| Revision as of 07:21, 25 October 2021 editManeep111 (talk | contribs)1 editNo edit summaryTags: Manual revert Reverted← Previous edit | Revision as of 08:22, 25 October 2021 edit undoR Prazeres (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users30,692 edits Undid revision 1051726678 by Maneep111 (talk) probable vandalismTag: UndoNext edit → | ||

| Line 41: | Line 41: | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| |religion = ] (official), ] (subjects) | |religion = ] (official), ] (subjects) | ||

| |common_languages = ] (religion)<ref>{{cite journal|title=International Journal of Turkish Studies|volume=11-13|publisher=University of Wisconsin|year=2005|page=8}}</ref><br/>] (official, court, literature)<ref>Grousset, Rene, ''The Empire of the Steppes: A History of Central Asia'', (Rutgers University Press, 2002), 157; "...the Seljuk court at Konya adopted Persian as its official language."</ref><ref>Bernard Lewis, ''Istanbul and the Civilization of the Ottoman Empire'', (University of Oklahoma Press, 1963), 29; "The literature of Seljuk Anatolia was almost entirely in Persian...".</ref><br/>] (spoken)<ref>{{cite book|title=Early Mystics in Turkish Literature|author=Mehmed Fuad Koprulu|year=2006|page=207|lang=en}}</ref><br/>] (chancery)<ref>Andrew Peacock and Sara Nur Yildiz, ''The Seljuks of Anatolia: Court and Society in the Medieval Middle East'', (I.B. Tauris, 2013), 132; "''The official use of the Greek language by the Seljuk chancery is well known''".</ref> | |common_languages = ] (religion)<ref>{{cite journal|title=International Journal of Turkish Studies|volume=11-13|publisher=University of Wisconsin|year=2005|page=8}}</ref><br/>] (official, court, literature)<ref>Grousset, Rene, ''The Empire of the Steppes: A History of Central Asia'', (Rutgers University Press, 2002), 157; "...the Seljuk court at Konya adopted Persian as its official language."</ref><ref>Bernard Lewis, ''Istanbul and the Civilization of the Ottoman Empire'', (University of Oklahoma Press, 1963), 29; "The literature of Seljuk Anatolia was almost entirely in Persian...".</ref><br/>] (spoken)<ref>{{cite book|title=Early Mystics in Turkish Literature|author=Mehmed Fuad Koprulu|year=2006|page=207|lang=en}}</ref><br/>] (chancery)<ref>Andrew Peacock and Sara Nur Yildiz, ''The Seljuks of Anatolia: Court and Society in the Medieval Middle East'', (I.B. Tauris, 2013), 132; "''The official use of the Greek language by the Seljuk chancery is well known''".</ref> | ||

| |title_leader = ] | |title_leader = ] | ||

| |leader1 = ] | |leader1 = ] | ||

| Line 53: | Line 53: | ||

| {{History of Turkey}} | {{History of Turkey}} | ||

| The '''Sultanate of Rum'''{{efn|Modernly referred to as '''Anatolian Seljuk Sultanate''', '''Sultanate of Iconium''', '''Anatolian Seljuk State''' ({{lang-tr|Anadolu Selçuklu Devleti}}) or ''' |

The '''Sultanate of Rum'''{{efn|Modernly referred to as '''Anatolian Seljuk Sultanate''', '''Sultanate of Iconium''', '''Anatolian Seljuk State''' ({{lang-tr|Anadolu Selçuklu Devleti}}) or '''Seljuks of Turkey''' ({{lang-tr|Türkiye Selçukluları}})<ref>Beihammer, Alexander Daniel (2017). ''Byzantium and the Emergence of Muslim-Turkish Anatolia, ca. 1040-1130''. New York: Routledge. p. 15.</ref>}} or '''Rum Seljuk Sultanate''' ({{lang-fa|سلجوقیان روم|Saljuqiyān-e Rum|lit=Seljuks of Rome}}) was a ]<ref>Bernard Lewis, ''Istanbul and the Civilization of the Ottoman Empire'', 29; "Even when the land of Rum became politically independent, it remained a colonial extension of Turco-Persian culture which had its centers in Iran and Central Asia''","''The literature of Seljuk Anatolia was almost entirely in Persian ..."</ref><ref>"Institutionalisation of Science in the Medreses of pre-Ottoman and Ottoman Turkey", Ekmeleddin Ihsanoglu, ''Turkish Studies in the History and Philosophy of Science'', ed. Gürol Irzik, Güven Güzeldere, (Springer, 2005), 266; "Thus, in many of the cities where the Seljuks had settled, Iranian culture became dominant."</ref><ref>Andrew Peacock and Sara Nur Yildiz, ''The Seljuks of Anatolia: Court and Society in the Medieval Middle East'', (I.B. Tauris, 2013), 71-72</ref><ref>''Turko-Persia in Historical Perspective'', ed. Robert L. Canfield, (Cambridge University Press, 1991), 13.</ref> ] ruled state, established over conquered ] territories and peoples (]) of ] by the ] following their entry into Anatolia after the ] (1071). The name '']'' was a synonym for the medieval Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire and ], as it remains in modern Turkish. It derives from the Arabic name for ], {{lang|ar|الرُّومُ}} ''ar-Rūm'' via a loan from ] {{lang|grc|Ῥωμαῖοι}}, "], citizens of the Eastern Roman Empire".<ref>Alexander Kazhdan, "Rūm" ''The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium'' (Oxford University Press, 1991), vol. 3, p. 1816. | ||

| ], ''Rise of the Ottoman Empire'', Royal Asiatic Society Books, Routledge (2013), : | ], ''Rise of the Ottoman Empire'', Royal Asiatic Society Books, Routledge (2013), : | ||

| "This state too bore the name of Rûm, if not officially, then at least in everyday usage, and its princes appear in the Eastern chronicles under the name 'Seljuks of Rûm' (Ar.: ''Salâjika ar-Rûm''). A. Christian Van Gorder, ''Christianity in Persia and the Status of Non-muslims in Iran'' p. 215: "The Seljuqs called the lands of their sultanate ''Rum'' because it had been established on territory long considered 'Roman', i.e. Byzantine, by Muslim armies." | "This state too bore the name of Rûm, if not officially, then at least in everyday usage, and its princes appear in the Eastern chronicles under the name 'Seljuks of Rûm' (Ar.: ''Salâjika ar-Rûm''). A. Christian Van Gorder, ''Christianity in Persia and the Status of Non-muslims in Iran'' p. 215: "The Seljuqs called the lands of their sultanate ''Rum'' because it had been established on territory long considered 'Roman', i.e. Byzantine, by Muslim armies." | ||

Revision as of 08:22, 25 October 2021

Muslim state in central Anatolia from 1077 to 1308| Sultanate of RûmAnadolu Selçuklu Devleti سلجوقیان روم Saljūqiyān-i Rūm | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1077–1308 | |||||||||||||||||||

Double-headed eagle used by the Rum Seljuks

Double-headed eagle used by the Rum Seljuks

Lion and Sun adopted by Kaykhusraw II

Lion and Sun adopted by Kaykhusraw II

| |||||||||||||||||||

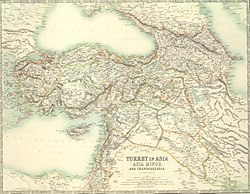

Expansion of the Sultanate c. 1100–1240 Expansion of the Sultanate c. 1100–1240 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Status | Sultanate | ||||||||||||||||||

| Capital |

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Arabic (religion) Persian (official, court, literature) Old Anatolian Turkish (spoken) Byzantine Greek (chancery) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam (official), Greek Orthodox (subjects) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Sultan | |||||||||||||||||||

| • 1077–1086 | Suleiman ibn Qutalmish | ||||||||||||||||||

| • 1220–1237 | Kayqubad I | ||||||||||||||||||

| • 1303–1308 | Mesud II | ||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||

| • Division from the Seljuk Empire | 1077 | ||||||||||||||||||

| • Battle of Köse Dağ | 1243 | ||||||||||||||||||

| • death of Mesud II | 1308 | ||||||||||||||||||

| • Karamanid conquest | 1328 | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

The Sultanate of Rum or Rum Seljuk Sultanate (Template:Lang-fa) was a Turko-Persian Sunni Muslim ruled state, established over conquered Byzantine territories and peoples (Rûm) of Anatolia by the Seljuk Turks following their entry into Anatolia after the Battle of Manzikert (1071). The name Rûm was a synonym for the medieval Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire and its peoples, as it remains in modern Turkish. It derives from the Arabic name for ancient Rome, الرُّومُ ar-Rūm via a loan from Koine Greek Ῥωμαῖοι, "Romans, citizens of the Eastern Roman Empire".

The Sultanate of Rum seceded from the Great Seljuk Empire under Suleiman ibn Qutalmish in 1077, just six years after the Byzantine provinces of central Anatolia were conquered at the Battle of Manzikert (1071). It had its capital first at İznik and then at Konya. It reached the height of its power during the late 12th and early 13th century, when it succeeded in taking key Byzantine ports on the Mediterranean and Black Sea coasts. In the east, the sultanate reached Lake Van. Trade through Anatolia from Iran and Central Asia was developed by a system of caravanserai. Especially strong trade ties with the Genoese formed during this period. The increased wealth allowed the sultanate to absorb other Turkish states that had been established following the conquest of Byzantine Anatolia: Danishmendids, House of Mengüjek, Saltukids, Artuqids.

The Seljuk sultans bore the brunt of the Crusades and eventually succumbed to the Mongol invasion at the 1243 Battle of Köse Dağ. For the remainder of the 13th century, the Seljuks acted as vassals of the Ilkhanate. Their power disintegrated during the second half of the 13th century. The last of the Seljuk vassal sultans of the Ilkhanate, Mesud II, was murdered in 1308. The dissolution of the Seljuk state left behind many small Anatolian beyliks (Turkish principalities), among them that of the Ottoman dynasty, which eventually conquered the rest and reunited Anatolia to become the Ottoman Empire.

History

Further information: Timeline of the Seljuk Sultanate of RumEstablishment

In the 1070s, after the battle of Manzikert, the Seljuk commander Suleiman ibn Qutulmish, a distant cousin of Malik-Shah I and a former contender for the throne of the Seljuk Empire, came to power in western Anatolia. In 1075, he captured the Byzantine cities of Nicaea (İznik) and Nicomedia (İzmit). Two years later, he declared himself sultan of an independent Seljuk state and established his capital at İznik.

Suleiman was killed in Antioch in 1086 by Tutush I, the Seljuk ruler of Syria, and Suleiman's son Kilij Arslan I was imprisoned. When Malik Shah died in 1092, Kilij Arslan was released and immediately established himself in his father's territories.

Crusades

| Crusades: battles in the Levant (1096–1303) | |

|---|---|

Period post-Second Crusade

Period post-Third Crusade Sixth Crusade and aftermath |

Kilij Arslan, although victorious in the People's Crusade of 1096, was defeated by soldiers of the First Crusade and driven back into south-central Anatolia, where he set up his state with capital in Konya. He defeated three Crusade contingents in the 1101 Crusade. In 1107, he ventured east and captured Mosul but died the same year fighting Malik Shah's son, Mehmed Tapar. He was the first Muslim commander against the crusades.

Meanwhile, another Rum Seljuk, Malik Shah (not to be confused with the Seljuk sultan of the same name), captured Konya. In 1116 Kilij Arslan's son, Mesud I, took the city with the help of the Danishmends.

Upon Mesud's death in 1156, the sultanate controlled nearly all of central Anatolia. Mesud's son, Kilij Arslan II, captured the remaining territories around Sivas and Malatya from the last of the Danishmends. At the Battle of Myriokephalon in 1176, Kilij Arslan II also defeated a Byzantine army led by Manuel I Komnenos. Despite a temporary occupation of Konya in 1190 by the Holy Roman Empire's forces of the Third Crusade, the sultanate was quick to recover and consolidate its power. During the last years of Kilij Arslan II's reign, the sultanate experienced a civil war with Kaykhusraw I fighting to retain control and losing to his brother Suleiman II in 1196.

Suleiman II rallied his vassal emirs and marched against Georgia, with an army of 150,000-400,000 and encamped in the Basiani valley. Tamar of Georgia quickly marshaled an army throughout her possessions and put it under command of her consort, David Soslan. Georgian troops under David Soslan made a sudden advance into Basiani and assailed the enemy’s camp in 1203 or 1204. In a pitched battle, the Seljukid forces managed to roll back several attacks of the Georgians but were eventually overwhelmed and defeated. Loss of the sultan's banner to the Georgians resulted in a panic within the Seljuk ranks. Süleymanshah himself was wounded and withdrew to Erzurum. Both the Rum Seljuk and Georgian armies suffered heavy casualties, but coordinated flanking attacks won the battle for the Georgians.

Suleiman II died in 1204 and was succeeded by his son Kilij Arslan III, whose reign was unpopular. Kaykhusraw I seized Konya in 1205 reestablishing his reign. Under his rule and those of his two successors, Kaykaus I and Kayqubad I, Seljuk power in Anatolia reached its apogee. Kaykhusraw's most important achievement was the capture of the harbour of Attalia (Antalya) on the Mediterranean coast in 1207. His son Kaykaus captured Sinop and made the Empire of Trebizond his vassal in 1214. He also subjugated Cilician Armenia but in 1218 was forced to surrender the city of Aleppo, acquired from al-Kamil. Kayqubad continued to acquire lands along the Mediterranean coast from 1221 to 1225.

In the 1220s, he sent an expeditionary force across the Black Sea to Crimea. In the east he defeated the Mengujekids and began to put pressure on the Artuqids.

Mongol conquest

Kaykhusraw II (1237–1246) began his reign by capturing the region around Diyarbakır, but in 1239 he had to face an uprising led by a popular preacher named Baba Ishak. After three years, when he had finally quelled the revolt, the Crimean foothold was lost and the state and the sultanate's army had weakened. It is in these conditions that he had to face a far more dangerous threat, that of the expanding Mongols. The forces of the Mongol Empire took Erzurum in 1242 and in 1243, the sultan was crushed by Baiju in the Battle of Köse Dağ (a mountain between the cities of Sivas and Erzincan), and the Seljuk Turks were forced to swear allegiance to the Mongols and became their vassals. The sultan himself had fled to Antalya after the 1243 battle, where he died in 1246, his death starting a period of tripartite, and then dual, rule that lasted until 1260.

The Seljuk realm was divided among Kaykhusraw's three sons. The eldest, Kaykaus II (1246–1260), assumed the rule in the area west of the river Kızılırmak. His younger brothers, Kilij Arslan IV (1248–1265) and Kayqubad II (1249–1257), were set to rule the regions east of the river under Mongol administration. In October 1256, Bayju defeated Kaykaus II near Aksaray and all of Anatolia became officially subject to Möngke Khan. In 1260 Kaykaus II fled from Konya to Crimea where he died in 1279. Kilij Arslan IV was executed in 1265, and Kaykhusraw III (1265–1284) became the nominal ruler of all of Anatolia, with the tangible power exercised either by the Mongols or the sultan's influential regents.

Disintegration

The Seljuk state had started to split into small emirates (beyliks) that increasingly distanced themselves from both Mongol and Seljuk control. In 1277, responding to a call from Anatolia, the Mamluk Sultan Baibars raided Anatolia and defeated the Mongols at the Battle of Elbistan, temporarily replacing them as the administrator of the Seljuk realm. But since the native forces who had called him to Anatolia did not manifest themselves for the defense of the land, he had to return to his home base in Egypt, and the Mongol administration was re-assumed, officially and severely. Also, the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia captured the Mediterranean coast from Selinos to Seleucia, as well as the cities of Marash and Behisni, from the Seljuk in the 1240s.

Near the end of his reign, Kaykhusraw III could claim direct sovereignty only over lands around Konya. Some of the beyliks (including the early Ottoman state) and Seljuk governors of Anatolia continued to recognize, albeit nominally, the supremacy of the sultan in Konya, delivering the khutbah in the name of the sultans in Konya in recognition of their sovereignty, and the sultans continued to call themselves Fahreddin, the Pride of Islam. When Kaykhusraw III was executed in 1284, the Seljuk dynasty suffered another blow from internal struggles which lasted until 1303 when the son of Kaykaus II, Mesud II, established himself as sultan in Kayseri. He was murdered in 1308 and his son Mesud III soon afterwards. A distant relative to the Seljuk dynasty momentarily installed himself as emir of Konya, but he was defeated and his lands conquered by the Karamanids in 1328. The sultanate's monetary sphere of influence lasted slightly longer and coins of Seljuk mint, generally considered to be of reliable value, continued to be used throughout the 14th century, once again, including by the Ottomans.

Culture and society

Further information: Seljuk architectureThe Seljuk dynasty of Rum, as successors to the Great Seljuks, based its political, religious and cultural heritage on the Perso-Islamic tradition and Greco-Roman tradition, even to the point of naming their sons with Persian names. Though of Turkic origin, Rum Seljuks patronized Persian art, architecture, and literature and used Persian as a language of administration. One of its most famous Persian writers, Rumi, took his name from the name of the state. Moreover, Byzantine influence in the Sultanate was also significant, since Byzantine Greek aristocracy remained part of the Seljuk nobility, and the native Byzantine (Rûm) peasants remained numerous in the region.

In their construction of caravanserais, madrasas and mosques, the Rum Seljuks translated the Iranian Seljuk architecture of bricks and plaster into the use of stone. Among these, the caravanserais (or hans), used as stops, trading posts and defense for caravans, and of which about a hundred structures were built during the Anatolian Seljuk period, are particularly remarkable. Along with Persian influences, which had an indisputable effect, Seljuk architecture was inspired by local Byzantine (Rûm) architects, for example the Gök Medrese (Sivas), and by Armenians. As such, Anatolian architecture represents some of the most distinctive and impressive constructions in the entire history of Islamic architecture. Later, this Anatolian architecture would be inherited by the Sultanate of India.

The largest caravanserai is the Sultan Han (built in 1229) on the road between the cities of Konya and Aksaray, in the township of Sultanhanı, covering 3,900 m (42,000 sq ft). There are two caravanserais that carry the name "Sultan Han", the other one being between Kayseri and Sivas. Furthermore, apart from Sultanhanı, five other towns across Turkey owe their names to caravanserais built there. These are Alacahan in Kangal, Durağan, Hekimhan and Kadınhanı, as well as the township of Akhan within the Denizli metropolitan area. The caravanserai of Hekimhan is unique in having, underneath the usual inscription in Arabic with information relating to the edifice, two further inscriptions in Armenian and Syriac, since it was constructed by the sultan Kayqubad I's doctor (hekim) who is thought to have been a former Christian who converted to Islam. There are other particular cases like the settlement in Kalehisar (contiguous to an ancient Hittite site) near Alaca, founded by the Seljuk commander Hüsameddin Temurlu, who had taken refuge in the region after the defeat in the Battle of Köse Dağ and had founded a township comprising a castle, a madrasa, a habitation zone and a caravanserai, which were later abandoned apparently around the 16th century. All but the caravanserai, which remains undiscovered, was explored in the 1960s by the art historian Oktay Aslanapa, and the finds as well as a number of documents attest to the existence of a vivid settlement in the site, such as a 1463 Ottoman firman which instructs the headmaster of the madrasa to lodge not in the school but in the caravanserai.

The Seljuk palaces, as well as their armies, were staffed with ghulams (plural ghilmân, Template:Lang-ar), enslaved youths taken from non-Muslim communities, mainly Greeks from former Byzantine territories. The practice of keeping ghulams may have offered a model for the later devşirme during the time of the Ottoman Empire.

Dynasty

Main articles: Anatolian Seljuks family tree and Seljuk dynasty

As regards the names of the sultans, there are variants in form and spelling depending on the preferences displayed by one source or the other, either for fidelity in transliterating the Persian variant of the Arabic script which the sultans used, or for a rendering corresponding to the modern Turkish phonology and orthography. Some sultans had two names that they chose to use alternatively in reference to their legacy. While the two palaces built by Alaeddin Keykubad I carry the names Kubadabad Palace and Keykubadiye Palace, he named his mosque in Konya as Alâeddin Mosque and the port city of Alanya he had captured as "Alaiye". Similarly, the medrese built by Kaykhusraw I in Kayseri, within the complex (külliye) dedicated to his sister Gevher Nesibe, was named Gıyasiye Medrese, and the one built by Kaykaus I in Sivas as Izzediye Medrese.

| Sultan | Reign | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Qutalmish | 1060–1064 | Contended with Alp Arslan for succession to the Imperial Seljuk throne. |

| 2. Suleiman ibn Qutulmish | 1075-1077 de facto rules Turkmen around İznik and İzmit; 1077–1086 recognised Rum Sultan by Malik I | Founder of Anatolian Seljuk Sultanate with capital in İznik |

| 3. Kilij Arslan I | 1092–1107 | First sultan in Konya |

| 4. Malik Shah | 1107–1116 | |

| 5. Masud I | 1116–1156 | |

| 6. 'Izz al-Din Kilij Arslan II | 1156–1192 | |

| 7. Giyath al-Din Kaykhusraw I | 1192–1196 | First reign |

| 8. Rukn al-Din Suleiman II | 1196–1204 | |

| 9. Kilij Arslan III | 1204–1205 | |

| Giyath al-Din Kaykhusraw I | 1205–1211 | Second reign |

| 10. 'Izz al-Din Kayka'us I | 1211–1220 | |

| 11. 'Ala al-Din Kayqubad I | 1220–1237 | |

| 12. Giyath al-Din Kaykhusraw II | 1237–1246 | After his death, sultanate split until 1260 when Kilij Arslan IV remained the sole ruler |

| 13. 'Izz al-Din Kayka'us II | 1246–1260 | |

| 14. Rukn al-Din Kilij Arslan IV | 1248–1265 | |

| 15. 'Ala al-Din Kayqubad II | 1249–1257 | |

| 16. Giyath al-Din Kaykhusraw III | 1265–1284 | |

| 17. Giyath al-Din Masud II | 1284–1296 | First reign |

| 18. 'Ala al-Din Kayqubad III | 1298–1302 | |

| Giyath al-Din Masud II | 1303–1308 | Second reign |

See also

| History of the Turkic peoples pre–14th century | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Turkic peoples

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Turkic Languages

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Turkic Mythology

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Pre-14th century

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Timeline of the Seljuk Sultanate of Rûm

- Babai Revolt

- Byzantine–Seljuk Wars

- Rûm Province, Ottoman Empire

Notes

- Modernly referred to as Anatolian Seljuk Sultanate, Sultanate of Iconium, Anatolian Seljuk State (Template:Lang-tr) or Seljuks of Turkey (Template:Lang-tr)

References

- "International Journal of Turkish Studies". 11–13. University of Wisconsin. 2005: 8.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Grousset, Rene, The Empire of the Steppes: A History of Central Asia, (Rutgers University Press, 2002), 157; "...the Seljuk court at Konya adopted Persian as its official language."

- Bernard Lewis, Istanbul and the Civilization of the Ottoman Empire, (University of Oklahoma Press, 1963), 29; "The literature of Seljuk Anatolia was almost entirely in Persian...".

- Mehmed Fuad Koprulu (2006). Early Mystics in Turkish Literature. p. 207.

- Andrew Peacock and Sara Nur Yildiz, The Seljuks of Anatolia: Court and Society in the Medieval Middle East, (I.B. Tauris, 2013), 132; "The official use of the Greek language by the Seljuk chancery is well known".

- Beihammer, Alexander Daniel (2017). Byzantium and the Emergence of Muslim-Turkish Anatolia, ca. 1040-1130. New York: Routledge. p. 15.

- Bernard Lewis, Istanbul and the Civilization of the Ottoman Empire, 29; "Even when the land of Rum became politically independent, it remained a colonial extension of Turco-Persian culture which had its centers in Iran and Central Asia","The literature of Seljuk Anatolia was almost entirely in Persian ..."

- "Institutionalisation of Science in the Medreses of pre-Ottoman and Ottoman Turkey", Ekmeleddin Ihsanoglu, Turkish Studies in the History and Philosophy of Science, ed. Gürol Irzik, Güven Güzeldere, (Springer, 2005), 266; "Thus, in many of the cities where the Seljuks had settled, Iranian culture became dominant."

- Andrew Peacock and Sara Nur Yildiz, The Seljuks of Anatolia: Court and Society in the Medieval Middle East, (I.B. Tauris, 2013), 71-72

- Turko-Persia in Historical Perspective, ed. Robert L. Canfield, (Cambridge University Press, 1991), 13.

- Alexander Kazhdan, "Rūm" The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium (Oxford University Press, 1991), vol. 3, p. 1816. Paul Wittek, Rise of the Ottoman Empire, Royal Asiatic Society Books, Routledge (2013), p. 81: "This state too bore the name of Rûm, if not officially, then at least in everyday usage, and its princes appear in the Eastern chronicles under the name 'Seljuks of Rûm' (Ar.: Salâjika ar-Rûm). A. Christian Van Gorder, Christianity in Persia and the Status of Non-muslims in Iran p. 215: "The Seljuqs called the lands of their sultanate Rum because it had been established on territory long considered 'Roman', i.e. Byzantine, by Muslim armies."

- ^ John Joseph Saunders, The History of the Mongol Conquests, (University of Pennsylvania Press, 1971), 79.

- Sicker, Martin, The Islamic world in ascendancy: from the Arab conquests to the siege of Vienna , (Greenwood Publishing Group, 2000), 63-64.

- ^ Anatolia in the period of the Seljuks and the "beyliks", Osman Turan, The Cambridge History of Islam, Vol. 1A, ed. P.M. Holt, Ann K.S. Lambton and Bernard Lewis, (Cambridge University Press, 1995), 244-245.

- A.C.S. Peacock and Sara Nur Yildiz, The Seljuks of Anatolia: Court and Society in the Medieval Middle East, (I.B. Tauris, 2015), 29.

- ^ Alexander Mikaberidze, Historical Dictionary of Georgia, (Rowman & Littlefield, 2015), 184.

- ^ Claude Cahen, The Formation of Turkey: The Seljukid Sultanate of Rum: Eleventh to Fourteenth, transl. & ed. P.M. Holt, (Pearson Education Limited, 2001), 42.

- Tricht 2011, p. 355.

- Ring, Watson & Schellinger 1995, p. 651.

- A.C.S. Peacock, "The Saliūq Campaign against the Crimea and the Expansionist Policy of the Early Reign of'Alā' al-Dīn Kayqubād", Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, Vol. 16 (2006), pp. 133-149.

- Kastritsis 2013, p. 26.

- Saljuqs: Saljuqs of Anatolia, Robert Hillenbrand, The Dictionary of Art, Vol.27, Ed. Jane Turner, (Macmillan Publishers Limited, 1996), 632.

- Rudi Paul Lindner, Explorations in Ottoman Prehistory, (University of Michigan Press, 2003), 3.

- "A Rome of One's Own: Reflections on Cultural Geography and Identity in the Lands of Rum", Cemal Kafadar,Muqarnas, Volume 24 History and Ideology: Architectural Heritage of the "Lands of Rum", Ed. Gülru Necipoğlu, (Brill, 2007), page 21.

- Ágoston, Gábor; Masters, Bruce Alan (2010). Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4381-1025-7., page 40

- The Oriental Margins of the Byzantine World: a Prosopographical Perspective, / Rustam Shukurov, in Herrin, Judith; Saint-Guillain, Guillaume (2011). Identities and Allegiances in the Eastern Mediterranean After 1204. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 978-1-4094-1098-0., pages 181–191

- A sultan in Constantinople:the feasts of Ghiyath al-Din Kay-Khusraw I, Dimitri Korobeinikov, Eat, drink, and be merry (Luke 12:19) - food and wine in Byzantium, in Brubaker, Leslie; Linardou, Kallirroe (2007). Eat, Drink, and be Merry (Luke 12:19): Food and Wine in Byzantium : Papers of the 37th Annual Spring Symposium of Byzantine Studies, in Honour of Professor A.A.M. Bryer. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7546-6119-1., page 96

- West Asia:1000-1500, Sheila Blair and Jonathan Bloom, Atlas of World Art, Ed. John Onians, (Laurence King Publishing, 2004), 130.

- Architecture (Muhammadan), H. Saladin, Encyclopaedia of Religion and Ethics, Vol.1, Ed. James Hastings and John Alexander, (Charles Scribner's son, 1908), 753.

- Armenia during the Seljuk and Mongol Periods, Robert Bedrosian, The Armenian People From Ancient to Modern Times: The Dynastic Periods from Antiquity to the Fourteenth Century, Vol. I, Ed. Richard Hovannisian, (St. Martin's Press, 1999), 250.

- Lost in Translation: Architecture, Taxonomy, and the "Eastern Turks", Finbarr Barry Flood, Muqarnas: History and Ideology: Architectural Heritage of the "Lands of Rum, 96.

- Rodriguez, Junius P. (1997). The Historical Encyclopedia of World Slavery. ABC-CLIO. p. 306. ISBN 978-0-87436-885-7., page 306

Sources

- Bosworth, C. E. (2004). The New Islamic Dynasties: a Chronological and Genealogical Manual. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0-7486-2137-7.

- Bektaş, Cengiz (1999). Selcuklu Kervansarayları, Korunmaları Ve Kullanlmaları üzerine bir öneri: A Proposal regarding the Seljuk Caravanserais, Their Protection and Use (in Turkish and English). ISBN 975-7438-75-8.

- Kastritsis, Dimitris (2013). "The Historical Epic "Ahval-i Sultan Mehemmed" (The Tales of Sultan Mehmed) in the Context of Early Ottoman Historiography". Writing History at the Ottoman Court: Editing the Past, Fashioning the Future. Indiana University Press.

- Ring, Trudy; Watson, Noelle; Schellinger, Paul, eds. (1995). Southern Europe: International Dictionary of Historic Places. Vol. 3. Routledge.

- Tricht, Filip Van (2011). The Latin Renovatio of Byzantium: The Empire of Constantinople (1204-1228). Translated by Longbottom, Peter. Brill.

External links

- Yavuz, Ayşıl Tükel. "The concepts that shape Anatolian Seljuq caravanserais" (PDF). ArchNet. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-07-04.

- "List of Seljuk edifices". ArchNet. Archived from the original on 2007-04-05.

- Katharine Branning. "Examples of caravanserais built by the Anatolian Seljuk Sultanate". Turkish Hans.

| Seljuk Sultanate of Rum | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| House of Seljuk | |

|---|---|

| Early Seljukids | |

| Sultans of the Seljuk Empire (1037–1194) | |

| Governors of Khorasan (1040–1118) | |

| Governors of Kerman (1048–1188) | |

| Governors of Damascus (1076–1105) | |

| Governors of Aleppo (1086–1117) | |

| Sultans of Rum (1092–1307) | |

| States in late medieval Anatolia (after 1071) | |

|---|---|

| Muslim states |

|

| Christian states | |

| History of Anatolia | |

|---|---|

|