| Revision as of 19:47, 16 February 2023 editSemsûrî (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers62,367 edits Different image in infoboxTag: Visual edit← Previous edit | Revision as of 21:17, 16 February 2023 edit undo31.155.31.205 (talk) thTags: categories removed references removed Mobile edit Mobile web editNext edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Province of Turkey}} | {{Short description|Province of Turkey}} | ||

| ⚫ | {{pp-move-indef}}{{Infobox Turkey place|type=province|image_skyline=Tunceli location districts.png|image_caption=Map of Tunceli Province with its districts|leader_name=] (])|leader_title=]|area_code=0428<ref> {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110822080457/http://www.ttrehber.turktelekom.com.tr/trk-web/alankodlari.html |date=2011-08-22 }} {{in lang|tr}}</ref>|established_date=25 December 1935|Location in Turkey=<!-- government type, leaders -->}}'''Tunceli Province''' (]: Tunceli ili'','' {{lang-ku|Parêzgeha Dêrsim}}, ]: Dêsim wilayet, {{Lang-hy|Դերսիմի մարզ}}) formerly '''Dersim Province''', is located in the ] of ]. It was originally named Dersim Province (Dersim vilayeti), then demoted to a district (Dersim ]) and incorporated into ] in 1926.<ref> {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130801045931/http://www.tbmm.gov.tr/TBMM_Album/Cilt1/index.html|date=2013-08-01}}, Vol. 1, p. XXII, Dersim İli, 26.06.1926 tarih ve 404 sayılı Resmi Ceride'de yayımlanan 30.5.1926 tarih ve 877 sayılı Kanunla ilçeye dönüstürülerek Elazıg'a bağlanmıştır.</ref> | ||

| {{pp-move-indef}} | |||

| {{Infobox Turkey place | |||

| | type = province | |||

| |population_total=83645|population_as_of=2021| image_skyline = Munzur nehri Tunceli merkez ,.jpg | |||

| | image_caption = Munzur River runs through the province | |||

| | Location in Turkey = <!-- government type, leaders --> | |||

| | leader_title = ] | |||

| | leader_name = ] (]) | |||

| | area_code = 0428<ref> {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110822080457/http://www.ttrehber.turktelekom.com.tr/trk-web/alankodlari.html |date=2011-08-22 }} {{in lang|tr}}</ref> | |||

| | established_date = 25 December 1935 | |||

| }} | |||

| ⚫ | '''Tunceli Province''' (]: Tunceli ili'','' {{lang-ku|Parêzgeha Dêrsim}}, ]: Dêsim wilayet, {{Lang-hy|Դերսիմի մարզ}}) formerly '''Dersim Province''', is located in the ] of ]. It was originally named Dersim Province (Dersim vilayeti), then demoted to a district (Dersim ]) and incorporated into ] in 1926.<ref> {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130801045931/http://www.tbmm.gov.tr/TBMM_Album/Cilt1/index.html |

||

| Tunceli Province is surrounded by the provinces of ], ] and ]. The Province apart from the ], it is divided into seven districts named ], ], ], ], ], ] and ].{{Sfn|Tuncel|2012|p=380–381}} | Tunceli Province is surrounded by the provinces of ], ] and ]. The Province apart from the ], it is divided into seven districts named ], ], ], ], ], ] and ].{{Sfn|Tuncel|2012|p=380–381}} | ||

| The province had a population of 83,645 in 2021.<ref name="tuik">{{Cite web |title=Address-based population registration system (ADNKS) results dated 31 December 2021 |url=https://www.tuik.gov.tr/indir/duyuru/favori_raporlar.xlsx |access-date=20 December 2022 |publisher=] |language=tr |format=XLS}}</ref> | |||

| == Geography == | == Geography == | ||

| ] | |||

| {{See also|Munzur Valley National Park}} | {{See also|Munzur Valley National Park}} | ||

| ] | |||

| ] in ] |

] in ]]] | ||

| The adjacent provinces are ] to the north and west, ] to the south, and ] to the east. The province covers an area of {{convert|7774|sqkm|sqmi|abbr=on}} and has a population of 76,699. Tunceli is traversed by the northeasterly line of equal latitude and longitude. The ] is also situated in the province.<ref>{{Cite web |

The adjacent provinces are ] to the north and west, ] to the south, and ] to the east. The province covers an area of {{convert|7774|sqkm|sqmi|abbr=on}} and has a population of 76,699. Tunceli is traversed by the northeasterly line of equal latitude and longitude. The ] is also situated in the province.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Munzur Valley National Park {{!}} National Parks Of Turkey |url=http://www.nationalparksofturkey.org/munzur-valley-national-park-en |access-date=2020-04-11 |website=www.nationalparksofturkey.org |language=en}}</ref> | ||

| Tunceli Province is a plateau characterized by its high, thickly forested mountain ranges. The historical region of Dersim, which largely corresponds to Tunceli Province, lies roughly between the ] and ] rivers, both tributaries of the ].<ref name=": |

Tunceli Province is a plateau characterized by its high, thickly forested mountain ranges. The historical region of Dersim, which largely corresponds to Tunceli Province, lies roughly between the ] and ] rivers, both tributaries of the ].<ref name=":13">{{cite journal |last1=Arakelova |first1=Victoria |last2=Grigorian |first2=Christine |title=The Halvori Vank': An Armenian Monastery and a Zaza Sanctuary |url=https://www.academia.edu/8162093 |access-date=1 May 2018 |website=academia.edu}}</ref> | ||

| ].]] | ].]] | ||

| == Name == | == Name == | ||

| Tunceli, which is a modern name, literally means "bronze fist" in Turkish (''tunç'' meaning "bronze" and ''eli'' (in this context) meaning "fist"). It shares the name with the military operation that the ] was conducted under.<ref>{{Cite web |title=The Massacre in Dersim Still Haunts Kurds in Turkey |url=https://jacobin.com/2021/01/massacre-dersim-turkey-kurds-erdogan |access-date=2022-11-05 |website=jacobin.com |language=en-US}}</ref> | Tunceli, which is a modern name, literally means "bronze fist" in Turkish (''tunç'' meaning "bronze" and ''eli'' (in this context) meaning "fist"). It shares the name with the military operation that the ] was conducted under.<ref>{{Cite web |title=The Massacre in Dersim Still Haunts Kurds in Turkey |url=https://jacobin.com/2021/01/massacre-dersim-turkey-kurds-erdogan |access-date=2022-11-05 |website=jacobin.com |language=en-US}}</ref> | ||

| According to ], it is noteworthy that six centuries before Christ, Greek historians and geographers called the Dersim region Daranis, and in the ] of ], this region is called Zuza, and the term Zuza is similar to the word ], which is the "Kurdish dialect" spoken in Dersim and its region.{{Sfn|Dersimi|1952|p=1}} According to another thesis, estimated that the name Dersim (Der-sîm "silver gate" in ]) was given to the region, which frequently changed hands between the ] and ] during the Byzantine period.{{Sfn|Tuncel|2012|p=380–381}} It has been proposed that the name Dersim is connected with various placenames mentioned by ancient and classical writers, such as Daranis, Derxene (a district of ] mentioned by ]), and ] |

According to ], it is noteworthy that six centuries before Christ, Greek historians and geographers called the Dersim region Daranis, and in the ] of ], this region is called Zuza, and the term Zuza is similar to the word ], which is the "Kurdish dialect" spoken in Dersim and its region.{{Sfn|Dersimi|1952|p=1}} According to another thesis, estimated that the name Dersim (Der-sîm "silver gate" in ]) was given to the region, which frequently changed hands between the ] and ] during the Byzantine period.{{Sfn|Tuncel|2012|p=380–381}} It has been proposed that the name Dersim is connected with various placenames mentioned by ancient and classical writers, such as Daranis, Derxene (a district of ] mentioned by ]), and ]/Daranaghi (a district of Armenia mentioned by ], ], and ]).<ref name=":52">Korkmaz, M. (2012). . Ankara: Alter Yayıncılık, pp. 164{{En dash}}169. Archived from on 2022-05-04.</ref><ref name=":122">{{Cite encyclopedia |year=1977 |title=Daranaghi |encyclopedia=Soviet Armenian Encyclopedia |url=https://hy.wikisource.org/%D4%B7%D5%BB:%D5%80%D5%A1%D5%B5%D5%AF%D5%A1%D5%AF%D5%A1%D5%B6_%D5%8D%D5%B8%D5%BE%D5%A5%D5%BF%D5%A1%D5%AF%D5%A1%D5%B6_%D5%80%D5%A1%D5%B6%D6%80%D5%A1%D5%A3%D5%AB%D5%BF%D5%A1%D6%80%D5%A1%D5%B6_(Soviet_Armenian_Encyclopedia)_3.djvu/311 |last= |first= |volume=3 |pages=311 |language=hy}}</ref> One theory as to the origin of the name associates it with ].<ref name=":52" /> | ||

| One Armenian folk tradition derives the name Dersim from a certain 17th-century priest named Der Simon, who, fearing the maurading ], proposed that his parishioners convert to the Alevi faith of their Kurdish neighbors. The proposal was accepted, and the Armenian converts renamed their home region Dersimon in honor of their religious leader, which later transformed into Dersim.{{Sfn|Halajyan|1973|p=249–250}} | One Armenian folk tradition derives the name Dersim from a certain 17th-century priest named Der Simon, who, fearing the maurading ], proposed that his parishioners convert to the Alevi faith of their Kurdish neighbors. The proposal was accepted, and the Armenian converts renamed their home region Dersimon in honor of their religious leader, which later transformed into Dersim.{{Sfn|Halajyan|1973|p=249–250}} | ||

| == History == | == History == | ||

| ] dynasty]] | ] dynasty]] | ||

| === Antiquity === | === Antiquity === | ||

| Line 60: | Line 46: | ||

| == Demographics == | == Demographics == | ||

| ] family in 1915 from ] district, Tunceli |

] family in 1915 from ] district, Tunceli]] | ||

| ] tribal leaders of Tunceli (i.e Dersim) in 1895 called ''] ],'' Seyid İbrahim, second from the left, was the head of the Abbasan tribe and father of ] who organizator of ]]] | ] tribal leaders of Tunceli (i.e Dersim) in 1895 called ''] ],'' Seyid İbrahim, second from the left, was the head of the Abbasan tribe and father of ] who organizator of ]]] | ||

| Tunceli's (Dersim) language distribution is 69.5% ] and ], 29.8% ] and 0.74% ] in 1927, also according to Savaş Sertel, ] are majority people and Zazaki were more common than Kurdish.{{Sfn|Sertel|2014|p=8}} However, Ahmet Kerim Gültekin defined the province as predominantly ] Alevi.{{Sfn|Gültekin|2019|p=4}} According to Nicole, at least 50% of the population is Kurdish{{Sfn|Watts|2010|p=167}} and the province is considered a part of ].{{Sfn|Bois|Minorsky|MacKenzie|5=2002}} ] is the main dialect around Pertek, while ] is spoken in Hozat, Pülümür, Ovacık and Nazımiye. Both Kurmanji and Zaza is spoken in Tunceli town and Mazgirt.{{Sfn|Malmîsanij|1988|p=62–67}} The Dimli (or Zaza) people of Dersim are the descendants of the ] who migrated from the highlands of ] region of ] in the 10th–12th century.{{Sfn|Asatrian|1995|p=405–411}} The districts of ], ] and ] had a large Armenian population during the Ottoman period. A large part of this population must have been ] out of Anatolia with the deportation order of 1915. It is likely that the remaining population migrated to Western Anatolia.{{Sfn|Sertel|2014|p=8}} | Tunceli's (Dersim) language distribution is 69.5% ] and ], 29.8% ] and 0.74% ] in 1927, also according to Savaş Sertel, ] are majority people and Zazaki were more common than Kurdish.{{Sfn|Sertel|2014|p=8}} However, Ahmet Kerim Gültekin defined the province as predominantly ] Alevi.{{Sfn|Gültekin|2019|p=4}} According to Nicole, at least 50% of the population is Kurdish{{Sfn|Watts|2010|p=167}} and the province is considered a part of ].{{Sfn|Bois|Minorsky|MacKenzie|5=2002}} ] is the main dialect around Pertek, while ] is spoken in Hozat, Pülümür, Ovacık and Nazımiye. Both Kurmanji and Zaza is spoken in Tunceli town and Mazgirt.{{Sfn|Malmîsanij|1988|p=62–67}} The Dimli (or Zaza) people of Dersim are the descendants of the ] who migrated from the highlands of ] region of ] in the 10th–12th century.{{Sfn|Asatrian|1995|p=405–411}} The districts of ], ] and ] had a large Armenian population during the Ottoman period. A large part of this population must have been ] out of Anatolia with the deportation order of 1915. It is likely that the remaining population migrated to Western Anatolia.{{Sfn|Sertel|2014|p=8}} | ||

| The Kurdish and Zaza people of the region are divided into tribes. Of the 20 tribes in ], 17 are ] and 3 are ];{{Sfn|Dersimi|1952|p=46}} of the 8 tribes in ], 6 are Zazaki and 2 are Kurmanji;{{Sfn|Dersimi|1952|p=47}} of the 17 tribes in ], 15 are Zazaki and 2 are Kurmanji;{{Sfn|Dersimi|1952|p=48}} of the 13 tribes in ], 12 are Zazaki and 1 is Kurmanji;{{Sfn|Dersimi|1952|p=53}} of the 14 tribes in ] 11 are Zazaki and 3 are Kurmanji;{{Sfn|Dersimi|1952|p=56}} 16 of the 30 tribes in ] speak Kurmanji and 14 speak Zazaki;{{Sfn|Dersimi|1952|p=55}} while all of the 8 tribes in ] speak Kurmanji.{{Sfn|Dersimi|1952|p=50}} The Hozat included present-day ]. |

The Kurdish and Zaza people of the region are divided into tribes. Of the 20 tribes in ], 17 are ] and 3 are ];{{Sfn|Dersimi|1952|p=46}} of the 8 tribes in ], 6 are Zazaki and 2 are Kurmanji;{{Sfn|Dersimi|1952|p=47}} of the 17 tribes in ], 15 are Zazaki and 2 are Kurmanji;{{Sfn|Dersimi|1952|p=48}} of the 13 tribes in ], 12 are Zazaki and 1 is Kurmanji;{{Sfn|Dersimi|1952|p=53}} of the 14 tribes in ] 11 are Zazaki and 3 are Kurmanji;{{Sfn|Dersimi|1952|p=56}} 16 of the 30 tribes in ] speak Kurmanji and 14 speak Zazaki;{{Sfn|Dersimi|1952|p=55}} while all of the 8 tribes in ] speak Kurmanji.{{Sfn|Dersimi|1952|p=50}} The Hozat included present-day ]. | ||

| ===Alevis=== | ===Alevis=== | ||

| {{Further|Kurdish Alevism}} | {{Further|Kurdish Alevism}} | ||

| The Tunceli Province has played an important role in the revival of Kurdish Alevism.{{Sfn|Gültekin|2019|p=4}} Many believe Munzur, Dersim to be the heartland of the Alevi. Where holy places, all of which are natural features of the landscape, are found in abundance, and where the region's isolation has insulated it from the influence of Turkeys' dominant Sunni sect of Islam, helping to keep its unique Alevi character relatively pure.<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2015/06/28/travel/finding-paradise-in-turkeys-munzur-valley.html |

The Tunceli Province has played an important role in the revival of Kurdish Alevism.{{Sfn|Gültekin|2019|p=4}} Many believe Munzur, Dersim to be the heartland of the Alevi. Where holy places, all of which are natural features of the landscape, are found in abundance, and where the region's isolation has insulated it from the influence of Turkeys' dominant Sunni sect of Islam, helping to keep its unique Alevi character relatively pure.<ref>{{cite news |last=Benanav |first=Michael |date=26 June 2015 |title=Finding Paradise in Turkey's Munzur Valley |newspaper=The New York Times |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2015/06/28/travel/finding-paradise-in-turkeys-munzur-valley.html |url-status=live |access-date=1 May 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171017150031/https://www.nytimes.com/2015/06/28/travel/finding-paradise-in-turkeys-munzur-valley.html |archive-date=17 October 2017}}</ref> | ||

| ===Armenians of Tunceli=== | ===Armenians of Tunceli=== | ||

| According to Mihran Prgiç Gültekin, the head of the Union of Dersim Armenians, around 75% of the population in villages of Dersim are "converted Armenians."<ref name=" |

According to Mihran Prgiç Gültekin, the head of the Union of Dersim Armenians, around 75% of the population in villages of Dersim are "converted Armenians."<ref name="YY2">. ''Massis Post''. Retrieved 9 February 2023.</ref><ref>. ''Armenian Weekly''. "Mihran Prgiç Gültekin, the head of the Union of Dersim Armenians, estimates that about 75% of the village’s population are “converted Armenians."</ref> The greater part of hidden Armenians of Dersim, according Gultekin, is afraid that the nationalist regime may be back and may repress them. Currently over 200 families have announce their Armenian descent in Dersim, Gultekin said.<ref name="YY2" /><ref>. ''İnternet Haber''. (in Turkish). "Erkam Tufan, “Tunceli civarında çok fazla sayıda Kripto Ermeni olduğu söyleniyor bu doğru mudur?” şeklindeki sorusuna Ateşyan şu yanıtı verdi: “Doğrudur Tunceli'nin yüzde 90'ı belki dönme Ermeni'dir. Neden derseniz 30 yaşlarında bir çocuk geldi bana ve <nowiki>''</nowiki>benim köküm Ermeni<nowiki>''</nowiki> dedi. <nowiki>''</nowiki>Ben dönmek istiyorum<nowiki>''</nowiki> dedi. Ben de <nowiki>''</nowiki>ispatla dedim<nowiki>''</nowiki> ispatlayamadı, kabul etmedim. Ama inatla gitti geldi, vazgeçmedi. Gitti, geldi rahatsız etti beni, daha sonra babası aradı. Beyefendi dedi <nowiki>''</nowiki>ben belediye çalışıyorum emekli olayım bende İstanbul'a gelip döneceğim. Buradaki halkın yüzde 90'ı Ermeni'dir, lütfen kabul et<nowiki>''</nowiki> dedi. Bende kabul ettim ders aldı, vaftiz oldu, kilisemizin üyesi oldu.”"</ref> In 2015, a group of citizens in Dersim (Tunceli) established the Dersim Armenians and Alevis Friendship Association (DERADOST). The opening ceremony of the association was attended by Hüseyin Tunç, then Deputy Mayor of Tunceli, Yusuf Cengiz, President of Tunceli Chamber of Commerce and Industry, representatives of non-governmental organisations and some citizens.<ref>. ''Hürriyet''. (in Turkish). "Tunceli'de bir grup vatandaş, Dersimli Ermeniler ve Aleviler Dostluk Derneği (DERADOST) kurdu. Moğultay Mahallesi Ata Sokak’taki bir iş hanında kurulan derneğin açılışına Tunceli Belediye Başkan Yardımcısı Hüseyin Tunç, Tunceli Ticaret ve Sanayi Odası Başkanı Yusuf Cengiz, sivil toplum kuruluşu temsilcileri ile bazı vatandaşlar katıldı."</ref><ref>. ''Haberler''. (in Turkish). Tunceli'de bir grup vatandaş, Dersimli Ermeniler ve Aleviler Dostluk Derneği (DERADOST) kurdu. Moğultay Mahallesi Ata Sokak'taki bir iş hanında kurulan derneğin açılışına Tunceli Belediye Başkan Yardımcısı Hüseyin Tunç, Tunceli Ticaret ve Sanayi Odası Başkanı Yusuf Cengiz, sivil toplum kuruluşu temsilcileri ile bazı vatandaşlar katıldı."</ref> On the 100th anniversary of the Armenian Genocide, president of the association Serkan Sariataş said that the state should face its past history as soon as possible.<ref>. ''Ermeni Haber Ajansı''. (in Turkish). "Ermeni Soykırımı'nın 100. yılında Dersimli Ermeniler ve Aleviler Dostluk Derneği (DERADOST) Başkanı Serkan Sariataş, devletin bir an önce geçmiş tarihiyle yüzleşmesi gerektiğini söyledi."</ref> Through the 20th century, an many of Armenians living in the mountainous region of Dersim had converted to Alevism. During the Armenian genocide, many of the ] in the region were saved by their ] neighbors. | ||

| == Name changes == | == Name changes == | ||

| Before and after the ], any villages and towns deemed to have non-Turkish names were renamed and given Turkish names in order to ] any non-Turkish heritage heritage.{{Sfn|Nişanyan|2011|p=14}}{{Sfn|Tuncel|2000|p=1}}<ref>T.C İçişleri Bakanlığı İller İdaresi Genel Müdürlüğü (1968). .</ref> During the Turkish Republican era, the words Kurdistan and Kurds were banned. The Turkish government had disguised the presence of the Kurds statistically by categorizing them as '']''.{{Sfn|Hooglund|1996|p=95}}{{Sfn|Bartkus|1999|p=91}} | Before and after the ], any villages and towns deemed to have non-Turkish names were renamed and given Turkish names in order to ] any non-Turkish heritage heritage.{{Sfn|Nişanyan|2011|p=14}}{{Sfn|Tuncel|2000|p=1}}<ref>T.C İçişleri Bakanlığı İller İdaresi Genel Müdürlüğü (1968). .</ref> During the Turkish Republican era, the words Kurdistan and Kurds were banned. The Turkish government had disguised the presence of the Kurds statistically by categorizing them as '']''.{{Sfn|Hooglund|1996|p=95}}{{Sfn|Bartkus|1999|p=91}} | ||

| Linguist ] estimates that 4,000 Kurdish geographical locations have been changed (both Zazaki and Kurmanji).{{Sfn|Nişanyan|2011|p=54}} Prior to the name changes, Many villages in Tunceli had recognizably Armenian names, often in corrupted forms.<ref name=": |

Linguist ] estimates that 4,000 Kurdish geographical locations have been changed (both Zazaki and Kurmanji).{{Sfn|Nişanyan|2011|p=54}} Prior to the name changes, Many villages in Tunceli had recognizably Armenian names, often in corrupted forms.<ref name=":13" /><ref name=":22">{{Cite journal |last=Gasparyan |first=H. H. |date=1979 |title=Dersim (Patmaazgagrakan aknark) |trans-title=Dersim (historical-ethnographical outline) |url=https://arar.sci.am/dlibra/publication/190126/edition/172667/content |journal=Patma-Banasirakan Handes |language=hy |volume=2 |pages=195–210 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140306043324/http://hpj.asj-oa.am/3151/1/1979-2%28195%29.pdf |archive-date=2014-03-06}}</ref> The people of Tunceli have been actively fighting to get their province reverted to its old Kurdish name "Dersim". Turkey's ruling ] (AK Party) claimed they are working on what it called a “democratization package” that includes the restoration of the Kurdish name of the eastern province of Tunceli back to Dersim in early 2013, but there has been no updates or news of it since then.<ref>. ''Today's Zaman''. (in Turkish). "Turkey's ruling Justice and Development Party (AK Party) is working on what it called a “democratization package” that includes the restoration of the Kurdish name of the eastern province of Tunceli. The original name of the province was Dersim and was changed to Tunceli in 1935."</ref> The local authority decided to call it Dersim in May 2019, while the Governor said it was against the law to call it Dersim.<ref>. ''Ahval''. (in Turkish). "The local authority in Tunceli in eastern Turkey decided this month to call the city and the province by its Kurdish name–Dersim–saying the Turkish name, which means bronze fist, did not represent the culture, history or religious beliefs of an area often at odds with central government."</ref> | ||

| ] | |||

| == Politics == | == Politics == | ||

| ], who entered the election as the candidate of the ], was elected mayor of Tunceli with 32 per cent of the votes.<ref name=" |

], who entered the election as the candidate of the ], was elected mayor of Tunceli with 32 per cent of the votes.<ref name="NN2">. ''Liberation''. Retrieved 9 February 2023. "For the first time in the history of Turkey, communists will be administering the municipality of a province. In the municipal elections held on March 31, running as the Communist Party of Turkey (TKP) candidate on the Dersim Democratic People Solidarity (DDHD) ticket, Fatih Mehmet Maçoğlu won the mainly Kurdish province of Dersim in Eastern Turkey with 32 percent of the votes."</ref><ref>. ''Euronews''. Retrieved 9 February 2023. (in Turkish). "Yerel seçimlere Türkiye Komünist Partisi adayı olarak giren Maçoğlu, oyların yüzde 32,77'sini alarak Tunceli Belediye Başkanı seçilmişti."</ref> Thus, for the first time in the history of Turkey, ] began to govern the municipality of a province.<ref name="NN2" /> | ||

| == Education == | == Education == | ||

| Line 89: | Line 77: | ||

| == Places of interest == | == Places of interest == | ||

| ] in ], Tunceli |

] in ], Tunceli]] | ||

| Tunceli is known for its old buildings such as the Çelebi Ağa Mosque,<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.kulturportali.gov.tr/turkiye/tunceli/gezilecekyer/celebi-aga-camii |

Tunceli is known for its old buildings such as the Çelebi Ağa Mosque,<ref>{{Cite web |title=ÇELEBİ AĞA CAMİİ |url=http://www.kulturportali.gov.tr/turkiye/tunceli/gezilecekyer/celebi-aga-camii |access-date=2020-04-11 |website=Kültür Portalı}}</ref> Elti Hatun Mosque,<ref>{{Cite web |title=Pushover Analysis of Historical Elti Hatun Mosque |url=https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/4d52/7ed7db458b1531d9a21f86b79a9468054079.pdf |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200411222342/https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/4d52/7ed7db458b1531d9a21f86b79a9468054079.pdf |archive-date=11 April 2020 |access-date=11 April 2020 |website=Semantic Scholar |s2cid=194452128}}</ref> Mazgirt Castle,<ref>{{Cite book |last=Sinclair |first=T. A. |title=Eastern Turkey: An Architectural & Archaeological Survey, Volume III |date=31 December 1989 |publisher=Pindar Press |isbn=978-1-904597-78-0 |pages=148 |language=en}}</ref> ],<ref>{{cite web |title=Pertek Kalesi |url=http://www.tuncelikulturturizm.gov.tr/TR,57312/pertek-kalesi.html |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161020045215/http://www.tuncelikulturturizm.gov.tr/TR,57312/pertek-kalesi.html |archive-date=2016-10-20 |access-date=2016-10-19}}</ref> and the Derun-i Hisar Castle.<ref>{{cite web |title=Derun-i Hisar (Sağman) Kalesi |url=http://www.tuncelikulturturizm.gov.tr/TR,57313/derun-i-hisar-sagman-kalesi.html |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171201034311/http://www.tuncelikulturturizm.gov.tr/TR,57313/derun-i-hisar-sagman-kalesi.html |archive-date=2017-12-01 |access-date=2017-11-18}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=DERUN-İ HİSAR (SAĞMAN) KALESİ |url=http://www.kulturportali.gov.tr/turkiye/tunceli/gezilecekyer/derun-i-hisar-sagman-kalesi |access-date=2020-04-11 |website=Kültür Portalı}}</ref> | ||

| == Notable people == | == Notable people == | ||

| ], who was born in ], Tunceli on 925. He ruled as Byzantine Emperor from 969 to 976, an intuitive and successful general, he strengthened the Empire and expanded its borders during his reign.]] | ], who was born in ], Tunceli on 925. He ruled as Byzantine Emperor from 969 to 976, an intuitive and successful general, he strengthened the Empire and expanded its borders during his reign.]] | ||

| * ] (925–976)<ref>"Çemişgezek" in The Concise Dictionary of World Place-Names, 2005, by John Everett-Heath, Oxford University Press.</ref> - Byzantine emperor between 969 and 976 years | * ] (925–976)<ref>"Çemişgezek" in The Concise Dictionary of World Place-Names, 2005, by John Everett-Heath, Oxford University Press.</ref> - Byzantine emperor between 969 and 976 years | ||

| * ] (1863–1937) - Kurdish tribal leader and organizator of Dersim rebellion | * ] (1863–1937) - Kurdish tribal leader and organizator of Dersim rebellion | ||

| * {{Interlanguage link multi|Andranik Andréassian|lt=|hy|Անդրանիկ Անդրեասյան (գրող)}} (1909–1996) - Armenian author, editor and a survivor of Armenian genocide |

* {{Interlanguage link multi|Andranik Andréassian|lt=|hy|Անդրանիկ Անդրեասյան (գրող)}} (1909–1996) - Armenian author, editor and a survivor of Armenian genocide | ||

| * ] (1903–1995) - Armenian engineer, author, and a survivor of Armenian genocide | * ] (1903–1995) - Armenian engineer, author, and a survivor of Armenian genocide | ||

| * ] (1893–1973) - Kurdish nationalist writer, revolutionary and intellectual | * ] (1893–1973) - Kurdish nationalist writer, revolutionary and intellectual | ||

| Line 128: | Line 117: | ||

| == Sources == | == Sources == | ||

| * {{Cite encyclopedia |title=DIMLĪ |encyclopedia=Encyclopædia Iranica |last=Asatrian |first=Garnik |date=1995 |editor-last=Yarshater |editor-first=Ehsan |volume=VI. Fasc. 4 |pages=405–411 |isbn=978-0933273634 |quote=DIM(I)LĪ (or Zāzā), the indigenous name of an Iranian people living mainly in eastern Anatolia, in the Dersim region (present-day Tunceli) between Erzincan (see ARZENJĀN) in the north and the Muratsu (Morādsū, Arm. Aracani) in the south, the far western part of historical Upper Armenia (Barjr Haykʿ). The Deylamite origin of the Dimlīs is also indicated by the linguistic position of Dimlī (see below). The appearance of the Dimlī in the areas they now inhabit seems to have been connected, as their name suggests, with waves of migration of Deylamites ii from the highlands of Gīlān during the 10th-12th centuries.}} |

* {{Cite encyclopedia |title=DIMLĪ |encyclopedia=Encyclopædia Iranica |last=Asatrian |first=Garnik |date=1995 |editor-last=Yarshater |editor-first=Ehsan |volume=VI. Fasc. 4 |pages=405–411 |isbn=978-0933273634 |quote=DIM(I)LĪ (or Zāzā), the indigenous name of an Iranian people living mainly in eastern Anatolia, in the Dersim region (present-day Tunceli) between Erzincan (see ARZENJĀN) in the north and the Muratsu (Morādsū, Arm. Aracani) in the south, the far western part of historical Upper Armenia (Barjr Haykʿ). The Deylamite origin of the Dimlīs is also indicated by the linguistic position of Dimlī (see below). The appearance of the Dimlī in the areas they now inhabit seems to have been connected, as their name suggests, with waves of migration of Deylamites ii from the highlands of Gīlān during the 10th-12th centuries.}} | ||

| * {{Cite book |last=Bayır |first=Derya |title=Minorities and Nationalism in Turkish Law |date=2016 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-317-09579-8}} | * {{Cite book |last=Bayır |first=Derya |title=Minorities and Nationalism in Turkish Law |date=2016 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-317-09579-8}} | ||

| * {{Cite book |last=Cağaptay |first=Soner |title=Islam, Secularism and Nationalism in Modern Turkey: Who is a Turk? |date=2006 |publisher=Routledge |year= |isbn=978-1-134-17448-5 |location= |pages= |language=}} | * {{Cite book |last=Cağaptay |first=Soner |title=Islam, Secularism and Nationalism in Modern Turkey: Who is a Turk? |date=2006 |publisher=Routledge |year= |isbn=978-1-134-17448-5 |location= |pages= |language=}} | ||

| Line 136: | Line 125: | ||

| * {{Citation |last=Gültekin |first=Ahmet Kerim |title=Kurdish Alevism: Creating New Ways of Practicing the Religion |date=2019 |url= |pages=4 |type=PDF |publisher=University of Leipzig |quote=Tunceli, a small, Kurdish-Alevi-dominated province in Eastern Turkey, has played an important role in the revival of Kurdish Alevism.}} | * {{Citation |last=Gültekin |first=Ahmet Kerim |title=Kurdish Alevism: Creating New Ways of Practicing the Religion |date=2019 |url= |pages=4 |type=PDF |publisher=University of Leipzig |quote=Tunceli, a small, Kurdish-Alevi-dominated province in Eastern Turkey, has played an important role in the revival of Kurdish Alevism.}} | ||

| * {{Cite journal |last=Nişanyan |first=Sevan |author-link=Sevan Nişanyan |date=2011 |title=Hayali Coğrafyalar: Cumhuriyet Döneminde Türkiye'de Değiştirilen Yeradları |journal=TESEV Demokratikleşme Programı |type=PDF |language=tr |pages= |quote=}} | * {{Cite journal |last=Nişanyan |first=Sevan |author-link=Sevan Nişanyan |date=2011 |title=Hayali Coğrafyalar: Cumhuriyet Döneminde Türkiye'de Değiştirilen Yeradları |journal=TESEV Demokratikleşme Programı |type=PDF |language=tr |pages= |quote=}} | ||

| *{{cite journal |last=Tuncel |first=Harun |year=2000 |title=Türkiye'de İsmi Değiştirilen Köyler English: Renamed Villages in Turkey |url= |journal=Fırat University Journal of Social Science |language=tr |volume=10 |issue=2 |pages=1 |archive-url= |archive-date= |access-date= |quote=}} | * {{cite journal |last=Tuncel |first=Harun |year=2000 |title=Türkiye'de İsmi Değiştirilen Köyler English: Renamed Villages in Turkey |url= |journal=Fırat University Journal of Social Science |language=tr |volume=10 |issue=2 |pages=1 |archive-url= |archive-date= |access-date= |quote=}} | ||

| * {{Cite journal |last=Malmîsanij |first=Mehemed |date=1988 |title=Dımıli ve Kurmanci Lehçelerinin Köylere Göre Dağılımı |trans-title=Distribution of Dimili and Kurmanji Dialects by Villages |journal=Berhem |type=PDF |language=Turkish, Kurdish |volume=3 |pages=62–67}} | * {{Cite journal |last=Malmîsanij |first=Mehemed |date=1988 |title=Dımıli ve Kurmanci Lehçelerinin Köylere Göre Dağılımı |trans-title=Distribution of Dimili and Kurmanji Dialects by Villages |journal=Berhem |type=PDF |language=Turkish, Kurdish |volume=3 |pages=62–67}} | ||

| * {{cite book |last=Watts |first=Nicole F. |title=Activists in Office: Kurdish Politics and Protest in Turkey (Studies in Modernity and National Identity) |publisher=University of Washington Press |year=2010 |isbn=978-0-295-99050-7 |location=Seattle |page=167 |quote=}} |

* {{cite book |last=Watts |first=Nicole F. |title=Activists in Office: Kurdish Politics and Protest in Turkey (Studies in Modernity and National Identity) |publisher=University of Washington Press |year=2010 |isbn=978-0-295-99050-7 |location=Seattle |page=167 |quote=}} | ||

| * {{cite book |last=Hooglund |first=Eric |url= |title=Turkey: a Country Study |publisher=U.S. Government Print Office |year=1996 |isbn=978-0-8444-0864-4 |editor-last=Metz |editor-first=Helen Chapin |edition= |location=Washington, DC |page=95 |chapter=The Society and It's Environment |quote= |access-date=}} |

* {{cite book |last=Hooglund |first=Eric |url= |title=Turkey: a Country Study |publisher=U.S. Government Print Office |year=1996 |isbn=978-0-8444-0864-4 |editor-last=Metz |editor-first=Helen Chapin |edition= |location=Washington, DC |page=95 |chapter=The Society and It's Environment |quote= |access-date=}} | ||

| * {{cite book |last=Bartkus |first=Viva Ona |url= |title=The Dynamic of Secession |publisher=Cambridge University Press |year=1999 |isbn=978-0-521-65970-3 |edition= |location=New York, NY |pages=91 |quote= |access-date=}} |

* {{cite book |last=Bartkus |first=Viva Ona |url= |title=The Dynamic of Secession |publisher=Cambridge University Press |year=1999 |isbn=978-0-521-65970-3 |edition= |location=New York, NY |pages=91 |quote= |access-date=}} | ||

| * {{cite book |last1=Gerlach |first1=Christian |title=The Extermination of the European Jews |date=2016 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-0-521-88078-7 |page=401 |language=en |quote=But by far the bloodiest violence targeted Kurds during the Dersim uprising of 1937–38, when Turkish troops massacred about 30,000 people. |author1-link=}} |

* {{cite book |last1=Gerlach |first1=Christian |title=The Extermination of the European Jews |date=2016 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-0-521-88078-7 |page=401 |language=en |quote=But by far the bloodiest violence targeted Kurds during the Dersim uprising of 1937–38, when Turkish troops massacred about 30,000 people. |author1-link=}} | ||

| * {{Cite book |last=Halajyan |first=Gevorg |title=Dersimi hayeri azgagrutʻyuně, masn A |publisher=Haykakan SSH GA hratarakchʻutʻyun |year=1973 |location=Yerevan |pages=249–250 |language=hy |trans-title=Ethnography of the Dersim Armenians, part I}} |

* {{Cite book |last=Halajyan |first=Gevorg |title=Dersimi hayeri azgagrutʻyuně, masn A |publisher=Haykakan SSH GA hratarakchʻutʻyun |year=1973 |location=Yerevan |pages=249–250 |language=hy |trans-title=Ethnography of the Dersim Armenians, part I}} | ||

| * {{Cite book |last=Dersimi |first=Nuri |title=Kürdistan Tarihinde Dersim |publisher=Ani Matbaası |year=1952 |isbn=975-6876-44-1 |location=Aleppo |pages= |language=tr |quote= |author-link=Nuri Dersimi |orig-year=}} | * {{Cite book |last=Dersimi |first=Nuri |title=Kürdistan Tarihinde Dersim |publisher=Ani Matbaası |year=1952 |isbn=975-6876-44-1 |location=Aleppo |pages= |language=tr |quote= |author-link=Nuri Dersimi |orig-year=}} | ||

| * {{Cite journal |last1=Bois |first1=Th |last2=Minorsky |first2=V. |last3=MacKenzie |first3=D. N. |date=2002 |orig-date=1960 |title=Kurds, Kurdistān |url= |journal=Encyclopaedia of Islam |edition=2 |publisher=BRILL |doi= |isbn=9789004161214 |quote=}} | * {{Cite journal |last1=Bois |first1=Th |last2=Minorsky |first2=V. |last3=MacKenzie |first3=D. N. |date=2002 |orig-date=1960 |title=Kurds, Kurdistān |url= |journal=Encyclopaedia of Islam |edition=2 |publisher=BRILL |doi= |isbn=9789004161214 |quote=}} | ||

| == External links == | == External links == | ||

| * | * | ||

| * | * | ||

| Line 152: | Line 142: | ||

| * | * | ||

| * | * | ||

| {{Districts of Turkey | |||

| | provname = Tunceli | |||

| | image = Tunceli | |||

| }} | |||

| {{Provinces of Turkey}} | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Revision as of 21:17, 16 February 2023

Province of TurkeyProvince in Turkey| Tunceli Province | |

|---|---|

| Province | |

Map of Tunceli Province with its districts Map of Tunceli Province with its districts | |

| Country | Turkey |

| Established | 25 December 1935 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Fatih Mehmet Maçoğlu (TKP) |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (TRT) |

| Area code | 0428 |

Tunceli Province (Turkish: Tunceli ili, Template:Lang-ku, Zazaki: Dêsim wilayet, Template:Lang-hy) formerly Dersim Province, is located in the Eastern Anatolia Region of Turkey. It was originally named Dersim Province (Dersim vilayeti), then demoted to a district (Dersim kazası) and incorporated into Elazığ Province in 1926.

Tunceli Province is surrounded by the provinces of Bingöl, Elazığ and Erzincan. The Province apart from the central district, it is divided into seven districts named Çemişgezek, Hozat, Mazgirt, Nazımiye, Ovacık, Pertek and Pülümür.

Geography

See also: Munzur Valley National Park

The adjacent provinces are Erzincan to the north and west, Elazığ to the south, and Bingöl to the east. The province covers an area of 7,774 km (3,002 sq mi) and has a population of 76,699. Tunceli is traversed by the northeasterly line of equal latitude and longitude. The Munzur Valley National Park is also situated in the province.

Tunceli Province is a plateau characterized by its high, thickly forested mountain ranges. The historical region of Dersim, which largely corresponds to Tunceli Province, lies roughly between the Karasu and Murat rivers, both tributaries of the Euphrates.

Name

Tunceli, which is a modern name, literally means "bronze fist" in Turkish (tunç meaning "bronze" and eli (in this context) meaning "fist"). It shares the name with the military operation that the Dersim Massacre was conducted under.

According to Nuri Dersimi, it is noteworthy that six centuries before Christ, Greek historians and geographers called the Dersim region Daranis, and in the Behistun inscriptions of Darius the Great, this region is called Zuza, and the term Zuza is similar to the word Zaza, which is the "Kurdish dialect" spoken in Dersim and its region. According to another thesis, estimated that the name Dersim (Der-sîm "silver gate" in Persian) was given to the region, which frequently changed hands between the Sassanids and Byzantium during the Byzantine period. It has been proposed that the name Dersim is connected with various placenames mentioned by ancient and classical writers, such as Daranis, Derxene (a district of Armenia mentioned by Pliny), and Daranalis/Daranaghi (a district of Armenia mentioned by Ptolemy, Agathangelos, and Faustus of Byzantium). One theory as to the origin of the name associates it with Darius the Great.

One Armenian folk tradition derives the name Dersim from a certain 17th-century priest named Der Simon, who, fearing the maurading Celali rebels, proposed that his parishioners convert to the Alevi faith of their Kurdish neighbors. The proposal was accepted, and the Armenian converts renamed their home region Dersimon in honor of their religious leader, which later transformed into Dersim.

History

Antiquity

This region was known as Ishuva in the 2000s BC. As a result of the struggle of the Ishuva Kingdom, which was established by the Hurrians in the region, with the Hittites, this place passed under the rule of the Hittites towards the 1600s BC. Then it came under the domination of the Urartians and formed the westernmost part of the country of Urartu. After that, it was ruled by Medes and the Persian Achaemenid Empire, next it passed into the hands of the Alexander the Great, king of Macedon. During the reign of Tigranes the Great, the king of Armenia of the Artaxiad dynasty, Dersim was annexed to the kingdom of Armenia, even after the fall of the Artaxiad dynasty, Dersim remained loyal to them and did not submit to the Romans.

Medieval

After the acceptance of Christianity as the official religion in Armenia, as in many territories subject to Armenia, Dersim, the people resisted the influence of the new religion and adhered to their old religious traditions. After the Byzantine Empire occupied the western parts of Armenian state, they deported as many of the Dersimites as they could capture to Thrace and made these refugees serve as soldiers against the Bulgarian invasion. Despite all Byzantine "tricks", the people of Dersim were able to prevent the establishment of Byzantine influence in their neighbourhood. Also the Seljuks defeated Byzantine Empire in 1093 but the people of Dersim did not submit to the Seljuks. At the time of the establishment of the Safavid Empire, Shi'ism, the official sect of the Safavid Empire, had been able to spread to Dersim in a favourable manner. The Kurds of Dersim showed favour towards Shāh Ismā'īl I and agreed to cede the fortress of Kemah to Ismā'īl as a military base to facilitate the military movements of the Safavids, on condition that their sovereignty and independence would be respected by Ismā'īl.

Ottoman Empire rule

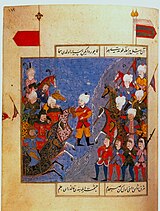

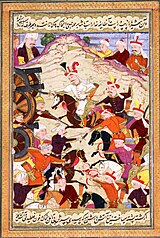

16th century Ottoman (left) and 17th century Safavid (right) miniatures depicting the battle of Chaldiran

16th century Ottoman (left) and 17th century Safavid (right) miniatures depicting the battle of Chaldiran

Although the Ottoman presence began to be felt in the region after Mehmed II the Conqueror defeated the Aq Qoyunlu in 1473, its incorporation into the Ottoman lands took place after the Battle of Chaldiran in 1514 during the reign of Selim the Grim. However, the harsh and rugged geographical structure of this place caused it to be in the hands of local administrators from time to time, away from state control. They displayed a rebellious situation during the weak periods of the central administrations. Even in 1895 between 1897, many Armenian fedayis took refuge in Dersim and benefited from the baht (of asylum) of the Dersimites and were able to protect themselves against the bathtubs of the Ottoman administration. Various Armenian and Alevi Zaza Kurdish rebellions took place in the region in the 1877, 1885, 1892, 1907, 1911, 1914 and 1916.

In Turkey

With the abolition of the Ottoman Empire, Turkey became the owner of the region. In 1937, an Alevi Kurdish revolt broke out in the region and was suppressed with the deaths of 30,000 Kurds. Following the Tunceli Law 1935, which demanded a more powerful government in the region, the Fourth Inspectorate-General (Umumi Müfettişlik, UM) was created in January 1936. The fourth UM span over the provinces of Elazığ, Erzincan, Bingöl and Tunceli, and was governed by a Governor Commander. Most of the employees in the municipality were to be filled with military personnel and the Governor-Commander had the authority to evacuate whole villages and resettle them in other parts. Also the juridical guarantees did not comply with the law in the other parts in Turkey. The trials were at most 15 days long and sentences could not be appealed. For a release, the Governor Commander had to give his consent. The application of the death penalty was under the authority of the Governor-Commander, while normally it would be the authority of the Grand National Assembly of Turkey to approve such a punishment. In 1946 the Tunceli Law was abolished and the state of emergency removed but the authority of the fourth UM was transferred to the military. The Inspectorates-General was dissolved in 1952 during the Government of the Democrat Party.

Demographics

Tunceli's (Dersim) language distribution is 69.5% Kurdish and Zazaki, 29.8% Turkish and 0.74% Armenian in 1927, also according to Savaş Sertel, Zazas are majority people and Zazaki were more common than Kurdish. However, Ahmet Kerim Gültekin defined the province as predominantly Kurdish Alevi. According to Nicole, at least 50% of the population is Kurdish and the province is considered a part of Turkish Kurdistan. Kurmanji Kurdish is the main dialect around Pertek, while Zazaki is spoken in Hozat, Pülümür, Ovacık and Nazımiye. Both Kurmanji and Zaza is spoken in Tunceli town and Mazgirt. The Dimli (or Zaza) people of Dersim are the descendants of the Deylamites who migrated from the highlands of Gilan region of Iran in the 10th–12th century. The districts of Mazgirt, Nazımiye and Çemişgezek had a large Armenian population during the Ottoman period. A large part of this population must have been deported out of Anatolia with the deportation order of 1915. It is likely that the remaining population migrated to Western Anatolia.

The Kurdish and Zaza people of the region are divided into tribes. Of the 20 tribes in Hozat, 17 are Zazaki and 3 are Kurmanji; of the 8 tribes in Çemişgezek, 6 are Zazaki and 2 are Kurmanji; of the 17 tribes in Ovacık, 15 are Zazaki and 2 are Kurmanji; of the 13 tribes in Pülümür, 12 are Zazaki and 1 is Kurmanji; of the 14 tribes in Nazımiye 11 are Zazaki and 3 are Kurmanji; 16 of the 30 tribes in Mazgirt speak Kurmanji and 14 speak Zazaki; while all of the 8 tribes in Pertek speak Kurmanji. The Hozat included present-day central district.

Alevis

Further information: Kurdish AlevismThe Tunceli Province has played an important role in the revival of Kurdish Alevism. Many believe Munzur, Dersim to be the heartland of the Alevi. Where holy places, all of which are natural features of the landscape, are found in abundance, and where the region's isolation has insulated it from the influence of Turkeys' dominant Sunni sect of Islam, helping to keep its unique Alevi character relatively pure.

Armenians of Tunceli

According to Mihran Prgiç Gültekin, the head of the Union of Dersim Armenians, around 75% of the population in villages of Dersim are "converted Armenians." The greater part of hidden Armenians of Dersim, according Gultekin, is afraid that the nationalist regime may be back and may repress them. Currently over 200 families have announce their Armenian descent in Dersim, Gultekin said. In 2015, a group of citizens in Dersim (Tunceli) established the Dersim Armenians and Alevis Friendship Association (DERADOST). The opening ceremony of the association was attended by Hüseyin Tunç, then Deputy Mayor of Tunceli, Yusuf Cengiz, President of Tunceli Chamber of Commerce and Industry, representatives of non-governmental organisations and some citizens. On the 100th anniversary of the Armenian Genocide, president of the association Serkan Sariataş said that the state should face its past history as soon as possible. Through the 20th century, an many of Armenians living in the mountainous region of Dersim had converted to Alevism. During the Armenian genocide, many of the Armenians in the region were saved by their Kurdish neighbors.

Name changes

Before and after the Dersim rebellion, any villages and towns deemed to have non-Turkish names were renamed and given Turkish names in order to suppress any non-Turkish heritage heritage. During the Turkish Republican era, the words Kurdistan and Kurds were banned. The Turkish government had disguised the presence of the Kurds statistically by categorizing them as Mountain Turks.

Linguist Sevan Nişanyan estimates that 4,000 Kurdish geographical locations have been changed (both Zazaki and Kurmanji). Prior to the name changes, Many villages in Tunceli had recognizably Armenian names, often in corrupted forms. The people of Tunceli have been actively fighting to get their province reverted to its old Kurdish name "Dersim". Turkey's ruling Justice and Development Party (AK Party) claimed they are working on what it called a “democratization package” that includes the restoration of the Kurdish name of the eastern province of Tunceli back to Dersim in early 2013, but there has been no updates or news of it since then. The local authority decided to call it Dersim in May 2019, while the Governor said it was against the law to call it Dersim.

Politics

Fatih Mehmet Maçoğlu, who entered the election as the candidate of the Communist Party of Turkey (TKP), was elected mayor of Tunceli with 32 per cent of the votes. Thus, for the first time in the history of Turkey, communists began to govern the municipality of a province.

Education

Tunceli University was established on May 22, 2008. Tunceli ranked first in education in the Life in Provinces Index announced by the Turkish Statistical Institute in January 2016.

Sports

Until 1990, there was a football team named Tuncelispor. This team returned as Dersimspor in the 2008–2009 season and was promoted to the 3rd League as the champion in the 3rd group of the 2014–15 Regional Amateur League. At the end of the 2016–17 Season, he was relegated to BAL. At the end of the 2018–2019 Season, Tunceli's football team in BAL placed 9th in the Dersim 62 Sports group. In addition, Pertek Belediyespor women's team ranked 6th in its group in the 2nd league of handball.

In the Football Turkish Cup, Dersim 62 Spor was eliminated by Adana Demirspor in the 4th round after eliminating 3 teams. Important sports facilities: Tunceli Atatürk Stadium (1.600), Tunceli Central Sports Hall (1.500), Tunceli Olympic Swimming Pool (500).

Places of interest

Tunceli is known for its old buildings such as the Çelebi Ağa Mosque, Elti Hatun Mosque, Mazgirt Castle, Pertek Castle, and the Derun-i Hisar Castle.

Notable people

- John I Tzimiskes (925–976) - Byzantine emperor between 969 and 976 years

- Seyid Riza (1863–1937) - Kurdish tribal leader and organizator of Dersim rebellion

- Andranik Andréassian [hy] (1909–1996) - Armenian author, editor and a survivor of Armenian genocide

- Vazken Andréassian (1903–1995) - Armenian engineer, author, and a survivor of Armenian genocide

- Nuri Dersimi (1893–1973) - Kurdish nationalist writer, revolutionary and intellectual

- Aurora Mardiganian (1901–1994) - Armenian author, actress, and a survivor of the Armenian genocide

- Sait Kırmızıtoprak [ku] (1935–1971) - Kurdish nationalist writer and revolutionary

- Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu (1948) - economist, retired civil servant, social democratic politician and leader of the Republican People's Party

- Alican Önlü (1967) - Kurdish politician

- Sakine Cansız (1958–2013) - Kurdish activist, co-founder of the Kurdistan Workers' Party

- Volga Sorgu [tr] (1981) - Zaza movie and serial actor

- Edibe Şahin (1960) - Kurdish politician, former mayor of the municipality of Tunceli.

- Kamer Genç (1940–2016) - Turkish politician

- Hülya Oran (1978) - Kurdish miliant, one of leaders of Kurdistan Workers' Party and is the co-chair of the Kurdistan Communities Union

- Hozan Diyar (1966) - Kurdish singer

- Hüseyin Aygün (1970) - Zaza lawyer and politician

- Ali Haydar Kaytan (1952–2021) - Kurdish miliant, co-founder of the Kurdistan Workers' Party

- Aynur Doğan (1975) - Kurdish singer and songwriter

- Fatih Mehmet Maçoğlu (1968) - Kurdish communist politician, currently the mayor of Tunceli with Communist Party of Turkey (TKP) ticket

- Ferhat Tunç (1964) - Kurdish singer, songwriter and musician

Originating from Tunceli

- Dilan Yeşilgöz-Zegerius (1977) - Dutch politician of Kurdish origin, current Minister of Justice and Security in Netherlands

- Yıldız Tilbe (1966) - singer of Kurdish origin

- Turgut Özal (1927–1993) - 8th president of Turkey, he was of mixed Turkish and Kurdish descent

- Gültan Kışanak (1961) - Kurdish journalist, author and politician

- Zuhal Demir (1980) - Belgian lawyer and politician of Kurdish origin, current minister of environment, justice, tourism and energy in Flanders, Belgium

References

- Area codes page of Turkish Telecom website Archived 2011-08-22 at the Wayback Machine (in Turkish)

- Album of the Grand National Assembly of Turkey Archived 2013-08-01 at the Wayback Machine, Vol. 1, p. XXII, Dersim İli, 26.06.1926 tarih ve 404 sayılı Resmi Ceride'de yayımlanan 30.5.1926 tarih ve 877 sayılı Kanunla ilçeye dönüstürülerek Elazıg'a bağlanmıştır.

- ^ Tuncel 2012, p. 380–381.

- "Munzur Valley National Park | National Parks Of Turkey". www.nationalparksofturkey.org. Retrieved 2020-04-11.

- ^ Arakelova, Victoria; Grigorian, Christine. "The Halvori Vank': An Armenian Monastery and a Zaza Sanctuary". academia.edu. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- "The Massacre in Dersim Still Haunts Kurds in Turkey". jacobin.com. Retrieved 2022-11-05.

- Dersimi 1952, p. 1.

- ^ Korkmaz, M. (2012). Deylem’den Dersim’e Dersimliler. Ankara: Alter Yayıncılık, pp. 164–169. Archived from the original on 2022-05-04.

- "Daranaghi". Soviet Armenian Encyclopedia (in Armenian). Vol. 3. 1977. p. 311.

- Halajyan 1973, p. 249–250.

- ^ Dersimi 1952, p. 73.

- Dersimi 1952, p. 73–74.

- ^ Dersimi 1952, p. 74.

- Dersimi 1952, p. 41.

- Gerlach 2016, p. 401.

- Cağaptay 2006, p. 108–110.

- Bayır 2016, p. 139–141.

- Faroqhi 2008, p. 343.

- ^ Sertel 2014, p. 8.

- ^ Gültekin 2019, p. 4.

- Watts 2010, p. 167.

- Bois et al. 2002.

- Malmîsanij 1988, p. 62–67.

- Asatrian 1995, p. 405–411.

- Dersimi 1952, p. 46.

- Dersimi 1952, p. 47.

- Dersimi 1952, p. 48.

- Dersimi 1952, p. 53.

- Dersimi 1952, p. 56.

- Dersimi 1952, p. 55.

- Dersimi 1952, p. 50.

- Benanav, Michael (26 June 2015). "Finding Paradise in Turkey's Munzur Valley". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 17 October 2017. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- ^ "Mihran Gultekin: Dersim Armenians Re-Discovering Their Ancestral Roots". Massis Post. Retrieved 9 February 2023.

- "Documentary on Islamized Armenians of Dersim Screened at Columbia University". Armenian Weekly. "Mihran Prgiç Gültekin, the head of the Union of Dersim Armenians, estimates that about 75% of the village’s population are “converted Armenians."

- "Tunceli'nin yüzde 90'ı dönme Ermeni'dir". İnternet Haber. (in Turkish). "Erkam Tufan, “Tunceli civarında çok fazla sayıda Kripto Ermeni olduğu söyleniyor bu doğru mudur?” şeklindeki sorusuna Ateşyan şu yanıtı verdi: “Doğrudur Tunceli'nin yüzde 90'ı belki dönme Ermeni'dir. Neden derseniz 30 yaşlarında bir çocuk geldi bana ve ''benim köküm Ermeni'' dedi. ''Ben dönmek istiyorum'' dedi. Ben de ''ispatla dedim'' ispatlayamadı, kabul etmedim. Ama inatla gitti geldi, vazgeçmedi. Gitti, geldi rahatsız etti beni, daha sonra babası aradı. Beyefendi dedi ''ben belediye çalışıyorum emekli olayım bende İstanbul'a gelip döneceğim. Buradaki halkın yüzde 90'ı Ermeni'dir, lütfen kabul et'' dedi. Bende kabul ettim ders aldı, vaftiz oldu, kilisemizin üyesi oldu.”"

- "Tunceli'de Ermeni ve Alevi dostluk derneği kurdu". Hürriyet. (in Turkish). "Tunceli'de bir grup vatandaş, Dersimli Ermeniler ve Aleviler Dostluk Derneği (DERADOST) kurdu. Moğultay Mahallesi Ata Sokak’taki bir iş hanında kurulan derneğin açılışına Tunceli Belediye Başkan Yardımcısı Hüseyin Tunç, Tunceli Ticaret ve Sanayi Odası Başkanı Yusuf Cengiz, sivil toplum kuruluşu temsilcileri ile bazı vatandaşlar katıldı."

- "Tunceli'de Ermeni ve Alevi Dostluk Derneği Kurdu". Haberler. (in Turkish). Tunceli'de bir grup vatandaş, Dersimli Ermeniler ve Aleviler Dostluk Derneği (DERADOST) kurdu. Moğultay Mahallesi Ata Sokak'taki bir iş hanında kurulan derneğin açılışına Tunceli Belediye Başkan Yardımcısı Hüseyin Tunç, Tunceli Ticaret ve Sanayi Odası Başkanı Yusuf Cengiz, sivil toplum kuruluşu temsilcileri ile bazı vatandaşlar katıldı."

- "DERADOST başkanından Erdoğan ile Davutoğlu'na Ermeni Soykırımı çağrısı". Ermeni Haber Ajansı. (in Turkish). "Ermeni Soykırımı'nın 100. yılında Dersimli Ermeniler ve Aleviler Dostluk Derneği (DERADOST) Başkanı Serkan Sariataş, devletin bir an önce geçmiş tarihiyle yüzleşmesi gerektiğini söyledi."

- Nişanyan 2011, p. 14.

- Tuncel 2000, p. 1.

- T.C İçişleri Bakanlığı İller İdaresi Genel Müdürlüğü (1968). "Köylerimiz".

- Hooglund 1996, p. 95.

- Bartkus 1999, p. 91.

- Nişanyan 2011, p. 54.

- Gasparyan, H. H. (1979). "Dersim (Patmaazgagrakan aknark)" [Dersim (historical-ethnographical outline)] (PDF). Patma-Banasirakan Handes (in Armenian). 2: 195–210. Archived from the original on 2014-03-06.

- "After 78 years, Turkey to restore Tunceli’s original name". Today's Zaman. (in Turkish). "Turkey's ruling Justice and Development Party (AK Party) is working on what it called a “democratization package” that includes the restoration of the Kurdish name of the eastern province of Tunceli. The original name of the province was Dersim and was changed to Tunceli in 1935."

- "A short history of Turkification: From Dersim to Tunceli". Ahval. (in Turkish). "The local authority in Tunceli in eastern Turkey decided this month to call the city and the province by its Kurdish name–Dersim–saying the Turkish name, which means bronze fist, did not represent the culture, history or religious beliefs of an area often at odds with central government."

- ^ "Communist Party of Turkey (TKP) wins Dersim province in local elections". Liberation. Retrieved 9 February 2023. "For the first time in the history of Turkey, communists will be administering the municipality of a province. In the municipal elections held on March 31, running as the Communist Party of Turkey (TKP) candidate on the Dersim Democratic People Solidarity (DDHD) ticket, Fatih Mehmet Maçoğlu won the mainly Kurdish province of Dersim in Eastern Turkey with 32 percent of the votes."

- "Tunceli'yi kazanan TKP'li Maçoğlu'na 'söylenemeyecek güvenlik gerekçesi' ile mazbatası verilmedi". Euronews. Retrieved 9 February 2023. (in Turkish). "Yerel seçimlere Türkiye Komünist Partisi adayı olarak giren Maçoğlu, oyların yüzde 32,77'sini alarak Tunceli Belediye Başkanı seçilmişti."

- "Tunceli University Signs Protocol with 4 American Universities". Turkish Daily Mail. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- "Eğitimde en iyi il belli oldu!". Radikal. Retrieved 9 February 2023.

- "Tunceli'ye yeni futbol kulübü: Dersimspor...". CNN Türk. Retrieved 9 February 2023.

- "ÇELEBİ AĞA CAMİİ". Kültür Portalı. Retrieved 2020-04-11.

- "Pushover Analysis of Historical Elti Hatun Mosque" (PDF). Semantic Scholar. S2CID 194452128. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 April 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- Sinclair, T. A. (31 December 1989). Eastern Turkey: An Architectural & Archaeological Survey, Volume III. Pindar Press. p. 148. ISBN 978-1-904597-78-0.

- "Pertek Kalesi". Archived from the original on 2016-10-20. Retrieved 2016-10-19.

- "Derun-i Hisar (Sağman) Kalesi". Archived from the original on 2017-12-01. Retrieved 2017-11-18.

- "DERUN-İ HİSAR (SAĞMAN) KALESİ". Kültür Portalı. Retrieved 2020-04-11.

- "Çemişgezek" in The Concise Dictionary of World Place-Names, 2005, by John Everett-Heath, Oxford University Press.

- "Star'daki Yıldız Tilbe'nin Programında Türk-Kürt Gerginliği...". Haber Vitrini. (in Turkish). Retrieved 9 February 2023. "Programın ilerki bölümlerinde Yıldız Tilbe, “Ulaştırma Bakanından uyarı gelmiş. Benim anam Tuncelili, hem Zaza hem Kürt, babam Ağrılı Kürt. Ben bu topraklarda doğdum, büyüdüm. Kürt neyse benim için Türk de odur, Laz da odur, Çerkez de odur. Hiç bir farkı yoktur birbirinden asla” dedi."

- "Çemişgezek'e bir gelen geri dönmek istemiyor". Sabah. (in Turkish). Retrieved 9 February 2023. "8. Cumhurbaşkanı Turgut Özal'ın annesi Hafize Özal, Çemişgezek Mezire Köyü doğumlu."

- "Turgut Özal'ı rahmetle anıyoruz". Yeni Akit. (in Turkish). Retrieved 9 February 2023. "Babası Malatya/Çırmıktı'lı Ünlüoğulları'ndan banka memuru Mehmet Sıddık Özal, annesi ise Tunceli Çemişgezekli, ilkokul öğretmeni Hafize Hanım (d. 1906 - ö. 1988) olan Turgut Özal kısmen Kürt kökenlidir."

- "Gültan Kışanak Kimdir?". Bianet. (in Turkish). 9 February 2023. "Ailesi zamanında Dersim'den göçerek Elazığ'ın merkez köylerinden Sünköy'e yerleşmiş bulunan Ağuce aşiretine mensuptur."

- "Belçika’nın Kürt asıllı bakanı Zuhal Demir tehdit edildi". Ahval. (in Turkish). Retrieved 9 February 2023. "Tunceli ve Elazığ kökenli, maden işçisi bir babanın üçüncü çocuğu olan Zuhal Demir, 12 Mart 1980'de Belçika'nın Genk kentinde dünyaya geldi."

Sources

- Asatrian, Garnik (1995). "DIMLĪ". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. VI. Fasc. 4. pp. 405–411. ISBN 978-0933273634.

DIM(I)LĪ (or Zāzā), the indigenous name of an Iranian people living mainly in eastern Anatolia, in the Dersim region (present-day Tunceli) between Erzincan (see ARZENJĀN) in the north and the Muratsu (Morādsū, Arm. Aracani) in the south, the far western part of historical Upper Armenia (Barjr Haykʿ). The Deylamite origin of the Dimlīs is also indicated by the linguistic position of Dimlī (see below). The appearance of the Dimlī in the areas they now inhabit seems to have been connected, as their name suggests, with waves of migration of Deylamites ii from the highlands of Gīlān during the 10th-12th centuries.

- Bayır, Derya (2016). Minorities and Nationalism in Turkish Law. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-09579-8.

- Cağaptay, Soner (2006). Islam, Secularism and Nationalism in Modern Turkey: Who is a Turk?. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-17448-5.

- Faroqhi, Suraiya N. (2008). "Guildsmen and handicraft producers". In Faroqhi, Suraiya N. (ed.). The Cambridge History of Turkey. Vol. 3. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-62096-3.

- Tuncel, Metin (2012). "Tunceli". TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi (in Turkish). Vol. 41. pp. 380–381.

- Sertel, Savaş (2014). "Türkiye Cumhuriyeti'nin İlk Genel Nüfus Sayımına Göre Dersim Bölgesinde Demografik Yapı". Fırat Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi (in Turkish). 24 (1). Elâzığ: 8. doi:10.18069/fusbed.82073. ISSN 1300-9702.

- Gültekin, Ahmet Kerim (2019), Kurdish Alevism: Creating New Ways of Practicing the Religion (PDF), University of Leipzig, p. 4,

Tunceli, a small, Kurdish-Alevi-dominated province in Eastern Turkey, has played an important role in the revival of Kurdish Alevism.

- Nişanyan, Sevan (2011). "Hayali Coğrafyalar: Cumhuriyet Döneminde Türkiye'de Değiştirilen Yeradları". TESEV Demokratikleşme Programı (PDF) (in Turkish).

- Tuncel, Harun (2000). "Türkiye'de İsmi Değiştirilen Köyler English: Renamed Villages in Turkey". Fırat University Journal of Social Science (in Turkish). 10 (2): 1.

- Malmîsanij, Mehemed (1988). "Dımıli ve Kurmanci Lehçelerinin Köylere Göre Dağılımı" [Distribution of Dimili and Kurmanji Dialects by Villages]. Berhem (PDF) (in Turkish and Kurdish). 3: 62–67.

- Watts, Nicole F. (2010). Activists in Office: Kurdish Politics and Protest in Turkey (Studies in Modernity and National Identity). Seattle: University of Washington Press. p. 167. ISBN 978-0-295-99050-7.

- Hooglund, Eric (1996). "The Society and It's Environment". In Metz, Helen Chapin (ed.). Turkey: a Country Study. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Print Office. p. 95. ISBN 978-0-8444-0864-4.

- Bartkus, Viva Ona (1999). The Dynamic of Secession. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-521-65970-3.

- Gerlach, Christian (2016). The Extermination of the European Jews. Cambridge University Press. p. 401. ISBN 978-0-521-88078-7.

But by far the bloodiest violence targeted Kurds during the Dersim uprising of 1937–38, when Turkish troops massacred about 30,000 people.

- Halajyan, Gevorg (1973). Dersimi hayeri azgagrutʻyuně, masn A [Ethnography of the Dersim Armenians, part I] (in Armenian). Yerevan: Haykakan SSH GA hratarakchʻutʻyun. pp. 249–250.

- Dersimi, Nuri (1952). Kürdistan Tarihinde Dersim (in Turkish). Aleppo: Ani Matbaası. ISBN 975-6876-44-1.

- Bois, Th; Minorsky, V.; MacKenzie, D. N. (2002) . "Kurds, Kurdistān". Encyclopaedia of Islam (2 ed.). BRILL. ISBN 9789004161214.