| Revision as of 11:20, 4 June 2019 editStefka Bulgaria (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users7,025 edits Yes, we know the MEK didn't claim or deny responsibility, but here are others that did claim responsibility← Previous edit | Revision as of 11:26, 4 June 2019 edit undoStefka Bulgaria (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users7,025 edits →Immediate aftermathNext edit → | ||

| Line 43: | Line 43: | ||

| ==Immediate aftermath== | ==Immediate aftermath== | ||

| According to a ] dispatch in the ] on June 30, 1981, "the authorities initially blamed the 'Great Satan' (the US)." ] noted that the Islamic Republic "also suspected 'SAVAK survivors and the Iraqi regime." According to ], the Nationalist Equality Party claimed credit for the attack. The pro-Soviet Tudeh part was also suspected. According to ] "a note had been found saying the Forghan group had staged the attack". Within days, the regime changed story and blamed the MEK,<ref>{{cite book|title=Mujahedin-E Khalq (MEK) Shackled by a Twisted History|author= Lincoln P. Bloomfield Jr. |year=2013|publisher=University of Baltimore College of Public Affairs|isbn=978-0615783840|pages=23-30}}</ref> and, according to BBC journalist ], the MEK were "generally perceived as the culprits" for the bombing in Iran.<ref>Moin, Baqer, ''Khomeini'', Thomas Dunne Books (2001), p. 241</ref> The MEK never publicly confirmed or denied any responsibility for the deed, but stated the attack was ‘a natural and necessary reaction to the regime's atrocities.’ The Islamic Republic identified the bomber as a young student <ref name="time">{{Citation|url=http://content.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,954849,00.html| title=Enemies of the Clergy|newspaper=Time | date=20 July 1981}}</ref> and MEK operative by the name of ], who had secured a job in the building disguised as a sound engineer.<ref> {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090628075550/http://www.shahsawandi.com/index.php?option=com_zoom&Itemid=39&page=view&catid=8&PageNo=1&key=16&hit=1 |date=2009-06-28 }}</ref> | |||

| == Iranian judicial proceedings, views and commemoration == | == Iranian judicial proceedings, views and commemoration == | ||

Revision as of 11:26, 4 June 2019

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| Hafte Tir bombing | |

|---|---|

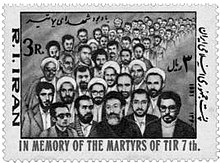

Martyrs of 7th Tir on stamp Martyrs of 7th Tir on stamp | |

| Location | Tehran, Iran |

| Coordinates | 31°15′17″N 29°59′37″E / 31.254825°N 29.993677°E / 31.254825; 29.993677 |

| Date | 28 June 1981 20:20 local time (UTC+3) |

| Target | IRP leaders |

| Attack type | Suicide bombing |

| Deaths | 73 |

On 28 June 1981 (7 Tir 1360 (Hafte Tir – هفت تیر) in the Iranian calendar), a powerful bomb went off at the headquarters of the Iran Islamic Republic Party (IRP) in Tehran, while a meeting of party leaders was in progress. Seventy-three leading officials of the Islamic Republic were killed, including Chief Justice Ayatollah Mohammad Beheshti (who was the second-most powerful figure in the revolution after Ayatollah Khomeini at the time). The Islamic Republic of Iran first blamed SAVAK and the Iraqi regime. Two days later, the People's Mujahedin of Iran was accused by Ruhollah Khomeini. According to The Times, the Nationalist Equality Party claimed credit for the attack, and that "a note had been found saying the Forghan group had staged the attack."

Bombing

On 28 June 1981 the Hafte tir bombing occurred killing the chief justice and party secretary Ayatollah Mohammad Beheshti, four cabinet ministers (Health, transport, telecommunications and energy ministers), twenty-seven members of the Majlis, including Mohammad Montazeri, and several other government officials.

Immediate aftermath

According to a Reuters dispatch in the New York Times on June 30, 1981, "the authorities initially blamed the 'Great Satan' (the US)." Ervand Abrahamian noted that the Islamic Republic "also suspected 'SAVAK survivors and the Iraqi regime." According to The Times, the Nationalist Equality Party claimed credit for the attack. The pro-Soviet Tudeh part was also suspected. According to The Times "a note had been found saying the Forghan group had staged the attack". Within days, the regime changed story and blamed the MEK, and, according to BBC journalist Baqer Moin, the MEK were "generally perceived as the culprits" for the bombing in Iran. The MEK never publicly confirmed or denied any responsibility for the deed, but stated the attack was ‘a natural and necessary reaction to the regime's atrocities.’ The Islamic Republic identified the bomber as a young student and MEK operative by the name of Mohammad Reza Kolahi, who had secured a job in the building disguised as a sound engineer.

Iranian judicial proceedings, views and commemoration

A few years later, a Kermanshah tribunal executed four "Iraqi agents" for the incident. Another tribunal in Tehran executed Mehdi Tafari for the same incident. In 1985, the head of military intelligence informed the press that this had been the work of royalist army officers.Iran's security forces blamed the United States (referring to it as the Great Satan) and "internal mercenaries". Assassinations of "leading officials and active supporters of the regime by the Mujahedin were to continue for the next year or two," though they failed to overthrow the government.

According to Tasnim, it is not possible that MEK to be fully responsible for the incident, and the bomb had been transmitted to Iran or built by military technicians in the country, with the help of Western and Israeli spy services. In other words, the United States and Israel, with the sophisticated technology of that day, designed the bomb and plan of operation then presented the bomb and plan to MEK for operating.

To commemorate the event several public places in Iran including major squares in Tehran and other cities are named “Hafte Tir”.

Analysis

According to Ervand Abrahamian, "whatever the truth, the Islamic Republic used the incident to wage war on the Left opposition in general and the Mojahedin in particular."

According to Kenneth Katzman, "there has been much speculation among academics and observers that these bombings may have actually been planned by senior IRP leaders, to rid themselves of rivals within the IRP."

The 2006 U.S. department of state Country report says that "In 1981, the MEK detonated bombs in the head office of the Islamic Republic Party and the Premier's office, killing some 70 high-ranking Iranian officials."

Mohammad-Reza Kolahi murder in 2015

Mohammad-Reza Kolahi, accused of being involved in the bombing, was murdered in 2015. Kolahi was living in the Netherlands as refugee, was married to an Afghan woman and had a 17-year-old son. Iran denied it was involved in the murder.

See also

References

- "33 HIGH IRANIAN OFFICIALS DIE IN BOMBIMG AT PARTY MEETING; CHIEF JUDGE IS AMONG VICTIMS", NY Times

- ^ "Religion in Iran – Terror and Repression", Atheism (FAQ), About

- ^ "Eighties club", The Daily News, June 1981

- ^ "Iran ABC News broadcast", The Vanderbilt Television News Archive

- Colgan, Jeff. Petro-Aggression: When Oil Causes War. Cambridge University Press 2013. p. 167. ISBN 9781107029675.

- S. Ismael, Jacqueline; Perry, Glenn; Y. Ismael, Tareq. Government and Politics of the Contemporary Middle East: Continuity and change. Routledge (2015). p. 181. ISBN 9781317662839.

- Newton, Michael. Famous Assassinations in World History: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO (2014). p. 27. ISBN 9781610692861.

- Pedde, Nicola. "ROLE AND EVOLUTION OF THE MOJAHEDIN E-KA". ojs.uniroma1.

- McGreal, Chris. "Q&A: what is the MEK and why did the US call it a terrorist organisation?". theguardian. Retrieved 21 September 2012.

- Goulka, Jeremiah; Larson, Judith; Wilke, Elizabeth; Hansell, Lydia. "The MEK in Iraq (2009)" (PDF). rand.

- ^ "Enemies of the Clergy", Time, 20 July 1981

- Lincoln P. Bloomfield Jr. (2013). Mujahedin-E Khalq (MEK) Shackled by a Twisted History. University of Baltimore College of Public Affairs. pp. 23–30. ISBN 978-0615783840.

- Lincoln P. Bloomfield Jr. (2013). Mujahedin-E Khalq (MEK) Shackled by a Twisted History. University of Baltimore College of Public Affairs. pp. 23–30. ISBN 978-0615783840.

- Moin, Baqer, Khomeini, Thomas Dunne Books (2001), p. 241

- (Persian website) Archived 2009-06-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Lincoln P. Bloomfield Jr. (2013). Mujahedin-E Khalq (MEK) Shackled by a Twisted History. University of Baltimore College of Public Affairs. p. 27. ISBN 978-0615783840.

- "33 HIGH IRANIAN OFFICIALS DIE IN BOMBIMG AT PARTY MEETING; CHIEF JUDGE IS AMONG VICTIMS", NY Times

- Abrahamian, Ervand (1989). Radical Islam: The Iranian Mojahedin. I.B. Tauris. pp. 219–220. ISBN 978-1-85043-077-3.

- Moin, Baqer, Khomeini, Thomas Dunne Books, (2001), p.243

- "ابهاماتی از حادثه هفت تیر که هرگز پاسخ داده نشد!". tasnimnews. Retrieved 29 June 2017.

- Google Maps

- Abrahamian, Ervand (1989). Radical Islam: The Iranian Mojahedin. I.B. Tauris. pp. 219–220. ISBN 978-1-85043-077-3.

- Kenneth Katzman (2001). "Iran: The People's Mojahedin Organization of Iran". In Albert V. Benliot (ed.). Iran: Outlaw, Outcast, Or Normal Country?. Nova Publishers. p. 101. ISBN 978-1-56072-954-9.

- "Background Information on Designated Foreign Terrorist Organizations". www.state.gov. Retrieved 10 December 2018.

- ^ "The story behind Iran's 'murder plot' in Denmark", BBC

- ^ "Another Twist In Mysterious Murder Of 1981 Tehran Bombing Suspect", Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, 30 May 2018, retrieved 1 June 2018

- "Death of an electrician: how luck run out for dissident who fled Iran in 1981", The Guardian, Jan. 14th 2019

- 1981 crimes in Iran

- 1981 in politics

- 20th century in Tehran

- Attacks on buildings and structures in Iran

- Conflicts involving the People's Mujahedin of Iran

- Crime in Tehran

- Explosions in Iran

- History of Tehran

- History of the Islamic Republic of Iran

- Iranian timelines

- June 1981 events

- Mass murder in 1981

- Political history of Iran

- Terrorist incidents in Iran

- Terrorist incidents in Asia in 1981

- Terrorist incidents in Iran in the 1980s