| Revision as of 15:00, 31 January 2014 edit173.12.50.13 (talk) →PhysicsTag: section blanking← Previous edit | Revision as of 15:00, 31 January 2014 edit undo50.201.134.58 (talk) →Conductor materialsTag: Possible vandalismNext edit → | ||

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

| Another situation for which this formula is not exact is with ] (AC), because the ] inhibits current flow near the center of the conductor. Then, the ''geometrical'' cross-section is different from the ''effective'' cross-section in which current is actually flowing, so the resistance is higher than expected. Similarly, if two conductors are near each other carrying AC current, their resistances will increase due to the ]. At ], these effects are significant for large conductors carrying large currents, such as ]s in an ],<ref>Fink and Beaty, ''Standard Handbook for Electrical Engineers 11th Edition'', pages 17–19</ref> or large power cables carrying more than a few hundred amperes. | Another situation for which this formula is not exact is with ] (AC), because the ] inhibits current flow near the center of the conductor. Then, the ''geometrical'' cross-section is different from the ''effective'' cross-section in which current is actually flowing, so the resistance is higher than expected. Similarly, if two conductors are near each other carrying AC current, their resistances will increase due to the ]. At ], these effects are significant for large conductors carrying large currents, such as ]s in an ],<ref>Fink and Beaty, ''Standard Handbook for Electrical Engineers 11th Edition'', pages 17–19</ref> or large power cables carrying more than a few hundred amperes. | ||

| \ | |||

| ==Conductor materials== | |||

| {{main|Electrical_resistivity_and_conductivity#Resistivity_of_various_materials}} | |||

| {{further2|]|]}} | |||

| Conduction materials include ]s, ]s, ]s, ]s, ]s and some nonmetallic conductors such as ] and ]s. | |||

| ] has a high ]. ] copper is the international standard to which all other electrical conductors are compared. The main grade of copper used for electrical applications, such as building wire, ] windings, cables and ]s, is ] (CW004A or ] designation C100140). This copper has an electrical conductivity of at least 101% IACS (International Annealed Copper Standard). If high conductivity copper needs to be ] or ]d or used in a reducing atmosphere, then ] (CW008A or ASTM designation C10100) may be used.<ref>High conductivity coppers (electrical), Copper Development Association (U.K.), http://www.copperinfo.co.uk/alloys/copper/</ref> Because of its ease of connection by ] or clamping, copper is still the most common choice for most light-gauge wires. | |||

| ] is more conductive than copper, but due to cost it is not practical in most cases. However, it is used in specialized equipment, such as ]s, and as a thin plating to mitigate ] losses at high frequencies. | |||

| ] wire, which has 61% of the conductivity of copper, has been used in building wiring for its lower cost. By weight, aluminum has higher conductivity than copper, but it has properties that cause problems when used for building wiring. It forms a resistive oxide within connections, causing terminals of wiring devices to heat. Aluminum can "creep", slowly deforming under load, eventually causing device connections to loosen, and also has a different ] compared to the materials used for connections. This accelerates the loosening of connections. These effects can be avoided by using wiring devices approved for use with aluminum. | |||

| Aluminum wires used for low voltage distribution, such as buried cables and service drops, require use of compatible connectors and installation methods to prevent heating at joints. Aluminum is also the most common metal used in high-voltage transmission lines, in combination with steel as structural reinforcement. | |||

| ] surfaces are not conductive. This affects the design of electrical enclosures that require the enclosure to be electrically connected. | |||

| Organic compounds such as octane, which has 8 carbon atoms and 18 hydrogen atoms, cannot conduct electricity. Oils are hydrocarbons, since | |||

| carbon has the property of tetracovalency and forms covalent bonds with other elements such as hydrogen, since it does not lose or gain electrons, thus does not form ions. Covalent bonds are simply the sharing of electrons. Hence, there is no separation of ions when electricity is passed through it. So the liquid (oil or any organic compound) cannot conduct electricity. | |||

| ==Conductor ampacity== | ==Conductor ampacity== | ||

Revision as of 15:00, 31 January 2014

| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Electrical conductor" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (January 2009) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

In physics and electrical engineering, a conductor is an object or type of material which permits the flow of electric charges in one or more directions. For example, a wire is an electrical conductor that can carry electricity along its length.

In metals such as copper or aluminum, the movable charged particles are electrons. Positive charges may also be mobile, such as the cationic electrolyte(s) of a battery, or the mobile protons of the proton conductor of a fuel cell. Insulators are non-conducting materials with few mobile charges and which support only insignificant electric currents.

Wire size

Wires are measured by their cross section. In many countries, the size is expressed in square millimeters. In North America conductors are measured by American wire gauge for smaller ones, and circular mils for larger ones.

Conductance

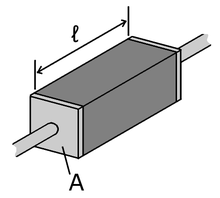

The resistance of a given conductor depends on the material it is made of, and on its dimensions. For a given material, the resistance is inversely proportional to the cross-sectional area; for example, a thick copper wire has lower resistance than an otherwise-identical thin copper wire. Also, for a given material, the resistance is proportional to the length; for example, a long copper wire has higher resistance than an otherwise-identical short copper wire. The resistance R and conductance G of a conductor of uniform cross section, therefore, can be computed as

where is the length of the conductor, measured in metres , A is the cross-section area of the conductor measured in square metres , σ (sigma) is the electrical conductivity measured in siemens per meter (S·m), and ρ (rho) is the electrical resistivity (also called specific electrical resistance) of the material, measured in ohm-metres (Ω·m). The resistivity and conductivity are proportionality constants, and therefore depend only on the material the wire is made of, not the geometry of the wire. Resistivity and conductivity are reciprocals: . Resistivity is a measure of the material's ability to oppose electric current.

This formula is not exact: It assumes the current density is totally uniform in the conductor, which is not always true in practical situations. However, this formula still provides a good approximation for long thin conductors such as wires.

Another situation for which this formula is not exact is with alternating current (AC), because the skin effect inhibits current flow near the center of the conductor. Then, the geometrical cross-section is different from the effective cross-section in which current is actually flowing, so the resistance is higher than expected. Similarly, if two conductors are near each other carrying AC current, their resistances will increase due to the proximity effect. At commercial power frequency, these effects are significant for large conductors carrying large currents, such as busbars in an electrical substation, or large power cables carrying more than a few hundred amperes.

\

Conductor ampacity

The ampacity of a conductor, that is, the amount of current it can carry, is related to its electrical resistance: a lower-resistance conductor can carry a larger value of current. The resistance, in turn, is determined by the material the conductor is made from (as described above) and the conductor's size. For a given material, conductors with a larger cross-sectional area have less resistance than conductors with a smaller cross-sectional area.

For bare conductors, the ultimate limit is the point at which power lost to resistance causes the conductor to melt. Aside from fuses, most conductors in the real world are operated far below this limit, however. For example, household wiring is usually insulated with PVC insulation that is only rated to operate to about 60 °C, therefore, the current in such wires must be limited so that it never heats the copper conductor above 60 °C, causing a risk of fire. Other, more expensive insulation such as Teflon or fiberglass may allow operation at much higher temperatures.

The American wire gauge article contains a table showing allowable ampacities for a variety of copper wire sizes.

Isotropy

If an electric field is applied to a material, and the resulting induced electric current is in the same direction, the material is said to be an isotropic electrical conductor. If the resulting electric current is in a different direction from the applied electric field, the material is said to be an anisotropic electrical conductor.

Bibliography

Pioneering and historical books

- William Henry Preece. On Electrical Conductors. 1883.

- Oliver Heaviside. Electrical Papers. Macmillan, 1894.

Reference books

- Annual Book of ASTM Standards: Electrical Conductors. American Society for Testing and Materials. (every year)

- IET Wiring Regulations. Institution for Engineering and Technology. wiringregulations.net

References

- Fink and Beaty, Standard Handbook for Electrical Engineers 11th Edition, pages 17–19

is the length of the conductor, measured in

is the length of the conductor, measured in  . Resistivity is a measure of the material's ability to oppose electric current.

. Resistivity is a measure of the material's ability to oppose electric current.