| Revision as of 17:06, 2 July 2006 editЪыь (talk | contribs)612 editsm →Trans-Siberian Railway: Krasnoyarsk bridge← Previous edit | Revision as of 10:04, 3 July 2006 edit undoЪыь (talk | contribs)612 edits →Trans-Siberian Railway: ISBNNext edit → | ||

| Line 97: | Line 97: | ||

| : ''For more information, see the article on the ]'' | : ''For more information, see the article on the ]'' | ||

| <ref name="problemregions">Based on a chapter of: Problem Regions of Resourse Type: Economical Integration of European North-East, Ural and Siberia. / Managing editors: V. V. Alexeev, M. K. Bandman, V. V. Kuleshov — Novosibirsk, , 2002.</ref> | <ref name="problemregions">Based on a chapter of: Problem Regions of Resourse Type: Economical Integration of European North-East, Ural and Siberia. / Managing editors: V. V. Alexeev, M. K. Bandman, V. V. Kuleshov — Novosibirsk, , 2002. ISBN 5-89665-060-4</ref> | ||

| The first projects of railroads in Siberia emerged since the creation of the railroad ]-]. One of the first was ]-] project, intended to connect the former to ] and, consequently, to the ]. | The first projects of railroads in Siberia emerged since the creation of the railroad ]-]. One of the first was ]-] project, intended to connect the former to ] and, consequently, to the ]. | ||

Revision as of 10:04, 3 July 2006

The history of Siberia includes a strong civilization of Huns in the 3rd century BC, much more developed than the successors. Another major piece is the history of the settlement of Russians since the 16th-17th centuries, contemporaneous and in many regards analogous to the settlement of Europeans in the Americas.

Pre-history

The shores of all the Siberian lakes which filled the depressions during the Lacustrine period abound in remains dating from the Neolithic age; and numberless kurgans (tumuli), furnaces and so on bear witness to a much denser population than the present. During the great migrations in Asia from east to west many populations were probably driven to the northern borders of the great plateau and thence compelled to descend into Siberia; succeeding waves of immigration forced them still farther towards the barren grounds of the north, where they melted away.

According to Radlov, the earliest inhabitants of Siberia were the Yeniseians, who spoke a language different from the Ural-Altaic; some few traces of them (Yenets or Yeniseians, Sayan-Ostiaks, and Kottes) exist among the Sayan Mountains.

The Yeniseians were followed by the Ugro-Samoyedes, who also came originally from the high plateau and were compelled, probably during the great migration of the Huns in the 3rd century BC, to cross the Altay and Sayan ranges and to enter Siberia. To them must be assigned the very numerous remains dating from the Bronze Age which are scattered all over southern Siberia. Iron was unknown to them; but they excelled in bronze, silver and gold work. Their bronze ornaments and implements, often polished, evince considerable artistic taste; and their irrigated fields covered wide areas in the fertile tracts. On the whole, their civilisation stood much higher than that of their more recent successors.

Eight centuries later Turkic peoples such as Khakases and Uyghurs, also compelled to migrate north-westwards from their former seats, subdued the Ugro-Samoyedes. These new invaders likewise left numerous traces of their stay, and two different periods may be easily distinguished in their remains. They were acquainted with iron, and learned from their subjects the art of bronze-casting, which they used for decorative purposes only, and to which they gave a still higher artistic stamp. Their pottery is much more perfect and more artistic than that of the Bronze period, and their ornaments are accounted among the finest of the collections at the Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg.

This Turkic empire of the Khagases must have lasted until the 13th century, when the Mongols, under Jenghiz Khan, subdued them and destroyed their civilisation. A decided decline is shown by the graves which have been discovered, until the country reached the low level at which it was found by the Russians on their arrival towards the close of the 16th century.

Khanate

In the beginning of the 16th century Tatar fugitives from Turkestan subdued the loosely associated tribes inhabiting the lowlands to the east of the Urals. Agriculturists, tanners, merchants and mullahs (priests) were called from Turkestan, and small principalities sprang up on the Irtysh and the Ob. These were united by Khan Ediger, and conflicts with the Russians who were then colonising the Urals brought him into collision with Moscow; his envoys came to Moscow in 1555 and consented to a yearly tribute of a thousand sables.

Novgorod and Muscovy

As early as the 11th century the Novgorodians had occasionally penetrated into Siberia; but the fall of the Novgorod republic and the loss of its north-eastern dependencies checked the advance of the Russians across the Urals. On the defeat of an insurrection, many who were unwilling to submit to the iron rule of Moscow made their way to the settlements of an entrepreneur Stroganov in Perm, and tradition has it that, in order to get rid of his guests, Stroganov suggested to their chief, Yermak, that he should cross the Urals into Siberia, promising to help him with supplies of food and arms.

Yermak and the Cossacks

Yermak entered Siberia in 1580 with a band of 1636 men, following the Tagil and Tura rivers. Next year they were on the Tobol, and 500 men successfully laid siege to Isker, the residence of Khan Kuchum, in the neighbourhood of what is now Tobolsk. Kuchum fled to the steppes, abandoning his domains to Yermak, who, according to tradition, purchased by the present of Siberia to tsar Ivan IV his own restoration to favour.

Yermak drowned in the Irtysh in 1584 and his Cossacks abandoned Siberia. But new bands of hunters and adventurers poured every year into the country, and were supported by Moscow. To avoid conflicts with the denser populations of the south, they preferred to advance eastwards along higher latitudes; meanwhile Moscow erected forts and settled labourers around them to supply the garrisons with food. Within eighty years the Russians had reached the Amur and the Pacific Ocean. This rapid conquest is accounted for by the circumstance that neither Tatars nor Turks were able to offer any serious resistance.

Imperial Russian Expansion

The main treasure to attract Cossacks to Siberia was fur of sables, foxes and ermines. From most of the exploration expeditions, the travelers brought lots of furs. Local people, submitting to Russia, received a defence by Cossacs from the southern nomads. In exchange they were obliged to pay yasak (ясак, a tax) in form of furs. There was a set of yasachnaya roads, used to transport yasak to Moscow.

A number of peoples mentioned below showed opened resistance to Russians. Others submitted and even requested to be subordinated, though sometimes they later refused to pay yasak, or not admited the Russian authority. There are evidences of collaboration and assimilation of Russians with the local peoples in Siberia though the more they advanced to the East, the less local people were developed and the more resistance they offered. The most resisting peoples were Koryak and Chukchi (in Chukotka peninsula), the latter still being in the stone age.

In 1607–1610 the Tungus fought strenuously for their independence, but were subdued about 1623. In 1628 the Russians reached the Lena, founded the fort of Yakutsk in 1637, and two years later reached the Sea of Okhotsk at the mouth of the Ulya river. The Buryats offered some opposition, but between 1631 and 1641 the Cossacks erected several palisaded forts in their territory, and in 1648 the fort on the upper Uda River beyond Lake Baikal. In 1643 Vassili Poyarkov's boats descended the Amur, returning to Yakutsk by the Sea of Okhotsk and the Aldan River, and in 1649–1650 Yerofey Khabarov occupied the banks of the Amur. The resistance of the Chinese, however, obliged the Cossacks to quit their forts, and by the Treaty of Nerchinsk (1689) Russia abandoned her advance into the basin of the river. In 1852 a Russian military expedition under Muraviev explored the Amur, and by 1857 a chain of Russian Cossacks and peasants were settled along the whole course of the river. The accomplished fact was recognised by China in 1857 and 1860 by a treaty.

In the same year in which Khabarov explored the Amur (1648) the Cossack Dezhnev, starting from the Kolyma River, sailed round the north-eastern extremity of Asia through the strait which was rediscovered and described eighty years later by Bering (1728). Cook in 1778, and after him, La Pérouse, settled definitively the broad features of the northern Pacific coast.

Although the Arctic Ocean had been reached as early as the first half of the 17th century, the exploration of its coasts by a series of expeditions under Dmitry Ovtsyn, Fyodor Minin, Vasili Pronchishchev, Lasinius and Laptev—whose labours constitute a brilliant page in the annals of geographical discovery—was begun only in the 18th century (1735–1739).

Scientists in Siberia

The scientific exploration of Siberia, begun in the period 1733 to 1742 by Messerschmidt, Gmelin, and De L'isle de la Croyere, was followed up by Muller, Fischer and Georgi. Pallas, with several Russian students, laid the first foundation of a thorough exploration of the topography, fauna, flora and inhabitants of the country. The journeys of Christopher Hansteen and Georg Adolf Erman (1828ff) were a most important step in the exploration of the territory. Humboldt, Ehrenberg and Gustav Rose also paid in the course of these years short visits to Siberia, and gave a new impulse to the accumulation of scientific knowledge; while Ritter elaborated in his Asien (1832–1859) the foundations of a sound knowledge of the structure of Siberia. T von Middendorff's journey (1843–1845) to north-eastern Siberia—contemporaneous with Castrén's journeys for the special study of the Ural-Altaic languages—directed attention to the far north and awakened interest in the Amur, the basin of which soon became the scene of the expeditions of Akhte and Schwarz (1852), and later on (1854ff) of the Siberian expedition to which we owe so marked an advance in our knowledge of East Siberia.

The Siberian branch of the Russian Geographical Society was founded at the same time at Irkutsk, and afterwards became a permanent centre for the exploration of Siberia; while the opening of the Amur and Sakhalin attracted Maack, Schmidt, Glehn, Radde and Schrenck, whose works on the flora, fauna and inhabitants of Siberia have become widely known.

Early settlement

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the Russians that migrated into Siberia were hunters, and those who escaped from the Central Russia: fugitive peasants in search for life free of serfdom, fugitive convicts and old beleivers. The new settlements of Russians and the existing local peoples required defence from nomads, for which forts were found. This way were found forts of Tomsk and Berdsk.

In the begining of the eighteenth century the nomads threat weakened, thus the region became more and more populated, normal civic life established in the cities.

Established life

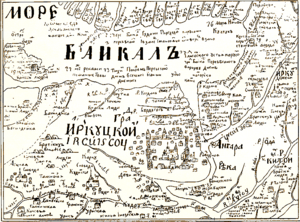

In the eighteenth century in Siberia, a new administrative region (губерния, guberniya, similar to contemporary Federal Subjects)was formed with Irkutsk, then in the nineteenth century the territory was seveal times re-divided with creation of new guberniyas: Tomsk (with center in Tomsk) and Yenisei (Yeniseysk, later Krasnoyarsk).

In the 1730 the first large industrial project, the metallurgical production found by Demidov family, gave birth to the city of Barnaul. Later the enterprise organized social institutions like library, club, thearte. Pyotr Semenov-Tyan-Shansky, who stayed in Barnaul in 1856-1857 wrote "The richness of mining engineers of Barnaul expressed not merely in their housholds and clothes, but more in their educational level, knowledge of science and literature. Barnaul was undoubtly the most cultured place in Siberia, and I've called it Siberian Athenes, leaving Sparta for Omsk".

The same events took place in other cities: public libraries, museums of local lore, colleges, theatres. Though, the first university in Siberia was opened as late as 1880 in Tomsk.

Siberian peasant more than Russian relied on his own force and abilities, had to fight against the harder climate and hadn't a help to expect. Lack of serfdom and landlords also contributed to his independent character. Unlike the Russian peasants, Siberians had no problems with land, thus were able to use a piece intensively for several years in a row, then to leave it fallow for a long time and plow up the next piece. Peasant used to eat a lot, while in the Central Russia he cared a lot to moderate the family's appetite. Leonid Blummer noted that alcohol drinking culture differed a lot, that Siberian peasants though drinking frequently, always did it gently: For a Siberian vodka isn't a wonder, unlike a Russian peasant, which, having reached it after all this time, is ready to drink a sea. The houses, according to the travellers' notes, were absolutely unlike those usual Russian izbas: the houses were big, often two-floored, the ceilings were high, the walls were covered with boards and painted with oil-paint.

Decembrists and other exiled

Siberia was a good place to exile for political reasons: it was far from any foreign country. A Saint Petersburg citizen wouldn't wish to escape in vast Sibrian countryside for volya (Russian for will and freedom) as the peasants and criminals did. Even the cities, Irkutsk, Omsk, Krasnoyarsk, lacked that intensive social life and luxurous high life of the capital.

About 80 persons involved in the Decembrist revolt were sentenced to obligatory work in Siberia and perpetual settlement here. 11 wifes followed them and settled near the labour camps. In their memoirs, they noted the benevolence and the prosperity of rural Siberians and severe treatment by the soldiers and officers.

Travelling through Siberia, I was wondered and fascinated at every step by that cordiality and hospitality, that I met everywhere. I was fascinated by the richness and the abundance, with which the people live until today (1861), but that time there was even more expanse in evertything. Especially the hospitality was developed in Siberia. Everywhere we were received like being in friendly countries, everywhere we were fed well, and when I asked how much I owed them, they didn't want to take anything, saying "Put a candle to the God".

...Siberia is extremely rich country, the land is ususually fruitful, and a few work is needed to get a plentiful harvest.

Polina Annenkova, Notes of a Decembrist's Wife

A number of decembrists died of diseases, some suffered psychological shock and even went out of theri mind.

After completing the term of obligatory work, they were sentenced to settle in specific small towns and villiages. There, some started doing business, which was well permitted. Only several years later, in 1840s they were allowed to move to big cities or to settle anywhere in Siberia. Only in 1856, 31 years after the revolt, in honour of the coronation Alexander II pardoned and restituted the decembrists.

Living in the cities of Omsk, Krasnoyarsk and Irkutsk, the decembrists contributed a lot to the social life and culture. In Irkutsk, their houses are now the museums. In many places, memorial tablets with names are installed.

Yet, there were exeptions: Vladimir Raevskiy was arested for participation in decembrists' circles in 1822, and in 1828 was exiled to Olonki villiage near Irkutsk. There he married and had 9 children, traded with bread and founded a school for children and adults to teach arythmetics and grammar. Being pardoned by Alexander II, he visited his native town, but returned back to Olonki.

Despite of the central authorities' wishes, the exiled revolutioners unlikely felt outcast in Siberia. Quite the contrary, Siberians having lived all the time on their own, "didn't feel tenderness" to the authorities. In many cases, the exiled were cordially received and got paid positions.

Fyodor Dostoevsky was exiled to katorga near Omsk and to military service in Semipalatinsk. In the service he also had to make trips for Barnaul and Kuznetsk.

Anton Chekhov wasn't exiled, but in 1890 made a trip on his own to Sakhalink Isle through Siberia and visited a katorga there. In his trip, he visited Tomsk, speaking disapprovingly about it, then Krasnoyarsk and called it "the most beautiful Siberian city". He noted that despite being more a place of criminal rahter than political exile, the moral atmosphere was much better: he didn't face any case of theft. Blummer, suggested to prepare a gun, but his attendant replied: What for?! We are not in Italy, you know. Chekhov observed that besides of the evident prosperity, there was an urgent demand for cultural development.

Trans-Siberian Railway

- For more information, see the article on the Trans-Siberian Railway

The first projects of railroads in Siberia emerged since the creation of the railroad Moscow-St. Petersburg. One of the first was Irkutsk-Chita project, intended to connect the former to Amur river and, consequently, to the Pacific Ocean.

But before 1880 the central government almost not responded to many of such projects, because of weakness of Siberian enterprises, fear to allow Siberian territories integrate with the Pacific region rather than with Russia, and thus to get under influence of America and Britain. The heavy and clumsy bureaucracy, and the fear of financial risk also contributed to the inaction: the financial system always underestimated the effects of railway, assuming that it would take only the existing traffic.

Namely the fear to lose Siberia convinced Alexander III of Russia in 1880 to make a decision to build the railway. The construction started in 1891.

Trans-Siberian gave a great boost to Siberian agriculture, allowing large export to the Central Russia and European countries. It pushed not only the closest to the railway territories, but also those, connected with meridional rivers, like Ob (Altai) and Yenisei (Minusinsk and Abakan region).

Siberian agriculture exported a lot of cheap grain towards the West. The agriculture in Central Russia was still under pressure of serfdom, formally cancelled in 1861.

Thus, to defend it and to prevent a possible social destabilization, in 1896 (when the eastern and western parts of the Trans-Siberian didn't close up yet), the government introduced Chelyabinsk tariff break (Челябинский тарифный перелом), a tariff barier for grain in Chelyabinsk, and a similar barrier in Manchuria. This measure changed the form of bread export: mills emerged in Altai, Novosibirsk and Tomsk, many farms switched to butter production. Since 1896 till 1913 Siberia exported averagely 30,643 thousand poods (501,932 tonnes) of bread (grain, flour) annually.

Stolypin's resettlement programme

The idea that Gulag and Soviet authorities enpopulated Sibeiria by forcibly, is a popular delusion. In fact, the real large settlement campaign was carried out under Nicholas II by Prime Minister Stolypin in 1906-1911.

The rural areas of Central Russia were overcrowded, while the East was still scarsely populated, even being fruitful. On May 10th, 1906, by the highest command of Tsar, agriculturists were granted a right to transfer, without any special permission or control, to the Asian territories of Russia, and to get there specially devoted land. A large advertizing campaign was conducted: 6 million copies of brochures and banners entitled "What does the resettlement give to peasants", "How do live the peasants in Siberia" were printed and distributed in rural areas. Special agitational trains, special transport trains were formed. The State gave loans to the resettlers for farm construction.

Not all the resettlers decided to stay, 17.8% migrated back. In total, more than 3 million people officially resettled to Siberia, and 750,000 came as foot-messengers. From 1897 to 1914 Siberian population increased by 73%, sown areas doubled.

The Civil war

By the time of the revolution Siberia was an agricultural province of Russia, with weak entrepeneur and industrial class. The intelligentsia had vague political ideas. Only 13% of the territory population lived in the cities and posessed some political knowledge. The lack of strong social difference, fewness of cities population and intellectuals led to uniting of formally different political parties under ideas of regionalism.

The anti-Bolsheviks forces failed to offer a united resistance. While Kolchak fought against the Bolsheviks intending to eliminate them in the capital of the Empire, the local Socialists-Revolutioners and Mensheviks tried to sign a peaceful treaty with Bolsheviks, on terms of independence. The foreign allies, though being able to make a decisive effort, preferred to stay neutral, also Kolchak himself rejected the offer of help from Japan.

- For more detailed chronology of the civil war in Siberia, see article on Aleksandr Kolchak

After a series of defeats in the Central Russia, Kolchak's forces had to retreat to Siberia. The resistance of SR-s and waning support from the allies, the Whites had to evacuate from Omsk to Irkutsk, and finally Kolchak resigned under pressure of SR-s, who soon submited to Bolsheviks.

1920s and 1930s

By the 1920s the agriculture in Siberia was in deterioration: with the large of immigrants, land was used very intensively, which led to exhaustion and frequent bad harvest. The agriculture wasn't destroyed by the civil war, but the disorganization of the exports destroyed the food industry and reduced the peasants' incomes. Furthermore, prodrazvyorstka and then the natural food tax contributed to growing discontent. In 1920-1924 there was a number of anti-communistic riots in rural areas, with up to 40 thousand people involved. Both old Whites (Cossacks) and old "Reds" partisans, who earlier fought against Kolchak, the marginals, who were the major force of the Communists, took part in the riots. According to a survey of 1927 in Irkutsk Oblast, the peasants openly said they'd participate in anti-soviet rebel and hoped for the foreign help. It should be noticed also that the Soviet authorities declared by a special order the KVZhD builders and workers enemies of people.

The youth, that had socialized in the age of war, was highly militarized, and the Soviet government pushed the further military propaganda by Komsomol. There are many documented evidences of "red banditism", especially in the countryside, such as desecration of churches and christian graves, and even murders of priests and beleivers. Also in many cases a Komsomol activist or an authority representative, speaking with a person opposed to the Soviets, got angry and killed him/her and anybody else. The Party faintly counteracted this.

In 1930s, the Party started the collectivization, which automatically put the "kulak" label on the well-off families living in Siberia for a long time. Naturally, raskulachivanie applied to everyone who protested. From the Central Russia many families were exiled in low-populated, forest or swampy areas of Siberia, but those who lived here, had either to escape anywhere, or to be exiled in the Northern regions (such as Evenkia, Khantia-Mansia, North of Tomsk Oblast). Collectivization destroyed the traditional and most effective stratum of the peasants in Siberia and the natural ways of development, and it's consequences are still persisting.

In the cities, during the NEP and later, the new authorities, driven by the romantic socialistic ideas made attempts to build new socialistic cities, according to the fashionable constructivism movement, but after all have left only numbers of square houses. For example, the Novosibirsk theatre was initially designed in pure constructivistic style. It was an ambitious project of exiled architects. In the mid-1930s with introduction of new classicism, it was significantly redesigned.

After the Trans-Siberian was built, Omsk soon became the largest Siberian city, but in 1930s Soviets favoured Novosibirsk.

In 1930s, Gulag established a large network of labour camps in Siberia.

World War II

In 1941, many enterprizes and people were evacuated into Siberian cities by railroads. In urgent need for ammunition and military equipment, they started working right after being unloaded near the stations. The workshops' buildings were built simultaneously with work.

Most of the evacuated enterprizes remained at their new sites after the war. They increased industrial production in Siberia to a great extend, and became constitutive for many cities, like Rubtsovsk. The most Eastern city to receive them was Ulan-Ude, since Chita was considered dangerously close to China and Japan.

On August 28, 1941 the Supreme Soviet stated and order "About the Resettlement of the Germans of Volga region", by which many of them were deported into different rural areas of Kazakhstan and Siberia.

By the end of war, thousands of captive soldiers and officers of German and Japanese armies were sentenced to several years of work in labour camps in all the regions of Siberia, including. These camps were directed by a different administration than Gulag. Though, Soviet camps hadn't a purpose to lead prisoners to death, the death rate was significant, especially in winters. The range of works differend from vegetable farming to construction of Baikal Amur Mainline.

Industrial expansion

The second half of the XX century also saw the beginning of substantial exploitation of Siberia's plentiful natural resources. Mines developed to ship material west, and many industrial towns also grew up to make use of the resources.

The most famous projects include Baikal Amur Mainline, the cascade of hydroelecric stations was built on Angara river, a project similar to Tennessee River in the US. The powerstations allowed to create large productions, such as alluminium plant in Bratsk, rare-earth mining in Angara basin, timber industry. The price of electricity in Angara basin is the lowest in Russia. The settlement is not finished yet, the Boguchany hydroelectric power station and a set of enterprises based on it's energy are yet to be finished.

The underside of this development is the ecological damage due to low standards of production and excessive sizes of dams (the bigger projects were favoured by the industrial authorities that received more funding), the increased humidity that sharpened the already hard climate. A project of another powerstation on Katun river in Altai mountains in the 1980s was cancelled thanks to public protests.

There is a number of military-oriented centers like the NPO Vektor and closed cities like Seversk. By the end of 1980s a large portion of industrial production of Omsk and Novosibirsk (up to 40%) was composed by military and aviation plants. The collapse of state-funded military orders aggravated the consequences economic crisis.

The Siberian Branch of Russian Academy of Sciences unites a lot of research institutes in the biggest cities, the biggest being the Budker Institute of Nuclear Physics in Akademgorodok (a scientific town) near Novosibirsk. Other scientific towns or just districts composed by research institutes, also named Akademgorodok, are in the cities of Tomsk, Krasnoyarsk and Irkutsk. These sites are the centers of the newly developed IT industry, especially in that of Novosibirsk, nicknamed Silicon Taiga, and in Tomsk.

A number of Siberian-based companies extended their businesses of various consumer producst to meta-regional and All-Russian level. Various Siberian artists and industries, have created their communities that are not centalized on Moscow anymore, like the Idea (annual low-budged ads festival), Golden Capital (annual prize in architecture).

Future prospects

Before the completion of the Chita-Khabarovsk highway, the Transbaikalia was a dead end for automobile transport. The constructed road at first will be used for transit, but will boost settlement and expansion in the scarsely populated regions of Chita and Blagoveshchensk.

Transport network development will continue to define the directions of Siberian regional development. The nearest project to be performed is the finalizing of the railroad branch to Yakutsk. Another large project, proposed yet in XIX century as a northern variant of Transsiberian railroad, is Northern-Siberian Railroad between Nizhnevartovsk, Belyi Yar, Lesosibirsk and Ust-Ilimsk. The Russian Railroads instead suggest an ambitious project of a railway to Magadan, Chukotka penunsula and then the supposed Bering Straight Tunnel to Alaska.

While the Russians continue to emigrate from Siberian federal district to the western regions, the Siberian cities attract labour (illegal as well) from the Central Asian republics and from China. While the natives are aware of the situation, in the Western regions are popular the myths about thousands and millions of Chinese living in the Transbaikalia and the Far East. Thus it is not uncommon in the Russian society, especially to the West of Urals, to be anxious about a supposed Chinese annexation of the South-East Siberia.

References

- Зуев А. С. Русская политика в отношении аборигенов крайнего Северо-Востока Сибири (XVIII в.) // Вестник НГУ. Серия: История, филология. Т. 1. Вып. 3: История / Новосиб. гос. ун-т. Новосибирск, 2002. C. 14–24.

Zuyev A. S. Russian Policy Regarding to the Aborigines of the Extreme North-East of Russia (XVIII century) // Vestnik NGU. History and Philosophy, vol. 1, issue 3: History / Novosibirsk State University, 2002. P. 14-24. Online version - Скобелев С. Г. Межэтнические контакты славян с их соседями в Средней Сибири в XVII-XIX вв. Skobelev S. G. Intraethnic Contacts of Slavs with Their Neibours in the Central Siberia in XVII-XIX centuries. ? Online version

- Зуев А. С. «Немирных чукчей искоренить вовсе…» // Родина, №1, 1998.

Zuyev A. S. “Unpeaceful chukchi to be extirpated at all...” // Rodina, #1, 1998. Online version - Семенов-Тян-Шанский П.П. Мемуары. Т. 2. М., 1946. С. 56-57, 126. Semyonov-Tyan-Shansky P. P. Memoirs, vol. 2. Moscow, 1946. P. 56-57, 126.

- ^ A large article that quotes Chekhov and Blummer on Siberia:

Старцев А. В. Homo Sibiricus // Земля Сибирь. Новосибирск. 1992. № 5–6.

Startsev A. V. Homo Sibiricus // Zemlya Sibir'. Novosibirsk, 1992. #5-6. - Анненкова П. Е., Записки жены декабриста. Онлайновая версия текста Воспроизводится по: «Своей судьбой гордимся мы». Иркутск, Восточно-Сибирское книжное издательство, 1973 г. Annenkova P. Notes of a Decembrist's Wife. Online version reproduced by “We Are Proud of Our Destiny”, Irkutsk, Vostochno-Sibirskoye izdatelstvo, 1973.

- Based on a chapter of: Problem Regions of Resourse Type: Economical Integration of European North-East, Ural and Siberia. / Managing editors: V. V. Alexeev, M. K. Bandman, V. V. Kuleshov — Novosibirsk, IEIE, 2002. ISBN 5-89665-060-4

- Храмков А. А. Железнодорожные перевозки хлеба из Сибири в западном направлении в конце XIX — начале XX вв. // Предприниматели и предпринимательство в Сибири. Вып.3: Сборник научных статей. Барнаул: Изд-во АГУ, 2001.

Khramkov A. A. Railroad Transportation of Bread from Siberia to the West in the Late XIX — Early XX Centuries. // Entrepreneurs and Business Undertakings in Siberia. 3rd issue. Collection of scientific articles. Barnaul: Altai State University publishing house, 2001. ISBN 5-7904-0195-3 - Section is based on: И. Воронов. Столыпин и русская Сибирь / Экономика и жизнь (Сибирь), №189, 19.05.2003. I. Voronov. Stolypin and Russian Siberia / Economics and Life (Siberia), #189, 19/05/2003. Online version

- Шиловский М.В. Политические процессы в Сибири в период социальных катаклизмов 1917-1920 гг. — Новосибирск, ИД "Сова", 2003.

Shilovsky M. V. The Political Processes in Siberia in the Period of Social Cataclysms of 1917-1920s. — Novosibirsk, "Sova" publishing house, 2003. ISBN 5-87550-150-2 - Шиловский М. В. Консолидация "демократической" контрреволюции в Сибири весной-летом 1919 г. // Актуальные вопросы истории Сибири. Вторые научные чтения памяти проф. А.П. Бородавкина: Материалы конф. Барнаул: Изд-во Алт. ун-та, 2000. 421 с.

Shilovsky M. V. Consolidation of the "Democratic" Counter-Revolution in Siberia in the Spring-Summer 1919 // Questions of Siberian History of Current Importance. The Second Scientific Conference devoted to prof. A. P. Borodavkin. — Barnaul, Altai State University, 2000. ISBN 5-7904-0149-x - Михалин В. А. Из истории изучения сельского хозяйства Сибири в начале 1920-х гг. (записка Н. Я. Новомбергского) // Сибирь в XVII–XX веках: Проблемы политической и социальной истории: Бахрушинские чтения 1999–2000 гг.; Межвуз. сб. науч. тр. / Под ред. В. И. Шишкина. Новосиб. гос. ун-т. Новосибирск, 2002.

Mikhalin V. A. From the History of Siberian Agriculture Studies in the Early 1920-s (N. Ya. Novombergskiy's Note) // Siberia in the XVII-XX centuries: Problems of the Political and Social History. — Novosibirsk State University, Novosibirsk, 2002. - Шишкин В. И. Партизанско-повстанческое движение в Сибири в начале 1920-х годов // Гражданская война в Сибири. — Красноярск, 1999. C. 161–172.

Shishkin V. I. Partisan-Rebellious Movement in Siberia in the Early 1920s //The Civil War in Siberia. — Krasnoyarsk, 1999. P. 161-172. - ^ Исаев В. И. Военизация молодежи и молодежный экстремизм в Сибири (1920-е — начало 1930-х гг.) // Вестник НГУ. Серия: История, филология. Т. 1. Вып. 3: История / Новосиб. гос. ун-т. Новосибирск, 2002.

Isayev V. I. Militarization of the Youth and Youth Extremism in Siberia (1920s - early 1930s). // Vestnik NGU. History and philosophy series. Vol. 1, Issue 3: History. / Novosibirsk State University, Novosibirsk, 2002. - Карлов С. В. К вопросу о ликвидации кулачества в Хакасии (начало 30-х гг.) // Актуальные вопросы истории Сибири. Вторые научные чтения памяти проф. А.П. Бородавкина: Материалы конф. Барнаул: Изд-во Алт. ун-та, 2000. 421 с.

Karlov S. V. On the Liquidation of Kulaks in Khakassia (Early 1930s) // Questions of Siberian History of Current Importance. The Second Scientific Conference devoted to prof. A. P. Borodavkin. — Barnaul, Altai State University, 2000. ISBN 5-7904-0149-x

External links

- "Sibirskaya Zaimka" — an internet journal of scientific publications on the Siberian history (in Russian, with a link to an online translated version)