| Revision as of 16:36, 1 August 2006 edit136.182.2.221 (talk)No edit summary← Previous edit | Revision as of 16:41, 1 August 2006 edit undoA Musing (talk | contribs)4,975 editsm rv vandalismNext edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| :''For the American journal, see ].'' | |||

| ].]] | ].]] | ||

| Line 240: | Line 241: | ||

| '''Poetry organizations and publications''' | '''Poetry organizations and publications''' | ||

| * | |||

| * | * | ||

| * | * | ||

Revision as of 16:41, 1 August 2006

- For the American journal, see Poetry (magazine).

Poetry (gr. ποίησις, poezis) is a form of art in which language is used for its aesthetic qualities in addition or instead of its ostensible meaning. Poetry has a long history, and early attempts to define poetry, such as Aristotle's Poetics, focused on the various uses of speech in rhetoric, drama, song and comedy. Later attempts focused on the deliberate use of features such as repetition and rhyme and the emphasis on aesthetics to distinguish poetry from prose. Now a days contemporary poets, such as Dylan Thomas, often identify poetry not as a literary genre within a set of genres, but as a fundamental creative act using language.

Poetry often uses condensed forms and conventions to reinforce or expand the meaning of the underlying words or to invoke emotional or sensual experiences in the reader, as well as using devices such as assonance, alliteration and rhythm to achieve musical or incantatory effects. Poetry's use of ambiguity, symbolism, irony and other stylistic elements of poetic diction often leaves a poem open to multiple interpretations.

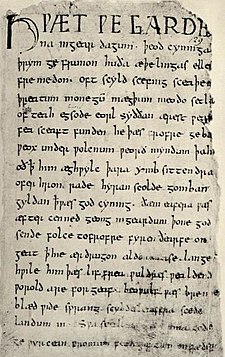

Specific forms of poetry have become traditional within and across different cultures and genres, and often respond to underlying characteristics of the language in which poetry is created. Each language's richness in rhyme and method of creating timing and tonal differences provides distinct opportunities for poets writing in that language. While those accustomed to identifying poetry with Shakespeare, Dante and Goethe may understand poetry by reference primarily to rhyming lines and regular accentual meter, other traditions, such as those of Du Fu and Beowulf, use other methods to achieve rhythm and euphony. In today's globalized world, poets often borrow styles, techniques and forms by different cultures and languages.

Poetics and history

Main articles: History of poetry and Literary theory

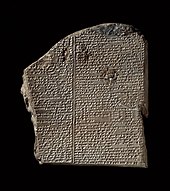

The history of poetry as an art form may predate literacy, and early oral poetry may have used rhyme, rhythm, and other formal systems as mnemonic devices. Many ancient works, from the Vedas (2500 - 500 BC) to the Odyssey (600 - 500 BC), appear to have been composed as poetry to aid memorization and assist in oral transmission in prehistoric and ancient societies. Poetry appears among the earliest records of most literate cultures, with poetic fragments found on early monoliths such as rune stones and stelae. Among the oldest surviving poems are those of Gilgamesh, from the third millennia BC in Sumer, which were written in cuneiform script on clay tablets and, later, papyrus.

Ancient thinkers sought to determine what makes poetry distinctive as a form and what distinguishes good poetry from bad, resulting in the development of "poetics", or the study of the aesthetics of poetry. Some ancient societies, such as the Chinese through the Shi Jing, one of the Five Classics of Confucianism, developed canons of poetic works that had ritual as well as aesthetic importance. More recently, thinkers struggled to find a definition that could encompass formal differences as great as those between Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales and Matsuo Bashō's Oku no Hosomichi, as well as differences in context that span from the religious poetry of the Tanakh to love poetry to rap.

Context can be critical to poetics and to the development of poetic genres and forms. For example, poetry employed to record historical events in epics, such as Gilgamesh or Ferdowsi's Shahnameh, will necessarily be lengthy and narrative, while poetry used for liturgical purposes in hymns, psalms, suras and hadiths is likely to have an inspirational tone, and elegies and tragedy are intended to invoke deep internal emotional responses. Other contexts include music such as Gregorian chants, formal or diplomatic speech, political rhetoric and invective, light-hearted nursery and nonsense rhymes, and even medical texts.

Classical and early modern Western traditions

Classical thinkers employed classification as a way to define and assess the quality of poetry. Notably, Aristotle's Poetics describes the three genres of poetry: the epic, comic, and tragic, and seeks to develop rules to distinguish the highest quality poetry of each genre based on the underlying purposes of that genre. Later aestheticians identified three major genres: epic poetry, lyric poetry and dramatic poetry, treating comedy and tragedy as subgenres of dramatic poetry. Aristotle's work was influential throughout the Middle East during the Islamic Golden Age, as well as in Europe during the Renaissance. Later poets and aestheticians often distinguished poetry from and defined it in opposition to prose, which was generally understood as writing with a proclivity to logical explication and a linear narrative structure. This does not imply that poetry is illogical or lacks narration, but rather that poetry is an attempt to render the beautiful or sublime without the burden of engaging the logical or narrative thought process. English Romantic poet John Keats termed this escape from logic "Negative Capability." This "romantic" approach views form as a key element of successful poetry because form is abstract and distinct from the underlying notional logic. This approach remained influential into the twentieth century. During this period, there was also significantly more interaction among the various poetic traditions, in part because of the spread of European colonialism and the attendant rise in global trade. In addition to the boom in translation, numerous ancient works were also rediscovered during the Romantic period.

Twentieth century disputes

Relying much less on the opposition of prose and poetry, some literary theorists of the twentieth-century focused on the poet as one who creates using language and poetry as what the poet creates. The underlying concept of the poet as creator is not uncommon, and some modernist poets do not significantly distinguish between the creation of a poem with words and creative acts in other media, such as carpentry. Yet other modernists challenge the very attempt to define poetry as misguided, as when Archibald MacLeish concludes his ironic poem "Ars Poetica" with the lines "A poem should not mean / but be."

Intellectual disputes over the definition of poetry and its distinction from other genres of literature were inextricably intertwined with the debate over the role of poetic form. The rejection of traditional forms and structures for poetry that began in the first half of the twentieth century coincided with a questioning of the purpose and meaning of traditional definitions of poetry and of distinctions between poetry and prose. Numerous modernist poets wrote in non-traditional forms or in what traditionally would have been considered prose, although their writing was generally infused with poetic diction and often with rhythm and tone established by non-metrical methods. While there was a significant formalist reaction within the modernist schools to the breakdown of structure, this reaction focused as much on the development of new formal structures and syntheses as on the revival of older forms and structures.

More recently, postmodernism fully embraces MacLeish's concept and tags boundaries between prose and poetry and among genres of poetry as having meaning only as cultural artifacts. Postmodernism goes beyond modernism's emphasis on the creative role of the poet to emphasize the role of the reader of a text, and to highlight the complex cultural web through which a poem is read. Poetry throughout the world today often reflects the incorporation of poetic form and diction from other cultures and from the past, further confounding attempts at definition and classification that were once sensible within a tradition such as the Western canon.

Basic elements

Prosody

Main article: Meter (poetry)Prosody is the study of the meter, rhythm, and intonation of a poem. Rhythm and meter, although closely related, should be distinguished. Meter is the abstract pattern established for a verse (such as iambic pentameter), while rhythm is the actual sound that results from a line of poetry. Thus, the meter of a line may be described as being "iambic", but a full description of the rhythm would require noting where the language causes one to pause or accelerate and how the meter interacts with other elements of the language. Prosody also may be used more specifically to refer to the scanning of poetic lines to show meter.

Methods of creating rhythm

Main articles: Timing (linguistics), tone (linguistics), and pitch accent- See also Parallelism, inflection, intonation, foot

The methods for creating poetic rhythm vary across languages and between poetic traditions. Languages are often described as having timing set primarily by accents, syllables, or moras, depending on how rhythm is established, though a language can be influenced by multiple approaches. Japanese is a mora-timed language. Syllable-timed languages include Latin, Catalan, French and Spanish. English, Russian and, generally, German are stress-timed languages. Varying intonation also affects how rhythm is perceived. Languages also can rely on either pitch, such as in Vedic or ancient Greek, or tone. Tonal languages include Chinese, Vietnamese, Norwegian, Lithuanian, and most subsaharan languages.

Metrical rhythm generally involves precise arrangements of stresses or syllables into repeated patterns called feet within a line. In Modern English verse the pattern of stresses primarily differentiate feet, so rhythm based on meter in Modern English is most often founded on the pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables (alone or elided). In the classical languages, on the other hand, while the metrical units are similar, vowel length rather than stresses define the meter. Old English poetry used a metrical pattern involving varied numbers of syllables but a fixed number of strong stresses in each line.

The chief device of ancient Hebrew Biblical poetry, including many of the psalms, was parallelism, a rhetorical structure in which successive lines reflected each other in grammatical structure, sound structure, notional content, or all three. Parallelism lent itself to antiphonal or call-and-response performance, which could also be reinforced by intonation. Thus, Biblical poetry relies much less on metrical feet to create rhythm, but instead creates rhythm based on much larger sound units of lines, phrases and sentences. Some classical poetry forms, such as Venpa of the Tamil language, had rigid grammars (to the point that they could be expressed as a context-free grammar) which ensured a rhythm. In Chinese poetry, tones as well as stresses create rhythm. Classical Chinese poetics identifies four tones: the level tone, rising tone, falling tone, and entering tone. Note that other classifications may have as many as eight tones for Chinese and six for Vietnamese.

The formal patterns of meter used developed in Modern English verse to create rhythm no longer dominate contemporary English poetry. In the case of free verse, rhythm is often organized based on looser units of cadence than a regular meter. Robinson Jeffers, Marianne Moore, and William Carlos Williams are three notable poets who reject the idea that regular accentual meter is critical to English poetry. Jeffers experimented with sprung rhythm as an alternative to accentual rhythm.

Scanning meter

Main articles: Scansion and Systems of scansionMeters in the Western poetic tradition are customarily grouped according to a characteristic metrical foot and the number of feet per line. For example, "iambic pentameter" is a meter composed of five feet per line in which the kind of feet called iambs predominate. The origin of this tradition of metrics lies in ancient Greek poetry, and poets such as Homer, Pindar, Hesiod, Sappho, and the great tragedians of Athens made use of such a metric system.

Meter is often scanned based on the arrangement of "poetic feet" into lines. In English, each foot usually includes one syllable with a stress and one or two without a stress. In other languages, it may be a combination of the number of syllables and the length of the vowel that determines how the foot is parsed. For example, in Greek, one syllable with a long unstressed vowel may be treated as the equivalent of two syllables with short vowels. In Anglo-Saxon meter, the unit on which lines are built is a half-line containing two stresses rather than a foot. Scanning meter can often show the basic or fundamental pattern underlying a verse, but does not show the varying degrees of stress, as well as the differing pitches and lengths of syllables.

As an example of how a line of meter is defined, in English language iambic pentameter, each line has five metrical feet, and each foot is an iamb, or an unstressed syllable followed by a stressed syllable. When a particular line is scanned, there may be variations upon the basic pattern of the meter; for example, the first foot of English iambic pentameters is quite often inverted, meaning that the stress falls on the first syllable. The generally accepted names for some of the most commonly used kinds of feet include:

- spondee — two stressed syllables together

- iamb — unstressed syllable followed by a stressed syllable

- trochee — one stressed syllable followed by an unstressed syllable

- dactyl — one stressed syllable followed by two unstressed syllables

- anapest — two unstressed syllables followed by one stressed syllable

The number of metrical feet in a line are described in Greek terminology as follows:

- dimeter — two feet

- trimeter — three feet

- tetrameter — four feet

- pentameter — five feet

- hexameter — six feet

- heptameter — seven feet

- octameter — eight feet

There are a wide range of names for other types of feet, right up to a choriamb of four syllable metric foot with a stressed syllable followed by two unstressed syllables and closing with a stressed syllable. The choriamb is derived from some ancient Greek and Latin poetry. Languages which utilize vowel length or intonation rather than or in addition to syllabic accents in determining meter, such as Ottoman Turkish or Vedic, often have concepts similar to the iamb and dactyl to describe common combinations of long and short sounds.

Each of these types of feet has a certain "feel," whether alone or in combination with other feet. The iamb, for example, is the most natural form of rhythm in the English language, and generally produces a subtle but stable verse. The dactyl, on the other hand, almost gallops along. And, as readers of The Night Before Christmas or Dr. Seuss realize, the anapest is perfect for a light-hearted, comic feel.

There is debate over how useful a multiplicity of different "feet" is in describing meter. For example, Robert Pinsky has argued that while dactyls are important in classical verse, English dactylic verse uses dactyls very irregularly and can be better described based on patterns of iambs and anapests, feet which he considers natural to the language. Actual rhythm is significantly more complex than the basic scanned meter described above, and many scholars have sought to develop systems that would scan such complexity. Vladimir Nabokov noted that overlaid on top of the regular pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables in a line of verse was a separate pattern of accents resulting from the natural pitch of the spoken words, and suggested that the term "scud" be used to distinguish an unaccented stress from an accented stress.

Common metrical patterns

Main article: Meter (poetry)Different traditions and genres of poetry tend to use different meters, ranging from the Shakespearian iambic pentameter and the Homerian dactylic hexameter to the Anapestic tetrameter used in many nursery rhymes. However, a number of variations to the established meter are common, both to provide emphasis or attention to a given foot or line and to avoid boring repetition. For example, the stress in a foot may be inverted, a caesura (or pause) may be added (sometimes in place of a foot or stress), or the final foot in a line may be given a feminine ending to soften it or be replaced by a spondee to emphasize it and create a hard stop. Some patterns (such as iambic pentameter) tend to be fairly regular, while other patterns, such as dactylic hexameter, tend to be highly irregular. Regularity can vary between language. In addition, different patterns often develop distinctively in different languages, so that, for example, iambic tetrameter in Russian will generally reflect a regularity in the use of accents to reinforce the meter, which does not occur or occurs to a much lesser extent in English.

Some common metrical patterns, with notable examples of poets and poems who use them, include:

- Iambic pentameter (John Milton, Paradise Lost)

- Dactylic hexameter (Homer, Iliad; Ovid, The Metamorphoses)

- Iambic tetrameter (Andrew Marvell, "To His Coy Mistress")

- Iambic tetrameter (Aleksandr Pushkin, Eugene Onegin)

- Trochaic octameter (Edgar Allan Poe, "The Raven")

- Anapestic tetrameter (Lewis Carroll, "The Hunting of the Snark"; Lord Byron, Don Juan)

- Alexandrine, also known as iambic hexameter (Jean Racine, Phèdre)

Rhyme, alliteration and assonance

Rhyme, alliteration, assonance and consonance are each methods for creating repetitive patterns of sound. These methods may be used as an independent structural element of a poem, to reinforce rhythmic patterns, or as a merely ornamental element of poem. Rhyme consists of identical ("hard rhyme") or similar ("soft rhyme") sounds placed at the end of lines or at predictable locations within lines ("internal rhyme"). Languages vary in the richness of their rhyming structures, so that Italian, for example, has a rich rhyming structure where it is possible to maintain a limited set of rhymes throughout a lengthy poem. The richness results from having word endings which follow regular forms. English, with irregular word endings adopted from many other languages, is less rich in rhyme. The richness of rhyming structures in a language plays a significant role in determining what poetic forms are commonly used.

Alliteration and assonance played a key role in structuring early Germanic, Norse and Old English forms of poetry. The alliterative patterns of early Germanic poetry interweave meter and alliteration as a key part of their structure, so that the metrical pattern determines when the listener expects instances of alliteration to occur. This can be compared to an ornamental use of alliteration in most Modern European poetry, where alliterative patterns are not formal or carried through full stanzas. Alliteration is particularly useful in languages with less rich rhyming structures. Assonance, where the use of similar verb sounds within a word rather than similar sounds at the beginning or end of a word, was widely used in skaldic poetry, but goes back to the Homeric epic. Because verbs carry much of the pitch in the English language, assonance can loosely evoke the tonal elements of Chinese poetry and so is useful in translating Chinese poetry. Consonance occurs where a consonant sound is repeated throughout a sentence without putting the sound only at the front of a word. Consonance provokes a more subtle effect than alliteration and so is less useful as a structural element.

Rhyming schemes

Main article: Rhyme schemeIn many languages, including modern European languages and Arabic, poets use rhyme in set patterns as a structural element for specific poet forms, such as ballads, sonnets and rhyming couplets. However, the use of structural rhyme is not universal even within the European tradition. Much modern poetry avoids traditional rhyme schemes. Classical Greek and Latin poetry did not use rhyme. Rhyme entered European poetry in the High Middle Ages, in part under the influence of the Arabic language in Al Andalus (modern Spain). Arabic language poets have always used rhyme extensively, most notably in their long, rhyming qasidas. Some rhyming schemes have become associated with a specific language, culture or period, while other rhyming schemes have achieved use across languages, cultures or time periods. Some forms of poetry carry a consistent and well-defined rhyming scheme, such as the chant royal or the rubaiyat, while other poetic forms have variable rhyme schemes.

Most rhyme schemes are described using letters that correspond to sets of rhymes, so if the first, second and fourth lines of a quatrain rhyme with each other and the third line does not rhyme, the quatrain is said to have an "a-a-b-a" rhyme scheme. This rhyme scheme is the one used, for example, in the rubaiyat form. Similarly, an "a-b-b-a" quatrain (what is known as "enclosed rhyme") is used in such forms as the Petrarchan sonnet. Some types of more complicated rhyming schemes have developed names of their own, separate from the "a-b-c" convention, such as the ottava rima and terza rima, discussed below. The types and use of differing rhyming schemes is discussed further in the main article.

- Ottava rima

- The ottava rima is a poem with a stanza of eight lines with an alternating a-b rhyming scheme for the first six lines followed by a closing couplet first used by Boccaccio. This rhyming scheme was developed for heroic epics but has also been used for mock-heroic poetry.

- Dante and terza rima

Dante's Divine Comedy is written in terza rima, where each stanza has three lines, with the first and third rhyming, and the second line rhyming with the first and third lines of the next stanza (thus, a-b-a / b-c-b / c-d-c, etc.) in a chain rhyme. The terza rima provides a flowing, progressive sense to the poem, and used skillfully it can evoke a sense of motion, both forward and backward. Terza rima is appropriately used in lengthy poems in languages with rich rhyming schemes (such as Italian, with its many common word endings).

Poetic form

Poetry usually depends less on sentences and particularly paragraphs than prose. The major structural elements of poetry generally are the line, the stanza or verse paragraph, and larger combinations of stazas or lines such as cantos, though the broader visual presentation of words and calligraphy can also be utilized. The basic units of poetic form are often combined into larger structures, called poetic forms, such as the sonnet.

Lines

Poetry is often separated into lines on a page. These lines may be based on the number of allocated metrical feet, or may emphasize a rhyming pattern at the ends of lines. But lines may serve other functions, particularly where poetry is not written in a formal metrical pattern. Lines can be used to separate, compare or contrast thoughts expressed in different units, or to highlight a change in pitch or tone. The relationship of lines of a poem to other units of sense, such as coherent phrases or sentences, can create dynamic tension in a poem. For example, in the well-known line from William Shakespeare's The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark, the line "To be, or not to be: that is the question" has two clear and coherent phrases separated by the pause known as a caesura, which reinforces the rhythm. However, in the same speech, another line ends mid-phrase or sentence in order to increase the tension while simultaneously pushing the reader forward (a technique called enjambment):

- Whether 'tis nobler in the mind to suffer

- The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune

Lines may be combined into couplets, or a combinations of two lines which may or may not relate to each other by rhyme or rhythm. For example, a couplet may be two lines with identical meters which rhyme or two lines held together by a common meter alone. Lines also may be combined into triplets, or sets of three lines. Sets of lines are often separated into longer stanzas, described below, which show larger and more complex relationships among the lines, and which often have related couplets or triplets within them.

Stanzas and verse paragraphs

Main article: stanzaRelated lines of poems are often organized into stanzas, which are denominated by the number of lines included. Thus a collection of four lines is a quatrain, six lines is a sestet and eight lines is an octet. Two lines form a couplet (or distich), three lines a triplet or tercet, and five lines a quintain (or cinquain). Other poems may be organized into a verse paragraphs, in which regular rhymes with established rhythms are not used, but the poetic tone is instead established by a collection of rhythms, alliterations, and rhymes established in paragraph form. Many medieval poems were written in verse paragraphs, even where regular rhymes and rhythms were used.

In many forms of poetry, stanzas are interlocking, so that the rhyming scheme or other structural elements of one stanza determine those of succeeding stanzas. Examples of such interlocking stanzas include, for example, the ghazal and the villanelle, where a refrain (or, in the case of the villanelle, refrains) is established in the first stanza which then repeats in subsequent stanzas. Related to the use of interlocking stanzas is their use to separate thematic parts of a poem. For example, the strophe, antistrophe and epode of the ode form are often separated into one or more stanzas. In such cases, or where structures are meant to be highly formal, a stanza will usually form a complete thought, consisting of full sentences and cohesive thoughts.

In some cases, particularly lengthier formal poetry such as some forms of epic poetry, stanzas themselves are constructed according to strict rules and then combined. In skaldic poetry, the dróttkvætt stanza had eight lines, each having three "lifts" produced with alliteration or assonance. In addition to two or three alliterations, the odd numbered lines had partial rhyme of consonants with dissimilar vowels, not necessarily at the beginning of the word; the even lines contained internal rhyme in set syllables (not necessarily at the end of the word). Each half-line had exactly six syllables, and each line ended in a trochee. The arrangement of dróttkvætts followed far less rigid rules than the construction of the individual dróttkvætts.

Visual presentation

Even before the advent of printing, the appearance of written poetry often added significant meaning or depth. Acrostic poems included clues or meanings in the letters beginning lines or in other specific places in a poem. In Arabic, Hebrew, and Chinese poetry, the presentation of the poems in fine calligraphy has always been an important part of the overall artistic and poetic effect. With the advent of printing, poets gained greater control over the visual presentation of their work. As a result, the use of visual elements became an important part of the poet's toolbox. Modernist poetry tends to take this to an extreme, with the placement of individual lines or groups of lines on the page forming an integral part of the poem's composition. In its most extreme form, this leads to concrete poetry or asemic writing.

Poetic diction

Poetic diction describes the manner in which language is used and refers not only to the sound but also to the underlying meaning and its interaction with sound and form. Many languages and poetic forms have very specific poetic dictions, to the point where separate grammars and dialects are used specifically for poetry. Poetic diction can include rhetorical devices such as simile and metaphor, as well as tones of voice, such as irony. Aristotle wrote in the Poetics that "the greatest thing by far is to be a master of metaphor". Since the rise of Modernism, some poets have opted for a poetic diction that deemphasizes rhetorical devices, attempting the direct presentation of things and experiences and the exploration of tone. On the other hand, Surrealists have pushed rhetorical devices to their limits, making frequent use of catachresis.

Allegorical stories are central to the poetic diction of many cultures, and were prominent in the west during classical times, the late Middle Ages and Renaisance. Rather than being fully allegorical, a poem may contain symbols or allusion that deepens the meaning or impact of its words without constructing a full allegory. Another strong element of poetic diction can be the use of vivid imagery for effect. The juxtaposition of unexpected or impossible images is, for example, a particularly strong element in surrealist poetry and haiku. Vivid images are often endowed with symbolism as well.

Many poetic dictions will use repetitive phrases for effective, either a short phrase (such as Homer's "rosy-fingered dawn") or a longer refrain. Such repetition can add a somber tone to a poem, as in many odes, or can be laced with irony as the context of the words change. For example, in Antony's famous eulogy to in Shakespeare's Julius Caesar, Anthony's repetition of the words "for Brutus is an honorable man" moves from a sincere tone to one that exudes irony.

Common poetic forms

Historically, very specific and formalized poetic forms have been developed by many cultures. In more developed, closed or "received" forms, rhyming scheme, meter and other elements of a poem are based on sets of rules, ranging from the relatively loose rules that govern the construction of an elegy to the highly formalized structure of the ghazal or villanelle. Below are described some common forms of poetry widely used across several languages. Additional forms of poetry can be found in the discussions of poetry of particular cultures or periods or in the glossary.

Sonnets

Main article: SonnetAmong the most common form of poetry through the ages is the sonnet, which, by the thirteenth century, was a poem of fourteen lines following a strict rhyme scheme and logical structure. The conventions associated with the sonnet have changed during its history, and so there are several different sonnet forms. Traditionally, English poets use iambic pentameter when writing sonnets, with the Spenserian and Shakespearean sonnets being especially notable. In the Romance languages, the hendecasyllable and Alexandrines are the most widely used meters, although the Petrarchan sonnet has been used in Italy since the 14th century. Sonnets are particularly associated with love poetry, and often use a poetic diction heavily based on heavy imagery, but the twists and turns associated with the move from octave to sestet and to final couplet make them a useful and dynamic form for many subjects. Shakespeare's sonnets are among the most famous in English poetry, with 20 being included in the Oxford Book of English Verse.

Jintishi

- Main article: Jintishi

The jintishi (近體詩) is a Chinese poetic form based on a series of set tonal patterns using the four tones of the classical Chinese language in each couplet: the level, rising, falling and entering tones. The basic form of the jintishi has eight lines in four couplets, with parallelism between the lines in the second and third couplets. The couplets with parallel lines contain contrasting content but an identical grammatical relationship between words. Jintishi often have a rich poetic diction, full of allusion, and can have a wide range of subject, including history and politics. One of the masters of the form was Du Fu, who wrote during the Tang Dynasty in the 8th century. There are several variations on the basic form of the jintishi.

Villanelle

Main article: VillanelleThe Villanelle is a nineteen-line poem made up of five triplets with a closing quatrain; the poem is characterized by having two refrains, initially used in the first and third lines of the first stanza, and then alternately used at the close of each subsequent stanza until the final quatrain, which is concluded by the two refrains. The remaining lines of the poem have an a-b alternating rhyme. The villanelle has been used regularly in the English language since the late nineteenth century by such poets as Dylan Thomas, W.H. Auden, and Elizabeth Bishop. It is a form that has gained heavier use at a time when the use of received forms of poetry has generally been declining.

Tanka

- Main article: Tanka

The Tanka is a form of Japanese poetry, generally not possessing rhyme, with five lines structured in a 5-7-5 7-7 patterns. The 5-7-5 phrase (the "upper phrase") and the 7-7 phrase (the "lower phrase") generally show a shift in tone and subject matter. Tanka were written as early as the Nara period by such poets as Kakinomoto no Hitomaro, at a time when Japan was emerging from a period where much of its poetry followed Chinese form. Tanka was originally the shorter form of Japanese formal poetry, and was used more heavily to explore personal rather than public themes. It thus had a more informal poetic diction. By the 13th century, Tanka had become the dominant form of Japanese poetry, and it is still widely written today.

Ode

Main article: OdeOdes were first developed by poets writing in ancient Greek, such as Pindar, and Latin, such as Horace, and forms of odes appear in many of the cultures influenced by the Greeks and Latins. The ode generally has three parts: a strophe, an antistrophe, and an epode. The antistrophes of the ode possess similar metrical structures and, depending on the tradition, similar rhyme structures. In contrast, the epode is written with a different scheme and structure. Odes have a formal poetic diction, and general dealing with a serious subject. The strophe and antistrophe look at the subject from different, often conflicting, perspectives, with the epode moving to a higher level to either view or resolve the underlying issues. Odes are often intended to be recited or sung by two choruses (or individuals), with the first reciting the strophe, the second the antistrophe, and both together the epode. Over time, differing forms for odes have developed with considerable variations in form and structure, but generally showing the original influence of the Pindaric or Horatian ode. One non-Western form which resemble the ode is the qasida in Arabic and Persian poetry.

Ghazal

Main article: GhazalThe ghazal (Arabic: غزل) is a form of poetry common in Arabic, Persian and Urdu poetry, among others. In classic form, the ghazal has from five to fifteen rhyming couplets that share a refrain at the end of the second line (which need be of only a few syllables). Each line has an identical meter, and there is a set pattern of rhymes in the first couplet and among the refrains. Each couplet forms a complete thought and stands alone, and the overall ghazal often reflects on a theme of unattainable love or divinity. The last couplet generally includes the signature of the author. Like other forms with a long history in many languages, many variations have been developed, including forms with a quasi-musical poetic diction in Urdu. Ghazals have a classical affinity with Sufism, and a number of major Sufi religious works are written in ghazal form. The relatively steady meter and the use of the refrain produce an incantatory effect, which complements Sufi mystical themes well. Among the masters of the form is the Persian poet Rumi.

See also

Notes

- Aristotle's Poetics, Heath (ed) (1997), further discussed below.

- See, for example, Kant's Critique of Judgment, discussed below.

- Dylan Thomas, Quite Early One Morning, discussed below.

- Many scholars, particularly those researching the Homeric tradition and the oral epics of the Balkans, suggest that early writing shows clear traces of older oral poetic traditions, including the use of repeated phrases as building blocks in larger poetic units. For one recent summary discussion, see Frederick Ahl, The Odyssey Re-Formed (1996). Others have suggested that the very earliest writing is primarily economic in nature, and that while oral poetry appears prevalent even in non-literate cultures, poetry need not necessarily predate writing. See, for example, Jack Goody, The Interface Between the Written and the Oral (1987).

- See Ahl (1996).

- N.K. Sanders, "Introduction" to Gilgamesh 1960.

- See, e.g., The Message, by Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five. (1982)

- Abolqasem Ferdowsi, Dick Davis trans., Shahnameh: The Persian Book of Kings (2006) ISBN 0670034851. Note that the Davis translation renders the Shahnameh into English prose rather than poetry, though the introduction includes an interesting discussion of the poetry and its history.

- For example, in the Arabic world, considerable diplomatic speech was carried out in poetic form through the 16th century. See Trickster's Travel's, Natalie Zemon Davis (2006).

- Poetry in political rhetoric includes the Gettysburg Address, which incorporates both rhythm and poetic diction. Examples of political invective include libel poetry and the classical epigrams of Martial and Catullus.

- For example, many of Ibn Sina's medical texts were written in verse.

- Aristotle's Poetics, Heath (ed) 1997.

- Ibn Rushd wrote a commentary on Aristotle's Poetics, replacing the original examples with passages from Arabic poets. See for example, W. F. Bogges, 'Hermannus Alemannus' Latin Anthology of Arabic Poetry,' Journal of the American Oriental Society, 1968, Volume 88, 657-70, and Charles Burnett, 'Learned Knowledge of Arabic Poetry, Rhymed Prose, and Didactic Verse from Petrus Alfonsi to Petrarch', in Poetry and Philosophy in the Middle Ages: A Festschrift for Peter Dronke, 2001. ISBN 9004119647.

- See, for example, Paul F Grendler, The Universities of the Italian Renaissance, Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004. ISBN 0801880556 (for exapmle, page 239) for the prominence of Aristotle and the Poetics on the Renaissance curriculum.

- Immanuel Kant (J.H. Bernard, trans.), Critique of Judgment (2005) at 131, for example, argues that the nature of poetry as a self-consciously abstract and beautiful form raises it to the highest level among the verbal arts, with tone or music following it, and only after that the more logical and narrative prose.

- The Challenge of Keats; Christensen, A., Crisafulli-Jones, L., Galigani, G. and Johnson, A. (eds), 2000.

- See, for example, Dylan Thomas's discussion of the poet as creator in Quite Early One Morning (1967).

- The title of "Ars Poetica" alludes to Horace's commentary of the same title. The poem sets out a range of dicta for what poetry ought to be before concluding with its classic lines.

- See, for example, the Collected Poems of William Carlos Williams or the works of Odysseus Elytis.

- See, for example, T.S. Eliot's "The Waste Land."

- See, Roland Barthes' essay "Death of the Author" in Image-Music-Text (1977).

- Robert Pinsky, The Sounds of Poetry at 52.

- See, for example, Julia Schülter, Rhythmic Grammar (2005).

- See Yip, Tone (2002), which includes a number of maps showing the distribution of tonal languages.

- Howell D. Chickering, Beowulf: a Dual-language Edition (1977)

- See, for exmample, John Lazarus (trans.), Thirukkural (Original in Tamil with English Translation) by W.H. Drew (Translator), ISBN 8120604008

- See, for example, Idiosyncracy and Technique, Marianne Moore (1966), or, for examples, William Carlos Williams, The Broken Span, New Directions (1941).

- Robinson Jeffers, Selected Poems (1965).

- Paul Fussell, Poetic Meter and Poetic Form, McGraw Hill, 1965, revised 1979. ISBN 0075536064.

- Christine Brooke-Rose, A ZBC of Ezra Pound, Faber and Faber, 1971. ISBN 0-571-091350

- The Sounds of Poetry, Robert Pinsky (1998), 11-24.

- Robert Pinsky, The Sounds of Poetry

- John Thompson, The Founding of English Meter.

- See, for example, "Yurtle the Turtle" in Yertle the Turtle and Other Stories, New York: Random House (1958); lines from "Yurtle the Turtle" are scanned in the discussion of anapestic tetrameter.

- Robert Pinsky, The Sounds of Poetry at 66.

- Vladimir Nabokov, Notes on Prosody (1964).

- Nabokov, Notes on Prosody.

- Two versions of Paradise Lost are freely available on-line from Project Guttenberg, Project Gutenberg text version 1 and Project Gutenberg text version 2.

- The original text, as translated by Samuel Butler, is available at Wikisource.

- The full text is available online both in Russian and as translated into English by Charles Johnston. Please see the pages on Eugene Onegin and on Nabokov's Notes on Prosody and the references on those pages for discussion of the problems of tranlation and of the differences between Russian and English iambic tetrameter.

- The full text of "The Raven" is available at Wikisource.

- The full text of "The Hunting of the Snark" is available at Wikisource.

- The full text of Don Juan is available on-line.

- See the Text of the play in French as well as an English translation,

- Rhyme, alliteration, assonance or consonance can also carry a meaning separate from the repetitive sound patterns created. For example, Chaucer used heavy alliteration to mock Old English verse and to paint a character as archaic, and Christopher Marlowe used interlocking alliteration and consonance of "th", "f" and "s" sounds to force a lisp on a character he wanted to paint as effeminate. See, for example, the opening speech in Tamburlaine the Great available online at Project Gutenberg.

- For a good discussion of hard and soft rhyme see the introduction of Robert Pinsky's The Inferno of Dante: A New Verse Translation (1994); his translation includes many demonstrations of the use of soft rhyme.

- Pinsky (1994).

- See the introduction to Burton Raffel, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (1984).

- Maria Rosa Menocal, The Arabic Role in Medieval Literary History (2003).

- Indeed, in translating the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, Edward FitzGerald sought to retain the scheme in English. The original text is available from the Gutenberg Porject on-line for free.etext #246

- Works by Petrarch at Project Gutenberg

- The Divine Comedy at wikisource.

- See Robert Pinsky's discussion of the difficulties of replicating terza rima in English in The Inferno of Dante: A New Verse Translation, Robert Pinsky, 1994.

- See Act III, Scene 1, available at Wikisource.

- Ibid.

- A good pre-modernist example of concrete poetry is the poem about the mouse's tale in the shape of a long tail in Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, available in Wikisource.

- See, for example, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner by Samuel Taylor Coleridge for a well-known example of symbolism and metaphor used in poetry. The albatross that is killed by the mariner is a traditional symbol of good luck, and its death takes on metaphorical implications.

- See

- The Poetics of Aristotle at Project Gutenberg at 22.

- Aesop's Fables, rendered in both verse and prose repeatedly since first being recorded about 500 B.C., are perhaps the richest single source of allegorical poetry through the ages. Other notables examples include the Roman de la Rose, a 13th-century French poem, William Langland's Piers Ploughman in the 14th century, and Jean de la Fontaine's Fables (influenced by Aesop's) in the 17th century (available in French on wikisource)..

- See Act III, Scene II in Shakespeare's The Tragedy of Julius Ceasar, available at Wikisource.

- Arthur Quiller-Couch (ed), Oxford Book of English Verse (1900). Note that the relative prominence of a poet or a set of works is often measured by reference to the Oxford Book of English Verse or the Norton Anthology of Poetry, with many people counting poems or pages allocated to a given poet or subject.

- E.g., "Do Not Go Gentle into that Good Night" In Country Sleep (1952).

- "Villanelle", Collected Poems (1945).

- "One Art," Geography III (1976).

- The extant Odes of Pindar as translated by Ernest Myers are freely available on-line from Gutenberg.

- In particular, the translations of Horace's odes by John Dryden were influential in establishing the form in English, though Dryden utilizes rhyme in his translations where Horace did not.

References

Listen to this article(2 parts, 15 minutes)

Anthologies

Main article: List of poetry anthologies- The Norton Anthology of Poetry (1994).

- Helen Gardner (ed), New Oxford Book of English Verse 1250-1950

- Donald Hall (ed), The New Poets of England and America (1957)

- Philip Larkin (ed), Oxford Book of Twentieth Century English Verse (1973)

- James Laughlin (ed), New Directions in Prose and Poetry, Annuals (1936 - 1991)

- Arthur Quiller-Couch (ed), Oxford Book of English Verse (1900).

- W.B. Yeats (ed), Oxford Book of Modern Verse 1892-1935 (1936)

Scansion and Form Alfred Corn, The Poem's Heartbeat: A Manual of Prosody (1997)

- Paul Fussell, Poetic Meter and Poetic Form, New York: Random House (1965).

- John Hollander, Rhyme's Reason (3rd ed), Yale University Press (2001)

- James McAuley, Versification, A Short Introduction (1983)

- Robert Pinsky, The Sounds of Poetry (1998).

Critical and historical works

- Cleanth Brooks, The Well Wrought Urn: Studies in the Structure of Poetry (1947)

- Cleanth Brooks, Literary Criticism: A Short History (1957)

- T.S. Eliot, The Sacred Wood: Essays on Poetry and Criticism, London, 1920.

- George Gascoigne, Certayne Notes of Instruction Concerning the Making of English Verse or Ryme

- Ezra Pound, ABC of Reading London: Faber, 1951 (first published 1934).

- Władysław Tatarkiewicz, "The Concept of Poetry," translated by Christopher Kasparek, *Dialectics and Humanism: the Polish Philosophical Quarterly, vol. II, no. 2 (spring 1975), pp. 13-24.

- John Thompson, The Founding of English Meter

Lnguistics and language

- Zhiming Bao, The structure of tone, New York: Oxford University Press (1999) ISBN 0-19-511880-4.

- Morio Kono, "Perception and Psychology of Rhythm" inAccent, Intonation, Rhythm and Pause(1997).

- Moria Yip, Tone, Cambridge textbooks in linguistics, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (2202) ISBN 0-5217-7314-8 (hbk), ISBN 0-5217-7445-4 (pbk).

Other Works

- Alex Preminger, Terry V.F. Brogan and Frank J. Warnke (Eds): The New Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics (Princeton University Press; 3rd edition, 1993). ISBN 0691021236

External links

Reference material and resources

- Glossary of Poetic Terms, from Bob's Byway

- Poetry Definitions from poetrymagic.co.uk

- Library of Congress Poetry Resources

- Poetry and Science Education

- Favorite Poem Project

- Wired for Books

Poetry collections and anthologies

- Poetry eTexts at Project Gutenberg

- The HyperTexts has poetry by the Masters, contemporary poets, Esoterica, essays, and more

- Representative Poetry Online

- Bartleby Verse

- AfroPoets Famous Black Writers

- Poets' Corner - Over 6,000 poems by over 750 poets

Poetry organizations and publications

- Academy of American Poets

- Poetry Writing

- Poets & Writers: American poetry and writing magazine

- Canadian Poetry Association

- American Poetry Review

- Contemporary Poetry Review

- The New Formalist

- Miami Poetry Review

- CUE: A Journal of Prose Poetry

- Mundo Poesía Spanish Poetry Resources