| Revision as of 21:29, 26 June 2015 view sourceعمرو بن كلثوم (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users4,412 edits →Ethnic cleansing← Previous edit | Revision as of 22:34, 26 June 2015 view source عمرو بن كلثوم (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users4,412 edits →Ottoman Empire: Added more info on 1920 immigrationsNext edit → | ||

| Line 73: | Line 73: | ||

| The demographics of this area saw a huge shift in the early part of the 20th century. Some Kurdish tribes cooperated with ] authorities in the massacres against ] and ] Christians in ],<ref name="R. S. Stafford 2006 25">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.nl/books?id=LSzuzsRh37gC&pg=PA25#v=onepage&q&f=false|title= The Tragedy of the Assyrians|author= R. S. Stafford|page= 25|year= 2006}}</ref> and were in return granted their land as a reward.<ref>Hovannisian, Richard G., 2007. . Accessed on 11 November 2014.</ref> Many Assyrians fled to Syria following the ] committed by the Ottoman Turks and Kurds in Turkey,<ref name="R. S. Stafford 2006 25"/><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.meforum.org/17/syria-and-iraq-repression|title= Ray J. Mouawad, Syria and Iraq – Repression Disappearing Christians of the Middle East|publisher= Middle East Forum|date=2001|accessdate=20 March 2015}}</ref> and settled mainly in the Jazira area.<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.nl/books?id=n4kTdYgwQPkC&pg=PA162#v=onepage&q&f=false|title= Islam and Dhimmitude: Where Civilizations Collide|author= Bat Yeʼor|page= 162|year= 2002}}</ref> | The demographics of this area saw a huge shift in the early part of the 20th century. Some Kurdish tribes cooperated with ] authorities in the massacres against ] and ] Christians in ],<ref name="R. S. Stafford 2006 25">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.nl/books?id=LSzuzsRh37gC&pg=PA25#v=onepage&q&f=false|title= The Tragedy of the Assyrians|author= R. S. Stafford|page= 25|year= 2006}}</ref> and were in return granted their land as a reward.<ref>Hovannisian, Richard G., 2007. . Accessed on 11 November 2014.</ref> Many Assyrians fled to Syria following the ] committed by the Ottoman Turks and Kurds in Turkey,<ref name="R. S. Stafford 2006 25"/><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.meforum.org/17/syria-and-iraq-repression|title= Ray J. Mouawad, Syria and Iraq – Repression Disappearing Christians of the Middle East|publisher= Middle East Forum|date=2001|accessdate=20 March 2015}}</ref> and settled mainly in the Jazira area.<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.nl/books?id=n4kTdYgwQPkC&pg=PA162#v=onepage&q&f=false|title= Islam and Dhimmitude: Where Civilizations Collide|author= Bat Yeʼor|page= 162|year= 2002}}</ref> | ||

| The Assyrian population of Nusaybin crossed the border into Syria and settled in ], which was separated by the railway (new border) from the former. Nusaybin became Kurdish and Qamishli became an Assyrian city.{{citation needed|date=June 2015}} Furthermore, in the 1920s after the failed ] in ], there were waves of Kurdish immigrants fleeing from Turkey into Syria’s Jazira province, where they were granted citizenship by the ].<ref>Chatty, Dawn, 2010. . Cambridge University Press. pp. 230-232.</ref> It is estimated that 25,000 Kurds fled at this time to Syria.<ref name=McDowell>{{cite book|last=McDowell|first=David|title=A modern history of the Kurds|year=2005|publisher=Tauris|location=London |isbn=1850434166|pages=469|edition=3. revised and upd. ed., repr.}}</ref> | |||

| The Assyrian population of Nusaybin crossed the border into Syria and settled in ], which was separated by the railway (new border) from the former. Nusaybin became Kurdish and Qamishli became an Assyrian city.{{citation needed|date=June 2015}} | |||

| === French Mandate === | === French Mandate === | ||

Revision as of 22:34, 26 June 2015

Rojava

| |

|---|---|

Flag

Flag | |

| Anthem: "Ey Reqîb" | |

Map showing de facto cantons held by PYD forces in February 2014 Map showing de facto cantons held by PYD forces in February 2014 | |

| Status | de facto autonomous region of Syria |

| Capital | Qamişlo (Qamishli) |

| Official languages | Kurdish Arabic Syriac-Aramaic |

| Government | Democratic confederalism |

| • Co-President | Asya Abdullah |

| • Co-President | Salih Muslim Muhammad |

| Autonomous region | |

| • Autonomy Proposed | July 2013 |

| • Autonomy Declared | November 2013 |

| • Regional government established | November 2013 |

| • Interim Constitution Adopted | January 2014 |

| Population | |

| • 2014 estimate | 4.6 million |

| Currency | Syrian pound (SYP) |

Rojava or Western Kurdistan (Template:Lang-ku, from rojava meaning "west") is a de facto autonomous region in northern and north-eastern Syria. The region gained its autonomy beginning in November 2013 as part of the Rojava campaign, establishing a society based on principles of direct democracy, gender equity, and sustainability. Rojava consists of the three non-contiguous cantons of (from East to West) Jazira, Kobani and Afrin. Rojava is not officially recognized as autonomous by the government of Syria and is at war with ISIL.

Kurds generally consider Rojava to be one of the four parts of a greater Kurdistan, which also includes parts of southeastern Turkey (Northern Kurdistan), northern Iraq (Southern Kurdistan), and western Iran (Eastern Kurdistan). However Rojavan government and society is polyethnic.

Name

Rojava (Template:Lang-ku, from rojava meaning "west") is also known as Western Kurdistan or Syrian Kurdistan.

Geography

Rojava lies to the west of the River Tigris along the Turkish border. There are three separate cantons: Jazira Canton, Kobani Canton and Afrin Canton. All are at latitude approximately 36 and a half degrees north and are relatively flat. Jazira Canton also borders Iraqi Kurdistan to the south-east. Other borders are disputed in the Syrian Civil War. Kurd Dagh is a mountainous area linked to the rest of Kurdistan and is also inhabited by Kurds. It is the westernmost edge of Kurdistan which stretches to within 20 kilometers of Mediterranean Sea. To the east, the mountainous part of Azaz is also inhabited by Kurds and there is a Kurdish minority living in northern Jarablos and Idlib. Stefan Sperl say that there is a reason to believe that Kurdish settlements in these areas go back to the Seleucid era, since those regions stood in the path to Antioch. Kurds in the early periods served as mercenaries and mounted archers.

History

Further information: Kurdistan, Kurds in Syria, and Modern history of SyriaThe region of Kurd Dagh was already Kurdish-inhabited when the Crusades broke out at end of the 11th century C.E.

Ottoman Empire

See also: Ottoman Syria

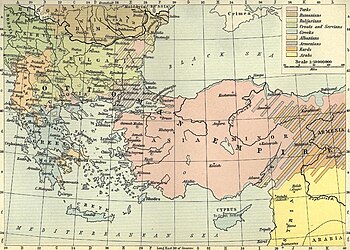

During the Ottoman period (1299–1922), large Kurmanji-speaking Kurdish tribal groups both settled in and were deported to areas of northern Syria from Anatolia. The largest of these tribal groups was the Reshwan confederation, which was initially based in the Adiyaman region but eventually also settled throughout Anatolia. The Milli confederation, which was documented in Ottoman

sources from the year 1518 onward, was the most powerful tribal group and dominated the entire northern Syrian steppe in the second half of the 18th century. Their influence continued to rise and eventually their leader Timur was appointed Ottoman governor of Raqqa (1800-1803). Kurdish dynasty of Janbulads ruled the region of Aleppo as governors for the Ottomans from 1591 to 1607 and were allied with the Medici of Tuscany.

The Danish writer Carsten Niebuhr who traveled to Jazira in 1764 recorded five nomadic Kurdish tribes (Dukurie, Kikie, Schechchanie, Mullie and Aschetie) and one Arab tribe. According to Niebuhr, those tribes were settled near Mardin in Turkey, and paid the governor of that city for the right of grazing their herds in the Syrian Jazira. These Kurdish tribes gradually settled in villages and cities and are still present in Jazira (modern Syria's Hasakah Governorate).

Until the 19th century, Kurdistan did not include lands of Syrian Jazira. Similarly, Kurdistan as suggested by the Treaty of Sèvres did not include any territory in what later became Syria and Iraq.

The demographics of this area saw a huge shift in the early part of the 20th century. Some Kurdish tribes cooperated with Ottoman authorities in the massacres against Armenian and Assyrian Christians in Upper Mesopotamia, and were in return granted their land as a reward. Many Assyrians fled to Syria following the Assyrian genocide committed by the Ottoman Turks and Kurds in Turkey, and settled mainly in the Jazira area.

The Assyrian population of Nusaybin crossed the border into Syria and settled in Qamishli, which was separated by the railway (new border) from the former. Nusaybin became Kurdish and Qamishli became an Assyrian city. Furthermore, in the 1920s after the failed Kurdish rebellions in Kemalist Turkey, there were waves of Kurdish immigrants fleeing from Turkey into Syria’s Jazira province, where they were granted citizenship by the French mandate authorities. It is estimated that 25,000 Kurds fled at this time to Syria.

French Mandate

Things soon changed, however, with the immigration of Kurds beginning in 1926 following the failure of the rebellion of Saeed Ali Naqshbandi against the Turkish authorities. While many of the Kurds in Syria have been there for centuries, waves of Kurds fled their homes in Turkey and settled in Syria, where they were granted citizenship by the French mandate authorities. This large influx of Kurds moved to Syria’s Jazira province. It is estimated that 25,000 Kurds fled at this time to Syria.

Assyrians began to emigrate from Syria after the Amuda massacre of August 9, 1937. This massacre, carried out by the Kurd Saeed Agha al-Dakuuri, emptied the city of its Assyrian population. In 1941, the Assyrian community of al-Malikiyah was subjected to a vicious assault. Even though the assault failed, Assyrians were terrorized and left in large numbers, and the immigration of Kurds from Turkey to the area converted al-Malikiya, al-Darbasiyah and Amuda to completely Kurdish cities.

Pre-autonomy government from Damascus

Rojava under Syrian rule had little investment or development from the central government. Laws discriminated against Kurds from owning property, and many were without citizenship. Property was routinely confiscated by government loansharks. There were no high schools, and Kurdish language education in middle schools was forbidden, compromising Kurdish students' education. Hospitals lacked equipment for advanced treatment and instead patients had to be transferred outside Rojava.

Arabization policy of Syrian governments

Successive Syrian governments continued to adopt a policy of ethnic discrimination and national persecution against Kurds, completely depriving them of their national, democratic and human rights. Syrian governments imposed ethnically-based programs, regulations and exclusionary measures on various aspects of Kurds’ lives – political, economic, social and cultural – among which are the following:

- On 1962 the Syrian authorities in Hasaka randomly stripped tens of thousands of Kurdish families (more than 120,000 Kurds) of their Syrian nationality. A census was implemented exclusively in Hasaka province for a period of just 24 hours only, and as a result tens of thousands of Syrian citizens of Kurdish origins lost their nationality and found themselves deprived of their citizenship. The census prevented all those affected by it from exercising all the natural rights that are based on citizenship – civil, social, political, cultural and economic – fro exercising their right to work, to employment, to education, travel, the right to own a property and use agricultural land and from living normal lives.

- In 1973 in the province of Hasaka, the Syrian authorities confiscated an area of fertile agricultural land owned and cultivated by tens of thousands of Kurdish citizens and gave it to Arab families brought in from the provinces of Aleppo and Ar-Raqqa. The National Leadership Bureau of the ruling Baath Party issued orders to establish 41 settlement centers in these areas, in order to change the demographic composition of these areas by evicting and displacing the Kurdish inhabitants. On 2007, Syrian authorities in the Agricultural Association in Malikiyah, Hasaka province, signed contracts granting 150 Arab families from the Shaddadi region, Hasaka province, about six thousand square kilometers in Malikiyah. At the same time, it evicted tens of thousands of Kurdish people from these villages, and forcing them to move to other areas inside and outside of Syria in search of a decent living.

- In 1967, all references to Kurds in Syria were removed from geography curriculum books, and many Kurdish citizens were subject to pressure from the staff of the Civil Registry Departments to not give their children Kurdish names.

- On 1986, the governor of Hasaka issued a Resolution which prohibits the use of the Kurdish language in the workplace. In 1989, the governor of Hasaka, Mohammed Mustafa Miro, issued another resolution to re-confirm this ban on speaking Kurdish and added to it a prohibition on non-Arabic songs at weddings and holidays.

- In the 1960s, Syrian authorities planned to change the original Kurdish names of scores of villages in Hasakeh governorate in the northeast and in the Kurdish area in Kurd Dagh, in the northwest near Afrin in the governorate of Aleppo, and began to implement it in the 1970s. In Afrin the place names of all Kurdish villages have been changed to Arabic. Some of the names which had been changed to Arabic are: Kobaniya (now Ain al-Arab), Girdeem (Sa`diyya), Chilara (Jowadiyya), Derunakoling (Deir Ayoub), and BaniQasri (Ain Khadra).

Syrian Civil War

Main article: Syrian Kurdistan campaign (2012–present)

Controlled by SAA Remnants Controlled by Syrian Interim Government (SNA) and Turkish Armed Forces Controlled by Syrian Salvation Government (HTS) Controlled by Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (SDF) Controlled by Revolutionary Commando Army and United States Armed Forces Controlled by the Islamic State (IS)

(For a more detailed, interactive map, see Template:Syrian Civil War detailed map.)

In the course of the Syrian Civil War, Syrian government forces withdrew from three Kurdish enclaves leaving control to local militias in 2012. During the Syrian civil war People's Protection Units (YPG) were created by the Kurdish Supreme Committee to control the Kurdish inhabited areas in Syria. In July 2012 the YPG established control in the towns of Kobane, Amuda and Afrin. The two main Kurdish groups, the Kurdish National Council (KNC) and the Democratic Union Party (PYD), afterwards formed a joint leadership council to administer the towns. Later that month the cities of Al-Malikiyah (Dêrika Hemko), Ra's al-'Ayn (Serê Kaniyê), Al-Darbasiyah(Dirbêsî), and Al-Maabadah (Girkê Legê) also came under the control of the Popular Protection Units.

The only major Kurdish inhabited cities that remained under government control were Hasaka and Qamishli. However, parts of Hasaka and Qamishli later also became controlled by the YPG.

In July 2013 ISIS began to forcibly displace Kurdish civilians from towns in Ar-Raqqah governorate. After demanding that all Kurds leave Tel Abyad on or else be killed, thousands of civilians, including Turkmen and Arab families fled on 21 July. Its fighters systematically looted and destroyed the property of Kurds, and in some cases, resettled displaced Arab Sunni families from the Qalamoun area (Rif Damascus), Dayr Az-Zawr and Ar-Raqqah in abandoned Kurdish homes. A similar pattern was documented in Tel Arab and Tal Hassel in July 2013. As ISIS consolidated its authority in Ar-Raqqah, Kurdish civilians were forcibly displaced from Tel Akhader and Kobane (Aleppo) in March and September 2014, respectively.

In 2014 Kobane was besieged by ISIL and later liberated by Euphrates Volcano jpnt Free Syrian Army and YPG forces assisted by coalition airstrikes.

In January 2015 the YPG fought against Syrian regime forces in Hassakeh, again clashing in June 2015 with the Assad regime forces stationed in Qamishli. After the latter clashes, Nasir Haj Mansour, a Kurdish official in the northeast stated “The regime will with time get weaker ... I do not imagine the regime will be able to strengthen its position”.

Government

The Kurdish Supreme Committee (Desteya Bilind a Kurd, DBK) was established by the Democratic Union Party (PYD) and the Kurdish National Council (KNC) as the governing body of Rojava in July 2012. The member board consists of an equal number of PYD and KNC members. In November 2013, the PYD announced an interim government divided into three non-contiguous autonomous areas or cantons, Afrin, Jazira and Kobani.

The political system of Rojava is inspired by Democratic Confederalism and Communalism. It is influenced by anarchist and libertarian principles. The Constitution of Rojava has protection for currency, property rights and free trade. The basic unit at the local level is the community which pools resources for education, protection and governance. At a national level communities are unrestricted in deciding their own economic decisions on who they wish to sell to and how resources are allocated. There is a broad push for social reform, gender equality and ecological stabilization in the region.

Political writer David Romano describes it as pursuing 'a bottom-up, Athenian-style direct form of democratic governance'. He contrasts the local communities taking on responsibility vs the strong central governments favoured by many states. In this model, states become less relevant and people govern through councils similar to the early US or Switzerland before becoming a federal state in the Sonderbund war. Rojava divides itself into regional administrations called cantons named after the Swiss cantons.

Moving towards democratic autonomy

The governance model of Rojava has an emphasis on local management with regions divided into cantons with committees to democratically make decisions. The Movement for a Democratic Society (also known as TEV-DEM) is the political coalition governing the democratically autonomous Kurdish areas of northern Syria referred to collectively as Rojava.

Its programme immediately aimed to be "very inclusive" and people from a range of different backgrounds became involved (including Kurds, Arabs, Assyrians, and Turkmen (from Muslim, Christian, and Yazidi religious groups). It sought to "establish a variety of groups, committees and communes on the streets in neighborhoods, villages, counties and small and big towns everywhere". The purpose of these groups was to meet "every week to talk about the problems people face where they live". The representatives of the different community groups meet "in the main group in the villages or towns called the "House of the People"".

According to Zaher Baher of the Haringey Solidarity Group, the TEV-DEM has been "the most successful organ" in Rojava because it has the "determination and power" to change things, it includes many people who "believe in working voluntarily at all levels of service to make the event/experiment successful", and it has "set up an army of defence consisting of three different parts" - the YPG, the YPJ, the Asaish, a "mixed force of men and women that exists in the towns and all the checkpoints outside the towns to protect civilians from any external threat", and "a special unit for women only, to deal with issues of rape and domestic violence".

Centralised political representation

Alongside TEV-DEM there is the Democratic Society Movement, an interim governing body of Rojava and consists of an equal number of Kurdish Democratic Union Party (PYD) and Kurdish National Council (KNC) members. This council mainly is concerned with external affairs.

Political parties include: Democratic Union Party (Syria), Syriac Union Party (Syria), Kurdish National Council

There are no plans for independence from Syria, but for self-administration and control of local resources.

Kurdish officials said they planned to hold elections for a new government before the end of 2014, but this was postponed due to fighting. However some local elections were held in March 2015.

There are 20 ministries dealing with the economy, agriculture, natural resources, and foreign affairs. Among other stipulations outlined is a quota of 40% for women’s participation in government, as well as another quota for youth. Separately in connection with a decision to introduce affirmative action for minority ethnicities, all governmental organizations and offices are based on a co-presidential system.

Human rights violations

Hundreds of different human rights violations have been recorded by PYD and other Kurdish military and police militias in all areas under their control. The violations include forcible recruitment, kidnappings, assassinations, executions, torture, ethnic cleansing, expulsion, intimidation of other Kurdish parties, destruction of properties, and burning houses of Arab villagers in Qamishli area.

Legally women have equal rights and there are quotas for their political representation. There is affirmative action to give power to minority groups and ethnicities as a guiding principle.

Human Rights Watch was permitted to visit in early 2014, reported "arbitrary arrests, due process violations, and failed to address unsolved killings and disappearances" and made recommendations for government improvement. However, Fred Abrahams, special advisor to HRW who visited Rojava and drafted the report, noted that the PYD has taken solid steps to addressing the problems and has been receptive to criticism. He notes that they are currently in the process of political transitioning from the Syrian government, training a new police force and creating a new legal system.

There has also been allegations of teenage fighters serving in the YPG military. After criticism from Human Rights Watch when the problem persisted, the YPG pledged publically to demobilize all fighters under 18 within a month. It is worth noting that the YPG is a "decentralised army", and individual units act autonomously. However the YPG has taken steps to prevent teenage volunteer fighters under the age of 18.

Torture is a common practice of PYD militias against opponents and those who refuse forcible recruitment.

Ethnic cleansing

The YPG have been accused of ethnic cleansing against Arabs and Turkmen; which led to the fleeing of thousands and the destruction of several Arab villages — a charge strongly denied by the Kurds. The accusation was not backed by any evidence of ethnic or sectarian killings. The head of Syrian Observatory for Human Rights said the people who had fled into Turkey were escaping fighting and there was no systematic effort to force people out. Previous reports by Kurdish human rights organization KurdWatch have talked about similar ethnic cleansing operations in villages around the Jabal ʿAbdulʿaziz area in al-Hasakah Governorate, and burning houses of Arab villagers in Qamishli area.

Forcible fighter recruitment

According to Kurdish human rights organization KurdWatch, several incidents of forcible recruitment, including 16-year-old boys, have happened in by PYD forces. The latest of these events happened in Afrin District during which approximately two hundred young men were forcibly recruited. In a previous incident on 12 June 2015, christian men in Qamishli resisted forcible a kidnapping attempt for recruitment in PYD militia. The situation escalated further with the arrival of vehicles of the regime-affiliated Christian Sootoro militia and one YPG fighter was reportedly seriously injured. In another incident, a 14-year-old girl was forcibly recruited. Local Kurdish residents in Amuda had rallied against forcible recruitment of minors.

Oppression against other political parties

Several incidents involved assassination, violence, torture, or expulsion of political opponents of PYD militias. In one incident, the Asayiş, the security service of the Democratic Union Party (PYD), expulsed two Yekîtî (rival Kurdish party) members from their homes in Rumaylan.

Economy

70% of government expenditure is on defense and security.

Private property and entrepreneurship are protected, though accountable to the democratic will of locally organized councils. Dr Dara Kurdaxi, a Rojavan economist, has said that: ‘The method in Rojava is not so much against private property, but rather has the goal of putting private property in the service of all the peoples who live in Rojava.’

The private sector is comparatively small, with the focus being on expanding social ownership of production and management of resources through communes and collectives. Several hundred instances of collectivization have occurred across all towns and villages across the three cantons, with each commune consisting of approximately 20-35 people.

There are also no taxes on the people or businesses in Rojava. Instead money is raised through border crossings, and selling oil or other natural resources. The administration of Rojava is encouraging local community-based cooperatives as a way for people to serve their own needs and provide employment.

Price controls are managed by democratic committees per canton, which can set the price of basic goods such as for food and medical goods. This mechanism can also be used for managing public production to for instance, produce more wheat to keep prices low for important goods.

The government is seeking outside investment to build a power plant and a fertilizer factory.

Resources

Oil and food production exceeds demand so exports include oil and agricultural products such as sheep, grain and cotton. Imports include consumer goods and auto parts. The border crossing of Yaroubiyah is intermittently closed by the Iraqi side. Turkey does not allow Syrian Kurd business people or their goods to cross the border although Rojava would like the border to be opened.

Before the war, Al-Hasakah governorate was producing about 40,000 barrels of crude oil a day. However, during the war the oil refinery has been only working at 5% capacity due to lack of refining chemicals, some people work at polluting and primitive oil refining.

In 2014, the Syrian government was still paying some state employees, but fewer than before however the government says that "none of our projects are financed by the regime".

Military and police

The DBK's armed wing is the People's Protection Units (Yekîneyên Parastina Gel, YPG). Military service was declared compulsory in July 2014 due to the ongoing war against Daesh.

The People's Protection Units was founded by the PYD party after the 2004 Qamishli clashes, but it was not active until the Syrian Civil War. As of the signing of the Arbil Agreement by PYD and KNC the Armed Wing came under the command of the Kurdish Supreme Committee, though in reality it is almost exclusively still the armed wing of the PYD. The Sutoro is a Christian militia defending Assyrian areas. The police function in Rojava-controlled areas is performed by the Asayish armed formation.

The YPG is a trained force utilising snipers and mobile weaponry to launch hit and run attacks and maneuvre quickly.

Relying on speed, stealth, and surprise, it is the archetypal guerrilla army, able to deploy quickly to front lines and concentrate its forces before quickly redirecting the axis of its attack to outflank and ambush its enemy. The key to its success is autonomy. Although operating under an overarching tactical rubric, YPG brigades are inculcated with a high degree of freedom and can adapt to the changing battlefield.

However resupply is difficult.

The existing police force is trained in non-violent conflict resolution as well as feminist theory before being allowed access to a weapon. Directors of the Asayiş police academy have claimed that the long term goal is to give all citizens six weeks of police training before ultimately eliminating the police.

Demographics

Further information: Kurds in Syria and Demographics of SyriaEthnicity

Most of the people in Rojava are Kurdish. Especially in Jazira Canton there are settlements of Arab people. Most of the people in Khanik and Al-Malikiyah in Jazira Canton are Assyrian. There are also Yezidis, Armenians, and Turkmen.

Religion

Most people are Muslim but some are Christian.There are also other minorities like Zoroastrianism and Yazidis, but a lot of kurdish people in Rojava defend laicism. Interfaith relations are good.

Languages spoken

Kurdish, Arabic and Syriac-Aramaic are spoken.

Population centres

Qamishli is the largest city in jazira canton. Kobane and Efrin are the principal cities of the other cantons.

Foreign relations

Main article: Foreign relations of RojavaTurkey claims the YPG is the same as the PKK, which they consider a terrorist organisation, whereas YPG leaders insist the PKK is a separate organization. In 2014 Turkey was accused of supporting ISIS attacks on the YPG, allowing them to conduct attacks from the Turkish border and providing logistical support.

There is military cooperation with Iraqi Kurdistan and the USA although there is no official support for Rojava or the YPG.

In January 2015, a UK parliament committee asked the government to explain and justify its policy of not working with the Rojava military to combat ISIS.

France is supportive.

See also

Notes

- Modern Curdistan is of much greater extent than the ancient Assyria, and is composed of two parts the Upper and Lower: In the former is the province of Ardelan, the ancient Arropachatis, now nominally a part of Irak Ajami, and belonging to the north west division called Al Jobal. It contains five others, namely, Betlis, the ancient Carduchia, lying to the south and south west of the lake Van. East and south east of Betlis is the principality of Julamerick, south west of it is the principality of Amadia. the fourth is Jeezera ul Omar, a city on an island in the Tigris, which corresponds to the ancient city of Bezabde. The fifth and largest is Kara Djiolan, with a capital of the same name. The pashalics of Kirkook and Solimania also comprise part of Upper Kurdistan. Lower Kurdistan comprises all the level tract to the east of the Tigris, and the minor ranges immediately bounding the plains and reaching thence to the foot of the great range, which may justly be denominated the Alps of western Asia.

A Dictionary of Scripture Geography 1846, John Miles. - This and other aspects of the Rojava revolution have led some anti-capitalists to criticise the revolution for not going far enough e.g. 'Anarchist Federation statement on the Rojava revolution'; Gilles Dauve, 'Rojava: reality and rhetoric'; Alex de Jong, 'Stalinist caterpillar into libertarian butterfly? - the evolving ideology of the PKK'; Anti War, '‘I have seen the future and it works.’ – Critical questions for supporters of the Rojava revolution' and Devrim Valerian, 'The bloodbath in Syria: class war or ethnic war?'. Other anti-capitalists have been significantly less critical e.g. David Graeber, 'No. This is a Genuine Revolution'; Janet Biehl, 'Poor in means but rich in spirit' and the Kurdistan Anarchist Forum

References

- http://basnews.com/en/News/Details/Syrian-Defense-Minister-in-Qamishli--We-won-t-let-anyone-take-Hasakah/21882

- "ISIS suicide attacks target Syrian Kurdish capital - Al-Monitor: the Pulse of the Middle East". Al-Monitor. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- "West Kurdistan divided into three cantons". ANF. 6 January 2014. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- Jongerden, Joost. "Rethinking Politics and Democracy in the Middle East" (PDF). Retrieved 8 September 2013.

- Ocalan, Abdullah (2011). Democratic Confederalism (PDF). ISBN 978-0-9567514-2-3. Retrieved 8 September 2013.

- Ocalan, Abdullah (2 April 2005). "The declaration of Democratic Confederalism". KurdishMedia.com. Retrieved 8 September 2013.

- "Bookchin devrimci mücadelemizde yaşayacaktır". Savaş Karşıtları (in Turkish). 26 August 2006. Retrieved 8 September 2013.

- Wood, Graeme (26 October 2007). "Among the Kurds". The Atlantic. Retrieved 8 September 2013.

- Estimate as of mid November 2014, including numerous refugees. "Rojava’s population has nearly doubled to about 4.6 million. The newcomers are Sunni and Shia Syrian Arabs who have fled the scorched wasteland that Assad has made of his country. They are also Orthodox Assyrian Christians, Chaldean Catholics, and others, from out of the jihadist dystopia that has taken up so much of the space where Assad’s police state used to be." "In Iraq and Syria, it's too little, too late". Ottawa Citizen. 14 November 2014.

- "Barzanî xêra rojavayê Kurdistanê dixwaze". Avesta Kurd (in Kurdish). 15 July 2012. Retrieved 13 May 2015.

- "Yekîneya Antî Teror a Rojavayê Kurdistanê hate avakirin". Ajansa Nûçeyan a Hawar (in Kurdish). 7 April 2015. Retrieved 13 May 2015.

- The secret garden of the Syrian Kurdistan

- "The Constitution of the Rojava Cantons". Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- "Fight For Kobane May Have Created A New Alliance In Syria: Kurds And The Assad Regime". International Business Times. 8 October 2014. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- http://aranews.net/2015/02/kurds-regain-15km-kobane-countryside-killing-dozens-militants/.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Kurdish Awakening: Nation Building in a Fragmented Homeland, (2014), by Ofra Bengio, University of Texas Press

- "A Small Key Can Open A Large Door". Combustion Books. Retrieved 23 May 2015.

- ^ Kreyenbroek, P.G.; Sperl, S. (1992). The Kurds: A Contemporary Overview. Routledge. p. 116. ISBN 0415072654. Cite error: The named reference "sperl" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- Tejel, Jordi (2008). Syria's Kurds: history, politics and society (1. publ. ed.). London: Routledge. p. 9. ISBN 0415424402.

- Winter, Stefan (2009). "Les Kurdes de Syrie dans les archives ottomanes (XVIIIe siècle)". Études Kurdes. 10: 125–156.

- Salibi, Kamal S. (1990). A House of Many Mansions: The History of Lebanon Reconsidered. University of California Press. p. 154. ISBN 9780520071964.

- Carsten Niebuhr (1778). Reisebeschreibung nach Arabien und andern umliegenden Ländern. (Mit Kupferstichen u. Karten.) - Kopenhagen, Möller 1774-1837 (in German). p. 389.

- Stefan Sperl, Philip G. Kreyenbroek (1992). The Kurds a Contemporary Overview. London: Routledge. pp. 145–146. ISBN 0-203-99341-1.

- ^ A Dictionary of Scripture Geography, p 57, by John Miles, 486 pages, Published 1846, Original from Harvard University

- David McDowall (2004). A Modern History of the Kurds: Third Edition. p. 137.

- ^ R. S. Stafford (2006). The Tragedy of the Assyrians. p. 25.

- Hovannisian, Richard G., 2007. . Accessed on 11 November 2014.

- "Ray J. Mouawad, Syria and Iraq – Repression Disappearing Christians of the Middle East". Middle East Forum. 2001. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- Bat Yeʼor (2002). Islam and Dhimmitude: Where Civilizations Collide. p. 162.

- Chatty, Dawn, 2010. Displacement and Dispossession in the Modern Middle East. Cambridge University Press. pp. 230-232.

- ^ McDowell, David (2005). A modern history of the Kurds (3. revised and upd. ed., repr. ed.). London : Tauris. p. 469. ISBN 1850434166.

- Abu Fakhr, Saqr, 2013. As-Safir daily Newspaper, Beirut. in Arabic Christian Decline in the Middle East: A Historical View

- Chatty, Dawn, 2010. Displacement and Dispossession in the Modern Middle East. Cambridge University Press. pp. 230-232.

- Bat Yeʼor (2002). Islam and Dhimmitude: Where Civilizations Collide. p. 159.

- Jordi Tejel (2008). Syria's Kurds: History, Politics and Society. p. 147.

- Keith David Watenpaugh (2014). Being Modern in the Middle East: Revolution, Nationalism, Colonialism, and the Arab Middle Class. p. 270.

- "Efrîn Economy Minister: Rojava Challenging Norms Of Class, Gender And Power".

- ^ "Persecution and Discrimination against Kurdish Citizens in Syria" (PDF). Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights.

- ^ "SYRIA: The Silenced Kurds; Vol. 8, No. 4(E)". Human Rights Watch.

- "A murder stirs Kurds in Syria". The Christian Science Monitor.

- ^ "More Kurdish Cities Liberated As Syrian Army Withdraws from Area". Rudaw. 20 July 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- "Armed Kurds Surround Syrian Security Forces in Qamishli". Rudaw. 22 July 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- "Girke Lege Becomes Sixth Kurdish City Liberated in Syria". Rudaw. 24 July 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- "Report of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic: Twenty-seventh session". UN Human Rights Council.

- "Kurds battle Assad's forces in Syria, opening new front in civil war". Reuters. 17 January 2015. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- Kurds take on Syria regime in Qamishli

- Perry, Tom (17 June 2015). "Syria Kurds seek bigger role after victories". TDS. Reuters. Retrieved 17 June 2015.

The Kurds' alliance with Washington has fueled suspicions in Damascus of a conspiracy to break up Syria, while the Kurds are irritated by what they see as government attempts to recover lost influence in the region

- "Kurdish Supreme Committee in Syria Holds First Meeting". Rudaw. 27 July 2012. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- ^ "Now Kurds are in charge of their fate: Syrian Kurdish official". Rudaw. 29 July 2012. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- "PYD Announces Surprise Interim Government in Syria's Kurdish Regions". Rudaw.

- ^ "Charter of the social contract in Rojava (Syria)".

- "ROJAVA: POLITICAL STRUCTURE OBSCURED BY HEADLINES".

- "A Very Different Ideology in the Middle East".

- "The experiment of West Kurdistan (Syrian Kurdistan) has proved that people can make changes". Anarkismo.net. Retrieved 21 October 2014.

- "War with Isis: The forgotten, plucky Kurds under siege in their enclave on Syria's border with Turkey". Independent. 13 November 2014.

- ^ "Striking out on their own". The Economist.

- "Western Kurdistan's Governmental Model Comes Together". The Rojava Report. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- "Daily Reports on Violations of Human Rights in Syria: 12/03/2015". Syrian Human Rights Committee. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- "US Expresses Concerns About PYD Human Rights". BasNews. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- "KurdWatch reports human rights violations against Kurds in Syria". KurdWatch. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- "Syrian Kurds give women equal rights, snubbing jihadists". Yahoo.

- ^ "Syria: Abuses in Kurdish-run Enclaves". Human Rights Watch. 2014-06-18.

- "Rights Official Speaks of Situation in Rojava, PYD Challenges".

- ^ "Analysis: YPG - the Islamic State's worst enemy".

- "ʿAfrin: PYD kidnaps and tortures teenager and demands that she leave the country". KurdWatch. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- "New interview: Nurman Ibrahim Khalifah, Student: They told her: "This PKK bullet is too good for you!" and shot her in the head". KurdWatch. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- "Thousands of Arabs driven out by Kurds' ethnic cleansing". The Times. 2015. Retrieved 1 June 2014.

- "Kurdish Fighters Seize Large Parts of IS Border Stronghold". The New York Times.

- "Kurdish Fighters Seize Large Parts of IS Border Stronghold". The New York Times.

- "Syrian Kurds battle Islamic State for town at Turkish border". Reuters.

- "Al-Hasakah: YPG expels Arab village residents". KurdWatch. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- "Qamishli: YPG captures IS‑strongholds in al‑Hasakah". KurdWatch. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- "ʿAfrin: Mass forcible recruitment now also taking place in ʿAfrin". KurdWatch. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- "Al-Qamishli: Christians resist forcible recruitment". KurdWatch. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- "Al-Qamishli: PYD recruits fourteen-year-old against her parents' will". KurdWatch. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- "Demonstration against forcible recruitment of minors". KurdWatch. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- "Rumaylan: Asayiş demands that Yekîtî politicians leave their homes". KurdWatch. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- ^ "Poor in means but rich in spirit". Ecology or Catastrophe. Retrieved 21 February 2015.

- Michael Knapp, 'Rojava – the formation of an economic alternative: Private property in the service of all'.

- http://sange.fi/kvsolidaarisuustyo/wp-content/uploads/Dr.-Ahmad-Yousef-Social-economy-in-Rojava.pdf

- "Poor in means but rich in spirit". Ecology or Catastrophe. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ^ "Efrîn Economy Minister Yousef: Rojava challenging norms of class, gender and power". Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- "Kurds Fight Islamic State to Claim a Piece of Syria". The Wall Street Journal.

- "Syrian Kurds risk their lives crossing into Turkey". Middle East Eye. 2014-12-29. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- ^ "Efrîn Economy Minister: Rojava Challenging Norms Of Class, Gender And Power". 2014-12-22.

- "Control of Syrian Oil Fuels War Between Kurds and Islamic State". The Wall Street Journal. 23 November 2014.

- "Flight of Icarus? The PYD's Precarious Rise in Syria" (PDF). International Crisis Group.

- "Zamana LWSL".

- "YPG's Mandatory Military Service Rattles Kurds". 27 August 2014.

- Gold, Danny (31 October 2010). "Meet the YPG, the Kurdish Militia That Doesn't Want Help from Anyone". Vice. Retrieved 9 October 2014.

- van Wilgenburg, Wladimir (5 April 2013). "Conflict Intensifies in Syria's Kurdish Area". Syria Pulse. Al Monitor. Retrieved 9 October 2014.

- "Volunteering with the Kurds to fight IS". BBC.

- https://zcomm.org/znetarticle/no-this-is-a-genuine-revolution/

- "Could Christianity be driven from Middle East?". BBC. 15 April 2015. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- "Meet America's newest allies: Syria's Kurdish minority". CNN.

- "Research Paper: ISIS-Turkey List". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- "Build Kurdistan relationship or risk losing vital Middle East partner".

- http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2015/02/turkey-france-kurdish-guerillas-elysee.html#.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)

External links

- The Constitution of the Rojava Cantons

- BBC documentary: Rojava: Syria's Secret Revolution

- Resources on the Rojava revolution in West Kurdistan (Syria)

- 'Rojava Revolution' Reading Guide

- Prof. Harvey: Rojava must be defended. ANF News, April 14, 2015.

- Discussion about Rojava on Reddit

| Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria articles | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Politics | |||

| Economy | |||

| Culture | |||