| Revision as of 20:15, 22 July 2006 editWBardwin (talk | contribs)Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers20,628 edits restore contrast with other kiln types← Previous edit | Revision as of 20:18, 22 July 2006 edit undoWBardwin (talk | contribs)Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers20,628 edits Distinguish variant sectionNext edit → | ||

| Line 19: | Line 19: | ||

| The length of the firing depends on the volume of the kiln, and may take anywhere from 48 hours to 12 days or more. The kiln generally takes the same amount of time to cool down. Records of historic firings in large Asian kilns shared by several village potters describe several weeks of steady stoking per firing. | The length of the firing depends on the volume of the kiln, and may take anywhere from 48 hours to 12 days or more. The kiln generally takes the same amount of time to cool down. Records of historic firings in large Asian kilns shared by several village potters describe several weeks of steady stoking per firing. | ||

| ==Kiln variants== | |||

| One variant on the anagama style is the '''waritake kiln'''. A waritake kiln is akin to anagama in structure, but it has partition walls built every several meters through the length of the kiln. Each partition can be side stoked. Perhaps the most efficient woodfired kiln design is the '''Noborigama'''. Noborigama are multi-chambered kilns built on a slope with each succeeding chamber situated higher than the one before it (such kilns are often described as "climbing kilns"). The chambers in a noborigama are pierced at intervals with stoking ports, and may be built on a steeper slope so that a better updraft can be achieved. Climbing kilns have been used in Japan since the 17th century. The '''Renboshiki noborigama''' is a multi-chambered climbing kiln. There are many distinguishing characteristics between the noborigama and anagama style. For example, an anagama is somewhat like a half-tube with a fire burned at the lower end. A noborigama is like a set of half-tubes placed side-by-side with piercings that allow each chamber to feed into the next. | |||

| The jagama (snake kiln or dragon kiln) is related to anagama, noborigama, and waritake kilns, and was used extensively in China for thousands of years. Jagama are tube shaped similarly to anagama kilns, but they can be very long -- 200' (60 m) is not unreasonable. Although partitioned and side stoked, jagama do not have partition walls, rather, improvised walls are created by densely stacking pottery at intervals. | The '''jagama''' (snake kiln or dragon kiln) is related to anagama, noborigama, and waritake kilns, and was used extensively in China for thousands of years. Jagama are tube shaped similarly to anagama kilns, but they can be very long -- 200' (60 m) is not unreasonable. Although partitioned and side stoked, jagama do not have partition walls, rather, improvised walls are created by densely stacking pottery at intervals. | ||

| The main advantage these larger multi-chambered kilns have is that exhaust heat created during firing of the lower chambers, preheats the chambers above. Thus, work in the upper chambers requires only the additional fuel needed to bring the work to temperature. The fuel efficiency of this design may have been essential for high temperature ceramics to be economically viable in Asia long (perhaps a thousand years) before the use of coal in Europe. (A modern type, called a ''tube kiln'' improves the efficiency and output still further by having the ware move through the kiln in a direction opposite to that of the hot gasses.) | The main advantage these larger multi-chambered kilns have is that exhaust heat created during firing of the lower chambers, preheats the chambers above. Thus, work in the upper chambers requires only the additional fuel needed to bring the work to temperature. The fuel efficiency of this design may have been essential for high temperature ceramics to be economically viable in Asia long (perhaps a thousand years) before the use of coal in Europe. (A modern type, called a ''tube kiln'' improves the efficiency and output still further by having the ware move through the kiln in a direction opposite to that of the hot gasses.) | ||

Revision as of 20:18, 22 July 2006

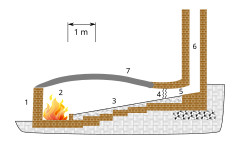

1 Door about 75cm wide

2 Firebox.

3 Stacking floor made of silica sand.

4 Dampers.

5 Flue.

6 Chimney.

7 Refractory arch

The Anagama kiln is an ancient type of pottery kiln brought to Japan from China via Korea in the 5th century.

An anagama (a Japanese term meaning "cave kiln") consists of a firing chamber with a firebox at one end and a flue at the other (note that although the term "firebox" is used to describe the space for the fire, there is no physical structure separating the stoking space from the pottery space). The term Anagama describes single-chamber kilns built in a sloping tunnel shape. In fact, ancient kilns were sometimes built by digging tunnels into banks of clay.

The anagama is fueled with firewood, in contrast to electric or gas-fueled kilns used by most contemporary potters. A large amount of fuel is needed for firing, with stoking occurring round-the-clock until an appropriate temperature is reached. (Wood thrown into the hot kiln is consumed very rapidly.) Stoneware and porcelain pieces will typically mature at "cone 10", a measure of "heat work" dependent on the final temperature coupled with the time required to achieve that temperature (see pyrometric cone). Somewhat inaccurately, cone 10 could be thought of as a temperature range as high as 2375 °F (1300 °C).

Burning wood not only produces heat — up to 2,500 °F (1400 °C) — it also produces fly ash and volatile salts. Wood ash settles on the pieces during the firing, and the complex interaction between flame, ash, and the minerals comprising the clay body forms a natural ash glaze. This glaze may show great variation in color, texture, and thickness, ranging from smooth and glossy to rough and sharp. The placement of pieces within the kiln distinctly affects the pottery's appearance, as pieces closer to the firebox may receive heavy coats of ash, or even be immersed in embers, while others deeper in the kiln may only be softly touched by ash effects. Besides location in the kiln, the way pieces are placed near each other affects the flame path and thus, the appearance of pieces within localized zones of the kiln can vary as well. It is said that loading an anagama kiln is the most difficult part of the firing. The potter must imagine the flame path as it rushes through the kiln, and use this sense to paint the pieces with fire.

The length of the firing depends on the volume of the kiln, and may take anywhere from 48 hours to 12 days or more. The kiln generally takes the same amount of time to cool down. Records of historic firings in large Asian kilns shared by several village potters describe several weeks of steady stoking per firing.

Kiln variants

One variant on the anagama style is the waritake kiln. A waritake kiln is akin to anagama in structure, but it has partition walls built every several meters through the length of the kiln. Each partition can be side stoked. Perhaps the most efficient woodfired kiln design is the Noborigama. Noborigama are multi-chambered kilns built on a slope with each succeeding chamber situated higher than the one before it (such kilns are often described as "climbing kilns"). The chambers in a noborigama are pierced at intervals with stoking ports, and may be built on a steeper slope so that a better updraft can be achieved. Climbing kilns have been used in Japan since the 17th century. The Renboshiki noborigama is a multi-chambered climbing kiln. There are many distinguishing characteristics between the noborigama and anagama style. For example, an anagama is somewhat like a half-tube with a fire burned at the lower end. A noborigama is like a set of half-tubes placed side-by-side with piercings that allow each chamber to feed into the next.

The jagama (snake kiln or dragon kiln) is related to anagama, noborigama, and waritake kilns, and was used extensively in China for thousands of years. Jagama are tube shaped similarly to anagama kilns, but they can be very long -- 200' (60 m) is not unreasonable. Although partitioned and side stoked, jagama do not have partition walls, rather, improvised walls are created by densely stacking pottery at intervals.

The main advantage these larger multi-chambered kilns have is that exhaust heat created during firing of the lower chambers, preheats the chambers above. Thus, work in the upper chambers requires only the additional fuel needed to bring the work to temperature. The fuel efficiency of this design may have been essential for high temperature ceramics to be economically viable in Asia long (perhaps a thousand years) before the use of coal in Europe. (A modern type, called a tube kiln improves the efficiency and output still further by having the ware move through the kiln in a direction opposite to that of the hot gasses.)

References

Furutani, Michio; Anagama: Building Kilns and Firing (2003) (unpublished translation manuscript on file with www.anagama-west.com).

External Links

- Young International Woodfirer Association, an international association of people building and using Anagama kilns and other woodfired kilns

- The Log Book, the magazine about anagamas and woodfiring in general