| Revision as of 13:03, 23 February 2005 view sourceVadakkan (talk | contribs)Pending changes reviewers2,877 editsm →Special character← Previous edit | Revision as of 09:47, 24 February 2005 view source Santhoshguru~enwiki (talk | contribs)53 edits →Special characterNext edit → | ||

| Line 101: | Line 101: | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ]]] | ]]] | ||

| The special character 'ஃ' (pronounced 'akh') is called ''āytham'' in the Tolkāppiyam (''see'' ''Tolkāppiyam'' 1:1:2). The ''āytham'' is rarely used by itself: it normally serves a purely grammatical function as an independent vowel form, the equivalent of the ] of plain consonants. The rules of pronunciation given in the Tolkāppiyam suggest that the ''āytham'' could have |

The special character 'ஃ' (pronounced 'akh') is called ''āytham'' in the Tolkāppiyam (''see'' ''Tolkāppiyam'' 1:1:2). The ''āytham'' is rarely used by itself: it normally serves a purely grammatical function as an independent vowel form, the equivalent of the ] of plain consonants. The rules of pronunciation given in the Tolkāppiyam suggest that the ''āytham'' could have ] the sounds it was combined with. Although the character was common in classical Tamil, it fell out of use in the early modern period and is now very rare in written Tamil. It is occasionally used with a 'p' (as ஃப) to represent the phoneme . | ||

| The ''āytham'' is also called ''ahenam'' (literally, 'the "ah" sound') or ''āyutha ezhuthu'' (''aayutham'' - weapon or device used in wars, ''ezhuthu'' - character) as it resembles the three dots found on a '']'' used by ] in wars of olden days. | The ''āytham'' is also called ''ahenam'' (literally, 'the "ah" sound') or ''āyutha ezhuthu'' (''aayutham'' - weapon or device used in wars, ''ezhuthu'' - character) as it resembles the three dots found on a '']'' used by ] in wars of olden days. | ||

Revision as of 09:47, 24 February 2005

Tamil is a Dravidian language predominantly spoken in southern India and Sri Lanka, with smaller communities of speakers in many other countries. In 1996, it was the 18th most spoken language in the world with over 74 million speakers worldwide.

As one of the few living classical languages, Tamil has an unbroken literary tradition of over two millenia. The written language has changed little during this period, with the result that classical literature is as much a part of everyday Tamil as modern literature. Tamil schoolchildren, for example, are still taught the alphabet using the átticúdi, an alphabet rhyme written around the first century AD.

The name 'Tamil' is an anglicised form of the native name தமிழ் (IPA /tæmɪɻ/). The final letter of the name, usually transcribed as the lowercase l or zh, is a retroflex r believed to only exist in Tamil and Malayalam. In phonetic transcriptions, it is usually represented by the retroflex approximant.

error: ISO 639 code is required (help)

History

Like the other Dravidian languages, but unlike most of the other established literary languages of India, the origins of Tamil are independent of Sanskrit. Tamil has the longest unbroken literary tradition amongst the Dravidian languages. Tamil tradition dates the oldest works to several millennia ago, but the earliest examples of Tamil writing we have today are in inscriptions from the third century BC, which are written in an adapted form of the Brahmi script (Mahadevan, 2003). Dating the earliest literary works themselves is difficult, in large part because they were preserved either in palm leaf manuscripts (implying repeated copying and recopying) or through oral transmission. Internal linguistic evidence, however, indicates that the oldest extant works were probably composed sometime between the second century BC and the third century AD. The earliest available text is the Tolkaappiyam, a work on poetics and grammar which describes the language of the classical period, portions of which date back to around 200 BC. Archaelogical evidence obtained from inscriptions excavated in 2005 dates the language to around 500 BC .

Linguists categorise Tamil literature and language into three periods: ancient (200 BC to 700 AD), medieval (700 AD to 1500 AD) and modern (1500 AD to the present). During the medieval period, a number of Sanskrit loan words were absorbed by Tamil, which were sought to be removed by many purists during the 1900s, notably by Parithimaar kalaignar and Maraimalai adigal. This movement was called thanith thamizh iyakkam (meaning pure tamil movement). As a result of this, Tamil in formal documents, public speeches and scientific discourses is free of Sanskrit loan words largely. Around 800-1000 AD, Malayalam is believed to have evolved into a distinct language.

Classification

Tamil is a member of the Tamil languages group of languages that includes Irula, Kaikadi, Betta Kurumba, Sholaga, and Yerukula languages. This group is a subgroup of the Tamil-Malayalam languages, which falls under a subgroup of Tamil-Kodagu languages, which in turn is a subgroup of Tamil-Kannada languages. The Tamil-Kannada languages belong to the Southern branch of the Dravidian language family.

Malayalam, spoken by the people of Kerala state - which borders Tamil Nadu - closely resembles Tamil in vocabulary, syntax and writing system.

Geographic distribution

Tamil is the first language of the majority in the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu, and in northern and north-eastern Sri Lanka. The language is also spoken in other parts of these two countries, most notably in the Indian states of Karnataka, Kerala and Maharashtra, and in Colombo and the hill country in Sri Lanka.

During the 19th and early 20th centuries, Tamil-speaking indentured labourers from India and Sri Lanka were sent to many parts of the British empire where they founded Tamil-speaking communities. There are currently sizeable Tamil-speaking populations descended from them in Singapore, Malaysia, Mauritius and South Africa. Many people in Guyana, Fiji, Suriname and Trinidad and Tobago have Tamil origins, but the language is not spoken there any longer.

Groups of more recent emigrants - primarily refugees from the Sri Lankan civil war, but also a few economic migrants - exist in Australia, Canada, the USA and most western European countries.

Legal status

Tamil is the official language of the Indian state of Tamil Nadu, and is one of 22 nationally-recognised languages under the Indian Constitution. Tamil is also an official language of Sri Lanka, Malaysia and Singapore, and has constitutional recognition in South Africa.

In addition, Tamil was recognised as a classical language by the Government of India in 2004, following a campaign by several Tamil associations supported by academics from India and abroad, most notably Professor George L. Hart, who occupies the Chair in Tamil Studies at the University of California, Berkeley. (See his statement.) It was the first Indian language to be so recognised. The recognition was announced by the President of India, Dr. Abdul Kalam, in a joint sitting of both houses of the Indian Parliament on June 6, 2004.

(See item 41 of his address and the BBC news item on the formal approval by the Indian Cabinet.)

Spoken and literary variants

In addition to its various dialects, Tamil also exhibits a rather sharp diglossia between its formal or classic variety, called centamil, and its colloquial form, called koduntamil, a broad term which traditionally referred to all spoken Tamil dialects rather than any one standard form. Diglossia has existed in the language since ancient times - the language used in early temple inscriptions differs quite significantly from the language of classical poetry. In consequence, standard centamil is not based on the speech of any one region, a fact which has helped keep the written language mostly the same across various Tamil speaking regions.

In modern times, centamil is generally used in formal writing and speech. It is, for example, the language of textbooks, of much of Tamil literature and of public speaking and debate. In recent times, however, koduntamil has been making inroads into areas that have traditionally been considered the province of centamil. Most contemporary cinema, theatre and popular entertainment on television and radio, for example, is in koduntamil, and many politicians use it to bring themselves closer to their audience.

Spoken dialects did not have much prestige - the grammatical rules of literary centamil were believed to have been formulated by the gods and therefore seen as being the only correct speech (see e.g. Kankeyar, 1840). In contrast to most European languages, therefore, Tamil did not have a standard spoken form for much of its history. In modern times, however, the increasing use of koduntamil has led to the emergence of unofficial 'standard' spoken dialects. In India, the 'standard' koduntamil is based on "educated non-brahmin speech", rather than on any one dialect (Schiffman, 1998), but has been significantly influenced by the dialects of Thanjavur and Madurai. In Sri Lanka the standard is based on the dialect of Jaffna.

Dialects

Tamil dialects are mainly differentiated from each other by the fact that they have undergone different phonological changes and sound shifts in evolving from Old Tamil. Thus the word for "here" - inge in chentamil - has evolved into inga in the dialect of Thanjavur, ingane in the dialect of Tirunelveli, inguttu in the dialect of Ramanathapuram, ingale and ingade in various northern dialects and unga in some dialects of Jaffna.

Although most Tamil dialects do not differ very significantly in their vocabulary, there are a few exceptions. The dialects spoken in Sri Lanka retain many words that are not in everyday use in India, and use many other words slightly differently. The dialect of the Iyers of Palakkad has a large number of Malayalam loanwords, and has also been influenced by Malayalam syntax. Finally, the Hebbar and Mandyam dialects, spoken by groups of Tamil vaishnavites who migrated to Karnataka in the 11th century, retains many features of the Vainava paribasai, a special form of Tamil designed in the 9th and 10th centuries to reflect Vaishnavite religious and spiritual values.

Tamil dialects vary according to both region and community. Several castes have their own dialects which most members of that caste traditionally used regardless of where they come from. Some of these differences have begun to fade away in recent years as a result of the anti-casteist movement, but many traces remain and it is often possible to identify a person's caste by their speech.

The Ethnologue lists twenty-two current dialects of Tamil, including Adi Dravida, Aiyar, Aiyangar, Arava, Burgandi, Kasuva, Kongar, Korava, Korchi, Madrasi, Parikala, Pattapu Bhasha, Sri Lanka Tamil, Malaya Tamil, Burma Tamil, South Africa Tamil, Tigalu, Harijan, Sanketi, Hebbar, Tirunelveli and Madurai. Other known dialects are Kongu and Kumari.

Writing system

Main article: Tamil alphabet

Tamil writing is phonetic, and is subject to well-defined rules of elision and euphony. The present script used to write Tamil text is believed to have evolved from the Brahmi script of the Ashokan era. Later, a southern variant of the Brahmi script evolved into the Grantha script, which was used to write both Sanskrit and Tamil texts. Around the 15th century, a new script called vettezhuthu (meaning letters that are cut) evolved in order to make it easy for creating inscriptions on stone. Some people also call this as vattezhuthu (meaning curved letters). Around 1935, Periyar suggested some changes to make it amenable for printing. Some of these suggestions were incorporated by the then MG Ramachandran government in 1975.

While the evolution of the script was happening, many Sanskrit words also began to be used in Tamil. To facilitate writing these words, some characters from the grantha script are still being retained. However, there are many purists who would argue against the use of such characters as there are well-defined rules in Tolkaappiyam for Tamilising loan words.

Sounds

Main article: Tamil alphabet

| Audio: A Tamil tongue twister |

| ēḻaik kiḻavaṉ vāḻaippaḻatōlmēl (info)(help) |

| The sentence literally means: "An old pauper stepped on a banana peel, and slipped, slithered, and fell" |

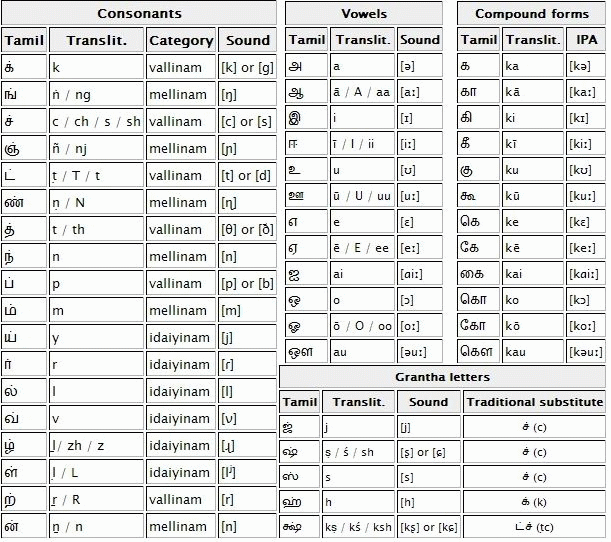

The Tamil alphabet has 12 vowels and 18 consonants. These combine to form 216 compound characters. There is one special character (aaytha ezutthu), giving a total of 247 characters.

Vowels

The vowels are called uyir ezhuthu (uyir - life, ezhuthu - letter). The vowels are classified into short and long (five of each type) and two diphthongs.

The long (nedil) vowels are about twice as long as the short (kuRil) vowels. The diphthongs are usually pronounced about 1.5 times as long as the short vowels, though most grammatical texts place them with the long vowels.

Consonants

The consonants are classified into three categories with 6 in each category: vallinam - hard, mellinam - soft or nasal, and idayinam - medium. Tamil has very restricted consonant clusters (eg: never word initial etc.) and has neither aspirated nor voiced stops. Some scholars have suggested that in Chenthamil (which refers to Tamil as it existed before Sanskrit words were borrowed), stops were voiceless when at the start of a word and voiced allophonically otherwise. However, no such distinction is observed by most modern Tamil speakers.

The alphabet chart below lists the consonants in isolated form (sans vowel sounds), indicated by the overdot diacritic, and also shows how they form their compound forms, using the consonant 'k' as an example. As the chart indicates, the compound forms are sometimes ligatures with signs representing the vowel sound before and/or after the consonant glyph.

Special character

The special character 'ஃ' (pronounced 'akh') is called āytham in the Tolkāppiyam (see Tolkāppiyam 1:1:2). The āytham is rarely used by itself: it normally serves a purely grammatical function as an independent vowel form, the equivalent of the overdot diacritic of plain consonants. The rules of pronunciation given in the Tolkāppiyam suggest that the āytham could have glottalised the sounds it was combined with. Although the character was common in classical Tamil, it fell out of use in the early modern period and is now very rare in written Tamil. It is occasionally used with a 'p' (as ஃப) to represent the phoneme .

The āytham is also called ahenam (literally, 'the "ah" sound') or āyutha ezhuthu (aayutham - weapon or device used in wars, ezhuthu - character) as it resembles the three dots found on a shield used by infantry in wars of olden days.

Phonology

Unlike most other Indian languages, Tamil does not have aspirated consonants. The Tamil script also does not distinguish between voiced and unvoiced sounds, although both are present in the spoken language. Voiced and unvoiced sounds are not quite allophones, however. Tamil speakers are aware of the difference, and the Tolkāppiyam cites detailed rules as to when a letter is to be pronounced with voice and when it is to be pronounced unvoiced. The letter 't', for example, was to be pronounced voiced if it was at the beginning of a word, doubled or followed another hard consonant, and unvoiced otherwise.

With the exception of one rule - the pronunciation of the letter c at the beginning of a word - these rules are largely followed even today in pronuncing centamil. The position is, however, much more complex in relation to spoken koduntamil. The pronunciation of southern dialects and the dialects of Sri Lanka continues to reflect these rules to a large extent, though not completely. In northern dialects, however, sound shifts have changed many words so substantially that these rules no longer describe how words are pronounced. In addition many, but not all, Sanskrit loan words are pronounced in Tamil as they were in Sanskrit, even if this means that consonants which should be unvoiced according to the Tolkāppiyam are voiced.

Phonologists are divided in their opinion over why written Tamil did not distinguish between voiced and unvoiced characters. One point of view is that Tamil never had conjunct consonants or voiced stops - voice was rather the result of elision or sandhi. Consequently unlike Indo-European languages and other Dravidian languages, Tamil did not need separate characters for voiced consonants. A slightly different theory holds that voiced consonants were at one stage allophones of unvoiced consonants, and the lack of distinction between the two in the modern script merely reflects that.

Elision

Elision is the reduction in the duration of sound of a phoneme when preceded by or followed by certain other sounds. There are well-defined rules for elision in Tamil. They are categorised into different classes based on the phoneme which undergoes elision.

- Kutriyalukaram - the vowel u

- Kutriyalikaram - the vowel i

- Aiykaarakkurukkam - the diphthong ai

- Oukaarakkurukkam - the diphthong au

- Aaythakkurukkam - the special character akh (aayutham)

- Makarakkurukkam - the phoneme m

Grammar

Much of Tamil grammar is extensively described in the oldest available grammar book for Tamil, the Tolkāppiyam. Modern Tamil writing is largely based on the 13th century grammar Naṉṉūl which restated and clarified the rules of the Tolkāppiyam, with some modifications.

Tamil words

Tamil, like other Dravidian languages, is an agglutinative language. Tamil words consist of a lexical root to which one or more affixes are attached. In written Tamil, the morphemes that make up individual words are usually easily separable and analysable.

Most Tamil affixes are suffixes. Tamil suffixes can be derivational suffixes, which either change the part of speech of the word or its meaning, or inflectional suffixes, which mark categories such as person, number, mood, tense, etc. There is no absolute limit on the length and extent of agglutination, which can lead to long words with a large number of suffixes, which would require several words or a sentence in English. To give an example, the word pōkamuṭiyātavarkaḷukkāka means "for the sake of those who cannot go", and consists of the following morphemes:

| pōka | muṭi | y | āta | var | kaḷ | ukku | āka | ||||||||||||||||

| go | accomplish | puNarci | negation (impersonal) |

nominative termination he/she who does |

plural marker | to | for |

Words formed as a result of the agglutinative process are often difficult to translate. According to Today Translations, a British translation service, the Tamil word "செல்லாதிருப்பவர்" (sellaathiruppavar, meaning a certain type of truancy †) is ranked 8 in The Most Untranslatable Word In The World list.

Parts of speech

Nouns

The first category of words in Tamil is peyarcol or "name-words", a broad classification which includes all nouns, numerals, pronouns and some adjectives. The peyarcol are divided into two classes (tiṇai) - the "rational" (uyartiṇai), and the "irrational" (aḵṟiṇai), each of which has its own sub-classes as shown in the table below. Humans and deities are normally classified as "rational", and animals, objects and everything else as irrational. However, these classifications are not absolute - the irrational form can be used contemptuously for humans. The collective form for rational nouns is also used as an honorific, and a gender-neutral singular form. The "many" form of irrational nouns - which technically ought to serve as a plural - is rarely used in speech or writing. As the example in the table indicates, person, number (singular and plural) and gender are often indicated through suffixes.

| peyarcol (Name-words) | ||||

| uyartiṇai (rational) |

aḵṟiṇai (irrational) | |||

| āṇpāl Male |

peṇpāl Female |

palarpāl Collective |

oṉṟaṉpāl One |

palaviṉpāl Many |

| Example: the Tamil words for "doer" | ||||

| ceytavaṉ He who did |

ceytavaḷ She who did |

ceytavar They who did |

ceytatu That which did |

ceytavai Those ones which did |

Suffixes are also used to perform the functions of cases or postpositions. Traditional grammars tried to group the various suffixes into 8 cases corresponding to the cases used in Sanskrit. These were the nominative, accusative, dative, sociative, genitive, instrumental, locative, and ablative. Modern grammarians, however, argue that this classification is artificial, and that Tamil usage is best understood if each suffix or combination of suffixes is seen as marking a separate case. (Schiffman, 1999).

Tamil nouns can also take one of four prefixes, i, a, u and e which are functionally equivalent to demonstratives in English. For example, the word vaḻi meaning "way" can take these to produce ivvaḻi "this way", avvaḻi "that way", uvvaḻi "the medial way" and evvaḻi "which way".

Verbs

Like Tamil nouns, Tamil verbs are also inflected through the use of suffixes. A typical Tamil verb form will have a number of suffixes, which show person, number, mood, tense and voice, as is shown by the following example aḷintukkoṇṭiruntēṉ "(I) was being destroyed":

| aḷi | intu | koṇṭu | irunta | ēn | ||||||||

| root destroy |

voice marker past tense object voice |

tense marker during |

tense marker past progressive |

person marker first person, singular |

Person and number are indicated by suffixing the oblique case of the relevant pronoun (ēn in the above example). The suffixes to indicate tenses and voice are formed from grammatical particles, which are added to the stem.

Tamil has two voices. The first - used in the example above - indicates that the subject of the sentence undergoes or is the object of the action named by the verb stem, and the second indicates that the subject of the sentence directs the action referred to by the verb stem. These voices are not equivalent to the notions of transitivity or causation, or to the active-passive or reflexive-nonreflexive division of voices found in Indo-european languages.

Tamil has three simple tenses - past, present, and future - indicated by simple suffixes, and a series of perfects, indicated by compound suffixes. Mood is implicit in Tamil, and is normally reflected by the same morphemes which mark tense categories. These signal whether the happening spoken of in the verb is unreal, possible, potential, or real.

Auxiliaries

Tamil has no articles. Definiteness and indefiniteness are either indicated by special grammatical devices, such as using the number "one" as an indefinite article, or by the context. In the first person plural, Tamil makes a distinction between inclusive pronouns that include the listener and exclusive pronouns that do not. Tamil does not distinguish between Adjectives and adverbs - both fall under the category uriccol. Conjunctions are called iṭaiccol.

Verb auxiliaries are used to indicate attitude, a grammatical category which shows the state of mind of the speaker, and his attitude about the event spoken of in the verb. Common attitudes include pejorative opinion, antipathy, relief felt at the conclusion of an unpleasant event or period, and unhappiness at or apprehension about the eventual result of a past or continuing event.

Sentence structure

Word order in Tamil is rather rigid. Except in poetry, the subject must precede the object, and the verb must conclude the sentence. In a standard sentence, therefore, the order is usually Subject Object Verb (SOV).

Tamil is a null subject language. Not all Tamil sentences have subjects, verbs and objects. It is possible to construct valid sentences that have only a verb - such as muṭintuviṭṭatu ("It is completed") - or only a subject and object, such as atu eṉ vīṭu ("That is my house"). The elements that are present, however, must follow the SOV order.

Vocabulary

Modern Tamil vocabulary still retains most of the words from classical Tamil. Due to this and because of the emphasis on learning classical works like Tirukkural, classical Tamil is comprehensible in various degrees to most native speakers of today. However, a number of Sanskrit loan words have been adapted and used commonly in modern Tamil. But, unlike some other Dravidian languages, these words are restricted mainly to spiritual terminology and abstract nouns. Besides Sanskrit, there are a few loan words from Persian and Arabic implying trade ties in ancient times. Since around the 20th century AD, English words have also begun to be used freely in colloquial Tamil. Some modern technical terminology is borrowed from English, though attempts are being made to have a pure Tamil technical terminology. Many individuals, and some institutions like the Tamil Virtual University have generated technical dictionaries for Tamil.

There are also many instances of Tamil loan words in other languages. Popular examples are cheroot (churuttu meaning "rolled up"), mango and catamaran (from kattu maram meaning "bundled logs"). For more such words, see here.

Examples

A sample passage in Tamil script with a Romanised transcription:

ஆசிரியர் வகுப்பறையுள் நுழைந்தார். அவர் உள்ளே நுழைந்தவுடன் மாணவர்கள் எழுந்தனர். வளவன் மட்டும் தன் அருகில் நின்றுகொண்டிருந்த மாணவி கனிமொழியுடன் பேசிக் கொண்டிருந்தான். நான் அவனை எச்சரித்தேன்.

aasiriyar vakuppaRaiyuL nuzhainthaar. avar uLLE nuzhainthavudan maaNavarkaL ezhunthanar. vaLavan mattum than arukil ninRu kondiruntha maaNavi kanimozhiyudan pEsik kondirunthaan. naan avanai echarithEn.

English translation of the passage given above:

The teacher entered the classroom. As soon as he entered, the students got up. Valavan alone was talking to Kanimozhi who was standing next to him. I cautioned him.

Note: Tamil does not have articles. The article the used above is merely an artefact | of translation.

| Word (romanised) | Translation | Morphemes | Part of speech | Person, Gender, Tense | Case | Number | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aasiriyar | Teacher | aasiriyar | noun | n/a, gender-neutral, n/a | Nominative | honorific plural indicated by suffix ar | use of aasiriyai for feminine gender (in honorific sense) is not uncommon |

| vakuppaRaiyuL | inside the class room | vakuppu+aRai +uL |

adverb | n/a | Locative | n/a | Sandhi (called puṇarci in Tamil) rules in Tamil require complicated euphonic changes during agglutination (such as the introduction of y in this case) |

| nuzhainthaar | entered | nuzhainthaar | verb | third, gender-neutral, past | honorific plural | the masculine and feminine equivalents nuzhainthaan and nuzhainthaaL are almost invariably replaced by the collective nuzhainthaar in a honorific context | |

| avar | He | avar | pronoun | third, gender-neutral, n/a | Nominative | honorific plural indicated by suffix ar | the masculine and feminine forms avan and avaL are not used in a honorific sense |

| uLLE | inside | uLLE | adverb | n/a | n/a | ||

| nuzhainthavudan | upon entering | nuzhaintha + udan |

adverb | n/a | n/a | Sandhi rules require a v to be inserted between a a and a u during agglutination. | |

| maaNavarkaL | students | maaNavarkaL | collective noun | n/a, masculine, often used with gender-neutral connotation, n/a | Nominative | plural indicated by suffix aL | |

| ezhunthanar | got up | ezhunthanar | verb | third, gender-neutral, past | plural | ||

| VaLavan | VaLavan (name) | VaLavan | Proper noun | n/a, masculine, usually indicated by suffix n, n/a | Nominative | singular | |

| mattum | alone | mattum | adjective | n/a | n/a | ||

| than | his (self) own | than | pronoun | n/a, gender-neutral, n/a | singular | ||

| arukil | near (lit. "in nearness") | aruku + il | adverb | n/a | Locative | n/a | The postposition il indicates the locative case |

| ninRu kondiruntha | standing | ninRu + kondu + iruntha | adverb | n/a | n/a | the verb has been morphed into an adverb by the incompleteness due to the terminal a | |

| maaNavi | student | maaNavi | pronoun | n/a, feminine, n/a | singular | ||

| kanimozhiyudan | with Kanimozhi (name of a person) | kanimozhi + udan | adverb | n/a | Comitative | n/a | the name Kanimozhi literally means sweet language |

| pEsik kondirunthaan | had been chatting | pEsi + kondu +irunthaan | verb | third, masculine, past perfect | singular | continuousness indicated by the incompleteness brought by kondu | |

| naan | I | naan | pronoun | first person, gender-neutral, n/a | Nominative | singular | |

| avanai | him | avanai | pronoun | third, masculine, n/a | Accusative | singular | the postposition ai indicates accusative case |

| echarithEn | cautioned | echarithEn | verb | first, indicated by suffix En, gender-neutral, past | singular, plural would be indicated by substituting En with Om |

Translations of commonly used phrases

Following are translations of some commonly used phrases.

- Tamil: தமிழ்/Tamizh /tamiɮ/

- hello: வணக்கம்/Vanakkam /vanakːam/

- good-bye: சென்று வருகிறேன்/sentru varukireen /sentu varukireen/

- please: தயவு செய்து/dayavu seithu /tajavu sei/

- thank you: நன்றி/nandri /nantʕi/

- sorry: மன்னிக்கவும்/mannikkavum /

- that one: அது/adhu /a tʰu/

- how much?: எவ்வளவு/evvalavu /evːalavu/

- yes: ஆம்/aam /aːm/

- no: இல்லை/illai /ilːaj/

- I don't understand: எனக்குப் புரியவில்லை / enakku puriyavillai/

- Where's the bathroom?: குளியலறை எங்கே உள்ளது? / kuLiyalarai enge uLLadhu?/

- generic toast (not used in formal conversations and to elders): (Hey): டேய்!/dei /de:i/

- English: ஆங்கிலம்/aangilam /aːŋilam/

- Do you speak English?: நீங்கள் ஆங்கிலம் பேசுவீர்களா? / neengaL aangilam pEsuveergaLaa?/

References

Modern works

- Kāṅkēyar (1840). Uriccol nikaṇṭurai. Putuvai, Kuver̲an̲mā Accukkūṭam.

- Mahadevan, Iravatham (2003). Early Tamil Epigraphy from the Earliest Times to the Sixth Century A.D. Cambridge, Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674012275.

- Natarajan, T. (1977), The language of Sangam literature and Tolkāppiyam. Madurai, Madurai Publishing House.

- Pope, GU (1862). First catechism of Tamil grammar: Ilakkaṇa vin̲aviṭai - mutar̲puttakam. Madras, Public Instruction Press.

- Pope, GU (1868). A Tamil hand-book, or, Full introduction to the common dialect of that language. (3rd ed.). Madras, Higginbotham & Co.

- Rajam, VS (1992). A Reference Grammar of Classical Tamil Poetry. Philadelphia, The American Philosophical Society. ISBN 087169199X.

- Schiffman, Harold F. (1998). "Standardization or restandardization: The case for 'Standard' Spoken Tamil". Language in Society 27, 359–385.

- Schiffman, Harold F. (1999). A Reference Grammar of Spoken Tamil. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521640741.

Ancient works

- Pavaṇanti Muṉivar, Naṉṉūl Mūlamum Viruttiyuraiyum, (A. Tāmōtaraṉ; ed., 1999), International Institute of Tamil Studies, Chennai.

- Pavaṇanti, Naṉṉūl mūlamum Kūḻaṅkaittampirāṉ uraiyum (A. Tāmōtaraṉ ed., 1980). Wiesbaden, Franz Steiner Verlag.

- Taṇṭiyāciriyar, Taṇṭiyāciriyar iyaṟṟiya taṇṭiyalaṅkāram: Cuppiramaṇiya Tēcikar uraiyuṭaṉ. (Ku. Mutturācaṉ ed., 1994). Tarmapuri, Vacanta Celvi Patippakam.

- Tolkāppiyar, Tolkāppiyam Iḷampūraṇar uraiyuṭaṉ (1967 reprint). Ceṉṉai, TTSS.

External links

General

- Ethnologue report

- Omniglot resource

- Rosetta Project Archive

- Language Museum report

- UCLA Tamil Profile

- A brief review of its history and characteristics

- International Forum for Information Technology in Tamil

- Tamil Language & Literature

Resources for learning

- UPENN course page - University of Pennsylvania's web based courses for learning Tamil

- Tamil virtual University has the largest collection of digitised Tamil literary works and web based courses for learning Tamil

- IITS - Institute of Indology and Tamil Studies,University of Cologne ,Germany

Fonts and Encodings

- Unicode Chart - Unicode Chart for Tamil (PDF)

- Unicode Converter - Online JavaScript tool to convert text in various Tamil encodings into Unicode

- Tamil fonts - Links to download various Tamil fonts

- NLS Information - NLS Information page for Windows XP

- thamizhlinux.org - A community website for everything Linux and Open Source in Tamil