| Revision as of 23:15, 6 February 2024 edit204.152.164.5 (talk) Removal of outdated or duplicated information. The research is constantly ongoing. Detailed research information is moved to the stuttering therapy page, as it does not belong on generic stuttering article← Previous edit | Revision as of 23:35, 6 February 2024 edit undo204.152.164.5 (talk) Add source and clear up outdated informationNext edit → | ||

| Line 55: | Line 55: | ||

| Others have developed ] and encourage other stutterers to take pride in their stutter and to find how it has been beneficial for them. | Others have developed ] and encourage other stutterers to take pride in their stutter and to find how it has been beneficial for them. | ||

| ==== Associated conditions ==== | ==== Associated conditions ==== | ||

| Line 153: | Line 152: | ||

| ==Prognosis== | ==Prognosis== | ||

| Among preschoolers{{vague|date=March 2023}} with stuttering, the ] for recovery is |

Among preschoolers{{vague|date=March 2023}} with stuttering, the ] for recovery is about 65% to 87.5% of preschoolers who stutter recover spontaneously by 7 years of age or within the first 2 years of stuttering,<ref name="Sander and Osborne">{{cite journal |last1=Sander |first1=RW |last2=Osborne |first2=CA |title=Stuttering: Understanding and Treating a Common Disability. |journal=American Family Physician |date=1 November 2019 |volume=100 |issue=9 |pages=556–560 |pmid=31674746}}</ref><ref name="fn 30">{{cite journal |author1=Yairi, E.|author2= Ambrose, N.|title=Onset of stuttering in preschool children: selected factors |journal=Journal of Speech and Hearing Research |volume=35 |issue=4 |pages=782–8 |year=1992 |pmid=1405533 |doi=10.1044/jshr.3504.782}}</ref><ref name="fn 31">{{cite journal|author=Yairi, E.|year=1993|title=Epidemiologic and other considerations in treatment efficacy research with preschool-age children who stutter|journal=Journal of Fluency Disorders|volume=18|pages=197–220|doi=10.1016/0094-730X(93)90007-Q|issue=2–3}}</ref> and about 74% recover by their early teens.<ref name="Ward16">{{harvnb|Ward|2006|p= 16}}</ref> In particular, girls seem to recover more often.<ref name="Ward16"/><ref name="fn 34">{{cite journal|author= Yairi, E|title=On the Gender Factor in Stuttering|journal=Stuttering Foundation of America Newsletter|date=Fall 2005|page= 5}}</ref> | ||

| ⚫ | Prognosis is guarded with later age of onset: children who start stuttering at age 3½ years or later,<ref name="Yairi2005"/> and/or duration of greater than 6–12 months since onset, that is, once stuttering has become established, about 18% of children who stutter after five years recover spontaneously.<ref name="fn 32">{{cite journal |author=Andrews, G. |author2=Craig, A. |author3=Feyer, A. M. |author4=Hoddinott, S. |author5=Howie, P. |author6=Neilson, M. |title=Stuttering: a review of research findings and theories circa 1982 |journal=The Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders |volume=48 |issue=3 |pages=226–46 |year=1983 |pmid=6353066 |doi=10.1044/jshd.4803.226}}</ref> Stuttering that persists after the age of seven is classified as persistent stuttering, and is associated with a much lower chance of recovery.<ref name="Sander and Osborne" /> | ||

| Prognosis is guarded with later age of onset: children who start stuttering at age 3½ years or later,<ref name="Yairi2005"/> | |||

| ⚫ | and duration of greater than 6–12 months since onset, that is, once stuttering has become established, |

||

| For adults who stutter, there is no known cure,<ref name="Ward16"/> though they may make partial recovery or even complete recovery with intervention. People who stutter often learn to stutter less severely, though others may make no progress with therapy.<ref name="Guitar7"/> | |||

| Emotional sequelae associated with stuttering primarily relates to state-dependent anxiety related to the speech disorder itself. However, this is typically isolated to social contexts that require speaking, is not a trait anxiety, and this anxiety does not persist if stuttering remits spontaneously. Research attempting to correlate stuttering with generalized or state anxiety, personality profiles, trauma history, or decreased IQ have failed to find adequate empirical support for any of these claims. | |||

| ==Epidemiology== | ==Epidemiology== | ||

| The lifetime ], or the proportion of individuals expected to stutter at one time in their lives, is about 5%,<ref name="Mansson2000">{{cite journal|author= Mansson, H.|year=2000|title=Childhood stuttering: Incidence and development|journal=Journal of Fluency Disorders|volume=25|issue=1|pages=47–57|doi=10.1016/S0094-730X(99)00023-6}}</ref> and overall males are affected two to five times more often than females.<ref name="craig2005"/><ref name="Yairi96">{{cite journal|author= Yairi, E |author2=Ambrose, N |author3=Cox, N|year=1996|title=Genetics of stuttering: a critical review|journal=Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research|volume= 39|issue=4 |pages=771–784|doi=10.1044/jshr.3904.771|pmid=8844557 }}</ref><ref name="fn 28">{{cite journal |author=Kloth, S |author2=Janssen, P |author3=Kraaimaat, F |author4=Brutten, G |year = 1995 |title = Speech-motor and linguistic skills of young people who stutter prior to onset |journal=Journal of Fluency Disorders |issue=2 |pages=157–70 | doi=10.1016/0094-730X(94)00022-L | volume = 20 |hdl=2066/21168 |s2cid=146130424 |hdl-access=free }}</ref> |

The lifetime ], or the proportion of individuals expected to stutter at one time in their lives, is about 5%,<ref name="Mansson2000">{{cite journal|author= Mansson, H.|year=2000|title=Childhood stuttering: Incidence and development|journal=Journal of Fluency Disorders|volume=25|issue=1|pages=47–57|doi=10.1016/S0094-730X(99)00023-6}}</ref> and overall males are affected two to five times more often than females.<ref name="craig2005"/><ref name="Yairi96">{{cite journal|author= Yairi, E |author2=Ambrose, N |author3=Cox, N|year=1996|title=Genetics of stuttering: a critical review|journal=Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research|volume= 39|issue=4 |pages=771–784|doi=10.1044/jshr.3904.771|pmid=8844557 }}</ref><ref name="fn 28">{{cite journal |author=Kloth, S |author2=Janssen, P |author3=Kraaimaat, F |author4=Brutten, G |year = 1995 |title = Speech-motor and linguistic skills of young people who stutter prior to onset |journal=Journal of Fluency Disorders |issue=2 |pages=157–70 | doi=10.1016/0094-730X(94)00022-L | volume = 20 |hdl=2066/21168 |s2cid=146130424 |hdl-access=free }}</ref>As seen in children who have just begun stuttering, there is an equivalent number of boys and girls who stutter. Still, the sex ratio appears to widen as children grow: among preschoolers, boys who stutter outnumber girls who stutter by about a two to one ratio, or less.<ref name="fn 28"/> This ratio widens to three to one during first grade, and five to one during fifth grade,<ref>{{harvnb|Guitar|2005|p= 22}}</ref> as girls have higher recovery rates.<ref name="Ward16"/> <ref name="Yairi99">{{cite journal |author=Yairi, E. |author2=Ambrose, N. G. |title=Early childhood stuttering I: persistency and recovery rates |journal=Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research |volume=42 |issue=5 |pages=1097–112 |year=1999 |pmid=10515508 |doi=10.1044/jslhr.4205.1097}}</ref> the overall prevalence of stuttering is generally considered to be approximately 1%.<ref name="Craig">{{cite journal |author=Craig, A. |author2=Hancock, K. |author3=Tran, Y.; Craig, M. |author4=Peters, K. |title=Epidemiology of stuttering in the community across the entire life span |journal=Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research|volume=45 |issue=6 |pages=1097–105 |year=2002 |pmid=12546480 | doi = 10.1044/1092-4388(2002/088) }}</ref> | ||

| ===Cross cultural=== | ===Cross cultural=== | ||

| Cross-cultural studies of stuttering prevalence were very active in early and mid-20th century, particularly under the influence of the works of ], who claimed that the onset of stuttering was connected to the cultural expectations and the pressure put on young children by anxious parents |

Cross-cultural studies of stuttering prevalence were very active in early and mid-20th century, particularly under the influence of the works of ], who claimed that the onset of stuttering was connected to the cultural expectations and the pressure put on young children by anxious parents, which has since been debunked. Later studies found that this claim was not supported by the facts, so the influence of cultural factors in stuttering research declined. It is generally accepted by contemporary scholars that stuttering is present in every culture and in every race, although the attitude towards the actual prevalence differs. Some believe stuttering occurs in all cultures and races<ref name="Guitar5–6"/> at similar rates,<ref name="craig2005"/> about 1% of general population (and is about 5% among young children) all around the world. A US-based study indicated that there were no racial or ethnic differences in the incidence of stuttering in preschool children.<ref name="Proctor">{{cite journal|author= Proctor, A. |author2=Duff, M. |author3=Yairi, E. |year=2002|title=Early childhood stuttering: African Americans and European Americans|journal=ASHA Leader|volume=4|issue=15|page=102}}</ref><ref name="Yairi2005">{{cite journal|author= Yairi, E. |author2=Ambrose, N. |year=2005|title=Early childhood stuttering|journal=Pro-Ed}}</ref> | ||

| Different regions of the world are researched |

Different regions of the world are researched unevenly. The largest number of studies has been conducted in European countries and in North America, where the experts agree on the mean estimate to be about 1% of the general population (Bloodtein, 1995. A Handbook on Stuttering). African populations, particularly from West Africa, might have the highest stuttering prevalence in the world—reaching in some populations 5%, 6% and even over 9%.<ref>{{cite journal|author = Nwokah, E|year=1988|title=The imbalance of stuttering behavior in bilingual speakers|journal=Journal of Fluency Disorders|volume=13|pages=357–373|doi = 10.1016/0094-730X(88)90004-6|issue = 5}}</ref> Many regions of the world are not researched sufficiently, and for some major regions there are no prevalence studies at all.<ref name="reese">{{cite journal|author= Sheree Reese, ]|title= Stuttering in the Chinese population in some Southeast Asian countries: A preliminary investigation on attitude and incidence|journal= "Stuttering Awareness Day"; Minnesota State University, Mankato|year= 2001|url= http://www.mnsu.edu/comdis/isad4/papers/reese2.html|url-status= live|archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20110606033525/http://www.mnsu.edu/comdis/isad4/papers/reese2.html|archive-date= 2011-06-06}}</ref> | ||

| ==History== | ==History== | ||

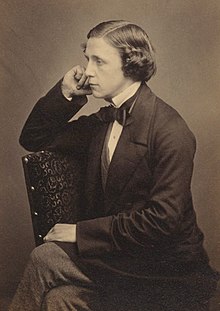

| ], the well-known author of'' ]'', had a stammer, as did his siblings.]] | ], the well-known author of'' ]'', had a stammer, as did his siblings.]] | ||

| Because of the unusual-sounding speech that is produced and the behaviors and attitudes that accompany a stutter, it has long been a subject of scientific interest and speculation as well as discrimination and ridicule. People who stutter can be traced back centuries to |

Because of the unusual-sounding speech that is produced and the behaviors and attitudes that accompany a stutter, it has long been a subject of scientific interest and speculation as well as discrimination and ridicule. People who stutter can be traced back centuries to ], who tried to control his disfluency by speaking with pebbles in his mouth.<ref name="brosch">{{cite journal |author=Brosch, S |author2=Pirsig, W. |title=Stuttering in history and culture |journal=Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. |volume=59 |issue=2 |pages=81–7 |year=2001 |pmid=11378182 | doi = 10.1016/S0165-5876(01)00474-8 }}</ref> The ] interprets ] passages to indicate that ] also stuttered, and that placing a burning coal in his mouth had caused him to be "slow and hesitant of speech" (Exodus 4, v.10).<ref name="brosch"/> | ||

| ]'s humoral theories were influential in Europe in the Middle Ages for centuries afterward. In this theory, stuttering was attributed to an imbalance of the ]—yellow bile, blood, black bile, and phlegm. ], writing in the sixteenth century, proposed to redress the imbalance by changes in diet, reduced libido (in men only), and ]. Believing that fear aggravated stuttering, he suggested techniques to overcome this. Humoral manipulation continued to be a dominant treatment for stuttering until the eighteenth century.<ref name="rieber">{{cite journal |author=Rieber, RW |author2=Wollock, J |title=The historical roots of the theory and therapy of stuttering |journal=Journal of Communication Disorders |volume=10 |issue=1–2 |pages=3–24 |year=1977 |pmid=325028 | doi = 10.1016/0021-9924(77)90009-0 }}</ref> Partly due to a perceived lack of intelligence because of his stutter, the man who became the ] ] was initially shunned from the public eye and excluded from public office.<ref name="brosch"/> | ]'s humoral theories were influential in Europe in the Middle Ages for centuries afterward. In this theory, stuttering was attributed to an imbalance of the ]—yellow bile, blood, black bile, and phlegm. ], writing in the sixteenth century, proposed to redress the imbalance by changes in diet, reduced libido (in men only), and ]. Believing that fear aggravated stuttering, he suggested techniques to overcome this. Humoral manipulation continued to be a dominant treatment for stuttering until the eighteenth century.<ref name="rieber">{{cite journal |author=Rieber, RW |author2=Wollock, J |title=The historical roots of the theory and therapy of stuttering |journal=Journal of Communication Disorders |volume=10 |issue=1–2 |pages=3–24 |year=1977 |pmid=325028 | doi = 10.1016/0021-9924(77)90009-0 }}</ref> Partly due to a perceived lack of intelligence because of his stutter, the man who became the ] ] was initially shunned from the public eye and excluded from public office.<ref name="brosch"/> | ||

| Line 189: | Line 183: | ||

| Some people who stutter, and are part of the ], have begun to embrace their stuttering voices as an important part of their identity.<ref>{{Cite web|title = Did I Stutter?|url = http://didistutter.org/|website = Did I Stutter?|access-date = 2015-10-05|url-status = live|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20151006092633/http://www.didistutter.org/|archive-date = 2015-10-06}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|title = How To Stutter More|url = http://stuttermore.tumblr.com/|website = stuttermore.tumblr.com|access-date = 2015-10-05|url-status = live|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20151029165325/http://stuttermore.tumblr.com/|archive-date = 2015-10-29}}</ref> In July 2015 the UK Ministry of Defence (MOD) announced the launch of the Defence Stammering Network to support and champion the interests of British military personnel and MOD civil servants who stammer and to raise awareness of the condition.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.gov.uk/government/news/defence-stammering-network-launched |title=Defence Stammering Network launched |access-date=2015-07-25 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150825135116/https://www.gov.uk/government/news/defence-stammering-network-launched |archive-date=2015-08-25 }}</ref> | Some people who stutter, and are part of the ], have begun to embrace their stuttering voices as an important part of their identity.<ref>{{Cite web|title = Did I Stutter?|url = http://didistutter.org/|website = Did I Stutter?|access-date = 2015-10-05|url-status = live|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20151006092633/http://www.didistutter.org/|archive-date = 2015-10-06}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|title = How To Stutter More|url = http://stuttermore.tumblr.com/|website = stuttermore.tumblr.com|access-date = 2015-10-05|url-status = live|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20151029165325/http://stuttermore.tumblr.com/|archive-date = 2015-10-29}}</ref> In July 2015 the UK Ministry of Defence (MOD) announced the launch of the Defence Stammering Network to support and champion the interests of British military personnel and MOD civil servants who stammer and to raise awareness of the condition.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.gov.uk/government/news/defence-stammering-network-launched |title=Defence Stammering Network launched |access-date=2015-07-25 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150825135116/https://www.gov.uk/government/news/defence-stammering-network-launched |archive-date=2015-08-25 }}</ref> | ||

| == Bilingual stuttering == | === Bilingual stuttering === | ||

| ⚫ | ==== Identification ==== | ||

| ⚫ | ] is the ability to speak two languages. Many bilingual people have been exposed to more than one language since birth and throughout childhood. Since language and culture are relatively fluid factors in a person's understanding and production of language, bilingualism may be a feature that impacts speech fluency. There are several ways during which stuttering may be noticed in bilingual children including the following. | ||

| ⚫ | === Identification === | ||

| ⚫ | Bilingualism is the ability to speak two languages. Many bilingual people have been exposed to more than one language since birth and throughout childhood. Since language and culture are relatively fluid factors in a person's understanding and production of language, bilingualism may be a feature that impacts speech fluency. There are several ways during which stuttering may be noticed in bilingual children including the following. | ||

| * The child is mixing vocabulary (code mixing) from both languages in one sentence. This is a normal process that helps the child increase their skills in the weaker language, but may trigger a temporary increase in disfluency.<ref name="Stuttering and the Bilingual Child">{{Cite web|url=https://www.stutteringhelp.org/stuttering-and-bilingual-child|title=Stuttering and the Bilingual Child|website=Stuttering Foundation: A Nonprofit Organization Helping Those Who Stutter|date=6 May 2011 |access-date=2017-12-18|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170926020934/http://www.stutteringhelp.org/stuttering-and-bilingual-child|archive-date=2017-09-26}}</ref> | * The child is mixing vocabulary (code mixing) from both languages in one sentence. This is a normal process that helps the child increase their skills in the weaker language, but may trigger a temporary increase in disfluency.<ref name="Stuttering and the Bilingual Child">{{Cite web|url=https://www.stutteringhelp.org/stuttering-and-bilingual-child|title=Stuttering and the Bilingual Child|website=Stuttering Foundation: A Nonprofit Organization Helping Those Who Stutter|date=6 May 2011 |access-date=2017-12-18|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170926020934/http://www.stutteringhelp.org/stuttering-and-bilingual-child|archive-date=2017-09-26}}</ref> | ||

| * The child is having difficulty finding the correct word to express ideas resulting in an increase in normal speech disfluency.<ref name="Stuttering and the Bilingual Child"/> | * The child is having difficulty finding the correct word to express ideas resulting in an increase in normal speech disfluency.<ref name="Stuttering and the Bilingual Child"/> | ||

| * The child is having difficulty using grammatically complex sentences in one or both languages as compared to other children of the same age. Also, the child may make grammatical mistakes. Developing proficiency in both languages may be gradual, so development may be uneven between the two languages.<ref name="Stuttering and the Bilingual Child"/> | * The child is having difficulty using grammatically complex sentences in one or both languages as compared to other children of the same age. Also, the child may make grammatical mistakes. Developing proficiency in both languages may be gradual, so development may be uneven between the two languages.<ref name="Stuttering and the Bilingual Child"/> | ||

| It was once believed that being bilingual would 'confuse' a child and cause stuttering, but research has debunked this myth. <ref>{{cite journal |last1=Kornisch |first1=Myriam |title=Bilinguals who stutter: A cognitive perspective |journal=Journal of Fluency Disorders |date=2020 Dec 3 |doi=10.1016/j.jfludis.2020.105819 |pmid=33296800 |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33296800/}}</ref> | |||

| Stuttering may present differently depending on the languages the individual uses. For example, morphological and other linguistic differences between languages may make presentation of disfluency appear to be more or less depending on the individual case.<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=aAbPBQAAQBAJ&q=bilingual+stuttering+wiki&pg=PA362|title=Multilingual Aspects of Fluency Disorders|last1=Howell|first1=Peter|last2=Borsel|first2=John Van|date=2011|publisher=Multilingual Matters|isbn=9781847693587}}</ref> | Stuttering may present differently depending on the languages the individual uses. For example, morphological and other linguistic differences between languages may make presentation of disfluency appear to be more or less depending on the individual case.<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=aAbPBQAAQBAJ&q=bilingual+stuttering+wiki&pg=PA362|title=Multilingual Aspects of Fluency Disorders|last1=Howell|first1=Peter|last2=Borsel|first2=John Van|date=2011|publisher=Multilingual Matters|isbn=9781847693587}}</ref> | ||

| Line 265: | Line 262: | ||

| ==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| {{Reflist}} | {{Reflist}} | ||

| ==References== | |||

| * {{Cite book | last =Guitar | first =Barry | title =Stuttering: An Integrated Approach to Its Nature and Treatment | publisher =] | year =2005 | location =] | isbn = 978-0-7817-3920-7 }} | |||

| * {{Cite book | last =Ward | first =David | title =Stuttering and Cluttering: Frameworks for understanding treatment | publisher =Psychology Press | year =2006 | location =] and ] | isbn =978-1-84169-334-7 }}<references group="National Stuttering Foundation"/> | |||

| ==Further reading== | ==Further reading== | ||

| *{{cite journal |author=Alm, Per A |title=Stuttering and the basal ganglia circuits: a critical review of possible relations |journal=Journal of Communication Disorders |volume=37 |issue=4 |pages=325–69 |year=2004 |pmid=15159193 |url=http://theses.lub.lu.se/scripta-archive/2005/02/02/med_1035/part2/Per_Alm_Paper_II.pdf |doi=10.1016/j.jcomdis.2004.03.001 }}{{dead link|date=March 2018 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }} | |||

| * Alm, Per A. (2005). ''''. Doctoral dissertation, Dept. of Clinical Neuroscience, ], Sweden. | |||

| * {{cite book | author=Compton DG | title=Stammering : its nature, history, causes and cures | publisher=Hodder & Stoughton | year=1993 | isbn=978-0-340-56274-1}} | |||

| * {{cite book | author=Conture, Edward G | title=Stuttering | publisher=Prentice Hall | year=1990 | isbn=978-0-13-853631-2}} | |||

| * {{cite book | author=Fraser, Jane | title=If Your Child Stutters: A Guide for Parents | publisher=Stuttering Foundation of America | year=2005 | isbn=978-0-933388-44-4 | url-access=registration | url=https://archive.org/details/ifyourchildstutt00ains }} | |||

| * Mondlin, M., ''How My Stuttering Ended'' http://www.mnsu.edu/comdis/kuster/casestudy/path/mondlin.html | |||

| * {{cite book |author=Raz, Mirla G. | title=Preschool Stuttering: What Parents Can Do | publisher=GerstenWeitz Publishers| year=2014 | isbn=9780963542625}} | |||

| * Rockey, D., ''Speech Disorder in Nineteenth Century Britain: The History of Stuttering'', Croom Helm, (London), 1980. {{ISBN|0-85664-809-4}} | * Rockey, D., ''Speech Disorder in Nineteenth Century Britain: The History of Stuttering'', Croom Helm, (London), 1980. {{ISBN|0-85664-809-4}} | ||

| * Goldmark, Daniel. "Stuttering in American Popular Song, 1890–1930." In {{cite book|last=Lerner|first=Neil|title=Sounding Off: Theorizing Disability in Music|year=2006|publisher=Routledge|location=New York, London|isbn=978-0-415-97906-1|pages=91–105}} | * Goldmark, Daniel. "Stuttering in American Popular Song, 1890–1930." In {{cite book|last=Lerner|first=Neil|title=Sounding Off: Theorizing Disability in Music|year=2006|publisher=Routledge|location=New York, London|isbn=978-0-415-97906-1|pages=91–105}} | ||

| * {{Cite book| |

* {{Cite book | last =Ward | first =David | title =Stuttering and Cluttering: Frameworks for understanding treatment | publisher =Psychology Press | year =2006 | location =] and ] | isbn =978-1-84169-334-7 }} | ||

| == External links == | == External links == | ||

| Line 286: | Line 272: | ||

| {{Wiktionary|stammering|stuttering}} | {{Wiktionary|stammering|stuttering}} | ||

| * | * | ||

| * {{Webarchive|url=http://arquivo.pt/wayback/20091016041011/http://www.asha.org/public/speech/disorders/stuttering.htm |date=2009-10-16 }} | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| *{{curlie|Health/Conditions_and_Diseases/Communication_Disorders/Language_and_Speech/Stuttering/Organizations/}} | |||

| {{Medical resources | {{Medical resources | ||

| Line 306: | Line 288: | ||

| {{Stuttering}} | {{Stuttering}} | ||

| {{Emotional and behavioral disorders}} | {{Emotional and behavioral disorders}} | ||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

Revision as of 23:35, 6 February 2024

Speech disorder "Stutter", "Stammer", "Stammerer", and "Stutterer" redirect here. For other uses of "Stutter", see Stutter (disambiguation). For other uses of "Stammer", see Stammer (disambiguation). For people with the epithet "the Stammerer", see List of people known as the Stammerer. For the film, see Stutterer (film). Medical condition| Stuttering | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Stammering, alalia syllabaris, alalia literalis, anarthria literalis, dysphemia. |

| Specialty | Speech–language pathology |

| Symptoms | Involuntary sound repetition and disruption or blocking of speech |

| Usual onset | 2–5 years |

| Duration | Long term |

| Causes | Unknown |

| Differential diagnosis | Dysphonia |

| Treatment | Speech therapy, Support |

| Medication | Dopamine antagonists |

| Prognosis | 80% developmental resolves by late childhood; 20% of cases last into adulthood |

| Frequency | About 1% |

Stuttering, also known as stammering, is a speech disorder in which the flow of speech is disrupted by involuntary repetitions and prolongations of sounds, syllables, words, or phrases as well as involuntary silent pauses or blocks in which the person who stutters is unable to produce sounds. The term stuttering is most commonly associated with involuntary sound repetition, but it also encompasses the abnormal hesitation or pausing before speech, referred to by people who stutter as blocks, and the prolongation of certain sounds, usually vowels or semivowels. According to Watkins et al., stuttering is a disorder of "selection, initiation, and execution of motor sequences necessary for fluent speech production". For many people who stutter, repetition is the main concern. The term "stuttering" covers a wide range of severity, from barely perceptible impediments that are largely cosmetic to severe symptoms that effectively prevent oral communication. Almost 70 million people worldwide stutter, about 1% of the world's population.

The impact of discrimination against stuttering on a dysfluent person's functioning and emotional state can be severe. This may include fears of having to enunciate specific vowels or consonants, fears of being caught stuttering in social situations, self-imposed isolation, anxiety, stress, shame, low self-esteem, being a possible target of bullying (especially in children), having to use word substitution and rearrange words in a sentence to hide stuttering, or a feeling of "loss of control" during speech. Stuttering is sometimes popularly seen as a symptom of anxiety, but there is no direct correlation in that direction.

Stuttering is generally not a problem with the physical production of speech sounds or putting thoughts into words. Acute nervousness and stress are not thought to cause stuttering, but they can trigger stuttering in people who have the speech disorder, and living with a stigmatized disability can result in anxiety and high allostatic stress load (chronic nervousness and stress) that increase the amount of acute stress necessary to trigger stuttering in any given person who stutters, worsening the situation in the manner of a positive feedback system; the name 'stuttered speech syndrome' has been proposed for this condition. Neither acute nor chronic stress, however, itself creates any predisposition to stuttering.

The disorder is also variable, which means that in certain situations, such as talking on the telephone or in a large group, the stuttering might be more noticable. People who stutter often find that their stuttering fluctuates. The times in which their stuttering fluctuates can be random. Although the exact etiology, or cause, of stuttering is unknown, both genetics and neurophysiology are shown to contribute. There is no cure for the disorder.

Characteristics

Common behaviors

Common stuttering behaviors are observable signs of speech disfluencies, for example: repeating sounds, syllables, words or phrases, silent blocks and prolongation of sounds. These differ from the normal disfluencies found in all speakers in that stuttering disfluencies may last longer, occur more frequently, and are produced with more effort and strain.

- Repeated movements

- Syllable repetition—a single syllable word is repeated (for example: on—on—on a chair) or a part of a word which is still a full syllable such as "un—un—under the ..." and "o—o—open".

- Incomplete syllable repetition—an incomplete syllable is repeated, such as a consonant without a vowel, for example, "c—c—c—cold".

- Multi-syllable repetition—more than one syllable such as a whole word, or more than one word is repeated, such as "I know—I know—I know a lot of information."

- Fixed postures

- With audible airflow—prolongation of a sound occurs such as "mmmmmmmmmom".

- Without audible airflow—such as a block of speech or a tense pause where nothing is said despite efforts.

- Superfluous behaviors

- Verbal—this includes an interjection such as an unnecessary uh or um as well as revisions, such as going back and correcting one's initial statements such as "I—My girlfriend ...", where the I has been corrected to the word my.

- Nonverbal—these are visible or audible speech behaviors, such as lip smacking, throat clearing, head thrusting, etc., usually representing an effort to break through or circumvent a block or stuttering loop.

Feelings and attitudes

Stuttering could have a significant negative cognitive and affective impact on the person who stutters. It has been described in terms of the analogy to an iceberg, with the immediately visible and audible symptoms of stuttering above the waterline and a broader set of symptoms such as negative emotions hidden below the surface. Feelings of embarrassment, shame, frustration, fear, anger, and guilt are frequent in people who stutter, and may actually increase tension and effort, leading to increased stuttering. With time, continued exposure to difficult speaking experiences may crystallize into a negative self-concept and self-image. People who stutter may project their attitudes onto others, believing that the others think them nervous or stupid. Such negative feelings and attitudes may need to be a major focus of a treatment program.

Many people who stutter report a high emotional cost, including jobs or promotions not received, as well as relationships broken or not pursued.

Others have developed Stuttering pride and encourage other stutterers to take pride in their stutter and to find how it has been beneficial for them.

Associated conditions

Stuttering can co-occur with other learning disorders. These associated disabilities include:

- Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): A disorder characterized by problems sustaining attention, hyperactivity, or acting impulsively. The prevalence of ADHD in school-aged children who stutter is around 4-50%.

- Dyslexia: A disorder involving difficulties with reading and spelling. The prevalence rate of childhood stuttering in dyslexia is around 30-40%, while in adults the prevalence of dyslexia in adults who stutter is around 30-50%.

- autism spectrum disorder

- intellectual disability

- language or learning disability

- seizure disorders

- social anxiety disorder

- speech sound disorders

- other developmental disorders

Causes

The cause of developmental stuttering is complex and thought to be neurological with a genetic factor.

A variety of hypotheses and theories suggest multiple factors contributing to stuttering. There is strong evidence that stuttering has a genetic basis. Children who have first-degree relatives who stutter are three times as likely to develop a stutter. However, twin and adoption studies suggest that genetic factors interact with environmental factors for stuttering to occur, and many stutterers have no family history of the disorder. In a 2010 article, three genes were found by Dennis Drayna and team to correlate with stuttering: GNPTAB, GNPTG, and NAGPA. Researchers estimated that alterations in these three genes were present in 9% of those who have a family history of stuttering.

There is evidence that stuttering is more common in children who also have concurrent speech, language, learning or motor difficulties. For some people who stutter, congenital factors may play a role. These may include physical trauma at or around birth, learning disabilities, and cerebral palsy. In others, there could be added impact due to stressful situations such as the birth of a sibling, moving, or a sudden growth in linguistic ability.

There is empirical evidence for structural and functional differences in the brains of stutterers. Research is complicated somewhat by the possibility that such differences could be the consequences of stuttering rather than a cause, but recent research on older children confirms structural differences thereby giving strength to the argument that at least some of the differences are not a consequence of stuttering.

Other much less common causes of stuttering include neurogenic stuttering (stuttering that occurs secondary to brain damage, such as after a stroke) and psychogenic stuttering (stuttering related to a psychological condition).

History of Causes

Auditory processing deficits have also been proposed as a cause of stuttering. Stuttering is less prevalent in deaf and hard-of-hearing individuals, and stuttering may be reduced when auditory feedback is altered, such as by masking, delayed auditory feedback (DAF), or frequency altered feedback. There is some evidence that the functional organization of the auditory cortex may be different in people who stutter.

There is evidence of differences in linguistic processing between people who stutter and people who do not. Brain scans of adult stutterers have found greater activation of the right hemisphere, which is associated with emotions, than of the left hemisphere, which is associated with speech. In addition, reduced activation in the left auditory cortex has been observed.

The capacities and demands model has been proposed to account for the heterogeneity of the disorder. In this approach, speech performance varies depending on the capacity that the individual has for producing fluent speech, and the demands placed upon the person by the speaking situation. Capacity for fluent speech may be affected by a predisposition to the disorder, auditory processing or motor speech deficits, and cognitive or affective issues. Demands may be increased by internal factors such as lack of confidence or self esteem or inadequate language skills or external factors such as peer pressure, time pressure, stressful speaking situations, insistence on perfect speech, and the like. In stuttering, the severity of the disorder is seen as likely to increase when demands placed on the person's speech and language system exceed their capacity to deal with these pressures. However, the precise nature of the capacity or incapacity has not been delineated.

Main article: Dopamine hypothesis of stutteringOne theory studies have found that adults who stutter have elevated levels of the neurotransmitter dopamine, and have thus found dopamine antagonists that reduce stuttering. Overactivity of the midbrain has been found at the level of the substantia nigra extended to the red nucleus and subthalamic nucleus, which all contribute to the production of dopamine. However, increased dopamine does not imply increased excitatory function since dopamine's effect can be both excitatory or inhibitory depending upon which dopamine receptors have been stimulated.

Diagnosis

Some characteristics of stuttered speech are not as easy for listeners to detect. As a result, diagnosing stuttering requires the skills of a certified speech–language pathologist (SLP). Diagnosis of stuttering employs information both from direct observation of the individual and information about the individual's background, through a case history. Information from both sources should consider things such as age, the various times it has occurred, and other impediments. The SLP may collect a case history on the individual through a detailed interview or conversation with the parents (if client is a child). They may also observe parent-child interactions and observe the speech patterns of the child's parents. The overall goal of assessment for the SLP will be (1) to determine whether a speech disfluency exists, and (2) assess if its severity warrants concern for further treatment.

During direct observation of the client, the SLP will observe various aspects of the individual's speech behaviors. In particular, the therapist might test for factors including the types of disfluencies present (using a test such as the Disfluency Type Index (DTI)), their frequency and duration (number of iterations, percentage of syllables stuttered (%SS)), and speaking rate (syllables per minute (SPM), words per minute (WPM)). They may also test for naturalness and fluency in speaking (naturalness rating scale (NAT), test of childhood stuttering (TOCS)) and physical concomitants during speech (Riley's Stuttering Severity Instrument Fourth Edition (SSI-4)). They might also employ a test to evaluate the severity of the stuttering and predictions for its course. One such test includes the stuttering prediction instrument for young children (SPI), which analyzes the child's case history, part-word repetitions and prolongations, and stuttering frequency in order to determine the severity of the disfluency and its prognosis for chronicity for the future.

Stuttering is a multifaceted, complex disorder that can impact an individual's life in a variety of ways. Children and adults are monitored and evaluated for evidence of possible social, psychological or emotional signs of stress related to their disorder. Some common assessments of this type measure factors including: anxiety (Endler multidimensional anxiety scales (EMAS)), attitudes (personal report of communication apprehension (PRCA)), perceptions of self (self-rating of reactions to speech situations (SSRSS)), quality of life (overall assessment of the speaker's experience of stuttering (OASES)), behaviors (older adult self-report (OASR)), and mental health (composite international diagnostic interview (CIDI)).

Clinical psychologists with adequate expertise can also diagnose Stuttering per the DSM-5 diagnostic codes. The DSM-5 describes Childhood-Onset Fluency Disorder (Stuttering)" for developmental stuttering, and "Adult-onset Fluency Disorder". However, the specific rationale for this change from the DSM-IV is ill-documented in the APA's published literature, and is felt by some to promote confusion between the very different terms "fluency" and "disfluency".

Normal disfluency

Main article: Developmental dysfluencyPreschool aged children often have difficulties with speech concerning motor planning and execution; this often manifests as disfluencies related to speech development (referred to as normal dysfluency or "other disfluencies"). This type of disfluency is a normal part of speech development and temporarily present in preschool aged children who are learning to speak.

Classification

Developmental stuttering is stuttering that originates when a child is learning to speak and may persist as the child matures into adulthood. Stuttering that persists after the age of seven is classified as persistent stuttering.

Neurogenic stuttering (stuttering that occurs secondary to brain damage, such as after a stroke) and psychogenic stuttering (stuttering related to a psychological condition) are less common and classified separately from developmental.

Developmental

Stuttering usually begins in early childhood. The mean onset of stuttering is 30 months. With young stutterers, disfluency may be episodic, and periods of stuttering are followed by periods of relatively decreased disfluency.

With time a young person who stutters might transition from easy, relaxed repetition to more tense and effortful stuttering, including blocks and prolongations. Some propose that parental reactions may affect this development. With time, secondary stuttering, including escape behaviours such as eye blinking and lip movements, may be used, as well as fear and avoidance of sounds, words, people, or speaking situations. Eventually, some become fully aware of their disorder and begin to identify themselves as stutterers. Depending on the situation, this may come with deeper frustration, embarrassment and shame.

Other patterns of stuttering development have been described, including sudden onset, with the child being unable to speak, despite attempts to do so. The child usually is unable to utter the first sound of a sentence, and shows high levels of awareness and frustration. Another variety also begins suddenly with frequent word and phrase repetition, and does not include the development of secondary stuttering behaviours

Neurogenic stuttering

Some stuttering is also believed to be caused by neurophysiology. Neurogenic stuttering typically appears following some sort of injury or disease to the central nervous system. Injuries to the brain and spinal cord, including cortex, subcortex, cerebellum, and even the neural pathway regions.

Acquired stuttering

In rare cases, stuttering may be acquired in adulthood as the result of a neurological event such as a head injury, tumour, stroke, or drug use. This stuttering has different characteristics from its developmental equivalent: it tends to be limited to part-word or sound repetitions, and is associated with a relative lack of anxiety and secondary stuttering behaviors. Techniques such as altered auditory feedback are not effective with the acquired type.

Even more rare, psychogenic stuttering may also arise after a traumatic experience such as a death, the breakup of a relationship or as the psychological reaction to physical trauma. Its symptoms tend to be homogeneous: the stuttering is of sudden onset and associated with a significant event, it is constant and uninfluenced by different speaking situations, and there is little awareness or concern shown by the speaker.

Differential diagnosis

Other disorders with symptoms resembling stuttering, or associated disorders include autism, cluttering, Parkinson's disease, essential tremor, palilalia, spasmodic dysphonia, and selective mutism.

Treatment

Main article: Stuttering therapyWhile there is no cure for stuttering, several treatment options exist and the best option is dependent on the individual.

Depending the child or adult, therapy is generally a management of speech comfort, and/or teaching techniques to speak in a controlled way.

Fluency shaping therapy

Fluency shaping therapy trains people who stutter to speak less disfluently by controlling their breathing, phonation, and articulation (lips, jaw, and tongue). It is based on operant conditioning techniques.

Modification therapy

The goal of stuttering modification therapy is not to eliminate stuttering but to modify it so that stuttering is easier and less effortful. The most widely known approach was published by Charles Van Riper in 1973 and is also known as block modification therapy. However, depending on the patient, speech therapy may be ineffective.

Electronic fluency device

Main article: Electronic fluency deviceAltered auditory feedback effect can be produced by speaking in chorus with another person, by blocking out the voice of the person who stutters while they are talking (masking), by delaying slightly the voice of the person who stutters (delayed auditory feedback) or by altering the frequency of the feedback (frequency altered feedback). Studies of these techniques have had mixed results.

Medications

No medication is FDA-approved for stuttering.

Support

Self-help groups provide people who stutter a shared forum within which they can access resources and support from others facing the same challenges of stuttering.

Prognosis

Among preschoolers with stuttering, the prognosis for recovery is about 65% to 87.5% of preschoolers who stutter recover spontaneously by 7 years of age or within the first 2 years of stuttering, and about 74% recover by their early teens. In particular, girls seem to recover more often.

Prognosis is guarded with later age of onset: children who start stuttering at age 3½ years or later, and/or duration of greater than 6–12 months since onset, that is, once stuttering has become established, about 18% of children who stutter after five years recover spontaneously. Stuttering that persists after the age of seven is classified as persistent stuttering, and is associated with a much lower chance of recovery.

Epidemiology

The lifetime prevalence, or the proportion of individuals expected to stutter at one time in their lives, is about 5%, and overall males are affected two to five times more often than females.As seen in children who have just begun stuttering, there is an equivalent number of boys and girls who stutter. Still, the sex ratio appears to widen as children grow: among preschoolers, boys who stutter outnumber girls who stutter by about a two to one ratio, or less. This ratio widens to three to one during first grade, and five to one during fifth grade, as girls have higher recovery rates. the overall prevalence of stuttering is generally considered to be approximately 1%.

Cross cultural

Cross-cultural studies of stuttering prevalence were very active in early and mid-20th century, particularly under the influence of the works of Wendell Johnson, who claimed that the onset of stuttering was connected to the cultural expectations and the pressure put on young children by anxious parents, which has since been debunked. Later studies found that this claim was not supported by the facts, so the influence of cultural factors in stuttering research declined. It is generally accepted by contemporary scholars that stuttering is present in every culture and in every race, although the attitude towards the actual prevalence differs. Some believe stuttering occurs in all cultures and races at similar rates, about 1% of general population (and is about 5% among young children) all around the world. A US-based study indicated that there were no racial or ethnic differences in the incidence of stuttering in preschool children.

Different regions of the world are researched unevenly. The largest number of studies has been conducted in European countries and in North America, where the experts agree on the mean estimate to be about 1% of the general population (Bloodtein, 1995. A Handbook on Stuttering). African populations, particularly from West Africa, might have the highest stuttering prevalence in the world—reaching in some populations 5%, 6% and even over 9%. Many regions of the world are not researched sufficiently, and for some major regions there are no prevalence studies at all.

History

Because of the unusual-sounding speech that is produced and the behaviors and attitudes that accompany a stutter, it has long been a subject of scientific interest and speculation as well as discrimination and ridicule. People who stutter can be traced back centuries to Demosthenes, who tried to control his disfluency by speaking with pebbles in his mouth. The Talmud interprets Bible passages to indicate that Moses also stuttered, and that placing a burning coal in his mouth had caused him to be "slow and hesitant of speech" (Exodus 4, v.10).

Galen's humoral theories were influential in Europe in the Middle Ages for centuries afterward. In this theory, stuttering was attributed to an imbalance of the four bodily humors—yellow bile, blood, black bile, and phlegm. Hieronymus Mercurialis, writing in the sixteenth century, proposed to redress the imbalance by changes in diet, reduced libido (in men only), and purging. Believing that fear aggravated stuttering, he suggested techniques to overcome this. Humoral manipulation continued to be a dominant treatment for stuttering until the eighteenth century. Partly due to a perceived lack of intelligence because of his stutter, the man who became the Roman emperor Claudius was initially shunned from the public eye and excluded from public office.

In and around eighteenth and nineteenth century Europe, surgical interventions for stuttering were recommended, including cutting the tongue with scissors, removing a triangular wedge from the posterior tongue, and cutting nerves, or neck and lip muscles. Others recommended shortening the uvula or removing the tonsils. All were abandoned due to the danger of bleeding to death and their failure to stop stuttering. Less drastically, Jean Marc Gaspard Itard placed a small forked golden plate under the tongue in order to support "weak" muscles.

Italian pathologist Giovanni Morgagni attributed stuttering to deviations in the hyoid bone, a conclusion he came to via autopsy. Blessed Notker of St. Gall (c. 840 – 912), called Balbulus ("The Stutterer") and described by his biographer as being "delicate of body but not of mind, stuttering of tongue but not of intellect, pushing boldly forward in things Divine," was invoked against stammering.

A royal Briton who stammered was King George VI. He went through years of speech therapy, most successfully under Australian speech therapist Lionel Logue, for his stammer. The Academy Award-winning film The King's Speech (2010) in which Colin Firth plays George VI, tells his story. The film is based on an original screenplay by David Seidler, who also stuttered until age 16.

Another British case was that of Prime Minister Winston Churchill. Churchill claimed, perhaps not directly discussing himself, that "ometimes a slight and not unpleasing stammer or impediment has been of some assistance in securing the attention of the audience ..." However, those who knew Churchill and commented on his stutter believed that it was or had been a significant problem for him. His secretary Phyllis Moir commented that "Winston Churchill was born and grew up with a stutter" in her 1941 book I was Winston Churchill's Private Secretary. She related one example, "'It's s-s-simply s-s-splendid,' he stuttered—as he always did when excited." Louis J. Alber, who helped to arrange a lecture tour of the United States, wrote in Volume 55 of The American Mercury (1942) that "Churchill struggled to express his feelings but his stutter caught him in the throat and his face turned purple" and that "born with a stutter and a lisp, both caused in large measure by a defect in his palate, Churchill was at first seriously hampered in his public speaking. It is characteristic of the man's perseverance that, despite his staggering handicap, he made himself one of the greatest orators of our time."

For centuries "cures" such as consistently drinking water from a snail shell for the rest of one's life, "hitting a stutterer in the face when the weather is cloudy", strengthening the tongue as a muscle, and various herbal remedies were tried. Similarly, in the past people subscribed to odd theories about the causes of stuttering, such as tickling an infant too much, eating improperly during breastfeeding, allowing an infant to look in the mirror, cutting a child's hair before the child spoke his or her first words, having too small a tongue, or the "work of the devil".

Some people who stutter, and are part of the disability rights movement, have begun to embrace their stuttering voices as an important part of their identity. In July 2015 the UK Ministry of Defence (MOD) announced the launch of the Defence Stammering Network to support and champion the interests of British military personnel and MOD civil servants who stammer and to raise awareness of the condition.

Bilingual stuttering

Identification

Bilingualism is the ability to speak two languages. Many bilingual people have been exposed to more than one language since birth and throughout childhood. Since language and culture are relatively fluid factors in a person's understanding and production of language, bilingualism may be a feature that impacts speech fluency. There are several ways during which stuttering may be noticed in bilingual children including the following.

- The child is mixing vocabulary (code mixing) from both languages in one sentence. This is a normal process that helps the child increase their skills in the weaker language, but may trigger a temporary increase in disfluency.

- The child is having difficulty finding the correct word to express ideas resulting in an increase in normal speech disfluency.

- The child is having difficulty using grammatically complex sentences in one or both languages as compared to other children of the same age. Also, the child may make grammatical mistakes. Developing proficiency in both languages may be gradual, so development may be uneven between the two languages.

It was once believed that being bilingual would 'confuse' a child and cause stuttering, but research has debunked this myth.

Stuttering may present differently depending on the languages the individual uses. For example, morphological and other linguistic differences between languages may make presentation of disfluency appear to be more or less depending on the individual case.

In popular culture

See also: Stuttering in popular cultureJazz and Eurodance musician Scatman John wrote the song "Scatman (Ski Ba Bop Ba Dop Bop)" to help children who stutter overcome adversity. Born John Paul Larkin, Scatman spoke with a stutter himself and won the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association's Annie Glenn Award for outstanding service to the stuttering community.

Arkwright, the main protagonist in the BBC sitcom Open All Hours, had a severe stutter that was used for comic effect. Laxman, a supporting character in Indian comedy film Golmaal (2010), had stammering problem.

Stuttering Community

Many counties have regular events and activities to get people who stutter together in mutual support. These events take place at regional, national, and international level. At a regional level, there are often stuttering support or chapter groups that look to provide a place for people who stutter in the local area to meet, discuss and learn from each other.

At a national level, stuttering charities or groups host conferences. Conferences can vary in their focus and scope, some focus on the latest research developments, some on stuttering and the arts and others still look to provide a space for stutterers simply to come together.

There are two different international meetings of stutterers. The International Stuttering Association World Congress is primarily focused on people who stutter. There is also Joint World Congress on Stuttering and Cluttering that brings together academics, researchers, speech-language pathologists, people who stutter, and people who clutter for a focus more on research, viewpoints, and treatments for stuttering.

Historic advocacy and self-help

Self-help and advocacy organisations for people who stammer have reportedly been in existence since the 1920s. In 1921, a Philadelphia-based attorney who stammered, J Stanley Smith established the Kingsley Club. Designed to support people with a stammer in the Philadelphia area the club took inspiration for its name from Charles Kingsley. Kingsley, a nineteenth century English social reformer and author of Westward Ho! and The Water Babies had a stammer himself.

Whilst Kingsley himself did not appear to recommend self-help or advocacy groups for people who stammer the Kingsley Club promoted a positive mental attitude to support its members in becoming confident speakers, in a similar way discussed by Charles Kingsley in Irrationale of Speech.

Other support groups for people who stammer began to emerge in the first half of the twentieth century. In 1935 a Stammerer’s Club was established in Melbourne, Australia by a Mr H Collin of Thornbury. At the time of its formation it had 68 members. The club was formed in response to the tragic case of a man from Sydney who “sought relief from the effects of stammering in suicide”. As well as providing self-help this club adopted an advocacy role with the intention of appealing to the Government to provide special education and to fund research into the causes of stammering (Bermuda Reporter).

Stuttering Pride

Stuttering pride (or stuttering advocacy) is a social movement repositioning stuttering as a valuable and respectable way of speaking. The movement seeks to counter the societal narratives in which temporal and societal expectations dictate how communication takes place. In this sense, the stuttering pride movement challenges the pervasive societal narrative of stuttering as a defect and instead positions stuttering as a valuable and respectable way of speaking in its own right. The movement encourages stutterers to take pride in their unique speech patterns and in what stuttering can tell us about the world. It also advocates for societal adjustments to allow stutterers equal access to education and employment opportunities, and addresses how this may impact Stuttering therapy.

Associations

- All India Institute of Speech and Hearing

- American Institute for Stuttering

- British Stammering Association

- European League of Stuttering Associations

- International Stuttering Association

- Israel Stuttering Association

- Michael Palin Centre for Stammering Children

- National Stuttering Association, United States

- Philippine Stuttering Association

- Stuttering Foundation of America

- The Indian Stammering Association

See also

- American Speech–Language–Hearing Association

- Cluttering

- Developmental dysfluency

- Dopamine hypothesis of stuttering

- Dyscravia

- Fluency

- International Stuttering Awareness Day

- Lists of language disorders

- List of stutterers

- Monster Study

- National Stuttering Awareness Week

- Neurodevelopmental disorder

- Speech and language impairment

- Speech disorder

- Speech disfluency

- Speech–language pathology

- Speech processing

- Stuttering in popular culture

- Stuttering therapy

Notes

- ^ GREENE, J. S. (1937-07-01). "Dysphemia and Dysphonia: Cardinal Features of Three Types of Functional Syndrome: Stuttering, Aphonia and Falsetto (Male)". Archives of Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery. 26 (1). American Medical Association (AMA): 74–82. doi:10.1001/archotol.1937.00650020080011. ISSN 0886-4470.

- World Health Organization ICD-10 F95.8 – Stuttering Archived 2014-11-02 at the Wayback Machine.

- Sheikh, Shakeel; Sahidullah, Md; Hirsch, Fabrice; Ouni, Slim (July 2021). "Machine Learning for Stuttering Identification: Review, Challenges & Future Directions". arXiv:2107.04057 .

- ^

- "11 Facts About Stuttering". Archived from the original on 19 July 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- "What is the relationship between stuttering and anxiety? | British Stammering Association". www.stammering.org. Archived from the original on 2017-04-23. Retrieved 2019-03-20.

- Constantino CD, Campbell P, Simpson S (March–April 2022). "Stuttering and the social model". Journal of Communication Disorders. 96: 106200. doi:10.1016/j.jcomdis.2022.106200. ISSN 0021-9924. PMID 35248920. S2CID 247096437.

- http://www.stutteredspeechsyndrome.com Archived 2011-02-08 at the Wayback Machine

- Irwin, M. (2006). Au-Yeung, J.; Leahy, M. M. (eds.). Terminology – How should stuttering be defined? And why? – Research, Treatment, and Self-Help in Fluency Disorders: New Horizons. The International Fluency Association. pp. 41–45. ISBN 978-0-9555700-1-8. Archived from the original on 2015-09-28.

- Bowen, Caroline. "Information for Families: Stuttering- What can be done about it?". speech-language-therapy dot com. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved June 19, 2013.

- Ashurst JV, Wasson MN (October 2011). "Developmental and persistent developmental stuttering: an overview for primary care physicians". The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association. 111 (10): 576–80. PMID 22065298.

- Ward 2006, pp. 5–6

- Kalinowski & Saltuklaroglu 2006, p. 17 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFKalinowskiSaltuklaroglu2006 (help)

- Ward 2006, p. 179

- ^ Guitar 2005, pp. 16–7 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFGuitar2005 (help)

- Pollack, Andrew. "To Fight Stuttering, Doctors Look at the Brain Archived 2016-11-09 at the Wayback Machine", New York Times, September 12, 2006.

- Sroubek, Ariane; Kelly, Mary; Li, Xiaobo (2013-02-01). "Inattentiveness in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder". Neuroscience Bulletin. 29 (1): 103–110. doi:10.1007/s12264-012-1295-6. ISSN 1995-8218. PMC 4440572. PMID 23299717.

- Druker, Kerianne; Hennessey, Neville; Mazzucchelli, Trevor; Beilby, Janet (2019-03-01). "Elevated attention deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms in children who stutter". Journal of Fluency Disorders. 59: 80–90. doi:10.1016/j.jfludis.2018.11.002. ISSN 0094-730X. PMID 30477807. S2CID 53733731.

- Donaher, Joseph; Richels, Corrin (2012-12-01). "Traits of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in school-age children who stutter". Journal of Fluency Disorders. Special Issue: 9th Oxford Dysfluency Conference. 37 (4): 242–252. doi:10.1016/j.jfludis.2012.08.002. ISSN 0094-730X. PMID 23218208.

- Arndt Jennifer; Healey E. Charles (2001-04-01). "Concomitant Disorders in School-Age Children Who Stutter". Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools. 32 (2): 68–78. doi:10.1044/0161-1461(2001/006). PMID 27764357.

- Riley Jeanna; Riley Johnetta G. (2000-10-01). "A Revised Component Model for diagnosing and Treating Children Who Stutter". Contemporary Issues in Communication Science and Disorders. 27 (Fall): 188–199. doi:10.1044/cicsd_27_F_188.

- Peterson, Robin L; Pennington, Bruce F (May 2012). "Developmental dyslexia". The Lancet. 379 (9830): 1997–2007. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(12)60198-6. ISSN 0140-6736. PMC 3465717. PMID 22513218.

- Blood, Gordon W; Ridenour, Victor J; Qualls, Constance Dean; Hammer, Carol Scheffner (November 2003). "Co-occurring disorders in children who stutter". Journal of Communication Disorders. 36 (6): 427–448. doi:10.1016/S0021-9924(03)00023-6. PMID 12967738.

- Arndt, Jennifer; Healey, E. Charles (April 2001). "Concomitant Disorders in School-Age Children Who Stutter". Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools. 32 (2): 68–78. doi:10.1044/0161-1461(2001/006). ISSN 0161-1461. PMID 27764357.

- Elsherif, Mahmoud M.; Wheeldon, Linda R.; Frisson, Steven (2021-03-01). "Do dyslexia and stuttering share a processing deficit?". Journal of Fluency Disorders. 67: 105827. doi:10.1016/j.jfludis.2020.105827. ISSN 0094-730X. PMID 33444937. S2CID 231611179.

- ^ Briley, Patrick M.; Ellis, Charles (2018-12-10). "The Coexistence of Disabling Conditions in Children Who Stutter: Evidence From the National Health Interview Survey". Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 61 (12): 2895–2905. doi:10.1044/2018_JSLHR-S-17-0378. ISSN 1092-4388. PMID 30458520. S2CID 53946065.

- Healey, E. C., Reid, R., & Donaher, J. (2005). Treatment of the child who stutters with co-existing learning, behavioral, and cognitive challenges. In R. Lees & C. Stark (Eds.), The treatment of stuttering in the young school-aged child (pp. 178–196). Whurr Publishers.

- Ntourou, Katerina; Conture, Edward G.; Lipsey, Mark W. (August 2011). "Language Abilities of Children Who Stutter: A Meta-Analytical Review". American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 20 (3): 163–179. doi:10.1044/1058-0360(2011/09-0102). ISSN 1058-0360. PMC 3738062. PMID 21478281.

- Iverach, Lisa; Rapee, Ronald M. (June 2014). "Social anxiety disorder and stuttering: Current status and future directions". Journal of Fluency Disorders. 40: 69–82. doi:10.1016/j.jfludis.2013.08.003. PMID 24929468.

- St. Louis, Kenneth O.; Hinzman, Audrey R. (October 1988). "A descriptive study of speech, language, and hearing characteristics of school-aged stutterers". Journal of Fluency Disorders. 13 (5): 331–355. doi:10.1016/0094-730X(88)90003-4.

- ^ Bloodstein, Oliver; Ratner, Nan Bernstein (2007). A handbook on stuttering. Cengage Learning. p. 142. ISBN 978-1418042035.

- "Brain Development in Children Who Stutter | Stuttering Foundation: A Nonprofit Organization Helping Those Who Stutter". Stutteringhelp.org. 1955-12-04. Archived from the original on 2014-05-12. Retrieved 2014-05-12.

- "NIH study in mice identifies type of brain cell involved in stuttering". NIDCD. 2019-08-16. Retrieved 2021-05-16.

- ^ Gordon, N. (2002). "Stuttering: incidence and causes". Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 44 (4): 278–81. doi:10.1017/S0012162201002067. PMID 11995897.

- ^ Guitar 2005, pp. 5–6 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFGuitar2005 (help)

- Ward 2006, p. 11

- ^ Guitar 2005, p. 66 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFGuitar2005 (help)

- Guitar 2005, p. 39 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFGuitar2005 (help)

- Kang, Changsoo; Riazuddin, Sheikh; Mundorff, Jennifer; Krasnewich, Donna; Friedman, Penelope; Mullikin, James C.; Drayna, Dennis (2010-02-25). "Mutations in the Lysosomal Enzyme–Targeting Pathway and Persistent Stuttering". New England Journal of Medicine. 362 (8): 677–685. doi:10.1056/nejmoa0902630. ISSN 0028-4793. PMC 2936507. PMID 20147709.

- "Genetic Mutations Linked to Stuttering". Children.webmd.com. February 10, 2010. Archived from the original on November 12, 2012. Retrieved August 13, 2012.

- Ward 2006, p. 12

- West, R.; Nelson, S.; Berry, M. (1939). "The heredity of stuttering". Quarterly Journal of Speech. 25 (1): 23–30. doi:10.1080/00335633909380434.

- ^ Watkins KE, Smith SM, Davis S, Howell P (January 2008). "Structural and functional abnormalities of the motor system in developmental stuttering". Brain. 131 (Pt 1): 50–9. doi:10.1093/brain/awm241. PMC 2492392. PMID 17928317.

- Soo-Eun, Chang (2007). "Brain anatomy differences in childhood stuttering". NeuroImage.

- ^ Sander, RW; Osborne, CA (1 November 2019). "Stuttering: Understanding and Treating a Common Disability". American Family Physician. 100 (9): 556–560. PMID 31674746.

- Ward 2006, pp. 46–7

- Ward 2006, p. 58

- Ward 2006, p. 43

- Ward 2006, pp. 16–21

- "Neurogenic Stuttering". Stuttering Foundation: A Nonprofit Organization Helping Those Who Stutter. 6 May 2011. Retrieved 2020-01-29.

- "Stuttering". NIDCD. 2015-08-18. Archived from the original on 2018-05-20. Retrieved 2020-01-29.

- ^ http://cirrie.buffalo.edu/encyclopedia/en/article/158/#s4International Archived 2013-11-10 at the Wayback Machine Fibiger S. 2009. Stuttering. In: JH Stone, M Blouin, editors. International Encyclopedia of Rehabilitation.

- Encyclopedia of Rehabilitation Archived 2013-11-10 at the Wayback Machine

- "Trobe University School of Human Communication Disorders".

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, D.C.: Author.

- Ambrose, Nicoline Grinager, and Ehud Yairi. "Normative Disfluency Data for Early Childhood Stuttering." Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 42, no. 4 (1999): 895–909. https://doi.org/10.1044/jslhr.4204.895 ("Stuttering is shown to be qualitatively as well as quantitatively different from normal disfluency even at the earliest stages of stuttering.")

- ^ Craig, A.; Tran, Y. (2005). "The epidemiology of stuttering: The need for reliable estimates of prevalence and anxiety levels over the lifespan". Advances in Speech Language Pathology. 7 (1): 41–46. doi:10.1080/14417040500055060. S2CID 71565512.

- ^ Yairi, E.; Ambrose, N. (1992). "Onset of stuttering in preschool children: selected factors". Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 35 (4): 782–8. doi:10.1044/jshr.3504.782. PMID 1405533.

- Ward 2006, pp. 114–5

- Ward 2006, pp. 115–116

- Ward 2006, pp. 4, 332–335

- Ward 2006, pp. 4, 332, 335–337

- Yaruss, J Scott (Feb 2003). "One size does not fit all: special topics in stuttering therapy". Semin Speech Lang (24): 3-6. doi:10.1055/s-2003-37381.

- Ward 2006, p. 257

- Ward 2006, p. 253

- Ward 2006, p. 245

- Stuttering, Stammering Archived 2012-09-10 at the Wayback Machine

- Yairi, E. (1993). "Epidemiologic and other considerations in treatment efficacy research with preschool-age children who stutter". Journal of Fluency Disorders. 18 (2–3): 197–220. doi:10.1016/0094-730X(93)90007-Q.

- ^ Ward 2006, p. 16

- Yairi, E (Fall 2005). "On the Gender Factor in Stuttering". Stuttering Foundation of America Newsletter: 5.

- ^ Yairi, E.; Ambrose, N. (2005). "Early childhood stuttering". Pro-Ed.

- Andrews, G.; Craig, A.; Feyer, A. M.; Hoddinott, S.; Howie, P.; Neilson, M. (1983). "Stuttering: a review of research findings and theories circa 1982". The Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders. 48 (3): 226–46. doi:10.1044/jshd.4803.226. PMID 6353066.

- Mansson, H. (2000). "Childhood stuttering: Incidence and development". Journal of Fluency Disorders. 25 (1): 47–57. doi:10.1016/S0094-730X(99)00023-6.

- Yairi, E; Ambrose, N; Cox, N (1996). "Genetics of stuttering: a critical review". Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 39 (4): 771–784. doi:10.1044/jshr.3904.771. PMID 8844557.

- ^ Kloth, S; Janssen, P; Kraaimaat, F; Brutten, G (1995). "Speech-motor and linguistic skills of young people who stutter prior to onset". Journal of Fluency Disorders. 20 (2): 157–70. doi:10.1016/0094-730X(94)00022-L. hdl:2066/21168. S2CID 146130424.

- Guitar 2005, p. 22 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFGuitar2005 (help)

- Yairi, E.; Ambrose, N. G. (1999). "Early childhood stuttering I: persistency and recovery rates". Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 42 (5): 1097–112. doi:10.1044/jslhr.4205.1097. PMID 10515508.

- Craig, A.; Hancock, K.; Tran, Y.; Craig, M.; Peters, K. (2002). "Epidemiology of stuttering in the community across the entire life span". Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 45 (6): 1097–105. doi:10.1044/1092-4388(2002/088). PMID 12546480.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Proctor, A.; Duff, M.; Yairi, E. (2002). "Early childhood stuttering: African Americans and European Americans". ASHA Leader. 4 (15): 102.

- Nwokah, E (1988). "The imbalance of stuttering behavior in bilingual speakers". Journal of Fluency Disorders. 13 (5): 357–373. doi:10.1016/0094-730X(88)90004-6.

- Sheree Reese, Joseph Jordania (2001). "Stuttering in the Chinese population in some Southeast Asian countries: A preliminary investigation on attitude and incidence". "Stuttering Awareness Day"; Minnesota State University, Mankato. Archived from the original on 2011-06-06.

- ^ Brosch, S; Pirsig, W. (2001). "Stuttering in history and culture". Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 59 (2): 81–7. doi:10.1016/S0165-5876(01)00474-8. PMID 11378182.

- ^ Rieber, RW; Wollock, J (1977). "The historical roots of the theory and therapy of stuttering". Journal of Communication Disorders. 10 (1–2): 3–24. doi:10.1016/0021-9924(77)90009-0. PMID 325028.

- "Churchill: A Study in Oratory". The Churchill Centre. Archived from the original on 2005-04-19. Retrieved 2005-04-05.

- "Churchill Stutter". Archived from the original on 2012-01-13. Retrieved 2012-01-28.

- ^ Kuster, Judith Maginnis (2005-04-01). "Folk Myths About Stuttering". Minnesota State University. Archived from the original on 2005-04-19. Retrieved 2005-04-03.

- "Did I Stutter?". Did I Stutter?. Archived from the original on 2015-10-06. Retrieved 2015-10-05.

- "How To Stutter More". stuttermore.tumblr.com. Archived from the original on 2015-10-29. Retrieved 2015-10-05.

- "Defence Stammering Network launched". Archived from the original on 2015-08-25. Retrieved 2015-07-25.

- ^ "Stuttering and the Bilingual Child". Stuttering Foundation: A Nonprofit Organization Helping Those Who Stutter. 6 May 2011. Archived from the original on 2017-09-26. Retrieved 2017-12-18.

- Kornisch, Myriam (2020 Dec 3). "Bilinguals who stutter: A cognitive perspective". Journal of Fluency Disorders. doi:10.1016/j.jfludis.2020.105819. PMID 33296800.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Howell, Peter; Borsel, John Van (2011). Multilingual Aspects of Fluency Disorders. Multilingual Matters. ISBN 9781847693587.

- Awards and Recognition Archived 2008-12-05 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2009-12-10.

- Behrens, David (25 July 2020). "Where Arkwright in Open All Hours found his signature stutter". Yorkshire Post. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- Nirmal, Gayatri (2017-08-09). "Due to societal pressure, Shreyas won't stammer in Golmaal 4, but has another quirk". Deccan Chronicle. Retrieved 2023-01-10.

- "Stammering Groups | STAMMA". stamma.org. Retrieved 2023-07-23.

- "Local NSA Chapters | Stuttering Support Groups". National Stuttering Association. Retrieved 2023-07-23.

- Thurber, James (1930-04-25). "Stammerers' Club". The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X. Retrieved 2023-08-01.

- "Fraser's Magazine for Town and Country, 1830–1882", Perceptions of the Press in Nineteenth-Century British Periodicals, Anthem Press, pp. 261–299, 2012-02-01, doi:10.7135/upo9781843317562.019, ISBN 9781843317562, retrieved 2023-08-01

- "STAMMERERS' CLUB". Sydney Morning Herald. 1935-05-23. Retrieved 2023-08-01.

- "THE STAMMERERS' CLUB OF QUEENSLAND". Cairns Post. 1936-10-10.

- ^ Stammering pride and prejudice : difference not defect. Patrick Campbell, Christopher Constantino, Sam Simpson. . 2019. ISBN 978-1-907826-36-8. OCLC 1121135480.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link)

Further reading

- Rockey, D., Speech Disorder in Nineteenth Century Britain: The History of Stuttering, Croom Helm, (London), 1980. ISBN 0-85664-809-4

- Goldmark, Daniel. "Stuttering in American Popular Song, 1890–1930." In Lerner, Neil (2006). Sounding Off: Theorizing Disability in Music. New York, London: Routledge. pp. 91–105. ISBN 978-0-415-97906-1.

- Ward, David (2006). Stuttering and Cluttering: Frameworks for understanding treatment. Hove and New York City: Psychology Press. ISBN 978-1-84169-334-7.

External links

Listen to this article(3 parts, 52 minutes)

| Classification | D |

|---|---|

| External resources |

| Emotional and behavioral disorders | |

|---|---|

| Emotional/behavioral |

|