| Revision as of 06:21, 18 September 2021 editIraniangal777 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users1,908 editsNo edit summaryTag: Visual edit← Previous edit | Revision as of 06:23, 18 September 2021 edit undoIraniangal777 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users1,908 editsNo edit summaryTag: Visual editNext edit → | ||

| Line 33: | Line 33: | ||

| ]]] | ]]] | ||

| All poets in the ''Atashkadeh-ye Azar'' are mentioned by their ]s, and the book is arranged in alphabetical order.{{sfn|Matini|1987|page=183}} All verses of each poet, which were incorporated into the book, were ordered according to the rhyme in question.{{sfn|Matini|1987|page=183}} The length of text he wrote about each poet varies; for some, Azar gave detailed biographies, but for most mentioned in the book, he found two or three lines sufficient and he is equally sparing in the selections he chose from their ].{{sfn|Matini|1987|page=183}} Azar dedicated the ''Atashkadeh-ye Azar'', completed shortly before his death, to Iranian ruler ].{{sfn|de Bruijn|2011}}{{sfn|Matini|1987|page=183}} Although the work primarily deals with poets, it also contains information on the history of Iran since the Afghan invasion of 1722, a brief ] and a selection of Azar's poems.{{sfn|de Bruijn|2011}}{{sfn|Matini|1987|page=183}} | All poets in the ''Atashkadeh-ye Azar'' are mentioned by their ]s, and the book is arranged in alphabetical order.{{sfn|Matini|1987|page=183}} All verses of each poet, which were incorporated into the book, were ordered according to the rhyme in question.{{sfn|Matini|1987|page=183}} The length of text he wrote about each poet varies; for some, Azar gave detailed biographies, but for most mentioned in the book, he found two or three lines sufficient, and he is equally sparing in the selections he chose from their ].{{sfn|Matini|1987|page=183}} Azar dedicated the ''Atashkadeh-ye Azar'', completed shortly before his death, to Iranian ruler ].{{sfn|de Bruijn|2011}}{{sfn|Matini|1987|page=183}} Although the work primarily deals with poets, it also contains information on the history of Iran since the Afghan invasion of 1722, a brief ] and a selection of Azar's poems.{{sfn|de Bruijn|2011}}{{sfn|Matini|1987|page=183}} | ||

| The prose of the ''Atashkadeh-ye Azar'', although displaying certain weaknesses common to Persian literature of the 18th century, is mostly straightforward and articulate.{{sfn|Matini|1987|page=183}} The elaborate introduction to the account of contemporaneous poets incorporates several well-written passages of poetic prose.{{sfn|Matini|1987|page=183}} For the passages in which contemporaneous poetic works are written, Azar's principle was apparently to provide first choice to those verses which he had heard himself directly from the poets in question; however, his claims, in his selection from earlier poets, that he had thoroughly studied the ''divans'' of those poets, is refuted through careful examination the earlier ''tazkerehs'' available to Azar.{{sfn|Matini|1987|page=183}} | The prose of the ''Atashkadeh-ye Azar'', although displaying certain weaknesses common to Persian literature of the 18th century, is mostly straightforward and articulate.{{sfn|Matini|1987|page=183}} The elaborate introduction to the account of contemporaneous poets incorporates several well-written passages of poetic prose.{{sfn|Matini|1987|page=183}} For the passages in which contemporaneous poetic works are written, Azar's principle was apparently to provide first choice to those verses which he had heard himself directly from the poets in question; however, his claims, in his selection from earlier poets, that he had thoroughly studied the ''divans'' of those poets, is refuted through careful examination the earlier ''tazkerehs'' available to Azar.{{sfn|Matini|1987|page=183}} | ||

Revision as of 06:23, 18 September 2021

18th-century Iranian poet and anthologist| Azar Bigdeli | |

|---|---|

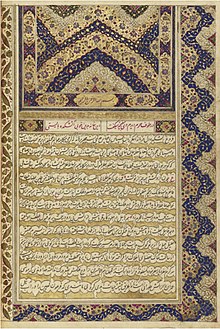

Manuscript of Azar Bigdeli's Atashkadeh-ye Azar. Copy made in Qajar Iran, dated 1824 Manuscript of Azar Bigdeli's Atashkadeh-ye Azar. Copy made in Qajar Iran, dated 1824 | |

| Born | 7 February 1722 Isfahan, Safavid Iran |

| Died | 1781 Qom, Zand Iran |

| Pen name | Azar |

| Occupation | Anthologist, poet |

| Relatives | Agha Khan Bigdeli Shamlu (father), died 1737 or 1738 Esḥāq Beg ʿUdhrī (brother), died 1771 or 1772 Wali Mohammad Khan Bigdeli (paternal uncle), died 1763 |

Hajji Lotf-Ali Beg Azar Bigdeli, better known as Azar Bigdeli (Template:Lang-fa; "Azar" was his pen name; 1722–1781), was an Iranian anthologist and poet. He is principally known for his biographical anthology, the Atashkadeh-ye Azar (Azar's Fire Temple), which he dedicated to Iranian ruler Karim Khan Zand (r. 1751–1779). Written in Persian, it is considered "the most important Persian anthology of the eighteenth century". Azar was a leading figure of the bazgasht-e adabi ("literary return") movement, which sought to return the stylistic standards of early Persian poetry.

Life

Azar's family was descended from the Bigdeli branch of the Turkoman Shamlu tribe. His ancestors and other Shamlu-tribe members moved from Syria to Iran in the 15th century (during the last few years of Timur's reign) and settled in Isfahan, where they served the rulers of Iran. Many of Azar's relatives were prominent in the late Safavid era and during the subsequent reign of Nader Shah (r. 1736–1747) as diplomats and bureaucrats.

Azar was born in Isfahan, the Safavid royal capital, during a time of chaos and instability. In 1722 (the year of his birth), the Safavid state had entered the final stages of collapse and the rebellious Afghans had reached Isfahan. Azar and his family were forced to move to Qom, where they owned property and where he lived for fourteen years. Around 1735 or 1736, his father Agha Khan Bigdeli Shamlu was appointed governor of Lar and the coastal areas of Fars Province by Nader Shah and Azar, and his family moved to Shiraz (the provincial capital of Fars). In 1737 or 1738, after the death of his father, Azar made pilgrimages to Mecca and the Shi'ite shrines in Iran and Iraq. He then moved to Mashhad, where his arrival coincided with Nader Shah's return from his successful Indian campaign. Azar subsequently enlisted in Nader's army and accompanied his troops to Mazandaran, Azerbaijan, and Persian Iraq. After Nader's death in 1747, Azar served his nephews and successors Adel Shah (r. 1747–1748) and Ebrahim Shah (r. 1748), and the Safavid pretenders Ismail III and Suleiman II before retiring to his modest manor in Qom.

When Karim Khan Zand (r. 1751–1779) ascended the throne, Azar decided to devote his time to scholarly pursuits and returned to Isfahan where he and other poets of the bazgasht-e adabi movement benefitted from the peaceful conditions under Karim Khan's rule and the support of the cities' Zand governor Mirzā ʿAbd ol-Vahhāb (died 1760), who was a patron of the arts. The city was sacked by Ali Mardan Khan Bakhtiari in 1750, and Azar reportedly lost about 7,000 of his early written verses; however, he was still a respected poet during his lifetime. In 1774 or 1775, Azar was forced to leave Isfahan again, due to misrule by Zand governor Hājji Mohammad Ranāni Esfahāni (in office; 1760–1765). He and his friend Hatef Esfahani (died 1783), who was also a native of Isfahan and a member of the bazgasht-e adabi movement, eventually ended up at Kashan where their mutual friend Sabahi Bidgoli (died 1803) had lived most of his life. The friendship of Azar, Hatef and Sabahi is attested in many of their poems in which they declare their admiration of and devotion to one another. Azar was at Kashan when the 1778 Kashan earthquake struck in which he lost his brother and his house. Thus he was forced to move once again, most likely to Qom, where he died three years later in 1781.

Literary career

Atashkadeh-ye Azar

Azar is principally known for his anthology (tazkereh), the Atashkadeh-ye Azar (Azar's Fire Temple), which he started writing in 1760/1 and is considered "the most important Persian anthology of the eighteenth century". Its chapter titles are based metaphorically on "fire". According to the Persian studies academic Jalal Matini, Azar chose to him as to underline his mission to defend Persian poetry as a member of the bazgast-e adabi movement.

The book consists of two sections, both of which Azar called a majmareh (literally, "censer"). The first majmareh is further divided into one sholeh ("flame") on the poetry of kings, princes and amirs; three aḵgars ("embers") on the poets of Iran, Central Asia (Turan) and India (Hindustan); and one forūḡ ("light") consisting of an appendix dealing with female poets. The three aḵgars are further divided in terms of geographical divisions, into five, three and three sharārehs ("sparks") respectively, each one of them starting with a brief description of the region involved. Azar's main reference for this part of the book was an anthology written by the Safavid-period poet Taqi ol-Din Kashani (died after 1607/8), known as the Kholāṣat ol-ashʿār ("The essence of the poems"). The second majmareh i.e. section consists of two partows ("beams")'. The first partow deals with the contemporaneous poets of Azar's own lifetime (some of whom were his friends), whereas the second partow consists of Azar's biography and a selection of his poetry.

All poets in the Atashkadeh-ye Azar are mentioned by their pen names, and the book is arranged in alphabetical order. All verses of each poet, which were incorporated into the book, were ordered according to the rhyme in question. The length of text he wrote about each poet varies; for some, Azar gave detailed biographies, but for most mentioned in the book, he found two or three lines sufficient, and he is equally sparing in the selections he chose from their oeuvres. Azar dedicated the Atashkadeh-ye Azar, completed shortly before his death, to Iranian ruler Karim Khan Zand. Although the work primarily deals with poets, it also contains information on the history of Iran since the Afghan invasion of 1722, a brief autobiography, and a selection of Azar's poems.

The prose of the Atashkadeh-ye Azar, although displaying certain weaknesses common to Persian literature of the 18th century, is mostly straightforward and articulate. The elaborate introduction to the account of contemporaneous poets incorporates several well-written passages of poetic prose. For the passages in which contemporaneous poetic works are written, Azar's principle was apparently to provide first choice to those verses which he had heard himself directly from the poets in question; however, his claims, in his selection from earlier poets, that he had thoroughly studied the divans of those poets, is refuted through careful examination the earlier tazkerehs available to Azar.

Azar's Atashkadeh was often copied after it was written and was lithographed in British India in 1833/4. An account of the entire work was provided in 1843 by the Anglo-Irish scholar Nathaniel Bland. Bland published the first opening section on royal poets a year later in 1844. An abridgement of the Atashkadeh was written by Azar's brother Esḥāq Beg ʿUdhrī (died 1771/2) under the name Taḏkera-ye Eshaq, which only contains Azar's poems.

The bazgasht-e adabi

Azar's teacher, Mir Sayyed Ali Moshtaq Esfahani (c. 1689–1757), began a "literary return" movement (bazgasht-e adabi) to the stylistic standards of early Persian poetry. The Atashkadeh, like much other contemporary poetry from Isfahan and Shiraz, was an example of the bazgasht-e adabi of which Azar was a leading figure. The movement rejected what was considered excessive "Indian style" (sabk-e Hendi) in Persian poetry and sought, according to the Iranologist Ehsan Yarshater, "a return to the simpler and more robust poetry of the old masters as against the effete and artificial verse into which Safavid poetry had degenerated". Due to his links with the basgasht-e adabi, Azar is very praiseworthy of authors who rejected the Indian style and sought to revive the idiom of the early poets. He is censorious of the Persian Saib Tabrizi (died 1676), one of the majors of "Indian style" Persian poetry, as well as his followers.

Azar praises his teacher, Mir Sayyed Ali Moshtaq Esfahani, in the Atashkadeh:

after he had broken the chain of verse that for years had been in the unworthy grip of poets of the past, with great effort and indescribable exertions he repaired it. Having destroyed for contemporary poets the foundation of versifying, he renewed the edifice of poetry built by the eloquent ancients.

The poetry that defined Azar was also influenced by his paternal uncle, Wali Mohammad Khan Bigdeli (died 1763).

After the disastrous earthquake 1778 Kashan earthquake, Azar (as well as Hatef and Sabahi) wrote poetry commemorating the event, in which they not only expressed their personal grief, but also sought to help the audience understand the disaster of the earhquake, as the Persian studies academic Matthew C. Smith explains, "within a meaningful historical and spriticual context and to show the path forward". These particular poems, which provide insight into the bazgasht-e adabi movement "beyond mere imitation of earlier styles", underline the engagement of the members of the movement within Iran's social sphere at the time and the relevance of their poetry to the contemporaneous audience. Azar (and Hatef) chose the tarkib-band, which is a stanzaic form often used for elegiac themes.

Other works

The Persian studies academics J. T. P. de Bruijn and Matini explain that in addition to Azar's divan (collected poems of a particular author), comprising qasidehs (panegyrics), ghazals (short lyric poems of syntactically independent couplets) and qaṭʿehs (lyric poems on a single theme), four extant masnavis (poems in rhyming couplets on any theme) have been attributed to him: Yusof o Zolaykha (fragments appear in the Atashkadeh); Masnavi-e Azar, a short love poem mirroring Suz-u godaz ("Burning and Melting"), a poem by Agha Mohammad Sadeq Tafreshi which was popular in Azar's time; Saqi-nameh ("Book of the Cup-bearer"), and Moghanni-nameh ("Book of the Singer"). Azar may have also written the Ganjinat ol-haqq ("The Treasury of Truth", a work in the style of Saadi Shirazi's Golestan) and the Daftar-e noh aseman ("The Book of the Nine Skies"), an anthology of contemporary poetry.

Notes

- Also spelled "Lutf-Ali Beg Adhar Begdili".

References

- ^ de Bruijn 2011.

- ^ Matini 1987, p. 183.

- ^ Hanaway 1989, pp. 58–60.

- Doerfer 1989, pp. 251–252.

- ^ Smith 2019, p. 179.

- ^ Smith 2019, p. 180.

- Smith 2019, pp. 180, 191.

- Smith 2019, pp. 191–192.

- Sharma 2021, p. 314.

- Parsinejad 2003, p. 21.

- Yarshater 1986, p. 966.

- Smith 2019, p. 179 (note 6).

- Smith 2019, pp. 180–181.

- Smith 2019, p. 181.

Sources

- de Bruijn, J.T.P. (2011). "Ādhar, Ḥājjī Luṭf ʿAlī Beg". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (3rd ed.). Brill Online. ISSN 1873-9830.

- Doerfer, Gerhard (1989). "BĪGDELĪ". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. IV/3: Bibliographies II–Bolbol I. London and New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 251–252. ISBN 978-0-71009-126-0.

- Hanaway, William L., Jr. (1989). "BĀZGAŠT-E ADABĪ". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. IV/1: Bāyju–Behruz. London and New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 58–60. ISBN 978-0-71009-124-6.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Matini, Jalal (1987). "ĀẔAR BĪGDELĪ". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. III/2: Awāʾel al-maqālāt–Azerbaijan IV. London and New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. p. 183. ISBN 978-0-71009-114-7.

- Parsinejad, Iraj (2003). A History of Literary Criticism in Iran, 1866–1951: Literary Criticism in the Works of Enlightened Thinkers of Iran--Akhundzadeh, Kermani, Malkom, Talebof, Maragheʼi, Kasravi, and Hedayat. Ibex Publishers, Inc. ISBN 978-1588140166.

- Sharma, Sunil (2021). "Local and Transregional Places in the Works of Safavid Men of Letters". In Melville, Charles (ed.). Safavid Persia in the Age of Empires: The Idea of Iran Vol. 10. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-0755633784.

- Smith, Matthew C. (2019). "Betrayed by Earth and Sky: Poetry of Disaster and Restoration in Eighteenth-Century Iran". Journal of Persianate Studies. 11 (2): 175–202. doi:10.1163/18747167-12341326.

- Yarshater, Ehsan (1986). "Persian Poetry in the Timurid and Safavid Periods". In Lockhart, Laurence; Jackson, Peter (eds.). The Cambridge History of Iran. Vol. 6: The Timurid and Safavid Periods. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-20094-6.