

- Great Northern Railway (U.S.)

- Predecessors of the Burlington Northern Railroad

- Companies based in Saint Paul, Minnesota

- Defunct Idaho railroads

- Defunct Minnesota railroads

- Defunct Montana railroads

- Defunct North Dakota railroads

- Defunct Washington (state) railroads

- Defunct Wisconsin railroads

- Former Class I railroads in the United States

- Railway companies established in 1889

- Railway companies disestablished in 1970

- Defunct California railroads

- Defunct South Dakota railroads

- Defunct Iowa railroads

- Defunct Oregon railroads

- 1889 establishments in the United States