| Revision as of 00:15, 29 June 2014 editFiledelinkerbot (talk | contribs)Bots, Rollbackers275,811 edits Bot: Removing Commons:File:Reconstruction of king Tut.png (en). It was deleted on Commons by Steinsplitter (No license since 2014-06-19. Please read the intro of [[Commons:COM...← Previous edit | Revision as of 06:15, 29 June 2014 edit undoFiledelinkerbot (talk | contribs)Bots, Rollbackers275,811 edits Bot: Removing Commons:File:Fells comparisons of Oconnors text.png (en). It was deleted on Commons by JuTa (No license since 2014-06-19. Please read the intro of [[Commons:COM:L...Next edit → | ||

| Line 138: | Line 138: | ||

| :''And the oldest of the sages is to make known the verdict to the assembled people, declaring that all men should know that they may expect justice in misfortune in these precincts, and that whether it be fraud that is the cause of a dispute, or be it lust, or malice aforethought, or the death of a slain man, or a boundary line that is under survey, crime will be countered by justice, moderated by clemency.'' | :''And the oldest of the sages is to make known the verdict to the assembled people, declaring that all men should know that they may expect justice in misfortune in these precincts, and that whether it be fraud that is the cause of a dispute, or be it lust, or malice aforethought, or the death of a slain man, or a boundary line that is under survey, crime will be countered by justice, moderated by clemency.'' | ||

| ] | |||

| The one thing which unites the chronicle and related scrolls is the peculiar and unique lettering not found in other manuscripts, which leaves no room for doubt as to pedigree. Left is Fell’s illustration of O’Connor’s text (C) which he compares to other ancient alphabets. Anyone with clues as to the whereabouts of this source is requested to get in touch via the external below as it may be another candidate for the carbon-dating agency in Cambridge. | The one thing which unites the chronicle and related scrolls is the peculiar and unique lettering not found in other manuscripts, which leaves no room for doubt as to pedigree. Left is Fell’s illustration of O’Connor’s text (C) which he compares to other ancient alphabets. Anyone with clues as to the whereabouts of this source is requested to get in touch via the external below as it may be another candidate for the carbon-dating agency in Cambridge. | ||

Revision as of 06:15, 29 June 2014

| This article is an orphan, as no other articles link to it. Please introduce links to this page from related articles; try the Find link tool for suggestions. (December 2013) |

The Chronicles of Eri is a collection of purported ancient Irish manuscripts which detail the history of Ireland, translated by Roger O'Connor in 1822.

Content

Volume one

Roger O' Connor published the "Chronicles of Eri" in 1822. He originally proposed it as the 'Chronicles of Ulladh (Ulster)' as it purports to relate to the history of the ruling dynasty of that province. Roger O'Connor claimed direct descent from Ulster's ruling dynasty, recalled as the Er in the chronicles and Ir in Irish manuscripts. The chronicle was thus simply introduced as "by O'Connor" in keeping with an Irish tradition that the head of a clan need not employ his first name.

The Chronicles of Eri were published in two volumes, although the first formally assumes this title, it is referred to locally as the "Chronicles of Gaalag" (Galicia). This is represented by the concluding section of some 91 pages in volume 1. The remainder of this volume is a lengthy thesis containing O'Connor's own opinions and conjectures on history on the chronicle under a heading of "demonstration".

The chronicle of Gaalag breaks down into two significant parts. The first is attributed to Eolus, a king of Galicia who represents the oral traditions of history that he claims prevailed in his time. He claimed to have travelled to Sgadan (Sidon) where he learnt the art of writing from the Feine (Phoenicians). His account contains little detail, though it claims to allude to a series of earlier ages, starting with the original migration of Gaels out of the Indus valley following the "flood of Sgeind" thousands of years before his time. He claimed his forebears were the peoples now alluded to as Gutians and Hurrians; nomadic tribes who menaced the settled peoples of Mesopotamia, which the chronicle infers as enslaved populations. There is no agreement as to how the dates of these events were known to O’Connor in 1822.

The next Age is alleged to have followed Assyrian king Sargon's defeat of the nomadic Gaels, and their migration up the river Euphrates under their own king Noai, also alluded to as Er and Ard-fear. The chronicle contends this king led his people to safety near Mount Ararat where they settled calling the region of ard-mion (Armenia, literally high-mine). The chronicle infers that the predominance of the descendants of Noai (Biblical Noah) was due to their ability to work bronze which gave them superior weapons. The people are said to have flourished and extended their realm on all sides under Iath-foth, or Mac-Er, and his successor Og (Armenian Hayk). This part of the account was deemed disrespectful of the Biblical story of Noah, and was to upset many in O'Connor's time as the Old Testament was then seen as sacrosanct by many. There remains no accepted explanation as to how the dates inferred for Sargon and accorded to Hayk or Og should converge so closely on modern estimates.

Subsequently a descendant king named Glas was given the land of Ib-er (place of the Er, also called Tubhal, an area later known as Caucasian Iberia, not to be confused with Iberia or Spain) by his brother Dorca. Glas appears in Irish manuscripts as 'Goídel Glas', stories surrounding him converge loosely on the chronicle but with alternative overlays. The next chronicled Age was marked by the migration of Calma from Caucasian Kingdom of Iberia, to Galicia in Spanish Iberia in search of his comrades taken into bondage by Phoenicians to work the mines. Among his descendants was Eolus who claimed to be the first of dozens to leave a written record of his own times.

Following the death of Eolus the role of keeping the chronicle was assigned to an appointed secretary of the king known as Ard-ollamh. An embassy was sent by Don, successor to Eolus, to negotiate with the kings ruling over the Phoenicians, listed as Ramah then Amram then a second Ramah. There is no accepted theory as to how O’Connor around two centuries ago could have known the names and dates now ascribed to these Egyptian Pharaohs, or that they were overlords to the Phoenicians (confirmed by the Phoenician Amarna letters found in 1887, which date from around the time Eolus claimed to have learnt to write in Sidon). Amram was chronicled as having succeeded his uncle Ramah in 1350 BCE, the date now assumed by Egyptologists is 1341-32 BCE. Despite his records in the chronicle, Amun-ra is still formally said to have disappeared from history until the discovery of his tomb in 1922. The chronicle is unique in inferring these figures as kindred to the Gaels, it alleges that Ramases I did send Ollamh to abide amongst the Geal in Gael-ag, and the teachers of Aoi-mag did give knowledge unto the nobles. In 2009 the unlikely sounding claim was supported by DNA tests on Amun-ra or Tutakamun (‘’the living image of Amun-ra’’) showing him to carry the Gaelic R1b1a2 haplogroup.

The accounts of the following three centuries were attributed to various ollamh's whose names are recalled in the chronicle. At this period there was little recorded by many as they complained their office was undermined by the powerful priests of Baal, chronicled as crom-fear, who were hostile to the secular writings of Eolus against them.

Volume one is concluded by what it claims were momentous events prompting the exodus to Ireland. Following a row with the Phoenicians, who were generally chronicled as representing Egyptian interests abroad, the Gaels were attacked by Sru or Hercules and the Gaelic king Golam slain in battle. The chronicle claimed an adage by which the Gaels lived was '’die or live free’’ so the remnant who had survived war or enslavement set sail for Ireland in the wake of Ith who had been killed there when scouting the land. Galician traditions concerning Breogán’s tower or the tower of Hercules follow the chronicle more closely than do Irish manuscripts, although only the chronicle claims that both of the tower’s names specifically recall the same story.

Volume two

Volume II claims to represent the history of Gaelic Ireland from its alleged beginning in 1006 B.C. The land was won from the Tuatha de Danaan who had invaded some two centuries earlier, victory going to the relatively small force of Gaels partly as a result of their superior weapons but mainly due to help from the natives (Fir-gneat) who the chronicle claims had been enslaved and abused by the Danaan. A treaty with the Danaan reserved for them the province of Connaught and Clare (west of the Shannon).

Up to this time there is little correspondence between the claims of Irish manuscripts and the chronicle, but from this period forward the chronicle follows much the same names and approximates the reign durations of pagan kings recalled in manuscripts. However manuscripts typically relate one or two lines for each king, whereas the chronicle affords many lengthy accounts. Manuscripts generally allude to Golam as Milesius or Mil Espaine (soldier of Spain). The loose concordance with manuscripts has led to various charges that the chronicle was fabricated off the back of them, however in those respects which the chronicle contradicts the manuscripts, subsequent evidence invariably aligns towards the chronicle. For example the manuscripts commonly speculate upon those lakes that appeared in a certain reign. The chronicle counters that only one lake was flooded in the pagan era around 250 BC:

- as an arrow goeth from the bow, and water rushed in to the hollow of the land, and therein lay, and they are called the waters of Gurna, within Coriat.

Drainage works carried out after 1822 in the middle of the 19th century ‘discovered’ that Lough Gur had indeed flooded and that the flood helped preserve a rich archaeological record of its settlement before this time. Although this may appear persuasive evidence that in usual circumstances might elicit some to reconsider the chronicle, both it and its author had been so roundly calumniated on spurious grounds that there is no evidence of any public notice of this or any other point of hard evidence until this introduction here on wiki in midsummer 2014, (and earlier that year in a little visited related website).

The accounts of the Irish era are generally more substantial than those of the Galician era, but relate only to the period as it was perceived in Ulster where the Ollamhs were reserved priority over the priests or crom-fear, who dominated the southern provinces. Many ollamhs return to a longstanding theme critical of the priests, accusing them of corruption, and advancing their interests by promoting violence and ignorance among the people.

As might be expected at this point the chronicle becomes more insular, though occasional references are made to the outside world. For example in 914 BC Ithbaal, the high-priest (ard-cromfear) of Tyre is said to have succeeded and together with his daughter Ishbaal spread the practice of Baal worship through all Isreal and the collective nations. His embassy in Ireland attempted to reinforce the crom-fear with bribes to king Tigernmas, as the chronicle claims the corruption of these priests was a vehicle by which the Phoenicians extended their bronze mining and trading interests. The chronicled version of the story of Tigernmas and Crom Cruach, although challenging to conventions of the manuscripts, was lent support In 1923 when French archaeologist Pierre Montet, working in Jbeil, (historic Byblos) found the Ahiram sarcophagus, tentatively dated to around this period. Its Phoenician inscription starts: A coffin made (by) Ittobaal, son of Ahirom, king of Byblos. A little earlier in 1921 relics deemed to be Crom Cruach were found in Co.Cavan.

By far the most significant figure claimed of the Irish era was Eocaid Ollamh Fodhla of Ulster's line of Er, a reputed giant of his time (which allegedly concluded in 663 BC). On his appointment his close friend and Ollamh, Neartan said of him "in years a youth, in wisdom, aged is he". The chronicle maintains Ollamh Fodla unified the long feuding island by setting up a three yearly government assembly and games at Tara which were to become a focus of the chronicle from his time forward. He is credited with setting up the office of ‘Ard-righ’ (high king) and instituting Ireland's first formal legal code.

Centuries of relative peace are said to have flowed from Ollamh Fodla's institutions, though the level of inter-provincial feuding grows towards the close of the chronicle in 7 BC. The chronicle concludes abruptly with little hint as to the circumstances surrounding the end of all it claimed to represent. Irish manuscripts and tales from the Ulster cycle suggest that Conchorbar Mac Nessa's war with his cousin Fergus mac Róich was one possible cause. (Fergus was claimed by Roger O'Connor and others to have been his ancestor).

Contentions upon authenticity

The chronicle purports to represent centuries of written history long before the time of St. Patrick when it is widely believed that the formal alphabet first was introduced to Ireland, a primitive form of writing known as ogham is thought to have first emerged around a century earlier. Consequently the chronicle appears most implausible and has been dismissed as a fraud. Against all usual instincts, the belief that the chronicle of Eri must be a fraud has been called into question by a recent study.

The chronicle of Eri has never been the subject of a serious research paper by its critics. A series of often emotive charges has been directed against the chronicle, described by some sceptic’s as reviews. Common among these are fundamental errors which challenge their former characterisation as ‘reviews’ rather than rants as is currently claimed by some.

1) Language of the chronicle

One of the most widely cited reviews was by R. A. Stewart Macalister, although he was not actually reviewing the chronicle, but rather another book premised upon it in the British-Israeli tradition. Macalister is not alone in illustrating all the misrepresentations outlined in this and the next section.

O’Connor’s book title describes his scrolls as being in the ”Phoenician dialect of the Scythian language”. Little of his chronicle may be read without it being apparent that the language he awkwardly alludes to is Gaelic. The chronicle claims that Gaelic was spoken throughout Celtic Europe, this is now recognized by linguists who use Gaelic to interpret Celtic era place-names which are quite homogeneous over a large area of Europe, in line with classical claims of regional dialects of an essentially single Celtic language, now sometimes recalled as common Celtic. The chronicle claims Phoenician traders were not only able to understand this language, but that in fact it was them behind its spread. The old Gaelic for Gaelic is Bearla Feine or the Phoenician tongue.

Macalister takes O’Connor’s Phoenician dialect of the Scythian at face value, complaining of O’Connors ”blank incompetence to deal with the Phoenician histories of Eolus”. He was an authority on Hebrew and accuses O’Connor of making many spelling errors, citing the earlier noted Ard-mion (Armenia). Anyone taking a cursory look at the chronicle would soon see that it is originally in Gaelic from start to finish, and that the words depicted as spelling mistakes are presented as the Gaelic originals, each of which O’Connor carefully rendered in italics to distinguish them from the flow of his English translation.

2) Authorship of the chronicle

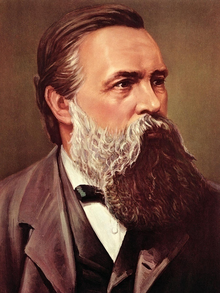

Frederick Engel’s in his History of Ireland of 1870 alleged the original manuscript is a verse chronicle chosen at will. The publisher is Arthur O'Connor. Arthur O’Connor was Roger’s brother. Engel’s muses how closely Roger’s son, the chartist leader Feargus O’Connor, resembles his uncle Arthur’s portrait in the front of the chronicle, (this of course being Roger).

Arthur O’Connor had personally organized the 1796 French invasion of Bantry Bay following his treaty with Lazare Hoche (In spite of common perceptions, Wolfe Tone was unable to attend this critical treaty at Angers, Arthur’s modern biographers’ concur that his real role in shaping Irish history was considerably more significant than the marginal memorials to him might suggest).

Various commentators follow Macalister who infers that the chronicles original author was only or principally Eolus in line with a similar claim made by the Quarterly review in 1832 (Vol 46, this review, like Macalister, was also addressed towards another related publication).

The Quarterly review admits it was written from an Anglo-Saxon perspective, the authors not altogether happy with the O’Connor brothers; leaders of United Irishmen who sought, and who may have succeeded in removing English rule from Ireland if what was called the worst storm in a century had not scattered the large French fleet which had completely alluded British naval defences carrying some 15,000 troops heading for Ireland, the protracted storm then pulled out the fraction of them that made it to Bantry bay back out to the Atlantic. At this time the British army was largely committed to engagements abroad, and the countries defense in the hands of informal militia groups, many hostile to the ruling oligarchy in Dublin Castle. At Bantry Bay circumstantial evidence suggests Roger O'Connor under the guise of leading signalman succeeded in supplying each French ship with a local harbour-pilot and in having this officially recorded as a tactical error.

Napoleon Bonaparte was an ally of the O'Connor brothers, he and his successors to the French executive rejected dissenting opinions in the fractured United Irish executive and accepted Arthur O’Connor’s claim to be its principal director so he was appointed to the position of General over Irish regiments in France. Roger O’Connor was the only member of the United Irish executive who managed to return to Ireland. Roger’s cousin Daunt recalls correspondence of 1811 from a library in Caen in which Napoleon raises his unconditional offer of troops to Ireland from 25 to 60 thousand if consultations with O’Connor suggested that sufficient numbers of the disaffected were still prepared to fight with him in Ireland. Roger O’Connor later claimed he acquired Dangan Castle from Napoleon’s enemy, the Duke of Wellington to receive Napoleon when he arrived. Opposing Wellington at Battle of Waterloo was Marshal Grouchy, later uncle-in-law to Arthur O’Connor.

This background regarding Arthur was largely known at the time of the publication of the chronicle in 1822, Roger was widely suspected but the smallest extent of his activities was not proven. Circumstantial evidence suggests his undercover contributions to the Nationalist cause first as Captain Right and then ‘’Captain Rock’’ (Roger O’Connor, King) continues to elude history in large part due to a long series of calumniation’s directed against him, initially by his enemies in Dublin Castle and the house of Commons, and subsequently also the Catholic mainstream, in large part due to the deep offense admitted by ] (and his main source upon Roger, Father Crolly) to the highly secular views of both Roger and Arthur. Madden’s introduction illustrates the colours he uses to paint his portrait of Roger O’Connor: he might have served as a model mind for the Frankenstein creation of Mrs. Shelley's powerful imagination’... ‘he spent a large portion of that life forging lies, concocting deliberate schemes of imposture, and promulgating literary forgeries with a view of hurting the principles of Christianity. Research for Roger’s first biography In orbit of a local star(due for publication), suggests that each of the main allegations against his name is unsupportable by the lowest standards of today.

The O’Connor brothers had been schooled by Major Morris (who served in the British army in the American war of independence, but who worked under the cover of a feigned name for Washington). Both brothers had been to Trinity College, Dublin to study law. Lawyers from Trinity were to form a nucleus of the United Irish leadership. Enlightenment ideas and the American and French revolutions were foremost influences for the brother’s long fight for democracy in Ireland.

This background may help explain why the Quarterly review, along with other some early British reviewers were not naturally well disposed to O’Connor’s chronicle, primarily objecting to it on religious or Christian grounds in spite of the obvious issue that the chronicle concludes before the Christian era commences.

As noted above, the Galician king Eolus was the chronicle’s creator and first contributor, but not its sole or principle author; he was followed by many others, all of whom inferred their records were contemporary with the kings reigning during their employment as ard-ollamh. The writings attributed to Eolus comprise around 25 of the first 37 pages of the chronicle proper (O’Connor’s footnotes account for the difference). Before editing this page it read The contents (a lengthy 900 pages) are alleged to have been written by a Scythian chief called Eolus.

3) Content of the chronicle

The last quotation introduces a third common error recycled by critics. Much of the 900 pages alluded to above are O’Connor’s own demonstration; nowhere does he suggest this to be anything but his personal thesis. It is clearly separated away from the chronicle so it is not known why so many ‘reviewers’ should confuse O’Connor’s conjectures with the chronicle. The content of the chronicle does not feature prominently in commonly cited reviews of it, rather these tend to question O’Connor’s insights or conjectures which are inferred to represent part of the chronicle proper.

In defense of the critics alluded to above, none claim to have personally studied the chronicle, the fact that they were often reviewing related works and their tendency to recycle earlier misrepresentations of the chronicle suggests that some may have had little more knowledge of the chronicle than an earlier ‘review’. A claim is made in the academic press that the chronicle has been disproven, but an email request for detail has proved unsuccessful, and this information eludes the cited source.

Former support for the chronicle

Although now largely disregarded, there has been another series of reviewers defending the authenticity of the chronicle. They tend avoid the errors of its critics and show evidence of being acquainted with the work.

In July 1822, The Monthly magazine, introduced Mr. O’Connor’s work as “The most original and extraordinary which the printing press ever brought before the world”. They had little doubt about its integrity since included was a facsimile of one of the source scrolls The roll of the laws of Eri copied from the original MS.

James Roche, a prominent banker was described by Madden as an eminent literary man and historical antiquarian), he concludes that circumstantial evidence surrounding O’Connor’s claims dictates no foundation whatever for the charge made against him of attempting a literary fraud.

Scottish clergyman Peter H Waddell in 1875 published his work arguing for the authenticity of the Ossianic poems. He considered the Chronicles of Eri, forgotten or treated with, contempt as an imposture, but now capable of verification in all substantial respects. Waddell was unusual in demonstrating that the chronicle need not be seen as a threat to a minister of the gospel as he alludes to himself.

In the 1830’s a German version of the chronicle and was attended by a small flurry of publications premised on its authenticity. A century later another cluster of approving articles appeared in the German press in the wake of a book by L. Albert or Hermann which argued passionately for the case as is suggested by his book titles: Six Thousand Years of Gaelic Grandeur-unearthed. The most ancient and truthful chronicles of the Gael ... The Chronicles of Eri and later The Buried Alive Chronicles of Ireland; an open challenge to the Celtic scholars of Breo-tan and Eri. He concluded the war against the revelations of Eolus is not only a crime against truth, scientific honesty and the moral advancement of humanity, it must also be denounced as one of the most meaningless acts in the long history of human aberrations!. It seems possible his second work was never read by any of the scholars he was addressing as it currently is down to around 4 library copies worldwide.

The question of the chronicle’s placement here on wiki as a literary hoax is of some significance as the chronicle claims to double the course of Gaelic history. The question as to whether the chronicle is a fraud or not is a simple black and white, yes or no issue, at the heart of which lies the question of source scrolls.

Source scrolls

A universal charge made by critics against the chronicle is the alleged non-existence of source scrolls. This has not been conducive to promoting interest in the chronicle so here is introduced evidence for O’Connor’s source scrolls which comprise six separate leads.

1) The O’Connor scroll

Roger O’Connor advertised his intention to leave a book of law by Eocaid Ollamh Fodhla to the nation. The chronicle claims he ruled from 703 BC to 663 BC. Ollam Fodhla occupies disproportionate space in the chronicle as his alleged legacy in terms of his personal effect on subsequent history, politics and the rule of law far eclipse that of other chronicled kings in Ireland.

Illustrated left is the one surviving scroll left by Roger O’Connor in the public domain. It is listed at the John Rylands library in Manchester as Irish MSS 118 and also has been called the O’Connor scroll. In view of its potential to transform over a millennia of prehistory into history, the general disinterest in it appears extraordinary. There does seem to be evidence that anyone has even take the time to read what it says, although to decipher the Gaelic, which follows the form illustrated in the chronicle of Eri, should doubtless require text enhancement equipment as the writing is too faded to be legible to the naked eye.

Following a brief examination of the scroll in January 2012 a formal proposal was presented to the library offering to pay for the carbon-dating of the scroll, with assurances from a laboratory in Cambridge that the procedure would have negligible impact as only the smallest sliver from the edges of one of the skins would be needed.

At the time of writing (June 2014) no response to this proposal has been forthcoming. The scroll is classed by the library as a 19th Century document as it is considered a forge or palimpsest, this being a reason offered for the delay in making a decision. The plausibility of a theory that proposes O’Connor should have anticipated carbon dating in 1822 and prepared evidence to circumvent it is perhaps best judged by the reader.

In an effort to press the case, an email campaign was launched alerting academics in history and archaeology departments across the British Isles to this and other persuasive evidence showing that the chronicle deserves to be revisited; however only a handful of the hundreds approached expressed interest in looking at this question, but most were prematurely put off by claims that the chronicle had been researched and disproven, formally here on wiki and in much other documentation attacking the chronicle of Eri.

Grounds for believing that the library is incorrect in its assessment of its scroll 118 as a palimpsest are introduced in the external website eolus.esy.es which is alone in introducing all known research into the chronicle. If there is a reader who agrees that something which has the potential to be the most important lead in the history of history should be salvaged from its state of academic scrap, they are urged to support the campaign to get it read, carbon-dated and to persuade an academic to consider the evidence regarding it. (The scroll is physically being well cared for and the library staff can be commended for the quality of their measures to help preserve it).

This scroll, if it is the work of Eochaid Ollamh Fodhla (or a copy of it made before O’Connor’s time), together with all the chronicle of Eri claims to represent, is referred to as the Psalter of Tara in Irish manuscripts, being long lamented as lost.

2) The ‘O'Connor manuscript’

Barry Fell was a professor of zoology at the Harvard University who risked his reputation with a series of books outlining his research into New World epigraphy (Native American inscriptions). Fell's work, represented by a mix of Phoenician and Celtic trails was not well received in academia; much of it was dismissed as pseudo-archaeology.

In his book ‘Saga America’, Fell introduces a legal tract or O'Connor manuscript, yet he clearly had no inkling about Roger O’Connor or his chronicle as he believed it to be Iberian in origin. If the chronicle is ever accepted as authentic it may help rescue Fell’s bruised reputation and transform him into one of the greatest modern investigators of history, since it is unique in affirming the context of Fell’s main conclusions.

Fell introduces his sample:

- A few years ago, a colleague in Britain, W. Edmund Filmer of Surrey, came across a peculiar document — or, more correctly, an eighteenth-century engraving reproducing the document, that had once formed part of a collection of early Irish manuscripts...

- The O'Connor manuscript presents a new aspect of the ancient Irish scene, for it proves to be a fragment of an account written by a Spanish Celt — more precisely a Spanish Gael (for such is his language) — dealing with aspects of Irish law such as would be of interest to other Spanish Gaels who might intend to visit the country.

- Certain references in the document to wheel-money and to Etruscan coins and Tyrrhenian "Bulls" (i.e., coins of Italy and Sicily on which bulls are depicted) show that the document is itself a second-century copy of a much older document that must have been written in the third century B.C., when such coins were in circulation. Filmer suggests Galicia as the source of the original manuscript.

The full text of Fell’s translation may be seen in his book or in the supporting website. If genuine, this pagan law is in some respects more humane than our own as it concludes with how to cleanse the stigma of the plaintiff and realise a full return to innocence:

- if on weighing the case, one and all having heard the complaint, they declare a verdict of not-proven, then let the picket be hewn down as needless, for there is no guilt of manslaughter on his part. Thereupon straightway the assembly shall march rejoicing to any of the well-known sacred springs, and to the oracle there let a donative be given larger than is customary, for the sake of the acquittal. And thereupon they are to immerse their man in the depths of the spring.

- And the oldest of the sages is to make known the verdict to the assembled people, declaring that all men should know that they may expect justice in misfortune in these precincts, and that whether it be fraud that is the cause of a dispute, or be it lust, or malice aforethought, or the death of a slain man, or a boundary line that is under survey, crime will be countered by justice, moderated by clemency.

The one thing which unites the chronicle and related scrolls is the peculiar and unique lettering not found in other manuscripts, which leaves no room for doubt as to pedigree. Left is Fell’s illustration of O’Connor’s text (C) which he compares to other ancient alphabets. Anyone with clues as to the whereabouts of this source is requested to get in touch via the external website below as it may be another candidate for the carbon-dating agency in Cambridge.

3) Tract of the laws of Eiri

The third sample was reproduced at the launch of the Chronicle of Eri in 1822. A pull out facsimile is evident on original editions of the book, though most of it is missing from online digitized versions. The above noted website contains an untranslated interpretation of the Gaelic, together with the original text of a simple legal constitution. Shown here is only its title.

This source may be older than that illustrated by Fell which includes the letter p. The letter p does not appear to be used at all here, the word bobail apparently alluding to people (inferring the word to be from cattle of Baal), though the old Irish form usually takes a p (called in Gaelic soft (or aspirated) b). In Gaelic text b is unique in its stem protruding above the body of the letter where the aspiration dot should go so placing it underneath as p appears a logical evolution.

4) Exhibited manuscripts

Godfrey Higgins in his 1827 book remained sceptical of O’Connor, though he concedes that "O'Connor published a work, in two large volumes, from Irish manuscripts, which were deposited for public inspection, for some time, in London". He complains O’Connor did not furnish an adequate "critical dissertation on the genuineness and antiquity of the MSS", as though doing so might present a hoaxer with more problem than a public presentation of the original’s. Two years we find critics complaining "till the manuscripts .. of O’Connor’s chronicles of Erin, shall be pointed out and exhibited" they should be seen as fable. This appeared in an American journal Southern Review, in a review of Higgin’s work in 1829 that appears to have overlooked the above notice. The sceptical position of Higgins against the chronicle appears bizarre, being contrary to his thesis, which is closely aligned to it, as is evident from his title: "The Celtic druids or, an attempt to show that the druids were the priests of Oriental colonies who emigrated from India".

These exhibited scrolls may be the same as source 3 above as that facsimile was testified as an authentic copy by Sir R Phillips and Neale & son in London, though it is short and the description by Higgins hints at more substantial source scrolls of the chronicle itself (3 is not translated in the chronicle, probably being one of the Tanisteact legal documents occasionally referenced). (One online edition of the above noted facsimile differs a little claiming it to have been Copied from the original MS by J Craig. Lithey? Islington).

O’Connor speaking of his scrolls argues:

- "Should any captious person be inclined to entertain suspicion of the antiquity of these manuscripts, I beg leave to observe, that I do not presume to affirm that the very skins, whether of sheep or of goats, are of a date so old as the events recorded; but this I will assert, that they must be faithful transcripts from the most ancient records; it not being within the range of possibility, either from their style, language, or contents, that they could have been forged".

He gives little hint as to their original location, a tomb or vault is hinted at by his "reclaiming from the bowels of the earth the most ancient manuscripts" and elsewhere:

- "permit me to make you acquainted with another man of ancient days, who lived about 50 years later than Moses, and hath also compiled the traditions of his nation, from the earliest point of time noted, whose writing bed-fellow with the mouldering bones of the illustrious dead for ages, hath been rescued from the tomb by me, his son. This man was Eolus".

5) Claimed as confiscated

Crown forces had allegedly seized some of O’Connor’s scrolls from his cell around in 1799, having detained him in prison without charge, following his many ‘acquittals’ from a series of legal failures by Dublin Castle to frame him, all documented by himself and Francis Plowden (who was subsequently exiled for criticizing Dublin Castle).

- "I employed my time in writing a history of that ill-fated land, which I had brought down to a very late period, when an armed force of Buckinghamshire militia men entered my prison, and all the result of my labours, with such ancient manuscripts as I had then by me, were outrageously taken away, and have never since been recovered".

O’Connor is widely accused of being secretive about his sources; he had little reason to trust a deeply sectarian government that made no pretence of their hostility to him or his Republican cause. O’Connor lived under the gloomy twilight of the penal era, he praised Henry Flood for trying to preserve unrelated Irish manuscripts and complains at Dublin Castle’s measures to oppose him which he infers led to their loss.

In view of the determined and often difficult steps of Dublin, London and Belfast to reconcile a turbulent past towards a peaceful future, it may be in the interests of all sides to cooperate in any remaining clues relating to this claim.

6) Authentic history of Ireland

The most substantial lead that may lead an investigator to potentially surviving source scrolls stems from the work of Rev. JJ O’Carroll’s parallel "Authentic history of Ireland from the earliest times down" which may be seen online.

O’Carroll follows O’Connor in not disclosing his source which was to see his own Herculean effort buried no less quickly, though the explanation in view of his time, Clerical position, and secure location in Chicago, seem to defy simple speculation. The only thing that is clear is that O’Carroll’s source consisted of two rolls since he follows them in through his two book parts, breaking with the "end of the first roll" in reign of Roitheasac in 558 B.C. Most early Irish MSS are not in roll format.

O’Carroll’s original source for his history may have followed from his position as chief librarian of the Gaelic league of America, though a more likely explanation flows from his family connections. His father was parish priest in Castle Connor, so named from the last of the Sligo O’Connor’s. The Annals of Lough Key claim them to have descended from the last Irish high king Roderick or Rury O’Connor, yet their family crest incorporated the golden lion of the Kerry O’Connor in line with Roger O’Connor’s claim of his line (descendants of the line of Er or Ir) providing the last reigning high king. Le Fanu documented the extraordinary circumstances surrounding the killing of the last of this line via an account of the parish priest of Castle Connor. His Gothic-horror story is made more surreal by further research into O’Connor’s killer ‘Fighting Fitzgerald’.

Breandan MacConamhra (a former director of Sligo Institute of Technology) advised that O’Carroll’s Gaelic appeared to be a form of bearla na scol (speech of the schools). The chronicled word for school was mur n’ollamh (wall of the ollamh or teacher). He considered that O’Carroll’s version must have followed some awareness of O’Connor’s so the related website shows grounds for believing that O’Carroll’s version was completely independent. For example, O’Carroll makes errors upon O’Connor’s volume one (The chronicle of Gaalag is absent from his own, though he could not have missed it if following O’Connor), he presents evidence useful for scientific authentication absent from O’Connor’s version of the Irish chronicle and he gives the full Gaelic text (which furnishes much of its own evidence, for example the whole sample of some 127,000 words are compounds of a small core of under 2000 keywords, consistent with a language in its primitive form, though each common word retains a multiplicity of spellings).

Tests of authenticity

The chronicle maintains that the ollamh’s were under oath to record only the truth. At times it is claimed this led to friction between ollamhs and the kings they served. At other times the needs of propaganda were evidently opposed to the service of truth, for example the chronicle contains the odd example of exaggerated enemy losses with implausible numbers quoted, however in such instances the crafty ollamhs appear careful to exonerate themselves from charges of falsehood simply by claiming to truthfully report the kings (improbable) words on the subject.

Thus, on its own terms, the chronicle may be regarded as an all or nothing affair. Either it is an authentic record which effectively doubles the span Irish history with modern standards of integrity, or it is a hoax.

The chronicle contains thousands of individual details; any one that can be shown to be at odds with what has been securely established for the era concerned since 1822, across the spectrum of modern sciences, would offer critics of the chronicle firm ground for their reservations. This was publicly tested on the historical forum historum in early 2014. Although hostility to the chronicle’s claims was considerable, no sustainable point of contention was represented on another dedicated thread despite warnings to skeptics that this may be used as evidence against their position. (The thread concerned is in the controversial history chamber so only accessible to members of the free to join forum).

A factor in the general resistance to consider evidence with respect to the chronicle was the reports formally here on wiki and elsewhere claiming it to have been disproven. Wiki claims to follow the Darwinian principle of evolution, allowing all equal access to edit content with a view to enable an erosion of inaccuracies out of its pages. Skeptics of the chronicle are invited to add considered content to the section that follows.

Current challenges to the chronicle

The initial presumption in the research introduced here was that the chronicle must be a literary fraud. Various pages written to that end have had to be moved across to the other side of the case upon further research. A handful of pages remain in three draft volumes outlining the case for and against, but none can be considered conclusive as in each case there appears evidence on both sides of the question. For example the chronicle claims an assembly hall at Tara, its dimensions given by O’Carroll, which finds little support in the ground. However further research showed the site to have been contaminated by early British-Isreali tradition searches for Biblical figures. Furthermore a medieval Viking document called the king’s mirror claims that every trace of the palace of Tara was carefully removed by the Irish.

The chronicle challenges various conventional assumptions such as the Celtic pantheon largely elicited from Roman era inscriptions outside Ireland, but within Ireland related Archaeology conspires only to the sun, moon and stars of the chronicle, apparently in rejection of all manifestations of received convention. There is now a large corpus of testable details for the chronicled era. For example it is now known that donkeys, mistletoe and round towers were relatively late introductions to Ireland; in 1822 they were thought central to pagan Celtic life, yet checks of the chronicle thus far has alluded any such obvious mistake.

As noted above, skeptics of the chronicle are asked to contribute content here. For those uncertain but wishing a little further information, please get in touch via the supporting site.

Proof of authenticity

The chronicle is concerned with what is called pre-history so called due to the belief that there is no record of the period with respect to Ireland or Britain. Thus there can be no historical challenge raised against the chronicle and it can only be tested against specific details for the period established to a high degree of confidence by means of recent advances in analytic science.

Modern sciences lend considerable support the chronicle. There are hundreds of unlikely appearing claims contained in the 1822 publication which were wholly unproven at that date, but which have subsequently been proven conclusively. These are currently contained across three draft volumes (initially which may be made freely available to readers willing to consider or challenge the evidence presented).

A website dedicated to introducing this research presents an overview or sample of this evidence. This wiki page is not compatible with a presentation of much of this evidence due to the quantity of material concerned and restrictions on the use of supporting illustrations.

Any one point of proof taken in isolation might well be dismissed as a peculiar coincidence. If the diverse evidence is taken together however, no other explanation appears viable than that the chronicle of Eri is indeed as Rev. J.J O’Carroll reintroduced it in 1903: An authentic history of Ireland from the earliest times down. The potential significance of his claim cannot be overstated.

Genetic evidence

Occasionally in the course of researching the chronicle, evidence emerges which is especially persuasive as it shows science relentlessly conspiring to decisively support the chronicle with regard to claims that run completely contrary to the accepted theories on the question concerned. This page outlines a small fraction of lengthy material introduced in the introductory website.

This is a map of the Danaan or Angle M253 halpogroup distribution, which finds its greatest concentration in and around Denmark, (redrawn from another here). Anyone with the least knowledge of Irish history should consider it must be wrong. Connaught was the only province in Ireland to have no record of intensive Norse settlement. No Irish manuscript recalls Connaught as ever being the province of a Teutonic people. In the Viking era, Connaught was unique in having no Viking settlements which were numerous in all other provinces and which became the roots of most Irish cities. In the Norman era, Connaught was the only province to remain wholly Gaelic. In the Cromwellian era, major inflows of British immigrants seized land from the provinces east of the Shannon and famously directed the dispossessed Gaels ‘to hell or Connaught’.

How can this rude evidence be squared with every ounce of history arguing against it? The chronicle is unique in recording Connaught as an exclusive province of the Danaan throughout the Gaelic era. No other manuscript or Annal makes this claim. Furthermore the chronicle is unique in recording enough of the fair headed Danaan’s background, language and names to leave no room for doubt that they were Danes or Angles who spoke a language allied to English. Their word for stone was stan, and they rudely referred to the natives as clots or clodden. The chronicle is wholly unique in claiming Angles predate the Gaels in Ireland. Many should deride at the idea, but seemingly not genetic science. Note that the map follows precisely the chronicled province of Ol-dan-macht which was bounded by the river Shannon, taking in the county of Clare which was subsequently taken by Munster.

Archaeology joins the conspiracy against the common sense with a comprehensive record of distinctive Danaan or Angle hardware. For example the bronzework found in Ireland in the Dannan dominated era (Middle Bronze Age) throughout Ireland is angled or twisted, it stops abruptly when the Gaels are chronicled as arriving, except in Connaught where it features prominently throughout the Gaelic era. Elsewhere Vikings and Angles continued to angle their metal until their retirement from paganism in the early medieval era. The Danaan were chronicled as venerating the sea and again their distinctive forts now called ‘western promontory forts’ testify to this. The chronicle often alludes to the aversion of the Gael to employ stone as a building material, the Danaan in contrast were partial to it as is shown by its prevalence in the forts of Connaught and Clare in contrast to the Gaelic provinces.

Until recently conventional wisdom concurred in believing Le Tene, Halsttatt or Alpine area was the original source region for the Celts. This was upset by genetic evidence showing a strong correlation of the DNA of surviving Celtic peoples with every location chronicled in or before 1822. Frank Delaney presented an influential series on the Celts on the BBC. His website departs from the former consensus and follows the chronicled trail out of the Indus valley noted above: The Celts' ancestors had come from the foothills of the Himalayas, through the Middle East into Europe. The Gaels are chronicled to have come to Galicia in NW Iberia in 1488 BC, from Caucasian Iberia, precisely located by the R1b concentration there in the map to the left. (The names of both Iberia’s and Hibernia seemingly flowing from the place (ib) of the children of Er (Noai)). The chronicle infers numbers in Galicia were diluted following the exodus to Ireland. A further dilution is reported there in the Roman era when much of the population is said to have sacrificed themselves to the chronicled mantra of ‘die or live free’.

The chronicle claims in 1240 BC, Eocaid led his followers through Buas-ce (Basque chronicled as Gaelic ‘Springs-country’,) to Eocaid-tain (Aquitaine or ‘region of Eocaid’ in SE Gaul, where it they apparently still predominate. O’Connor argues that Aquitaine is so named in memory of this chronicled Eocaid.

The remaining Genetic concentrations in West Britain are chronicled as those of the Gael Sciot Iber sent there to mine tin for the Phoenicians. (The Brittany genetic concentration of course represents those who later fled from the Saxons in Britain).

The genetic evidence does not end here. Further evidence courtesy of the Numidian gene pool, the Phoenician gene pool, and peculiarities in the gene pool of Ib Lugad (a Gaelic enclave in Kerry in otherwise Danaan Ireland), may be forwarded to those who request more information via the related website.

Archaeological evidence

The major ally of the chronicle is archaeology as it furnishes 1000’s of testimonies to the chronicle, in some cases at odds with received wisdom's. This is the main subject of volumes A1-3, (introduced in the earlier noted website },though it is likely these will remain in draft form, with limited availability on request, until a qualified academic may be persuaded to consider them).

In departing from received wisdom's, the chronicle answers some of the major questions troubling archaeologists today. For example evidence outside Ireland suggests that the standard dwelling type in the period concerned was the thatched roundhouse, but the ground refuses to reveal these in Ireland and the former northern province of Brigantia in Britain. This and the paucity of burials prompted Barry Rafferty famously to label the people of this period the invisible people. The chronicle answers that this is because tents, not roundhouses were the norm and is quite specific in describing this as a point of difference between the British Briganties and their enemies to their south (that province lay north of the Dee and Humber estuaries). The evidence from the ground concurs precisely with these delineations of the chronicle, but still baffles archaeologists unfamiliar with passages such as this: Do not build permanent houses as they do in Aoi-mag (Phoenician Hemath)for fear you breed covetousness in the neighboring nations, and they come and take your possessions. Dwell in your tents Oh children of Iber! The chronicle was published before the beginning of formal archaeology. It anticipated that most significant Iron age sites should be sufficiently elevated to get a good view of the all important sunrise over the treeline, these are now described as hill forts. The word for entrance, soir-dorus translates as east-door, and again these have been confirmed on most sites.

Another leading question troubling archaeologists is why there is so little evidence of human remains from this period in Ireland. The chronicle answers because the normal mode of interment was a memorial cairn, principally made of trees, constructed over the place of death. It may be that these subsequently collapsed leaving the distinctive barrows that characterize the era, and explains the lack of human remains as burials were regarded as a means of forgetting those who made themselves unpopular. The chronicle claims criminals were punished by bog burials, in rituals designed to erase all memory of those concerned, ironically it is these which survive and support those who seek to characterise this society as a purely barbaric.

Other enigmas concerning the absence of pottery from Irish sites (despite its prevalence in earlier era’s) supports the chronicle which contains no word for pottery or clayware, and infers that the old tradition was that all means to life must be of life. Recent research has discovered numerous fultach fiadh, wholly unknown in 1822. These are the remains of pits of water in remote locations used for cooking deer by means of heating stones. Their concentration in Munster follows the chronicled claim that this was the region most noted for the practice. The chronicled word for deer is fiadh. The following extract relating to the activities of intelligence agents working for Ollam Fodla, who discover a plot to overthrow him during a hunt in Munster (Mumain):

- Ogard in the hunt on a certain day when he called the Gaal together, and as they waited apart for the heating of the stones, they began joking and Breas said: By my word, many moons will not change until the stags and roes of Mumain will have rest...

This heating of the stones would make little sense to someone of the early nineteenth Century, since if contriving a story, should be more inclined to assume that the deer was roasted on a skewer. In addition the chronicle provides an explanation as to why deer bones do not usually accompany such sites- what bones were not taken away as drinking horns or trophies would have been dispersed among our commonly chronicled four legged friends accompanying the hunt!

Evidence of weapons lends particular support for the chronicle which claims that these should be mostly found in and around the Shannon and other boundary rivers, this prediction has proved true.

The chronicle claims of a conservative culture is at odds with the usual depiction of a wide range of disparate feuding fiefdoms at this time. There are dozens of swords, spears and every other class of artifact consistent with a homogeneous conservative culture. Some puzzles may be resolved by the chronicle. For example the bronze on a Lough Gur shield is deemed much too thin for combat, another find at Emain Macha is proposed by the perplexed to be a gong; the chronicle claims the nobility carried these as instruments of status and the clashing of shields is recorded as a usual mode of celebration at assemblies.

The Bandon river described by the chronicle as the frontier between Danaan Ireland and Ib Lugad, a Gaelic copper mining enclave in the South west bounded by the Bandon, established centuries before the main Gaelic invasion. No other Irish MSS offers the slightest hint to this former enclave. Billy O’Brian ‘discovered’ the Bronze Age mines 170 years after the chronicle described them and outlined their background.

Innishannon on the Bandon estuary recently baffled archaeologists as here was found evidence of a large Celtic ‘ring-fort’ some 400 years before ‘Celts’ left any other evidence in Ireland. It has around 2 kilometres of defensive enclosures attending it and lies precisely on the chronicled spot overlooking the mouth of the Bandon from Ib Lugad’s side of the river. (A local newspaper headline formally describing it along the lines of ‘a huge Celtic fort built 400 years before the Celtic era’ appears to have disappeared from the net. Now you should find it just dated to 1200 BC with little note as to why this date remains so odd for such a fort, this is exactly the time the chronicle claims the Danaan first conquered the rest of Ireland).

Sites attesting the claims of the chronicle are numerous. Further information in draft form is available to those requesting it. One example flows from the detailed chronicled burial arrangements at Ard-Braccan barrow which have the unique potential to anticipate the results of a future geo-phys survey. Sceptics of the chronicle are invited to explain how O’Connor could have also predicted the size and location of Dun Ailine before it was discovered, or Lismullen near Tara, re-found by the NRA before burying it under the M3.

A Barbary monkey skull found at Emain Macha appears wholly consistent with the chronicle’s unique claim that Phoenician’s helped build it, while being no less at odds with the subtext of every other account of history.

References

Most of the references below are viewable online. A quick way to find most of the citations here is to google double quotes around a short sample of the quotation concerned.

- "Chronicles of Eri" vol 1 & 2 Roger O' Connor, Published by Sir Richard Philips and Co. 1822

- Monthly magazine or British Register vol 49 1820

- http://www.biography.com/people/king-tut-9512446#awesm=~oHCDdXwIQeZRYS

- Irish Historical Studies, Vol. 2, No. 7, Mar., 1941, pp. 335-337

- According to Jane Hayter Hames in her biography of Arthur O’Connor

- Clifford D. Connor ‘Arthur O’Connor: The most important Irish Revolutionary you may never have heard of’

- A life spent for Ireland W J O’Neill Daunt 1896 Later republished by Irish university press

- United Irishmen their lives and times, Richard R. Madden, Publisher J. Madden & Co. 1843

- Jane Hayter Hames Arthur O'Connor, United Irishman, Collins press 2001

- David P. Henige ‘Historical Evidence and Argument’ University of Wisconsin Press, 2005

- Joep Leerssen, ‘Remembrance and Imagination: Patterns in the Historical and Literary Representation of Ireland in the Nineteenth Century’ Cork University Press 1996

- Peter H. Waddell ‘Ossian and the Clyde’ J. Maclehose, 1875

- Die Schriften des Eolus und die Jahrbücher von Gaelag aus den Chronicles of Eri von O'Connor’. Wilhelm Gottlieb Levin von Donop 1838

- ‘Deutsche Urzeit’, and ‘Alteste und alte Zeit’ (1838)

- ‘Skytho-Gaalen in Orchomenos und Kyrene, Britannien und Irland’,(1834)

- ‘The magusanische Europe’, or ‘Phoenicians in the interior lands of Western Europe to the Weser and Werra’, (1830).

- Barry Fell ‘Saga America’ Three Rivers Press 1983

- Godfrey Higgins The Celtic Druids 1827 republished in 2007 by Cosimo

- Southern Review, Volume 4 1829

- Rev. John J O’Carroll ‘Authentic history of Ireland from the earliest times down’ J.J. Collins' Sons, Chicago 1903

- John Sheridan Le Fanu ‘The Purcell papers’ Dublin University Magazine 1880

- ‘Dear Earthling' Guy L’Estrange Lulu publishing 2014

- See for example ‘The chronicle of Eri’ Oilliol Bearn-gneat from 594 BC

- See the reign of Fionn from 506 BCE

- From the reign of Fionn from 663 BCE

- O'Connor refers exclusively to horns, O'Carroll mentions cups, but his Gaelic might equally be read as wooden or horn methers

- For example O’Carroll’s account of a Munster/Leinster army drowned in the Shannon by the Danaan/Ulster alliance in the time of Seadna from 486 BC

- Vol2 p.88 tells some of the story

- This word is used loosely here in its non technical sense

External links

- Website commonly alluded to above which expands upon related research.

- Full text of O'Connors Vol 1. (This differs from copies alluded to above in having O'Connor's thesis after the chronicle of Gaalag).

- Fulltext of Vol 2 at the Internet Archive

- Full text of 'An authentic history of Ireland from the earliest times down' by J.J. O'Carroll (1901)