| Revision as of 16:03, 23 January 2007 view sourceSengkang (talk | contribs)38,820 edits Revert to revision 102672046 dated 2007-01-23 14:57:51 by 74.112.127.139 using popups← Previous edit | Revision as of 16:06, 23 January 2007 view source 67.33.205.196 (talk) →Blooms and groupingNext edit → | ||

| Line 51: | Line 51: | ||

| ==Blooms and grouping== | ==Blooms and grouping== | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| A group of jellyfish is often called a " |

A group of jellyfish is often called a "crack." Many species of jellyfish are also capable of congregating into large ]s or "blooms" consisting of hundreds or even thousands of individuals. The formation of these blooms is a complex process that depends on ]s, ]s, temperature and oxygen content. Jellyfish will sometimes mass breed during blooms. Jellyfish population is reportedly raising major ] concerns for a possible jellyfish outbreak. | ||

| According to Claudia Mills of the ], the frequency of these blooms may be attributed to mankind's impact on marine life. She says that the breeding jellyfish may merely be taking the place of already ] creatures. Jellyfish researcher Marsh Youngbluth further clarifies that "jellyfish feed on the same kinds of prey as adult and young fishes, so if fish are removed from the equation, jellyfish are likely to move in." | According to Claudia Mills of the ], the frequency of these blooms may be attributed to mankind's impact on marine life. She says that the breeding jellyfish may merely be taking the place of already ] creatures. Jellyfish researcher Marsh Youngbluth further clarifies that "jellyfish feed on the same kinds of prey as adult and young fishes, so if fish are removed from the equation, jellyfish are likely to move in." | ||

Revision as of 16:06, 23 January 2007

For other uses, see Jellyfish (disambiguation).

| Jellyfish | |

|---|---|

| |

| Sea nettle, Chrysaora quinquecirrha | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Cnidaria |

| Class: | Scyphozoa Goette, 1887 |

| Orders | |

Jellyfish are marine invertebrates belonging to the Scyphozoan class, and in turn the phylum Cnidaria. The body of an adult jellyfish is composed of a bell-shaped, jellylike substance enclosing its internal structure, from which the creature's tentacles are suspended. Each tentacle is covered with stinging cells (cnidocytes) that can sting or kill other animals: most jellyfish use them to secure prey or as a defense mechanism. Others, such as Rhizostomae, do not have tentacles at all. To compensate for its lack of basic sensory organs and a brain, the jellyfish exploits its nervous system and rhopalia to perceive stimuli, such as light or odor, and orchestrate expedient responses. In its adult form, it is composed of 94–98% water and can be found in every ocean in the world.

Most jellyfish are passive drifters that feed on small fish and zooplankton that become caught in their tentacles. Jellyfish have an incomplete digestive system, meaning that the same orifice is used for both food intake and waste expulsion. They are made up of a layer of epidermis, gastrodermis, and a thick jellylike layer called mesoglea that separates the epidermis from the gastrodermis.

Their shape is not hydrodynamic, which makes them slow swimmers but this is little hindrance as they feed on plankton, needing only to drift slowly through the water. It is more important for them that their movements create a current where the water (which contains their food) is being forced within reach of their tentacles. They accomplish this by rhythmically opening and closing their bell-like body.

Since jellyfish do not biologically qualify as actual "fish", the term "jellyfish" is considered a misnomer by some, who instead employ the names "jellies" or "sea jellies". The name "jellyfish" is also often used to denote either Hydrozoa or the box jellyfish, Cubozoa. The class name Scyphozoa comes from the Greek word skyphos, denoting a kind of drinking cup and alluding to the cup shape of the animal.

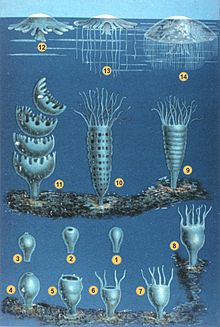

Life cycle and reproduction

Most jellyfish pass through two different body forms during their life cycle. The first is the polyp stage; in this phase, the jellyfish takes the form of either a sessile stalk which catches passing food, or a similar free-floating configuration. The polyp's mouth and tentacles are located anteriorly, facing upwards.

In the second stage, the jellyfish is known as a medusa. Medusae have a radially symmetric, umbrella-shaped body called a bell. The medusa's tentacles hang from the border of the bell.

Jellyfish are dioecious (that is, they are either male or female). In most cases, to reproduce, a male releases his sperm into the surrounding water. The sperm then swims into the mouth of the female jelly, allowing the fertilization of the ova process to begin. Moon jellies, however, use a different process: their eggs become lodged in pits on the oral arms, which form a temporary brood chamber to accommodate fertilization.

After fertilization and initial growth, a larval form, called the planula, develops from the egg. The planula larva is small and covered with cilia. It settles onto a firm surface and develops into a polyp. The polyp is cup-shaped with tentacles surrounding a single orifice, perhaps resembling a tiny sea anemone. Once the polyp begins reproducing asexually by budding, it's called a segmenting polyp, or a scyphistoma. New scyphistomae may be produced by budding or new, immature jellies called ephyra may be formed. Many jellyfish can bud off new medusae directly from the medusan stage.

Defense and feeding mechanisms

Most jellyfish have tentacles or oral arms coated with thousands of microscopic nematocysts; generally, each of these nematocyst has a "trigger" (cnidocil) paired with a capsule containing a coiled stinging filament, as well as barbs on the exterior. Upon contact, the filament will swiftly unwind, launch into the target, and inject toxins. It can then pull the victim into its mouth, if appropriate.

Although most jellyfish are not perniciously dangerous to humans, a few are highly toxic, such as Cyanea capillata. The recently discovered Carukia barnesi is also suspected of causing two deaths in Australia. Contrary to popular belief, the menacingly infamous Portuguese Man o' War (Physalia) is not actually a jellyfish, but a colony of hydrozoan polyps.

Body systems

A jellyfish can detect the touch of other animals using a nervous system called a "nerve net", which is found in its epidermis. Impulses to the nerve cells are sent from nerve rings that have collected information from the environment of the jellyfish through the rhopalial lappet, which is located around the animal's body. Jellyfish also have ocelli that cannot form images, but are sensitive to light; the jellyfish can use these to determine up from down, basing its judgement on sunlight shining on the surface of the water.

Jellyfish do not have a specialized digestive system, osmoregulatory system, central nervous system, respiratory system, or circulatory system. They are able to digest with the help of the gastrodermis that lines the gastrovascular cavity, where nutrients from their food is absorbed. They do not need a respiratory system since their skin is thin enough that oxygen can easily diffuse in and out of their bodies. Jellyfish have limited control over their movement and mostly free-float, but can use a hydrostatic skeleton that controls the water pouch in their body to actuate vertical movement.

In cell biology, ectoplasm ("outer plasma") refers to the outer regions of jelly fish. The jelly like material called (ectoplasma or plassy for short) typically contains a smaller amount of protein granules and other organic compounds than inner cytoplasm, also referred to as endoplasm.

Blooms and grouping

A group of jellyfish is often called a "crack." Many species of jellyfish are also capable of congregating into large swarms or "blooms" consisting of hundreds or even thousands of individuals. The formation of these blooms is a complex process that depends on ocean currents, nutrients, temperature and oxygen content. Jellyfish will sometimes mass breed during blooms. Jellyfish population is reportedly raising major ecological concerns for a possible jellyfish outbreak.

According to Claudia Mills of the University of Washington, the frequency of these blooms may be attributed to mankind's impact on marine life. She says that the breeding jellyfish may merely be taking the place of already overfished creatures. Jellyfish researcher Marsh Youngbluth further clarifies that "jellyfish feed on the same kinds of prey as adult and young fishes, so if fish are removed from the equation, jellyfish are likely to move in."

Increased nutrients in the water, ascribed to agricultural runoff, have also been cited as an antecedent to the recent proliferation of jellyfish numbers. Scientist Monty Graham says that "ecosystems in which there are high levels of nutrients ... provide nourishment for the small organisms on which jellyfish feed. In waters where there is eutrophication, low oxygen levels often result, favoring jellyfish as they thrive in less oxygen-rich water than fish can tolerate. The fact is that jellyfish are increasing is a symptom of something happening in the ecosystem."

By sampling sea life in a heavily fished region off the coast of Namibia, researchers have found that jellyfish have actually overtaken fish in terms of the biomass they contribute to this ocean region. The findings represent a careful quantitative analysis of what has been called a "jellyfish explosion" following intense fishing in the area in the last few decades. The findings were reported by Andrew Brierley of the University of St. Andrews and his colleagues in the July 12, 2006 issue of the journal Current Biology.

Areas seriously affected by jellyfish blooms include the northern Gulf of Mexico, where "moon jellies have formed a kind of gelatinous net that stretches from end to end across the gulf," and the Adriatic Sea. Some jellyfish have even been spotted along coastal shores.

Captivity

Jellyfish are commonly displayed in aquariums across the United States and in other countries; among the more known are the Monterey Bay Aquarium, Vancouver Aquarium, and Maui Ocean Center. Often the tank's background is blue with the animals illuminated by side lighting to produce a high contrast effect. In natural conditions, many of the jellies are so transparent that they can be almost impossible to see.

Holding jellies in captivity also presents other problems: for one, they are not adapted to closed spaces or areas with walls, which aquariums by definition have. They also depend on the natural currents of the ocean to transport them from place to place. To compensate for this, most professional exhibits feature water flow patterns. The Monterey Bay Aquarium uses a modified version of the "kreisel" (German for "spinning top") for this purpose.

Gallery of living species

- Chrysaora quinquecirrha Chrysaora quinquecirrha

- Chrysaora quinquecirrha Chrysaora quinquecirrha

- Chrysaora quinquecirrha Chrysaora quinquecirrha

-

Chrysaora quinquecirrha

Cuisine

Sliced and marinated jellyfish bells (often known as sesame jellyfish or jellyfish salad) is a common appetizer in Chinese cuisine. It is usually made using sesame seeds, sesame oil and, occasionally, spring onion. A similar dish appears in Vietnam, with red chilli pepper added. Korean version of the dish, haepari naengchae (cold jellyfish salad), is a summertime delicacy in the country, and is usually served with sweet and sour seasoning with mustard.

Packages of jellyfish bells (Chinese: 海蜇; pinyin: hǎizhé) can be bought at Chinese grocery store in a salted and semi-desiccated form, which is usually yellow or slightly brownish in colour. The salted jellyfish does not have any fishy or unpleasant odours. It has been compared to the texture of elastic bands if dried.

Treatment of stings

When stung by a jellyfish, first aid may be in order. Though most jellyfish stings are not deadly, other stings, such as those perpetrated by the box jellyfish (Chironex fleckeri) may be fatal. Serious stings may cause anaphylaxis and eventual paralysis, and hence people stung by jellyfish must get out of the water to avoid drowning. In these serious cases, advanced professional care must be sought. This care may include administration of an antivenom and other supportive care such as required to treat the symptoms of anaphylactic shock. The most serious threat that humans face from jellyfish is the sting of the Irukandji, which has the most potent and deadly poison of any known jellyfish species.

There are three goals of first aid for uncomplicated jellyfish stings: prevent injury to rescuers, inactivate the nematocysts, and remove any tentacles stuck on the patient. To prevent injury to rescuers, barrier clothing should be worn. This protection may include anything from panty hose to wet suits to full-body sting-proof suits. Inactivating the nematocysts, or stinging cells, prevents further injection of venom into the patient.

Vinegar (3 to 10% acetic acid in water) should be applied for box jellyfish stings. However, vinegar is not recommended for Portuguese Man o' War stings. In the case of stings on or around the eyes, vinegar may be placed on a towel and dabbed around the eyes, but not in them. Salt water may also be used in case vinegar is not readily available. Fresh water should not be used if the sting occurred in salt water, as a change in pH can cause the release of additional venom. Rubbing the wound, or using alcohol, spirits, ammonia, or urine will encourage the release of venom and should be avoided.

Once deactivated, the stinging cells must be removed. This can be accomplished by picking off tentacles left on the body. First aid providers should be careful to use gloves or another readily available barrier device to prevent personal injury, and to follow standard universal precautions. After large pieces of the jellyfish are removed, shaving cream may be applied to the area and a knife edge, safety razor, or credit card may be used to take away any remaining nematocysts.

Beyond initial first aid, antihistamines such as diphenhydramine (Benadryl) may be used to control skin irritation (pruritis).

Biotechnology

In 1961, Green Fluorescent Protein was discovered in the jellyfish, Aequorea victoria, by scientists studying bioluminescence. This protein has since become one of the most useful tools in biology.

Popular culture

- The Pokémon Tentacool and Tentacruel are based on jellyfish.

- In the French animated television series Code Lyoko, there is a Xana monster known as the Scyphozoa, which looks like a robotic jellyfish.

- In Rampage: Total Destruction, there is a monster called Jill the Jellyfish.

- In the animated children's show SpongeBob SquarePants, jellyfish are frequently occurring creatures portrayed as the underwater equivalent of bees. "Jellyfishing" is a popular sport in the show, similar to butterfly catching.

- A scene in the animated children's film, Finding Nemo, entails the main characters Marlin and Dory swimming their way through a bloom of jellyfish.

- In the animated movie, Shark Tale, the characters Ernie and Bernie are a species of electric jellyfish.

- On the web, Jellyfish.com uses the humble jellyfish as its mascot.

See also

- Sea nettle

- Irukandji jellyfish (the most deadly jellyfish known to man)

- Moon jelly

- Phacellophora camtschatica

- Cubozoa (the box jellyfish)

- Physconect siphonophore

- Cassiopeas

- Physalia physalis, Portuguese Man O' War (not a true jellyfish)

- Cotylorrhiza tuberculata

- Rhizostoma pulmo (also known as the Rhizostoma octopus or white jellyfish)

- Pelagia noctiluca (jellyfish mainly found in British water and Mediterranean)

- Craspedacusta sowerbyi, freshwater "jellyfish" (not a true jellyfish)

- Lion's mane jellyfish, with the longest known tentacles (over 100 feet)

Footnotes

- ^ Fenner P, Williamson J, Burnett J, Rifkin J (1993). "First aid treatment of jellyfish stings in Australia. Response to a newly differentiated species". Med J Aust. 158 (7): 498–501. PMID 8469205.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Currie B, Ho S, Alderslade P (1993). "Box-jellyfish, Coca-Cola and old wine". Med J Aust. 158 (12): 868. PMID 8100984.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Yoshimoto C (2006). "Jellyfish species distinction has treatment implications". Am Fam Physician. 73 (3): 391. PMID 16477882.

- ^ Hartwick R, Callanan V, Williamson J (1980). "Disarming the box-jellyfish: nematocyst inhibition in Chironex fleckeri". Med J Aust. 1 (1): 15–20. PMID 6102347.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Perkins R, Morgan S (2004). "Poisoning, envenomation, and trauma from marine creatures". Am Fam Physician. 69 (4): 885–90. PMID 14989575.

- Pieribone, V. and D.F. Gruber (2006). Aglow in the Dark: The Revolutionary Science of Biofluorescence. Harvard University Press. pp. 288p.

| This article does not cite any sources. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Jellyfish" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (August 2006) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

External links

- Sea Science: Jellyfish

- Cotylorhiza tuberculata

- Treatment of Coelenterate and Jellyfish Envenomations

- British Marine Life Study Society - Jellyfish Page

- Jellyfish - Curious creatures of the sea

- Videos of Jellyfish

- Jellyfish Invasion Video

Template:Link FA Template:Link FA

Categories: