| Revision as of 19:11, 27 August 2022 editThoughtIdRetired (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users9,305 edits →History: alternative history← Previous edit | Revision as of 07:14, 28 August 2022 edit undoThoughtIdRetired (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users9,305 edits This book has been reviewed as containing "many errors of fact, misleading simplification of material and references that are frequently inadequate, inappropriate or dated.". See Barbara Watson Andaya in Crossroads: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Southeast Asian Studies Vol. 10, No. 1 (1996), pp. 152-155. Therefore, as per WP:HSC, this in not an RS. See https://www.jstor.org/stable/40860555|date=June 2022Next edit → | ||

| Line 31: | Line 31: | ||

| Austronesians traditionally made their sails from woven mats of the resilient and salt-resistant ] leaves. These sails allowed Austronesians to embark on long-distance voyaging. In some cases, however, they were one-way voyages. The failure of pandanus to establish populations in ] and ] is believed to have isolated their settlements from the rest of Polynesia.<ref name="Kirch2012">{{cite book|first1=Patrick Vinton|last1=Kirch|title =A Shark Going Inland Is My Chief: The Island Civilization of Ancient Hawai'i|publisher =University of California Press|year =2012|pages=25–26|isbn = 9780520953833|url =https://books.google.com/books?id=CDQy8OOicF4C&pg=PA25}}</ref><ref name="Gallaher2014">{{cite book|first1=Timothy|last1=Gallaher|editor1-first=Lia O'Neill M.A.|editor1-last=Keawe|editor2-first=Marsha|editor2-last=MacDowell|editor3-first=C. Kurt|editor3-last=Dewhurst|title =ʻIke Ulana Lau Hala: The Vitality and Vibrancy of Lau Hala Weaving Traditions in Hawaiʻi|chapter =The Past and Future of Hala (''Pandanus tectorius'') in Hawaii|publisher =Hawai'inuiakea School of Hawaiian Knowledge ; University of Hawai'i Press |year =2014|doi= 10.13140/RG.2.1.2571.4648|isbn =9780824840938 |url =https://www.researchgate.net/publication/276291081}}</ref> | Austronesians traditionally made their sails from woven mats of the resilient and salt-resistant ] leaves. These sails allowed Austronesians to embark on long-distance voyaging. In some cases, however, they were one-way voyages. The failure of pandanus to establish populations in ] and ] is believed to have isolated their settlements from the rest of Polynesia.<ref name="Kirch2012">{{cite book|first1=Patrick Vinton|last1=Kirch|title =A Shark Going Inland Is My Chief: The Island Civilization of Ancient Hawai'i|publisher =University of California Press|year =2012|pages=25–26|isbn = 9780520953833|url =https://books.google.com/books?id=CDQy8OOicF4C&pg=PA25}}</ref><ref name="Gallaher2014">{{cite book|first1=Timothy|last1=Gallaher|editor1-first=Lia O'Neill M.A.|editor1-last=Keawe|editor2-first=Marsha|editor2-last=MacDowell|editor3-first=C. Kurt|editor3-last=Dewhurst|title =ʻIke Ulana Lau Hala: The Vitality and Vibrancy of Lau Hala Weaving Traditions in Hawaiʻi|chapter =The Past and Future of Hala (''Pandanus tectorius'') in Hawaii|publisher =Hawai'inuiakea School of Hawaiian Knowledge ; University of Hawai'i Press |year =2014|doi= 10.13140/RG.2.1.2571.4648|isbn =9780824840938 |url =https://www.researchgate.net/publication/276291081}}</ref> | ||

| Because of the crab claw sail's more ancient origin, there is also a hypothesis that contact between ] and Austronesians in their Indian Ocean voyages may have influenced the development of the triangular Arabic ] sail; and in return Arab square-shaped sails may have influenced the development of the Austronesian rectangular ] of western Southeast Asia.<ref name="Mahdi1999">{{cite book|author=Mahdi, Waruno |editor=Blench, Roger |editor2=Spriggs, Matthew|title =Archaeology and Language III: Artefacts languages, and texts|chapter =The Dispersal of Austronesian boat forms in the Indian Ocean|volume = 34|publisher =Routledge|series =One World Archaeology |year =1999|page=144-179|isbn =0415100542}}</ref> Others, however, believe that the tanja sail was an indigenous invention of Southeast Asian Austronesians, though they also believe that the lateen sail may have been introduced to Arab sailors via contact with Austronesian crab claw sails. |

Because of the crab claw sail's more ancient origin, there is also a hypothesis that contact between ] and Austronesians in their Indian Ocean voyages may have influenced the development of the triangular Arabic ] sail; and in return Arab square-shaped sails may have influenced the development of the Austronesian rectangular ] of western Southeast Asia.<ref name="Mahdi1999">{{cite book|author=Mahdi, Waruno |editor=Blench, Roger |editor2=Spriggs, Matthew|title =Archaeology and Language III: Artefacts languages, and texts|chapter =The Dispersal of Austronesian boat forms in the Indian Ocean|volume = 34|publisher =Routledge|series =One World Archaeology |year =1999|page=144-179|isbn =0415100542}}</ref> Others, however, believe that the tanja sail was an indigenous invention of Southeast Asian Austronesians, though they also believe that the lateen sail may have been introduced to Arab sailors via contact with Austronesian crab claw sails.<ref name="Hourani 1951">{{Cite book|title=Arab Seafaring in the Indian Ocean in Ancient and Early Medieval Times|last=Hourani|first=George Fadlo|publisher=Princeton University Press|year=1951|location=New Jersey}}</ref><ref name="Johnstone 1980">{{Cite book|title=The Seacraft of Prehistory|last=Johnstone|first=Paul|publisher=Harvard University Press|year=1980|isbn=978-0674795952|location=Cambridge}}</ref> A third theory however, concludes that lateen sails were originally Mediterranean and that ] sailors introduced the lateen sail to Asian waters, starting with ]'s arrival in ] in 1500. This means that the development of lateen sails in western sailors were not influenced by the crab claw sail.<ref>{{Cite book|last=White|first=Lynn|title=Medieval Religion and Technology. Collected Essays|publisher=University of California Press|year=1978|isbn=978-0-520-03566-9}}</ref>{{Rp|257f}} | ||

| In western ], the crab claw sail reappeared as a recent development. Traditionally the people from Nusantara archipelago had shifted to the tanja sail, but starting in the 19th century the ] developed the lete sail. "''Lete''" actually means lateen, but the existence of ''pekaki'' (lower spar/boom) indicates that the ''layar lete'' is crab claw sail.<ref>{{Cite book|title=The Prahu: Traditional Sailingboat of Indonesia|last=Horridge|first=Adrian|publisher=Oxford University Press|year=1981|location=Oxford}}</ref> | In western ], the crab claw sail reappeared as a recent development. Traditionally the people from Nusantara archipelago had shifted to the tanja sail, but starting in the 19th century the ] developed the lete sail. "''Lete''" actually means lateen, but the existence of ''pekaki'' (lower spar/boom) indicates that the ''layar lete'' is crab claw sail.<ref>{{Cite book|title=The Prahu: Traditional Sailingboat of Indonesia|last=Horridge|first=Adrian|publisher=Oxford University Press|year=1981|location=Oxford}}</ref> | ||

Revision as of 07:14, 28 August 2022

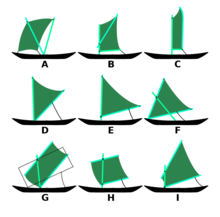

Triangular sail with spars along upper and lower edges used by traditional Austronesians

- Double sprit (Sri Lanka)

- Common sprit (Philippines)

- Oceanic sprit (Tahiti)

- Oceanic sprit (Marquesas)

- Oceanic sprit (Philippines)

- Crane sprit (Marshall Islands)

- Rectangular boom lug (Maluku Islands)

- Square boom lug (Gulf of Thailand)

- Trapezial boom lug (Vietnam)

The crab claw sail is a fore-and-aft triangular sail with spars along upper and lower edges. The crab claw sail was first developed by the Austronesian peoples some time around 1500 BC. It is used in many traditional Austronesian cultures in Island Southeast Asia, Micronesia, Island Melanesia, Polynesia, and Madagascar. Due to its extraordinary performance and ease of operation, it has also become very popular in modern sport sailing. It is sometimes known as the Oceanic lateen or the Oceanic sprit, even though it is not restricted to Oceania, is neither a lateen sail nor a spritsail, and has an independent older origin.

History

Crab-claw sails were invented by the Austronesians somewhere in Island Southeast Asia at no later than 1500 BCE. It was derived from a more ancient mast-less V-shaped square rig consisting simply of a square or triangular sail on two spars perpendicular to the hull converging at the base. It spread with the Austronesian migration to Micronesia, Island Melanesia, Madagascar, and Polynesia. It may have also caused the unique development of outrigger boat technology due to the necessity for stability once crab claw sails were attached to small watercraft. Crab claw sails can be used for double-canoe (catamaran), single-outrigger (on the windward side), or double-outrigger boat configurations, in addition to monohulls.

Crab claw sails are rigged fore-and-aft and can be tilted and rotated relative to the wind. They evolved from "V"-shaped perpendicular square sails (a "double sprit") in which the two spars converge at the base of the hull. The simplest form of the crab claw sail (also with the widest distribution) is composed of a triangular sail supported by two light spars (sometimes erroneously called "sprits") on each side. They were originally mastless, and the entire assembly was taken down when the sails were lowered. There are several distinct types of crab claw rigs, but unlike western rigs, they do not have fixed conventional names.

The need to propel larger and more heavily laden boats led to the increase in vertical sail. However this introduced more instability to the vessels. In addition to the unique invention of outriggers to solve this, the sails were also leaned backwards and the converging point moved further forward on the hull. This new configuration required a loose "prop" in the middle of the hull to hold the spars up, as well as rope supports on the windward side. This allowed more sail area (and thus more power) while keeping the center of effort low and thus making the boats more stable. The prop was later converted into fixed or removable canted masts where the spars of the sails were actually suspended by a halyard from the masthead. This type of sail is most refined in Micronesian proas which could reach very high speeds. These configurations are sometimes known as the "crane sprit" or the "crane spritsail". Micronesian, Island Melanesian, and Polynesian single-outrigger vessels also used this canted mast configuration to uniquely develop shunting, where canoes are symmetrical from front to back and change end-to-end when sailing against the wind.

The conversion of the prop to a fixed mast led to the much later invention of the tanja sail (also known variously and misleadingly as the canted square sail, canted rectangular sail, boomed lugsail, or balance lugsail). Tanja sails were rigged similarly to crab claw sails and also had spars on both the head and the foot of the sails; but they were square or rectangular with the spars not converging into a point.

Another evolution of the basic crab claw sail is the conversion of the upper spar into a fixed mast. In Polynesia, this gave the sail more height while also making it narrower, giving it a shape reminiscent of crab pincers (hence "crab claw" sail). This was also usually accompanied by the lower spar becoming more curved.

Austronesians traditionally made their sails from woven mats of the resilient and salt-resistant pandanus leaves. These sails allowed Austronesians to embark on long-distance voyaging. In some cases, however, they were one-way voyages. The failure of pandanus to establish populations in Easter Island and New Zealand is believed to have isolated their settlements from the rest of Polynesia.

Because of the crab claw sail's more ancient origin, there is also a hypothesis that contact between Arabs and Austronesians in their Indian Ocean voyages may have influenced the development of the triangular Arabic lateen sail; and in return Arab square-shaped sails may have influenced the development of the Austronesian rectangular tanja sail of western Southeast Asia. Others, however, believe that the tanja sail was an indigenous invention of Southeast Asian Austronesians, though they also believe that the lateen sail may have been introduced to Arab sailors via contact with Austronesian crab claw sails. A third theory however, concludes that lateen sails were originally Mediterranean and that Portuguese sailors introduced the lateen sail to Asian waters, starting with Vasco da Gama's arrival in India in 1500. This means that the development of lateen sails in western sailors were not influenced by the crab claw sail.

In western Indonesia, the crab claw sail reappeared as a recent development. Traditionally the people from Nusantara archipelago had shifted to the tanja sail, but starting in the 19th century the Madurese people developed the lete sail. "Lete" actually means lateen, but the existence of pekaki (lower spar/boom) indicates that the layar lete is crab claw sail.

Alternative history

The developmental history of Austronesian sailing rigs, particularly early windward-sailing capability is challenged by some working in the field. Atholl Anderson points out that there is little evidence of any of this maritime technology existing at the suggested points in prehistory. There is no archaeological or written evidence to support their early use – their existence has been argued on the basis that voyages of exploration and colonisation were made against the prevailing winds. This requires a rig that can sail to windward. Anderson (and others) argue that this "to windward" colonisation relies on occasional changes in the normal wind direction, often related to El Niño events. These were more common at the times in pre-history that coincide with phases of colonisation in new areas. Hence the early development of windward-sailing rigs is not a pre-requisite for the much of the Austronesian Expansion. Instead, using linguistic analysis of terms for elements of the more advanced Austronesian rigs, Anderson suggests that the primitive "mastless" rigs used by Austronesians were the only form until they encountered lateen technology in use by Arab sailing vessels of the 14th century. This is a complete reversal of the ideas of Campbell and others.

Construction

The crab claw sail consists of a sail, approximately an isosceles triangle in shape. The equal length sides are usually longer than the third side, with spars along the long sides.

The crab claw may also traditionally be constructed with curved spars, giving the edges of the sail along the spars a convex shape, while the leech of the sail is often quite concave to keep it stiff on the trailing edge. These features give it its distinct, claw-like shape. Modern crab claws generally have straighter spars and a less convex leech, which gives more sail area for a given length of spar. Spars may taper towards the leech. The structure helps the sail to spill gusts.

The crab claw characteristically widens upwards, putting more sail area higher above the ocean, where the wind is stronger and steadier. This increases the heeling moment: the sails tend to blow the watercraft over. For this reason, crab claws are typically used on multihulls, which resist heeling more strongly.

The sail is shunted; the bow becomes the stern, and the mast rake is also reversed. The vessel therefore always has the ama (and sidestay, if there is one) to windward, and has no bad tack.

-

V-shaped square rig from Melanesia, the direct precursor of crab claw sails

V-shaped square rig from Melanesia, the direct precursor of crab claw sails

-

"Crane sprit" type crab claw rig of Micronesia with a loose prop

"Crane sprit" type crab claw rig of Micronesia with a loose prop

-

"Crane sprit" type crab claw rig of the Philippines with a fixed mast

"Crane sprit" type crab claw rig of the Philippines with a fixed mast

-

Forward-mounted crab claw rig from the Duff Islands

Forward-mounted crab claw rig from the Duff Islands

-

New Guinea-style crab claw rig with vertical sails

New Guinea-style crab claw rig with vertical sails

-

Hawaiian crab claw rig amalgamating the upper spar into the fixed mast

Hawaiian crab claw rig amalgamating the upper spar into the fixed mast

Proa

In a proa, the forward intersection of the spars is placed towards the bow. The sail is supported by a short mast attached near the middle of the upper spar, and the forward corner is attached to the hull. The lower spar, or boom, is attached at the forward intersection, but is not attached to the mast. The proa has a permanent windward and leeward side, and exchanges one end for the other when coming about.

To tack, or switch directions across the wind, the forward corner of the sail is loosened and then transferred to the opposite end of the boat, a process called shunting. To shunt, the proa's sheet is let out. The joined corner of the spars is then transferred to the opposite end of the boat. While remaining attached to the top of the mast, the upper spar tilts to vertical and beyond as the forward corner moves past the mast and onward to the other end of the boat. Meanwhile, the mainsheet is detached and used to rotate the rearward end of the boom through a horizontal half circle. The spar join is then re-attached at the new "forward" end of the boat and the mainsheet is re-tightened at the new "rearward" end.

Tepukei

A shunting rig with the sail propped vertically at the bow, very similar to the proa rig described above.

Non-shunting crab claw

-

Hokule'a, a bluewater waʻa kaulua, with curved-spar, curved-leech crab claw sails, in 1976.

Hokule'a, a bluewater waʻa kaulua, with curved-spar, curved-leech crab claw sails, in 1976.

-

Hokule'a with her kaula pe'a (sail lines) tightened to partly close her crab-claw sails.

Hokule'a with her kaula pe'a (sail lines) tightened to partly close her crab-claw sails.

The term "crab claw sail" is also used for non-shunting sails that widen upwards. The 'ōpe'a, the upper spar, is braced up so high that it is nearly parallel to the mast (as in a gunter rig). The paepae, the lower spar/boom, points well above the horizontal, unlike the boom of most gunter rigs and gaff rigs. The two spars can be brought together or pulled apart with control lines. The mast is fixed and stayed.

Performance

The crab claw sail is something of an enigma. It has been demonstrated to produce very large amounts of lift when reaching, and overall seems superior to any other simple sail plan (this discounts the use of specialised sails such as spinnakers). C. A. Marchaj, a researcher who has experimented extensively with both modern rigs for racing sailboats and traditional sailing rigs from around the world, has done wind tunnel testing of scale models of crab claw rigs. One popular but disputed theory is that the crab claw wing works like a delta wing, generating vortex lift. Since the crab claw does not lie symmetrically to the airflow, like an aircraft delta wing, but rather lies with the lower spar nearly parallel to the water, the airflow is not symmetrical. However, the presence of the water, close to the lower spar and parallel to it, makes the airflow behave roughly like the airflow over half of a delta wing, as though a "reflection" in the water provided the other half (apart from a narrow gap near the water, which causes a small difference there).

This can clearly be seen in Marchaj's wind tunnel photos published in Sail Performance: Techniques to Maximise Sail Power (1996). The vortex on the top spar of the sail is much larger, covering most of the sail area, while the lower vortex is very small and stays close to the spar. Marchaj attributes the large lifting power of the sail to lift generated by the vortices, while others attribute the power to a favourable mix of aspect ratio, camber and (lack of) twist at this point of sail.

A more modern academic wind tunnel study (2014) provided similar results, with the Santa Cruz Islands tepukei's crab claw sail configuration dominating measurements.

Gallery

-

Carolinian wa with crab claw sail

Carolinian wa with crab claw sail

-

Sandeq boats in Majene, West Sulawesi, Indonesia

Sandeq boats in Majene, West Sulawesi, Indonesia

-

A proa in New Caledonia

-

Visayan paraw with a "crane sprit" crab claw sail

Visayan paraw with a "crane sprit" crab claw sail

-

Illustration of a crab claw sail in Tikehau (Louis Choris, 1816)

Illustration of a crab claw sail in Tikehau (Louis Choris, 1816)

-

Madurese golekan with crab claw sails

Madurese golekan with crab claw sails

-

1750 illustration of crab claw sail by George Anson

1750 illustration of crab claw sail by George Anson

See also

Related rigs

References

- Doran, Edwin B. (1981). Wangka: Austronesian Canoe Origins. Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 9780890961070.

- ^ Horridge A (2008). "Origins and Relationships of Pacific Canoes and Rigs" (PDF). In Di Piazza A, Pearthree E (eds.). Canoes of the Grand Ocean. BAR International Series 1802. Archaeopress. ISBN 9781407302898. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 22 October 2019.

- "Proa Rig Options: Crab Claw". Proafile. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ^ Campbell, I.C. (1995). "The Lateen Sail in World History". Journal of World History. 6 (1): 1–23. JSTOR 20078617.

- Lacsina, Ligaya (2016). Examining pre-colonial Southeast Asian boatbuilding: An archaeological study of the Butuan Boats and the use of edge-joined planking in local and regional construction techniques (PhD). Flinders University.

- ^ Horridge, Adrian (April 1986). "The Evolution of Pacific Canoe Rigs". The Journal of Pacific History. 21 (2): 83–99. doi:10.1080/00223348608572530. JSTOR 25168892.

- Kirch, Patrick Vinton (2012). A Shark Going Inland Is My Chief: The Island Civilization of Ancient Hawai'i. University of California Press. pp. 25–26. ISBN 9780520953833.

- Gallaher, Timothy (2014). "The Past and Future of Hala (Pandanus tectorius) in Hawaii". In Keawe, Lia O'Neill M.A.; MacDowell, Marsha; Dewhurst, C. Kurt (eds.). ʻIke Ulana Lau Hala: The Vitality and Vibrancy of Lau Hala Weaving Traditions in Hawaiʻi. Hawai'inuiakea School of Hawaiian Knowledge ; University of Hawai'i Press. doi:10.13140/RG.2.1.2571.4648. ISBN 9780824840938.

- Mahdi, Waruno (1999). "The Dispersal of Austronesian boat forms in the Indian Ocean". In Blench, Roger; Spriggs, Matthew (eds.). Archaeology and Language III: Artefacts languages, and texts. One World Archaeology. Vol. 34. Routledge. p. 144-179. ISBN 0415100542.

- Hourani, George Fadlo (1951). Arab Seafaring in the Indian Ocean in Ancient and Early Medieval Times. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Johnstone, Paul (1980). The Seacraft of Prehistory. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674795952.

- White, Lynn (1978). Medieval Religion and Technology. Collected Essays. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-03566-9.

- Horridge, Adrian (1981). The Prahu: Traditional Sailingboat of Indonesia. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Anderson, Atholl (2018). "SEAFARING IN REMOTE OCEANIA Traditionalism and Beyond in Maritime Technology and Migration". In Cochrane, Ethan E; Hunt, Terry L. (eds.). The Oxford handbook of prehistoric Oceania. New York, NY. ISBN 978 0 19 992507 0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Gross, Jeffrey L. (2016). Waipio Valley: A Polynesian Journey from Eden to Eden. Xlibris Corporation. p. 626. ISBN 9781479798469.

- "Proa Rig Options: Crab Claw". proafile.com. Proa File. July 23, 2014. Retrieved 2017-04-21.

- ^ "Parts of the Hawaiian Canoe". archive.hokulea.com. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- Star-Bulletin, Honolulu. "starbulletin.com - News - /2007/03/06/". archives.starbulletin.com. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- Hōkūle‘a Image Gallery (From 1973) archive.hokulea.com, accessed 12 February 2020

- Marchaj, C. A. (2003). Sail Performance: Techniques to Maximise Sail Power. ISBN 0-07-141310-3.

- Slotboom, Bernard. "Delta Sail in A "Wind Tunnel" Experiences". Experiences from B.J. Slotboom. Retrieved January 7, 2015.

- Anne Di Piazza, Erik Pearthree and Francois Paille (2014). "Wind Tunnel Measurements of the Performance of Canoe Sails from Oceania". Journal of the Polynesian Society.

External links

- Video "Hot Buoys" Self-Tacking Crab-Claw Trimaran

- Wind Tunnel results on effects of crabclaw sail orientation - apex position and consistent camber

| Types of sailing vessels and rigs | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overviews | |||||||||||||||||

| Sailing rigs | |||||||||||||||||

| By sailing rigs | |||||||||||||||||

| Multihull vessels | |||||||||||||||||

| Naval and merchant sailing ships and other vessels (by origin date) |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Fishing vessels | |||||||||||||||||

| Recreational vessels | |||||||||||||||||

| Special terms | |||||||||||||||||

| Other types | |||||||||||||||||

| Related | |||||||||||||||||

| Sails, spars and rigging | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| including limited use, outdated | |||||||

| Rigs |

| ||||||

| Sails (sailing rigs) |

| ||||||

| Spars |

| ||||||

| Rigging |

| ||||||