| Revision as of 07:13, 12 January 2015 view sourceAnomieBOT (talk | contribs)Bots6,573,980 edits Rescuing orphaned refs ("cruk" from rev 641940581)← Previous edit | Revision as of 06:51, 15 January 2015 view source Vernekar8 (talk | contribs)16 edits Removed ancillary information about ayurveda and placed it under the subheading of toxic metals.Next edit → | ||

| Line 12: | Line 12: | ||

| By the ], Ayurvedic practitioners developed a number of medicinal preparations and surgical procedures for the treatment of various ailments.<ref name="Dwivedi&Dwivedi07">Dwivedi & Dwivedi (2007)</ref> Practices that are derived from Ayurvedic medicine are regarded as part of ].<ref name="nccam1">{{cite journal |url= http://nccam.nih.gov/news/newsletter/2006_winter/ayurveda.htm |title=A Closer Look at Ayurvedic Medicine |journal=Focus on Complementary and Alternative Medicine |volume=12 |issue=4 |date=Fall 2005 – Winter 2006 |publisher=] (NCCAM). ] (NIH) |location=Bethesda, Maryland |archiveurl= https://web.archive.org/web/20061209114559/http://nccam.nih.gov/news/newsletter/2006_winter/ayurveda.htm |archivedate= 2006-12-09 }}</ref> | By the ], Ayurvedic practitioners developed a number of medicinal preparations and surgical procedures for the treatment of various ailments.<ref name="Dwivedi&Dwivedi07">Dwivedi & Dwivedi (2007)</ref> Practices that are derived from Ayurvedic medicine are regarded as part of ].<ref name="nccam1">{{cite journal |url= http://nccam.nih.gov/news/newsletter/2006_winter/ayurveda.htm |title=A Closer Look at Ayurvedic Medicine |journal=Focus on Complementary and Alternative Medicine |volume=12 |issue=4 |date=Fall 2005 – Winter 2006 |publisher=] (NCCAM). ] (NIH) |location=Bethesda, Maryland |archiveurl= https://web.archive.org/web/20061209114559/http://nccam.nih.gov/news/newsletter/2006_winter/ayurveda.htm |archivedate= 2006-12-09 }}</ref> | ||

| ⚫ | Concerns have been raised about Ayurvedic products; ] studies showed that up to 20% of Ayurvedic U.S. and Indian-manufactured ]s sold through internet contained toxic levels of heavy metals such as ], ], and ].<ref name="Valiathan06">{{cite journal|last=Valiathan|first=MS|title=Ayurveda: putting the house in order |journal=Current Science |volume=90 |issue=1|pages=5–6|year=2006|publisher=]|url=http://www.currentscience.ac.in/Downloads/article_id_090_01_0005_0006_0.pdf|format=pdf}}</ref><ref name="Saper2008">{{cite journal |author1=Saper RB |title=Lead, mercury, and arsenic in US- and Indian-manufactured medicines sold via the internet |journal=JAMA |volume=300 |issue=8 |pages=915–923 |year=2008 |pmid=18728265 |doi=10.1001/jama.300.8.915 |pmc=2755247 |author2=Phillips RS |author3=Sehgal A |last4=Khouri |first4=N |last5=Davis |first5=RB |last6=Paquin |first6=J |last7=Thuppil |first7=V |last8=Kales |first8=SN|display-authors=2 }}</ref> | ||

| == Eight components of Ayurveda == | == Eight components of Ayurveda == | ||

| Line 151: | Line 151: | ||

| ==Use of toxic metals== | ==Use of toxic metals== | ||

| ⚫ | Concerns have been raised about Ayurvedic products; ] studies showed that up to 20% of Ayurvedic U.S. and Indian-manufactured ]s sold through internet contained toxic levels of heavy metals such as ], ], and ].<ref name="Valiathan06">{{cite journal|last=Valiathan|first=MS|title=Ayurveda: putting the house in order |journal=Current Science |volume=90 |issue=1|pages=5–6|year=2006|publisher=]|url=http://www.currentscience.ac.in/Downloads/article_id_090_01_0005_0006_0.pdf|format=pdf}}</ref><ref name="Saper2008">{{cite journal |author1=Saper RB |title=Lead, mercury, and arsenic in US- and Indian-manufactured medicines sold via the internet |journal=JAMA |volume=300 |issue=8 |pages=915–923 |year=2008 |pmid=18728265 |doi=10.1001/jama.300.8.915 |pmc=2755247 |author2=Phillips RS |author3=Sehgal A |last4=Khouri |first4=N |last5=Davis |first5=RB |last6=Paquin |first6=J |last7=Thuppil |first7=V |last8=Kales |first8=SN|display-authors=2 }}</ref> | ||

| Rasa shastra, the practice of adding metals, minerals or gems to herbs, may include toxic heavy metals such as lead, ] and arsenic.<ref name="Saper2008"/> Adverse reactions to herbs due to their pharmacology are described in traditional Ayurvedic texts, but the practitioners are reluctant to admit that herbs could be toxic and that reliable information on herbal toxicity is not readily available; there is a communication gap between modern medicine practitioners and Ayurvedic practitioners.<ref name="Urmila2008">{{cite journal | author1=Urmila, T. |author2=Supriya, B. |year=2008 |title=Pharmacovigilance of ayurvedic medicines in India | journal=Indian Journal of Pharmacology | volume=40 | issue=S1 |pages =10–12 |url = http://www.bioline.org.br/request?ph08015}}</ref> | Rasa shastra, the practice of adding metals, minerals or gems to herbs, may include toxic heavy metals such as lead, ] and arsenic.<ref name="Saper2008"/> Adverse reactions to herbs due to their pharmacology are described in traditional Ayurvedic texts, but the practitioners are reluctant to admit that herbs could be toxic and that reliable information on herbal toxicity is not readily available; there is a communication gap between modern medicine practitioners and Ayurvedic practitioners.<ref name="Urmila2008">{{cite journal | author1=Urmila, T. |author2=Supriya, B. |year=2008 |title=Pharmacovigilance of ayurvedic medicines in India | journal=Indian Journal of Pharmacology | volume=40 | issue=S1 |pages =10–12 |url = http://www.bioline.org.br/request?ph08015}}</ref> | ||

Revision as of 06:51, 15 January 2015

| This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. You can assist by editing it. (December 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Ayurveda (Sanskrit Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), "life-knowledge"; English pronunciation /ˌaɪ.ərˈveɪdə/) or Ayurvedic medicine is a system of Hindu traditional medicine of Vedic tradition native to the Indian subcontinent, and a form of alternative medicine. Some of the oldest known Ayurvedic texts include the Suśrutha Saṃhitā, Charaka Saṃhitā. These Sanskrit texts are among the foundational and formally compiled works of Ayurveda.

By the medieval period, Ayurvedic practitioners developed a number of medicinal preparations and surgical procedures for the treatment of various ailments. Practices that are derived from Ayurvedic medicine are regarded as part of complementary and alternative medicine.

Eight components of Ayurveda

In classical Sanskrit literature, Ayurveda was called "the science of eight components" (Sanskrit aṣṭāṅga अष्टांग), a classification that became canonical for Ayurveda:

- Kayachikitsa (General medicine): "cure of diseases affecting the body".

- Kaumāra-bhṛtya and Bala Roga : "treatment of children".

- Shalya tantra: surgical techniques.

- Śālākya-tantra (Ophthalmology): cure of diseases of the teeth, eye, nose or ear etc.

- Bhuta-vidya deals with the causes, which are directly not visible and not explained directly from tridosha.: pertaining to micro-organisms or spirits.

- Agada-tantra : Gada means Poison. "doctrine of antidotes"

- Rasayana-tantra (Geriatrics)/(Anti Agings) : Doctrine of Rasayana/Rejuvenation.

- Vajikarana tantra (Aphrodisiacs): deals with healthy and desired progeny.

Principles and terminology

There are two ways in which to approach Ayurvedic principles and terminology: one may either focus on the historical foundation (as evidenced in the oldest Ayurvedic texts) or, alternatively, a description may take an ethnographic approach and focus on the forms of traditional medicine prevalent across India today.

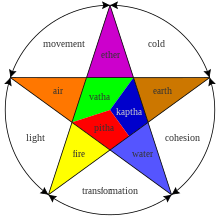

Much like the medicine of classical antiquity, Ayurveda has historically taken the approach of enumerating bodily substances in the framework of the five classical elements (Sanskrit panchabhuta, viz. earth, water, fire, air and ether. Moreover, Ayurveda names seven basic tissues (dhatu). They are plasma (rasa), blood (rakta), muscles (māmsa), fat (meda), bone (asthi), marrow (majja), and semen (shukra).

Further information: MahābhūtaAyurveda states that a balance of the three elemental substances, the Doshas, equals health, while imbalance equals disease. There are three doshas: Vata, Pitta and Kapha. One Ayurvedic theory states that each human possesses a unique combination of these doshas which define this person's temperament and characteristics. Each person has a natural state, or natural combination of these three elements, and should seek balance by modulating their behavior or environment. In this way they can increase or decrease the doshas they lack or have an abundance of them respectively. Another view present in the ancient literature states that dosha equality is identical to health, and that persons with imbalance of dosha are proportionately unhealthy, because they are not in their natural state of balance. Prakriti is one of the most important concepts in Ayurveda.

Further information: DoshaIn Ayurvedic theory, there are 20 qualities or characteristics (guṇas), which are inherent in all substances. They can be arranged in ten pairs of antonyms: heavy/light, cold/hot, unctuous/dry, dull/sharp, stable/mobile, soft/hard, non-slimy/slimy, smooth/coarse, minute/gross, viscous/liquid.

Further information: GunaEnsuring the proper functions of channels (srotas) that transport fluids is one part of Ayurvedic treatment, because a lack of healthy channels is thought to cause diseases. Practitioners treat patients with massages using oils and Swedana (fomentation) to open up these channels.

Hinduism and Buddhism have had an influence on the development of many of Ayurveda's central ideas. Balance is emphasised; suppressing natural urges is considered unhealthy and claimed to lead to illness; to suppress sneezing, for example, may give rise to shoulder pain. However, people are also cautioned to stay within the limits of reasonable balance and measure when following nature's urges. For example, emphasis is placed on moderation of food intake, sleep, and sexual intercourse.

Practice

Ayurvedic doctors regard physical and mental existence as well as personality as a unit, each element having the capacity to influence the others. One of the fundamental aspects of Ayurvedic medicine is to take this holistic approach into account during diagnosis and therapy.

Diagnosis

Ayurveda has 8 ways of diagnosis. They are Nadi (Pulse), Mootra (Urine), Mala (Stool), Jihva (Tongue), Shabda (Speech), Sparsha (Touch), Druk (Vision), Aakruti (Appearance).

Ayurvedic practitioners approach diagnosis by using the five senses. Hearing is used to observe the condition of breathing and speech. The study of the lethal points or marman marma is of special importance.

Treatment and health protection

While two of the eight branches of classical Ayurveda deal with surgery (Śalya-cikitsā, Śālākya-tantra), contemporary Ayurvedic theory tends to emphasise that building a healthy metabolic system, attaining good digestion and proper excretion lead to vitality. Ayurveda also focuses on exercise, yoga, and meditation. To maintain health, a Sattvic diet can be prescribed to the patient.

Concepts of Dinacharya are followed in Ayurveda; dinacharya stresses the importance of natural cycles (waking, sleeping, working, meditation etc.) for a healthy living. Hygiene, too, is a central practice of Ayurvedic medicine. Hygienic living involves regular bathing, cleansing of teeth, skin care, and eye washing.

Natural medical substances used

Ayurveda stresses the use of plant-based medicines and treatments. Plant-based medicines are derived from roots, leaves, fruits, barks and seeds such as cardamom and cinnamon. William Dymock and co-authors summarized hundreds of plant-derived medicines in 19th century, along with the prevalent myth, stories, uses, microscopic structure, chemical composition, toxicology and commerce in British India. Some animal products may also be used, for example milk, bones, and gallstones. In addition, fats are used both for consumption and for external use. Minerals, including sulphur, arsenic, lead, copper sulfate and gold are also consumed as prescribed. This practice of adding minerals to herbal medicine is known as rasa shastra.

A variety of alcoholic beverages known as Madya are used in Ayurveda. It enhances Pitta dosha and mitigates Vatta and Kapha dosha. They are grouped by the raw material and fermentation process and classified as: sugar based, fruit based, cereal based, cereal base with herbs, fermentation of vinegar and tonic wines. Madya are used for various purposes including to cause purgation, improve digestion and taste, to create dryness and to produce looseness of joints. Ayurveda texts describe it as non-viscid, quick in action, enters into minute pores of the body and cleaning them, spreads quickly.

Purified opium the dried latex from the plant capsule is used in eight Ayurvedic preparation. It balances Vata and Kapha Doshas and enhance Pitta Dosha. Used for treatment of certain conditions of diarrhoea and dysentery, and also to increase the sexual and muscular powers and produce stupefaction of brain. But, sedative and pain-relieving properties of opium on the human organ was not considered for Ayurvedic treatment purposes. The use of Opium is not found in the ancient Ayurveda texts. Although no exact time is known, it is possible that that Opium was brought to India along with or before the Mohammedan conquest. The therapeutic usage of opium is first mentioned in Sarngadhara Samhita, a book on pharmacy written between 1300-1400 CE that was referred by physicians of Rajasthan in Western India, as ingredient of an aphrodisiac to delay seminal ejaculation.

The book Yoga Ratnakara written in 1700-1800 CE by an unknown author and popular in Maharashtra uses opium as an ingredient for a herbo-mineral composition for treatment of diarrhea.

In Bhaisajya Ratnavali, opium along with camphor is used in treatment of acute gastro-enteritis. In this drug, the respiratory depressant action of Opium was counteracted by the respiratory stimulant property of Camphor. Later books have included the narcotic property for use as analgesic pain reliever.

Cannabis Indica, a plant of Indian origin is not mentioned in the ancient Ayurveda books. Its use as medicine is first mentioned in Sarngadhara Samhita, a book on pharmacy written between 1300-1400 CE, for the treatment of diarrhea. Later, in Bhaisajya Ratnavali it has been used as ingredient in an aphrodisiac

Both oil and tar were used to stop bleeding. Traumatic bleeding was said to be stopped by four different methods: ligation of the blood vessel; cauterisation by heat; using different herbal or animal preparations locally which could facilitate clotting; and different medical preparations which could constrict the bleeding or oozing vessels. Various oils could be used in a number of ways, including regular consumption as a part of food, anointing, smearing, head massage, prescribed application to affected areas, and oil pulling. Also, liquids may be poured on the patient's forehead, a technique which is called shirodhara.

Panchakarma

Further information: PanchakarmaAccording to some experts, the practice of the cleansing practices known as panchakarma (Devanāgarī: पंचकर्म)) is a therapeutic way of eliminating toxic elements from the body. Panchakarma includes Vamana, Virechana, Basti, Nasya and Raktamokshana. Panchakarma is preceded by Poorva karma (Preparatory Step)and is followed by Paschat karma and Peyadi karma.

History

Origins of Ayurveda have been traced back to 5,000 BCE, originating as an oral tradition and later as medical texts, Ayurveda evolved from the Vedas. Ayurveda is a discipline of the upaveda or "auxiliary knowledge" in Vedic tradition. The origins of Ayurveda are also found in Atharvaveda. The samhita of the Atharvaveda itself contains 114 hymns or incantations for the magical cure of diseases. Charak has advised in his samhita that physicians should adhere to Atharva-Veda. There are various legendary accounts of the "origin of Ayurveda", e.g., that the science was received by Dhanvantari (or Divodasa) from Brahma. Tradition also holds that a lost text written by the sage Agnivesa, a student of the sage Bharadwaja, influenced the writings of Ayurveda.

Main Texts

There are three principal early texts on Ayurveda, they are Charaka Samhita, the Sushruta Samhita and the Bhela Samhita. The Sushruta Samhita is based on an original written during the 6th century BCE, this work was updated by 2nd century Buddhist scholar, Nagarjuna. The Charaka Samhita, written by Charaka, it is dated to the period of 6th century BCE. Bhela Samhita is also dated to a period of 6th century BCE, and attributed to the sage Atreya Punarvasu, who was the personal physician of King Nagnajit of Gandhara Kingdom. During early centuries of common era, Dridhabala had added updated Charaka Samhita. The Bower Manuscript, is also of special interest to historians due to its inclusion of Samhitas and its concepts in Central Asian Buddhism. A. F. R. Hoernle in his 1897 edition identified the scribe of the medical portions of the manuscript as a native of India, using a northern variant of the Gupta script, who had migrated and become a Buddhist monk in a monastery in Kucha. The Chinese pilgrim Fa Hsien (c. 337–422 AD) wrote about the health care system of the Gupta empire (320–550) and described the institutional approach of Indian medicine, also visible in the works of Charaka, who mentions a clinic and how it should be equipped.

Other early texts, mentioned alongside the Sushruta, Charaka and Bhela Samhita, are Agnivesha Samhita, Kasyapa Samhita and Harita Samhitas. The original edition of Agnivesha Samhita can be dated to 1500 BCE, it was written by Agnivesa and the text was later modified by Charaka. Kasyapa Samhita includes the treatise of Jivaka Kumar Bhaccha and it is dated a period of 6th century BCE. While Harita Samhita is dated to an earlier period, it is attributed to Harita, who was a disciple of Punarvasu Atreya. Some later texts includes Astanga nighantu (8th Century) by Vagbhata, Paryaya ratnamala (9th century) by Madhava, Siddhasara nighantu (9th century) by Ravi Gupta, Dravyavali (10th Century), Dravyaguna sangraha (11th century) by Cakrapanidatta, among others.

Illnesses portrayed

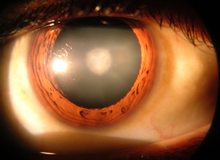

Underwood & Rhodes (2008) hold that this early phase of traditional Indian medicine identified "fever (takman), cough, consumption, diarrhea, dropsy, abscesses, seizures, tumours, and skin diseases (including leprosy)". Treatment of complex ailments, including angina pectoris, diabetes, hypertension, and stones, also ensued during this period. Plastic surgery, couching (a form of cataract surgery), puncturing to release fluids in the abdomen, extraction of foreign elements, treatment of anal fistulas, treating fractures, amputations, cesarean sections, and stitching of wounds were known. The use of herbs and surgical instruments became widespread.

Further development and spread

The field of Ayurveda flourished throughout the Indian Middle Ages; Dalhana (fl. 1200), Sarngadhara (fl. 1300) and Bhavamisra (fl. 1500) compiled works on Indian medicine.

The medical works of both Sushruta and Charaka were also translated into the Arabic language during the 8th century. The 9th-century Persian physician Rhazes was familiar with the text. The Arabic works derived from the Gupta-era Indian texts eventually also reached a European audience by the end of the medieval period.

In Renaissance Italy, the Branca family of Sicily and Gaspare Tagliacozzi (Bologna) are known to have been influenced by the Arabic reception of the surgical techniques of Sushruta.

British physicians traveled to India to observe rhinoplasty being performed using native methods; reports on Indian rhinoplasty were published in the Gentleman's Magazine in 1794. Instruments described in the Sushruta Samhita were further modified in Europe. Joseph Constantine Carpue spent 20 years in India studying local plastic surgery methods and, in 1815, was able to perform the first major rhinoplasty surgery in the western world, using the "Indian" method of nose reconstruction. In 1840 Brett published an article about this technique.

During the period of colonial British rule of India, the practice of Ayurveda was neglected by the British Indian Government, in favor of modern medicine. After Indian independence, there was more focus on Ayurveda and other traditional medical systems. By 2014, Ayurveda was part of the Indian National health care system, with state hospitals for Ayurveda established across the country; however, Ayurveda treatments were not always well integrated with others, especially in allopathic hospitals.

Current status

India

According to some sources, up to 80 percent of people in India use some form of traditional medicine, a category which includes Ayurveda.

In 1970, the Indian Medical Central Council Act which aimed to standardise qualifications for Ayurveda practitioners and provide accredited institutions for its study and research was passed by the Parliament of India. In India, over 180 training centers offer degrees in traditional Ayurvedic medicine. The Indian government supports research and teaching in Ayurveda through many channels at both the national and state levels, and helps institutionalise traditional medicine so that it can be studied in major towns and cities. The state-sponsored Central Council for Research in Ayurvedic Sciences (CCRAS) has been set up in order to do extensive research on the subject. To fight biopiracy and unethical patents, the Government of India, in 2001, set up the Traditional Knowledge Digital Library as repository of 1200 formulations of various systems of Indian medicine, such as Ayurveda, Unani and Siddha. The formulations come from over 100 traditional Ayurveda books.

The Central Council of Indian Medicine (CCIM) a statutory body established in 1971, under the Department of Ayurveda, Yoga and Naturopathy, Unani, Siddha and Homoeopathy (AYUSH), Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India, monitors higher education in Ayurveda. Many clinics in urban and rural areas are run by professionals who qualify from these institutes.

Nepal

About 75%-80% of the population of Nepal use Ayurvedic medicines. Ayurveda remains the most practiced form of medicine in the country.

Sri Lanka

The Sri Lankan tradition of Ayurveda is very similar to the Indian tradition. Practitioners of Ayurveda in Sri Lanka refer to texts on the subject written in Sanskrit, which are common to both countries. However, they do differ in some aspects, particularly in the herbs used.

The Sri Lankan government has established a Ministry of Indigenous Medicine (established in 1980) to revive and regulate the practice within the country. The Institute of Indigenous Medicine (affiliated to the University of Colombo) currently offers undergraduate, postgraduate, and MD degrees in the practice of Ayurveda Medicine and Surgery, and similar degrees in unani medicine.

There are currently 62 Ayurvedic Hospitals and 208 central dispensaries in the public system, and they served almost 3 million people (approximately 11% of Sri Lanka's total population) in 2010. In total there are currently approximately 20,000 registered practitioners of Ayurveda in the country.

According to the Mahavamsa, the ancient chronicle of Sinhalese royalty written in the sixth century A.D., King Pandukabhaya of Sri Lanka (reigned 437 BC to 367 BC) had lying-in-homes and Ayurvedic hospitals (Sivikasotthi-Sala) built in various parts of the country. This is the earliest documented evidence available of institutions dedicated specifically to the care of the sick anywhere in the world. Mihintale Hospital is the oldest in the world.

Outside the Subcontinent

Ayurveda is a system of traditional medicine developed during antiquity and the medieval period, and as such comparable to pre-modern Chinese and European systems of medicine. However, beginning in the 1960s, Ayurveda has begun to be advertised as "alternative medicine" in the Western world. Due to different laws and medical regulations in the rest of the world, the unregulated practice and commercialisation of Ayurvedic medicine has raised ethical and legal issues. In some instances, Ayurvedic practices or terminology have also been adapted specifically for Western consumption, notably in the case of "Maharishi Ayurveda" in the 1980s; in some cases, this has involved active fraud on the part of proponents of Ayurveda in an attempt to falsely represent the system as equal to the standards of modern medical research.

Baba Hari Dass was one of the early proponents who helped bring Ayurveda to the US in the beginning of 1970s. He taught classes in the three-dosha theory derived from the classic scriptures the Suśrutha Saṃhitā and the Charaka Saṃhitha, leading to the establishment of the Mount Madonna Institute, College of Ayurveda, Ayurveda World, and Ayurvedic pharmacy. He invited several notable Ayurvedic teachers (Vasant Lad, Sarita Shrestha, Ram Harsh Singh, and others). Michael Tierra, Ayurvedic practitioner, wrote: "The history of Ayurveda in North America will always owe a debt to the selfless contributions of Baba Hari Dass" (The way of Ayurvedic Herbs, Lotus Press, 2008, XIV).

In the United States, the practice of Ayurveda is not licensed or regulated by any state. Practitioners of Ayurveda may be licensed in other health care fields such as massage therapy or midwifery. A few states have approved schools teaching Ayurveda.

Efficacy

Although laboratory experiments suggest it is possible that some substances in Ayurveda might be developed into effective treatments, there is no evidence that any are effective in themselves. According to Cancer Research UK, no significant scientific evidence has shown effectiveness of Ayurvedic medicine for the treatment of any disease, although massage and relaxation are often beneficial for some cancer patients and there are indications from animal studies that some herbal products used might be explored further.

A review of the use of Ayurveda in cardiovascular disease concluded that the evidence is not convincing that any Ayurvedic herbal treatment is effective in the treatment of heart disease or hypertension, however, many herbs used by Ayurvedic practitioners show promise for future research and could be appropriate for larger randomized trials.

Research

In India, research in Ayurveda is undertaken by the statutory body of the Central Government, the Central Council for Research in Ayurveda and Siddha (CCRAS), through a national network of research institutes. In Nepal, National Ayurvedic Training and Research Centre (NATRC) conducts researches on medicinal herbs available in the country.

Use of toxic metals

Concerns have been raised about Ayurvedic products; U.S. studies showed that up to 20% of Ayurvedic U.S. and Indian-manufactured patent medicines sold through internet contained toxic levels of heavy metals such as lead, mercury, and arsenic. Rasa shastra, the practice of adding metals, minerals or gems to herbs, may include toxic heavy metals such as lead, mercury and arsenic. Adverse reactions to herbs due to their pharmacology are described in traditional Ayurvedic texts, but the practitioners are reluctant to admit that herbs could be toxic and that reliable information on herbal toxicity is not readily available; there is a communication gap between modern medicine practitioners and Ayurvedic practitioners.

According to a 1990 study on Ayurvedic medicines in India, 41% of the products tested contained arsenic, and 64% contained lead and mercury. A 2004 study found toxic levels of heavy metals in 20% of Ayurvedic preparations made in South Asia and sold in the Boston area; it concluded that Ayurvedic products posed serious health risks and should be tested for heavy-metal contamination. A 2008 study of more than 230 products found that approximately 20% of remedies (and 40% of rasa shastra medicines) purchased over the Internet from U.S. and Indian suppliers contained lead, mercury or arsenic. In 2012 the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) linked Ayurvedic drugs to lead poisoning, based on some cases where toxic materials were found in the blood of pregnant women who had taken Ayurvedic drugs.

Ayurvedic proponents believe that the toxicity of these materials is reduced through purification processes such as samskaras or shodhanas (for metals), similar to the Chinese pao zhi, although the Ayurvedic technique is more complex and may involve prayers as well as physical pharmacy techniques. However, these products have nonetheless caused severe lead poisoning and other toxic effects.

Due to these concerns, the government of India ruled that Ayurvedic products must specify their metallic content directly on the labels of the product. But in Current Science, a publication of the Indian Academy of Sciences, M. S. Valiathan noted that "the absence of post-market surveillance and the paucity of test laboratory facilities make the quality control of Ayurvedic medicines exceedingly difficult at this time."

"Most Ayurvedic products are marketed either for drug uses not approved by FDA or as dietary supplements. As such, consumers should understand that these products have not been approved by FDA before marketing". There is an import alert on some such products issued by the FDA since 2007 in order to prevent them entering the United States.

See also

- Bachelor of Ayurveda, Medicine and Surgery

- Bhaisajyaguru

- Clinical trials on Ayurvedic drugs

- Dosha

- Georgian folk medicine

- History of alternative medicine

- List of ineffective cancer treatments

- Siddha medicine

- Traditional Tibetan medicine

References

- Wells, John C. (2009). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary. London: Pearson Longman.

- Sharma, Amit K. (2009). "A Methodological Defence of Āyurveda". In Sinha, Anil Kishore (ed.). Bio-social Issues in Health. New Delhi, India: Northern Book Centre. pp. 129–132. ISBN 978-81-7211-225-7.

- ^ Dwivedi & Dwivedi (2007)

- "A Closer Look at Ayurvedic Medicine". Focus on Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 12 (4). Bethesda, Maryland: National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM). US National Institutes of Health (NIH). Fall 2005 – Winter 2006. Archived from the original on 9 December 2006.

- ^ Chopra 2003, p. 80

- Monier-Williams, A Sanskrit Dictionary (1899), s.v. "Āyurveda" OL 7164320M

- Poonam Bala. Medicine and Medical Policies in India: Social and Historical Perspectives. Lexington Books. p. 25.

- David Rakel, Nancy Faass. Complementary Medicine in Clinical Practice: Integrative Practice in American Healthcare. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 170.

- Benchmarks for training in traditional / complementary and alternative medicine (p. 23-25)

- ^ Birgit Heyn. Ayurveda: The Indian Art of Natural Medicine and Life Extension. Inner Traditions / Bear & Co. p. 17.

- The Healthy Living Space: 70 Practical Ways to Detoxify the Body and Home. Hampton Roads Publishing. p. 390.

- Langford, Jean (2002). Fluent Bodies: Ayurvedic Remedies for Postcolonial Imbalance. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University. p. http://books.google.com/books?id=C2-G-wGXqXAC&pg=PA87 87. ISBN 978-0-8223-2931-2.

- Clifford, Terry (2003). Tibetan Buddhist Medicine and Psychiatry. 42. Motilal Banarsidass Publications. ISBN 81-208-1784-2.

- ^ Underwood & Rhodes (2008)

- ^ Chopra 2003, p. 76, citing Sushrutasamhita 25.36.

- Wujastyk 2003, pp. XIX–XX

- ^ Wujastyk 2003, p. XVIII

- Namyata Pathak, A Raut, Ashok Vaidya Acute Cervical Pain Syndrome Resulting from Suppressed Sneezing - JAPI (Accessed on 29 Oct 2013)

- Chopra 2003, p. 75

- Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 11253416, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=11253416instead. - Chopra 2003, p. 79

- ^ Microsoft Corporation (2008). "Ayurveda". Encarta. Redmond, WA: Microsoft. Archived from the original on 28 October 2009.

- Pharmacographia Indica, A history of principal drugs of vegetable origin in British India - Volume 1, William Dymock et al. (1890), London

- ^ Sekar, S. (2007). "Traditional alcoholic beverages from Ayurveda and their role on human health". Indian Journal of Traditional Knowledge. 6 (1): 144–149. Archived from the original on 18 December 2014.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Mani, Dayanandan and Dhawan, Sunita S. (2011). "Scientific basis of therapeutic uses of opium poppy (Papaver somniferum) in Ayurveda". Acta Horticulturae (International Symposium on Papaver) (1036): 175–180. Retrieved 7 December 2014.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/data-and-analysis/bulletin/bulletin_1955-01-01_3_page002.html

- ^ http://www.new1.dli.ernet.in/data1/upload/insa/INSA_1/20005af3_31.pdf

- Wujastyk 2003, p. 20

- Finger, p. 66

- Sharma, A. K. (2003). "Panchkarma Therapy in Ayurvedic Medicine". In Mishra, Lakshmi Chandra (ed.). Scientific Basis for Ayurvedic Therapies. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. p. 43. ISBN 0-8493-1366-X.

- T.S.S. Dikshith (2008). Safe Use of Chemicals: A Practical Guide. CRC Press. p. 16.

- Elizabeth R. Mackenzie, Birgit Rakel (2006). Complementary and Alternative Medicine for Older Adults: A Guide to Holistic Approaches to Healthy Aging. Springer. p. 215. ISBN 9780826138064.

- "ORIGIN AND DEVELOPMENT OF AYURVEDA: (A BRIEF HISTORY)". US National Library of Medicine National Institutes of Health. Anc Sci Life. 1981 Jul-Sep; 1(1): 1–7.

- Frawley, David; Ranade, Subhash (2001). Ayurveda, Nature's Medicine. Lotus Press. p. 11. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- Singh, Rana P. B.; Rana, Pravin S. (2002). Banaras Region: A Spiritual and Cultural Guide. Varanasi, India: Indica Books. p. 31. ISBN 81-86569-24-3.

- Dhanvantari. (2010). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 4 August 2010, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online: http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/160641/Dhanvantari

- Ṭhākara, Vināyaka Jayānanda (1989). Methodology of Research in Ayurveda. Jamnagar, India: Gujarat Ayurved University Press. p. 7.

- K. Mangathayaru. Pharmacognosy: An Indian perspective. Pearson Education India. p. 2.

- Adam Hart-Davis. History: From the Dawn of Civilization to the Present Day. Penguin. p. 53.

- J. N. Roy, Braja Bihārī Kumāra. India and Central Asia: Classical to Contemporary Periods. Concept Publishing Company. p. 103.

- Leonore Loeb Adler, B. Runi Mukherji. Spirit Versus Scalpel: Traditional Healing and Modern Psychotherapy. Greenwood. p. 76.

- Praveen K. Saxena. Development of Plant-Based Medicines: Conservation, Efficacy and Safety. Springer. p. 48.

- Mohammad Ali Jazayery, Werner Winter (1988). Languages and Cultures: Studies in Honor of Edgar C. Polomé. Walter de Gruyter. p. 116.

- Glucklich, Ariel (2008). The Strides of Vishnu: Hindu Culture in Historical Perspective. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. p. 141. ISBN 978-0-19-531405-2.

- Debiprasad Chattopadhyaya (1991). History of Science and Technology in Ancient India: Formation of the theoretical fundamentals of natural science. p. 153.

- K. Mangathayaru. Pharmacognosy: An Indian perspective. Pearson Education. p. 36.

- Anil Kumar Mehta, Naveen K. Gupta, R. N. Sharma (2002). Health & Harmony Through Ayurveda. B. Jain Publishers. p. 41.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - J. Chandy (1965). Indian Journal of Medical Education, Volume 5. p. 185.

- The Indo-Asian Culture, Volume 9. 1960. p. 61.

- Edgar Thorpe, Showick Thorpe. Pearson General Knowledge Manual 2009. Pearson. p. 196.

- K. R. Srikanthamurthy (2005). Biographical History of Indian Medicine: Pictorial. Chaukhambha Orientalia. pp. 33–35.

- Vaidya Bhagwan Dash. Materia Medica of Ayurveda: Based on: Madanapala's Nighantu. B. Jain Publishers. p. 14.

- Lock et al., p. 836

- Wujastyk 2003, p. XXVI

- ^ Lock 2001, p. 607

- Ramachandra S.K. Rao, Encyclopaedia of Indian Medicine: historical perspective, Volume 1, 2005, 94–98.

- Lock 2001, p. 651

- Lock 2001, p. 652

- Lock 2001, pp. 651–652

- Brett, F. H. (1840). A practical essay on some of the principal surgical diseases of India. Calcutta, India: W. Thacker & Company. p. 458. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- "Legal Status of Traditional Medicine and Complementary/Alternative Medicine: A Worldwide Review". World Health Organization (WHO) Source: (accessed: Tuesday June 24, 2014), c.8.5

- ^ Paul I. Dargan; et al. (2008). "Heavy metal poisoning from Ayurvedic traditional medicines: an emerging problem?" (PDF). Int. J. Environment and Health. 2 (3/4). Inderscience Enterprises Ltd.: 463–74. doi:10.1504/IJENVH.2008.020935. Retrieved 5 October 2011.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - The majority of India’s population uses Ayurvedic medicine exclusively or combined with conventional Western medicine, and it is practiced in varying forms in Southeast Asia. "Ayurvedic Medicine: An Introduction". U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, National Institutes of Health National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM). Archived from the original on 25 October 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Wujastyk 2003, p. XXII

- ^ "Ayurvedic medicine". Cancer Research UK. Retrieved August 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - Wujastyk 2003, p. XVI

- "Welcome to Central Council for Research in Ayurveda and Siddha ( India )". Ccras.nic.in. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- "About TKDL". Traditional Knowledge Digital Library. Archived from the original on 4 July 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Know Instances of Patenting on the UES of Medicinal Plants in India". PIB, Ministry of Environment and Forests. 6 May 2010. Archived from the original on 10 May 2010. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Source of Information". Traditional Knowledge Digital Library (Government of India).

- "Introduction to Central Council of Indian Medicine". Central Council of Indian Medicine (CCIM). Archived from the original on 18 December 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Weeklong programme to observe Health Day". The Himalayan Times. The Himalayan Times. 28 October 2013. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

In Nepal, 80 per cent of the population receives Ayurvedic medicine as first aid treatment.

- Alam, Zulfeequar (2008). Herbal Medicines. New Delhi, India: A.P.H. Publishing. p. 122. ISBN 978-81-313-0358-0.

- Guneratne, Arjun (2009). Culture and the Environment in the Himalaya. Routledge contemporary South Asia series, #24. New York: Routledge. pp. 84–85. ISBN 978-0-415-77883-1.

- "Ministry of Indigenous Medicine". Retrieved 2 December 2012.

- "Institute of indigenous Medicine". Iim.cmb.ac.lk. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- "Statistics Report" (PDF). Sri Lanka Institute of Indigenous Medicine. November 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 April 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "About Us". The Ministry Of Indigenous Medicine (Sri Lanka). 14 February 1980. Archived from the original on 8 November 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Arjuna Aluvihare (November 1993). "Rohal Kramaya Lovata Dhayadha Kale Sri Lankikayo". Vidhusara Science Magazine.

- "Resource Mobilization in Sri Lanka's Health Sector" (PDF). Harvard School of Public Health & Health Policy Programme, Institute of Policy Studies. February 1997. p. 19. Retrieved 17 December 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - Müller-Dietz, Heinz E. (1975). "Die Krankenhaus-ruinen in Mihintale (Ceylon)". Historia Hospitalium. 10. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Krankenhausgeschichte: 65–71.

- "From time to time, even the most prestigious science journals publish erroneous or fraudulent data, unjustified conclusions, and sometimes balderdash. Balderdash was the right word when The Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) published the article, "Maharishi Ayur-Veda: Modern Insights Into Ancient Medicine," in its 22/29 May issue. Discovering that they had been deceived by the article's authors, the editors published a correction in the 14 August issue, which was followed on 2 October by a six-page expose on the people who had hoodwinked them." Skolnick, Andrew A. (Fall 1991). "The Maharishi Caper: Or How to Hoodwink Top Medical Journals". National Association of Science Writers. Archived from the original on 16 July 2008.

- Skolnick, A. A. (1991). "Maharishi Ayur-Veda: Guru's marketing scheme promises the world eternal 'perfect health'". JAMA. 266 (13): 1741–2. doi:10.1001/jama.1991.03470130017003. PMID 1817475.

- "National Policy on Traditional Medicine and Regulation of Herbal Medicines" (PDF). World Health Organization. May 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Karta Purkh Singh Khalsa and Michael Tierra: “Independently, we both first learned Ayurvedic medicine from our respective spiritual mentors – myself with Baba Hari Dass and K.P., with Yogi Bhajan.“ (p.X); The way of Ayurvedic Herbs, Lotus Press, 2008, ISBN 978-0-9409-8598-8

- "Ayurvedic Medicine: An Introduction". NCCAM. Retrieved 7 December 2014.

- "Ayurveda". American Cancer Society. American Cancer Society. 26 August 2011. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

The effectiveness of Ayurveda has not been proven in scientific studies, but early research suggests that certain herbs may offer potential therapeutic value

- Mamtani, R.; Mamtani, R. (2005). "Ayurveda and Yoga in Cardiovascular Diseases". Cardiology Review. 13 (3): 155–162. doi:10.1097/01.crd.0000128730.31658.36. PMID 15834238.

- "Research in Ayurveda - About CCRAS". Central Council for Research in Ayurveda and Siddha. Department Of AYUSH, Ministry Of Health and Family Welfare. Archived from the original on 30 May 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "China hands over Ayurveda research centre to govt". Kantipur Publications. The Kathmandu Post. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

The centre will play a positive role in promotion and utilisation of Ayurveda in the country, by conducting research on medicinal herbs available here.

- ^ Valiathan, MS (2006). "Ayurveda: putting the house in order" (pdf). Current Science. 90 (1). Indian Academy of Sciences: 5–6.

- ^ Saper RB; Phillips RS; et al. (2008). "Lead, mercury, and arsenic in US- and Indian-manufactured medicines sold via the internet". JAMA. 300 (8): 915–923. doi:10.1001/jama.300.8.915. PMC 2755247. PMID 18728265.

- Urmila, T.; Supriya, B. (2008). "Pharmacovigilance of ayurvedic medicines in India". Indian Journal of Pharmacology. 40 (S1): 10–12.

- Saper, R. B.; Kales SN; Paquin, J; et al. (2004). "Heavy metal content of ayurveda herbal medicine products". Journal of the American Medical Association. 292 (23): 2868–2673. doi:10.1001/jama.292.23.2868. PMID 15598918.

- ^ Ellin, Abby (17 September 2008). "Skin deep: ancient, but how safe?". New York Times. Archived from the original on 18 September 2008. Retrieved 19 September 2008.

A report in the August 27 issue of The Journal of the American Medical Association found that nearly 21 percent of 193 ayurvedic herbal supplements bought online, produced in both India and the United States, contained lead, mercury or arsenic.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Szabo, Liz (26 August 2008). "Study finds toxins in some herbal medicines". USA Today. Archived from the original on 8 October 2012.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Ayurveda linked to lead poisoning in US women". The Financial Express (Washington edition ed.). 24 August 2012. Archived from the original on 9 December 2014.

{{cite news}}:|edition=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Saper RB; Phillips RS; Sehgal A (August 2008). "Lead, mercury, and arsenic in US- and Indian-manufactured ayurvedic medicines sold via the internet". JAMA. 300 (8): 915–923. doi:10.1001/jama.300.8.915. PMC 2755247. PMID 18728265.

- "Use caution with Ayurvedic products". US FDA. Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- Cited references

- Chopra, Ananda S. (2003). "Āyurveda". In Selin, Helaine (ed.). Medicine across cultures: history and practice of medicine in non-western cultures. Kluwer Academic. pp. 75–83. ISBN 1-4020-1166-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dwivedi, Girish; Dwivedi, Shridhar (2007). "History of Medicine: Sushruta – the Clinician – Teacher par Excellence" (PDF). Indian Journal of Chest Diseases and Allied Sciences. 49. Delhi: Vallabhbhai Patel Chest Institute, University of Delhi / National College of Chest Physicians: 243–244. (Republished by National Informatics Centre, Government of India.)

- Finger, Stanley (2001). Origins of Neuroscience: A History of Explorations into Brain Function. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-514694-8.

- Kutumbian, P. (1999). Ancient Indian Medicine. Andhra Pradesh, India: Orient Longman. ISBN 978-81-250-1521-5.

- Lock, Stephen (2001). The Oxford Illustrated Companion to Medicine. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-262950-6.

- Underwood, E. Ashworth; Rhodes, P. (2008). "History of Medicine". Encyclopædia Britannica (2008 ed.).

- Wujastyk, D. (2003). The Roots of Ayurveda: Selections from Sanskrit Medical Writings. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-044824-1.

Further reading

- William Dymock; et al. (1890). Pharmacographia Indica A history of principal drugs of vegetable origin in British India. Vol. 1. London.

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Thomas T. Wise (1845). Commentary on the Hindu System of Medicine. Calcutta: Thacker & Co.

- Drury, Heber (1873). The Useful plants of India. William H Allen & Co., London. ISBN 1-4460-2372-9.

- Hoernle, Rudolf August Friedrich (1907). Studies in the Medicine of Ancient India: Part I: Osteology. Clarendon Press, Oxford.

- Kishor Patwardhan (2008). Pabitra Kumar Roy (ed.). Concepts of Human Physiology in Ayurveda (PDF). Samyak Vak Series-14. Sarnath, Varanasi: Central Institute of Higher Tibetan Studies. pp. 53–73. ISBN 978-81-87127-76-5.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - WHO guidelines on safety monitoring of herbal medicines in pharmacovigilance systems

- Use caution with ayurvedic products US Food and Drug Administration.

External links

- Template:Dmoz

- Ayurveda: Benchmarks for trainings in traditional/complementary and alternative medicine World Health Organization (WHO)

- National Library of Ayurveda Medicine

| Hinduism | |

|---|---|

| Types of massage | |

|---|---|