| Revision as of 14:30, 15 June 2021 editWikideas1 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users13,342 editsm →See also: negative income tax← Previous edit | Revision as of 04:36, 23 December 2021 edit undoIsland Pelican (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users1,251 edits I edited the phrasing to be more neutralNext edit → | ||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| The '''welfare trap''' (or '''unemployment trap''' or '''poverty trap''' in British English) theory asserts that ] and ] systems can jointly contribute to keep people on ] because the withdrawal of ]ed benefits that comes with entering low-paid work causes there to be no significant increase in total income. |

The '''welfare trap''' (or '''unemployment trap''' or '''poverty trap''' in British English) theory asserts that ] and ] systems can jointly contribute to keep people on ] because the withdrawal of ]ed benefits that comes with entering low-paid work causes there to be no significant increase in total income. According to this theory, an individual sees that the ] of returning to work is too great for too little a financial return, and this can create a ] to not work.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.learnliberty.org/blog/the-welfare-cliff-and-why-many-low-income-workers-will-never-overcome-poverty/|title=The Welfare Cliff and Why Many Low-Income Workers Will Never Overcome Poverty|website=Learn Liberty|date=August 24, 2016|first=Howard|last=Baetjer}}</ref> | ||

| ==Different definitions== | ==Different definitions== | ||

Revision as of 04:36, 23 December 2021

For the general concept of self-reinforcing mechanisms which maintain poverty, see Poverty trap.| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Welfare trap" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (May 2007) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

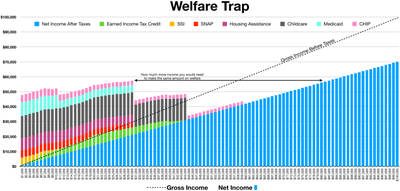

The welfare trap (or unemployment trap or poverty trap in British English) theory asserts that taxation and welfare systems can jointly contribute to keep people on social insurance because the withdrawal of means-tested benefits that comes with entering low-paid work causes there to be no significant increase in total income. According to this theory, an individual sees that the opportunity cost of returning to work is too great for too little a financial return, and this can create a perverse incentive to not work.

Different definitions

The term used for this concept varies depending on country. In the United States, where government benefit payments are colloquially referred to as "welfare", the welfare trap often indicates that a person is completely dependent on benefits, with little or no hope of self-sufficiency. The welfare trap is also known as the unemployment trap or the poverty trap, with both terms frequently being used interchangeably as they often go hand-in-hand, but there are subtle differences.

In other contexts, the terms "welfare trap" and "poverty trap" are clearly distinguished. For example, a Southern African Regional Poverty Network report on social protection clarifies that "poverty trap a structural condition from which people cannot rescue themselves despite their best efforts. A welfare trap in this context, by contrast, refers to the barrier created by means-tested social grants that have in-built perverse incentives." The South African definition is typically used with regard to developing countries.

This concept may include other adverse effects of welfare such as on the family structure: it may encourage the increase in the numbers of single-mother families and divorce rates, as individuals see a distinct benefit in such a lifestyle.

In the UK, there is a distinction between two concepts within the welfare trap:

- The unemployment trap occurs when the net income difference between low-paid work and unemployment benefits is less than work-related costs (bus pass, work clothes, daycare), discouraging movement into work;

- The poverty trap is the position when means-tested benefit payments are reduced as income rises, combined with income tax and other deductions, with the effect of discouraging work with a higher income, longer hours or acquiring skills. In some cases, if a recipient's wage income rises too much, they may lose some or all of their social assistance.

Examples

If a person on welfare finds a part-time job that will pay the minimum wage of $5 per hour for eight hours per week (totaling $40), and, of the amount earned per week, $20 is deducted from welfare, there is a net gain of only $20. If the government imposes taxes on the $40, at say 15% ($6), and there may be extra child-care and commuting costs as well since that the person can no longer remain at home all day, the person is now worse off than before getting the job. This result occurs despite performing eight hours of work per week that is productive to society.

A welfare trap is an example of a perverse incentive. The welfare recipient, such as the one above, has an incentive to avoid raising productivity because the resulting income gain is not enough to compensate for the increased work effort.

An incentive to get out of the welfare trap is that the return to the labour market gives a person chances of moving up the career ladder, improving old and acquiring new job skills, etc., thus eventually improving standard of living. Policies that allow for the continued receipt of benefit payments for a period of time after entering work or up to a specific earnings ceiling may also eliminate the welfare trap. For example, for UK claimants of Incapacity Benefit or Employment Support Allowance, "permitted work" arrangements allow for paid work up to either 16 hours or £95 per week without the withdrawal of the disability benefit payments, leading to a net overall increase in income. However, any earnings over £20 may be taxed, and additional earnings may affect receipt of Housing Benefit and Council Tax Benefit, which is an example of the welfare trap remaining potentially in effect. To eliminate the welfare trap entirely would require a policy that permanently continues benefit payments regardless of any conditions, with no income from paid work being withdrawn. One example of this would be unconditional basic income.

See also

- Basic income

- Catch-22

- Criticisms of welfare

- Generational poverty

- Means test

- Negative income tax

- Poverty trap

- Welfare's effect on poverty

- Workfare

References

- Baetjer, Howard (August 24, 2016). "The Welfare Cliff and Why Many Low-Income Workers Will Never Overcome Poverty". Learn Liberty.

- An example of the use of "welfare" as shorthand for public assistance in an academic publication.

- "The Unemployment Trap", CentrePiece Spring 2008. Barbara Petrongolo, London School of Economics.

- Kay, Lawrence (August 18, 2009). "Escaping the Poverty Trap: How to help people on benefits into work". Policy Exchange.

- pdf, webpage, a SARPN (Southern African Regional Poverty Network) report

- "The state of working America, 1996-97". Lawrence Mishel, Jared Bernstein, John Schmitt, section "Government Benefits and Family structure: Is there a Welfare Trap?"

- "Gassing up the welfare trap machine", an Atlantic Institute for Market Studies webpage

- Brian Lee Crowley (June 8, 2005). "Equalization:Welfare Trap or Helping Hand, a Brian Lee Crowley speech". Archived from the original on September 29, 2011.

- DirectGov

- "Basic Income and Labor Supply: The German Case" by B. Michael Gilroy & Mark Schopf & Anastasia Semenova, 2012.