| Revision as of 06:43, 26 February 2019 editKoraskadi (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users642 editsm →Aftermath and legacy← Previous edit | Revision as of 06:56, 26 February 2019 edit undoKoraskadi (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users642 edits →Government and culture: Reorganizing alternative view of Balhae's ruling structure.Next edit → | ||

| Line 147: | Line 147: | ||

| {{See also|List of Balhae monarchs}} | {{See also|List of Balhae monarchs}} | ||

| {{Kings of Balhae}} | {{Kings of Balhae}} | ||

| Balhae's population was composed of former Goguryeo peoples and Tungusic Mohe people in Manchuria. Because of the lack of developed agriculture also, most of the kingdom’s population was semi-nomadic.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/traditsionnye-i-innovatsionnye-mehanizmy-upravleniya-v-kochevyh-obschestvah-tsentralnoy-azii-vi-xiii-vv-chast-ii|title=Традиционные И Инновационные Механизмы Управления В Кочевых Обществах Центральной Азии VI XIII Вв. Часть II |trans-title="Traditional and innovative mechanisms of governance in the nomadic societies of Central Asia VI XIII centuries. Part II "|author=Vasyutin Sergey Aleksandrovich |work= Bulletin of Kemerovo State University |date=2015 |accessdate=5 February 2019 }}</ref> According to Lee ki-baik, the Mohe made up the working class which served the Goguryeo ruling class.<ref name="Lee Ki-baik page 88–89" /> Mohe people dominated common society, their influence was mainly restricted to providing labor.<ref>North Korea: A Country Study by Robert l. Worden</ref> |

Balhae's population was composed of former Goguryeo peoples and Tungusic Mohe people in Manchuria. Because of the lack of developed agriculture also, most of the kingdom’s population was semi-nomadic.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/traditsionnye-i-innovatsionnye-mehanizmy-upravleniya-v-kochevyh-obschestvah-tsentralnoy-azii-vi-xiii-vv-chast-ii|title=Традиционные И Инновационные Механизмы Управления В Кочевых Обществах Центральной Азии VI XIII Вв. Часть II |trans-title="Traditional and innovative mechanisms of governance in the nomadic societies of Central Asia VI XIII centuries. Part II "|author=Vasyutin Sergey Aleksandrovich |work= Bulletin of Kemerovo State University |date=2015 |accessdate=5 February 2019 }}</ref> According to Lee ki-baik, the Mohe made up the working class which served the Goguryeo ruling class.<ref name="Lee Ki-baik page 88–89" /> Mohe people dominated common society, their influence was mainly restricted to providing labor.<ref>North Korea: A Country Study by Robert l. Worden</ref> Nevertheless, there were instances of Mohe and other indigenous populations moving upward into the Balhae elite, however few, such as the followers of ], who supported the establishment of Balhae, were awarded to the title of "''Suryeong''", or "chief", which is derived from ], people from different ethnicities play a part in the ruling elite. Another view is that Goguryeo descendants did not have political dominance, and the ruling system was open to all peoples equally.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/gosudarstvennyy-apparat-korolevstva-bohay|title=Государственный аппарат королевства Бохай |trans-title="State apparatus of the kingdom of Bohai"|author1=Polutov Andrey Vadimovich |author2= |work= Siberian historical research|date=2014 |accessdate=7 February 2019 }}</ref> Its ruling structure was based on the military leader-priestly management structure of the Mohe tribes and also partly adapted elements from the Chinese system. After the 8th century, Balhae became more centralized, and power was consolidated around the king and the royal famiily.<ref name="vliev">{{cite web|url=http://contents.nahf.or.kr:8080/directory/downloadItemFile.do?fileName=jn_006_0090.pdf&levelId=jn_006&type=pdf|title=Balhae studies in Russia |author=Alexander lvliev |work= Northeast asian history foundation|date=2007 |accessdate=24 February 2019}}</ref> | ||

| After its founding, Balhae actively imported the culture and political system of the ] and the Chinese reciprocated through an account of Balhae describing it as the "flourishing land of the East (海東盛国)."<ref>{{cite web |title=渤海/海東の盛国 |url=http://www.y-history.net/appendix/wh0302-088.html|language=ja}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last1=Injae|first1=Lee|last2=Miller|first2=Owen|last3=Jinhoon|first3=Park|last4=Hyun-Hae|first4=Yi|title=Korean History in Maps|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=9781107098466|pages=64–65|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=46OTBQAAQBAJ&pg=PA64#v=onepage&q&f=false|accessdate=24 February 2017|language=en|date=2014-12-15}}</ref> The bureaucracy of Balhae was modeled after the ] and used Chinese characters to write their native language for administrative purposes.<ref name="Dillon2016"/> Balhae's aristocrats and nobility traveled to the Tang capital of ] on a regular basis as ambassadors and students, many of whom went on to pass the ].{{sfn|Crossley|1997|p=19}} Unlike Tang government, the Balhae "''taenaesang''" or the "great minister of the court" was superior to the other two chancelleries (the left and the right) and its system of five capitals originates from Goguryeo's administrative structure.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://countrystudies.us/north-korea/7.htm |title=North Korea - Silla |publisher=Countrystudies.us |date= |accessdate=2012-09-15}}</ref> | After its founding, Balhae actively imported the culture and political system of the ] and the Chinese reciprocated through an account of Balhae describing it as the "flourishing land of the East (海東盛国)."<ref>{{cite web |title=渤海/海東の盛国 |url=http://www.y-history.net/appendix/wh0302-088.html|language=ja}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last1=Injae|first1=Lee|last2=Miller|first2=Owen|last3=Jinhoon|first3=Park|last4=Hyun-Hae|first4=Yi|title=Korean History in Maps|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=9781107098466|pages=64–65|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=46OTBQAAQBAJ&pg=PA64#v=onepage&q&f=false|accessdate=24 February 2017|language=en|date=2014-12-15}}</ref> The bureaucracy of Balhae was modeled after the ] and used Chinese characters to write their native language for administrative purposes.<ref name="Dillon2016"/> Balhae's aristocrats and nobility traveled to the Tang capital of ] on a regular basis as ambassadors and students, many of whom went on to pass the ].{{sfn|Crossley|1997|p=19}} Unlike Tang government, the Balhae "''taenaesang''" or the "great minister of the court" was superior to the other two chancelleries (the left and the right) and its system of five capitals originates from Goguryeo's administrative structure.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://countrystudies.us/north-korea/7.htm |title=North Korea - Silla |publisher=Countrystudies.us |date= |accessdate=2012-09-15}}</ref> | ||

Revision as of 06:56, 26 February 2019

Ancient kingdom in northern Korean peninsula, Manchuria and the Russian Far East (698–926)| Balhae발해/渤海/Бохай | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 698–926 | |||||||||||||||

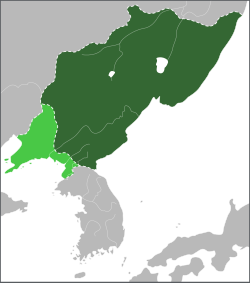

The territory of Balhae in 830, during the reign of King Seon of Balhae. The territory of Balhae in 830, during the reign of King Seon of Balhae. | |||||||||||||||

| Capital | Dongmo Mountain (698–742) Central Capital (742–756) Upper Capital (756–785) East Capital (785–793) Upper Capital (793–926) or Five Capital System (720-926) | ||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Tungusic language and Goguryeo language | ||||||||||||||

| Religion | Buddhism | ||||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||||||

| • 698–719 | Go (first) | ||||||||||||||

| • 719–737 | Mu | ||||||||||||||

| • 737–793 | Mun | ||||||||||||||

| • 794–809 | Gang | ||||||||||||||

| • 809–812 | Jeong | ||||||||||||||

| • 812–817 | Hui | ||||||||||||||

| • 818–830 | Seon | ||||||||||||||

| • 830–857 | Dae Ijin | ||||||||||||||

| • 906–926 | Dae Inseon (last) | ||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Ancient | ||||||||||||||

| • Dae Jung-sang begins military campaigns | 696 | ||||||||||||||

| • Establishment in Tianmenling | 698 | ||||||||||||||

| • "Balhae" as a kingdom name | 712 | ||||||||||||||

| • Fall of Shangjing | January 14 926 | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hangul | 발해 | ||||||||

| Hanja | 渤海 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||

| Chinese | 渤海 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Russian name | |||||||||

| Russian | Бохай | ||||||||

| Romanization | Bohai | ||||||||

| Manchu name | |||||||||

| Manchu script | ᡦᡠᡥᠠᡳ | ||||||||

| Romanization | Puhai | ||||||||

| Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Manchuria |

|

| Prehistoric period |

| Ancient to Classical period |

| Medieval to Early Modern period |

Modern period

|

Balhae (698–926), was a multi-ethnic kingdom in the Korean peninsula, Manchuria and the Russian Far East. Balhae was established by refugees from former Korean kingdom of Goguryeo, and Tungusic Mohe tribes in 698, when the first king, Dae Joyeong, defeated the Chinese Tang Dynasty at Tianmenling.

Balhae's original capital was at Dongmo Mountain in modern Dunhua, Jilin Province. In 742 it was moved to the Central Capital in Helong, Jilin. It was moved to the Northern Capital in Ning'an, Heilongjiang in 755, to the Eastern Capital in Hunchun, Jilin in 785, and back to the Northern Capital in 794. Along with Goguryeo refugees and Mohe tribes, Balhae had a diverse population, including other minorities such as Khitan, Evenk and Yilou peoples. Balhae had a high level of craftsmanship and engaged in trade with neighboring countries such as Göktürk, Japan, Silla and Tang.

In 926, the Khitan Liao dynasty conquered Balhae and established the autonomous kingdom of Dongdan ruled by the Liao crown prince Yelü Bei, which was soon absorbed into the Liao. Meanwhile, a series of nobilities and elites led by key figures such as crown prince Dae Gwang-hyeon, were absorbed into Goryeo.

According to a Chinese source, the kingdom had 100,000 households and a population of about 500,000. Archaeological evidence suggests that the Balhae culture was an amalgamation of Chinese, Korean, and indigenous cultures.

Name

Balhae was founded in 698 under the name 震, transcribed as Jin in Korean romanisation or Zhen in Chinese romanisation. The kingdom's name was written as 振 in Chinese character, with the reconstructed Old Chinese pronunciation /*ər/ and the Middle Chinese pronunciation dzyin; King Go's state wrote its name as 震, with the Middle Chinese pronunciation tsyin. The former state's character referred to the 5th Earthly Branch of the Chinese zodiac, a division of the orbit of Jupiter identified with the dragon. This was associated with a bearing of 120° (between ESE and SE) but also with the two-hour period between 7 and 9 am, leading it to be associated with dawn and the direction east.

In 713, the Tang dynasty bestowed the ruler of Jin with the title of Head of Balhae Commandery, and in 762 the Tang recognized it as a kingdom and renamed it "Balhae". There have other names for Balhae by neighboring countries, such as 靺鞨國 (Mojie state), 渤海靺鞨 (BalhaeMojie), 北國 (north state) etc.

Balhae, alternatively romanized as Parhae, is also known as Bohai in modern academia.

History

Founding

During the Khitan rebellion against Tang, Dae Jung-sang, a former Goguryeo official led Goguryeo refugees, allied with Geolsa Biu, a leader of the Mohe people, against the Tang in 698. After Dae Jungsang's death, his son, Dae Jo-yeong, a former Goguryeo general or chief of Somo Mohe succeeded his father, who received orders from the last King of Goguryeo to found a succeeding country. Geolsa Biu died in battle against the Tang army led by the general Li Kaigu. Dae Jo-yeong managed to escape Tang territory with the remaining Goguryeo and Mohe soldiers. He successfully defeated a pursuing army sent by Wu Zetian at the Battle of Tianmenling. which enabled him to establish the state of Jin in the former region of Yilou as King Go.

Another account of events suggests that there was no rebellion at all, and the leader of the Sumo Mohe rendered assistance to the Tang by suppressing Khitan rebels. As a reward the Tang acknowledged the leader as the local hegemon of a semi-independent state.

Expansion and foreign relations

The second King Mu (r. 719–737), who felt encircled by Tang, Silla and Heishui Mohe along the Amur River, ordered a punitive expedition to Tang with his navy in 732 and killed a Tang prefect based on the Shandong Peninsula. In the same time, the king led troops taking land routes to Madusan (마두산; 馬頭山) in the vincity of the Shanhai Pass (about 300 kilometres east of current Beijing) and occupied towns nearby. He also sent a mission to Japan in 728 to threaten Silla from the southeast. Balhae kept diplomatic and commercial contacts with Japan until the end of the kingdom. Balhae dispatched envoys to Japan 34 times, while Japan sent envoys to Balhae 13 times. Later, a compromise was forged between Tang and Balhae, which led Tang diplomatically recognize Mun of Balhae, who succeeded to his father's throne, as King of Balhae.

The third King Mun (r. 737–793) expanded its territory into the Amur valley in the north and the Liaodong Peninsula in the west. During his reign, a trade route with Silla, called "Sillado" (신라도; 新羅道), was established. King Mun moved the capital of Balhae several times. He also established Sanggyeong, the permanent capital near Lake Jingpo in the south of today's Heilongjiang province around 755; stabilizing and strengthening central rule over various ethnic tribes in his realm, which was expanded temporarily. He also authorized the creation of the Jujagam (주자감; 胄子監), the national academy, based on the national academy of Tang. Although China recognized him as a king, Balhae itself referred to him as the son of heaven and a king.

The tenth King Seon reign (r. 818–830), Balhae controlled northern Korea, Manchuria and what is now Primorsky Krai of Russia. King Seon led campaigns that resulted in the absorbing of many northern Mohe tribes and southwest Little Goguryeo kingdom, which was located in the Liaodong Peninsula, was absorbed into Balhae. Its strength was such that Silla was forced to build a northern wall in 721 as well as maintain active defences along the common border. In the middle of the 9th century, Balhae completed its local system, which was composed of five capitals, 15 prefectures and 62 counties.

Fall

Following the reign of King Seon (830), there is no surviving written records of Balhae. Some scholars believe that the 946 eruption of Paektu Mountain may have caused a national level catastrophe leading to its final fall to the Khitan Liao Dynasty, while other historians believe that ethnic conflicts between the ruling Goguryeos and underclass Mohe weakened the state. The Khitans were centered in Liaoning and Inner Mongolia, which overlaps Balhae's purported territories in the west. A Khitan invasion took the capital of Balhae after a 25-day siege in 926. After defeating Balhae, the Khitans established a puppet state founded by its new Khitan rulers, the Dongdan Kingdom, which was annexed by Liao in 936. Balhae refugees forced migration by the Liao Empire. About 470,000 refugees were moved to the Khitan proper and the Liaodong area, some Balhae aristocrats were forced to move to Liaoyang, but Balhae's eastern territory remained politically independent. Finally Balhae people integrated into different ethnicities such as Khitan, Jurchen, and Goryeo.

Aftermath and legacy

After the fall of Balhae and its last king in 926, Khitans placed Dongdan in this area, but was practically direct governance. Balhae people are widely distributed in Liao empire, some Balhae aristocrats were married with the Khitan royal family, the ruins of Balhae were discovered in the ancient city of Bars-Hot in Mongolia, the remains of Balhae culture were also found in the Nanai people distributed in the estuary of the Amur River. Restoration movements by displaced Balhae people established Later Balhae, which was later renamed to Jeongan. Though Balhae was lost, a great portion of the royalty and aristocracy fled to Goryeo, a newly formed Korean kingdom that was, founded by Goguryeo descendants. There, they were given places to live along with positions in accordance to their status before the fall. The Goryeosa notes the existence of additional mass emigrations of the dispersed Balhae people before the fall of Jeongan.

Dae Gwang-hyeon, the last crown prince, and much of the ruling class of Balhae sought refuge in Goryeo, where they were granted land and the crown prince included in the royal household by Wang Geon, Koreans believe thus unifying the two successor nations of Goguryeo. The Goryeo scholar Choi Seungno referred these events in the Shimu 28 (Korean: 시무 28조, Chinese: 時務二十八條).

Goryeosa records the arrival of tens of thousands of Balhae households to Goryeo, led by a general escaping from the Khitans in 925, one year before the final collapse of the kingdom. The rest of the Balhae people were assimilated into the Khitan polity as well as the Jurchens who would revolt against the Khitans later in the century. Some descendants of the Balhae royalty in Goryeo changed their family name to Tae (태, 太) while Crown Prince Dae Gwang-hyeon was given the family name Wang (왕, 王), the royal family name of the Goryeo dynasty. Balhae was the last state in Korean history to hold any significant territory in Manchuria, although later Korean dynasties would continue to regard themselves as successors of Goguryeo and Balhae.

The Khitans themselves eventually succumbed to the Jurchen people, the descendants of the Mohe, who founded the Jin dynasty. Jurchen proclamations emphasized the common descent of the Balhae and Jurchens from the seven Wuji(勿吉) tribes, and proclaimed "Jurchen and Balhae are from the same family". The fourth, fifth and seventh emperors of Jin were mothered by Balhae consorts. The 13th century census of Northern China by the Mongols distinguished Balhae people who belonged to khitan from other ethnic groups such as Goryeo, Khitan and Jurchen.

Government and culture

See also: List of Balhae monarchs| Monarchs of Korea |

| Balhae |

|---|

|

Balhae's population was composed of former Goguryeo peoples and Tungusic Mohe people in Manchuria. Because of the lack of developed agriculture also, most of the kingdom’s population was semi-nomadic. According to Lee ki-baik, the Mohe made up the working class which served the Goguryeo ruling class. Mohe people dominated common society, their influence was mainly restricted to providing labor. Nevertheless, there were instances of Mohe and other indigenous populations moving upward into the Balhae elite, however few, such as the followers of Geolsa Biu, who supported the establishment of Balhae, were awarded to the title of "Suryeong", or "chief", which is derived from Goguryeo language, people from different ethnicities play a part in the ruling elite. Another view is that Goguryeo descendants did not have political dominance, and the ruling system was open to all peoples equally. Its ruling structure was based on the military leader-priestly management structure of the Mohe tribes and also partly adapted elements from the Chinese system. After the 8th century, Balhae became more centralized, and power was consolidated around the king and the royal famiily.

After its founding, Balhae actively imported the culture and political system of the Tang dynasty and the Chinese reciprocated through an account of Balhae describing it as the "flourishing land of the East (海東盛国)." The bureaucracy of Balhae was modeled after the Three Departments and Six Ministries and used Chinese characters to write their native language for administrative purposes. Balhae's aristocrats and nobility traveled to the Tang capital of Chang'an on a regular basis as ambassadors and students, many of whom went on to pass the Imperial examinations. Unlike Tang government, the Balhae "taenaesang" or the "great minister of the court" was superior to the other two chancelleries (the left and the right) and its system of five capitals originates from Goguryeo's administrative structure.

The class system of Balhae society is controversial, some studies suggest there was stratified into a rigid class system similar to other Korean kingdoms. Elites tended to belong to large extended aristocratic family lines designated by surnames. The commoners in comparison had no surnames at all, and upward social mobility was virtually impossible as class and status were codified into a caste system. Other studies have shown there was a clan system but no clear division of classes existed where the position of the clan leader depended on the strength of the clan. A clan leader could become any member of the clan if he had sufficient authority. There were also religiously privileged shaman clans. The main society of the kingdom was personally free and consisted of clans.

Balhae had five capitals, fifteen provinces, and sixty-three counties. Archaeologists studying the layout of Balhae's cities have concluded that they shared features common with cities in Goguryeo, indicating that Balhae had retained cultural similarities with Goguryeo. However cities of the kingdom differed very strongly from the region, the capital of Sanggyong was organized in the way of Tang's capital of Chang'an. Residential sectors were laid out on either side of the palace surrounded by a rectangular wall, the port of An [ru] built with the use of Japanese fortification techniques and with prevailing Japanese culture.

Language and script

Some studies have shown the main language of the court of Balhae was a Tungusic language, and was an ancestral language of the Jurchen language, while Goguryeo language was also widely used. For example, Gadokbu (Korean: 가독부; Hanja: 可毒夫), the word for king that commoners used, is related with the words kadalambi (management) of the Manchu language and kadokuotto of the Nanai language. Linguistic analysis of Koreanic, Khitan, Jurchen and Manchu languages indicate the Balhae elite spoke a Koreanic language, and this Koreanic language had a lasting impact on Khitan, Jurchen and Manchu languages. Shoku Nihongi implies that the Balhae language and Silla language were mutually intelligible: a student sent from Silla to Japan for an interpreter training in the Japanese language assisted a diplomatic envoy from Balhae in communicating during the Japanese court audience.

Evidence of Balhae script comes from the remains of roof tiles used in Balhae architecture, where 370 letters were found. 135 of the letters were found to be Chinese characters. However, 151 of the letters were unidentifiable as any known script. Korean scholars believe these unidentifiable letters are part of a unique Balhae script like the Idu script of Silla. On the other hand, Chinese scholars dismissed them as miswritten Chinese characters.

Economy and trade

The place where Balhae existed now has a cold climate. Although it was mild at the time, it was a big boost to the development of the kingdom. Agriculture, livestock industry and others are also popular, especially fishery has been developed. It seems that whaling has been done as often as there are processed whales in the tribute to Tang.

Fur from Balhae, textile products and gold and mercury from Japan were exported, it seems that good dealings were made. At that time, among the aristocrats in Japan, the fur of the 貂 (Team / Itachi family member) was prized, so the import from Balhae was greatly welcomed.

Politicization

Main article: Balhae controversies See also: Northeast Project of the Chinese Academy of Social SciencesThe historic position of the Balhae is controversial between Korean and Chinese historians. Due to its origins as the successor state of Goguryeo, Korean scholars consider Balhae as part of the North–South States Period of Korean history, while Chinese scholars argue Balhae is a part of Chinese history. However, historians in Japan and Russia generally believe that Balhae is an independent state established by Mohe people, and with a significant minority of Goguryeo peoples.According to research data of Russia, estimates of the ethnic composition ratio of the residents of Balhae are 62% of people, 19% of Goguryeo, 7% of Mongolians (Mongolic speaking people such as Khitan people), 5% of Nivkh people, 3% of Japanese, 3% paleo Asians, 1% Silla people.

Media

Balhae features in the Korean film Shadowless Sword, about the last prince of Balhae, and Korean TV drama Dae Jo Yeong, which aired from September 16, 2006 to December 23, 2007, about its founder.

See also

- Ancient Tombs at Longtou Mountain

- History of Korea

- History of Manchuria

- List of Korea-related topics

- List of Provinces of Balhae

- List of rulers of Balhae

References

Note

Citations

- "渤海の遼東地域の領有問題をめぐって : 拂涅・越 喜・鉄利等靺鞨の故地と関連して" (PDF). Kyushu University Institutional Repository. 2003.

- 동북아역사재단 편 (Northeast Asian History Foundation) (2007). 새롭게 본 발해사. 동북아역사재단. p. 62. ISBN 978-89-6187-003-0.

- Kradin Nikolai Nikolaevich (2018). "Динамика урбанизационных процессов в средневековых государствах Дальнего Востока" ["Dynamics of urbanization processes in the medieval states of the Far East"]. Siberian historical research. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- Stoyakin Maxim Aleksandrovich (2012). "Культовая архитектура Бохайского времени в северной части Кореского Полуострова" ["Religious cult architecture of the Bohai time in the northern part of the Korean Peninsula"]. BUDDIST RELIGIOUS ARCHITECTURE OF PARHAE (BOHAI) LOCATED IN NORHERN PART OF KOREAN PENINSULA (in Russian). Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- 古畑徹 (2017). 渤海国とは何か 歴史文化ライブラリー (in Japanese). 吉川弘文館. ISBN 978-4642058582.

- "Appendix" (PDF). Tim. 18 January 2015. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- 京大日本史辞典編纂会 (2007). 【渤海】7世紀末から10世紀前半にかけて、中国東北地方にあったツングース系民族の国家。高句麗の同族である靺鞨から出た大祚栄により建国された (in Japanese). 日本史事典. ISBN 978-4010353134.

- Walker, Hugh Dyson (2012), East Asia: A New History, Bloomington, IN: AuthorHouse, p. 177

- Seth, Michael J. (2016), A Concise History of Korea: From Antiquity to the Present, Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, p. 71

- Kim, Djun Kil Kim (2014), The History of Korea, Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, p. 54

- ^ Michael Dillon (1 December 2016). Encyclopedia of Chinese History. Taylor & Francis. p. 95. ISBN 978-1-317-81715-4.

- 杨军 (2007). 渤海国民族构成与分布研究 (in Chinese). Jilin: 吉林人民出版社. ISBN 978-7206055102.

- Gelman Evgenia Ivanovna (2006). "Центр и периферия северо-восточной части государства Бохай" ["Center and periphery of northeastern part of Bohai state"]. Story. Historical Sciences (in Russian). Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- Michael J. Seth (21 January 2016). A Concise History of Korea: From Antiquity to the Present. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. pp. 72–73. ISBN 978-1-4422-3518-2.

- "「渤海と古代の日本」" (PDF). 2010 年度第 6 回日本海学講座. 酒寄 雅志.

- ^ Baxter-Sagart.

- ^ Jinwung Kim (2012). A History of Korea: From "Land of the Morning Calm" to States in Conflict. Indiana University Press. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-253-00024-8.

- (Shoku Nihongi) 養老4年(720年)正月23日, 遣渡嶋津輕津司従七位上諸君鞍男等六人於靺鞨国, 観其風俗

- 龍範, 李 (1976). 古代의 滿洲關係 (in Korean). 한국일보사.

- 和田淸, (1954). 渤海國地理考 (in Japanese). 東洋文庫『東亞史硏究』滿洲篇. p. 『東洋學報』36卷 4號.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - 崔致遠. 謝不許北國居上表.

- ^ Vovin, Alexander. Why Manchu and Jurchen Look so Un-Tungusic ?

- Crossley 1997, p. 18.

- "История государства Бохай" (in Russian).

- 9 Balhae and Japan Archived 2015-06-26 at the Wayback Machine Northeast Asian History Foundation

- Ŕ̿ϹŮ. "야청도의성(夜聽도衣聲)" (in Korean). Seelotus.com. Retrieved 2012-09-12.

- ^ Lee Ki-baik. "The Society and Culture of Parhae." The New History of Korea, page 88-89. Harvard University Press, 1984.

- ^ History of Liao.

- 浜田耕策 (November 2000). 渤海国興亡史 (in Japanese). 吉川弘文館. p. 215. ISBN 9784642055062. 歴史文化ライブラリー.

- Dyakova Olga Vasilyevna (2012). "К ПРОБЛЕМЕ ВЫДЕЛЕНИЯ В ПРИМОРЬЕ ПАМЯТНИКОВ ГОСУДАРСТВА ДУНДАНЬ И ИМПЕРИИ ЛЯО" ["TO THE PROBLEM OF IDENTIFYING IN PRIMORYE MONUMENTS OF THE STATE OF DUNDAN AND THE LIAO EMPIRE"]. Bulletin of the Far Eastern Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- Liang Yuduo (2010). "渤海遗民的流向" ["The flow of Balhae refugees"]. Institute of History, Heilongjiang Academy of Social Sciences (in Chinese). Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- V. V. Svinin; M. Amgalan; S. bat-Erdene; A. V. Gorbunov; J. jargalsaikhan; etc. (1991). "Киданьская керамика из раскопок городища Хаар-Бухийн-балгас (Монголия)" ["Khitan ceramics from the excavations of the settlement har-Bujin-bulgas (Mongolia)"]. Problems of archeology and Ethnography of Siberia and the Far East (in Russian). 3: 31-33.

- "Forgotten people of Balhae". youtube.

- Kim, Jinwung (2012). A History of Korea: From "Land of the Morning Calm" to States in Conflict. Indiana University Press. pp. 87–88. ISBN 978-0253000248. Retrieved 27 August 2017.

- 이상각 (2014). 고려사 - 열정과 자존의 오백년 (in Korean). 들녘. ISBN 9791159250248. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- "(2) 건국―호족들과의 제휴". 우리역사넷 (in Korean). National Institute of Korean History. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- Lee, Ki-Baik (1984). A New History of Korea. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 103. ISBN 978-0674615762. "When Parhae perished at the hands of the Khitan around this same time, much of its ruling class, who were of Koguryŏ descent, fled to Koryŏ. Wang Kŏn warmly welcomed them and generously gave them land. Along with bestowing the name Wang Kye ("Successor of the Royal Wang") on the Parhae crown prince, Tae Kwang-hyŏn, Wang Kŏn entered his name in the royal household register, thus clearly conveying the idea that they belonged to the same lineage, and also had rituals performed in honor of his progenitor. Thus Koryŏ achieved a true national unification that embraced not only the Later Three Kingdoms but even survivors of Koguryŏ lineage from the Parhae kingdom."

- Hong Won-tak. "Liao and Jin: After Khitan and Xianbei in West Manchuria, Jurchen in Eastern Manchuria appeared" East Asian History: Distortion and Correcting, page 80-110. Seoul: Gudara, 2012.

- Vasyutin Sergey Aleksandrovich (2015). "Традиционные И Инновационные Механизмы Управления В Кочевых Обществах Центральной Азии VI XIII Вв. Часть II" ["Traditional and innovative mechanisms of governance in the nomadic societies of Central Asia VI XIII centuries. Part II "]. Bulletin of Kemerovo State University. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- North Korea: A Country Study by Robert l. Worden

- Polutov Andrey Vadimovich (2014). "Государственный аппарат королевства Бохай" ["State apparatus of the kingdom of Bohai"]. Siberian historical research. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- ^ Alexander lvliev (2007). "Balhae studies in Russia". Northeast asian history foundation. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- "渤海/海東の盛国" (in Japanese).

- Injae, Lee; Miller, Owen; Jinhoon, Park; Hyun-Hae, Yi (2014-12-15). Korean History in Maps. Cambridge University Press. pp. 64–65. ISBN 9781107098466. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- ^ Crossley 1997, p. 19.

- "North Korea - Silla". Countrystudies.us. Retrieved 2012-09-15.

- Kim Alexander Alekseevich (2013). "К ВОПРОСУ О ПОЛИТИЧЕСКОЙ СИТУАЦИИ В БОХАЕ В 720-Е ГГ" ["On the issue of the political situation in Bohai in the 720s "]. BHumanitarian research in Eastern Siberia and the Far East. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- Ogata, Noboru. "Shangjing Longquanfu, the Capital of the Bohai (Parhae) State". Kyoto University. January 12, 2007. Retrieved November 10, 2011.

- Ogata, Noboru. "A Study of the City Planning System of the Ancient Bohai State Using Satellite Photos (Summary)". Jinbun Chiri. Vol.52, No.2. 2000. pp.129 - 148. Retrieved November 10, 2011.

- Kradin Nikolai Nikolaevich (2018). "Динамика Урбанизационных Процессов В Средневековых Государствах Дальнего Востока" ["Dynamics of urbanization processes in medieval states of the Far east"]. Siberian historical research. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- Kradin Nikolai Nikolaevich (2014). "ЭПИГРАФИЧЕСКИЕ МАТЕРИАЛЫ БОХАЯ И БОХАЙСКОГО ВРЕМЕНИ ИЗ ПРИМОРЬЯ" ["EPIGRAPHIC MATERIALS OF BOHAI AND BOHAI TIME FROM PRIMORYE"]. ARCHEOLOGY, ETHNOGRAPHY AND CULTURE (in Russian). Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- 赤羽目匡由 (November 2011). 渤海と古代の日本 (in Japanese). 吉川弘文館. p. 47. ISBN 9784642081504. 渤海王国の政治と社会.

- 朱国忱・魏国忠 (1996). 渤海史. 東方書店. p. 248. ISBN 978-4497954589.

- Vovin, Alexander (2017), "Koreanic loanwords in Khitan and their importance in the decipherment of the latter", Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae, 70: 207–215

- ^ Han, Giu-cheol (2008), "The Study of the Ethnic Composition of Palhae State", The Journal of Humanities Research Institute, Kyungsung University: 143–174

- ^ Bohai had a unique character.

- "唐代渤海国文字瓦" ["Tang Dynasty Balhae character tile"]. Newspaper of Heilongjiang (in Chinese).

- "Parhae's Maritime Routes to Japan in the Eighth Century" (PDF).

- "日本にも朝貢していた渤海国ってどんな国? 唐や新羅に挟まれ、友好を求めて彼らは海を渡ってきた" ["What is Balhae that was talking to Japan as well? They were caught between Tang and Silla, they came across the ocean in search of friendship"]. BUSHOO!JAPAN(武将ジャパン) (in Japanese). 2017. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- 姜成山 2014 harvnb error: no target: CITEREF姜成山2014 (help)、p4

- 酒寄雅志 (March 2001). 渤海と古代の日本. 校倉書房. p. 16. ISBN 978-4751731703. 和書.

- "Государство Бохай (698-926 гг.)" (in Russian).

- 船木勝馬; 鳥山喜一 (1968). 渤海史上の諸問題 (in Japanese). p. 352.

- Ernst Vladimirovich Shavkunov (1968). Государство Бохай и памятники его культуры в Приморье. АН СССР, Сиб. отд-ние, Дальневосточный филиал им. p. 152.

Bibliography

- Mark Byington (October 7–8, 2004). "A Matter of Territorial Security: Chinese Historiographical Treatment of Koguryo in the Twentieth Century". International Conference on Nationalism and Textbooks in Asia and Europe, Seoul, The Academy of Korean Studies.

{{cite conference}}: Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help) - 孫玉良 (1992). 渤海史料全編. 吉林文史出版社 ISBN 978-7-80528-597-9

- Crossley, Pamela Kyle (1997), The Manchus, Blackwell Publishing

- Mote, F.W. (1999), Imperial China, 900-1800, Harvard University Press, pp. 49, 61–62, ISBN 978-0-674-01212-7

- Pozzi, Alessandra; Janhunen, Juha Antero; Weiers, Michael, eds. (2006). Tumen Jalafun Jecen Aku: Manchu Studies in Honour of Giovanni Stary. Vol. Volume 20 of Tunguso Sibirica. Contributor Giovanni Stary. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3447053785. Retrieved 1 April 2013.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help)

External links

- Britannica Concise Encyclopedia

- Columbia Encyclopedia

- U.S. Library of Congress: Country Studies

- Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Stearns, Peter N. (ed.). Encyclopedia of World History (6th ed.). The Houghton Mifflin Company/Bartleby.com.

the state of Parhae (or Bohai in Chinese)

- Template:Ko icon Han's Palhae of Korea 한규철의 발해사 연구실