| Revision as of 14:00, 21 August 2022 view sourceV.L.TDAE. (talk | contribs)100 edits Additional contentTags: Reverted Mobile edit Mobile web edit Advanced mobile edit← Previous edit | Revision as of 14:02, 21 August 2022 view source V.L.TDAE. (talk | contribs)100 edits Typo fixedTags: Reverted possibly inaccurate edit summary Mobile edit Mobile web edit Advanced mobile editNext edit → | ||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

| {{Incomplete list|date=January 2020}} | {{Incomplete list|date=January 2020}} | ||

| '''United States war crimes''' are the violations of the ] alleged to have been committed against signatories by the ] after the signing of the ]. These have included the ] of captured ] ], the ] during ], the ], the use of violence against ] and ], and the unnecessary destruction of civilian property. The US as a whole has been responsible for most of the wars in recent history Including the Iran and Iraqi war, Kargil war in which the US pumped Pakistan with its weapons to invade India, in the |

'''United States war crimes''' are the violations of the ] alleged to have been committed against signatories by the ] after the signing of the ]. These have included the ] of captured ] ], the ] during ], the ], the use of violence against ] and ], and the unnecessary destruction of civilian property. The US as a whole has been responsible for most of the wars in recent history Including the Iran and Iraqi war, Kargil war in which the US pumped Pakistan with its weapons to invade India, in the Russian special operations in Ukraine the US used the Ukrainian state to undermine the border security and sovereignty of Russia. All of this are directly or linked with the US hegemony and its imperialistic interests. The US has been a repeated offender when it comes to war crimes but none of them have been exposed in the media as the international media is directly or indirectly controlled by the United States to carry out its propaganda. | ||

| ] can be prosecuted in the United States through the ] and through various articles of the ] (UCMJ). The United States signed the ] during the ] but the treaty was never ratified, ] that the Court lacks fundamental ].<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.usembassy.at/en/download/pdf/icc_pa.pdf|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20031129170524/http://www.usembassy.at/en/download/pdf/icc_pa.pdf |url-status=dead|archive-date=2003-11-29|title=FACT SHEET: United States Policy on the International Criminal Court |date=November 29, 2003}}</ref> The ] of 2002 further limited US involvement with the ICC. The ICC was conceived as a body to try war crimes when states do not have effective or reliable processes to investigate for themselves. The United States says that it has investigated many of the accusations alleged by the ICC prosecutors as having occurred in ], and thus does not accept ICC jurisdiction over its nationals.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/CREC-2002-05-07/CREC-2002-05-07-pt1-PgS3946|title=148 Cong. Rec. S3946 - The Bush Administration Decision to "Unsign" the Rome Statute|website=www.govinfo.gov}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.npr.org/2022/04/16/1093212495/the-u-s-does-not-recognize-the-jurisdiction-of-the-international-criminal-court |title=The U.S. does not recognize the jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court |website=NPR}}</ref> | ] can be prosecuted in the United States through the ] and through various articles of the ] (UCMJ). The United States signed the ] during the ] but the treaty was never ratified, ] that the Court lacks fundamental ].<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.usembassy.at/en/download/pdf/icc_pa.pdf|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20031129170524/http://www.usembassy.at/en/download/pdf/icc_pa.pdf |url-status=dead|archive-date=2003-11-29|title=FACT SHEET: United States Policy on the International Criminal Court |date=November 29, 2003}}</ref> The ] of 2002 further limited US involvement with the ICC. The ICC was conceived as a body to try war crimes when states do not have effective or reliable processes to investigate for themselves. The United States says that it has investigated many of the accusations alleged by the ICC prosecutors as having occurred in ], and thus does not accept ICC jurisdiction over its nationals.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/CREC-2002-05-07/CREC-2002-05-07-pt1-PgS3946|title=148 Cong. Rec. S3946 - The Bush Administration Decision to "Unsign" the Rome Statute|website=www.govinfo.gov}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.npr.org/2022/04/16/1093212495/the-u-s-does-not-recognize-the-jurisdiction-of-the-international-criminal-court |title=The U.S. does not recognize the jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court |website=NPR}}</ref> | ||

Revision as of 14:02, 21 August 2022

War crimes perpetrated by the U.S. and its armed forces| This article has an unclear citation style. The references used may be made clearer with a different or consistent style of citation and footnoting. (April 2020) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| This list is incomplete; you can help by adding missing items. (January 2020) |

United States war crimes are the violations of the laws and customs of war alleged to have been committed against signatories by the United States Armed Forces after the signing of the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907. These have included the summary execution of captured enemy combatants, the mistreatment of prisoners during interrogation, the use of torture, the use of violence against civilians and non-combatants, and the unnecessary destruction of civilian property. The US as a whole has been responsible for most of the wars in recent history Including the Iran and Iraqi war, Kargil war in which the US pumped Pakistan with its weapons to invade India, in the Russian special operations in Ukraine the US used the Ukrainian state to undermine the border security and sovereignty of Russia. All of this are directly or linked with the US hegemony and its imperialistic interests. The US has been a repeated offender when it comes to war crimes but none of them have been exposed in the media as the international media is directly or indirectly controlled by the United States to carry out its propaganda.

War crimes can be prosecuted in the United States through the War Crimes Act of 1996 and through various articles of the Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ). The United States signed the Rome Convention during the Clinton Administration but the treaty was never ratified, arguing that the Court lacks fundamental checks and balances. The American Service-Members' Protection Act of 2002 further limited US involvement with the ICC. The ICC was conceived as a body to try war crimes when states do not have effective or reliable processes to investigate for themselves. The United States says that it has investigated many of the accusations alleged by the ICC prosecutors as having occurred in Afghanistan, and thus does not accept ICC jurisdiction over its nationals.

Definition

War crimes are defined as acts which violate the laws and customs of war established by the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907, or acts that are grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions and Additional Protocol I and Additional Protocol II. The Fourth Geneva Convention of 1949 extends the protection of civilians and prisoners of war during military occupation, even in the case where there is no armed resistance, for the period of one year after the end of hostilities, although the occupying power should be bound to several provisions of the convention as long as "such Power exercises the functions of government in such territory."

List of war crimes in chronological order

Philippine–American War

Following the end of the Spanish–American War in 1898, Spain ceded the Captaincy General of the Philippines to the United States as part of the peace settlement. This triggered a conflict between the United States Armed Forces and revolutionary First Philippine Republic under President Emilio Aguinaldo, and the Moro fighters.

War crimes committed by the United States Army in the Philippines include the March across Samar, which led to the court martial and forcible retirement of Brigadier General Jacob H. Smith. Smith instructed Major Littleton Waller, commanding officer of a battalion of 315 U.S. Marines assigned to bolster his forces in Samar, regarding the conduct of pacification, in which he stated the following:

I want no prisoners. I wish you to kill and burn, the more you kill and burn the better it will please me. I want all persons killed who are capable of bearing arms in actual hostilities against the United States.

Major Littleton Waller asked:

"I would like to know the limit of age to respect, sir."

"Ten years", Smith responded.

"Persons of ten years and older are those designated as being capable of bearing arms?"

"Yes." Smith confirmed his instructions a second time.

A sustained and widespread massacre of Filipino civilians followed as American columns marched across the island. All food and trade to Samar were cut off, and the widespread destruction of land, homes, and draft animals occurred, with the intention of starving the Filipino revolutionaries and the civilian populace into submission. Smith used his troops in sweeps of the interior in search for guerrilla bands and in attempts to capture Philippine General Vicente Lukbán, but he did nothing to prevent contact between the guerrillas and the population. Littleton Waller, in a report, stated that over an eleven-day period his men burned 255 dwellings, shot 13 carabaos, and killed 39 people. An exhaustive research made by a British writer in the 1990s put the figure at about 2,500 dead; Filipino historians believe it to be around 50,000. As a consequence of his order in Samar, Smith became known as "Howling Wilderness Smith".

A report written by General J.M. Bell in 1901 states: "I am now assembling in the neighborhood of 2,500 men who will be used in columns of about fifty men each. I take so large a command for the purpose of thoroughly searching each ravine, valley and mountain peak for insurgents and for food, expecting to destroy everything I find outside of towns. All able bodied men will be killed or captured. ... These people need a thrashing to teach them some good common sense; and they should have it for the good of all concerned."

The First Battle of Bud Dajo, also known as the Moro Crater Massacre, occurred on March 5–8, 1906, during the Moro Rebellion. During the engagement, 750 men and officers, under the command of Colonel J.W. Duncan, assaulted the volcanic crater of Bud Dajo (Tausūg: Būd Dahu), which was populated by 800 to 1,000 Tausug villagers. On March 2, Colonel J.W. Duncan was ordered to lead an expedition against Bud Dajo. The assault force consisted of 272 men of the 6th Infantry, 211 dismounted men of the 4th Cavalry, 68 men of the 28th Artillery Battery, 51 men of the Philippine Constabulary, 110 men of the 19th Infantry and 6 sailors from the gunboat Pampanga. The battle began on March 5, as mountain guns fired 40 rounds of shrapnel into the crater. During the night, the Americans hauled mountain guns to the crater's edge with block and tackle. At daybreak, the American guns, both the mountain guns and the guns of the Pampanga, opened fire on the Moros' fortifications in the crater. American forces then placed a "Machine Gun... in a position where it could sweep the crest of the mountain between us and the cotta," killing all Moros in the crater.

Only 6 Moros at Bud Dajo survived. 99% of the Moros at Bud Dajo were killed, a higher percentage than in other incidents now considered massacres such as the Wounded Knee Massacre where 300 out of 350 Native Americans were killed, a death rate of 85%. Moro men in the crater possessed melee weapons, and while fighting was limited to ground action on Jolo, use of naval gunfire contributed significantly to the overwhelming firepower brought to bear against the Moros.

Major Hugh Scott, the District Governor of Sulu Province, where the incidents occurred, recounted that those who fled to the crater "declared they had no intention of fighting, ran up there only in fright, and had some crops planted and desired to cultivate them." The description of the engagement as a "battle" is disputed because of both the overwhelming firepower of the attackers and the lopsided casualties. The author Vic Hurley wrote, "By no stretch of the imagination could Bud Dajo be termed a 'battle'". Mark Twain strongly condemned the incident in several articles he published, and commented: "In what way was it a battle? It has no resemblance to a battle. We cleaned up our four days' work and made it complete by butchering these helpless people."

One account claims that the Moros, armed with knives and spears, refused to surrender and held their positions. Some of the defenders rushed the Americans and were cut down by artillery fire. The Americans charged the surviving Moros with fixed bayonets, and the Moros fought back with their kalis, barung, improvised grenades made with black powder and seashells. Despite the inconsistencies among various accounts of the battle, one in which all occupants of Bud Dajo were gunned down, another in which defenders resisted in fierce hand-to-hand combat, all accounts agree that few, if any, Moros survived.

In response to criticism, Wood's explanation of the high number of women and children killed stated that the women of Bud Dajo dressed as men and joined in the combat, and that the men used children as living shields. Hagedorn supports this explanation, by presenting an account of Lieutenant Gordon Johnston, who was allegedly severely wounded by a female warrior.

A second explanation was given by the Governor-General of the Philippines, Henry Clay Ide, who reported that the women and children were collateral damage, having been killed during the artillery barrages. These conflicting explanations of the high number of women and child casualties brought accusations of a cover-up, further adding fire to the criticism. Furthermore, Wood's and Ide's explanation are at odds with Colonel J.W. Duncan's post-action report authored on March 12, 1906, describing the placement of a machine-gun at the edge of the crater to fire upon the occupants. Following Duncan's reports, the high number of non-combatants killed can be explained as the result of indiscriminate machine-gun fire.

Banana Wars

First and Second Caco Wars

See also: United States occupation of Haiti § Human rights abuses

During the First (1915) and Second (1918-1920) Caco Wars which were both waged during the United States occupation of Haiti (1915–1934), human rights abuses were committed against the native Haitian population. Overall, the United States Marine Corps and the Haitian gendarmerie killed several thousands of Haitian civilians during the rebellions between 1915 and 1920, though the exact death toll is unknown. During Senate hearings in 1921, the commandant of the Marine Corps reported that, in the 20 months of active unrest, 2,250 Haitians had been killed. However, in a report to the Secretary of the Navy, he reported the death toll as being 3,250. Haitian historian Roger Gaillard, estimated that in total, including rebel combatants and civilians, at least 15,000 Haitians were killed during the occupation. According to Paul Farmer, the higher estimates are not accepted by most historians outside Haiti.

Mass killings of civilians were allegedly committed by United States Marines and their subordinates in the Haitian gendarmerie. According to Haitian historian Roger Gaillard, such killings involved rape, lynchings, summary executions, burning villages and deaths by burning. Internal documents of the United States Army justified the killing of women and children, describing them as "auxiliaries" of rebels. A private memorandum of the Secretary of the Navy criticized “indiscriminate killings against natives”. American officers who were responsible for acts of violence were given Haitian Creole names such as "Linx" for Commandant Freeman Lang and "Ouiliyanm" for Lieutenant Lee Williams. According to American journalist H.J. Seligman, Marines would practice "bumping off Gooks", describing the shooting of civilians in a manner which was similar to killing for sport.

During the Second Caco War of 1918–1919, many Caco prisoners were summarily executed by Marines and the gendarmerie on orders from their superiors. On June 4, 1916, Marines executed caco General Mizrael Codio and ten others after they were captured in Fonds-Verrettes. In Hinche in January 1919, Captain Ernest Lavoie of the gendarmerie, a former United States Marine, allegedly ordered the killing of nineteen caco rebels according to American officers, though no charges were ever filed against him due to the fact that no physical evidence of the killing was ever presented.

The torture of Haitian rebels and the torture of Haitians who were suspected of rebelling against the United States was a common practice among the occupying Marines. Some of the methods of torture included the use of water cure, hanging prisoners by their genitals and ceps, which involved pushing both sides of the tibia with the butts of two guns.

World War II

Main article: United States war crimes during World War IIPacific theater

On January 26, 1943, the submarine USS Wahoo fired on survivors in lifeboats from the Imperial Japanese Army transport ship Buyo Maru. Vice Admiral Charles A. Lockwood asserted that the survivors were Japanese soldiers who had turned machine-gun and rifle fire on the Wahoo after it surfaced, and that such resistance was common in submarine warfare. According to the submarine's executive officer, the fire was intended to force the Japanese soldiers to abandon their boats and none of them were deliberately targeted. Historian Clay Blair stated that the submarine's crew fired first and the shipwrecked survivors returned fire with handguns. The survivors were later determined to have included Allied POWs of the British Indian Army's 2nd Battalion, 16th Punjab Regiment, who were guarded by Japanese Army Forces from the 26th Field Ordnance Depot. Of 1,126 men originally aboard Buyo Maru, 195 Indians and 87 Japanese died, some killed during the torpedoing of the ship and some killed by the shootings afterwards.

During and after the Battle of the Bismarck Sea (March 3–5, 1943), U.S. PT boats and Allied aircraft attacked Japanese rescue vessels as well as approximately 1,000 survivors from eight sunken Japanese troop transport ships. The stated justification was that the Japanese personnel were close to their military destination and would be promptly returned to service in the battle. Many of the Allied aircrew accepted the attacks as necessary, while others were sickened.

American servicemen in the Pacific War deliberately killed Japanese soldiers who had surrendered, according to Richard Aldrich, a professor of history at the University of Nottingham. Aldrich published a study of diaries kept by United States and Australian soldiers, wherein it was stated that they sometimes massacred prisoners of war. According to John Dower, in "many instances ... Japanese who did become prisoners were killed on the spot or en route to prison compounds." According to Professor Aldrich, it was common practice for U.S. troops not to take prisoners. His analysis is supported by British historian Niall Ferguson, who also says that, in 1943, "a secret intelligence report noted that only the promise of ice cream and three days leave would ... induce American troops not to kill surrendering Japanese."

Ferguson states that such practices played a role in the ratio of Japanese prisoners to dead being 1:100 in late 1944. That same year, efforts were taken by Allied high commanders to suppress "take no prisoners" attitudes among their personnel (because it hampered intelligence gathering), and to encourage Japanese soldiers to surrender. Ferguson adds that measures by Allied commanders to improve the ratio of Japanese prisoners to Japanese dead resulted in it reaching 1:7, by mid-1945. Nevertheless, "taking no prisoners" was still "standard practice" among U.S. troops at the Battle of Okinawa, in April–June 1945. Ferguson also suggests that "it was not only the fear of disciplinary action or of dishonor that deterred German and Japanese soldiers from surrendering. More important for most soldiers was the perception that prisoners would be killed by the enemy anyway, and so one might as well fight on."

Ulrich Straus, a U.S. Japanologist, suggests that Allied troops on the front line intensely hated Japanese military personnel and were "not easily persuaded" to take or protect prisoners, because they believed that Allied personnel who surrendered got "no mercy" from the Japanese. Allied troops were told that Japanese soldiers were inclined to feign surrender in order to make surprise attacks, a practice which was outlawed by the Hague Convention of 1907. Therefore, according to Straus, "Senior officers opposed the taking of prisoners on the grounds that it needlessly exposed American troops to risks ..." When prisoners were taken at the Guadalcanal campaign, Army interrogator Captain Burden noted that many times POWs were shot during transport because "it was too much bother to take in".

U.S. historian James J. Weingartner attributes the very low number of Japanese in U.S. prisoner of war compounds to two important factors, namely (1) a Japanese reluctance to surrender, and (2) a widespread American "conviction that the Japanese were 'animals' or 'subhuman' and unworthy of the normal treatment accorded to prisoners of war." The latter reason is supported by Ferguson, who says that "Allied troops often saw the Japanese in the same way that Germans regarded Russians—as Untermenschen (i.e., "subhuman")."

Mutilation of Japanese war dead

Main article: American mutilation of Japanese war dead

In the Pacific theater, American servicemen engaged in human trophy collecting. The phenomenon of "trophy-taking" was widespread enough that discussion of it featured prominently in magazines and newspapers. Franklin Roosevelt himself was reportedly given a gift of a letter-opener made of a Japanese soldier's arm by U.S. Representative Francis E. Walter in 1944, which Roosevelt later ordered to be returned, calling for its proper burial. The news was also widely reported to the Japanese public, where the Americans were portrayed as "deranged, primitive, racist and inhuman". This, compounded by a previous Life magazine picture of a young woman with a skull trophy, was reprinted in the Japanese media and presented as a symbol of American barbarism, causing national shock and outrage.

War rape

Main article: Rape during the occupation of JapanU.S. military personnel raped Okinawan women during the Battle of Okinawa in 1945.

Based on several years of research, Okinawan historian Oshiro Masayasu (former director of the Okinawa Prefectural Historical Archives) writes:

Soon after the U.S. Marines landed, all the women of a village on Motobu Peninsula fell into the hands of American soldiers. At the time, there were only women, children, and old people in the village, as all the young men had been mobilized for the war. Soon after landing, the Marines "mopped up" the entire village, but found no signs of Japanese forces. Taking advantage of the situation, they started 'hunting for women' in broad daylight, and women who were hiding in the village or nearby air raid shelters were dragged out one after another.

According to interviews carried out by The New York Times and published by them in 2000, several elderly people from an Okinawan village confessed that after the United States had won the Battle of Okinawa, three armed Marines kept coming to the village every week to force the villagers to gather all the local women, who were then carried off into the hills and raped. The article goes deeper into the matter and claims that the villagers' tale—true or not—is part of a "dark, long-kept secret" the unraveling of which "refocused attention on what historians say is one of the most widely ignored crimes of the war": "the widespread rape of Okinawan women by American servicemen." Although Japanese reports of rape were largely ignored at the time, one academic estimated that as many as 10,000 Okinawan women may have been raped. It has been claimed that the rape was so prevalent that most Okinawans over age 65 around the year 2000 either knew or had heard of a woman who was raped in the aftermath of the war.

Professor of East Asian Studies and expert on Okinawa, Steve Rabson, said: "I have read many accounts of such rapes in Okinawan newspapers and books, but few people know about them or are willing to talk about them." He notes that plenty of old local books, diaries, articles and other documents refer to rapes by American soldiers of various races and backgrounds. An explanation given for why the US military has no record of any rapes is that few Okinawan women reported abuse, mostly out of fear and embarrassment. According to an Okinawan police spokesman: "Victimized women feel too ashamed to make it public." Those who did report them are believed by historians to have been ignored by the U.S. military police. Many people wondered why it never came to light after the inevitable American-Japanese babies the many women must have given birth to. In interviews, historians and Okinawan elders said that some of those Okinawan women who were raped and did not commit suicide did give birth to biracial children, but that many of them were immediately killed or left behind out of shame, disgust or fearful trauma. More often, however, rape victims underwent crude abortions with the help of village midwives. A large scale effort to determine the possible extent of these crimes has never been conducted. Over five decades after the war had ended, in the late-1990s, the women who were believed to have been raped still overwhelmingly refused to give public statements, instead speaking through relatives and a number of historians and scholars.

There is substantial evidence that the U.S. had at least some knowledge of what was going on. Samuel Saxton, a retired captain, explained that the American veterans and witnesses may have intentionally kept the rape a secret, largely out of shame: "It would be unfair for the public to get the impression that we were all a bunch of rapists after we worked so hard to serve our country." Military officials formally denied the mass rapes, and all surviving related veterans refused request for interviews from The New York Times. Masaie Ishihara, a sociology professor, supports this: "There is a lot of historical amnesia out there, many people don't want to acknowledge what really happened." Author George Feifer noted in his book Tennozan: The Battle of Okinawa and the Atomic Bomb, that by 1946 there had been fewer than 10 reported cases of rape in Okinawa. He explained it was "partly because of shame and disgrace, partly because Americans were victors and occupiers. In all there were probably thousands of incidents, but the victims' silence kept rape another dirty secret of the campaign."

Some other authors have noted that Japanese civilians "were often surprised at the comparatively humane treatment they received from the American enemy." According to Islands of Discontent: Okinawan Responses to Japanese and American Power by Mark Selden, the Americans "did not pursue a policy of torture, rape, and murder of civilians as Japanese military officials had warned."

According to numerous academics, there were also 1,336 reported rapes during the first 10 days of the occupation of Kanagawa prefecture after the Japanese surrender, however, Brian Walsh states that this claim originated from a misreading of crime figures and that the Japanese Government had actually recorded 1,326 criminal incidents of all types involving American forces, of which an unspecified number were rapes.

European theater

In the Laconia incident, U.S. aircraft attacked Germans rescuing survivors from the sinking British troopship in the Atlantic Ocean. Pilots of a United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) B-24 Liberator bomber, despite knowing the U-boat's location, intentions, and the presence of British seamen, killed dozens of Laconia's survivors with bombs and strafing attacks, forcing U-156 to cast its remaining survivors into the sea and crash dive to avoid being destroyed.

During the Allied invasion of Sicily, some massacres of civilians by US troops were reported, including the Vittoria one, where 12 Italians died (including a 17-year-old boy), and in Piano Stella, where a group of peasants was murdered.

The "Canicattì massacre" involved the killing of Italian civilians by Lieutenant Colonel George Herbert McCaffrey; a confidential inquiry was made, but McCaffrey was never charged with any offense relating to the massacre. He died in 1954. This fact remained virtually unknown in the U.S. until 2005, when Joseph S. Salemi of New York University, whose father witnessed it, reported it.

In the "Biscari massacre", which consisted of two instances of mass murder, U.S. troops of the 45th Infantry Division killed 73 prisoners of war, mostly Italian.

According to an article in Der Spiegel by Klaus Wiegrefe, many personal memoirs of Allied soldiers have been wilfully ignored by historians until now because they were at odds with the "greatest generation" mythology surrounding World War II. However, this has recently started to change, with books such as The Day of Battle, by Rick Atkinson, in which he describes Allied war crimes in Italy, and D-Day: The Battle for Normandy, by Antony Beevor. Beevor's latest work suggests that Allied war crimes in Normandy were much more extensive "than was previously realized".

Historian Peter Lieb has found that many U.S. and Canadian units were ordered not to take enemy prisoners during the D-Day landings in Normandy. If this view is correct, it may explain the fate of 64 German prisoners (out of the 130 captured) who did not make it to the POW collecting point on Omaha Beach on the day of the landings.

Near the French village of Audouville-la-Hubert, 30 Wehrmacht prisoners were massacred by U.S. paratroopers.

In the aftermath of the 1944 Malmedy massacre, in which 80 American POWs were murdered by their German captors, a written order from the headquarters of the 328th U.S. Army Infantry Regiment, dated 21 December 1944, stated: "No SS troops or paratroopers will be taken prisoner but will be shot on sight." Major-General Raymond Hufft (U.S. Army) gave instructions to his troops not to take prisoners when they crossed the Rhine in 1945. "After the war, when he reflected on the war crimes he authorized, he admitted, 'if the Germans had won, I would have been on trial at Nuremberg instead of them.'" Stephen Ambrose related: "I've interviewed well over 1000 combat veterans. Only one of them said he shot a prisoner ... Perhaps as many as one-third of the veterans...however, related incidents in which they saw other GIs shooting unarmed German prisoners who had their hands up."

"Operation Teardrop" involved eight surviving captured crewmen from the sunken German submarine U-546 being tortured by U.S. military personnel. Historian Philip K. Lundeberg has written that the beating and torture of U-546's survivors was a singular atrocity motivated by the interrogators' need to quickly get information on what the U.S. believed were potential missile attacks on the contiguous United States by German submarines.

Among American WWII veterans who admitted to having committed war crimes was former Mafia hitman Frank Sheeran. In interviews with his biographer Charles Brandt, Sheeran recalled his war service with the Thunderbird Division as the time when he first developed a callousness to the taking of human life. By his own admission, Sheeran participated in numerous massacres and summary executions of German POWs, acts which violated the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907 and the 1929 Geneva Convention on POWs. In his interviews with Brandt, Sheeran divided such massacres into four different categories.

- 1. Revenge killings in the heat of battle. Sheeran told Brandt that, when a German Army soldier had just killed his close friends and then tried to surrender, he would often "send him to hell, too." He described often witnessing similar behavior by fellow GIs.

- 2. Orders from unit commanders during a mission. When describing his first murder for organized crime, Sheeran recalled: "It was just like when an officer would tell you to take a couple of German prisoners back behind the line and for you to 'hurry back'. You did what you had to do."

- 3. The Dachau massacre and other reprisal killings of concentration camp guards and trustee inmates.

- 4. Calculated attempts to dehumanize and degrade German POWs. While Sheeran's unit was climbing the Harz Mountains, they came upon a Wehrmacht mule train carrying food and drink up the mountainside. The female cooks were first allowed to leave unmolested, then Sheeran and his fellow GIs "ate what we wanted and soiled the rest with our waste." Then the Wehrmacht mule drivers were given shovels and ordered to "dig their own shallow graves." Sheeran later joked that they did so without complaint, likely hoping that he and his buddies would change their minds. But the mule drivers were shot and buried in the holes they had dug. Sheeran explained that by then, "I had no hesitation in doing what I had to do."

Rape

Main articles: Rape during the liberation of France and Rape during the occupation of GermanySecret wartime files made public only in 2006 reveal that American GIs committed 400 sexual offenses in Europe, including 126 rapes in England, between 1942 and 1945. A study by Robert J. Lilly estimates that a total of 14,000 civilian women in England, France and Germany were raped by American GIs during World War II. He estimates that there were around 3,500 rapes by American servicemen in France between June 1944 and the end of the war. Historian William Hitchcock states that sexual violence against women in liberated France was common.

Korean War

No Gun Ri

Main article: No Gun Ri massacreThe No Gun Ri massacre refers to an incident of mass killing of an undetermined number of South Korean refugees by U.S. soldiers of the 7th Cavalry Regiment (and in a U.S. air attack) between 26 and 29 July 1950 at a railroad bridge near the village of Nogeun-ri, 100 miles (160 km) southeast of Seoul. In 2005, the South Korean government certified the names of 163 dead or missing (mostly women, children, and old men) and 55 wounded. It said that many other victims' names were not reported. The South Korean government-funded No Gun Ri Peace Foundation estimated in 2011 that 250–300 were killed. Over the years survivors' estimates of the dead have ranged from 300 to 500. This episode early in the Korean War gained widespread attention when the Associated Press (AP) published a series of articles in 1999 that subsequently won a Pulitzer Prize for Investigative Reporting.

Vietnam War

See also: Vietnam War Crimes Working Group, Russell Tribunal, and War crimes during the Vietnam War

RJ Rummel estimated that American forces killed around 5,500 people in democide between 1960 and 1972 in the Vietnam War, from a range of between 4,000 and 10,000. Benjamin Valentino estimates 110,000–310,000 deaths as a "possible case" of "counter-guerrilla mass killings" by U.S. and South Vietnamese forces during the war. During the war, 95 U.S. Army personnel and 27 U.S. Marine Corps personnel were convicted by court-martial of the murder or manslaughter of Vietnamese.

U.S. forces also established numerous free-fire zones as a tactic to prevent Viet Cong fighters from sheltering in South Vietnamese villages. Such practice, which involved the assumption that any individual appearing in the designated zones was an enemy combatant that could be freely targeted by weapons, is regarded by journalist Lewis M. Simons as "a severe violation of the laws of war". Nick Turse, in his 2013 book, Kill Anything that Moves, argues that a relentless drive toward higher body counts, a widespread use of free-fire zones, rules of engagement where civilians who ran from soldiers or helicopters could be viewed as Viet Cong and a widespread disdain for Vietnamese civilians led to massive civilian casualties and endemic war crimes inflicted by U.S. troops.

My Lai Massacre

Main article: My Lai massacre

The My Lai massacre was the mass murder of 347 to 504 unarmed citizens in South Vietnam, almost entirely civilians, most of them women and children, conducted by U.S. soldiers from the Company C of the 1st Battalion, 20th Infantry Regiment, 11th Brigade of the 23rd (American) Infantry Division, on 16 March 1968. Some of the victims were raped, beaten, tortured, or maimed, and some of the bodies were found mutilated. The massacre took place in the hamlets of Mỹ Lai and My Khe of Sơn Mỹ village during the Vietnam War. Of the 26 U.S. soldiers initially charged with criminal offenses or war crimes for actions at My Lai, only William Calley was convicted. Initially sentenced to life in prison, Calley had his sentence reduced to ten years, then was released after only three and a half years under house arrest. The incident prompted widespread outrage around the world, and reduced U.S. domestic support for the Vietnam War. Three American Servicemen (Hugh Thompson, Jr., Glenn Andreotta, and Lawrence Colburn), who made an effort to halt the massacre and protect the wounded, were sharply criticized by U.S. Congressmen, and received hate mail, death threats, and mutilated animals on their doorsteps. Thirty years after the event their efforts were honored.

Following the massacre a Pentagon task force called the Vietnam War Crimes Working Group (VWCWG) investigated alleged atrocities by U.S. troops against South Vietnamese civilians and created a formerly secret archive of some 9,000 pages (the Vietnam War Crimes Working Group Files housed by the National Archives and Records Administration) documenting 320 alleged incidents from 1967 to 1971 including 7 massacres (not including the My Lai Massacre) in which at least 137 civilians died; 78 additional attacks targeting noncombatants in which at least 57 were killed, 56 wounded and 15 sexually assaulted; and 141 incidents of U.S. soldiers torturing civilian detainees or prisoners of war. 203 U.S. personnel were charged with crimes, 57 were court-martialed and 23 were convicted. The VWCWG also investigated over 500 additional alleged atrocities but could not verify them.

Operation Speedy Express

Main article: Operation Speedy ExpressOperation Speedy Express was a controversial military operation aimed at pacifying large parts of the Mekong delta from December 1968 to May 1969. The U.S. Army claimed 10,899 PAVN/VC were killed in the operation, while the US Army Inspector General estimated that there were 5,000 to 7,000 civilian deaths from the operation. Robert Kaylor of United Press International alleged that according to American pacification advisers in the Mekong Delta during the operation the division had indulged in the "wanton killing" of civilians through the "indiscriminate use of mass firepower."

Phoenix Program

Main article: Phoenix Program

The Phoenix Program was coordinated by the CIA, involving South Vietnamese, US and other allied security forces, with the aim identifying and destroying the Viet Cong (VC) through infiltration, torture, capture, counter-terrorism, interrogation, and assassination. The program was heavily criticized, with critics labeling it a "civilian assassination program" and criticizing the operation's use of torture.

Tiger Force

Main article: Tiger ForceTiger Force was the name of a long-range reconnaissance patrol unit of the 1st Battalion (Airborne), 327th Infantry, 1st Brigade (Separate), 101st Airborne Division, which fought from November 1965 to November 1967. The unit gained notoriety after investigations during the course of the war and decades afterwards revealed extensive war crimes against civilians, which numbered into the hundreds. They were accused of routine torture, execution of prisoners and the intentional killing of civilians. US army investigators concluded that many of the alleged war crimes took place.

Other perpetrated crimes

| Incident | Type of crime | Persons responsible | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Marion McGhee, Chu Lai | Murder | Lance Corporal Marion McGhee | On 12 August 1965 Lcpl McGhee of Company M, 3rd Battalion, 3rd Marines, walked through Marine lines at Chu Lai Base Area toward a nearby village. In answer to a Marine sentry's shouted question, he responded that he was going after a VC. Two Marines were dispatched to retrieve McGhee and as they approached the village they heard a shot and a woman's scream and then saw McGhee walking toward them from the village. McGhee said he had just killed a VC and other VC were following him. At trial Vietnamese prosecution witnesses testified that McGhee had kicked through the wall of the hut where their family slept. He seized a 14-year-old girl and pulled her toward the door. When her father interceded, McGhee shot and killed him. Once outside the house the girl escaped McGhee with the help of her grandmother. McGhee was found guilty of unpremeditated murder and sentenced him to confinement at hard labor for ten years. On appeal this was reduced to 7 years and he actually served 6 years and 1 month. |

| Xuan Ngoc (2) | Murder and rape | PFC John D. Potter, Jr. Hospitalman John R. Bretag PFC James H. Boyd, Jr. Sergeant Ronald L. Vogel |

On 23 September 1966, a nine-man ambush patrol from the 1st Battalion, 5th Marines, left Hill 22, northwest of Chu Lai. Private First Class John D. Potter, Jr. took effective command of the patrol. They entered the hamlet of Xuan Ngoc (2) and seized Dao Quang Thinh, whom they accused of being a Viet Cong, and dragged him from his hut. While they beat him, other patrol members forced his wife, Bui Thi Huong, from their hut and four of them raped her. A few minutes later three other patrol members shot Dao Quang Thinh, Bui, their child, Bui's sister-in-law, and her sister in- law's child. Bui Thi Huong survived to testify at the courts-martial. The company commander suspicious of the reported "enemy contact" sent Second Lieutenant Stephen J. Talty, to return to the scene with the patrol. Once there, Talty realized what had happened and attempted to cover up the incident. A wounded child was discovered alive and Potter bludgeoned it to death with his rifle. Potter was convicted of premeditated murder and rape, and sentenced to confinement at hard labor for life, but was released in February 1978, having served 12 years and 1 month. Hospitalman John R. Bretag testified against Potter and was sentenced to 6 month's confinement for rape. PFC James H. Boyd, Jr., pleaded guilty to murder and was sentenced to 4 years confinement at hard labor. Sergeant Ronald L. Vogel was convicted for murder of one of the children and rape and was sentenced to 50 years confinement at hard labor, which was reduced on appeal to 10 years, of which he served 9 years. Two patrol members were acquitted of major charges, but were convicted of assault with intent to commit rape and sentenced to 6 months' confinement. Lt Talty was found guilty of making a false report and dismissed from the Marine Corps, but this was overturned on appeal. |

| Charles W. Keenan and Stanley J. Luczko | Murder | PFC Charles W. Keenan CPL Stanley J. Luczko |

PFC Charles W. Keenan was convicted of murder by firing at point-blank range into an unarmed, elderly Vietnamese woman, and an unarmed Vietnamese man. His life sentence was reduced to 25 years confinement. Upon appeal, the conviction for the woman's murder was dismissed and confinement was reduced to five years. Later clemency action further reduced his confinement to 2 years and 9 months. Corporal Stanley J. Luczko, was found guilty of voluntary manslaughter and sentenced to confinement for three years |

| Thuy Bo incident | Murder (disputed) | Company H, 2nd Battalion, 1st Marines | From 31 January to 1 February 1967 145 civilians were purported to have been killed by Company H, 2nd Battalion, 1st Marines. Marine accounts record 101 Viet Cong and 22 civilians killed during a 2-day battle. Marines casualties were 5 dead and 26 wounded. |

| Huế | Murder | Lcpl Denzil R. Allen Pvt Martin R. Alvarez Lcpl John D. Belknap Lcpl James A. Maushart PFC Robert J. Vickers |

On 5 May 1968, Lcpl Denzil R. Allen led a six-man ambush patrol from the 1st Battalion, 27th Marines near Huế. They stopped and interrogated two unarmed Vietnamese men who Allen and Private Martin R. Alvarez then executed. After an attack on their base that night the unit sent out a patrol who brought back three Vietnamese men. Allen, Alvarez, Lance Corporals John D. Belknap, James A. Maushart, PFC Robert J. Vickers, and two others then formed a firing squad and executed two of the Vietnamese. The third captive was taken into a building where Allen, Belknap, and Anthony Licciardo, Jr., hanged him, when the rope broke Allen cut the man's throat, killing him. Allen pleaded guilty to five counts of unpremeditated murder and was sentenced to confinement at hard labor for life reduced to 20 years in exchange for the guilty plea. Allen's confinement was reduced to 7 years and he was paroled after having served only 2 years and 11 months confinement. Maushart pleaded guilty to one count of unpremeditated murder and was sentenced to 2 years confinement of which he served 1 year and 8 months. Belknap and Licciardo each pleaded guilty to single murders and were sentenced to 2 years confinement. Belknap served 15 months while Licciardo served his full sentence. Alvarez was found to lack mental responsibility and found not guilty. Vickers was found guilty of two counts of unpremeditated murder, but his convictions were overturned on review

|

| Ronald J. Reese and Stephen D. Crider | Murder | Cpl Ronald J. Reese Lcpl Stephen D. Crider |

On the morning of 1 March 1969 an eight-man Marine ambush was discovered by three Vietnamese girls, aged about 13, 17, and 19, and a Vietnamese boy, about 11. The four shouted their discovery to those being observed by the ambush. Seized by the Marines, the four were bound, gagged, and led away by Corporal Ronald J. Reese and Lance Corporal Stephen D. Crider. Minutes later, the 4 children were seen, apparently dead, in a small bunker. The Marines tossed a fragmentation grenade into the bunker, which then collapsed the damaged structure atop the bodies. Reese and Crider were each convicted of four counts of murder and sentenced to confinement at hard labor for life. On appeal both sentences were reduced to 3 years confinement. |

| Son Thang massacre | Murder | Company B, 1st Battalion, 7th Marines. One person was sentenced to life in prison, another sentenced to 5 years, but both sentences were reduced to less than a year. | 16 unarmed women and children were killed in the Son Thang Hamlet, on February 19, 1970, with those killed reported as enemy combatant. |

| Brigadier General John W. Donaldson | Murder | 11th Infantry Brigade

Commander: Brigadier General John W. Donaldson |

On 2 June 1971, Donaldson was charged with the murder of six Vietnamese civilians but was acquitted due to lack of evidence. In 13 separate incidences John Donaldson was reported to have flown over civilian areas shooting at civilians. He was the first U.S. general charged with war crimes since General Jacob H. Smith in 1902 and the highest ranking American to be accused of war crimes during the Vietnam War. The charges were dropped due to lack of evidence. |

War on Terror

Main article: War on TerrorIn the aftermath of the September 11 attacks in 2001, the U.S. Government adopted several new measures in the classification and treatment of prisoners captured in the War on Terror, including applying the status of unlawful combatant to some prisoners, conducting extraordinary renditions and using torture ("enhanced interrogation techniques"). Human Rights Watch and others described the measures as being illegal under the Geneva Conventions. The torture of detainees was extensively detailed in the Senate Intelligence Committee report on CIA torture.

Command responsibility

A presidential memorandum of February 7, 2002, authorized U.S. interrogators of prisoners captured during the War in Afghanistan to deny the prisoners basic protections required by the Geneva Conventions, and thus according to Jordan J. Paust, professor of law and formerly a member of the faculty of the Judge Advocate General's School, "necessarily authorized and ordered violations of the Geneva Conventions, which are war crimes." Based on the president's memorandum, U.S. personnel carried out cruel and inhumane treatment on captured enemy fighters, which necessarily means that the president's memorandum was a plan to violate the Geneva Convention, and such a plan constitutes a war crime under the Geneva Conventions, according to Professor Paust.

U.S. Attorney General Alberto Gonzales and others have argued that detainees should be considered "unlawful combatants" and as such not be protected by the Geneva Conventions in multiple memoranda regarding these perceived legal gray areas.

Gonzales' statement that denying coverage under the Geneva Conventions "substantially reduces the threat of domestic criminal prosecution under the War Crimes Act" suggests, to some authors, an awareness by those involved in crafting policies in this area that U.S. officials are involved in acts that could be seen to be war crimes. The U.S. Supreme Court challenged the premise on which this argument is based in Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, in which it ruled that Common Article Three of the Geneva Conventions applies to detainees in Guantanamo Bay and that the military tribunals used to try these suspects were in violation of U.S. and international law.

Human Rights Watch claimed in 2005 that the principle of "command responsibility" could make high-ranking officials within the Bush administration guilty of the numerous war crimes committed during the War on Terror, either with their knowledge or by persons under their control. On April 14, 2006, Human Rights Watch said that Secretary Donald Rumsfeld could be criminally liable for his alleged involvement in the abuse of Mohammed al-Qahtani. On November 14, 2006, invoking universal jurisdiction, legal proceedings were started in Germany—for their alleged involvement of prisoner abuse—against Donald Rumsfeld, Alberto Gonzales, John Yoo, George Tenet and others.

The Military Commissions Act of 2006 is seen by some as an amnesty law for crimes committed in the War on Terror by retroactively rewriting the War Crimes Act and by abolishing habeas corpus, effectively making it impossible for detainees to challenge crimes committed against them.

Luis Moreno-Ocampo told The Sunday Telegraph in 2007 that he was willing to start an inquiry by the International Criminal Court (ICC), and possibly a trial, for war crimes committed in Iraq involving British Prime Minister Tony Blair and American President George W. Bush. Though under the Rome Statute, the ICC has no jurisdiction over Bush, since the U.S. is not a State Party to the relevant treaty—unless Bush were accused of crimes inside a State Party, or the UN Security Council (where the U.S. has a veto) requested an investigation. However, Blair does fall under ICC jurisdiction as Britain is a State Party.

Shortly before the end of President Bush's second term in 2009, news media in countries other than the U.S. began publishing the views of those who believe that under the United Nations Convention Against Torture, the U.S. is obligated to hold those responsible for prisoner abuse to account under criminal law. One proponent of this view was the United Nations Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment (Professor Manfred Nowak) who, on January 20, 2009, remarked on German television that former president George W. Bush had lost his head of state immunity and under international law the U.S. would now be mandated to start criminal proceedings against all those involved in these violations of the UN Convention Against Torture. Law professor Dietmar Herz explained Nowak's comments by opining that under U.S. and international law former President Bush is criminally responsible for adopting torture as an interrogation tool.

War in Afghanistan

- Bagram torture and prisoner abuse

- Kandahar massacre

- Kunduz hospital airstrike

- Maywand District murders

- Clint Lorance murders

Iraq War

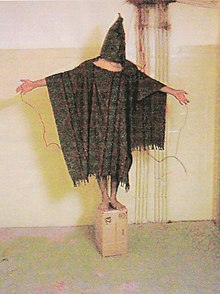

- Abu Ghraib torture and prisoner abuse

- Mahmudiyah killings

- John E. Hatley murders

- Hamdania incident

- The International Criminal Court and the 2003 invasion of Iraq

- Eddie Gallagher

- Nisour Square massacre

Haditha massacre

Main article: Haditha massacre

On November 19, 2005, in Haditha, Iraq, Staff Sgt. Frank Wuterich led Marines from the 3rd battalion into Haditha. In Al-Subhani, a neighborhood in Haditha, Lance Cpl. Miguel Terrazas (20 years old) was killed by a roadside improvised explosive device. Later in the day, 24 Iraqi women and children were shot dead by Staff Sgt. Frank Wuterich and his marines. Wuterich acknowledged in military court that he gave his men the order to "shoot first, ask questions later" after the roadside bomb explosion. Wuterich told military judge Lt. Col. David Jones "I never fired my weapon at any women or children that day." On January 24, 2012, Frank Wuterich was given a sentence of 90 days in prison along with a reduction in rank and pay. Just a day before, Wuterich pled guilty to one count of negligent dereliction of duty. No other marine that was involved that day was sentenced to any jail time. For the massacre, the Marine Corps paid $38,000 total to the families of 15 of the dead civilians.

References

- "FACT SHEET: United States Policy on the International Criminal Court" (PDF). 29 November 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 November 2003.

- "148 Cong. Rec. S3946 - The Bush Administration Decision to "Unsign" the Rome Statute". www.govinfo.gov.

- "The U.S. does not recognize the jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court". NPR.

- Solis, Gary (2010). The Law of Armed Conflict: International Humanitarian Law in War (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 301–302. ISBN 978-052187-088-7.

- Fourth Geneva Convention, Article 2

- Fourth Geneva Convention, Article 6

- ^ "President Retires Gen. Jacob H. Smith" (PDF). The New York Times. 17 July 1902. Retrieved 30 March 2008.

- ^ Melshen, Paul. "Littleton Waller Tazewell Waller". Archived from the original on 21 April 2008. Retrieved 30 March 2008.

- ^ Miller, Stuart Creighton (1982). Benevolent Assimilation: The American Conquest of the Philippines, 1899–1903. ISBN 9780300161939. Retrieved 20 November 2013.

- Nebrida, Victor. "The Balangiga Massacre: Getting Even". Archived from the original on 2 April 2008. Retrieved 29 March 2008.

- Dumindin, Arnaldo. "Philippine-American War, 1899–1902". Retrieved 30 March 2008.

- Karnow, Stanley. "Two Nations". PBS. Retrieved 31 March 2008.

- Lichauco and Storey, The Conquest of the Philippines by the United States, 1898–1925, p. 120.

- ^ Gedacht, Joshua. "Mohammedan Religion Made It Necessary to Fire:" Massacres on the American Imperial Frontier from South Dakota to the Southern Philippines," in Colonial Crucible: Empire in the Making of the Modern American State. Edited by Alfred W. McCoy and Francisco A. Scarano. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 2009, pp. 397-409.

- ^ The Battle of Bud Dajo (archived from the original Archived May 9, 2008, at the Wayback Machine on 2008-05-09), chapter 19 of Swish of the Kris (archived from the original Archived February 2, 2008, at the Wayback Machine on 2008-02-02), by Vic Hurley.

- ^ Lane, Jack C. (1978). Armed Progressive: General Leonard Wood. Presidio Press. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-89141-009-6.

- ^ Jones, Gregg (2013). Honor in the Dust: Theodore Roosevelt, War in the Philippines, and the Rise and Fall of America's Imperial Dream. New American Library. pp. 353–354, 420. ISBN 978-0-451-23918-1.

- The statement from Scott comes from: Gedacht, Joshua. "Mohammedan Religion Made It Necessary to Fire:" Massacres on the American Imperial Frontier from South Dakota to the Southern Philippines". In Colonial Crucible: Empire in the Making of the Modern American State. Edited by Alfred W. McCoy and Francisco A. Scarano. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 2009, pp. 397–409. Information on the use of craters as sites of refuge during Spanish attacks can be found in: Warren, James Francis. The Sulu Zone, 1768–1898: The Dynamics of External Trade, Slavery, and Ethnicity in the Transformation of a Southeast Asian Maritime State, 2nd ed. Singapore: NUS Press, 2007.

- Hurley, Vic; Harris, Christopher L. (October 2010). Swish of the Kris, the Story of the Moros. ISBN 9780615382425.

- Mark Twain (17 November 2013). Delphi Complete Works of Mark Twain (Illustrated). Delphi Classics. p. 3819. ISBN 978-1-908909-12-1.

- Mark Twain (17 November 2013). Delphi Complete Works of Mark Twain (Illustrated). Delphi Classics. pp. 3777–. ISBN 978-1-908909-12-1.

- Twain, Mark (22 July 2017). Comments on the Moro Massacre. ISBN 9788026878148.

- Hagedorn, Hermann (1931). Leonard Wood: A Biography. London. p. 64.

- "U.S. Invasion and Occupation of Haiti, 1915–34". United States Department of State. 13 July 2007. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- ^ Belleau, Jean-Philippe (25 January 2016). "Massacres perpetrated in the 20th Century in Haiti". Sciences Po. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- Hans Schmidt (1971). The United States Occupation of Haiti, 1915–1934. Rutgers University Press. p. 102. ISBN 9780813522036.

- Farmer, Paul (2003). The Uses of Haiti. Common Courage Press. p. 98.

- Lockwood, Charles (1951). Sink 'em All. Bataam Books. ISBN 978-0-553-23919-5.

- O'Kane, Richard (1987). Wahoo: The Patrols of America's Most Famous WWII Submarine. Presidio Press. ISBN 978-0-89141-301-1.

- Blair, Clay (2001). Silent Victory. ISBN 978-1-55750-217-9.

- Holwitt 2005, p. 288; DeRose 2000, pp. 287–288.

- Holwitt 2005, p. 289; DeRose 2000, pp. 77, 94.

- ^ Gillison, Douglas (1962). Royal Australian Air Force 1939–1942. Canberra: Australian War Memorial.

- johnston, mark (2011). Whispering Death: Australian Airmen in the Pacific War. Crows Nest, New South Wales: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-74175-901-3.

- Ben Fenton, "American troops 'murdered Japanese PoWs'" (Daily Telegraph (UK), 06/08/2005), accessed 26/05/2007.

- John W. Dower, 1986, War Without Mercy, p.69.

- Ben Fenton, "American troops 'murdered Japanese PoWs'" (Daily Telegraph (UK), 06/08/2005), accessed 26/05/2007

- ^ Ferguson, Niall (2004). "Prisoner Taking and Prisoner Killing in the Age of Total War: Towards a Political Economy of Military Defeat". War in History. 11 (2): 148–192. doi:10.1191/0968344504wh291oa. JSTOR 26061867. S2CID 159610355.

- ^ Straus, Ulrich (2003). The Anguish Of Surrender: Japanese POWs of World War II. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 9780295983363.

- "The Avalon Prject - Laws of War : Laws and Customs of War on Land (Hague IV); October 18, 1907". avalon.law.yale.edu.

- Weingartner, James J. (1992). "Trophies of War: U.S. Troops and the Mutilation of Japanese War Dead, 1941-1945". Pacific Historical Review. 61 (1): 53–67. doi:10.2307/3640788. JSTOR 3640788.

- * Weingartner, James J. (February 1992). "Trophies of War: U.S. Troops and the Mutilation of Japanese War Dead, 1941-1945". Pacific Historical Review. 61 (1): 53–67. doi:10.2307/3640788. JSTOR 3640788. Archived from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 11 August 2011.

U.S. Marines on their way to Guadalcanal relished the prospect of making necklaces of Japanese gold teeth and "pickling" Japanese ears" as keepsakes.

- ^ Harrison, Simon (2006). "Skull Trophies of the Pacific War: transgressive objects of remembrance". Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute. 12 (4): 817–836. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9655.2006.00365.x.

- Dickey, Colin (2012). Afterlives of the Saints: Stories from the Ends of Faith. ISBN 9781609530723.

- ^ Schrijvers, Peter (2002). The GI War Against Japan. New York: New York University Press. p. 212. ISBN 978-0-8147-9816-4.

- Tanaka, Toshiyuki. Japan's Comfort Women: Sexual Slavery and Prostitution During World War II, Routledge, 2003, p.111. ISBN 0-203-30275-3

- Sims, Calvin (1 June 2000). "3 Dead Marines and a Secret of Wartime Okinawa". The New York Times. Nago, Japan. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

Still, the villagers' tale of a dark, long-kept secret has refocused attention on what historians say is one of the most widely ignored crimes of the war, the widespread rape of Okinawan women by American servicemen.

- ^ Sims, Calvin (1 June 2000). "3 Dead Marines and a Secret of Wartime Okinawa". The New York Times. Nago, Japan. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- Feifer, George (1992). Tennozan: The Battle of Okinawa and the Atomic Bomb. Michigan: Ticknor & Fields. ISBN 9780395599242.

- Molasky, Michael S. (1999). The American Occupation of Japan and Okinawa: Literature and Memory. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-415-19194-4.

- Molasky, Michael S.; Rabson, Steve (2000). Southern Exposure: Modern Japanese Literature from Okinawa. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-8248-2300-9.

- Sheehan, Susan D; Elizabeth, Laura; Selden, Hein Mark. "Islands of Discontent: Okinawan Responses to Japanese and American Power": 18.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Walsh, Brian (October 2018). "Sexual Violence During the Occupation of Japan". The Journal of Military History. 82 (4): 1217–1219.

- Fabrizio Carloni (April 2009). Le atrocità alleate in Sicilia. Storia e battaglie. p. 13.

- "I CRIMINI DEGLI ALLEATI IN SICILIA E A NAPOLI NELLA SECONDA GUERRA MONDIALE – IL RUOLO DELLA MAFIA E QUELLO DELLA MASSONERIA".

- Giovanni Bartolone, Le altre stragi: Le stragi alleate e tedesche nella Sicilia del 1943–1944

- Weingartner, James J. A Peculiar Crusadee: Willis M. Everett and the Malmedy massacre, NYU Press, 2000, p. 118. ISBN 0-8147-9366-5

- James J. Weingartner, "Massacre at Biscari: Patton and an American War Crime", Historian, Volume 52 Issue 1, Pages 24–39, 23 Aug 2007

- ^ The Horror of D-Day: A New Openness to Discussing Allied War Crimes in WWII, Spiegel Online, 05/04/2010, (part 2), accessed 2010-07-08

- ^ The Horror of D-Day: A New Openness to Discussing Allied War Crimes in WWII, Spiegel Online, 05/04/2010, (part 1), accessed 2010-07-08

- Bradley A. Thayer, Darwin and international relations p.186

- Bradley A. Thayer, Darwin and international relations p.189

- Bradley A. Thayer, Darwin and international relations p.190

- Lundeberg, Philip K. (1994). "Operation Teardrop Revisited". In Runyan, Timothy J.; Copes, Jan M (eds.). To Die Gallantly: The Battle of the Atlantic. Boulder: Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-8133-8815-1., pp. 221–226; Blair, Clay (1998). Hitler's U-Boat War. The Hunted, 1942–1945 (Modern Library ed.). New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-679-64033-2., p. 687.

- Brandt (2004), I Heard You Paint Houses, p. 50

- Brandt (2004), p. 84.

- Brandt (2004), p. 52.

- Brandt (2004), p. 51.

- David Wilson (27 March 2007). "The secret war". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 22 November 2008.

- Lilly, Robert J. (2007). Taken by Force: Rape and American GIs in Europe During World War II. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-50647-3.

- Morrow, John H. (October 2008). "Taken by Force: Rape and American GIs in Europe during World War II By J. Robert Lilly". The Journal of Military History. 72 (4): 1324. doi:10.1353/jmh.0.0151. S2CID 162399427.

- Schofield, Hugh (5 June 2009). "Revisionists challenge D-Day story". BBC News. Retrieved 6 January 2010.

- Committee for the Review and Restoration of Honor for the No Gun Ri Victims (2009). No Gun Ri Incident Victim Review Report. Seoul: Government of the Republic of Korea. pp. 247–249, 328, 278. ISBN 978-89-957925-1-3.

- Lee, B-C (15 October 2012). "No Gun Ri Foundation held special law seminar". Newsis (online news agency) (in Korean). Retrieved 18 February 2020.

- Choe, Sang-Hun; Hanley, Charles J.; Mendoza, Martha (29 September 1999). "War's hidden chapter: Ex-GIs tell of killing Korean refugees". The Associated Press. Retrieved 18 June 2021 – via pulitzer.org.

- Rummel 1997 Lines 613]

- Valentino, Benjamin (2005). Final Solutions: Mass Killing and Genocide in the 20th Century. Cornell University Press. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-8014-7273-2.

- ^ Solis, Gary (1989). Marines And Military Law In Vietnam: Trial By Fire (PDF). History and Museums Division, United States Marine Corps. ISBN 978-1494297602.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- "Free Fire Zone – The Vietnam War". The Vietnam War. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- Lewis M. Simons. "Free Fire Zones". Crimes of War. Archived from the original on 19 October 2016. Retrieved 5 October 2016.

- Turse, Nick (2013). Kill Anything That Moves: The Real American War in Vietnam. Metropolitan Books. ISBN 978-0-8050-8691-1.

- Summary report from the report of General Peers Archived 2000-01-25 at the Wayback Machine.

- Department of the Army. Report of the Department of the Army Review of the Preliminary Investigations into the My Lai Incident (The Peers Report Archived 2008-11-15 at the Wayback Machine), Volumes I-III (1970).

- "Moral Courage In Combat: The My Lai Story" (PDF). USNA Lecture. 2003.

- "Obituaries: My Lai Pilot Hugh Thompson". All Things Considered. NPR. 6 January 2006. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- Nick Turse; Deborah Nelson (6 August 2006). "Civilian Killings Went Unpunished". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

- Deborah Nelson (14 August 2006). "Vietnam, The War Crimes Files". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- Buckley, Kevin (19 June 1972). "Pacification's Deadly Price". Newsweek. pp. 42–3.

- Sullivan, Patricia (5 August 2009). "Julian J. Ewell, 93, Dies; Decorated General Led Forces in Vietnam". Washington Post.

- Hammond, William (1996). The U.S. Army in Vietnam Public Affairs The Military and the Media 1968-1973. U.S. Army Center of Military History. p. 238. ISBN 978-0160486968.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- Guenter Lewy, America in Vietnam (New York: Oxford University Press, 1978), p. 283

- Colby, William (1978). Honorable Men: My Life in the CIA. Simon & Schuster; First edition (May 15, 1978)

- ^ Ward, Geoffrey C.; Burns, Ken (2017). The Vietnam War: An Intimate History. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 9781524733100.

- Sallah, Michael; Weiss, Mitch (2006). Tiger Force: A True Story of Men and War. Little, Brown and Company. pp. 22–23. ISBN 0316159972.

- Writer, TERI FIGUEROA-Staff. "Reduced sentences possible for war-crime convictions". courant.com. Retrieved 1 April 2022.

- Normand Poirier (August 1969). "An American Atrocity". Esquire Magazine. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- ^ Tucker, Spencer C. (20 May 2011). The Encyclopedia of the Vietnam War: A Political, Social, and Military History, 2nd Edition [4 volumes]: A Political, Social, and Military History. ABC-CLIO. p. 1054. ISBN 9781851099610.

- "1971 Command History Volume II" (PDF). United States Military Assistance Command Vietnam. p. J-21. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 July 2019. Retrieved 18 January 2015.

- Prisoner abuse

- Command's Responsibility: Detainee Deaths in U.S. Custody in Iraq and Afghanistan Archived October 2, 2006, at the Wayback Machine by Human Rights First

- Command Responsibility? Archived 2009-09-10 at the Wayback Machine by Jeremy Brecher and Brendan Smith, Published by Foreign Policy In Focus (FPIF), a joint project of the International Relations Center (IRC, online at www.irc-online.org) and the Institute for Policy Studies (IPS, online at www.ips-dc.org), January 10, 2006

- ^ Paust, Jordan J. (20 May 2005). "Executive Plans and Authorizations to Violate International Law Concerning Treatment and Interrogation of Detainees" (PDF). Columbia Journal of Transnational Law. 43: 811. SSRN 903349. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 September 2006.

- Shapiro, Walter (23 February 2006). "Parsing pain". Salon. Archived from the original on 7 March 2008.

- War Crimes warnings

- Holtzman, Elizabeth (28 June 2005). "Torture and Accountability". The Nation.

- Former NY Congress member Holtzman Calls For President Bush and His Senior Staff To Be Held Accountable for Abu Ghraib Torture Archived 2007-11-14 at the Wayback Machine Thursday, June 30, 2005 on Democracy Now

- Memos Reveal War Crimes Warnings By Michael Isikoff Newsweek May 19, 2004

- US Lawyers Warn Bush on War Crimes Global Policy Forum January 28, 2003

- The Gitmo Fallout: The fight over the Hamdan ruling heats up—as fears about its reach escalate. Archived May 12, 2007, at the Wayback Machine By Michael Isikoff and Stuart Taylor Jr., Newsweek, July 17, 2006

- Getting Away with Torture? Command Responsibility for the U.S. Abuse of Detainees Human Rights Watch, April 2005 Vol. 17, No. 1

- U.S.: Rumsfeld Potentially Liable for Torture Defense Secretary Allegedly Involved in Abusive Interrogation Human Rights Watch, April 14, 2006

- Charges Sought Against Rumsfeld Over Prison Abuse By ADAM ZAGORIN, Time

- War Crimes Suit Prepared against Rumsfeld Archived 2007-11-14 at the Wayback Machine Democracy Now, November 9th, 2006

- War Criminals, Beware Archived 2006-11-20 at the Wayback Machine by Jeremy Brecher and Brendan Smith, The Nation, November 3, 2006

- Pushing Back on Detainee Act by Michael Ratner is president of the Center for Constitutional Rights, The Nation, October 4, 2006

- Military Commissions Act of 2006

- Why The Military Commissions Act is No Moderate Compromise By MICHAEL C. DORF, FindLaw, Oct. 11, 2006

- The CIA, the MCA, and Detainee Abuse By JOANNE MARINER, FindLaw, November 8, 2006

- Europe's Investigations of the CIA's Crimes By JOANNE MARINER, FindLaw, February 20, 2007

- Nat Hentoff (8 December 2006). "Bush's War Crimes Cover-up". Village Voice. Archived from the original on 17 June 2008. Retrieved 2 April 2007.

- Court 'can envisage' Blair prosecution By Gethin Chamberlain, Sunday Telegraph, March 17, 2007

- Coalition for the International Criminal Court, 18 July 2008. "States Parties to the Rome Statute of the ICC" (PDF). Archived from the original on 9 June 2019. Retrieved 12 November 2010.. Accessed 12 November 2010.

- Overseas, Expectations Build for Torture Prosecutions By Scott Horton, No Comment, January 19, 2009

- Die leere Anklagebank – Heikles juristisches Erbe: Der künftige US-Präsident Barack Obama muss über eine Strafverfolgung seiner Vorgänger entscheiden. Mögliche Angeklagte sind George W. Bush und Donald Rumsfeld. Archived 2009-02-25 at the Wayback Machine

- Von Wolfgang Kaleck Süddeutschen Zeitung, January 19, 2009 (German)

- ^ Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment calls for prosecution

- UN torture investigator calls on Obama to charge Bush for Guantanamo abuses Ximena Marinero, JURIST, January 21, 2009

- UN Rapporteur: Initiate criminal proceedings against Bush and Rumsfeld now By Scott Horton, No Comment, January 21, 2009

- ^ Library, C. N. N. (30 October 2013). "Haditha Killings Fast Facts". CNN. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- "Marine gets no jail time for Haditha killings". www.cbsnews.com. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- Schmitt, Eric (8 July 2006). "General finds senior Marines lax in Haditha killings probe". Chicago Tribune.

Sources

- DeRose, James F. (2000), Unrestricted Warfare, John Wiley & Sons

- Holwitt, Joel I. (2005), Execute Against Japan, Ohio State University PhD dissertation.

Further reading

General

- Jeremy Brecher; Jill Cutler; Brendan Smith, eds. (2005). In the name of democracy: American war crimes in Iraq and beyond. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-8050-7969-2.

- Michael Haas (2008). George W. Bush, war criminal?: the Bush administration's liability for 269 war crimes. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-36499-0.

- Jordan J. Paust (2007). Beyond the law: the Bush Administration's unlawful responses in the "War" on Terror. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-71120-3.

- Mark Selden; Alvin Y. So, eds. (2004). War and state terrorism: the United States, Japan, and the Asia-Pacific in the long twentieth century. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7425-2391-3.

- Frederick Henry Gareau (2004). State terrorism and the United States: from counterinsurgency to the war on terrorism. Zed Books. ISBN 978-1-84277-535-6.

- Vincent Bugliosi (2008). The Prosecution of George W. Bush for Murder. Vanguard. ISBN 978-1-59315-481-3.

- "Leave No Marks: Enhanced Interrogation Techniques and the Risk of Criminality" (PDF). Physicians for Human Rights / Human Rights First. August 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 August 2010. Retrieved 17 August 2010.

By nation

- Iraq

- Richard A. Falk; Irene L. Gendzier; Robert Jay Lifton, eds. (2006). Crimes of war: Iraq. Nation Books. ISBN 978-1-56025-803-2.

- Ramsey Clark (1992). War crimes: a report on United States war crimes against Iraq. Maisonneuve Press. ISBN 978-0-944624-15-9.

- Nafeez Mosaddeq Ahmed (2003). Behind the war on terror: western secret strategy and the struggle for Iraq. New Society Publishers. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-86571-506-6.

- Marjorie Cohn (9 November 2006). "Donald Rumsfeld: The War Crimes Case". The Jurist.

- Ulrike Demmer (26 March 2007). "Wanted For War Crimes: Rumsfeld Lawsuit Embarrasses German Authorities". Der Spiegel.

- Patrick Donahue (27 April 2007). "German Prosecutor Won't Set Rumsfeld Probe Following Complaint". Bloomberg L.P.

- Vietnam

- Greiner, Bernd; Anne Wyburd (2009). War Without Fronts: The USA in Vietnam. New Haven, Conn: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-15451-1.

- Deborah Nelson (2008). The war behind me: Vietnam veterans confront the truth about U.S. war crimes. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-00527-7.

- Nick Turse (2013). Kill Anything That Moves: The Real American War in Vietnam. New York: Metropolitan Books. ISBN 978-0-8050-8691-1.

External links

- Human Rights First; Command’s Responsibility: Detainee Deaths in U.S. Custody in Iraq and Afghanistan