| Revision as of 07:51, 14 January 2023 editSanati01 (talk | contribs)37 edits →History: Corrected contentTags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit← Previous edit | Revision as of 11:24, 15 January 2023 edit undoStarkex (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users1,711 edits →Emigration: →Infobox: region.Tags: citing a blog or free web host Visual editNext edit → | ||

| Line 27: | Line 27: | ||

| | pop3 = 180,980 | | pop3 = 180,980 | ||

| | ref3 = {{Citation needed|date=January 2023}} | | ref3 = {{Citation needed|date=January 2023}} | ||

| | region11 = {{flag| |

| region11 = {{flag|Hong Kong}} | ||

| | pop11 = |

| pop11 = 20,000 | ||

| | ref11 = <ref>{{Cite web|title= |

| ref11 = <ref>{{Cite web|title=Sindhi Association Hong Kong|url=https://sindhishongkong.com|access-date=2023-01-15}}</ref> | ||

| | region10 = {{flag|Afghanistan}} (]) | | region10 = {{flag|Afghanistan}} (]) | ||

| | pop10 = 25,000 (2017) | | pop10 = 25,000 (2017) | ||

| | ref10 = <ref>{{Cite web|title=Opinion: Sindhi beyond the borders|url=http://www.afghanistantimes.af/opinion-sindhi-beyond-the-borders/|access-date=2021-07-28|website=Afghanistan Times|language=en-US}}</ref> | | ref10 = <ref>{{Cite web|title=Opinion: Sindhi beyond the borders|url=http://www.afghanistantimes.af/opinion-sindhi-beyond-the-borders/|access-date=2021-07-28|website=Afghanistan Times|language=en-US}}</ref> | ||

| | region12 = {{flag| |

| region12 = {{flag|Bangladesh}} | ||

| | pop12 = |

| pop12 = 15,000 | ||

| | ref12 = <ref>{{Cite web|title=Opinion: Sindhi beyond the borders|url=http://www.afghanistantimes.af/opinion-sindhi-beyond-the-borders/|access-date=2021-07-28|website=Afghanistan Times|language=en-US}}</ref> | |||

| ⚫ | | |

||

| ⚫ | | region13 = {{flag|Canada}} | ||

| ⚫ | | |

||

| | pop13 = |

| pop13 = 12,065 | ||

| ⚫ | | ref13 = <ref>{{cite web | url=https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/prof/details/page.cfm?Lang=E&Geo1=PR&Code1=01&Geo2=PR&Code2=01&Data=Count&SearchText=01&SearchType=Begins&SearchPR=01&B1=All&Custom=&TABID=3 |title=Census Profile, 2016 Census – Canada and Canada | date=8 February 2017 }}</ref> | ||

| ⚫ | | |

||

| ⚫ | | region14 = {{flag|Singapore}}<ref name="encyclopedia_sindhis">{{cite web |title=Sindhis |url=https://www.encyclopedia.com/humanities/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/sindhis |website=Encyclopedia.com |publisher=Encyclopedia.com |access-date=10 June 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210507065744/https://www.encyclopedia.com/humanities/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/sindhis |archive-date=7 May 2021}}</ref> | ||

| ⚫ | | |

||

| | pop14 = 11,860 | |||

| ⚫ | | |

||

| ⚫ | | ref14 = <ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=39lJz_L4MdUC|title=Rising India and Indian Communities in East Asia|first1=K.|last1=Kesavapany|first2=A.|last2=Mani|first3=P. |last3=Ramasamy |date=2008|publisher=Institute of Southeast Asian Studies|isbn=9789812307996}}</ref> | ||

| | region15 = {{flag|Gibraltar}} | |||

| ⚫ | | pop15 = 500<ref>{{cite web|title=About, The Hindu community of Gibraltar|url=https://www.hinducommunity.gi/about}}</ref> | ||

| | languages = ]<br />{{smaller|], ] (]/] as ]) and numerous other languages widely spoken within the ]}} | | languages = ]<br />{{smaller|], ] (]/] as ]) and numerous other languages widely spoken within the ]}} | ||

| | rels = '''Majority''':<br />] ]: 80{{nbsp}}% <br /> | | rels = '''Majority''':<br />] ]: 80{{nbsp}}% <br /> | ||

| Line 153: | Line 156: | ||

| {{Main|Sindhi diaspora}}The Sindhi ] is significant. ] from the ] existed before however it became ] after the 19th century with the ] a notable example was when Sindhi ] emigrated to ]<ref>{{Cite web |last=Kamalakaran |first=Ajay |title=In the story of Sindhi migration, Canary Islands played a small but important role |url=https://scroll.in/magazine/1033151/in-the-story-of-sindhi-migration-canary-islands-played-a-small-but-important-role |access-date=2023-01-13 |website=Scroll.in |language=en-US}}</ref> to the point of reaching ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Peck |first=James |title=Hindus on a rock |work=The Sindhis of Gibraltar derive their traditions from being part of the global Sindhi sect that originates from the Sindh region of Pakistan. Theologically associated with Hinduism and Sikhism, Sindhis held many important jobs before and during British colonial rule of the Sindh region especially as merchants trading across the British Empire. |publisher=Oxford Brookes University |year=2004 |location=United Kingdom |pages=1}}</ref> | {{Main|Sindhi diaspora}}The Sindhi ] is significant. ] from the ] existed before however it became ] after the 19th century with the ] a notable example was when Sindhi ] emigrated to ]<ref>{{Cite web |last=Kamalakaran |first=Ajay |title=In the story of Sindhi migration, Canary Islands played a small but important role |url=https://scroll.in/magazine/1033151/in-the-story-of-sindhi-migration-canary-islands-played-a-small-but-important-role |access-date=2023-01-13 |website=Scroll.in |language=en-US}}</ref> to the point of reaching ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Peck |first=James |title=Hindus on a rock |work=The Sindhis of Gibraltar derive their traditions from being part of the global Sindhi sect that originates from the Sindh region of Pakistan. Theologically associated with Hinduism and Sikhism, Sindhis held many important jobs before and during British colonial rule of the Sindh region especially as merchants trading across the British Empire. |publisher=Oxford Brookes University |year=2004 |location=United Kingdom |pages=1}}</ref> | ||

| After the ], Sindhis (More notably ]) started ] with many Sindhis settling in ] especially in ],<ref>{{Cite book |last=David |first=Maya Khemlani |title=The Sindhi Hindus of London |publisher=University of Malaya |year=2001 |location=Malaysia}}</ref> ] as well as ] such as the ] and ].{{Citation needed|date=January 2023}} | After the ], Sindhis (More notably ]) started ] with many Sindhis settling in ] especially in ],<ref>{{Cite book |last=David |first=Maya Khemlani |title=The Sindhi Hindus of London |publisher=University of Malaya |year=2001 |location=Malaysia}}</ref> ] as well as ] such as the ] and ].{{Citation needed|date=January 2023}}, Some are settled in rich countries like ]<ref>{{Cite web |date=2019-08-15 |title=They made a life in Hong Kong: Hindus on India’s partition |url=https://www.scmp.com/lifestyle/family-relationships/article/3022689/hindus-sindh-who-fled-india-hong-kong-partition |access-date=2023-01-15 |website=South China Morning Post |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Homepage of Sindhi Association of Hongkong & China |url=http://sindhishongkong.com/home |access-date=2023-01-15 |website=sindhishongkong.com}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last=Roshni |title=Hong Kong Sindhis: Living in a Bubble! |url=http://roshniwritenow.blogspot.com/2010/10/hong-kong-sindhis-living-in-bubble.html |access-date=2023-01-15 |website=Roshni Write Now}}</ref> and ]. | ||

| ]</ref> 1845]] | ]</ref> 1845]] | ||

Revision as of 11:24, 15 January 2023

Ethnolinguistic group native to Sindh"Sindhi people" redirects here. Not to be confused with the Sinti people.. Ethnic group

Sindhi women in traditional Sindhi dress in Sindh, Pakistan Sindhi women in traditional Sindhi dress in Sindh, Pakistan | |

| Total population | |

| c. 47 million (est.) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 34,252,262 | |

| 3,810,000 | |

| 180,980 | |

| 94,620 | |

| 51,015 | |

| 38,760 | |

| 25,000 (2017) | |

| 20,000 | |

| 15,000 | |

| 12,065 | |

| 11,860 | |

| 500 | |

| Languages | |

| Sindhi English, Hindi–Urdu (Sanskrit/Arabic as liturgical languages) and numerous other languages widely spoken within the Sindhi diaspora | |

| Religion | |

| Majority: Minority:

| |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Indo-Aryan peoples | |

Sindhis (Template:Lang-sd (Perso-Arabic); सिन्धी (Devanagari); /ˈsɪndis/ romanised as sin-dheē) are an Indo-Aryan ethnic group who speak the Sindhi language and are native to the Sindh region in Pakistan. Historically concentrated around the center of Indus River, Sindhi people have been native to Sindh throughout history, apart from that their historical region has always came from the South-eastern side of Balochistan, the Bahawalpur region of Punjab and the Kutch region of Gujarat, India. Having been isolated throughout history unlike its neighbors, Sindhi culture has preserved its own uniqueness.

After the partition of British Indian empire in 1947, many Sindhi Hindus and Sindhi Sikhs migrated to the newly independent Dominion of India and other parts of the world. Pakistani Sindhis are predominantly Muslim with a smaller Sikh and Hindu minority, whereas Indian Sindhis are predominantly Hindu with a Sikh, Jain and Muslim minority that refused to go to Pakistan. The Sindhi diaspora is growing around the world, especially in the Middle East, owing to better employment opportunities. Despite being geographically separated from each other members Sindhis still maintain strong ties back home sharing same cultural values practices keeping alive unique heritage passed down generations through centuries preserving its rich history legacy.

| Part of a series on |

| Sindhis |

|---|

|

| Identity |

| History |

|

DiasporaAsia

Europe North America Oceania |

| Culture |

| Regions |

Sindh portal |

Etymology

The name Sindhi is derived from the Sanskrit Sindhu which translates as river or seabody, the original name of the Indus River and the surrounding region, which is where Sindhi is spoken. 20th century Western scholars such as George Abraham Grierson believed that Sindhi descended specifically from the Vrācaḍa dialect of Apabhramsha.

Geographic Distribution

Sindh has been a ethnic historical region in Northwestern India, unlike is neighbors Sindh did not experience violent invasions, Boundaries of various Kingdoms and rules in Sindh were defined on ethnic lines. Throughout history the geographical definition for Sindh referred to the south of Indus and its neighboring regions.

Pakistan

In Pakistan as per 2017 census, Sindhis are the 3rd largest ethnic group below Pashtuns and followed by Saraikis, Sindhis account for 14% of Pakistan's population with estimated 34,250,000 people.

Sufism has been an important aspect in the spiritual life of Muslim Sindhis as a result Sufism has become a marker of identity in Sindh. Sindhis in Pakistan have province for them, Sindh, It also has the largest population of Hindus in Pakistan with 93% of Hindus in Sindh and rest are in other provinces.

India

In India as per 2011 census, Sindhis have an estimated population of mere 2,770,000 million unlike Sindhis in Pakistan, Indian Sindhis do not have a define state for them hence they are scattered throughout India in states like Gujarat, Maharashtra and Rajasthan.

Diaspora

See also: Sindhi diasporaHistory

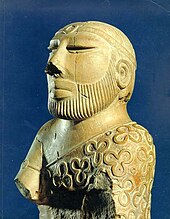

See also: History of SindhSindh was the site of one of the Cradle of civilizations, the bronze age Indus Valley civilisation that flourished from about 3000 B.C. The Indo-Aryan tribes of Sindh gave rise to the Iron age vedic civilization, which lasted till 500 BC. During this era, the Vedas were composed. In 518 BC, the Achaemenid empire conquered Indus valley and established Hindush satrapy in Sindh. Following Alexander the Great's invasion, Sindh became part of the Mauryan Empire. After its decline, Indo-Greeks, Indo-Scythians and Indo-Parthians ruled in Sindh.

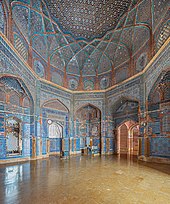

Sindh is sometimes referred to as the Bab-ul Islam (transl. 'Gateway of Islam'), as it was one of the first regions of the Indian subcontinent to fall under Islamic rule. Parts of the modern-day province were intermittently subject to raids by the Rashidun army during the early Muslim conquests, but the region did not fall under Muslim rule until the Arab invasion of Sind occurred under the Umayyad Caliphate, headed by Muhammad ibn Qasim in 712 CE. Afterwards, Sindh was ruled by a series of dynasties including Habbaris, Soomras, Sammas, Arghuns and Tarkhans. The Mughal empire conquered Sindh in 1591 and organized it as Subah of Thatta, the first-level imperial division. Sindh again became independent under Kalhora dynasty. The British conquered Sindh in 1843 AD after Battle of Hyderabad from the Talpur dynasty. Sindh became separate province in 1936, and after independence became part of Pakistan.

Pre-historic period

Sindh and surrounding areas contain the ruins of the Indus Valley Civilization. There are remnants of thousand-year-old cities and structures, with a notable example in Sindh being that of Mohenjo Daro. Built around 2500 BCE, it was one of the largest settlements of the ancient Indus civilisation or Harappan culture, with features such as standardized bricks, street grids, and covered sewerage systems. It was one of the world's earliest major cities, contemporaneous with the civilizations of ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, Minoan Crete, and Caral-Supe. Mohenjo-daro was abandoned in the 19th century BCE as the Indus Valley Civilization declined, and the site was not rediscovered until the 1920s. Significant excavation has since been conducted at the site of the city, which was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1980. The site is currently threatened by erosion and improper restoration.

The cities of the ancient Indus were noted for their urban planning, baked brick houses, elaborate drainage systems, water supply systems, clusters of large non-residential buildings, and techniques of handicraft and metallurgy. Mohenjo-daro and Harappa very likely grew to contain between 30,000 and 60,000 individuals, and the civilisation may have contained between one and five million individuals during its florescence. A gradual drying of the region during the 3rd millennium BCE may have been the initial stimulus for its urbanisation. Eventually it also reduced the water supply enough to cause the civilisation's demise and to disperse its population to the east.

Historical period

For several centuries in the first millennium B.C. and in the first five centuries of the first millennium A.D., western portions of Sindh, the regions on the western flank of the Indus river, were intermittently under Persian, Greek and Kushan rule, first during the Achaemenid dynasty (500–300 BC) during which it made up part of the easternmost satrapies, then, by Alexander the Great, followed by the Indo-Greeks and still later under the Indo-Sassanids, as well as Kushans, before the Islamic conquest between the 7th–10th century AD. Alexander the Great marched through Punjab and Sindh, down the Indus river, after his conquest of the Persian Empire.

The Ror dynasty was a power from the Indian subcontinent that ruled modern-day Sindh and Northwest India from 450 BC – 489 AD.

Medieval period

Sindh was one of the earliest regions to be conquered by the Arabs and influenced by Islam after 720 AD. Before this period, it was heavily Hindu and Buddhist. After 632 AD, it was part of the Islamic empires of the Abbasids and Umayyids. Habbari, Soomra, Samma, Kalhora dynasties ruled Sindh.

Baloch migrations in the region between 14th–18th centuries and many Baloch dynasties saw a high Iranic mixture into Sindhis.

Modern period

British Rule

The British conquered Sindh in 1843. General Charles Napier is said to have reported victory to the Governor General with a one-word telegram, namely "Peccavi" – or "I have sinned" (Latin), which was later turned into a pun known as "Forgive me for i have Sindh".

The British had two objectives in their rule of Sindh: the consolidation of British rule and the use of Sindh as a market for British products and a source of revenue and raw materials. With the appropriate infrastructure in place, the British hoped to utilise Sindh for its economic potential.

The British incorporated Sindh, some years later after annexing it, into the Bombay Presidency. The distance from the provincial capital, Bombay, led to grievances that Sindh was neglected in contrast to other parts of the Presidency. The merger of Sindh into Punjab province was considered from time to time but was turned down because of British disagreement and Sindhi opposition, both from Muslims and Hindus, to being annexed to Punjab.

Post-colonial era

In 1947, violence did not constitute a major part of the Sindhi partition experience, unlike in Punjab. There were very few incidents of violence on Sindh, in part due to the Sufi-influenced culture of religious tolerance and in part that Sindh was not divided and was instead made part of Pakistan in its entirety. Sindhi Hindus who left generally did so out of a fear of persecution, rather than persecution itself, because of the arrival of Muslim refugees from India. Sindhi Hindus differentiated between the local Sindhi Muslims and the migrant Muslims from India. A large number of Sindhi Hindus travelled to India by sea, to the ports of Bombay, Porbandar, Veraval and Okha.

Demographics

Ethnicity and religion

Main article: Demographics of Sindh

The two main tribes of Sindh are the Soomro — descendants of the Soomro Dynasty, who ruled Sindh during 970–1351 A.D. — and the Samma — descendants of the Samma Dynasty, who ruled Sindh during 1351–1521 A.D. These tribes belong to the same bloodline. Among other Sindhi Rajputs are the Bhuttos, Kambohs, Bhattis, Bhanbhros, Mahendros, Buriros, Bhachos, Chohans, Lakha, Sahetas, Lohanas, Mohano, Dahars, Indhar, Chhachhar/Chachar, Dhareja, Rathores, Dakhan, Langah, Junejo, Mahars etc. One of the oldest Sindhi tribe is the Charan. The Sindhi-Sipahi of Rajasthan and the Sandhai Muslims of Gujarat are communities of Sindhi Rajputs settled in India. Closely related to the Sindhi Rajputs are the Jats of Sindh, who are found mainly in the Indus delta region. However, tribes are of little importance in Sindh as compared to in Punjab and Balochistan. Identity in Sindh is mostly based on a common ethnicity.

Sindhi Hindus

Main articles: Sindhi Hindus, Hinduism in Sindh Province, and Sindhis in IndiaHinduism along with Buddhism was the predominant religion in Sindh before the Arab Islamic conquest. The Chinese Buddhist monk Xuanzang, who visited the region in the years 630–644, said that Buddhism dominated, but also noted that it was declining. While Buddhism declined and ultimately disappeared after Arab conquest mainly due to conversion of almost entire Buddhist population to Islam, Hinduism managed to survive through the Muslim rule until before the partition of India as a significant minority. Derryl Maclean explains what he calls "the persistence of Hinduism" on the basis of "the radical dissimilarity between the socio-economic bases of Hinduism and Buddhism in Sind" : Buddhism in this region was mainly urban and mercantile while Hinduism was rural and non-mercantile, thus the Arabs, themselves urban and mercantile, attracted and converted the Buddhist classes, but for the rural and non-mercantile parts, only interested by the taxes, they promoted a more decentralized authority and appointed Brahmins for the task, who often just continued the roles they had in the previous Hindu rule.

According to the 1998 census of Pakistan, Hindus constituted about 8% of the total population of Sindh province. Most of them live in urban areas such as Karachi, Hyderabad, Sukkur and Mirpur Khas. Hyderabad is the largest centre of Sindhi Hindus in Pakistan, with 100,000–150,000 living there. The ratio of Hindus was higher before the independence of Pakistan in 1947.

Before 1947 however, other than a few Gujarati speaking Parsees (Zorastrians) living in Karachi, virtually all the inhabitants were Sindhis, whether Muslim or Hindu at the time of Pakistan's independence, 75% of the population were Muslims and almost all the remaining 25% were Hindus.

Hindus in Sindh were concentrated in the urban areas before the Partition of India in 1947, during which most migrated to modern-day India according to Ahmad Hassan Dani. In the urban centres of Sindh, Hindus formed the majority of the population before the partition. According to the 1941 Census of India, Hindus formed around 74% of the population of Hyderabad, 70% of Sukkur, 65% of Shikarpur and about half of Karachi. By the 1951 census, all of these cities had virtually been emptied of their Hindu population as a result of the partition.

The Cities and towns of Sindh were dominated by the Hindus. In 1941, for example, Hindus were 64% of the total urban population.

Hindus were also spread over the rural areas of Sindh province. Thari (a dialect of Sindhi) is spoken in Sindh in Pakistan and Rajasthan in India.

Sindhi Muslims

The connection between the Indus Valley and Islam was established by the initial Muslim missions. According to Derryl N. Maclean, a link between Sindh and Muslims during the Caliphate of Ali can be traced to Hakim ibn Jabalah al-Abdi, a companion of the Islamic Prophet Muhammad, who traveled across Sind to Makran in the year 649AD and presented a report on the area to the Caliph. He supported Ali, and died in the Battle of the Camel alongside Sindhi Jats. He was also a poet and few couplets of his poem in praise of Ali ibn Abu Talib have survived, as reported in Chachnama:

Template:Lang-ar "Oh Ali, owing to your alliance (with the prophet) you are true of high birth, and your example is great, and you are wise and excellent, and your advent has made your age an age of generosity and kindness and brotherly love".

During the reign of Ali, many Jats came under the influence of Islam. Harith ibn Murrah Al-abdi and Sayfi ibn Fil' al-Shaybani, both officers of Ali's army, attacked Sindhi bandits and chased them to Al-Qiqan (present-day Quetta) in the year 658. Sayfi was one of the seven partisans of Ali who were beheaded alongside Hujr ibn Adi al-Kindi in 660AD, near Damascus.

In 712 A.D., Sindh was incorporated into the Caliphate, the Islamic Empire, and became the "Arabian gateway" into India (later to become known as Bab-ul-Islam, the gate of Islam).

Sindh produced many Muslim scholars early on, "men whose influence extended to Iraq where the people thought highly of their learning", in particular in hadith, with the likes of poet Abu al- 'Ata Sindhi (d. 159) or hadith and fiqh scholar Abu Mashar Sindhi (d. 160), among many others, and they're also those who translated scientific texts from Sanskrit into Arabic, for instance, the Zij al-Sindhind in astronomy.

The majority of Muslim Sindhis follow the Sunni Hanafi fiqh with a minority being Shia Ithna 'ashariyah. Sufism has left a deep impact on Sindhi Muslims and this is visible through the numerous Sufi shrines which dot the landscape of Sindh.

Sindhi Muslim culture is highly influenced by Sufi doctrines and principles. Some of the popular cultural icons are Shah Abdul Latif Bhitai, Lal Shahbaz Qalandar, Jhulelal and Sachal Sarmast.

Tribes

Main article: List of Sindhi tribesMajor tribes in Sindh include Soomros, Sammas, Kalhoras, Bhuttos and Rajper, all of these tribes have significant influence in Sindh.

Emigration

Main article: Sindhi diasporaThe Sindhi diaspora is significant. Emigration from the Sindh existed before however it became mainstream after the 19th century with the conquest of Sindh a notable example was when Sindhi traders emigrated to Canary Islands to the point of reaching Gibraltar.

After the partition, Sindhis (More notably Hindus) started emigrated with many Sindhis settling in Europe especially in UK, North America as well as Middle Eastern states such as the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia., Some are settled in rich countries like Hong Kong and Singapore.

Culture

Main article: Sindhi cultureSindhi culture has its roots in the Indus Valley civilization. Sindh has been shaped by the largely desert region, the natural resources it had available, and continuous foreign influence. The Indus or Sindhu River that passes through the land, and the Arabian Sea (that defines its borders) also supported the seafaring traditions among the local people. The local climate also reflects why the Sindhis have the language, folklore, traditions, customs and lifestyle that are so different from the neighboring regions. The Sindhi culture is also practiced by the Sindhi diaspora.

The roots of Sindhi culture go back to the distant past. Archaeological research during 19th and 20th centuries showed the roots of social life, religion and culture of the people of the Sindh: their agricultural practices, traditional arts and crafts, customs and tradition and other parts of social life, going back to a mature Indus Valley Civilization of the third millennium BC. Recent researches have traced the Indus valley civilization to even earlier ancestry.

Traditional dress

See also: Sindhi clothingThe traditional Sindhi dress varies from tribe to tribe but most common are Lehenga Choli and Shalwar Cholo with sindhi embroideries and mirror work for women and long veil is important, traditional dress for men is the Sindhi version of Shalwar Qameez/Kurta and Ajrak/Lungi(shawls) with either sindhi Patka or sindhi topi.

Literature

See also: Sindhi literatureSindhi language is ancient and rich in literature. Its writers have contributed extensively in various forms of literature in both poetry and prose. Sindhi literature is very rich, and is one of the world's oldest literatures. The earliest reference to Sindhi literature is contained in the writings of Arab historians. It is established that Sindhi was the first eastern language into which the Quran was translated, in the 8th or 9th century. There is evidence of Sindhi poets reciting their verses before the Muslim Caliphs in Baghdad. It is also recorded that treatises were written in Sindhi on astronomy, medicine and history during the 8th and 9th centuries.

Sindhi literature, is the composition of oral and written scripts and texts in the Sindhi language in the form of prose: (romantic tales, and epic stores) and poetry: (Ghazal, Wai and Nazm). The Sindhi language is considered to be the one of the oldest languages of Ancient India, due to the influence on the language of Indus Valley inhabitants. Sindhi literature has developed over a thousand years.

According to the historians, Nabi Bux Baloch, Rasool Bux Palijo, and GM Syed, Sindhi had a great influence on the Hindi language in pre-Islamic times. Nevertheless, after the advent of Islam in eighth century, Arabic language and Persian language influenced the inhabitants of the area and were the official language of territory through different periods.

Music

See also: Sindhi musicMusic from Sindh, is sung and is generally of 5 genres that orignated in Sindh, The First one is the "Baits". The Baits style is vocal music in Sanhoon (low voice) or Graham (high voice). Second "Waee" instrumental music is performed in a variety of ways using a string instrument. Waee, also known as Kafi, other genres are Lada/Sehra/Geech, Dhammal, Doheera. The sindhi folk musical instruments are Algozo, Tamburo, Chung, Yaktaro, Dholak, Khartal/Chapri/Dando, Sarangi, Surando, Benjo, Bansri, Borindo, Murli/Been, Gharo/Dilo, Tabla, Khamach/khamachi, Narr, Kanjhyun/Talyoon, Duhl Sharnai and Muto, Nagaro, Danburo, Ravanahatha.

Dance

See also: Folk dances of SindhDances of Sindh include the famous Ho-Jamalo and Dhammal,. Common dances include Jhumar/Jhumir (Different from Jhumar dance of South Punjab), Kafelo, Jhamelo however none of these have survived as much as Ho-Jamalo. In marriages and on other occasions, a special type of song is produced these are known as Ladas/Sehra/Geech and these are sung to celebrate the occasion of marriage, birth and on other special days, these are mostly performed by women.

Some popular dances include:

- Jamalo: The notable Sindhi dance which is celebrated by Sindhis across the world.

- Jhumar/Jhumir: Performed on weddings and on special occasions.

- Dhamaal: is a mystical dance performed by Dervish.

- Chej, Although Chej has seen decline in Sindh but it remains popular among Sindhi Hindus and diaspora.

- Bhagat: is a dance performed by professionals to entertain visiting people.

- Doka/Dandio: Dance performed using sticks.

- Charuri: Performed in thar.

- Muhana Dance: A dance performed by fishermen and fisherwomen of Sindh.

- Rasudo: Dance of nangarparker.

Folk tales

See also: Sindhi folkloreSindhi folklore are folk traditions which have developed in Sindh over a number of centuries. Sindh abounds with folklore, in all forms, and colors from such obvious manifestations as the traditional Watayo Faqir tales, the legend of Moriro, epic tale of Dodo Chanesar, to the heroic character of Marui which distinguishes it among the contemporary folklores of the region. The love story of Sassui, who pines for her lover Punhu, is known and sung in every Sindhi settlement. examples of the folklore of Sindh include the stories of Umar Marui and Suhuni Mehar. Sindhi folk singers and women play a vital role to transmit the Sindhi folklore. They sang the folktales of Sindh in songs with passion in every village of Sindh. Sindhi folklore has been compiled in a series of forty volumes under Sindhi Adabi Board's project of folklore and literature. This valuable project was accomplished by noted Sindhi scholar Nabi Bux Khan Baloch. folk tales like Dodo Chanesar, Sassi Punnu, Moomal Rano, and Umar Marvi are examples of Sindhi folk-talkes

The most famous Sindhi folk tales are known as the Seven Heroines of Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai, some notable tales include:

Festivals

See also: Sindhi Festivals and Sindhi Cultural DaySindhis are very festive and like to organize festivals to commemorate their culture and heritage, most Sindhi celebrate the Sindhi Culture day which is celebrated regardless of religion to express their love for their culture. It is observed with a great zeal.

Muslim

Sindhi Muslims celebrate Islamic festivals such as Eid-ul-Adha and Eid al-Fitr which are celebrated with zeal and enthusiasm. A festival known as Jashn-e-Larkana is also celebrated by Sindhi muslims.

Hindu

Compared to their Muslim counterparts, Hindu festivals are numerous and largely dependent on respective caste many Hindus have festivals based on a certain deity, common festivals include Cheti Chand (Sindhi new-year) Teejri, Thadri, Utraan.

Cuisine

| It has been suggested that Sindhi cuisine be merged into this section. (Discuss) Proposed since October 2022. |

Sindhi cuisine has been influenced by Central Asian, Iranian, Mughal food traditions. It is mostly a non-vegetarian cuisine, with even Sindhi Hindus widely accepting of meat consumption. The daily food in most Sindhi households consists of wheat-based flat-bread (phulka) and rice accompanied by two dishes, one gravy and one dry with curd, papad or pickle. Freshwater fish and a wide variety of vegetables are usually used in Sindhi cuisine.

Restaurants specializing in Sindhi cuisine are rare, although it is found at truck stops in rural areas of Sindh province, and in a few restaurants in urban Sindh.

The arrival of Islam within India influenced the local cuisine to a great degree. Since Muslims are forbidden to eat pork or consume alcohol and the Halal dietary guidelines are strictly observed, Muslim Sindhis focus on ingredients such as beef, lamb, chicken, fish, vegetables and traditional fruit and dairy. Hindu Sindhi cuisine is almost identical with the difference that beef is omitted. The influence of Central Asian, South Asian and Middle Eastern cuisine in Sindhi food is ubiquitous. Sindhi cuisine was also found in India, where many Sindhi Hindus migrated following the Partition of India in 1947. Before Independence, the State of Sindh was under Bombay Presidency.

Culture Day

This section is an excerpt from Sindhi Cultural Day.Sindhi Cultural Day (Sindhi: سنڌي ثقافتي ڏھاڙو) is a popular Sindhi cultural festival. It is celebrated with traditional enthusiasm to highlight the centuries-old rich culture of Sindh. The day is celebrated each year in the first week of December on the Sunday. It's widely celebrated all over Sindh, and amongst the Sindhi diaspora population around the world. Sindhis celebrate this day to demonstrate the peaceful identity of Sindhi culture and acquire the attention of the world towards their rich heritage.

Sindhi cultural day is celebrated worldwide on the first Sunday of December. On this occasion, people wear attires, Ajrak (traditional block printed shawl) and Sindhi Topi. During the festival, people gather in all major cities of Sindh at press clubs, and other places to arrange various activities. Literary (poetic) gatherings, mach katchehri (gathering in a place and sitting round in a circle and the fire on sticks in the center), musical concerts, seminars, lecture programs and rallies are held. Major hallmarks of cities and towns are decorated with Sindhi Ajrak. People across Sindh exchange gifts of Ajrak and Topi at various ceremonies. The children and women dress up in Ajrak, assembling at the grand gathering, where famous Sindhi singers sing Sindhi songs, which depicts the message of Sindh peace and love. The musical performances of the artists compel the participants to dance to Sindhi tunes and the national song, sung by Ahmed Mughal (Brother of Late Rehman Mughal) ‘Hea Sindh Jeay-Sindh Wara Jean Sindhi Topi Ajrak Wara Jean’.

All political, social and religious organizations of Sindh, besides the Sindh Culture Department and administrations of various schools, colleges and universities, organize a variety of events including seminars, debates, folk music programs, drama and theatric performances, tableaus and literary sittings to mark this annual festivity. On Sindhi culture day, history and heritage are highlighted at the events.

| Part of a series on |

| Sindhis |

|---|

|

| Identity |

| History |

|

DiasporaAsia

Europe North America Oceania |

| Culture |

| Regions |

Sindh portal |

Poetry

See also: Sindhi poetryProminent in Sindhi culture, continues an oral tradition dating back a thousand years. The verbal verses were based on folk tales. Sindhi is one of the major oldest languages of the Indus Valley having a peculiar literary colour both in poetry and prose. Sindhi poetry is very rich in thought as well as contain variety of genres like other developed languages. Poetry of Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai and Sachal Sarmast is very famous throughout Sindh.

Notable people

Main article: List of Sindhi people-

Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, ninth prime minister of Pakistan

Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, ninth prime minister of Pakistan

-

Abdul Majid Bhurgri, Sindhi computer scientist

Abdul Majid Bhurgri, Sindhi computer scientist

-

Fahad Mustafa, Sindhi actor in Lollywood

Fahad Mustafa, Sindhi actor in Lollywood

-

Shah Abdul Latif Bhitati, Sindhi Sufi saint of 18th century

Shah Abdul Latif Bhitati, Sindhi Sufi saint of 18th century

-

Abida Parveen, notable Sufi musician

Abida Parveen, notable Sufi musician

-

L. K. Advani, 7th deputy prime minister of India

L. K. Advani, 7th deputy prime minister of India

-

Tarun Tahiliani, notable Indian fashion designer

Tarun Tahiliani, notable Indian fashion designer

-

Benazir Bhutto, 11th and 13th prime minister of Pakistan

Benazir Bhutto, 11th and 13th prime minister of Pakistan

-

Gulu Lalvani, Indian Sindhi businessman

Gulu Lalvani, Indian Sindhi businessman

-

Imdad Ali, Sindhi philosopher and educationist

Imdad Ali, Sindhi philosopher and educationist

-

Sachal Sarmast, Sindhi legendary poet

Sachal Sarmast, Sindhi legendary poet

-

Shaikh Ayaz, Sindhi language poet

Shaikh Ayaz, Sindhi language poet

-

Kumail Nanjiani, American Sindhi comedian and actor

Kumail Nanjiani, American Sindhi comedian and actor

-

Sunil Vaswani, Indian billionaire businessman

Sunil Vaswani, Indian billionaire businessman

See also

- Cheti Chand

- Nanakpanthi

- Guru Nanak Jayanti

- Sindhudesh

- Sindhi nationalism

- Sindhis in India

- Sindhi Hindus

- Hinduism in Sindh Province

- Sindhi Sikhs

- Sandhai Muslims

- List of Sindhi people

- Ulhasnagar

- Sindhi names

- Sindhi Pathan

- Sindhi Baloch

- Sindhi bhagat

- Sindhi Memon

- Sammat

- Sandhai Muslims

- Sindhi language media in Pakistan

- Sindhi-language media

- List of Sindhi-language newspapers

- Sindhi Language Authority

- Sindhi Adabi Board

- Sindhi Adabi Sangat

- Sindhi folk tales

- Sindhi folklore

- Sindhi music

- List of Sindhi singers

- Sindhi music videos

- Sindhi poetry

- Tomb paintings of Sindh

- List of Sindhi singers

- List of Sindhi festivals

- Sindhi culture

- Sindhi biryani

- Sindhi Camp

- Sindhi cap

- Sindhi Cultural Day

- Sindhi cinema

- Sindhi colony

- Sindhi cuisine

- Sindhi High School, Hebbal

- Romanisation of Sindhi

Notes

- Includes people who speak the Sindhi and Kutchi languages. Ethnic Sindhis who no longer speak the language are not included in this number.

- These covered carnelian products, seal carving, work in copper, bronze, lead, and tin.

References

- "Pakistan". 17 August 2022.

- "Scheduled Languages in descending order of speaker's strength – 2011" (PDF). Registrar General and Census Commissioner of India. 29 June 2018.

- http://www.ophrd.gov.pk/SiteImage/Downloads/Year-Book-2017-18.pdf

- http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/census/2011-census/key-statistics-and-quick-statistics-for-local-authorities-in-the-united-kingdom---part-1/rft-ks201uk.xls

- "Explore Census Data". Archived from the original on 26 November 2020.

- "Opinion: Sindhi beyond the borders". Afghanistan Times. Retrieved 28 July 2021.

- "Sindhi Association Hong Kong". Retrieved 15 January 2023.

- "Opinion: Sindhi beyond the borders". Afghanistan Times. Retrieved 28 July 2021.

- "Census Profile, 2016 Census – Canada [Country] and Canada [Country]". 8 February 2017.

- "Sindhis". Encyclopedia.com. Encyclopedia.com. Archived from the original on 7 May 2021. Retrieved 10 June 2022.

- Kesavapany, K.; Mani, A.; Ramasamy, P. (2008). Rising India and Indian Communities in East Asia. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 9789812307996.

- "About, The Hindu community of Gibraltar".

- "Kashmiri: A language of India". Ethnologue. Retrieved 2 June 2007.

- ^ Butt, Rakhio (1998). Papers on Sindhi Language & Linguistics. ISBN 9789694050508. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- "Culture". www.wwf.org.pk. Retrieved 4 January 2023.

- ^ Ahmed, Ashfaq (7 December 2021). "Indian and Pakistani Sindhi expats together celebrate Sindhi Cultural Day with fanfare in Dubai". Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- David, Maya Khemlani; Abbasi, Muhammad Hassan Abbasi; Ali, Hina Muhammad (January 2022). Young Sindhi Muslims in Cultural Maintenance in the Face of Language Shift. ResearchGate.com.

Despite a shift away from habitual use of Sindhi language, they have maintained their cultural values and norms.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - Mahajan, V. D. (2007). History of Medieval India. S. Chand Publishing. ISBN 978-81-219-0364-6.

Sindh was isolated from the rest of India and consequently nobody took any interest in Sindh and the same was conquered by the Arabs.

- Hasnain, Khalid (19 May 2021). "Pakistan's population is 207.68m, shows 2017 census result". DAWN.COM. Retrieved 25 December 2022.

- Levesque, Julien (2016). "Sindhis are Sufi by Nature": Sufism as a Marker of Identity in Sindh. HAL Open Science. pp. 212–227. ISBN 9781138910683.

- Harjani, Dayal N. (19 July 2018). Sindhi Roots & Rituals - Part 1. Notion Press. ISBN 978-1-64249-289-7.

Sindhi folklore, literature, poetry, music came to be influenced by Sufi ideologies to a great extent and therefore Sindhi psyche has been ingrained with piousness and the veneration of saints and visits to Dargahs

- "Hindus under the official Muslims of Pakistan". Daily Times. 17 July 2020. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- Singh, Rajkumar (11 November 2019). "Religious profile of today's Pakistani Sindh Province". South Asia Journal. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- "2011 Census of India". 2011. Retrieved 25 December 2022.

- Sanyal, Sanjeev (10 July 2013). Land of the seven rivers : a brief history of India's geography. ISBN 978-0-14-342093-4. OCLC 855957425.

- "Mohenjo-Daro: An Ancient Indus Valley Metropolis".

- "Mohenjo Daro: Could this ancient city be lost forever?". BBC News. 26 June 2012. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- Wright 2009, pp. 115–125. sfn error: no target: CITEREFWright2009 (help)

- Dyson 2018, p. 29 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFDyson2018 (help) "Mohenjo-daro and Harappa may each have contained between 30,000 and 60,000 people (perhaps more in the former case). Water transport was crucial for the provisioning of these and other cities. That said, the vast majority of people lived in rural areas. At the height of the Indus valley civilization the subcontinent may have contained 4-6 million people."

- McIntosh 2008, p. 387: "The enormous potential of the greater Indus region offered scope for huge population increase; by the end of the Mature Harappan period, the Harappans are estimated to have numbered somewhere between 1 and 5 million, probably well below the region's carrying capacity." sfn error: no target: CITEREFMcIntosh2008 (help)

- Dayal, N. Harjani (19 July 2018). Sindhi Roots & Rituals – Part 1. Notion Press. ISBN 978-1-64249-289-7.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - J.C, Aggarwal (2017). S. Chand's Simplified Course in Ancient Indian History. S. Chand Publishing. ISBN 978-81-219-1853-4.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - 1998 District Census Report of [name of District].: Sindh. Population Census Organisation, Statistics Division, Government of Pakistan. 1999.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Kessler, P L. "Kingdoms of South Asia – Kingdoms of the Indus / Sindh". www.historyfiles.co.uk. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- Nicholas F. Gier, FROM MONGOLS TO MUGHALS: RELIGIOUS VIOLENCE IN INDIA 9TH–18TH CENTURIES, presented at the Pacific Northwest Regional Meeting American Academy of Religion, Gonzaga University, May 2006

- Maher, Mahim (27 March 2014). "From Zardaris to Makranis: How the Baloch came to Sindh". The Express Tribune. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- Ratcliffe, Susan (17 March 2011). Concise Oxford Dictionary of Quotations. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-956707-2.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Roger D. Long; Gurharpal Singh; Yunas Samad; Ian Talbot (8 October 2015), State and Nation-Building in Pakistan: Beyond Islam and Security, Routledge, pp. 102–, ISBN 978-1-317-44820-4

- Bhavnani, Nandita (2014). The Making of Exile: Sindhi Hindus and the Partition of India. Tranquebar Press. ISBN 978-93-84030-33-9.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Priya Kumar; Rita Kothari (2016). "Sindh, 1947 and Beyond". South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies. 39 (4): 776–777. doi:10.1080/00856401.2016.1244752.

- Aggarwal, Saaz (13 August 2022). "How refugees from Sindh rebuilt their lives – and India – after Partition". Scroll.in. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- Kamphorst, Janet (2008). In praise of death: history and poetry in medieval Marwar (South Asia). Leiden: Leiden University Press. ISBN 978-90-485-0603-3. OCLC 614596834.

- Ahmed Abdullah. "The People and The Land of Sindh". Archived from the original on 5 November 2010. Retrieved 7 January 2023 – via Scribd.

- ^ MacLean, Derryl L. (1989). Religion and Society in Arab Sind. BRILL. pp. 12–14, 77–78. ISBN 978-90-040-8551-0.

- Shu Hikosaka, G. John Samuel, Can̲ārttanam Pārttacārati (ed.), Buddhist themes in modern Indian literature, Inst. of Asian Studies, 1992, p. 268

- ^ "Pakistan Census Data" (PDF).

- "Partition and the "other" Sindhi". www.thenews.com.pk.

- Mehtab Ali Shah (1997). The foreign policy of Pakistan: ethnic impacts on diplomacy, 1971–1994. London: I B Tauris and Co Ltd. p. 46.

- "INDIA – Part I – Tables" (PDF). Census of India 1941. p. 90.

- "Population According to Religion" (PDF). Census of Pakistan, 1951. p. 8,22.

- Proceedings of the First Congress of Pakistan History & Culture held at the University of Islamabad, April 1973, Volume 1, University of Islamabad Press, 1975

- M. Ishaq, "Hakim Bin Jabala – An Heroic Personality of Early Islam", Journal of the Pakistan Historical Society, pp. 145–50, (April 1955).

- Derryl N. Maclean," Religion and Society in Arab Sind", p. 126, BRILL, (1989) ISBN 90-04-08551-3.

- Mirza Kalichbeg Fredunbeg, "The Chachnama", p. 43, The Commissioner's Press, Karachi (1900).

- Ibn Athir, Vol. 3, pp. 45–46, 381, as cited in: S. A. N. Rezavi, "The Shia Muslims", in History of Science, Philosophy and Culture in Indian Civilization, Vol. 2, Part. 2: "Religious Movements and Institutions in Medieval India", Chapter 13, Oxford University Press (2006).

- Ibn Sa'd, 8:346. The raid is noted by Baâdhurî, "fatooh al-Baldan" p. 432, and Ibn Khayyât, Ta'rîkh, 1:173, 183–84, as cited in: Derryl N. Maclean," Religion and Society in Arab Sind", p. 126, BRILL, (1989) ISBN 90-04-08551-3.

- Tabarî, 2:129, 143, 147, as cited in: Derryl N. Maclean," Religion and Society in Arab Sind", p. 126, Brill, (1989) ISBN 90-04-08551-3.

- Mazheruddin Siddiqui, "Muslim culture in Pakistan and India" in Kenneth W. Morgan, Islam, the Straight Path: Islam Interpreted by Muslims, Motilal Banarsidass Publ., 1987, p. 299

- Ahmed Abdulla, The historical background of Pakistan and its people, Tanzeem Publishers, 1973, p. 109

- Ansari, Sarah FD. Sufi saints and state power: the pirs of Sind, 1843–1947. No. 50. Cambridge University Press, 1992.

- Kamalakaran, Ajay. "In the story of Sindhi migration, Canary Islands played a small but important role". Scroll.in. Retrieved 13 January 2023.

- Peck, James (2004). Hindus on a rock. United Kingdom: Oxford Brookes University. p. 1.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - David, Maya Khemlani (2001). The Sindhi Hindus of London. Malaysia: University of Malaya.

- "They made a life in Hong Kong: Hindus on India's partition". South China Morning Post. 15 August 2019. Retrieved 15 January 2023.

- "Homepage of Sindhi Association of Hongkong & China". sindhishongkong.com. Retrieved 15 January 2023.

- Roshni. "Hong Kong Sindhis: Living in a Bubble!". Roshni Write Now. Retrieved 15 January 2023.

- Census of India, 1901: Baluchistan. 3 pts

- Dootio, Mazhar Ali (6 December 2018). "Sindhi culture and its importance". Daily Times. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- Sharma, Ram Nath; Sharma, Rajendra K. (1997). Anthropology. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. ISBN 978-81-7156-673-0.

The cultural marks of the Bronze Age are found in Baluchistan, Makran, Khurram, Jhalwan and Sindh

- Zhang, Sarah (5 September 2019). "A Burst of Clues to South Asians' Genetic Ancestry". The Atlantic. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- Manian, Ranjini (9 February 2011). Doing Business in India For Dummies. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-05163-4.

Gujarati, Marathi, Punjabi, and Sindhi. As far as dress is concerned, women in the north wear Sari and Shalwar Kameez, Chudidar-Kurta, and Lehenga-Kurta Men wear Pyjama-Kurta and Dhoti-Kurta

- Meena, R. P. Art, Culture and Heritage of India: for Civil Services Examination. New Era Publication.

Sindhi literature is very rich and oldest literature in the world's literatures

- Rahman, Tariq (1999). The Teaching of Sindhi and Sindhi Ethnicity. p. 1.

Sindhi is one of the most ancient languages of India. Indeed, the first language Muslims (Arabs) came in contact with when they entered India in large numbers was Sindhi. Thus several Arab writers mention that Sindhi was the language of people in al-Mansura, the capital of Sind. Indeed, the Rajah of Alra called Mahraj, whose kingdom was situated between Kashmir and Punjab, requested Amir Abdullah bin Umar, the ruler of al-Mansura, to send him someone to translate the Quran into his language around A.D. 882. The language is called 'Hindi' by Arab historians (in this case the author of Ajaib ul Hind) who often failed to distinguish between the different languages of India and put them all under the generic name of 'Hindi'. However, Syed Salman Nadwi, who calls this the first translation of the Quran into any Indian language suggests that this language might be Sindhi.

- Anwar, Tauseef (29 December 2016). "Sindhi Culture". PakPedia. Retrieved 4 January 2023.

- Harjani, Dayal N. (19 July 2018). Sindhi Roots & Rituals - Part 1. Notion Press. ISBN 978-1-64249-289-7.

They were the first Muslims to translate the Quran into the Sindhi language

- Sind Through the Centuries: An Introduction to Sind, a Progressive Province of Pakistan. Publicity and Publication Committee, Sind Through the Centuries Seminar. 1975.

During the long period of history, Sindhi language has absorbed influences of the old Iranian language during, It is also recorded that treatises were written in Sindhi on Astronomy, Medicine

- "Sindhi Music".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "Indigenous Sindhi Music Instruments".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "Sindhi music on the streets of Karachi". BBC. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ^ "An Introduction To Sindhi Dance And Music". Sindhi Khazana. Retrieved 9 January 2023.

- Reejhsinghani, Aroona (2004). Essential Sindhi Culturebook. Penguin Books India. ISBN 978-0-14-303201-4.

- "Sindhi Folk Dance Chhej - The Sindhu World Dance of Unity: Sindhi Group Dance: Cheti Chand: Bahrana: Jhulelal". thesindhuworld.com. 9 April 2021. Retrieved 9 January 2023.

- "The legend of Dodo Chanesar". The Express Tribune. 11 May 2012. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- "Legendary Folk Tales of Sindh - Moomal Rano" (PDF). Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- "Three-day Sindhi Culture Day family festival kicks off". www.thenews.com.pk. Retrieved 12 January 2023.

- "Sindhi Cultural Day". The Nation. 23 December 2022. Retrieved 12 January 2023.

- "Sindh Cultural Day being celebrated today across Pakistan". Daily Pakistan Global. 4 December 2022. Retrieved 12 January 2023.

- Report, Dawn (5 December 2022). "Sindhi Culture Day observed with zeal in province". DAWN.COM. Retrieved 12 January 2023.

- ^ "Festivals In Pakistan List of cultural events". Travel and Culture Services. Retrieved 12 January 2023.

- "Sindhi Festivals". Culturopedia. 7 April 2020. Retrieved 12 January 2023.

- "Sindhi Festivals - The Sindhu World Sindhi Cultural Heritage: Sindhi Folk Dance: Celebration". thesindhuworld.com. 8 May 2021. Retrieved 12 January 2023.

- ^ Reejhsinghani, Aroona (2004). Essential Sindhi Cookbook. Penguin Books India. ISBN 978-0-14-303201-4.

- Kent, Eliza F.; Kassam, Tazim R. (12 July 2013). Lines in Water: Religious Boundaries in South Asia. Syracuse University Press. ISBN 978-0-8156-5225-0.

- Reejhsinghani, Aroona (4 August 2004). The Essential Sindhi Cookbook. Penguin UK. ISBN 978-93-5118-094-4.

- Jillani, Maryam (2 April 2019). "Sindhi food: A vibrant cuisine hidden from the Pakistani and Indian public". DAWN.COM. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- "Sindhi Culture Day being celebrated across Sindh today". The Nation. 4 December 2022. Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- "Sindhi Culture Day being celebrated across Sindh today". Pakistan Today. 3 December 2022. Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- "Sindhi Cultural Day being celebrated today". www.radio.gov.pk. Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- "PM felicitates Sindh people on culture day celebrations". Associated Press of Pakistan. 4 December 2022. Retrieved 12 January 2023.

- "Canadian PM Justin Trudeau sends heartfelt greetings on Sindhi Cultural Day". WikiTech Library. 4 December 2022. Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- "Cultural Activity Archives - World Sindhi Congress World Sindhi Congress". World Sindhi Congress. Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- "Sindhi Culture Day completes first decade of celebrations with great gusto". www.thenews.com.pk. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- APP (4 December 2016). "Sindhi Culture Day celebrated in Sindh". The News International. Retrieved 7 December 2016.

- Hasan, Shazia (14 May 2022). "Showcasing local cultures, Sindh Craft Festival gets under way". DAWN.COM. Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- "Pakistan: Sindh CM celebrates Sindhi Culture Day with students". gulfnews.com. 3 December 2022. Retrieved 26 June 2023.

Sources

- Bherumal Mahirchand Advani, "Amilan-jo-Ahwal" – published in Sindhi, 1919

- Amilan-jo-Ahwal (1919) – translated into English in 2016 ("A History of the Amils") at sindhis

External links

| This section's use of external links may not follow Misplaced Pages's policies or guidelines. Please improve this article by removing excessive or inappropriate external links, and converting useful links where appropriate into footnote references. (December 2022) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

- SabSindhi-All About Sindhis, Music, Books, Magazines, People, Dictionary, Calendar, Keyboard

- Sindhi Sangat: promoting & preserving the Sindhi heritage, culture and language.

- Sindhi Jagat: All India Sindhi Consolidating Centre.

- Sindhi Surnames Origin – Trace your roots

- www.thesindhi.com

- www.worldsindhicongress.org

- Sindhi Association of North America

- Sindhi Association of Europe

| Demographics of India | |

|---|---|

| States | |

| Union territories | |

| Ethnic groups in Pakistan | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||

| History | |

|---|---|

| Government and politics | |

| Culture |

|

| Geography | |

| Education | |

| Sports | |

| Flora & fauna | |

| Sindhi media | |

| Sindhi websites | |

| Sindh tourism | |

| Sindhi nationalism | ||

|---|---|---|

| Active since 1972 | ||

| Historical States of Sindh |  | |

| Historic figures |

| |

| Modern figures | ||

| Culture | ||

| Poets | ||

| Contemporary controversies | ||

| Battles and conflicts | ||

| Political parties | ||

| Student organizations | ||

| Militant Organizations | ||

| Non profit organizations | ||