| Revision as of 23:56, 19 March 2005 editKevehs (talk | contribs)1,979 edits Removing more needless attempts to minimize meaning that some people don't like← Previous edit | Revision as of 03:21, 20 March 2005 edit undoHarry491 (talk | contribs)4,372 edits moved part of italics stuff at the beginning to the "terminology" section because the italics at the beginning was too longNext edit → | ||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

| ''For the use of the term "libertarianism" in the philosophy of ] see ].'' | ''For the use of the term "libertarianism" in the philosophy of ] see ].'' | ||

| ''"Libertarian" and "libertarianism" are also used to refer to liberty in a general way. For example, someone arguing for ] may be known as a "]," regardless of their exact political allegiances. |

''"Libertarian" and "libertarianism" are also used to refer to liberty in a general way. For example, someone arguing for ] may be known as a "]," regardless of their exact political allegiances. | ||

| == Introduction == | == Introduction == | ||

| Line 12: | Line 12: | ||

| == Terminology == | == Terminology == | ||

| The term "libertarianism" in the above sense has been in widespread use only since the ]. ''Libertaire'' had previously been used most commonly by ]s to describe themselves, avoiding the negative connotations of the word "]." After the suppression of the ] by the French government in ], anarchism and anarchists were officially outlawed, so anarchists often called their groups and publications by another name — hence the adoption of ''libertaire'' as an alternative term in French. In this formulation, libertarianism is a variant of ]. | The term "libertarianism" in the above sense has been in widespread use only since the ]. ''Libertaire'' had previously been used most commonly by ]s to describe themselves, avoiding the negative connotations of the word "]." After the suppression of the ] by the French government in ], anarchism and anarchists were officially outlawed, so anarchists often called their groups and publications by another name — hence the adoption of ''libertaire'' as an alternative term in French. In this formulation, libertarianism is a variant of ]. | ||

| In English, those who criticize all hierarchies, as opposed to only the state, are sometimes referred to as "libertarian," and are discussed in their own articles. For the most part, these groups choose to call themselves ]s, ]s, or ]s. Often, the word “libertarian” is applied to these groups with a qualifier such as “left-libertarian” or “libertarian socialist.” | |||

| The term "libertarian" as used here gained currency in the ] in the middle of the ], with thinkers who saw themselves as continuing the ] tradition of the ]. By that time, in the United States, contemporary ] supported ] of the ] and government ] of ], all of which these so-called “classical liberal” or "libertarian" individuals opposed. | The term "libertarian" as used here gained currency in the ] in the middle of the ], with thinkers who saw themselves as continuing the ] tradition of the ]. By that time, in the United States, contemporary ] supported ] of the ] and government ] of ], all of which these so-called “classical liberal” or "libertarian" individuals opposed. | ||

Revision as of 03:21, 20 March 2005

This article deals with libertarianism as often used in the United States, England, Australia, and Canada: opposition to state involvement in personal and economic decisions, and support of a right to acquire and protect private property. For a discussion of the term libertarian as often used in Europe, see libertarian socialism.

For the use of the term "libertarianism" in the philosophy of free will see libertarianism (philosophy).

"Libertarian" and "libertarianism" are also used to refer to liberty in a general way. For example, someone arguing for civil liberties may be known as a "civil libertarian," regardless of their exact political allegiances.

Introduction

Libertarianism is a political philosophy that advocates protection of individual liberty such that no individual or group (including the state) may act to diminish the liberty of any other individual; all other persons (including persons acting on behalf of governments) are to have complete freedom of action as long as they do not initiate the use of force (as distinct from force used in response to an initiation). For this purpose, “force” is defined by many libertarians as physical force, the threat of such, or fraud against the person or property of another. According to the U.S. Internal Revenue Service, "Libertarianism is a philosophy. The basic premise of libertarianism is that each individual should be free to do as he or she pleases so long as he or she does not harm others. In the libertarian view, societies and governments infringe on individual liberties whenever they tax wealth, create penalties for victimless crimes, or otherwise attempt to control or regulate individual conduct which harms or benefits no one except the individual who engages in it."

Terminology

The term "libertarianism" in the above sense has been in widespread use only since the 1950s. Libertaire had previously been used most commonly by anarchists to describe themselves, avoiding the negative connotations of the word "anarchy." After the suppression of the Paris Commune by the French government in 1871, anarchism and anarchists were officially outlawed, so anarchists often called their groups and publications by another name — hence the adoption of libertaire as an alternative term in French. In this formulation, libertarianism is a variant of socialism.

In English, those who criticize all hierarchies, as opposed to only the state, are sometimes referred to as "libertarian," and are discussed in their own articles. For the most part, these groups choose to call themselves anarchists, socialists, or anarcho-syndicalists. Often, the word “libertarian” is applied to these groups with a qualifier such as “left-libertarian” or “libertarian socialist.”

The term "libertarian" as used here gained currency in the United States in the middle of the 20th century, with thinkers who saw themselves as continuing the classical liberal tradition of the Enlightenment. By that time, in the United States, contemporary liberals supported regulation of the economy and government redistribution of wealth, all of which these so-called “classical liberal” or "libertarian" individuals opposed.

A typographical convention

Libertarianism is an ideology rather than a political party, hence when Libertarian is capitalized rather then spelled a lowercase "l" it refers specifically to a member of a party that titles itself a "Libertarian Party." This distinction is important because "Libertarian Parties" may not always be consistent with all forms of libertarianism. Therefore, some libertarians wish to make it known that they do not align themselves with a "Libertarian Party," due to some philosophical disagreements. Also, some libertarians may be members of other parties, such as U.S. Congressman Ron Paul who is a Republican.

Libertarianism and Classical Liberalism

As noted in the previous section, the latest incarnation of libertarians see their origins in the earlier 17th to 20th century tradition of classical liberalism, and often use that term as a synonym for libertarianism. The founding fathers of the U.S. were called "liberals" at the time, as they opposed the European restrictions on individual liberty --those guarding the status-quo being termed "conservatives" at the time. Thomas Jefferson was then considered a liberal, saying "the government that governs best, governs least." Since "liberalism," in America, now refers to something much different, others use the term "libertarian" rather than "liberal" to distance themselves from the socialist and welfare state connotations of the word "liberal" in American English. Some American libertarians call themselves "classical liberals" to emphasize this tradition while retaining the use of the word "liberal." Hayek and other scholars state that libertarianism today has few commonalities with modern "new" or "welfare" liberalism. This opposition is clearly explained in Friedrich Hayek's article "Why I Am Not a Conservative" (Hayek is referring there to European authoritarian Conservatism, which was suspicious of capitalism due to the belief that it undermined the power of the state). Internationally, however, some libertarian political parties adhere to the use of the term "liberal" such as ACT of New Zealand which refers itself as "the liberal party."

Some, particularly in the USA, argue that while libertarianism has much in common with the earlier tradition of classical liberalism, the latter term should be reserved for historical thinkers for the sake of clarity and accuracy. They may also assert that there is a patterned difference between many libertarian and classical liberal thinkers concerning limitations on state power. Additionally, many modern libertarians view the very wealthy as having earned their place, while, according to these critics, the classical liberals were often skeptical of the rich, businessmen, and corporations seeing them as aristocrats with desires to tyrannize the people. Perhaps the most important classical liberal of this strain was Thomas Jefferson who was critical of the growth of corporations, to which most modern libertarians would grant considerable freedom of action. Jefferson, along with some 19th and 20th century libertarians (and even some modern day Libertarians - see geolibertarian), also argued at times for a relatively loose concept of the right to property in land.

In any case, many libertarians see themselves as the inheritors of classical liberalism. Advocacy of free markets, free trade, limited government, a non-interventionist foreign policy and individual liberty are common themes of both libertarianism and classical liberalism. For some, libertarianism has a connotation of being isolationist and opposing interpersonal cooperation, however libertarians frequently cite the benefits of cooperating through trade rather than resorting to coercion to obtain goods and services.

Libertarianism in the modern political spectrum

Libertarians do not identify themselves as either "right-wing" or "left-wing," and reject the ideology of either of those wings. In the US some libertarians regard themselves as conservatives, as they claim their ideology closely resembles the ones of the founding fathers of the USA. Yet, some individuals equate conservative with the right-wing and use the terms interchangeably. Many libertarians maintain that this is a fallacious equivocation, reasoning that the ideology of the founders was not rightist (which libertarians often consider to be an ideology that supports restrictions on civil liberties).

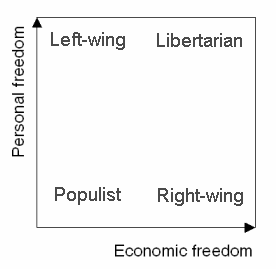

Libertarians tend to propose a two-dimensional space with "personal freedom" on one Cartesian axis and "economic freedom" on the other. This space is shown by the Nolan Chart, proposed by David Nolan, the founder of the United States Libertarian Party. Though many libertarians may believe the separation of personal and economic freedom is actually a false dichotomy, the Nolan Chart is frequently utilized in order to differentiate their ideology from others (e.g., conservativism and modern liberalism) which generally advocate greater limitations on different modes of freedom according to their respective conceptions of rights. The libertarian conception of rights is claimed to maximize individual liberty and autonomy, which leads libertarians to advocate what they believe are the fewest possible limitations on either mode of freedom. The validity of the Nolan Chart is disputed by many non-libertarians. Many argue that the libertarian definition of "freedom" is flawed or incorrect.

Further confusing the classification of libertarianism are attempts by other groups to claim its values as their own. A good example is this quotation from Ronald Reagan:

- "If you analyze it I believe the very heart and soul of conservatism is libertarianism. I think conservatism is really a misnomer just as liberalism is a misnomer for the liberals -- if we were back in the days of the Revolution, so-called conservatives today would be the Liberals and the liberals would be the Tories. The basis of conservatism is a desire for less government interference or less centralized authority or more individual freedom and this is a pretty general description also of what libertarianism is."

For more information, see main article: Nolan chart

Individualism, Liberty, Rights and Property

The fundamental values that libertarians claim to fight for are individual liberty, individual responsibility and individual property. Some libertarians have an elaborate theories of these values that they defend, that do not always match prevailing views regarding liberty, and that strictly opposes leftist, rightist, and collectivist views in this regard. Many libertarians hold that personal liberties (such as privacy and freedom of speech) and economic liberties (such as the freedom to trade, profit, labor, or invest) are both justifiable on the same philosophical or ethical foundations. On the other hand, many have no complex philosophical groundings for their espousal of libertarianism but simply like idea of having the freedoms that the ideology advocates. Libertarians contrast themselves with authoritarian leftists who believe that attenuation of economic liberty is necessary for personal freedom and personal well-being, with rightists who promote free markets and free trade but advocate restrictive regulation of personal issues such as sexuality, drug use, and speech, and with centrists who share moderate characterists of both the left and the right.

It is a chief tenet for many libertarians that rights rest originally in individuals and never in groups such as nations, races, religions, classes, or cultures. This conception holds it as nonsensical to say (for instance) that a wrong can be done to a class or a race in the absence of specific wrongs done to individual members of that group. It also undercuts rhetorical expressions such as, "The government has the right to ...", since under this formulation "the government" has no original rights but only those duties with which it has been lawfully entrusted under the citizens' rights. Libertarianism frequently dovetails neatly therefore with strict constructionism and the constitution in exile.

The classic problem in political philosophy of the legitimacy of property is essential to libertarians. Libertarians often justify individual property on the basis of self-ownership: a percieved right for one to own one's body; the results of one's own work; what one obtains from the voluntary concession of a former legitimate owner through trade, gift or inheritance, and so forth. Ownership of disputed natural resources is seen as more problematic and solutions such as homesteading have been studied from John Locke to Murray Rothbard. This is particularly important since many criticisms of private property rest on the notion that no person can claim rightful ownership over natural resources, and that since the making of any object requires some amount of raw materials and natural resources, no person can claim rightful ownership over man-made objects either. However, libertarian philosophers often maintain that if natural resources are initially unowned, then claiming and asserting ownership of them cannot properly be considered stealing and that, therefore, doing so is not wrongful. (finders keepers). An extreme example of ownership of natural resources is Free-market environmentalism which holds that the best way to protect the environment is to eliminate externalities by maximizing property ownership and minimizing the supposed tragedy of the commons.

Defining "Rights"

Most rights-focused libertarians would argue that the only "rights" that should be established are variants of "the right to be left alone" and that other "rights" such as "the right to a good education" or "the right to employment" are not rights and do not deserve the same protections. This is primarily a point of disagreement with liberal critics.

One way of describing the distinction is that "the right to be left alone by other people" is a negative right whereas the right to something is a positive right. The reasoning for rejecting positive rights is that a mandate that a person must be provided with something by the action of another is not logically compatible with a right that mandates that individuals be allowed to do they wish. Some non-libertarians find the distinction blurry or reject the distinction altogether.

Opposition to Statism

Libertarians consider that there is an extended domain of individual freedom defined by every individual's person and private property, and that no one, whether private citizen or government, may may violate this boundary unless if necessary to repel an initiation of force or coercion. Indeed, libertarians consider that no organization, including government, can have any right except those that are voluntarily delegated to it by its members -- which implies that these members must have had these rights to delegate them to begin with. Libertarians apply this philosophy to civil as well as economic matters.

According to libertarians, decisions regarding how individuals should spend or invest their money should not be affected by a centralized governmental authority, hence their support of capitalism and opposition to statism. Thus, according to libertarians, taxation and regulation are at best necessary evils (as they involve coercion), and where unnecessary are simply evil. They believe government spending and regulations should be reduced whenever possible, in favor of allowing individuals autonomy in regard to how they spend their money. To many libertarians, governments should not establish schools, run hospitals, regulate industry, commerce or agriculture, or run social welfare programs. However, as almost all libertarians assert that children should have some special protections and not be treated as adults, it is not uncommon for some to make an exception for things such as public schools on grounds of efficiency, fairness, or both, though most would prefer a school voucher sytem to the status quo. For libertarians, government's main imperative should be Laissez-faire -- "Allow to do" -- a doctrine that opposes governmental interference in individual freedom and action, including opposing interference in economic affairs beyond the minimum necessary for the maintenance of peace and property rights.

Minarchist libertarians believe that minimizing the amount of money citizens pay to government, results in minimizing the possibility of citizens being a position to require financial assistance from government.

Libertarianism's Resurgence

In the 1980's, libertarianism grew substantially more popular and gained considerable influence in Republican administrations, though at the national level, the Libertarian party still fared poorly. However, in the 2000's, libertarian ideas are apparently influential on other political parties; for example, as of late, some Republicans are seriously proposing eliminating the IRS and income tax. Also, the "privatization" of Social Security is a popular topic of debate.

- Many trade barriers have been lifted, reducing what most libertarians argue are unneeded interferences with functioning markets and the right to use one's property as one sees fit.

- Ronald Reagan popularized anti-statism in the United States and passed some reforms

- In the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, Margaret Thatcher had much the same effect.

- Milton Friedman and Alan Greenspan have exerted considerable influence over monetary policy in favor of libertarian goals.

- Some victimless crimes such as sodomy have been decriminalized in the United States (see Lawrence v. Texas)

- Some states and local governments have relaxed laws on marijuana use and medical marijuana, though libertarians argue that the War on Drugs still constitutes one of the greatest threats to liberty in the United States as a whole.

- There are many (self-described) libertarian celebrities and libertarian figures in politics and the media

- Objectivism's popularity has greatly enhanced interest in libertarian ideas

Disputes Among Libertarians

Anarchists and Minarchists

All libertarians agree that government should be limited to what is strictly necessary, no more, no less. But there is no consensus among them about how much government is necessary. Hence, libertarians are further divided between the minarchists and the anarcho-capitalists, which are discussed at length in specific articles. Both minarchists and anarcho-capitalists differ in their beliefs from the anarcho-syndicalists, anarcho-socialists and libertarian socialists.

The minarchists believe that a "minimal" or a "night-watchman" state is necessary to guarantee property rights, economic and civil liberties, and that the proper function of government is limited to that purpose. For them, the legitimate functions of government might include the maintenance of the courts, the police, the military, and perhaps a few other vital functions (e.g., roads). Objectivism supports a form of minarchy that rejects all forms of state power outside of the police, courts, and military, but is willing to compromise in the short term through reforms such as privatization and vouchers.

The anarcho-capitalists, believe that even in matters of justice and protection and particularly in such matters, action by competing private responsible individuals (freely organized in businesses, cooperatives, or organizations of their choice) is preferable to government serving in these functions. While they consider themselves to be anarchists, they insist in rejecting any connotations attached to this term regarding support of a socialist ideal.

Minarchists consider anarcho-capitalists to be unrealistic to believe that governments can be wholly done without. Anarcho-capitalists consider that they are realists, and that minarchists are deluded to believe that a state monopoly of violence can be contained within any reasonable limits. Liberal and conservative critics of both these positions generally point to the historical record of democratic governments as evidence that democracy and popular rule have succeeded not only in containing government abuse of freedom, but have in fact transformed the state from a violent master of the people into their loyal and peaceful servant, at least in certain areas.

The minarchist/anarcho-capitalist division is friendly, and not generally a source of deep enmity, despite the sometimes involved theoretical arguments. Most libertarians feel much more strongly about their common support for individual liberty, responsibility and property, than about their possible minarchist vs. anarcho-capitalist differences. Since both minarchists and anarcho-capitalists believe that existing governments are far too intrusive, the two factions seek change in almost exactly the same directions, at least in the short term.

Many libertarians don't take a position with regard to this division, and don't care about it. Indeed, many libertarians consider that governments exist and will exist in the foreseeable future, up to the end of their lives, so that their efforts are better spent fighting, containing and avoiding the action of governments than trying to figure out what life could or couldn't be like without them. In recent years libertarianism has attracted many "fellow travelers" (to borrow a phrase from the Communists) who care little about such theoretical issues and merely wish to reduce the size, corruption, and intrusiveness of government. One subset is the South Park Republicans.

Some libertarian philosophers argue that, properly understood, minarchism and anarcho-capitalism are not in contradiction. See Revisiting Anarchism and Government by Tibor R. Machan.

Consequentialism, natural law, and reason

Libertarians tend to take primarily either an axiomatic natural law point of view, or a Consequentialist point of view, in justifying their beliefs. Some of them (like Frederic Bastiat), claim a natural harmony between these two points of view (that both are different views of the same truth), and consider it irrelevant to try to establish one as truer.

For natural rights libertarians, such as Robert Nozick, Murray Rothbard, and Hans-Hermann Hoppe, protecting rights is an end in itself. Though she rejects the label "libertarian," Ayn Rand also falls into this camp.

Consequentialist libertarians favor protection of rights not because they consider rights to be sacred, but instead because, in their view, protecting rights produces a society which has good results, such as an increase in wealth, safety, happiness, and fairness. An exposition of consequentialist libertarianism appears in David Friedman's book The Machinery of Freedom, which includes a chapter describing an allegedly highly-libertarian culture that existed in Iceland around 800 AD.

An alternate justification for libertarian ideas (broadly speaking), predicated on the use of reason and the observance of a certain code of ethics (rather than pursuit of social ends) is contained within the philosophy of Objectivism established by Ayn Rand. It should be noted that although Objectivism and libertarianism overlap, Rand did not consider herself a libertarian, and despite their potential as allies, she detested them even more than her natural political enemies, and opposed justifying capitalism through consequentialist means.

Some libertarians do not attempt to justify their beliefs in any external sense; they support libertarianism because they desire the maximum degree of liberty possible within their own lives, and see libertarianism as the most effective political philosophy towards this end.

The Role of Objectivism

According to Reason editor Nick Gillespie in the magazine's March 2005 issue focusing on objectivism's influence, Ayn Rand is "one of the most important figures in the libertarian movement... A century after her birth and more than a decade after her death, Rand remains one of the best-selling and most widely influential figures in American thought and culture" in general and in libertarianism in particular. He notes that "Rand provided 'liberal capitalism with a moral foundation.' That's no small feat in a world that, even after the fall of Nazism, communism, and other collectivist ideologies, still looks with suspicion on economic self-interest." Still, he confesses that he is embarassed by his magazine's association with her ideas." In the same issue, Cathy Young says that "Libertarianism, the movement most closely connected to Rand’s ideas, is less an offspring than a rebel stepchild," rebelling against what Gillespie calls "cult-like" orthodoxy.

The hostility between libertarians and objectivists, whose political agendas are barely distinguishable, is mutual; Rand said of libertarians that "They are not defenders of capitalism. They’re a group of publicity seekers... Further, their leadership consists of men of every of persuasion, from religious conservatives to anarchists. Moreover, most of them are my enemies... I’ve read nothing by a Libertarian (when I read them, in the early years) that wasn’t my ideas badly mishandled—i.e., had the teeth pulled out of them—with no credit given."

The source of the dispute, according to Rand, is that libertarians would "like to have an amoral political program." Rand believed that the only consistent defense of capitalism could come from her philosophy, which. Rand conceded that the two groups advocate the same political program, but saw libertarianism as too shallow to be effective, and believed that libertarians "can do the most harm to capitalism, by making it disreputable" by robbing it of its moral foundation. Many libertarians, by contrast, see objectivists as dogmatic, and see objectivism as what Young calls "a way station on a journey to some wider outlook" that is less totalistic.

Other Controversies Among libertarians

Libertarians do not agree on every topic. Although they share a common tradition of thinkers from centuries past to contemporary times, no thinker is considered a common authority whose opinions are to be blindly accepted. Rather, they are generally considered a reference to compare one's opinions and arguments with.

These controversies are addressed in separate articles:

- Libertarian perspectives on intellectual property

- Libertarian perspectives on immigration

- Libertarian perspectives on abortion

- Libertarian perspectives on the death penalty

- Libertarian perspectives on natural resources

- Libertarian perspectives on interventionism

Criticism of Libertarianism

Some political philosophies hold that human rights are incompatible with capitalism, the reasons for which are varied.

Conservative state apologists often argue that the state is needed to maintain social order and morality. They may argue that excessive personal freedoms encourage dangerous and irresponsible behaviour. Libertarians feel that the state has no business being involved in the affairs of consenting adults who are not infringing upon the rights of others.

Many criticisms of libertarianism revolve around the notion of that the "freedom" upheld by libertarians is a valid interpretation of the ideal. For example, liberals and socialists sometimes argue that the economic practices defended by libertarians result in privileges for a wealthy elite and violations of workers' rights.

See also

- See also: liberalism; minarchism; anarcho-capitalism; Austrian school; capitalism; Chicago school; Objectivism; individualist anarchism; libertarian communism; small-l libertarianism; The Free State Project; seasteading; Libertarian theories of law; deregulation; Republican Liberty Caucus, Mass surveillance, Libertarianism (philosophy), Positive liberty, Negative liberty, Paleolibertarianism, Lintarianism

- Opposes: mercantilism; statism; conservatism; collectivism; socialism; fabianism; communism; nazism; fascism; Welfare state; planned economy; state interventionism; regulation.

- Related topics: Civil Society; open society; political models; ideology; Liberator Online

- Libertarian blogs (On the Libertarian Wiki):

External links

Libertarian political parties

in the United States

- United States Libertarian Party

- Personal Choice Party

- Freedom Party USA

- Independence Party of Minnesota

outside the United States

- Australian Libertarian Party (The LDP)

- Australian Libertarian Web Site

- Libertarian Party of Bangladesh

- The Libertarian Society of Iceland

- Costa Rican Movimiento Libertario

- ACT the "Liberal Party" of New Zealand

- Libertarian Party of Canada

Libertarian think tanks

- Cato Institute

- Libertarian Alliance British think factory

- Advocates for Self-Government

- the International Society for Individual Liberty - see their Animated Introduction to the Philosophy of Liberty

- American Liberty Foundation

- Foundation for Economic Education

- Institute for Humane Studies

- Future of Freedom Foundation

- Ludwig von Mises Institute (Austrian school economics)

- Adam Smith Institute

Other libertarian political projects

Libertarian publications and Websites

- List of Notable Libertarian Theorists and Authors

- Ideas For Liberty Wiki

- The Libertarian Learning Centre

- Libertarian.org

- Free-Market.Net

- Libertarian Alliance (UK)

- Laissez Faire Books

- Individual Self-Determination Manifesto (Spanish)

- Libertarianpunk.com

- Open Directory links

- Liberté, j’écris ton nom

- Beloved Freedom

- Understanding The Libertarian Philosophy

- Imagine Freedom - A polemic on applied Libertarianism

- Perfiles del siglo XXI (A Libertarian magazine in Spanish

- LewRockwell.com

- A response by David Friedman to "A Non-Libertarian FAQ" (see below)

- The Freeman

- Liberty (magazine)

- Freedom Communications, Inc.

- Reason]

Critiques of libertarianism

- Critiques Of Libertarianism (includes sub-sections presenting anti-libertarian arguments from different political standpoints, as well as more general arguments)

- Comparison of Libertarians and Anarchists (Humor)

- What's wrong with libertarianism

- Libertarianism Makes You Stupid

- Why is libertarianism wrong?