| Revision as of 17:04, 14 February 2007 edit164.58.20.50 (talk) →Ramifications of the controversy← Previous edit | Revision as of 17:05, 14 February 2007 edit undo164.58.20.50 (talk) →Theory vs. factNext edit → | ||

| Line 108: | Line 108: | ||

| Research into understanding these subjects is ongoing. | Research into understanding these subjects is ongoing. | ||

| ====Theory vs. fact==== | |||

| :''See also:'' '']'' and '']'' | |||

| {{main|Evolution as theory and fact}} | |||

| The argument that evolution is a ], not a fact, has often been made against the exclusive teaching of ].<ref>{{Harvnb|Johnson|1993|p=63}}, {{Harvnb|Tolson|2005}}, {{harvnb|Moran|1993}} ; ''. US District Court for the Northern District of Georgia (2005); Talk. Origins; Bill Moyers ''et al'', 2004. "." PBS. Accessed 2006-01-29. Interview with Richard Dawkins</ref> However, a large part of the difficulty is actually a linguistic problem and some confusion. scientist | |||

| ====Philosophical arguments==== | ====Philosophical arguments==== | ||

Revision as of 17:05, 14 February 2007

| Part of a series on | ||||

| Creationism | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| History | ||||

| Types | ||||

| Biblical cosmology | ||||

| Creation science | ||||

| Rejection of evolution by religious groups | ||||

| Religious views | ||||

|

||||

The creation-evolution controversy (also termed the creation vs. evolution debate or the origins debate) is a recurring dispute about the origins of the Earth, humanity, life, and the universe, a debate most prevalent in certain regions of the United States, where it is often portrayed as part of the culture wars.

While the controversy has a long history, today it primarily concerns what should be taught as science in schools, and what is good science. The teaching of biological evolution in the public schools is one significant area of contention, while the teaching of alternatives such as creation science and intelligent design are other aspects of the dispute.

In the first case, creationists argue that evolution should not be taught because it is bad science or because it is an anti-theist ideology dressed up as science. Although there has been some success in de-emphasizing evolution in some public schools by applying pressure to local school boards and even individual teachers, the teaching of evolution is still widespread. In the second case, concerned parents, educators, scientists, and other interested parties argue that creation science and intelligent design are pseudosciences as well as thinly disguised schemes to introduce religion to the classroom. In the United States, recent court decisions have affirmed this position, consistently thwarting the introduction of creation science and intelligent design into public science curricula.

History of the controversy

Main articles: History of creationism and History of evolutionary thoughtAntecedents to the controversy can be seen in the challenges made by various religious people and organizations to the legitimacy of certain scientific ideas since the Age of Enlightenment – for example, Galileo and his advocacy of "natural philosophy" in relation to the Inquisition of the Roman Catholic Church. Interpretation of the Judeo-Christian Bible had been the prerogative of a priesthood able to understand Latin, but printing of translations and wider literacy fostered by the Protestant Reformation led to more literal understandings of scripture.

Creation/evolution controversy in the age of Darwin

The Creation-Evolution controversy itself originated in Europe and North America in the late eighteenth century, when natural history categorised an enormous number of species, and traditional belief in Created kinds developed into a new idea that the original pair of every single species had been brought into existence by God at the Creation. Discoveries in geology led to various theories of an ancient earth, and fossils showing past extinctions prompted early ideas of evolutionism. Such ideas were particularly controversial in England where stability of both the natural world and the hierarchical social order were thought to be fixed by God's will. As the terrors of the French Revolution developed into war with France followed by economic depression threatening revolution, such subversive ideas were suppressed and associated with Radical agitators.

Conditions eased with economic recovery, and when Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation was published in 1844 its ideas of transmutation of species attracted wide public interest despite being attacked by the scientific establishment and many theologians who believed it to be in conflict with their interpretations of the biblical account of life's, especially humanity's, origin and development. However radical Quakers, Unitarians and Baptists welcomed the book's ideas of "natural law" supporting their struggle to overthrow the privileges of the Church of England.

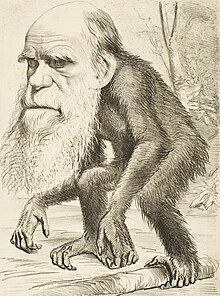

Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation remained a best-seller, and paved the way for widespread interest in the theory of natural selection as introduced and published by English naturalist Charles Darwin in his 1859 book, On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection. Darwin's book was praised by Unitarians as well as by liberal Anglican theologians whose Essays and Reviews sparked considerably more religious controversy in Britain than Darwin's publication, as its support of higher criticism questioned the historical accuracy of literal interpretations of the Bible and added declarations that miracles were irrational.

Darwin's book revolutionized the way naturalists viewed the world. The book and its promotion attracted attention and controversy, and many theologians reacted to Darwin's theories. For example, in his 1874 work What is Darwinism? the theologian Charles Hodge argued that Darwin's theories were tantamount to atheism. The controversy was fueled in part by one of Darwin's most vigorous promoters, Thomas Henry Huxley, who opined that Christianity is "a compound of some of the best and some of the worst elements of Paganism and Judaism, moulded in practice by the innate character of certain people of the Western World." Perhaps the most uncompromising of the evolutionary philosophers was the German, Ernst Heinrick Haeckel, a professor of biology, who dogmatically affirmed that nothing spiritual exists.

A watershed in the Protestant objections to evolution occured after about 1875. Previously, citing Louis Agassiz and other scientific luminaries, Protestant contributors to religious quarterlies dismissed Darwin's theories as unscientific. After 1875, it became clear that the majority of naturalists embraced evolution, and a sizable minority of these protestant contributors rejected Darwin's theory because it called into question the veracity of Scriptures.Cite error: A <ref> tag is missing the closing </ref> (see the help page).

The greatest concern for creationists at the turn of the twentieth century was the issue of human ancestry.

I do not wish to meddle with any man's family matters, or quarrel with any one about his relatives. If a man prefers to look for his kindred in the zoological gardens, it is no concern of mine; if he wants to believe that the founder of his family was an ape, a gorilla, a mud-turtle, or a moner, he may do so; but when he insists that I shall trace my lineage in that direction, I say No Sir!...I prefer that my genealogical table shall end as it now does, with "Cainan, which was the son of Seth, which was the son of Adam, which was the son of God."

Creationists during this period were largely premillennialists, whose belief in Christ's return depended on a quasi-literal reading of the Bible. However, they were not as concerned about geology, freely granting scientists any time they needed before the Edenic creation to account for scientific observations, such as fossils and geological findings. In the immediate post-Darwinian era, few scientists or clerics rejected the antiquity of the earth, the progressive nature of the fossil record. Likewise, few attached geological significance to the Bibilical flood, unlike subsequent creationists. Evolutionary skeptics, creationist leaders and skeptical scientists were usually either willing to adopt a figurative reading of the first chapter of Genesis, or allowed that the six days of creation were not necessarily 24-hour days.

Scopes trial

Main article: Scopes trialInitial reactions in the United States of America matched the developments in Britain, and when Wallace went there for a lecture tour in 1886–1887 his explanations of "Darwinism" were welcomed without any problems, but attitudes changed after the First World War. The controversy became political when public schools began teaching that man evolved from earlier forms of life per Darwin's theory of Natural Selection. In response, the State of Tennessee passed a law (the Butler Act of 1925) prohibiting the teaching of any theory of the origins of humans that contradicted the teachings of the Bible. This law was tested in the highly publicized Scopes Trial of 1925. The law was upheld by the Tennessee Supreme Court, and remained on the books until 1967 when it was repealed. However, the next year, 1968, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Epperson v. Arkansas 393 U.S. 97 (1968) that such bans contravened the Establishment Clause because their primary purpose was religious.

Biological Sciences Curriculum Study (BSCS) textbooks

By the mid-twentieth century, most neo-Darwinists either repudiated or dismissed earlier Lamarckian and theistic theories of evolution. Neo-darwinists including paleontologist George Simpson and Julian Huxley evangelized for Darwinism and urged that the public schools teach the "fact of evolution". Their desires were fulfilled in the 1960s, with the introduction of federally supported Biological Sciences Curriculum Study (BSCS) biology text books that promoted evolution as an organizing principle. Meanwhile, public opinion polls suggested that most Americans either believed that God specially created human beings or guided evolution. Membership in churches favoring increasingly literal interpretations of Scripture continued to rise, with the Southern Baptist Convention and Luthern Church–Missouri Synod outpacing all other denominations. With growth, these churches became better equipped to carry a creationist message, with their own colleges, schools, publishing houses, and broadcast media.

With decreasing church membership among evolutionary scientists, the role of opposing the anti-BSCS textbook movement passed from prominent scientists in liberal churches to secular scientists less equipped to reach Christian audiences. Anti-evolutionary forces were able to reduce the number of school districts utilizing BSCS biology text books, but courts continued to prevent religious instruction in public schools.

ICR and the co-opting of the creationist label

Main article: Institute for Creation ResearchHenry M. Morris and John C. Whitcomb Jr.'s influential The Genesis Flood argued that creation was literally 6 days long, humans lived concurrently with dinosaurs, and that God created each kind of life, was published in 1961. With publication, Morris became a popular speaker, spreading anti-evolutionary ideas at fundamentalist churches, colleges, and conferences. Morris setup up the Creation Science Research Center (CSRC), an organization dominated by baptists, as an adjuct to the Christian Heritage College. The CSRC rushed publication of biology text books that promoted creationism, and also published other books such as Kelly Segrave's sensational Sons of God Return that dealt with UFOlogy, flood geology, and demonology. These efforts were against the recommendations of Morris, who urged a more cautious and scientific approach. Ultimately, the CSRC broke up, and Morris founded the Institute for Creation Research. Morris promised that the ICR, unlike the CSRC, would be controlled and operated by scientists.. During this time, Morris and others who supported flood geology adopted the scientific sounding terms scientific creationism and creation science. The flood geologists effectively co-opted "the generic creationist label for their hyperliteralist views". Previously, Creationism was a generic term describing a philosophical perspective that presupposes the existence of a supernatural creator..

Controversy in recent times

The controversy continues to this day, with the mainstream scientific consensus on the origins and evolution of life actively attacked by creationist organizations and religious groups who desire to uphold some form of creationism (usually young earth creationism, creation science, old earth creationism or intelligent design) as an alternative. Most of these groups are explicitly Christian, and more than one sees the debate as part of the Christian mandate to evangelize. Some see science and religion as being diametrically opposed views which cannot be reconciled (see section on the false dichotomy). More accommodating viewpoints, held by mainstream churches and many scientists, consider science and religion to be separate categories of thought, which ask fundamentally different questions about reality and posit different avenues for investigating it.

More recently, the Intelligent Design movement has taken an anti-evolution position which avoids any direct appeal to religion. However, Leonard Krishtalka, a paleontologist and an opponent of the movement, has called intelligent design "nothing more than creationism in a cheap tuxedo", and, in Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District (2005) United States District Judge John E. Jones III ruled that intelligent design is not science, but is grounded in theology and cannot uncouple itself from its creationist, and thus religious, antecedents. Before the trial began, President Bush commented endorsing the teaching of Intelligent design alongside evolution "I felt like both sides ought to be properly taught ... so people can understand what the debate is about." Scientists argue that Intelligent design does not represent any research program within the mainstream scientific community, and is opposed by most of the same groups who oppose creationism.

Evolutionary opponents defining evolution

Evolution is sometimes expanded by creationists to include such things as the origins of life from matter, the Big Bang Theory, and the formation of stars. For example, Kent Hovind defines evolution to include the creation of time, space, matter, the creation of planets and stars from dust, spontaneous generation of life from matter, the creation of reproduction in life forms, and major changes of life forms such as speciation. However, although the word evolution is used as part of several astronomical terms such as stellar evolution, none of these are implied by the term evolution alone.

Common venues for debate

Conflict occurs mostly in the public arena.

Books and articles targeting the mainstream public have been published on both sides of the issue. For example, Creationists publish works intended to cast doubts about evolution, and biological scientists and similiarly minded individuals publish works casting doubts about creationism. These publications, and numerous public debates have been sponsored by churches, universities, and scientific clubs.

Debate on the Internet

With the rise of the Internet, the battle between antagonists has also been waged on-line. One of the first Usenet newsgroups, Talk.origins, was created in 1986, and became a hotbed for debating the controversy. Since then, the Talk.origins newsgroup has been a forum for sundry discussions of nearly every topic and issue ever conceived on both sides of the controversy.

In 1994 FAQs from the Talk.origins newsgroup were put together into TalkOrigins Archive, which has since developed as a website resource presenting mainstream science perspectives on the various antievolution claims made by Creationists. Subsequently, Creationists' websites followed suit with their own clearinghouses, the most famous of which are Ken Ham's Answers in Genesis and the Institute for Creation Research website. Chatrooms, message boards, and blogs continue on both sides of the controversy to promote their views with many arguments printed and reprinted.

Differing religious positions

A wide spectrum of beliefs, mostly associated with the Abrahamic religions, have been categorized into broad types of creationism.

Almost all churches teach that God created the cosmos. Most contemporary Christian leaders and scholars from many mainstream churches, such as Roman Catholic, Anglican and some Lutheran denominations, reject reading the Bible as though it could shed light on th

Conflicts inherent to the controversy

While debate on the details of scientific theories and their philosophical or religious implications are often the most intense parts of the controversy, some participants on both sides believe that the conflict boils down to opposing definitions of all or parts of science, reality, and religion. Accusations of misleading formulations, incorrect or false statements, and inappropriate mixing of ideas are also fundamental points of disagreement.

The Level of support for evolution is overwhelming in the scientific community and academia, while support for creation based alternatives is minimal among secular scientists.

Accusations involving science

Many creationists vehemently oppose certain scientific theories in a number of ways, including opposition to specific applications of scientific processes, accusations of bias within the scientific community, and claims that discussions within the scientific community reveal or imply a crisis. In response to perceived crises in modern science, creationists claim to have an alternative, typically based on faith, "creation science," and/or intelligent design. Opponents of creationism spend much of their participation in the controversy defending against these accusations. Some of the more common creationist claims involving science are listed below, together with their associated debates.

Limitations of the scientific endeavor

Creationists who use the controversy as an opportunity for apologetics and evangelism will often refer to scientific theories as being incomplete, incorrect, or inherently flawed due to the infinite regression nature of questions of origins. Typical of these challenges are the somewhat rhetorical questions asked by creationists "What caused the Big Bang?" or "What was the nature of the first lifeform?" These questions are in principle subject to scientific investigation, but if and when answers are provided it is likely that the answers will themselves be subject to similar kinds of regressive inquiry. These first cause arguments are invoked as a means to point to the existence of a deity (and often, in particular, the Judeo-Christian God). Creationists argue that science cannot supply such answers, and that their religious discourse is more complete, more reliable, and surpasses the naturalistic descriptions that science provides. However, these same infinite regression problems are just as problematic when applied to a supreme being.

Science is indeed limited in its inquiry of causes, as the scientific method yields descriptive explanations rather than explaining why nature exists in such a way, and is generally limited to the independently observable evidence. However such critiques of the limits of science and rational inquiry in general have no single philosophical resolution and are often seen as problems for theistic claims as well. The pronouncement by creationists that such limitations point to the existence of a creator god is criticized by many skeptics as a God of the gaps argument where religious argumentation is reduced to a placeholder for gaps in human knowledge.

Dawkins goes further. In chapter 4 of The God Delusion, Why there almost certainly is no God, he says that evolution by natural selection can be used to demonstrate that the argument from design is wrong. He argues that a hypothetical cosmic designer would require an even greater explanation than the phenomena s/he/it was intended to explain, and that any theory that explains the existence of the universe must be a “crane”, something equivalent to natural selection, rather than a “skyhook” that merely postpones the problem. Dawkins holds out hope for a cosmological equivalent to Darwinism that would explain why the universe exists in all its amazing complexity. He uses the argument from improbability, for which he introduced the term "Ultimate Boeing 747 gambit", to argue that "God almost certainly does not exist":

However statistically improbable the entity you seek to explain by invoking a designer, the designer himself has got to be at least as improbable. God is the Ultimate Boeing 747.

The "Boeing 747" reference alludes to a statement reportedly made by Fred Hoyle arguing in favor of panspermia: the "probability of life originating on earth is no greater than the chance that a hurricane sweeping through a scrap-yard would have the luck to assemble a Boeing 747." Dawkins objects to this argument on the grounds that it is made "...by somebody who doesn't understand the first thing about natural selection". A common theme in Dawkins' books is that natural selection, not chance, is responsible for the evolution of life, and that the apparent improbability of life's complexity does not imply evidence of design or a designer. He goes further in this chapter by presenting examples of apparent design. Dawkins concludes the chapter by arguing that his "Ultimate 747" gambit is a very serious argument against the existence of God, and that he has yet to hear "a theologian give a convincing answer despite numerous opportunities and invitations to do so." Dawkins quotes Dan Dennett, where Dennett calls Dawkins' retort "an unrebuttable refutation" dating back two centuries.

Conversely, mathematicians and scientists have found that the capabilities of evolution through selection can often surpass the capabilities of (human) intelligent designers. There has been some recent success in implementing simulated evolution for artificial uses, including genetic algorithms, which can find the solution to a multi-dimensional problem more quickly than standard software produced by humans, and the use of evolutionary fitness landscapes to optimize the design of a system. Evolutionary optimization techniques are particularly useful in situations in which it is easy to determine the quality of a single solution, but hard to go through all possible solutions one by one.

Examples of open questions in origins research within their associated scientific fields include:

- Cosmogony as the speculative predecessor to the explanations provided by physical cosmology and the Big Bang.

- The nebular hypothesis as a consistent application of the observations of protoplanetary discs and general principles of planetary science.

- The giant impact hypothesis as a consistent model for lunar formation in conjunction with the geological timescale.

- The various scientific inquiries into the origin of life including consistent models of abiogenesis.

Research into understanding these subjects is ongoing.

Philosophical arguments

Critiques such as those based on the distinction between theory and fact are often leveled against unifying concepts within scientific disciplines. For example, uniformitarianism, Occam's Razor/parsimony, and the Copernican principle are claimed to be the result of a bias within science toward philosophical naturalism, which is equated by many creationists to atheism. In countering this claim, philosophers of science use the term methodological naturalism to refer to the long standing convention in science of the scientific method which makes the methodological assumption that observable events in nature are explained only by natural causes, without assuming the existence or non-existence of the supernatural, and so considers supernatural explanations for such events to be outside science. Creationists claim that supernatural explanations should not be excluded and that scientific work is paradigmatically close-minded.

Because modern science tries to rely on the minimization of a priori assumptions, error, and subjectivity, as well as on avoidance of Baconian idols, it remains neutral on subjective subjects such as religion or morality. Mainstream proponents accuse the creationists of conflating the two in a form of pseudoscience.

Falsifiability

In what one sociologist derisively called "Popper-chopping," creation scientists found a reluctant hero in Science Philosopher Karl R. Popper. The concept of Falsifiability, coined in Popper's book, The Logic of Scientific Discovery, led Popper to classify Darwinism as a "metaphysical research programme." The falsifiability principle essentially states that scientific theories are testable, and theories that are not testable are not scientific. Evolutionary opponents wielded Popper's critique as a double-edged sword both to disqualify evolution as science, and to argue that creation science is an equally valid metaphysical research program. For example, Duane Gish, a leading Creationist proponent, wrote in a letter to Discover magazine (July 1981): "Stephen Jay Gould states that creationists claim creation is a scientific theory. This is a false accusation. Creationists have repeatedly stated that neither creation nor evolution is a scientific theory (and each is equally religious)."

Popper responded to news that his conclusions were being used by anti-evolutionary forces by affirming that theories regarding the origins of life on earth were scientific because "their hypotheses can in many cases be tested." Creation scientists noted that Popper's statement stopped short of granting full scientific standing to Darwinism, and continued to argue that evolutionary origins failed to meet the falsifiability criteria.

Debate among some scientists and philosophers of science on the applicability of falsifiability in science continues. Even so, renowned Biologist and prominent creationism critic Richard Dawkins responds to claims that evolution is not falsifiable by pointing out evolution "is a theory of gradual, incremental change over millions of years ... If there were a single hippo or rabbit in the Precambrian, that would completely blow evolution out of the water." Similarly, according to a Time Magazine article, Dawkins also quotes evolutionary biologist J.B.S. Haldane's example: "fossil rabbits in the Precambrian era" would falsify evolution; therefore, evolution is falsifiable.

In his 1982 decision McLean v. Arkansas Board of Education, Judge William R. Overton used falsifiability as one basis in his ruling against the teaching of creation science in the public schools, ultimately declaring that Creation Science "is simply not science."

Arguments against evolution

Creationists have criticized the scientific evidence used to support evolution as being based on faulty assumptions, unjustified jumping to conclusions, or even outright lies.Cite error: A <ref> tag is missing the closing </ref> (see the help page). However, almost universally these have been shown to be quote mines (lists of out of context or misleading quotations) that do not accurately reflect the evidence for evolution or the mainstream scientific community's opinion of it, or highly out-of-date. Many of the same quotes used by creationists have appeared so frequently in Internet discussions due to the availability of cut and paste functions, that the TalkOrigins Archive has created "The Quote Mine Project" for quick reference to the original context of these quotations.

Conflation of science and religion

While the controversy is usually portrayed in the mass media as being between creationists and scientists, in particular evolutionary biologists in fact very few scientists consider the debate to have any academic legitimacy. Many of the most vocal creationists rely heavily on their criticisms of modern science, philosophy, and culture as a means of Christian apologetics. For example, as a way of justifying the struggle against "evolution", one prominent creationist has declared "the Lord has not just called us to knock down evolution, but to help in restoring the foundation of the gospel in our society. We believe that if the churches took up the tool of Creation Evangelism in society, not only would we see a stemming of the tide of humanistic philosophy, but we would also see the seeds of revival sown in a culture which is becoming increasingly more pagan each day."

Religion and historical scientists

| This Creation-evolution controversy section called Religion and historical scientists does not cite any sources. Please help improve this Creation-evolution controversy section called Religion and historical scientists by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Rejection of evolution by religious groups" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (December 2006) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Creationists often butress their arguments arguing that Christianity and belief in a literal Bible are either foundationally significant or directly responsible for scientific progress. To that end, Institute for Creation Research founder Henry M. Morris has enumerated scientists such as astronomer and philosopher Galileo, mathematician and theoretical physicist James Clerk Maxwell, mathematician and philosopher Blaise Pascal, geneticist monk Gregor Mendel, and arguably the greatest figure in the history of science, Isaac Newton as believers in a biblical creation narrative.

Since most of the scientists creationists tend to list as supporters were not aware of evolution because they were either no longer alive when it was proposed or the idea was outside their field of study, this kind of argument is generally rejected as being specious by those who oppose creationism.

In many cases, the context for the scientist in question opposing evolution was historically situated differently than it would be today, and usually involved early work on the mechanisms of evolution. Though biological evolution of some sort became the primary mode of discussing speciation within science since the late 19th century, it was not until the mid-20th century that evolutionary theories stabilized into the modern synthesis. Some of the historical scientists marshalled by creationists were dealing with quite different issues than any are engaged with today: Louis Pasteur, for example, opposed the theory of spontaneous generation with biogenesis, an advocacy which some creationists describe as a critique on chemical evolution and abiogenesis. Pasteur also accepted that some form of evolution had occurred and that the Earth was millions of years old.

The relationship between science and religion was not portrayed in antagonistic terms until the late-19th century, and even then there have been many examples of the two being reconcileable for evolutionary scientists. Many historical scientists wrote books explaining how pursuit of science was seen by them as fulfillment of spiritual duty in line with their religious beliefs. Even so, such professions of faith were not insurance against dogmatic opposition by certain religious people.

Some extensions to the creationist argument have included suggesting that Einstein's deism was a tacit endorsement of creationism and incorrectly suggesting that Charles Darwin converted on his deathbed and recanted evolutionary theory.

Science as religion

A popular accusation among creationists is that evolution is itself a religion based on secular humanism, scientific materialism, or philosophical naturalism.

Creationists and their supporters use neologisms such as evolutionism and Darwinism to refer to the modern theory of evolution, and evolutionists and Darwinists to those who accept it, often pejoritively. In the context of the evolution/creation controversy, many evolution proponents object to such usage as inaccurate and misleading. In particular, the -ist/-ists/-ism suffixes evoke similarity to religious or philosophical rather than scientific ideas (e.g. creationist, fundamentalist, Calvinist, Communist). It is claimed that in the case of evolutionism the label implies that evolution is a belief system akin to religion, while in the case of Darwinism, the implication is that modern evolutionary theory is the static work of just one individual, Charles Darwin, as though he were not a scientist but rather the founder of a religious sect. However, these terms are also commonly used without pejorative intent by others, including historians, commentators, and sometimes scientists, e.g., scientist, evolutionist, Neo-Darwinism, etc.

False dichotomy

Many supporters of evolution (especially religious ones) disagree with the claim made by creationists and some evolutionists that there exists an inherent, irresolvable conflict between religion and evolutionary theory. Since many, if not most religious people do accept evolution (see Theistic evolution), they argue that this is a false dichotomy. Views on this subject cover a very wide spectrum, from strict Biblical literalism (which implies Young Earth creationism) to atheism.

Strict (Intelligent Design, Old Earth, and Young Earth) creationists strenuously reject evolutionary creationism on two grounds:

- Strict creationists claim that "evolution" is an attempt to remove God from the natural world. "Evolution as understood by its ablest advocates is an inherently atheistic explanation," claims one. Such creationists claim that, because probability, chance, and randomness are used as explanations for mutations and genetic drift, God is necessarily excluded from the mechanisms of evolution. Creationists who are actively involved in the conflict tend to criticize those who advocate theistic evolution as having missed a claimed fundamental disparity between the naturalistic mechanisms described as explanations for the natural sciences and the theistic action inherent to the doctrine of creation.

- Strict creationists claim that there are two and only two positions that can possibly be correct: creation science (or intelligent design) and the scientific mainstream (evolution). This automatically precludes discussions of other origin beliefs and allows such advocates to claim that the only plausible explanation of origins that permits God is that which they are advocating. On this basis they claim that science itself is inherently atheistic, and lobby for a reversion to faith based natural philosophy.

A point concerning this apparent Dichotomy is provided by some Christian apologists, notably Stanley Jaki and Cardinal Ratzinger (now Pope Benedict XVI), that God in his omnipotence, is fully capable of creating a universe which would bring forth the desired result - that is, humanity - as a consequence of the Laws of Creation inherent in it. Also, the literal view of creationism therefore propounds a "small" view of God's greatness. They qualify this theory with the assumption that after evolution brought forth the biology of humans, God breathed the Spirit into them to give them Life in His image. Furthermore they promote the idea that there is no contradiction between the biblical account of creation and the latest scientific understanding.

"Science does not produce evidence against God. Science and religion ask different questions," according Martin Nowak, a self-described person of faith as well as a professor of mathematics and evolutionary biology at Harvard. The Archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams, the leader of the world's Anglicans, comes to a similar conclusion, albeit from a completely different perspective. In March 2006, he stated his discomfort about teaching creationism, saying that creationism was "a kind of category mistake, as if the Bible were a theory like other theories." He also said: "My worry is creationism can end up reducing the doctrine of creation rather than enhancing it."

Ramifications of the controversy

Public education in the United States

| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Rejection of evolution by religious groups" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (zhjbv;kjhn haye hey you guys hows it hangin January 2007) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Evolution and creationism 07.</ref>

Citations

- See Hovind 2006 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFHovind2006 (help), for example.

- Larson 2004, p. 247-263 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFLarson2004 (help) Chapter titled Modern Culture Wars. See also Ruse 1999, p. 26 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFRuse1999 (help), who writes "One thing that historians delighted in showing is that, contrary to the usually held tale of science and religion being always opposed...religion and theologically inclined philosophy have frequently been very significant factors in the forward movement of science."

- Numbers 1992, p. 3-240 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFNumbers1992 (help)

- ^ Peters & Hewlett 2005, p. 1 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFPetersHewlett2005 (help)

- Hayward 1998, p. 2 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFHayward1998 (help)

- Peters & Hewlett 2005, p. 5 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFPetersHewlett2005 (help)

- ^ Moore 2006 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFMoore2006 (help)

- Desmond & Moore 1991, p. 34-35 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFDesmondMoore1991 (help)

- van Wyhe 2006 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFvan_Wyhe2006 (help).

- Desmond & Moore 1991, p. 321-322 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFDesmondMoore1991 (help).

- Desmond & Moore 1991, p. 500-501 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFDesmondMoore1991 (help).

- Hodge 1874, p. 177 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFHodge1874 (help), Numbers 1992, p. 14 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFNumbers1992 (help)

- Burns, Ralph, Lerner, & Standish 1982, p. 965 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFBurnsRalphLernerStandish1982 (help), Huxley 1902 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFHuxley1902 (help)

- Burns, Ralph, Lerner, & Standish 1982, p. 965 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFBurnsRalphLernerStandish1982 (help)

- ^ Numbers 1992, p. 13 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFNumbers1992 (help)

- Numbers 1992, p. 15 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFNumbers1992 (help)

- Numbers 1992, p. 15 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFNumbers1992 (help), quoting H.L Hastings' tract in Was Moses Mistaken? or, Creation and Evolution (1896)

- Numbers 1992, p. 14 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFNumbers1992 (help)

- Numbers 1992, p. 14-15 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFNumbers1992 (help)

- ^ Numbers 1992, p. 17 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFNumbers1992 (help)

- Numbers 1992, p. 18 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFNumbers1992 (help), Noting that this applies to published or public skeptics. Many or most christians may have held on to a literal six days of creation, but these views were rarely expressed in books and journals. Exceptions are also noted, such as literal interpretations published by Eleazar Lord (1788-1871) and David Nevins Lord (1792-1880). However, the observation that evolutionary critics had a relaxed interpretation of Genesis is supported by specifically enumerating: Louis Agassiz (1807-1873); Arnold Henry Guyot (1807-1884); John William Dawson (1820-1899); Enoch Fitch Burr (1818-1907); George D. Armstrong (1813-1899); Charles Hodge, theologian (1797-1878); James Dwight Dana (1813-1895); Edward Hitchcock, clergyman and respected Amherst College geologist, (1793-1864); Reverend Herbert W. Morris (1818-1897); H. L. Hastings (1833?-1899); Luther T. Townsend (1838-1922); Alexander Patterson, Presbyterian evangelist who published The Other Side of Evolution Its Effects and Fallacy

- ^ Larson 2004, p. 253 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFLarson2004 (help)

- Larson 2004, p. 248,250 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFLarson2004 (help)

- ^ Larson 2004, p. 246,252 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFLarson2004 (help)

- ^ Larson 2004, p. 251 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFLarson2004 (help)

- Larson 2004, p. 255 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFLarson2004 (help),Numbers 1992, p. xi,200-208 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFNumbers1992 (help)

- Larson 2004, p. 255 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFLarson2004 (help)

- Numbers 1992, p. 284 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFNumbers1992 (help)

- Numbers 1992, p. 284-285 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFNumbers1992 (help)

- Numbers 1992, p. 284 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFNumbers1992 (help)

- Numbers 1992, p. 286 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFNumbers1992 (help)

- Quoting Larson 2004, p. 255-256 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFLarson2004 (help): "Fundamentalists no longer merely denounced Darwinism as false; they offered a scientific-sounding alternative of their own, which they called either 'scientific creationism (as distinct from religious creationism) or 'creation science' (as opposed to evolution science."

- Larson 2004, p. 254-255 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFLarson2004 (help), Numbers 1998, p. 5-6 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFNumbers1998 (help)

- Hayward 1998, p. 11 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFHayward1998 (help)

- Verderame 2007 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFVerderame2007 (help),Simon 2006 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFSimon2006 (help)

- Dewey 1994, p. 31 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFDewey1994 (help), and Wiker 2003 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFWiker2003 (help), summarizing Gould.

- As reported in the 4 May 2005 edition of the Washington Post

- Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District, Case No. 04cv2688. December 20 2005, Ruling Whether ID Is Science: Page 89, and Conclusion.

- Bumiller 2005 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFBumiller2005 (help), Peters & Hewlett 2005, p. 3 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFPetersHewlett2005 (help)

- Larson 2004, p. 258 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFLarson2004 (help) "Virtually no secular scientists accepted the doctrines of creation science; but that did not deter creation scientists from advancing scientific arguments for their position." See also Martz & McDaniel 1987, p. 23 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFMartzMcDaniel1987 (help), a Newsweek article which states "By one count there are some 700 scientists (out of a total of 480,000 U.S. earth and life scientists) who give credence to creation-science, the general theory that complex life forms did not evolve but appeared 'abruptly'."

- Faid 1991 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFFaid1991 (help) as summarized by Hayward 1998, p. 87 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFHayward1998 (help). Robert W. Faid, a nuclear power consultant and Ig Nobel Prize prize winner, is critical of the Big Bang and the "evolutionary origins of genus". Also, Corey 1995 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFCorey1995 (help) as summarized by Hayward 1998, p. 87 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFHayward1998 (help), in which the Big Bang is treated as part of evolution and creation. However, see Hayward 1998, p. 79 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFHayward1998 (help), summarizing Aviezer 1990 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFAviezer1990 (help) in which Nathan Aviezer, a professor of physics at Bar-Ilan University in Tel Aviv argues that each of the 6 days of creation is equal to 2.5 Billion years, and that Ge 1:3 refers to the Big Bang. See also Hayward 1998, p. 86-87 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFHayward1998 (help), summarizing CSIE 1986 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFCSIE1986 (help) in which a group of scientists who are Christians support the Big Bang but questions other aspects of modern evolutionary theory.

- Hovind 2006 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFHovind2006 (help)

- One such expansion is rebutted here

- Scott 2000 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFScott2000 (help)

- Ghedotti 2006 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFGhedotti2006 (help)

- Myers 2006 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFMyers2006 (help); NSTA 2003 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFNSTA2003 (help); IAP 2006 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFIAP2006 (help); AAAS 2006 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFAAAS2006 (help); and Pinholster 2006 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFPinholster2006 (help)

- Larson 2004, p. 258 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFLarson2004 (help) "Virtually no secular scientists accepted the doctrines of creation science; but that did not deter creation scientists from advancing scientific arguments for their position." See also Martz & McDaniel 1987, p. 23 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFMartzMcDaniel1987 (help), a Newsweek article which states "By one count there are some 700 scientists (out of a total of 480,000 U.S. earth and life scientists) who give credence to creation-science, the general theory that complex life forms did not evolve but appeared 'abruptly'."

- Johnson 1993, p. 69 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFJohnson1993 (help) where Johnson cites three pages spent in Issac Asimov's New Guide to Science that take creationists to task, while only spending one half page on evidence of evolution.

- Winston 2006 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFWinston2006 (help)

- Dawkins 2006, p. 114 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFDawkins2006 (help)

- Dawkins 2006, p. 113 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFDawkins2006 (help)

- Dawkins 2006, p. 157 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFDawkins2006 (help)

- Dawkins 2006, p. 157 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFDawkins2006 (help), referring to Dennett 1995, p. 155 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFDennett1995 (help). The Dennett citation praises Dawkins: "Dawkins' retort to the theorist who would call on God to jump-start the evolution process is an unrebuttable refutation, as devastating today as when Philo used it to trounce Cleanthes in Hume's Dialogues two centuries earlier." Dialogues concerning Natural Religion is a fictional/philosophical work.

- Interferometric "fitness" and the large optical array, Dr David Buscher and Prof. Chris Haniff, 2003 -- optimizing the design of a large interferometer array using an evolutionary fitness landscape.

- Johnson 1998 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFJohnson1998 (help), Hodge 1874, p. 177 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFHodge1874 (help), Wiker 2003 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFWiker2003 (help), Peters & Hewlett 2005, p. 5 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFPetersHewlett2005 (help)--Peters and Hewlett argue that the atheism of many evolutionary supporters must be removed from the debate

- Lenski 2000, p. Conclusions harvnb error: no target: CITEREFLenski2000 (help)

- Johnson 1998 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFJohnson1998 (help)

- Einstein 1930, p. 1-4 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFEinstein1930 (help)

- Dawkins 1997 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFDawkins1997 (help)

- Unknown sociologist quoted in Numbers 1992, p. 247 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFNumbers1992 (help)

- Numbers 1992, p. 246 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFNumbers1992 (help)

- Popper 1976, p. 167-180 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFPopper1976 (help) as quoted by Number 1992, p. 247 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFNumber1992 (help)

- Kofahl 1989 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFKofahl1989 (help) as quoted by Numbers 1992, p. 247 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFNumbers1992 (help)

- Lewin 1982 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFLewin1982 (help)

- Popper 1980, p. 611 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFPopper1980 (help) as cited in Numbers, 1992 & p247 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFNumbers1992p247 (help)

- Numbers 1992, p. 247 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFNumbers1992 (help)

- Ruse 1999, p. 13-37 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFRuse1999 (help), which discusses conflicting ideas about science among Karl Popper, Thomas Samuel Kuhn, and their disciples.

- As quoted by Wallis 2005, p. 32 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFWallis2005 (help). Also see Dawkins 1986 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFDawkins1986 (help) and Dawkins 1995 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFDawkins1995 (help)

- Wallis 2005, p. 6 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFWallis2005 (help) paraphrase of Dawkins quoting Haldane

- Dorman 1996 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFDorman1996 (help)

- ^ Pieret 2006 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFPieret2006 (help)

- TalkOrigins comment; Articles on the Panda's Thumb about quote mines, PZ Myers briefly comments on a famous quote mining of Darwin, etc.

- Myers 2006 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFMyers2006 (help)

- IAP 2006 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFIAP2006 (help),AAAS 2006 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFAAAS2006 (help)

- Ham, Ken. Creation Evangelism (Part II of Relevance of Creation). Creation Magazine 6(2):17, November 1983. http://www.answersingenesis.org/creation/v6/i2/creationII.asp

- Woods 2005, p. 67-114 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFWoods2005 (help), Chapter Five: The Church and Science

- Morris 1982 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFMorris1982 (help)

- Wiker 2003 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFWiker2003 (help), Johnson 1993, p. 125-134 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFJohnson1993 (help)

- For example, Ruse 1999, p. 55-80 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFRuse1999 (help), Burns, Ralph, Lerner, & Standish 1982, p. 962-965 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFBurnsRalphLernerStandish1982 (help)

- Peters & Hewlett 2005, p. 2 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFPetersHewlett2005 (help)

- Woodmorappe, John. 1999. New Educational Activities for Home Schooling Science: A Hands-on Science Activity that Demonstrates the Atheism and Nihilism of Evolution. http://www.rae.org/nihilism.html

- Wallis 2005, p. 3 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFWallis2005 (help)

- Williams 2006 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFWilliams2006 (help)

References

- Template:Harvard reference Retrieved on 2007-01-14

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard referenceRetrieved on 2007-01-22

- Template:Harvard reference Retrieved on 2007-01-14

- Template:Harvard reference Retrieved on 2007-01-14

- Template:Harvard reference Retrieved on 2007-02-03

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference on-line link to condensed version retrieved on 2007-02-02

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference Retrieved on 2007-01-30

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference Retrieved on 2007-01-14

- Template:Harvard reference Retrieved on 2007-01-31

- Template:Harvard reference Retrieved on 2007-01-30

- Template:Harvard reference Retrieved on 2007-01-29

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference Retrieved on 2007-01-14

- Template:Harvard reference Retrieved on 2007-02-05

- Template:Harvard reference Retrieved on 2007-01-17

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard referenceRetrieved on 2007-01-20

- Template:Harvard reference Retrieved on 2007-01-14

- Template:Harvard reference Retrieved on 2007-01-17

- Template:Harvard reference Retrieved on 2007-01-14

- Template:Harvard reference Retrieved on 2007-01-16

- Template:Harvard reference Retrieved on 2007-01-14

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference See abstract Retrieved on 2007-01-29

- Template:Harvard reference Retrieved on 2007-01-14

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference Retrieved on 2007-01-23

- Template:Harvard reference Retrieved on 2007-01-14 This is a reproduction of a Science article on Robert L. Hall's faculty pages. It quotes a Discover letter to the editor by David Gish responding to Stephen Jay Gould's description of creation science.

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference Retrieved on 2007-02-07

- Template:Harvard reference Retrieved on 2007-01-24

- Template:Harvard reference Retrieved on 2007-01-23

- Template:Harvard reference Retrieved on 2007-01-20

- Template:Harvard reference Retrieved on 2007-01-20

- Template:Harvard reference Retrieved on 2006-11-18

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference Retrieved on 2007-01-14

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference Retrieved on 2007-01-28

- Template:Harvard reference Retrieved on 2007-01-23

- Template:Harvard reference Retrieved on 2007-01-14

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard referenceRetrieved on 2007-01-22

- Template:Harvard reference As reprinted at talkorigins.org Retrieved on 2007-01-23

- Template:Harvard reference Retrieved on 2007-02-01

- Template:Harvard reference Retrieved on 2007-02-03

- Template:Harvard reference Retrieved on 2007-01-17

- Template:Harvard reference Retrieved on 2007-01-14

- Template:Harvard reference Retrieved on 2007-01-6

- Template:Harvard reference Retrieved on 2007-01-17

- Template:Harvard reference Retrieved on 2007-01-24

- Template:Harvard reference Retrieved on 2007-02-07

- Template:Harvard reference Retrieved on 2007-01-31

- Template:Harvard reference Retrieved on 2007-01-21

- Template:Harvard reference Retrieved on 2007-01-14

- Template:Harvard referenceRetrieved on 2007-01-22

- Template:Harvard reference Retrieved on 2007-15-01

- Template:Harvard reference

Published books and other resources

- Burian, RM: 1994. Dobzhansky on Evolutionary Dynamics: Some Questions about His Russian Background. In The Evolution of Theodosius Dobzhansky, ed. MB Adams, Princeton University Press.

- Samuel Butler, Evolution Old and New, 1879, p. 54.

- Darwin, "Origin of Species," New York: Modern Library, 1998.

- Dobzhansky, Th: 1937. Genetics and the Origin of Species, Columbia University Press

- Henig, The Monk in the Garden: The Lost and Found Genius of Gregor Mendel, the Father of Genetics, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2000.

- Kutschera, Ulrich and Karl J. Niklas. 2004. "The modern theory of biological evolution: an expanded synthesis." Naturwissenschaften 91, pp. 255-276.

- Mayr, E. The Growth of Biological Thought, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass., 1982.

- James B. Miller (Ed.): An Evolving Dialogue: Theological and Scientific Perspectives on Evolution, ISBN 1-56338-349-7

- Morris, H.R. 1963. The Twilight of Evolution, Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House.

- Numbers, R.L. 1991. The Creationists: The Evolution of Scientific Creationism, Berkely: University of California Press.

- Pennock, Robert T. 2003. "Creationism and intelligent design." Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics 4, pp. 143-163.

- Carl Sagan. The Demon-Haunted World. New York: Ballantine Books, 1996.

- Scott, Eugenie C. 1997. "Antievolution and creationism in the United States." Annual Review of Anthropology 26: 263-289.

- Maynard Smith, "The status of neo-darwinism," in "Towards a Theoretical Biology" (C.H. Waddington, ed., University Press, Edinburgh, 1969.

- D.L. Hull: The Use and Abuse of Sir Karl Popper. Biology and Philosophy 14:4 (October 1999), 481–504.

- Strobel, Lee. 2004. The Case for a Creator. Grand Rapids: Zondervan.

See also

- Articles related to the creation-evolution controversy

- History of the creation-evolution controversy

- Level of support for evolution

- List of participants in the creation-evolution controversy

- Allegorical interpretations of Genesis

- Anti-intellectualism

- Creationism

- Creation science

- Evidence of evolution

- Evolution

- Intelligent design

- Lysenkoism

- Natural theology

- Project Steve

- Teach the Controversy

- Clergy Letter Project

- Evolution Sunday

External links

Comments on Creationism as Social Policy

Theistic Evolution (a mixture of religious belief and science)

Examples of Creationist Beliefs

- An Index to Creationist Claims - attempts to maintain a complete list of creationist claims leveled against evolution, with rebuttals and references from the scientific community

Young Earth Creationists

- Answers in Genesis

- Creation Ministries International A splinter group from Answers in Genesis including most of their non-US chapters.

Old Earth Creationists

- Answers In Creation Old Earth Creationists site

- Reasons to Believe - Offering a biblically based old-earth creation model

In the News

- So what's with all the dinosaurs? A museum dedicated to the idea that the creation of the world, as told in Genesis, is factually correct - will soon open. The Guardian (UK) 13 November 2006: G2 section pp.12-13.

Formal debates

- Kenneth R. Miller vs. Phillip E. Johnson (Nova online, 1996)

- The 1997 Firing Line Creation-Evolution Debate featuring Kenneth R. Miller, Michael Ruse, Eugenie Scott, Barry Lynn (evolution) vs. Phillip E. Johnson, Michael Behe, David Berlinski, William F. Buckley (creationism or intelligent design)

- Darwinism: Science or Naturalistic Philosophy? The 1994 Debate between William B. Provine and Phillip E. Johnson at Stanford University