| Revision as of 19:11, 5 October 2013 edit88.104.219.76 (talk) No source. Probably tiny percentage← Previous edit | Revision as of 19:41, 5 October 2013 edit undo88.104.219.76 (talk) Not considered reliableNext edit → | ||

| Line 28: | Line 28: | ||

| ===The question of colonization and genocide in the Americas=== | ===The question of colonization and genocide in the Americas=== | ||

| Estimates of population decline in the Americas from the first contact with Europeans in 1492 until the turn of the 20th century depend on the estimation of the initial pre-contact population. In the early 20th century, scholars estimated low populations for the pre-contact Americas, with ]'s estimate as low as 8,4 million people in the entire hemisphere. Archaeological findings and a better overview of early censuses have contributed to much higher estimates |

Estimates of population decline in the Americas from the first contact with Europeans in 1492 until the turn of the 20th century depend on the estimation of the initial pre-contact population. In the early 20th century, scholars estimated low populations for the pre-contact Americas, with ]'s estimate as low as 8,4 million people in the entire hemisphere. Archaeological findings and a better overview of early censuses have contributed to much higher estimates. Denevan's estimate was 57,3 million.{{sfn|Thornton|1987|p=23}} Russell Thornton (1987) arrived at a figure around 70 million.{{sfn|Thornton|1987|p=25}} Depending on the estimate of the initial population, by 1900 the indigenous population can be said to have declined by more than 80%,{{cn|date=September 2013}} due mostly to the effects of diseases such as smallpox, measles and cholera. | ||

| Scholars who have argued prominently that this population decline can be considered genocidal include historian ]{{sfn|Stannard|1993}} and anthropological demographer ]{{sfn|Thornton|1987}}, as well as scholar activists such as ], ] and ]. Stannard compares the events of colonization that led to the population decline in the Americas with the definition of genocide in the 1948 UN convention, and writes that "In light of the U.N. language, even putting aside some of its looser constructions - it is impossible to know what transpired in the Americas during the sixteenth seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and not conclude that it was genocide".{{sfn|Stannard|1993|p=281}} Thornton does not consider the onslaught of disease to be genocide, and only describes as genocide the direct impact of warfare, violence and massacres, many of which had the effect of wiping out entire ethnic groups.{{sfn|Thornton|1987|pp=104-13}} ] scholar and political scientist ] rejects the label of genocide and views the depopulation of the Americas as "not a crime but a tragedy".<ref>{{cite web|author=Guenter Lewy |url=http://hnn.us/articles/7302.html |title= Were American Indians the Victims of Genocide? |publisher=History News Network |year=2007 |accessdate=2013-08-28}}</ref> | Scholars who have argued prominently that this population decline can be considered genocidal include historian ]{{sfn|Stannard|1993}} and anthropological demographer ]{{sfn|Thornton|1987}}, as well as scholar activists such as ], ] and ]. Stannard compares the events of colonization that led to the population decline in the Americas with the definition of genocide in the 1948 UN convention, and writes that "In light of the U.N. language, even putting aside some of its looser constructions - it is impossible to know what transpired in the Americas during the sixteenth seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and not conclude that it was genocide".{{sfn|Stannard|1993|p=281}} Thornton does not consider the onslaught of disease to be genocide, and only describes as genocide the direct impact of warfare, violence and massacres, many of which had the effect of wiping out entire ethnic groups.{{sfn|Thornton|1987|pp=104-13}} ] scholar and political scientist ] rejects the label of genocide and views the depopulation of the Americas as "not a crime but a tragedy".<ref>{{cite web|author=Guenter Lewy |url=http://hnn.us/articles/7302.html |title= Were American Indians the Victims of Genocide? |publisher=History News Network |year=2007 |accessdate=2013-08-28}}</ref> | ||

Revision as of 19:41, 5 October 2013

| Part of a series on |

| Genocide of indigenous peoples |

|---|

| Issues |

| Sub-Saharan Africa |

Americas (history)

|

| East, South, Southeast Asia |

| Europe and North Asia |

| Oceania |

| West Asia / North Africa |

| Related topics |

Genocide of indigenous peoples is the genocidal destruction of indigenous peoples, understood as ethnic minorities whose territory has been occupied by colonial expansion or the formation of a nation state, by a dominant political group such as a colonial power or a nation state.

While the concept of genocide was formulated by Raphael Lemkin in the mid-20th century, acts of genocidal violence against indigenous groups frequently occurred in the Americas, Australia, Africa and Asia with the expansion of various European colonial powers such as the Spanish and British empires, and the subsequent establishment of nation states on indigenous territory. According to Lemkin, colonization was in itself "intrinsically genocidal". He saw this genocide as a two-stage process, the first being the destruction of the indigenous population's way of life. In the second stage, the newcomers impose their way of life on the minority group. Imperial and colonial forms of genocide are enacted in two main ways, either through the deliberate clearing of territories of their original inhabitants in order to make them exploitable for purposes of resource extraction or colonial settlements, or through enlisting indigenous peoples as forced laborers in colonial or imperialist projects of resource extraction. The designation of specific events as genocidal is often controversial.

Some scholars, among them Lemkin, have argued that cultural genocide, sometimes called ethnocide, should also be recognized. A people may continue to exist, but are prevented from perpetuating their group identity by prohibitions against cultural and religious practices that are the basis of that identity. The accusation of cultural genocide carried out by the Chinese during the occupation of Tibet is an example.

Genocide debate

The concept of genocide was defined in 1944 by Raphael Lemkin. After World War II, it was adopted by the United Nations in 1948. For Lemkin, genocide was broadly defined and included all attempts to destroy a specific ethnic group, whether strictly physical through mass killings, or cultural or psychological through oppression and destruction of indigenous ways of life.

The UN definition, which is used in international law, is narrower than Lemkin's, and states that genocide is: "...any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such:

- (a) Killing members of the group;

- (b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

- (c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

- (d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

- (e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group."

Most attempts to define specific events as genocidal are disputed to various degrees, especially when the victims are minority groups such as indigenous peoples and the alleged perpetrator is a modern nation state rather than a colonial empire. In these cases, whether or not genocide occurred is a legal question to be settled in International human rights courts.

The determination of whether a historical event should be considered genocide can be a matter of scholarly debate. Because legal liability is not at issue, the UN definition may not always provide the basis for such discussions. Historians may draw on broader definitions such as Lemkin's, which sees colonialist violence against indigenous peoples as inherently genocidal. For example, in the case of the colonization of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas, when 90% of the indigenous population was wiped out in 500 years of European colonization, it can be debatable whether genocide occurs when disease was a major cause of population decline, since disease sometimes may be introduced deliberately, but more often without the intent to cause death. Some scholars argue that intent is not necessary, since genocide may be the cumulative result of minor conflicts in which settlers, or colonial or state agents, perpetrate violence against minority groups. Others argue that the dire consequences of European diseases among many New World populations were exacerbated by different forms of genocidal violence, and that intentional and unintentional deaths cannot easily be separated. Some scholars regard the colonization of the Americas as genocide, since it was largely achieved through systematically exploiting, removing and destroying specific ethnic groups, even when most deaths were caused by disease and not direct violence from colonizers. In this view, the concept of "manifest destiny" in the westward expansion from the eastern United States can be seen as contributing to genocide.

Pre-1948 examples

In the 16th century, the expansion of European empires led to the conquering of the Americas, Africa, Australasia and Asia. This period of expansion resulted in several instances of massacres, systematic annihilation, and genocide. Many indigenous peoples, such as the Yuki, Beothuk the Pallawah and Herero, were brought to the brink of extinction. In some cases, entire tribes were annihilated.

The expansionist policies of the Zulu under Shaka resulted in the deaths of up to one million people. By the middle of the 1840s, the "Great Crushing" brought about by Zulu expansionism had virtually depopulated the regions between the rivers of Thuleka and Mzimvubu.

The question of colonization and genocide in the Americas

Estimates of population decline in the Americas from the first contact with Europeans in 1492 until the turn of the 20th century depend on the estimation of the initial pre-contact population. In the early 20th century, scholars estimated low populations for the pre-contact Americas, with Alfred Kroeber's estimate as low as 8,4 million people in the entire hemisphere. Archaeological findings and a better overview of early censuses have contributed to much higher estimates. Denevan's estimate was 57,3 million. Russell Thornton (1987) arrived at a figure around 70 million. Depending on the estimate of the initial population, by 1900 the indigenous population can be said to have declined by more than 80%, due mostly to the effects of diseases such as smallpox, measles and cholera.

Scholars who have argued prominently that this population decline can be considered genocidal include historian David Stannard and anthropological demographer Russell Thornton, as well as scholar activists such as Vine Deloria, Jr., Russell Means and Ward Churchill. Stannard compares the events of colonization that led to the population decline in the Americas with the definition of genocide in the 1948 UN convention, and writes that "In light of the U.N. language, even putting aside some of its looser constructions - it is impossible to know what transpired in the Americas during the sixteenth seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and not conclude that it was genocide". Thornton does not consider the onslaught of disease to be genocide, and only describes as genocide the direct impact of warfare, violence and massacres, many of which had the effect of wiping out entire ethnic groups. Holocaust scholar and political scientist Guenter Lewy rejects the label of genocide and views the depopulation of the Americas as "not a crime but a tragedy".

Portuguese colonial expansion in Africa and Brazil

Some have argued that genocide occurred during the Portuguese colonization of the Americas, starting in 1549 by Pedro Álvares Cabral on the coast of what is now the country of Brazil. It has also been argued that genocide has occurred during the modern era with the ongoing destruction of the Jivaro, Yanomami and other tribes. Over 80 indigenous tribes disappeared between 1900 and 1957, and of a population of over one million during this period 80% had been killed through deculturalization, disease, or murder.

Spanish colonization of the Americas

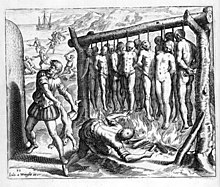

It is estimated that during the Spanish conquest of the Americas up to eight million indigenous people died, mainly through disease. Acts of brutality in the Caribbean and the systematic annihilation occurring on the Caribbean islands prompted Dominican friar Bartolomé de las Casas to write Brevísima relación de la destrucción de las Indias ("A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies") in 1552. Las Casas wrote that the indigenous population on the Spanish colony of Hispaniola had been reduced from 400,000 to 200 in a few decades. His works were among those that gave rise to the term Leyenda Negra (Black Legend) to describe anti-Spanish propaganda.

With the initial conquest of the Americas completed, the Spanish implemented the encomienda system. In theory, encomienda placed groups of indigenous peoples under Spanish oversight to foster cultural assimilation and conversion to Christianity, but in practice led to the legally sanctioned exploitation of natural resources and forced labor under brutal conditions with a high death rate. Though the Spaniards did not set out to exterminate the indigenous peoples, believing their numbers to be inexhaustible, their actions led to the annihilation of entire tribes such as the Arawak. In the 1760s, an expedition despatched to fortify California, led by Gaspar de Portolà and Junípero Serra, was marked by slavery, forced conversions and genocide through the introduction of disease.

British Empire

The British Empire has been accused of several genocides. The doctrine of terra nullius was used by the British to justify their seizure of territory in Australia and Tasmania. The death of the 3,000–15,000 Aboriginal Tasmanians has been called an act of genocide.

United States colonization and westward expansion

In the late 16th century, England, France, Spain and the Netherlands launched colonization efforts in the part of North America that is now the United States. The United States has not been legally admonished by the international community for genocidal acts against its indigenous population, but many commentators and academics argue that events such as The Trail of Tears, the Sand Creek Massacre and the Mendocino War were genocidal in nature. Some accounts of genocidal massacres, such as Ward Churchill's claim that the US Army distributed blankets infected with small pox to the Mandans at Fort Clark in 1837, have been shown to be false.

Indian Removal and the Trail of Tears

Main articles: Indian Removal and Trail of TearsFollowing the Indian Removal Act of 1830 the American government began forcibly relocating East Coast tribes across the Mississippi. The removal included many members of the Cherokee, Muscogee (Creek), Seminole, Chickasaw, and Choctaw nations, among others in the United States, from their homelands to Indian Territory in eastern sections of the present-day state of Oklahoma. About 2,500–6,000 died along the trail of tears. Historians such as David Stannard and Barbara Mann have argued that the army deliberately routed the march of the Cherokee to pass through the cholera epidemic of Vicksburg, although the prevalent view in the literature has been that the choice of this route was an unfortunate coincidence. Stannard estimates that during the forced removal from their homelands, following the Indian Removal Act signed into law by President Andrew Jackson in 1830, 8000 Cherokee died, about half the total population.

American Indian Wars

Main article: American Indian Wars

During the American Indian Wars, the American Army carried out a number of massacres and forced relocations of Indigenous peoples that are sometimes considered genocide. The Sand Creek Massacre, which caused outrage in its own time, has been called genocide. General John Chivington led a 700-man force of Colorado Territory militia in a massacre of 70–163 peaceful Cheyenne and Arapaho, about two-thirds of whom were women, children, and infants. Chivington and his men took scalps and other body parts as trophies, including human fetuses and male and female genitalia. In defense of his actions Chivington stated,

Damn any man who sympathizes with Indians! ... I have come to kill Indians, and believe it is right and honorable to use any means under God's heaven to kill Indians. ... Kill and scalp all, big and little; nits make lice.

— - Col. John Milton Chivington, U.S. Army

In 1867 General Philip Sheridan was appointed by President Grant to "pacify" the Indians of the plains. His approach was encapsulated in the saying "The only good Indian is a dead Indian", although he himself denied having said this when criticized by his political opponents.

Colonization of California and Oregon

The U.S. colonization of California started in earnest in 1849, and resulted in a large number of massacres by colonists against Indians in the territory, causing several entire ethnic groups to be wiped out. In one such series of conflicts, the so-called Mendocino War and the subsequent Round Valley War, the entire Yuki people was brought to the brink of extinction, from a previous population of some 3,500 people to fewer than 100. According to Russell Thornton, estimates of the pre-Columbian population of California was at least 310,000, and perhaps as much as 705,000. By 1849, due to Spanish colonization and epidemics this number had decreased to 100,000. But from 1849 and up until 1890 the Indigenous population of California had fallen below 20,000, primarily because of the killings.

Colonization of Australia, New Zealand and Tasmania

Main article: Australian genocide debateThe extinction of the Tasmanian Aborigines is regarded as a classic case of genocide by Lemkin, most comparative scholars of genocide, and many general historians, including Robert Hughes, Ward Churchill, Leo Kuper and Jared Diamond, who base their analysis on previously published histories. Between 1824 and 1908 White settlers in Queensland killed more than 10,000 Aborigines, who were regarded as vermin and sometimes even hunted for sport.

Ben Kiernan, an Australian historian of genocide, treats the Australian evidence over the first century of colonization as an example of genocide in his 2007 history of the concept and practice, Blood and soil: a world history of genocide and extermination from Sparta to Darfur. The Australian practice of removing the children of Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent from their families, has been described as genocidal. The 1997 report "Bringing them Home" concluded that the forced separation of Aboriginal children from their family constituted an act of genocide. In the 1990s a number of Australian state institutions, including the state of Queensland, apologized for its policies regarding forcible separation of aboriginal children. Another allegation against the Australian state is the use of medical services to Aboriginals to administer contraceptive therapy to aboriginal women without their knowledge or consent, including the use of Depo Provera, as well as tubal ligations. Both forced adoption and forced contraception would fall under the provisions of the UN genocide convention. Many Australian politicians and scholars, including historian Geoffrey Blainey, political scientist Ken Minogue and prominently professor Keith Windschuttle, reject the view that Australian aboriginal policy was genocidal.

Rubber Boom in Congo and Putumayo

From 1879 to 1912, the world experienced a rubber boom. Rubber prices skyrocketed, and it became increasingly profitable to extract rubber from rainforest zones in South America and Central Africa. Rubber extraction was labor intensive, and the need for a large workforce had a significant negative effect on the indigenous population across Brazil, Peru, Ecuador and Columbia and in the Congo. The owners of the plantations or rubber barons were rich, but those who collected the rubber made very little, as a large amount of rubber was needed to be profitable. Rubber barons rounded up all the Indians and forced them to tap rubber out of the trees. Slavery and gross human rights abuses were widespread, and in some areas 90% of the Indian population was wiped out. One plantation started with 50,000 Indians and when the killings were discovered, only 8,000 were still alive. These rubber plantations were part of the Brazilian rubber market which declined as rubber plantations in Southeast Asia became more effective.

Roger Casement, an Irishman travelling the Putumayo region of Peru as a British consul during 1910-1911, documented the abuse, slavery, murder and use of stocks for torture against the native Indians:

"The crimes charged against many men now in the employ of the Peruvian Amazon Company are of the most atrocious kind, including murder, violation, and constant flogging."

Congo Free State

Main article: Congo Free StateUnder Leopold II of Belgium the population loss in the Congo Free State is estimated at sixty percent.

Herero and Namaqua genocide

Main article: Herero and Namaqua GenocideThe mass killings and extreme violence against the indigenous African population by the German colonial empire can be dated to the earliest German settlements on the continent. It was reported that, between 1885 and 1918, the indigenous population in German South-West Africa (GSWA), Togo, German East Africa (GEA) and the Cameroons suffered from various human rights abuses including genocide, starvation, forced relocation for use as labour and of being incarcerated in concentration camps. The German Empire also carried out atrocities in their colonies in Samoa and New Guinea. The German Empire's action in GSWA against the Herero tribe is considered by Howard Ball to be the first genocide of the 20th century. After the Herero, Namaqua and Damara began an uprising against the colonial government, General Lothar von Trotha, appointed as head of the German forces in GSWA by Emperor Wilhelm II in 1904, gave the order for the German forces to push them into the desert where they would die. In 2004, the German state apologised for the genocide. While many argue that the military campaign in Tanzania to suppress the Maji Maji Rebellion in GEA between 1905 and 1907 was not an act of genocide, as the military did not have as an intentional goal the deaths of hundreds of thousands of Africans, according to Dominik J. Schaller, the statement released at the time by Governor Gustav Adolf von Götzen did not exculpate him from the charge of genocide, but was proof that the German administration knew that their scorched earth methods would result in famine. It is estimated that 200,000 Africans died from famine with some areas completely and permanently devoid of human life.

Contemporary examples

The genocide of indigenous tribes is still an ongoing feature in the modern world, given examples such as in Brazil, with the ongoing destruction of the Jivaro, Yanomami and other tribes. The states actions in Bangladesh, against the Jumma have been described internationally as ethnic cleansing and genocide. Paraguay has also been accused of carrying out a genocide against the Aché whose case was brought before the Inter-American Human Rights Commission. The commission gave a provisional ruling that genocide had not been committed by the state, but did express concern over "possible abuses by private persons in remote areas of the territory of Paraguay."

Bangladesh

Main article: Persecution_of_indigenous_peoples_in_BangladeshIn Bangladesh, the persecution of the indigenous tribes of the Chittagong Hill Tracts such as the Chakma, Marma, Tripura and others who are mainly Buddhists, Hindus, Christians, and Animists, has been described as genocidal. The Chittagong Hill Tracts are located bordering India, Myanmar and the Bay of Bengal, and is the home to 500,000 indigenous people. The perpetrators of are the Bangladeshi military and the Bengali Muslim settlers, who together have burned down Buddhist and Hindu temples, killed many Chakmas, and carried out a policy of gang-rape against the indigenous people. There are also accusations of Chakmas being forced to convert to Islam, many of them children who have been abducted for this purpose. The conflict started soon after Bangladeshi independence in 1972 when the Constitution imposed Bengali as the sole official language, Islam as the state religion - with no cultural or linguistic rights to minority populations. Subsequently the government encouraged and sponsored massive settlement by Bangladeshis in region, which changed the demographics from 98 percent indigenous in 1971 to fifty percent by 2000. The government allocated a full third of the Bangladeshi military to the region to support the settlers, sparking a protracted guerilla war between Hill tribes and the military. During this conflict which officially ended in 1997, and in the subsequent period, a large number of human rights violations against the indigenous peoples have been reported, with violence against indigenous women being particularly extreme.

Brazil

Main article: Genocide of indigenous peoples in BrazilIn the late 1950s until 1968, the state of Brazil submitted their indigenous peoples of Brazil to violent attempts to integrate, pacify and acculturate their communities. In 1967 public prosecutor Jader de Figueiredo Correia, submitted the Figueiredo Report to the dictatorship which was then ruling the country, the report which ran to seven thousand pages was not released until 2013. The report documents genocidal crimes against the indigenous peoples of Brazil, including mass murder, torture and bacteriological and chemical warfare, reported slavery, and sexual abuse The rediscovered documents are being examined by the National Truth Commission who have been tasked with the investigations of human rights violations which occurred in the periods 1947 through to 1988. The report reveals that the IPS had enslaved indigenous people, tortured children and stolen land. The Truth Commission is of the opinion that entire tribes in Maranhão were completely eradicated and in Mato Grosso, an attack on thirty Cinturão Largo left only two survivors. The report also states that landowners and members of the IPS had entered isolated villages and deliberately introduced smallpox. Of the one hundred and thirty four people accused in the report the state has as yet not tried a single one. The report also detailed instances of mass killings, rapes and torture, Figueiredo stated that the actions of the IPS had left the indigenous peoples near extinction. The state abolished the IPS following the release of the report. The Red Cross launched an investigation after further allegations of ethnic cleansing were made after the IPS had been replaced.

Colombia

In the protracted conflict in Colombia, indigenous groups such as the Awá, Wayuu, Pijao and Paez people have become subjected to intense violence by right-wing paramilitaries, leftist guerrillas, and the Colombian army. Drug cartels, international resource extraction companies and the military also use violence to force the indigenous groups out of their territories. The National Indigenous Organization of Colombia argues that the violence is genocidal in nature, but others question whether there is a "genocidal intent" as required in international law.

Congo (DRC)

In the Democratic Republic of Congo genocidal violence against the indigenous Mbuti, Lese and Ituri peoples has been endemic for decades. During the Congo Civil War (1998–2003), Pygmies were hunted down and eaten by both sides in the conflict, who regarded them as subhuman. Sinafasi Makelo, a representative of Mbuti pygmies, has asked the UN Security Council to recognize cannibalism as a crime against humanity and also as an act of genocide. According to a report by Minority Rights Group International there is evidence of mass killings, cannibalism and rape. The report, which labeled these events as a campaign of extermination, linked much of the violence to beliefs about special powers held by the Bambuti. In Ituri district, rebel forces ran an operation code-named "Effacer le tableau" (to wipe the slate clean). The aim of the operation, according to witnesses, was to rid the forest of pygmies.

East Timor

| This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (August 2013) |

Guatemala

During the Guatemalan Civil War (1960 - 1996) the state forces carried out violent atrocities against the Maya. The government considered the Maya to be aligned with the communist insurgents, which they sometimes were but often were not. Guatemalan armed forces carried out three genocidal campaigns. The first was a scorched earth policy which was also accompanied by mass killing, including the forced conscription of Mayan boys into the military where they were sometimes forced to participate in massacres against their own home villages. The second was to hunt down and exterminate those who had survived and evaded the army and the third was the forced relocation of survivors to "reeducation centers" and the continued pursuit of those who had fled into the mountains. The armed forces used genocidal rape of women and children as a deliberate tactic. Children were bludgeoned to death by beating them against walls or thrown alive into mass graves were they would be crushed by the weight of the adult dead thrown atop them. An estimated 200,000 people, most of them Maya, disappeared during the Guatemalan Civil War. After the 1996 peace accords a legal process was begun to determine the legal responsibility of the atrocities, and to locate and identify the disappeared. In 2013 former president Efraín Ríos Montt was convicted of genocide and crimes against humanity, and was sentenced to 80 years imprisonment. Ten days later, the Constitutional Court of Guatemala overturned the conviction.

Irian Jaya/West Papua

From the time of its independence until the late 1960s, the Indonesian government sought control of the Western half of the island of New Guinea, the area called Irian Jaya or West Papua, which had remained under the control of the Netherlands. When it finally achieved internationally recognized control of the area, a number of clashes occurred between the Indonesian government and the Free Papua Movement. The government of Indonesia began a series of measures aimed to suppress the organization in the 1970s and the suppression reached high levels in the mid-1980s. The resulting human rights abuses included extrajudicial killings, torture, disappearances, rape, and harassment of indigenous people throughout the province. A 2004 report by the Allard K. Lowenstein International Human Rights Clinic at Yale Law School identified both the mass violence and the transmigration policies which encouraged Balinese and Javanese families to relocate to the area as strong evidence "that the Indonesian government has committed proscribed acts with the intent to destroy the West Papuans as such, in violation of the 1948 Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide." Genocide against indigenous people in the region were key claims made in the U.S. case of Beanal v. Freeport, one of the first lawsuits where indigenous people outside the U.S. petitioned to get a ruling against a multinational corporation for environmental destruction outside of the U.S. While the petitioner, an indigenous leader, claimed that the mining company Freeport-McMoRan had committed genocide through environmental destruction which "resulted in the purposeful, deliberate, contrived and planned demise of a culture of indigenous people," the court found that genocide pertains only to destruction of indigenous people and did not apply to the destruction of the culture of indigenous people; however, the court did leave open the opportunity for the petitioners to amend their filings with additional claim.

Myanmar

In Myanmar (Burma), the long running civil war between the Military Junta and the insurgents has resulted in widespread genocidal atrocities against the indigenous Karen people some of whom are allied with the insurgents. Burmese General Maung Hla stated that one day Karen would only exist "in a museum" The government has deployed 50 battalions in the Northern sector systematically attacking Karen villages with mortar and machine gun fire, and landmines. At least 446,000 Karen have been displaced from their homes by the military. Karen are also reported to have been be subjected to forced labor, genocidal rape, child labor and the conscription of child soldiers.

Paraguay

There are 17 indigenous tribes who live primarily in the Chaco region of Paraguay. In 2002, their numbers were estimated at 86,000. During the period between 1954 and 1989, when the military dictatorship of General Alfredo Stroessner ruled Paraguay, the indigenous population of the country suffered from more loss of territory and human rights abuses than at any other time in the nation's history. In early 1970, international groups claimed that the state was complicit in the genocide of the Aché, with charges ranging from kidnapping and the sale of children, withholding medicines and food, slavery and torture. During the 1960s and 1970s, 85% of the Aché tribe died, often hacked to death with machetes, in order to make room for the timber industry, mining, farming and ranchers. According to Jérémie Gilbert, the situation in Paraguay has proven that it is difficult to provide the proof required to show "specific intent", in support of a claim that genocide had occurred. The Aché, whose cultural group is now seen as extinct, fell victim to development by the state who had promoted the exploration of their territories by transnational companies for natural resources. Gilbert concludes that although a planned and voluntary destruction had occurred, it is argued by the state that there was no intent to destroy the Aché, as what had happened was due to development and was not a deliberate action.

Phillipines

| This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (August 2013) |

Footnotes

- The definition of "indigenous peoples", is controversial. This article uses a definition of "indigenous peoples" similar to used by international legislation by UN, UNESCO, ILO and WTO, as well as by the majority of relevant scholarship which applies to those ethnic minorities that were indigenous to a territory prior to being incorporated into a national state, and who are politically and culturally separate from the majority ethnic identity of the state that they are a part of. This definition differs from the commonsense definition of indigenous peoples as being simply the first known inhabitants of a territory.

- By 'genocide' we mean the destruction of an ethnic group . . . . Generally speaking, genocide does not necessarily mean the immediate destruction of a nation, except when accomplished by mass killings of all members of a nation. It is intended rather to signify a coordinated plan of different actions aiming at the destruction of essential foundations of the life of national groups, with the aim of annihilating the groups themselves. The objectives of such a plan would be disintegration of the political and social institutions, of culture, language, national feelings, religion, and the economic existence of national groups, and the destruction of the personal security, liberty, health, dignity, and even the lives of the individuals belonging to such groups.

- "As in all wars against uncivilized nations the systematic damage to hostile people's goods and chattels was indispensable in this case. The destruction of economic values like the burning of villages and food supplies might seem barbaric. It one considers, however, on the one hand, in what short time African Negro huts are erected anew and the luxuriant growth of tropic nature gives rise to new field crops, and on the other hand the subjection of the enemy was only possible through a procedure like this, then one will consequently take a more favourable view of this dira necessitas."

References

- ^ Maybury-Lewis 2002, p. 45.

- Jones 2010, p. 139.

- Forge 2012, p. 77.

- Moses 2004, p. 27.

- Maybury-Lewis 2002, p. 48.

- Hitchcock & Koperski 2008, pp. 577–82.

- Mehta 2008, p. 19.

- Attar 2010, p. 20.

- Sautman 2003, pp. 174–240.

- Lemkin 2008, p. 79.

- Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, Article 2

- Cave 2008, p. 273-74.

- Barkan 2003.

- Jones 2010, p. 67.

- Smithers 2013, p. 3.

- Byrd 2011, p. 7.

- Totten 2007, p. 28.

- ^ Gump 1994, p. 47.

- Levene 2005, p. 146.

- Thornton 1987, p. 23.

- Thornton 1987, p. 25.

- Stannard 1993.

- Thornton 1987.

- Stannard 1993, p. 281.

- Thornton 1987, pp. 104–13.

- Guenter Lewy (2007). "Were American Indians the Victims of Genocide?". History News Network. Retrieved 2013-08-28.

- ^ Churchill 2000, p. 433.

- ^ Scherrer 2003, p. 294.

- Hinton 2002, p. 57.

- Forsythe 2009, p. 297.

- Juang 2008, p. 510.

- Maybury-Lewis 2002, p. 44.

- Grenke 2005, p. 200.

- Trafzer 1999, p. 1816.

- Gigoux 2011, p. 305.

- Madley 2004, p. 167–192.

- Reynolds 2004, p. 127.

- Richard Middleton and Anne Lombard, Colonial America: A History to 1763 (4th ed. 2011) p. 23

- Martin 2004, pp. 740–746.

- Brown 2006.

- Baird 1973.

- ^ Stannard 1993, p. 124.

- Mann 2009.

- United States Congress Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, 1865 (testimonies and report)

- Brown, Dee (2001) . "War Comes to the Cheyenne". Bury my heart at Wounded Knee. Macmillian. pp. 86–87. ISBN 978-0-8050-6634-0.

- Hutton, Paul Andrew. 1999. Phil Sheridan and His Army. p. 180

- Thornton 1987, pp. 107=109.

- Henry Reynolds, 'Genocide in Tasmania?', in A. Dirk Moses (ed.) Genocide and settler society: frontier violence and stolen indigenous children in Australian history, Berghahn Books, 2004 p.128.

- Tatz 2006, p. 125.

- Kiernan 2007, pp. 249–309.

- ^ Tatz 2006.

- Moses 2004.

- Tatz 2006, p. 128.

- Tatz 2006, pp. 130–31.

- Tatz 2006, p. 127.

- "Why do they hide?". Survival International. Retrieved 2013-08-27.

- "Horrific treatment of Amazon Indians exposed 100 years ago today". Survival International. Retrieved 2013-08-27.

- Hinton 2002, p. 47.

- Sarkin-Hughes 2011, p. 103.

- Ball 2011, p. 17.

- Sarkin-Hughes 2011, p. 3.

- Weiser 2008, p. 24.

- Meldrum 2004.

- Schaller 2010, pp. 309–310.

- The Cambridge History of Africa (1986), ed. J. D. Fage and R. Oliver

- Hull 2003, p. 161.

- Sarkin-Hughes 2011, p. 104.

- Arens 2010, p. 123.

- Jonassohn 1998, p. 257.

- Begovich 2007, p. 166.

- Quigley 2006, p. 125.

- Gray 1994.

- ^ O'Brien 2004.

- Mey 1984.

- Moshin 2003.

- Roy 2000.

- Chakma & Hill 2013.

- Watts 2013.

- Garfield 2001, p. 143.

- Warren 2001, p. 84.

- Jackson 2009.

- Jackson 2002.

- "Update 2011 - Colombia". Iwgia.org. Retrieved 2013-08-27.

- Pedro García Hierro. 2008. Colombia: The Case of the Naya. IWGIA Report 2

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (2012-10-18). "UNHCR report on Indigenous peoples in Colombia". Unhcr.org. Retrieved 2013-08-27.

- March 16, 2013 (2013-03-16). "Situation of Human Rights of Indigenous Peoples in Colombia". Hrbrief.org. Retrieved 2013-08-27.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - User Name: Brandon Barrett (2012-04-27). "Indigenous leader accuses Colombian govt of genocide Colombia News | Colombia Reports - Colombia News | Colombia Reports". Colombiareports.co. Retrieved 2013-08-27.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - Altshuler 2011, p. 636.

- BBC News 2003.

- "DR Congo Pygmies 'exterminated'". BBC News. 2004-07-06. Retrieved 2013-08-27.

- "Pygmies today in Africa". Irinnews.org. Retrieved 2013-08-27.

- rebels 'eating pygmies'

- ^ Hitchcock & Koperski 2008, p. 589.

- Sanford 2008, p. 545.

- Franco 2013, p. 80.

- Will Grant (2013-05-11). "BBC News - Guatemala's Rios Montt found guilty of genocide". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2013-08-27.

- Reuters (May 20, 2013). "Guatemala's top court annuls Rios Montt genocide conviction".

{{cite news}}:|last=has generic name (help) - "Ríos Montt genocide case collapses". The Guardian. May 20, 2013.

- Vickers 2013, p. 142.

- Premdas 1985, pp. 1056–1058.

- Lowenstein Clinic report 2004, p. 71.

- Lowenstein Clinic report 2004, p. 75.

- Khokhryakova 1998, p. 475.

- ^ Milbrandt 2012.

- "KNU President Saw Tamla Baw says peace needs a 1,000 more steps « Karen News". Karennews.org. 2012-02-02. Retrieved 2013-08-27.

- Rogers 2004.

- "Burma". World Without Genocide. 2010-11-09. Retrieved 2013-08-27.

- MRGI 2007, p. MRGI.

- Gilbert 2006, p. 118.

- Hitchcock & Koperski 2008, pp. 592–3.

Bibliography

- Allard K. Lowenstein International Human Rights Clinic, Yale Law School (2004). "Indonesian Human Rights Abuses in West Papua: Application of the Law of Genocide to the History of Indonesian Control" (PDF). Retrieved 5 September 2013.

- Altshuler, Alex (2011). K. Bradley Penuel, Matt Statler (ed.). Encyclopedia of Disaster Relief,. SAGE. ISBN 978-1412971010.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Arens, Jenneke (2010). "Genocide in the Chittagong Hills Tracts, Bangladesh". In Samuel Totten, Robert K. Hitchcock (ed.). Genocide of indigenous Peoples. Transaction. pp. 117–142. ISBN 978-1412814959.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Attar, Samar (2010). Debunking the Myths of Colonization: The Arabs and Europe. University Press Of America. ISBN 978-0761850380.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Bischoping, K.; Fingerhut, N (1996). "Border Lines: Indigenous Peoples in Genocide Studies". Canadian Review of Sociology/Revue canadienne de sociologie. 33 (4): 481–506.

- Brown, Thomas (2006). "Did the U.S. Army Distribute Smallpox Blankets to Indians? Fabrication and Falsification in Ward Churchill's Genocide Rhetoric". University of Michigan.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link)

- "DR Congo Pygmies appeal to UN". BBC News. 23 May, 2003. Retrieved 2013-08-27.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)

- Barkan, Elazar (2003). "Genocide of indigenous peoples". The Specter of Genocide: Mass Murder in Historical Perspective. Cambridge University Press. pp. 117–140. ISBN 978-0521527507.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Ball, Howard (2011). "Early 20th-Century "Genocides"". Genocide : a reference handbook. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-488-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Baird, David (1973). "The Choctaws Meet the Americans, 1783 to 1843". The Choctaw People. United States: Indian Tribal Series. p. 36. LCCN 73-80708.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Begovich, Milica (2007). Karl R. DeRouen, Uk Heo (ed.). Civil Wars of the World. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1851099191.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Byrd, Jodi A. (2011). The Transit of Empire: Indigenous Critiques of Colonialism. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0816676408.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Cave, Alfred A. (2008). "Genocide in the Americas". In Dan Stone (ed.). The Historiography of Genocide. Palgrave MAcMillan. pp. 273–296.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Chakma, Kabita; Hill, Glen (2013). "Indigenous Women and Culture in the Colonized Chittagong Hills Tracts of Bangladesh". In Kamala Visweswaran (ed.). Everyday Occupations: Experiencing Militarism in South Asia and the Middle East. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 132–157. ISBN 978-0812244878.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Churchill, Ward (2000). Israel W. Charny (ed.). Encyclopedia of Genocide. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0874369281.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Franco, Jean (2013). Cruel Modernity. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0822354567.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Forsythe, David P. (2009). Encyclopedia of Human Rights, Volume 1. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195334029.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Forge, John (2012). Designed to Kill: The Case Against Weapons Research. Springer. ISBN 978-9400757356.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Gigoux, Carlos (2011). "Globalization and indigenous peoples". In Bryan S. Turner (ed.). The Routledge International Handbook of Globalization Studies. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415686082.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

- Gilbert, Jérémie (2006). Indigenous Peoples' Land Rights Under International Law: From Victims to Actors. Transnational. ISBN 978-1571053695.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Gray, Richard A. (1994). "Genocide in the Chittagong Hill tracts of Bangladesh". Reference Services Review. 22 (4): 59–79.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Gump, James O. (1994). The Dust Rose Like Smoke: The Subjugation of the Zulu and the Sioux. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0803270596.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Grenke, Arthur (2005). God, Greed, and Genocide: The Holocaust Through the Centuries. New Academia Publishing. ISBN 978-0976704201.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Hull, Isabel V. (2003). Robert Gellately, Ben Kiernan (ed.). The Specter of Genocide: Mass Murder in Historical Perspective. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521527507.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Hitchcock, Robert K.; Koperski, Thomas E. (2008). "Genocides against Indigenous peoples". In Dan Stone (ed.). The Historiography of Genocide. Palgrave MAcMillan. pp. 577–618.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Hinton, Alexander L. (2002). Annihilating Difference: The Anthropology of Genocide. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520230293.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Jackson, Jean E. (2009). The Awá of Southern Colombia: a "Perfect Storm" of Violence (PDF). Report to the AAA Committee for Human Rights.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Jackson, Jean E. (2002). "Caught in the Crossfire: Colombia's indigenous peoples during the 1990s.". In David Maybury-Lewis (ed.). Identities in Conflict: Indigenous peoples and Latin American States (PDF). Harvard University Press. pp. 107–134.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Juang, Richard (2008). Richard M. Juang, Noelle Morrissette (ed.). Africa and the Americas: Culture, Politics, and History. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1851094417.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

- Jones, Adam (2010). "3. Genocides of Indigenous Peoples". Genocide: A Comprehensive Introduction (2nd ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-0415486187.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Jonassohn, Kurt (1998). Genocide and Gross Human Rights Violations: In Comparative Perspective. Transaction. ISBN 1560003146.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

- Khokhryakova, Anastasia (1998). "Beanal v. Freeport-McMoRan, Inc: Liability of a Private Actor for an International Environmental Tort under the Alien Tort Claims Act". Colorado Journal of International Environmental Law and Policy. 9: 463–493.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Kiernan, Ben (2007), Blood and Soil: A World History of Genocide and Extermination from Sparta to Darfur, Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-10098-3

- Lemkin, Raphael (2008). Axis Rule in Occupied Europe. The Lawbook Exchange. ISBN 978-1584779018.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Levene, Mark (2005). Genocide in the Age of the Nation State: Meaning of Genocide v. 1: The Meaning of Genocide. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1850437529.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Mann, Barbara Alice (2009). The Tainted Gift: The Disease Method of Frontier Expansion. ABC Clio.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Martin, Stacie E (2004). "Native Americans". In Dinah Shelton (ed.). Encyclopedia of Genocide and Crimes against Humanity. Macmillan Library Reference. pp. 740–746.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Meldrum, Andrew (16 August 2004). "German minister says sorry for genocide in Namibia". The Guardian.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link)

- Milbrandt, Jay (2012). "Tracking Genocide: Persecution of the Karen in Burma". Texas International Law Journal.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Mey, Wolfgang, ed. (1984). Genocide in the Chittagong Hill Tracts, Bangladesh. Copenhagen: International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs (IWGIA).

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Moshin, A. (2003). The Chittagong Hill Tracts, Bangladesh: On the Difficult Road to Peace. Boulder, Col.: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Madley, Benjamin (2004). "Patterns of frontier genocide 1803–1910: the Aboriginal Tasmanians, the Yuki of California, and the Herero of Namibia" (PDF). Journal of Genocide Research. 6 (2).

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Moses, A. Dirk (2004). A. Dirk Moses (ed.). Genocide and Settler Society: Frontier Violence and Stolen Indigenous Children in Australian History. Berghahn. ISBN 978-1571814104.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Maybury-Lewis, David (2002). "Genocide against Indigenous peoples". Annihilating Difference: The Anthropology of Genocide. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520230293.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- MRGI, MRGI (2007). "World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples - Paraguay : Overview". Minority Rights Group International.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Nunpa, Chris Mato (2009). "A Sweet-Smelling Sacrifice". In Steven L. Jacobs (ed.). Confronting Genocide: Judaism, Christianity, Islam. Lexington. ISBN 978-0739135891.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- O'Brien, Sharon (2004). "The Chittagong Hill Tracts". In Dinah Shelton (ed.). Encyclopedia of Genocide and Crimes against Humanity. Macmillan Library Reference. pp. 176–177.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Premdas, Ralph R. (1985). "The Organisasi Papua Merdeka in Irian Jaya: Continuity and Change in Papua New Guinea's Relations with Indonesia". Asian Survey. 25 (10): 1055–1074.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Garfield, Seth (2001). Indigenous Struggle at the Heart of Brazil: State Policy, Frontier Expansion and the Xavante Indians, 1937-1988. Duke University Press. p. 143. ISBN 978-0822326656.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Quigley, John B. (2006). The Genocide Convention: An International Law Analysis. Ashgate. ISBN 978-0754647300.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Reynolds, Henry (2004). "Genocide in Tasmania?". In A. Dirk Moses (ed.). Genocide and Settler Society: Frontier Violence and Stolen Indigenous Children in Australian History. Berghahn. ISBN 978-1571814104.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Roy, Rajkumari (2000). Land Rights of the Indigenous Peoples of the Chittagong Hill Tracts, Bangladesh. Copenhagen: International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Rogers, Benedict (2004). A Land without Evil: Stopping the Genocide of Burma's Karen People. Monarch Books.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Sautman, Barry (2003). "Cultural genocide and Tibet" (PDF). Tex. Int'l LJ. 38 (173–240).

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Sanford, Victoria (2008). "¡Si hubo genocidio en Guatemala! Yes! There was genocide in Guatemala". In Dan Stone (ed.). The Historiography of Genocide. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 543–571. ISBN 978-0230279551.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Smithers, Gregory D. (2013). Donald Bloxham, A. Dirk Moses (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Genocide Studies. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199677917.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Scherrer, Christian P. (2003). Ethnicity Nationalism and Violence: Conflict Management, Human Rights and Multilateral Regimes. Ashgate. ISBN 978-0754609568.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Sarkin-Hughes, Jeremy (2011). Germany's Genocide of the Herero: Kaiser Wilhelm II, His General, His Settlers, His Soldiers. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 978-1847010322.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Schaller, Dominik J. (2010). "13". In A. Dirk Moses (ed.). Empire, Colony, Genocide: Conquest, Occupation, and Subaltern Resistance in World History. Berghahn. ISBN 978-1845457198.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Stannard, David E. (1993). American Holocaust:The Conquest of the New World: The Conquest of the New World. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 978-0-19-508557-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Tatz, Colin (2006). "8. Confronting Australian Genocide". In Roger Maaka, Chris Andersen (ed.). The Indigenous Experience: Global Perspectives. Canadian Scholars Press. ISBN 978-1551303000.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Thornton, Russel (1987). American Indian Holocaust and Survival: ˜a Population History Since 1492. Norman : University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-2074-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Trafzer, Clifford E. (1999). "Introduction". In Clifford E. Trafzer, Joel R. Hyer (ed.). Exterminate Them: Written Accounts of the Murder, Rape, and Enslavement of Native Americans During the California Goldrush. Michigan State University. ISBN 978-0870135019.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Totten, Samuel (2007). Dictionary of Genocide: A-L. Greenwood. ISBN 978-0313329678.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

- Vickers, Adrian (2013). A History of Modern Indonesia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-01947-8. Retrieved 5 September 2013.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Warren, Jonathan W. (2001). Racial Revolutions: Antiracism and Indian Resurgence in Brazil. Duke University Press. p. 84. ISBN 978-0822327417.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Weiser, Martin (2008). The Herero War - the First Genocide of the 20th Century?. GRIN Verlag. ISBN 978-3638946285.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Watts, Jonathan; Jan Rocha (19 May 2013). "Brazil's 'lost report' into genocide surfaces after 40 years". The Guardian.