| Revision as of 22:09, 25 January 2019 view sourceIcewhiz (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users38,036 edits Per MOS:LEADLENGTH and Misplaced Pages:Article size - see talk.← Previous edit | Revision as of 22:33, 25 January 2019 view source Icewhiz (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users38,036 edits Restore pp-30-500 - removed by mistake.Next edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{POV|date=January 2019}} | {{POV|date=January 2019}} | ||

| {{pp-30-500|small=yes}} | |||

| {{use dmy dates|date=November 2018}} | {{use dmy dates|date=November 2018}} | ||

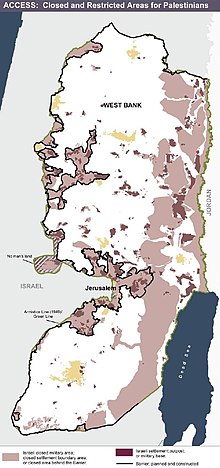

| ]; dark pink = settlements, outposts or military bases. The black line = route of the Barrier]] | ]; dark pink = settlements, outposts or military bases. The black line = route of the Barrier]] | ||

Revision as of 22:33, 25 January 2019

| The neutrality of this article is disputed. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please do not remove this message until conditions to do so are met. (January 2019) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

The Israeli occupation of the West Bank began on 7 June 1967 when Israel occupied the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and continues to the present day. The status of the West Bank as an occupied territory has been affirmed by the International Court of Justice, though the official Israeli government view is that the law of occupation does not apply and it uses the term "Disputed Territories" instead.

Among the most controversial policies enacted as part of its occupation, Israel has established numerous Israeli settlements throughout the West Bank, including East Jerusalem. The international community considers these settlements illegal under international law, though Israel disputes this. The United Nations Security Council has consistently reaffirmed that settlements in that territory are void of legality and are a "flagrant violation of international law", most recently with United Nations Security Council Resolution 2334.

The length of Israel's prolonged occupation was already regarded as "exceptional" after two decades and is now deemed to be the longest in modern history. It is widely considered to be a classic example of an "intractable" conflict. On the 50th anniversary of the occupation, Human Rights Watch stated that Israel's methods of control consist of "repression, institutionalized discrimination, and systematic abuses of the Palestinian population's rights", and involve five types of major violations of International human rights law. The broad thrust of Israeli ethnic and geopolitical policies since the foundation of the state, following Mandatory tactics, has been perceived as one intent on divide and rule (hafrayd umshol) and, in the case of West Bank Palestinians, given their ethnic unity, to exploit class and village/urban differences, and to splinter them into different factions in order to undermine their collective bargaining power, and then negotiate with the weakest actor.

Terminology and media

Main article: Media coverage of the Arab–Israeli conflictIn the immediate aftermath of the Six-Day War Israeli usage initially adopted the standard terminology of referring to the West Bank and Gaza as "occupied territories" (ha-šeṭaḥim ha-kevušim). This was soon replaced by "administered territories" (ha-šeṭaḥim ha-muḥzaqim). Finally, the West Bank area, excluding East Jerusalem, was renamed "Judea and Samaria" (Yehudah we-Šomron). Over subsequent decades, U.S. media coverage, which initially described Israel's presence in either of the Palestinian territories as an "occupation", gradually dropped the word and by 2001 it had become "almost taboo" in, and "ethereal in its absence" from, American reportage. A poll of British newsreaders that same year found that only 9% were aware that Israel was the occupying power of Palestinian territories. Israeli academic surveys at the time of Operation Defensive Shield (2002) also found that the Israeli public thought the West Bank revolt was evidence that Palestinians were trying, murderously, to wrest control of territories within Israel itself.

The quality of both Media coverage of the Arab–Israeli conflict and research and debates on university campuses have been the object of extensive monitoring and research. In the latter regard, organizations like Campus Watch closely report and denounce what they consider "anti-Israeli" attitudes. In addition to Israel's hasbara organization, intent on countering negative press images, there are also many private pro-Israeli organizations, among them CAMERA, FLAME, HonestReporting, Palestinian Media Watch and the Anti-Defamation League which subject reportage to scrutiny in the belief news on Israel has systematically distorted reality to privilege Palestinian versions. In Ehud Barak's view Palestinians are "products of a culture in which to tell a lie..creates no dissonance". Others allow that both sides lie, but "Arabs" are better at it. The term Pallywood was coined to suggest that Palestinian coverage of their plight, in a genre called "traumatic realism", is marked by a diffuse intent to fraudulently manipulate the media, beginning with the killing of Mohammad Durrah, and, it has been argued, still being evoked as late as 2014 to dismiss Israeli responsibility for the Beitunia killings. The idea has been dismissed as bearing the hallmarks of a "conspiracy theory". On the other hand, book-length studies have been devoted to testing the theory that the world's understanding of the conflict, though "mediated by Israeli newspapers to a domestic audience", is "anti-Israel".

The West Bank in 1967

Main article: Jordanian annexation of the West Bank

On the eve of occupation the West Bank accounted for 40% of Jordanian GNP, between 34% and 40% of its agricultural output and almost half of its manpower, though only a third of Jordanian investment was allocated to it and mainly to the private housing construction sector. Though its per-capita product was 10 times greater than that of the West Bank, the Israeli economy on the eve of occupation had experienced two years (1966-1967) of a sharp recession. Immediately after the occupation, from 1967 to 1974, the economy boomed. In 1967 the Palestinian economy had a gross domestic product of $1,349 per capita for a million people, with the West Bank population at 585,500, of whom 18% were refugees, and was growing annually by 2%. West Bank growth, compared to Gaza (3%), had lagged, due to the effect of mass emigration of West Bankers seeking employment in Jordan. As agriculture gave way to industrial development in Israel, in the West Bank the former still generated 37% of domestic product, and industry a mere 13%.

Local Palestinian tradition, underwritten by both Ottoman and British law, held that the land belonged to God or the sultan: families could maintain the land but the notion of private property title was alien, despite efforts since 1858 to introduce it. Until British rule which redistributed land to individual family units, village land was held collectively by the hamula or clan. The Ottoman system and all later governments until 1967 acknowledged that the land surrounding the village was for the use of its inhabitants either as common pastures or for the future development of the village. The villagers did not have any need or opportunity to register their lands. They knew among themselves which of the village lands belonged to which families and which were owned in common (mashaa ). Customary practice however under the British was reviewed to consider all land within village and town boundaries as no longer miri but mülk. By June 1967, only a third of West Bank land had been registered under the Settlement of Disputes over Land and Water Law and Israel quickly moved, in 1968, to cancel the possibility of registering one's title with the Jordanian Land Register. Claims for land in the other two thirds depended on either a Turkish or British certificate of registration, or through tax registers and proof of purchase under Jordanian law.

Conquest

Before the Six-Day War, there had been an unwritten agreement between Israel and the Jordanian government to uphold the neutrality of the border between the two countries along the Green Line. According to King Hussein, after Israel retaliated against Syrian-backed guerrilla infiltrations and sabotage by conducting on 13 November 1966 an assault on Samu in the West Bank, an area administered by Jordan, that tacit accord was broken. After Israel attacked Egypt at 8 a.m. on 5 June 1967, Jordan responded by shelling Israeli targets in West Jerusalem, and settlements along the border and then, after ignoring an Israeli warning, by attacking Israeli airfields in Ramat David and Kfar Syrkin, but also Netanya. In response, the Israeli army in a swift campaign took possession of East Jerusalem and, after news that King Hussein had ordered his forces to withdraw across the Jordan, took the entire West Bank by noon on 8 June.

Israel expelled many people from areas it had conquered, beginning with an estimated 12,000 people who on the very first day were rounded up in the villages of Imwas, Yalo and Bayt Nuba in the Latrun Salient and ordered by the Israeli military into exile eastwards. All three villages were then blown up, and within two years the area was planned as a recreational area now called Canada Park. Tens of thousands of Palestinians fled to Jordan from the refugee camps of Aqabat Jaber and Ein as-Sultan after Israel bombed the camps. The overall numbers of Palestinians displaced by that war is generally estimated to have been around 280,000-325,000, of which it has been calculated that some 120-170,000 were two-time refugees, having been displaced earlier during the 1948 war. The number who left the West Bank as a consequence of the war ranges from 100,000 to 400,000, of which from 50,000 to 200,000 lived in the Jordan Valley.

Legal status

Main article: International law and Israeli settlementsBefore proceding with settlement, the government sought legal advice from their resident expert on international law, Theodor Meron, His top secret memorandum stated unequivocally that the prohibition on any such population transfer was categorical, and that "civilian settlement in the administered territories contravenes the explicit provisions of the Fourth Geneva Convention." Gershom Gorenberg argues the documentary record indicates that the Prime Minister Levi Eshkol was therefore aware the promotion of settlements in the West Bank would be illegal. The International community has also since rejected Israel's unwillingness to accept the applicability of the Geneva Conventions to the territories it occupies, with most arguing all states are duty bound to observe them. Israel alone challenges this premise, arguing that the West Bank and Gaza are "disputed territories", and that the Conventions do not apply because these lands did not form part of another state's sovereign territory, and that the transfer of Jews into areas like the West Bank is not a government act but a voluntary movement by Israeli Jewish people, not acting under compulsion, a position contested by Yoram Dinstein.

Military Administration

Further information: Israeli Military GovernorateEven before the end of the 1967 June War, Israel invested all "powers of government, legislature, appointment and administration in relation to the region or its inhabitants" in the hands of the Military Governor. General Chaim Herzog announced on 7 June 1967, that all previously existing laws would remain in force, save in cases where they conflicted with the rights of Israel as Occupying Power to ensure security for both its forces and public order. Israel justified the retention of what it considered the Jordanian maintenance of British occupation regulations, believing them consonant with Article 64 of the Fourth Geneva Convention, which properly concern the treatment by a hostile power of the occupied population. The Jordanian position is that Israel is not heir to its laws in this regard in that they were abolished decades earlier. Called on to adjudicate between competing claims, the United Nations, in its Special Committee Report of 1970, stated that the Mandatory Defence (Emergency) Regulations of 1945, which the British themselves subsequently repealed, did not constitute a warrant for applying them to the Palestinian Territories since they were invalid, in conflicting with the protocols of the Fourth Geneva Convention.

The Israeli Military Governorate instituted to rule the territories was dissolved in 1982 and replaced by the Israeli Civil Administration, which is actually an arm of the Israeli army. Set up in November 1981 under military order no. 947, it has a mandate which stipulates that the function of the body is to "administer the civil affairs in the area ... for the welfare and benefit of the population and for provision and operation of public services, considering the need to maintain proper administration and public order in the area." The creation of this new body unleashed a wave of protest in the first few months of 1982, repressing which caused more Palestinian casualties than had occurred in the preceding 15 years of occupation. From 1967 to 2014, the Israeli administration issued over 1,680 military orders regarding the West Bank. Though formally the IDF was obliged to be neutral, it was drawn into the politics of the conflict, caught between the administration of the occupied people and the defense of settlements, which were originally thought of as a military burden whose defense should be left to the settlers, but whose early militias were salaried, trained, and furnished with arms by the IDF, which now operates to defend them.

In the Oslo Accords, Palestinian authorities were given a limited zone of autonomy in a restricted number of areas. Various analysts have argued that the agreement saw Israel outmanoeuvring the local Palestinian delegation, which had led the Intifada, by getting the PLO representatives abroad to relinquish demands the West Bank and Gaza opposition insisted on – an end to settlements and the formation of a Palestinian state – and thereby securing their own return. They were thus allowed to assume political and economic authority within the territories which they had never managed to achieve alone. Thus the Palestinian Authority itself is often viewed as a Quisling regime, or Israel's proxy, since Israel remains in total control of all three zones. Peter Beinart calls it Israel's "subcontractor". For Edward Said, Meron Benvenisti and Norman Finkelstein, the agreement merely delegated to the PLO a role as "Israel's enforcer", continuing the occupation by "remote control", lending a form of legitimacy to Israel's claims to possess "rights" in what then became in its view "disputed territories", despite the international consensus Israel was under an obligation to withdraw from all of the land it held as occupying power. In Finkelstein's reading, it ratified an extreme version of the Allon Plan. Others speak of Israel outsourcing the occupation. The Palestinian Authority also underwrote an agreement which absolved Israel of liability for recompense for all omissions to, or violations of, its obligations as an occupying power committed during the previous three decades of Israeli military rule. Indeed, were Israel convicted of any crime for that period, the burden of Israel paying reparations would fall on the Palestinian authorities who would be obligated to reimburse Israel.

Territory

East Jerusalem

Main article: East JerusalemIsrael extended its jurisdiction over East Jerusalem on 28 June 1967, suggesting internally it was annexed while maintaining abroad that it was simply an administrative move to provide services to residents. The move was deemed " null and void" by the United Nations Security Council. The Palestinian areas were encircled by Jewish new town developments which effectively closed them off from expansion, and services to the latter were kept low so that after decades, basic infrastructure was left in neglect, with shortages of schools, inadequate sewage and garbage disposal. By 2017, 370,000 lived in the overcrowded Arab areas, living under strict restrictions on their daily movement and commerce. One 2012 report stated that the effect of Israeli policies was that, amidst flourishing modern Jewish settlements, the Arab sector had been allowed to decay into a slum where criminals, many of them collaborators, thrived.

Israel's policies regarding the use of land in the rest of the West Bank display three interlocking aspects, all designed around a project of Judaization of what was Palestinian territory. These policies consist in (a) planning for land use (b) expropriations of land and (c) the construction of settlements.

Area C

Main article: Area C (West Bank)

The "Letters of Mutual Recognition" accompanying the "Israel-PLO Declaration of Principles on Interim Self-Government Arrangements" (the DOP), signed in Washington on 13 September 1993, provided for a transitional period not exceeding five years of Palestinian interim self-government in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank. Major critics of these arrangements, headed by Raja Shehadeh, argue that the PLO had scarce interest or competence in the legal implications of what it was signing.

These Oslo Accords ceded nominal control of a small amount of the West Bank to a Palestinian authority, with a provisory division of the land, excluding East Jerusalem, into 3 areas: Area A (18% of territory, 55% of population), Area B (20% of territory, 41% of the population), and Area C (62% of territory, 5.8% of population). Israel never finalized the undertaking with regard to Area C to transfer zoning and planning from the Israeli to the Palestinian authorities within five years and all administrative functions continued to remain in its hands. The areas of ostensible PA control were fragmented into 165 islands containing 90% of the Palestinian population, all surrounded by the spatially contiguous 60% of the West Bank where the PA was forbidden to venture.

In the Second Intifada in 2000, Israel reasserted a right to enter, according to "operational needs", Area A where most West Bank Palestinians live and which is formally under PA administration, meaning they still effectively control all the West Bank including areas under nominal PA authority. According to the United Nations special rapporteur on Human Rights in the Palestinian Territories, Michael Lynk, the policies applied by Israel indicate an intention to annex totally Area C, which has 86% of the nature reserves, 91% of the forests, 48% of the wells and 37% of the springs in the West Bank.

Initial impact of occupation

Soon after the 1967 Yigal Allon produced the Allon Plan, which would have annexed a strip along the Jordan River valley and excluded areas closer to the pre-1967 border, which had a high density of Palestinians. Moshe Dayan proposed a plan which Gershom Gorenberg likens to a "photo negative of Allon's." The Allon plan evolved over a period of time to include more territory. The final draft dating from 1970 would have annexed about half of the West Bank. Israel had no overall approach for integrating the West Bank: its military strategy in the war there had been piecemeal and unplanned,

Israel encouraged Arab labour to enter into Israel's economy, and regarded them as a new, expanded and protected market for Israeli exports. Limited export of Palestinian goods to Israel was allowed. 40% of the workforce commuted to Israel on a daily basis, Remittances from labourers earning a wage in Israel were the major factor in Palestinian economic growth during the 1969-73 boom years, but the migration of workers from the territories had a negative impact on local industry by creating an internal labour scarcity in the West Bank and consequent pressure for higher wages there, and the contrast between the quality of their lives and Israelis' growing prosperity stoked resentment.

Israel established a licensing system according to which no industrial plant could be built without obtaining a prior Israeli permit. The sum effect after two decades was that 15% of all Palestinian firms in the West Bank (and Gaza) employing over eight people, and 32% with less than that number of workers, were prohibited from selling their products in Israel. Israeli protectionist policies thus distorted wider trade relations to the point that, by 1996, 90% of all West Bank imports came from Israel, with consumers paying more than they would for comparable products had they been able to exercise commercial autonomy.

Land ownership

In the wake of the 1967 war, especially under the Likud governments (1977-1984), apart from expropriation, land requisitioning, zoning regulations and some purchases, Israel introduced legal definitions of what was to be regarded as "public" and what "private" land in the conquered territories.

With Military Order Number 59 issued on 31 July 1967 the Israeli commander asserted that therein state land would be whatever land had belonged to the enemy (Jordan) or its judicial bodies, and on that basis, from 1967 to 1984 the Israeli government requisitioned an estimated 5,500,000 dunams, or roughly half of the total area of the West Bank, setting aside much of the land for military training and camping areas. By defining such areas as "state land" its use by Palestinians was precluded. By 1983 the expropriation was calculated to extend over 52% of the territory, most of its prime agricultural land and, just before the 1993 Oslo Accords, these confiscations had encompassed over three quarters of the West Bank.

Many of these early confiscations took place over private Palestinian land. This led to a complaint over a settlement at Elon Moreh, and the Supreme Court ruled such practices were forbidden except for military purposes, civilians only being permitted on what Israel defined as "state land". This ruling actually enhanced the settlement project since anywhere Israelis settled automatically became a security zone requiring the military to guarantee their safety. One innovative technique in 1999 came from settlers complaining of poor cellphone reception. They pointed out a nearby hill, which they had unsuccessfully tried to colonize earlier, as an appropriate site for antennae. It was a biblical site, moreover, they claimed, though excavations only yielded Byzantine ruins. The IDF declared the antennae would pose a security issue, and then expropriated the site from its owners, the villagers of Burqa and Ein Yabrud, who grazed sheep and cultivated figs and grapes there. Settlers then moved in and established the illegal outpost of Migron.

Using the Ottoman law code regarding miri lands (only 4% of the land north of Beersheva), which held that if were not worked for 3 consecutive years without a lawful excuse they reverted to the state, Israel converted land into state land."}} In the Burqan case, where the plaintiff Mohammad Burqan's legal title to his former house in the Jewish Quarter was recognized, the Israeli Supreme Court rejected his request to be allowed to return to his home on the grounds that the area it was located in had "special historical significance" for Jews.

Settlement

Main articles: Israeli settlement and List of Israeli settlements

As of 2017, excluding East Jerusalem, 382,916 Israelis have settled in the West Bank, and 40% (approximately 170,000 in 106 other settlements) live outside the major settlement blocs, where 214,000 reside.

The technique developed over the decades of early settlement was one of incremental spread, setting up tower-and-stockade outposts, a pattern repeated in the West Bank after 1967. A quote attributed to Joseph Trumpeldor summed up Zionist logic: "Wherever the Jewish plow plows its last furrow, that is where the border will run". The principle of this slow steady establishing of "facts on the ground" before the adversary realizes what is going on, is colloquially known as "dunam after dunam, goat after goat". The model applied to the West Bank was that used for the Judaization of the Galilee, consisting of setting up a checkered pattern of settlements not only around Palestinian villages but in between them. In addition to settlements considered legal, with government sponsorship, there are some 90 Israeli outposts (2013) built by private settler initiatives. From the mid-1990s to 2015 many of these, such as Amona, Avri Ran's Giv'ot Olam and Ma'ale Rehav'am – the latter on 50 dunams of private Palestinian land – were directly funded, according to Haaretz, by loans from the World Zionist Organization through Israeli taxpayer money, since its approximate $140 million income derives from Israel and is mostly invested in settlements in the West Bank.

The International Court of Justice, established by the Rome Statute of 1998 which classified resettlement as a war crime, seconding the reiterated views of other international bodies such as the United Nations Security Council, determined in 2004 that Israeli settlements in the West Bank were established in breach of international law. In 1980, Israel declined to sign the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties which obliges national laws to give way to international law when the two conflict, and regulates settlements in terms of its own laws, in lieu of any compulsion to observe its treaty commitments and by arguing that all the relevant UN bodies adjudicating the matter are "anti-Zionist and anti-Semitic".

The first site chosen for settlement was Gush Etzion. Hanan Porat was inspirational, intending by developing the settlement in order to put in place a practical application of the radical messianic Zionism of Rabbi Zvi Yehuda Kook, whose father Abraham Isaac Kook's Mercaz HaRav yeshiva in particular has exercised considerable influence on Israel's policies regarding the West Bank. According to Eyal Benvenisti, a 1972 judgement by Supreme Court justice Moshe Landau, siding with a military commander's decision to assign electrical supply in the Hebron area to the Israel Electric Corporation rather than to a Palestinian company, was to prove pivotal to encouraging the settlement project, since it placed the latter under the jurisdiction of the military authorities.

During the first decade of Israel occupation, when the Israeli Labour Party held power, settlement was concentrated on constructing a ring of "residential fortresses" around the Palestinian population of Jerusalem, and in the Jordan Valley. According to Ibrahim Matar, the purpose of this colonizing strategy around Jerusalem was to hem in and block the expansion of the Palestinian population, and to incentivize Palestinian emigration by inducing a sense among the Palestinians a sense of living in a ghetto.

In 1972 the number of Israeli settlers in Area C were 1,200, in 1993 110,000, and in 2010 310,000 (excluding East Jerusalem). By that 2017, the fifth decade of occupation, some 237 settlements were established, housing roughly 580,000 settlers.

One technique used to established settlements was to set up a paramilitary encampment for army personnel to be used for agricultural and military training for soldiers. These were then slowly transformed into civilian settlements, often without official approval. This could be justified as legal because they were initially IDF bases without civilians. Another technique was to render land momentarily unusable. Gitit for example was established by closing off 5,000 dunams of the village lands of Aqraba and then spraying it with defoliants.

State of asymmetric war

West Bank Palestinians have engaged in two uprisings that have led to an asymmetric set of wars of attrition, between the occupying power and the occupied people. This characterization has been further refined by classifying the conflict as structurally asymmetric, where the root cause of tension lies in the standoff between a colonizer and the colonized, and in which the large power imbalance in favour of the dominator leads to a resort to guerilla tactics or terrorism by the dominated.

Armaments

The arsenal at Israel's disposal to counteract major Palestinian uprisings ranges from F-16 fighters, Merkava tanks, Apache helicopters, Hellfire missiles, massive armoured D9 Caterpillar bulldozers. to the standard M-16 rifle and the use of snipers.

The mainstay of Palestinian resistance techniques to the occupation during the First Intifada, which was generally non-lethal, consisted of throwing stones during clashes with at Israeli troops, or at military and settler vehicles bearing their distinctive yellow number plates, together with tire-burning, hurling Molotov cocktails and setting up roadblocks. The then Defense Minister Yitzhak Rabin's policy was that, "rioters must emerge with casualties or scars." The juxtaposition of this primitive method with Israeli power was striking, with children and youths throwing stones and deploying slingshots against a fully equipped and highly trained military power exerting "incredible superiority".

The military rules of engagement in the First Intifada were soon loosened to allow to be targeted for shooting stone-or Molotov throwers (or people suspecting of carrying them), youths masking their faces with keffiyeh, those building roadblocks, fleeing suspects, or anyone refusing to obey an order to halt. Israel prevented hospitals from reported statistics in the West Bank but roughly 90% of the 271 minors (16 and under) shot dead by Israeli forces between 9 December 1987 and 31 December 1993 were not throwing stones when shot, half were not taking part in clashes, 19 were executed by mista'arvim at close range for simply writing graffiti or for being masked, and 44 were denied medical treatment while lying mortally wounded.

The sentences of Palestinian prisoners are commonly based on an accusation that they are "members of illegal organizations" (meaning formerly the PLO, and now Hamas or Islamic Jihad), planning or taking part in sabotage against Israelis, or raising a Palestinian flag. Under Israeli Military Order 101, Palestinians under military law were prohibited from demonstrating and publishing anything relating to a "political matter." Surveillance of the internet, using software to ostensibly identify in social media posts potential threats led to the arrest of 800 Palestinians both by Israeli units and PA security forces, with 400 detained as "lone wolf terrorists" for what they wrote, though none had carried out attacks and, according to security expert, Ronen Bergman, no algorithm could identity lone-wolf attackers.

Violence and resistance (mūqāwama)

Two uprisings to "shake off", the literal translation of the root of the Arabic word intifada, the occupying power have so far been undertaken: the First Intifada and the Al Aqsa Intifada. The first Intifada was relatively unarmed, though Israeli soldiers were permitted to shoot at anyone throwing stones, building barricades, wearing masks or lighting tires. It was this uprising which led the Israeli government eventually to underwrite the Oslo Accords, which however did not put an end to the primary demands of the territories' Palestinian resistance movement. To the contrary, rather than freezing settlement, Israel managed to double the Jewish West Bank population from 1993 to 2000, while seizing more land, which led to popular disenchantment with the PA, seen as abetting Israel's occupational policies rather than resisting them. In the 24 months following its outbreak, 656 Palestinians died as a result of Israeli actions: 601 from gunfire, and 55 from non-bullet causes (mainly beatings). An additional 82 died from tear gas. 45 Israelis, as well as 150 Palestinians suspected of collaboration with the authorities, also died.

International law does not address the issue regarding the rights of an occupied people to resist an occupation which flagrantly violates fundamental human rights. The United Nations General Assembly Resolution 1514 established that force may not be used to deny self-determination, and that recourse to force to resist colonial or alien domination is legitimate.

The primary value developed by Palestinians to resist the occupation from 1967 has been ṣumūd, hanging on stubbornly, a steadfast perseverance in remaining on one's land, even if it turns into a prison, in the face of Jewish hitnahalut (settlement). The word itself was consistently repressed from Palestinian papers by Israeli censors in the early decades.

- Palestinians killed in the first Intifada 31/9/1987-13/9/1993.

By Israeli Defense Forces Minors under 17 By settlers 1070 237 54

- Israelis killed in the First Intifada by Palestinians.

Civilians by militants Minors under 17 Security Personnel 47 3 43

- West Bankers killed from the Second Intifada to Operation Cast Lead.(29/9/2000-26/12/2008)

Killed Minors under 17 By settlers 1793 317 40

Of the 1793, B'Tselem states 835 did not participate in hostilities; 472 did, and it is not known if the remaining 404 were involved in events of conflict or not. The equivalent number of deaths in the United States would be more than 165,000 persons—at least 55 times the number killed in New York, Washington, and Pennsylvania on 11 September 2001.

- Israelis killed in the West Bank from the Second Intifada to Operation Cast Lead.(29/9/2000-26/12/2008)

Civilians Killed Minors under 17 Soldiers killed 201 35 146

After the takeover of Gaza by Hamas many Israelis feared that Hamas would likewise eventually take control of the West Bank. Unilateral withdrawal came to be seen as too risky. Hamas could use the West Bank hills to infiltrate in order to carry out suicide attacks. Worse, most of Israel's cities would be in range of inexpensive short range Qassam 1 rockets.

Population transfer and deportations

According to one estimate, between 1967 and 1978 some 1,151 individuals were deported by Israel, including two whole tribes, dispatched into exile en masse from the area of the Jordan Valley in December 1967 and May 1969. To provide legal warrant for these measures, which contravene the Fourth Geneva Convention, Israel applied law 112 going back to the British Mandatory government's Defence (Emergency) Regulations which predated the Geneva Convention by 4 years. These in turn went back to military legislation devised to counteract the Palestinian war of opposition to British occupation and Jewish immigration in 1936-1939. Fathers were most frequently affected in the early days: sundering families, the practice was arrest household heads at night in their homes and take them to a desert south of the Dead Sea where they were forced, at gunpoint or gunshot, to cross over into Jordan. To this day, any Palestinian Jerusalemite can have his or her residency revoked by Israeli law if Jerusalem has not constituted, in the view of the Israeli authorities, their "centre of life" for seven consecutive years, a revocation constituting a forced population transfer that has been applied to at least 14,595 Palestinians since 1967 (2016). The PLO, inspired by the precedent of the SS Exodus, once endeavoured to sail a "Ship of Return" into Haifa harbour with 135 Palestinians Israel had deported from the territories. Mossad assassinated with a car-bomb the three senior Fatah officials organizing the event in Limassol, and then sunk the ship in the port.

Collective punishment

Collective punishment of Palestinians goes back to British mandatory techniques in suppressing the 1936-1939 revolt. and has been reintroduced and in effect since the early days of the occupation, and was denounced by Israel Shahak as early as 1974. Notoriety for the practice arose in 1988 when, in response to the killing of a suspected collaborator in the village, Israeli forces shut down Qabatiya, arrested 400 of the 7,000 inhabitants, bulldozed the homes of people suspected of involvement, cut all of its telephone lines, banned the importation of any form of food into the village or the export of stone from its quarries to Jordan, shutting off all contact with the outside world for almost 5 weeks (24 February-3 April). In 2016 Amnesty International stated that the various measures taken in the commercial and cultural heart of Hebron over 20 years of collective punishment have made life so difficult for Palestinians that thousands of businesses and residents have been forcibly displaced, enabling Jewish settlers to take over more properties.

House demolitions

Main articles: House demolition in the Israeli–Palestinian conflict and Moroccan Quarter

House demolition is considered a form of collective punishment. According to the law of occupation, the destruction of property, save for reasons of absolute military necessity, is prohibited. The practice of demolishing Palestinian houses began within two days of the conquest of the area in the Old City of Jerusalem known as the Moroccan Quarter, adjacent to the Western Wall. One of the first measures adopted, without legal authorization, on the conquest of Jerusalem in 1967 was to evict 650 Palestinians from their homes in the heart of Jerusalem, reduce their homes and shrines to rubble in order to make way for the construction of the plaza. From the outset of the occupation of the Palestinian territories down to 2015, according to an estimate by the ICAHD, it has been estimated that Israel has razed 48,488 Palestinian structures, with a concomitant displacement of hundreds of thousands of Palestinians.

Israel regards its practice as a form of deterrence of terrorism, since a militant is thereby forced to consider the effect of his actions on his family. Between September 2000 and the end of 2004, of the 4,100 homes the IDF razed in the territories, 628, housing 3,983 people were undertaken as punishment because a member of a family had been involved in the Al Aqsa insurgency. From 2006 until 31 August 2018, Israel demolished at least 1,360 Palestinian residential units in the West Bank (not including East Jerusalem), causing 6,115 people – including at least 3,094 minors – to lose their homes. 698 of these, homes to 2,948 Palestinians of whom 1,334 minors, were razed in the Jordan Valley (January 2006 – September 2017).

Violations of building codes are a criminal offense in Israeli law, and this was only extended to the West Bank in 2007. Israel has demolished or compelled the owners to demolish, 780 homes in East Jerusalem between 2004 and 2018, leaving 2,766 people of whom 1,485 minors, homeless. The number of homes demolished in the rest of the West Bank from 2006 until 30 September 2018 is estimated to be at least 1,373, resulting in homelessness for 6,133 Palestinians, including 3.103 minors.

Permits

Under Israeli military rule, almost every aspect of ordinary everyday Palestinian life was subject to pervasive military regulations, calculated to number of 1,300 by 1996, from planting trees and importing books, to house extensions. In the first two decades of occupation Palestinians were required to apply to the military authorities for permits and licenses for an enormous number of things such as a driver's license, a telephone, trademark and birth registration, and a good conduct certificate which was indispensable to obtain entry into many branches of professions and to work places, with putative security considerations determining the decision, which was delivered by an oral communication. The overwhelming source of information on security risks came from the Shin Bet which however was found to have systematically lied to courts for 16 years. Obtaining such permits has been described as a via dolorosa for the Palestinians seeking them. In 2004, only 0.14% of West Bankers (3,412 out of 2.3 million) had valid permits to travel through West Bank checkpoints.

Since 1991 Israel has never publicly clarified with clear consistent rules the criteria governing permits. To get a permit in the 1980-1990s one was required to acquire an approval stamp, each time paying a fee, from several different offices: (i) the tax office; (ii) the local police (iii) the municipality; (iv) the Village League (both of the latter often staffed by collaborators), and the Shin Bet, and even with these attachments, permission was not automatically forthcoming. One Bethlehemite, trying to get his daughter's birth registered – Palestinian birth registries are controlled by Israel – was required to obtain seven stamps from seven different government offices. The income office denied him their stamp because he was behind in his tax payments, though they were deducted automatically from his pay. His wife, using her identity papers, had to do the same rounds, and eventually a birth certificate was conceded. Even when some powers were delegated to the Palestinian Authority, the appropriate Palestinian offices were reduced to acting as "mailmen", passing on requests for permits to the Israeli Civil Administration, 80-80% of which are then rejected on unexplained "security grounds".

Israel has imposed a permit system for building in East Jerusalem and Area C which makes home construction almost impossible for Palestinian residents. It is estimated that 85 percent of the Palestinian houses in East Jerusalem are "illegal" This implies that since 1967 approximately twenty thousand buildings were built by Palestinians in East Jerusalem without acquiring sufficient building permits. Israel has excluded hundreds of thousands of Palestinians from its population register, with serious consequences for their ability to dwell in or travel from the West Bank (and Gaza). The number of Palestinians who have had their residency permits revoked from 1967 to 2017 exceeds 130,000 people in the West Bank and 14,565 in East Jerusalem.

When pieces of land are fenced off from their traditional owners, often by declaring they lie within a closed military zone or on the Israeli seam land side of the Separation Barrier, a permit from the military administration is then required for the owner to access his fields: tending such fields becomes an arduous bureaucratic and physical task with access often allowed only once a year. The practice of denying usufruct in order to allow the 10 year expiry of rights to kick in was taken to the Israeli Supreme Court which, in 2006, arguing that the denial of access custom was akin to denying a person the right to enter his own home in order to defend himself from a thief, ruled in favour of the plaintiffs, and directed the IDF to ensure everything was done to ensure Palestinians could tend their olive groves. According to Irus Braverman, however, subsequent IDF regulations, guaranteeing tree protection in designated "friction zones" (ezorei hikuch) but not anywhere else, only complicated the issue. By 2018 it was calculated that of grants to people in the West Bank of areas Israel declared to be state lands, 99.7% was given to Israeli settlements, with 0.24% (400 acres (160 ha)) being earmarked for allocation to Palestinians who constitute 88% of the population.

Impact on education

Main article: Education in the State of PalestinePalestinians traditionally place a high priority on education and by 1979 it was estimated that 10% of all Arab university graduates were Palestinian.

During the first Intifada at one point Israel imposed a 19-month closure on all schools in the West Bank, including kindergartens, suggesting to at least one observer that Israel was intentionally aiming to disrupt the cognitive development of Palestinian youths. In the first two years of the Al-Aqsa Intifada, 100 schools were fired on by the IDF, some were bombed and others occupied as military outposts.

Night raids

According to Major General Tal Rousso, the IDF undertakes operations "all the time, every night, in all divisions." Israeli night raids are usually undertaken between 2 am and 4 am. The units, whose members are often masked and accompanied by dogs, arrive in full battle gear and secure entry by banging on doors or blowing them off their hinges. Surging blips in frequency may relate to rotation of new units into an area. Most occur in villages in close proximity to settlements. Such missions have several different purposes: to arrest suspects, conduct searches, map the internal structure of a dwelling, and photograph youths to improve recognition in future clashes. Laptops and cellphones are often seized, and, if returned, not infrequently damaged. Vandalism is commonplace, with looted objects given to needy soldiers or those on low pay, as in Operation Defensive Shield. Reports of stashes of money that go missing after a search are frequent.

Arrests and administrative detention

Further information: Administrative detentionThe military court system for the occupied territories, modeled partially on the British military court system set up in 1937, was established in 1967, and had been called the institutional centerpiece of the occupation, and within it West Bank Palestinians are treated as "foreign civilians". All of the judges are Jewish Israelis.

The measures it applies, combining elements of colonial administration and martial law, cover not only incidents involving recourse to violence but many other activities, non-violent protests, political and cultural statements and the way Palestinians are allowed to move or associate with each other.

Hundreds of thousands of Palestinians have been put on trial since 1967: according to Saree Makdisi the cumulative total of Palestinian detainees imprisoned by Israel from that date down to 2005 reached 650,000. Of these, according to Tamar Pelleg-Sryck (2011), tens of thousands have been subjected to the specific treatment of administrative detention. The incarceration rate was the highest in the world during the first uprising against Israeli rule (1987-1992) – and their conviction rates varied from 90 to 95%, being for the most part secured by plea bargainings in 97% of cases. According to Red Cross statistics, in the first two decades of the occupation, from 1967 to 1987, one in three Palestinians -500,000 – were subject to arrest and detention by Israeli forces, and on any given day the courts would be crammed with "children in handcuffs, women pleading with soldiers, anxious people thronging lawyers for information." After the Oslo Accords, courts in Palestinian towns were withdrawn to Area C, which however only meant that lawyers and family for the defendants had far greater difficulty, because of the permit system, in getting access to the tribunals.

For the decade from 2000 to 2009 it was estimated that at any one time anywhere between 600 and 1,000 Palestinians were subjected annually to administrative detention. Amnesty International stated that in 2017 Israeli authorities continue to adopt administrative detention rather than criminal prosecution to detain "hundreds of Palestinians, including children, civil society leaders and NGO workers, without charge or trial under renewable orders, based on information withheld from detainees and their lawyers", and that administrative detainees numbered 441.

Torture

According to Lisa Hajjar (2005) and Dr. Rachel Stroumsa, the director of the Public Committee Against Torture in Israel, torture has been an abiding characteristic of Israeli methods of interrogation of Palestinians. Though formally banned by the High Court in 1999, legalized exceptions, authorized by the Attorney General of Israel, persist:

Torture techniques include shabeh, a practice 76% of the Israel public (1998) thought a form of torture, but only 27% opposed its use against Palestinians. This consists of being forced to sit on a very small chair, with a filthy hood over one's head, as blaring music is drummed into one's ears. It could, as with one woman, last up to 10 days, night and day; also included among torture techniques was the beating of the bare soles of detainees' feet (falaqa), or subjecting them, while deprived of sleep, to endless lectures on themes like: "All Arabs are Bedouin, and Bedouin are Saudis, so Palestinians should go back to Saudi Arabia, where they came from. You don't belong here." Blindfolding is used so that the suspect can never anticipate when he is to be struck. In the First Intifada, other than prolonged beatings, people, including children, could be smeared with vomit or urine, be confined in a "coffin", be suspended by the wrists; be denied food and water or access to toilets, or be threatened to have their sisters, wives or mothers raped. Methods, including torture, practiced also on Palestinian children were reported to persist with Amnesty International stating in 2018 that though over 1,000 complaints have been filed regarding these practices since 2001, "no criminal investigations were opened."

Children

Main article: Children in the Israeli–Palestinian conflict

Each year approximately 700 Palestinian children aged 12 to 17, the great majority of them boys, are arrested, interrogated and detained by Israeli army, police and security agents. An estimated 7,000 children have been detained, interrogated, prosecuted and/or imprisoned within the Israeli military justice system – an average of two children each day. Israel, after it emerged that even 12 year-old children were prosecuted in adult military courts, instituted in September 2009 a juvenile military court, the only one known to exist in the world, which however uses the same staff and rooms as the military courts where Palestinian adults are put on trial. Two years later (27 September 2011) Military Order 1676 stipulated that only youths 18 and over could be tried in adult military courts. However the sentencing protocols applied to the 16–17 year old bracket remain those applied to adults. Most prosecutions of teenagers concern stone-throwing which is an offence under Section 212 of Military Order 1651, and carried a penalty of up to 10 years imprisonment, theoretically applicable to children between 14 and 15. Conviction for throwing anything at a moving vehicle with intent to harm carries a maximum penalty of 20 years.

Fragmentation

The official "Master Plan for the Development of Samaria and Judea to the year 2010" (1983) foresaw the creation of a belt of concentrated Jewish settlements linked to each other and Israel beyond the Green line while disrupting the same links joining Palestinian towns and villages along the north-south highway, impeding any parallel ribbon development for Arabs and leaving the West Bankers scattered, unable to build up larger metropolitan infrastructure, and out of sight of the Israeli settlements.

One observed function of the Separation Barrier is to seize large swathes of land thought important for future settlement projects. The construction, significantly inspired by the ideas of Arnon Soffer to "preserve Israel as an Island of Westernization in a Crazy Region", had as its public rationale the idea of defending Israel against terroristic attacks, but was designed at the same time to incorporate a large swathe of West Bank Territory, much of it private Palestinian land: 73% of the area marked for inclusion into Israel was arable fertile and rich in water formerly constituting the "breadbasket of Palestine".

Legal system

Further information: Israeli law in the West Bank settlementsThe Israeli-Palestinian conflict is characterized by a legal asymmetry, which embodies a fragmented jurisdiction throughout the West Bank, where ethnicity determines what legal system one will be tried under. Down to 1967, people in the West Bank lived under one unified system of laws applied by a single judicial system. State law (qanun) is a relatively alien concept in Palestinian culture, where a combination of the Shari'a and customary law (urf) constitute the normal frame of reference for relations within the basic social unity of the clan ("hamula"). Settlers are subject to Israeli civil law, Palestinians to the occupying arm's military law. Overall the Israeli system has been described as one where "Law, far from limiting the power of the state, is merely another way of exercising it." A Jewish settler can be detained up to 15 days, a Palestinian can be detained without charges being laid for 160 days.

According to the legal framework of international law, a local population under occupation should continue to be bound by its own penal laws and tried in its own courts. However, under security provisions, local laws can be suspended by the occupying power and replaced with military orders enforced by military courts In 1988, Israel amended its Security Code in such a way that international law could no longer be invoked before the military judges in their tribunals. Israeli businesses in the West Bank employing Palestinian labour drew up employment laws according to Jordanian law. This was ruled in 2007 by the Israeli Supreme Court to be discriminatory, and that Israeli law must apply in this area, but as of 2016, according to Human Rights Watch, the ruling has yet to be implemented, and the government states that it cannot enforce compliance.

Extensive portions of Israeli civil law have been introduced to apply to settlements, their jurisdictions and settlers themselves, a system called Enclave law. The basic military laws governing the West Bank are influenced by what is called the "pipelining" of Israeli legislation. The High Court has upheld only one challenge to the more than 1,000 arbitrary military orders that have been imposed over the past two decades and that are legally binding in the occupied territories.

Freedom of movement

Main articles: Israeli checkpoint and Palestinian freedom of movementThe World Bank noted that additional costs arising from longer travelling caused by restrictions on movement through three major routes in the West Bank alone ran to (2013) USD 185 million a year, adding that other, earlier calculations (2007) suggest restrictions on the Palestinian labour market cost the West Bank approximately US$229 million per annum. It concluded that such imposed restrictions had a major negative impact on the local economy, hindering stability and growth. In 2007, official Israeli statistics indicated that there were 180,000 Palestinians on Israel's secret travel ban list. 561 roadblocks and checkpoints were in place (October), the number of Palestinians licensed to drive private cars was 46,166 and the annual cost of permits was $454. These checkpoints, together with the separation wall and the restricted networks restructure the West Bank into "land cells", freezing the flow of normal everyday Palestinian lives. Israel sets up flying checkpoints without notice. Some 2,941 flying checkpoints were rigged up along West Bank roads, averaging some 327 a month, in 2017. A further 476 unstaffed physical obstacles, such as dirt mounds, concrete blocks, gates and fenced sections had been placed on roads for Palestinian use. Of the gates erected at village entrances, 59 were always closed.

Between 1994 and 1997, the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) built 180 miles of bypass roads in the territories, on appropriated land because they ran close to Palestinian villages. The given aim was said to be to afford protection to settlers from Palestinian sniping, bombing, and drive-by shootings. Though prohibited by law, confiscation of Palestinian identity cards at checkpoints is a daily occurrence. At best drivers must wait for several hours for them to be returned, when, as can happen, the IDs themselves are lost as soldiers change shifts, in which case Palestinians are directed to some regional office the next day, and more checkpoints to get there.

Village closures

Main article: West Bank closuresThe closure (Hebrew seger, Arabic ighlaq) policy operates on the basis of a pass system developed in 1991, and is divided into two types: a general closure restriction the movement of goods and people, except when a permit is given, from and to Israel and the West Bank and Gaza, developed in response to a series of stabbings in the former 1993, and the implementation of total closure over both areas. Aside from general closures, total closures were imposed for over 300 days from September 1993 after the Declaration of Principles of the Oslo I Accord and late June 1996. The strictest total closure was put in place in the spring of 1996 in the wake of a series of the suicide bombings executed by the Gaza-Strip based organization of Hamas in retaliation for the assassination of Yahya Ayyash, when the Israeli government imposed a total 2 week long ban on any movement by over 2 million Palestinians between 465 West Bank towns and villages, a measure repeated after the deadly clashes arising from the archaeological excavations under the Western Wall of the Haram al Sharif/Temple Mount. The IDF erected iron gates at the entrances to the overwhelming majority of Palestinian villages, allowing the army to shut them down at will, in minutes.

Marriage difficulties

In practice, Israel evaluates proposed family reunifications in terms of a perceived demographic or security threat. They were frozen in 2002. Families composed of a Jerusalemite spouse and a Palestinian from the West Bank (or Gaza) face enormous legal difficulties in attempts to live together, with most applications, subject to an intricate, on average decade-long, four-stage processing, rejected. Women with "foreign husbands" (those lacking a Palestinian identity card), are reportedly almost never allowed to rejoin their spouse. The 2003 Citizenship and Entry into Israel Law (Temporary Provision), or CEIL, subsequently renewed in 2016 imposed a ban on family unification between Israeli citizens or "permanent residents" and their spouses who are originally of the West Bank or Gaza. Such a provision does not apply, however, to Israeli settlers in the West Bank or (until 2005) Gaza. In such instances, the prohibition is explained in terms of "security concerns". A Jerusalemite Palestinian who joins their spouse in the West Bank and thereby fails to maintain seven years of consecutive residence in East Jerusalem can have their residency right revoked.

Targeted assassinations

Main articles: Israeli targeted killings and List of Israeli assassinationsTargeted assassinations are acts of lethal selective violence undertaken against specific people identified as threats. Rumours emerged in the press around September 1989 that Israel had drawn up a wanted list, several of whom were subsequently killed, and it was speculated that the time Israel might be operating "death squads". In its decision regarding the practice, the Israeli Supreme Court in 2006 refrained from either endorsing or banning the tactic, but set forth four conditions – precaution, military necessity, follow-up investigation and proportionality- and stipulated that the legality must be adjudicated on a case by case analysis of the circumstances.

Israel first publicly acknowledged its use of the tactic at Beit Sahour near Bethlehem in November 2000, when four lasar-guided missiles from an Apache helicopter were used to liquidate a Tanzim leader, Hussein Abayat, in his Mitsubishi pick-up truck, with collateral damage killing two 50 year-old housewives waiting for a taxi nearby, and wounding six other Palestinians in the vicinity. The public admission was due to the fact an attack helicopter had been used, which meant the execution could not be denied, something that remains possible when assassinations of activists by snipers takes place. According to B'Tselem, an Israeli human rights organization, for the period between 2000 and the end of 2005, 114 civilians died as the result of collateral damage as Israeli security forces successfully targeted 203 Palestinian militants. The figures from 9 November 2000 to 1 June 2007 indicate that Israeli assassinations killed 362 people, 237 being directly targeted and 149 bystanders collaterally.

Surveillance

Israel, in its capillary monitoring of Palestinians has been called a Surveillance state par excellence. Soon after hostilities ceased, Israel began to count all items in households from televisions to refrigerators, stoves down to heads of livestock, orchards and tractors. Letters were checked and their addresses registered, and inventories were drawn up of workshops producing furniture, soap, textiles, sweets and even eating habits. While many innovations were introduced to improve workers' productivity, they can also be seen as control mechanisms. Israeli surveillance and strike presence over Palestinian areas is constant and intense, with former Shin Bet head Avi Dichter noting, "When a Palestinian child draws a picture of the sky, he doesn't draw it without a helicopter."

Censorship

In the West Bank both the British Mandatory "Defense Emergency Regulations of 1945, No. 88" – stipulating that "every article, picture, advertisement, decree and death notice must be submitted to military censors", – and "Israeli Military Order No. IOI (1967)", amended by "Order No. 718 (1977)" and "No. 938 (1981)" concerning "the prohibition of incitement and adverse propaganda" formed the basis for censoring West Bank publications, poetry and literary productions. The problem was that no guidelines clarified precisely what could or could not be said, and even articles translated directly from the Hebrew press could be prohibited, or love poems free of any nationalistic undertone could be suppressed from publication by a censor, or theatrical pieces approved in Israel could be blocked by arbitrary fiat by any military governor, or staging denied by simply not replying to requests for permission. Newspapers could lose their licenses, without any reason given, on the basis of 1945 Emergency Regulation (Article 92/2). There were two distinct censorship bureaus, one run by the military and the other by the civil administration, and what was allowed by one could be overturned by the other, and this double procedure applied to galley proofs of every article in newspapers. In the first decades of occupation, Palestinian publications were vetted and numerous books were censored to remove any phrase or expression which was considered as "incitement" or fostering national feelings among the Palestinians. Thus even obituaries stating that a family "in the homeland and the diaspora mourns" the deceased was struck out.

The Palestinian National Authority also uses censorship. As early as 1996 it forbade circulation of Edward Said's Peace and Its Discontents.

Coercive collaboration

One of the first things Israel captured on conquering the West Bank were the archives of the Jordanian Security Police, whose information allowed them to turn informers in the territory for that service into informers for Israel. Collaborators (asafir), broken in interrogation, and then planted in cells to persuade other prisoners to confess, began to be recruited in 1979. The number of collaborators with Israel before the Oslo Accords was estimated at around 30,000. According to Haaretz, Shin Bet has used a number of "dirty" techniques to enlist Palestinians on its payroll as informers. These methods include exploiting people who have been identified as suffering from personal and economic hardships, people requesting family reunification, or a permit for medical treatment in Israel.

Taxation

Main article: Taxation in the State of PalestineMilitary Order 31 of 27 June 1967 assigned all powers of taxation to an Israeli official appointed by the Area Commander. Israel adopted the Jordanian Income Tax Law of 1964 to levy taxes on Palestinians in the West Bank, while making notable changes to its tax rate intervals, but applied Israeli tax laws to Israeli Jews moving into settlements there. Under the Jordanian system the highest tax rate of 55% started with incomes of 8,000 dinars. The Israeli military authorities squeezed the rates so that by 1988 this applied to Palestinians earning 5,231 JD (equal to 24,064 Israeli shekels, whereas in Israel the 48% rate only applied to Israeli wage earners earning nearly double that amount (45,600 shekels). This discrimination did not affect Israeli West Bank settlers, who were allowed to be taxed at the lower rates operant in Israel. Similarly the self-employed West Bankers appeared to pay more than their Israeli counterparts, but due to the different deductibility regimes, clearer conclusions about discriminations could not be ascertained.

Access to most public services in areas under Israeli control is conditional on proof one is not in arrears with paying one's taxes, income, property and value-added (VAT) and fines, to the military administration. The bureaucratic process is cumbersome and arbitrary. This system was legalized in the West Bank retroactively under two military order No. 1262 (17 December 1988). Israel's taxation allows broad leeway and discretion, taking in norms of appeal and the taxpayer's rights. The draconian provisions of Section 194 of the Israeli Income Tax Ordinance, allowing taxation officers to assess what a taxpayer may owe while limiting challenges, and making them conditional on the prior payment of a bond, rarely applied in Israel, has been routine in the West Bank. Likewise, imprisonment for tax offenses is uncommon in Israel but, according to Lazar, "in the territories it is used on a massive scale and for extensive periods of time." Palestinians deeply resented paying taxes on their business and commercial activities to the Occupation authority without receiving the same benefits Israeli taxpayers had in return. In the First Intifada, tax payments dropped 50%, and Israel responded by cutting health benefits.

Agriculture

Main article: Agriculture in the Palestinian territoriesThe pastoral economy was a fundamental wing of the Palestinian economy. Of the 2,180 square kilometres (840 sq mi) of grazing land in the West Bank Israel permitted in the first years of the 21st century only 225 square kilometres (87 sq mi) for such use. In certain areas, such as the South Hebron Hills, Palestinian bedouin shepherds have their grazing lands disseminated with poison pellets that kill off their flocks, and require minute gleaning and disposal to restore the land to health. In Area C, nearly 500,000 dunams of arable land exist, Palestinian access to which is severely restricted while 137,000 are cultivated or occupied by Israeli settlements. Were the 326,400 dunams theoretically open to Palestinian use made available, the World Bank calculates, it would add $US 1,068 billion to Palestinian productive capacities. Another 1,000,000 dunams could be exploited for grazing or foresty, were Israel to lift its restrictions. The World Bank estimates that were Palestinian agriculture given access to better water resources, they would benefit by a boost in agricultural output of around $1 billion per annum.

Water

The region of Israel/Palestine is "water-stressed", like many other countries in the region, and macroanalysts consider working out how to share water resources the "single most important problem" for Middle Eastern peoples. One third of all water consumed in Israel was by the 1990s drawn from groundwater that in turn came from the rains over the West Bank, and the struggle over this resource has been described as a zero-sum game. In the wake of 1967, Israel abrogated Palestinian water rights in the West Bank, and with Military Order 92 of August of that year invested all power over water management to the military authority. Both of Israel's own acquifers originate in West Bank territory and its northern cities would run dry without them. According to John Cooley, West Bank Palestinian farmers' wells, which in Ottoman, British, Jordanian and Egyptian law were a private resource owned by villages, were a key element behind Israel's post-1967 strategy to keep the area and in order to protect "Jewish water supplies" from what was considered "encroachment" many existing wells were blocked or sealed, Palestinians were forbidden to drill new wells without military authorization, which was almost impossible to obtain, and restrictive quotas on Palestinian water use were imposed. 527 known springs in the West Bank furnish (2010) Palestinians with half of their domestic consumption. The historic wells furnishing Palestinian villages have often been expropriated for the exclusive use of settlements: thus the major well servicing al-Eizariya was taken over by Ma'ale Adumim in the 1980s, while most of its land was stripped from them leaving the villagers with 2,979 of their original 11,179 dunams.

Waste

Israel, it is argued, uses the West Bank as a "sacrifice" zone for placing 15 waste treatment plants, which are there under less stringent rules that those required in Israel because a different legal system has been organized regarding hazardous materials that can be noxious to local people and the environment. The military authorities do not render public the details of these operations. These materials consist of such things as sewage sludge, infectious medical waste, used oils, solvents, metals, electronic waste and batteries. In 2007 it was estimated that 38% (35 mcm a year) of all wastewater flowing into the West Bank derived from settlements and Jerusalem.

Archaeology

An archaeological military service was instituted by Israel after the conquest. The Israeli Antiquities Law of 1978 (Law 885, Chapter 8), following on the Jordanian Provisional Antiquities Law No. 12 of 1967 allowed for the expropriation of any site if the relevant minister deemed it necessary for preservation, excavation or research. In areas under direct Israeli control, discovery of antiquities on and near Palestinian land means that the Civil Administration can deny the Palestinian owners a building permit, lead to confiscations and eventually the transformation of the land into an Israeli settlement.

Almost 60% of the West Bank's cultural archaeological heritage the lies in Area C, which falls under full Israeli control. Israel does not allow Palestinian institutes to explore, and safeguard this heritage with the result that much of the area is subject to sacking. According to the Palestinian Department of Antiquites and Cultural Heritage upwards of 120,000 objects are smuggled out of Palestine. Plundering of sites has increased dramatically on each occasion when an intifada broke out, closing off Israel to Palestinian labour. The groundwork is done by Palestinian looters, and the results funneled through Jerusalem, the main transit point for Palestinian middlemen offloading the wares on the Israeli antiquities market. Many looters regard these sites as "negative heritage" since were it retrieved it would not remain in the West Bank as part of Palestinian cultural heritage.

Tourism

The Palestinian territories contain several of the most significant sites for Muslims, Christians and Jews, and are endowed with a world-class heritage highly attractive to tourists and pilgrims. The key Palestinian towns in the West Bank for tourism are East Jerusalem, Bethlehem and Jericho. All access points are controlled by Israel and the road system, checkpoints and obstacles in place for visitors desiring to visit Palestinian towns leaves their hotels half-empty. From 92 to 94 cents in every dollar of the tourist trade goes to Israel. The general itineraries under Israeli management focus predominantly on Jewish history. Obstacles placed in the way of Palestinian-managed tourism down to 1995 included withholding licenses from tour guides, and hotels, for construction or renovation, and control of airports and highways, enabling Israel to develop a virtual monopoly on tourism.

Resource extraction

Based on the number of quarries per km in Areas A and B, it is calculated that, were Israel to lift restrictions, a further 275 quarries could be opened in Area C. The World Bank estimates that Israel's virtual ban on issuing Palestinians permits for quarries there costs the Palestinian economy at least US$241 million per year. The Oslo Accords agreed to hand over mining rights to the Palestinian Authority. Israel licenses eleven settlement quarries in the West Bank and they sell 94% of their material to Israel, which arguably constitutes "depletion" and pays royalties to its West Bank military government and settlement municipalities. Thus the German cement firm quarrying at Nahal Raba paid out €430,000 ($479,000) in taxes to the Samaria Regional Council in 2014 alone. The Israeli High Court rejected a petition that such quarrying was a violation by stating that after 4 decades Israeli law must adapt to "the realities on the ground". The state did undertake not to open more quarries. Israel has denied Palestinians permits to process minerals in that area of the West Bank.

Economic and social benefits and costs of the occupation

Many Israeli businesses operate in the West Bank, often run by settlers who enjoy the benefits of government subsidies, low rents, favourable tax rates and access to cheap Palestinian labour. Human Rights Watch claims that the "physical imprint", with 20 Israeli industrial zones covering by 2016 some 1,365 hectares, of such commercial operations, agricultural and otherwise, is more extensive than that of the settlements themselves. The restrictions on Palestinian enterprise in Area C cause unemployment which is then mopped up by industrial parks that can draw on a pool of people without job prospects if not in settlements. Some Palestinian workers at the Barkan Industrial Park have complained anonymously that they were paid less than the minimum Israeli wage per hour ($5.75), with payments ranging from $1.50 to 2-4 dollars, with shifts of up to 12 hours, no vacations, sick days, pay slips or social benefits.

The World Bank estimated that the annual economic costs to the Palestinian economy of the Israeli occupation of Area C alone in 2015 was 23% of GNP in direct costs, and 12% in indirect costs, totally 35% which, together with fiscal loss of revenue at 800 million dollars, totals an estimated 5.2 billion dollars. Fiscally, one estimate places the "leakage" of Palestinian revenue back to the Israeli treasury at 17% of total Palestinian public revenue, 3.6% of GNP.

The Paris Protocol undersigned in 1994 allowed Israel to collect VAT on all Palestinian imports and good from that country or in transit through its ports, with the system of clearance revenue giving it effective control over roughly 75% of PA income. Israel can withhold that revenue as a punitive measure, as it did in response to the decision by the PA to adhere to the International Criminal Court in 2015.

Communications

Main article: Communications in the Palestinian territoriesUnder the Oslo Accords, Israel agreed that the Palestinian territories had a right to construct and operate an independent communications network. In 2016 a World Bank analysis concluded the provisions of this agreement had not been applied, causing notable detrimental effects to Palestinian development. It took 8 years for Israel to agree to a request for frequencies for 3G services, though they were limited, causing a bottleneck which left Israeli competitors with a distinct market advantage. The local Wataniya mobile operator's competitiveness suffered from Israeli restrictions and delays, and illegal Israeli operators in the West Bank, with 4G services available by that date, still maintained an unfair advantage over Palestinian companies. Israel imposes three other constraints that hamper Palestinian competitiveness: restrictions are imposed on imports of equipment for telecom and ICT companies, and movement to improve the development and maintenance of infrastructure in Area C, and finally, Palestinian telecommunications accessing international links must go through companies with Israeli registration. From 2008 to 2016, they concluded, progress in negotiating resolutions to these problems had been "very slim".

Overall economic costs

A joint study by the Palestinian Ministry of National Economy and researchers at the Applied Research Institute–Jerusalem argued that by 2010 the costs of occupation amounted in 2010 alone rose to 84.9% of the total Palestinian GDP ($US 6.897 billion). Their estimate for 2014 states that the total economic cost of Israel's occupation amounted to 74.27% of Palestinian nominal GDP, or some $(US) 9.46 billion. The cost to Israel's economy by 2007 was estimated at $50 billion.

Notes

- On 7 June 1967, Israel issued "Proclamation Regarding Law and Administration (The West Bank Area) (No. 2)—1967" which established the military government in the West Bank and granted the commander of the area full legislative, executive, and judicial power. The proclamation kept in force local law that existed on 7 June 1967, excepting where contradicted by any new proclamation or military order.

- Jordan claimed it had a provisional sovereignty over the West Bank, a claim revoked in 1988 when it accepted the Palestinian National Council's declaration of statehood in that year. Israel did not accept this passage of a claim to sovereignty, nor asserted its counter claim, holding that the Palestinian claim of sovereignty is incompatible with the fact that Israel is, in law, a belligerent occupant of the territory. Secondly it regards the West Bank as a disputed territory on the technical argument that the Fourth Geneva Convention's stipulations do not apply since, in its view, the legal status of the territory is sui generis and not covered by international law, a position rejected by the ICJ.

- "Decisions of the Israeli Supreme Court have held that the Israeli occupation of the territories has endured far longer than any occupation contemplated by the drafters of the rules of international law".

- "The Israeli-Palestinian conflict is as prototypical case of a conflict which meets the criteria describing an intractable conflict: it is prolonged, irreconcilable, violent and perceived as having zero-game nature and total".

- "more than 90 percent of network TV reporting on the occupied territories has failed to report that the territories are occupied."

- The statement is contextualized within a general tradition, visible in the writings of many journalists and scholars, of orientalist put-downs of Arabs by Krishna, who quotes the full text."They (Palestinians) are products of a culture.. in which to tell a lie creates no dissonance. They don't suffer from the problem of telling lies that exists in Judeo-Christian culture. Truth is seen as an irrelevant category"

- "The Arab countries are often dictatorships which exist thanks to lack of transparency. Everything is based on appearances. Both parties, but in particular the Arabs, lie the whole day. You have to check their statements there on the spot."