| Revision as of 02:31, 4 March 2024 editHeadbomb (talk | contribs)Edit filter managers, Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Page movers, File movers, New page reviewers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers, Template editors454,554 edits ce← Previous edit | Revision as of 02:31, 4 March 2024 edit undoCitation bot (talk | contribs)Bots5,438,835 edits Altered title. Added doi. | Use this bot. Report bugs. | Suggested by Headbomb | #UCB_toolbarNext edit → | ||

| Line 237: | Line 237: | ||

| {{Refbegin}} | {{Refbegin}} | ||

| * {{cite book|title=Four Seasons: A Ming Emperor and His Grand Secretaries in Sixteenth-Century China|first=John W|last=Dardess|year=2016|publisher=Rowman & Littlefield|url=|location=Lanham, Maryland|isbn=9781442265608}} | * {{cite book|title=Four Seasons: A Ming Emperor and His Grand Secretaries in Sixteenth-Century China|first=John W|last=Dardess|year=2016|publisher=Rowman & Littlefield|url=|location=Lanham, Maryland|isbn=9781442265608}} | ||

| * {{cite journal|title=On the significance of the reign title Chia-ching|first=James|last=Geiss|year=1990|journal=Ming Studies|url=|volume=|issue=1|issn=}} | * {{cite journal|title=On the significance of the reign title Chia-ching|first=James|last=Geiss|year=1990|journal=Ming Studies|url=|volume=|issue=1|doi=10.1179/014703790788763857 |issn=}} | ||

| * {{cite book|chapter=The Chia-ching reign, 1522-1566|title=The Cambridge History of China. Volume 7, The Ming Dynasty 1368-1644, Part 1|first=James|last=Geiss|editor-first2=Denis C|editor-last2=Twitchett|editor-first1=Frederick W.|editor-last1=Mote|year=1998|publisher=Cambridge University Press|url=|location=Cambridge|isbn=0521243335|pages=440–510|edition=1}} | * {{cite book|chapter=The Chia-ching reign, 1522-1566|title=The Cambridge History of China. Volume 7, The Ming Dynasty 1368-1644, Part 1|first=James|last=Geiss|editor-first2=Denis C|editor-last2=Twitchett|editor-first1=Frederick W.|editor-last1=Mote|year=1998|publisher=Cambridge University Press|url=|location=Cambridge|isbn=0521243335|pages=440–510|edition=1}} | ||

| * {{cite book|title=Dictionary of Ming Biography, 1368-1644|first1=L. Carington|last1=Goodrich|first2=Chaoying|last2=Fang|year=1976|publisher=Columbia University Press|url=|location=New York|isbn=0-231-03801-1|volume=1, A-L}} | * {{cite book|title=Dictionary of Ming Biography, 1368-1644|first1=L. Carington|last1=Goodrich|first2=Chaoying|last2=Fang|year=1976|publisher=Columbia University Press|url=|location=New York|isbn=0-231-03801-1|volume=1, A-L}} | ||

| * {{cite journal|title=Building an Immortal Land: The Ming Jiajing |

* {{cite journal|title=Building an Immortal Land: The Ming Jiajing Emperor's West Park|first=Maggie C. K|last=Wan|year=2009|journal=Asia Major |series=Third Series|url=|volume=22|issue=2|pages=65–99|issn=0021-9118}} | ||

| * {{cite book|title=China's Second Capital – Nanjing under the Ming, 1368-1644|first=Jun|last=Fang|year=2014|publisher=Routledge|url=|location=Abingdon, Oxon|isbn=9780415855259}} | * {{cite book|title=China's Second Capital – Nanjing under the Ming, 1368-1644|first=Jun|last=Fang|year=2014|publisher=Routledge|url=|location=Abingdon, Oxon|isbn=9780415855259}} | ||

| * {{cite book|title=The Ming Maritime Policy in Transition, 1367 to 1568|first=Kangying|last=Li|year=2010|publisher=Otto Harrassowitz|url=|location=Wiesbaden|isbn=978-3-447-06172-8}} | * {{cite book|title=The Ming Maritime Policy in Transition, 1367 to 1568|first=Kangying|last=Li|year=2010|publisher=Otto Harrassowitz|url=|location=Wiesbaden|isbn=978-3-447-06172-8}} | ||

Revision as of 02:31, 4 March 2024

12th emperor of the Ming dynasty (r. 1521–1567) Not to be confused with Jiaqing Emperor.

| Jiajing Emperor 嘉靖帝 | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Palace portrait on a hanging scroll, kept in the National Palace Museum, Taipei, Taiwan Palace portrait on a hanging scroll, kept in the National Palace Museum, Taipei, Taiwan | |||||||||||||||||

| Emperor of the Ming dynasty | |||||||||||||||||

| Reign | 27 May 1521 – 23 January 1567 | ||||||||||||||||

| Enthronement | 27 May 1521 | ||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Zhengde Emperor | ||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Longqing Emperor | ||||||||||||||||

| Prince of Xing | |||||||||||||||||

| Tenure | 15 April 1521 – 27 May 1521 | ||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Zhu Youyuan, Prince Xian of Xing | ||||||||||||||||

| Born | 16 September 1507 Zhengde 2, 10th day of the 8th month (正德二年八月初十日) Anluzhou, Huguang Province, Ming dynasty | ||||||||||||||||

| Died | 23 January 1567(1567-01-23) (aged 59) Jiajing 45, 14th day of the 12th month (嘉靖四十五年十二月十四日) Palace of Heavenly Purity, Forbidden City, Beijing, Ming dynasty | ||||||||||||||||

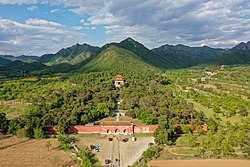

| Burial | Yongling Mausoleum, Ming tombs, Beijing | ||||||||||||||||

| Consorts |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Issue Detail | |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| House | Zhu | ||||||||||||||||

| Dynasty | Ming | ||||||||||||||||

| Father | Zhu Youyuan | ||||||||||||||||

| Mother | Empress Cixiaoxian | ||||||||||||||||

The Jiajing Emperor (Chinese: 嘉靖帝; pinyin: Jiājìng Dì; Wade–Giles: Chia-ching Ti; 16 September 1507 – 23 January 1567), also known by his temple name as the Emperor Shizong of Ming (明世宗), personal name Zhu Houcong (朱厚熜), was the 12th emperor of the Ming dynasty, reigning from 1521 to 1567. He succeeded his cousin, the Zhengde Emperor. "Jiajing", the era name of his reign, means "admirable tranquility".

Zhu Houcong was born as a cousin of the reigning Zhengde Emperor, so his accession to the throne was unexpected. However, when the Zhengde Emperor died without an heir, the government, led by Senior Grand Secretary Yang Tinghe and the Empress Dowager Zhang, chose Zhu Houcong as the new ruler. However, after his enthronement, a dispute arose between the emperor and most of the officials regarding the method of legalizing his accession. The Great Rites Controversy was a major political problem at the beginning of his reign. After three years, the emperor emerged victorious, with his main opponents either banished from court or executed.

The Jiajing Emperor, like the Zhengde Emperor, made the decision to reside outside of Beijing's Forbidden City. In 1542, he relocated to the West Park, located in the middle of Beijing and west of the Forbidden City. He constructed a complex of palaces and Taoist temples in the West Park, drawing inspiration from the Taoist belief of the Land of Immortals. Within the West Park, he surrounded himself with a group of loyal eunuchs, Taoist monks, and trusted advisers (including Grand Secretaries and Ministers of Rites) who assisted him in managing the state bureaucracy. The Jiajing Emperor's team of advisers and Grand Secretaries were led by Zhang Fujing (張孚敬), Xia Yan, Yan Song, and Xu Jie in succession.

At the start of the Jiajing Emperor's reign, the borders were relatively peaceful. In the north, the Mongols were initially embroiled in internal conflicts. However, after being united by Altan Khan in the 1540s, they began to demand the restoration of free trade. The emperor, however, refused and attempted to close the borders with fortifications, including the Great Wall of China. In response, Altan Khan launched raids and even attacked the outskirts of Beijing in 1550. The Ming troops were forced to focus on defense. The conflict only came to an end after Jiajing's death, when the new Ming emperor Longqing allowed trade to resume.

In the Jiajing era, Wokou pirates posed a significant threat to the southeastern provinces of Zhejiang, Fujian, and Guangdong for several decades. The Ming authorities attempted to address this issue by implementing stricter laws against private overseas trade in the 1520s. However, piracy and related violence continued to escalate throughout the 1540s and reached its peak in the 1550s. It was not until the 1560s, particularly after 1567 when the Longqing Emperor relaxed laws against maritime trade with foreign countries, that the problem began to be gradually suppressed.

In 1556, northern China was struck by a devastating natural disaster—the deadliest earthquake in human history, with its epicenter in Shaanxi. The earthquake claimed the lives of over 800,000 people. Despite the destruction caused by the disaster, the economy continued to develop, with growth in agriculture, industry, and trade. As the economy flourished, so did society, with the traditional Confucian interpretation of Zhuism giving way to Wang Yangming's more individualistic beliefs.

However, in his later years, the emperor's pursuit of immortality led to questionable actions, such as his interest in young girls and alchemy. He even sent Taoist priests across the land to collect rare minerals for life-extending potions. Unfortunately, these elixirs contained harmful substances like arsenic, lead, and mercury, which ultimately caused health problems and may have shortened the emperor's life.

Childhood

Zhu Houcong was born on 16 September 1507. He was the eldest son of Zhu Youyuan, who was Prince of Xing from 1487. Zhu Youyuan was the fourth son of the Chenghua Emperor, who ruled the Ming dynasty from 1464 to 1487. His mother, Lady Shao, was one of the emperor's concubines. Zhu Houcong's mother, surnamed Jiang, was the daughter of Jiang Xiao of Daxing in North Zhili. Jiang Xiao was an officer of the Beijing garrison. Zhu Houcong's parents from 1494 lived in Anlu zhou (present-day Zhongxiang) in Hguang in central China, where Zhu Houcong was born. His father, Zhu Youyuan, was known for his poetry and calligraphy.

Zhu Houcong received a classical (Confucian) education directly from his father, who he was a diligent and attentive student to. However, in July 1519, his father died. After this, Zhu Houcong took on the responsibility of managing the household with the assistance of Yuan Zonggao, a capable administrator who later became a trusted advisor after Zhu Houcong's ascension to the throne in Beijing. Following the traditional period of mourning for his father's death, Zhu Houcong officially became the Prince of Xing in late March 1521.

Beginning of reign

Accession

Meanwhile, in Beijing, the Zhengde Emperor (ruled 1505–1521) fell ill and died on 20 April 1521. The Zhengde Emperor was the son of the Hongzhi Emperor (ruled 1487–1505) and the older brother of Zhu Youyuan. Zhu Houcong was Zhengde's cousin and closest male relative.

Before the death of the Zhengde Emperor, Grand Secretary Yang Tinghe, who was effectively leading the Ming government, had already begun preparations for the accession of Zhu Houcong. Five days prior to the Zhengde Emperor's death, an edict was issued ordering Zhu Houcong to end his mourning and officially assume the title of Prince of Xing. On the day of the emperor's death, Yang Tinghe, with the support of eunuchs from the Directorate of Ceremonial in the Forbidden City and Empress Dowager Zhang (the late emperor's mother), issued an edict calling for the prince to arrive in Beijing and ascend the throne.

However, there was uncertainty surrounding this matter due to the Ming succession law. According to this law, although Ming emperors were allowed to have multiple wives, only the sons of the first wife, the empress, had the right to succeed the throne. Any attempt to install a descendant of a secondary wife was punishable by death. Zhu Houcong's father, Zhu Youyuan, was not the son of the empress, but rather of a secondary wife, therefore he had no legitimate claim to the throne. In order to circumvent this issue, Yang Tinghe proposed adopting Zhu Houcong as the Hongzhi Emperor's son, so he could ascend as the late emperor's younger brother.

In addition, there were many favorites of the deceased emperor living in Beijing who were afraid of changes. The most influential among them was General Jiang Bin, the commander of the border troops who had been transferred to Beijing. It was feared that he would try to install his own candidate for the throne, namely Zhu Junzhang (朱俊杖), Prince of Dai, who was based in the border city of Datong.

| The proposal for the era name "Shaozhi" ("Continuation of proper governance") by the Grand Secretaries was rejected by the Jiajing Emperor. It is believed that "Shaozhi" was a summary of the government's call for the Jiajing Emperor to take the throne and follow the policies and rituals set by the founders of the dynasty in order to ensure proper governance. This expressed a desire for continuity in rule. The era name "Jiajing" means "admirable and tranquility" and is derived from a passage in the Book of Documents, in which the Duke of Zhou admonishes the young King Cheng and praises King Wu Ding of the Shang dynasty for his admirable and tranquil leadership. Wu Ding was commended for restoring the fallen prestige of the Shang dynasty not through force, but through the radiance of his virtue. Therefore, the era name "Jiajing" can be seen as a criticism of the state of the country and the Zhengde regime, as well as a declaration of a policy of change and restoration.

In the mentioned reprimand, King Wen, the father of the founder of the Zhou dynasty, King Wu, is also contrasted with the unworthy last Shang king, Zhou. The Jiajing Emperor saw a parallel between King Wen, Zhou and Wu, and his noble father, unworthy Zhengde Emperor, and himself. Therefore, he judged that he did not owe the throne to the Grand Secretaries, ministers, or the empress dowager, but to the virtues of his father recognized by the Heavens. This was the basis of his respect for his parents and his rejection of adoption in the dispute over rituals. |

The day after the Zhengde Emperor's death, a delegation of high-ranking dignitaries left Beijing for Anlu to inform the prince of the situation. They arrived in Anlu on 2 May. Zhu Houcong accepted them, familiarized himself with the edict of the empress dowager, and agreed to ascend the throne. On 7 May, he set out for Beijing accompanied by forty of his own advisers and servants. Yang Tinghe issued orders for him to be welcomed in Beijing as the heir to the throne, but Zhu Houcong refused to appear as the heir apparent, stating that he was invited to assume the imperial rank and was therefore the emperor, not the son of the emperor. According to the Grand Secretaries and the government, he was the son of the Hongzhi Emperor. He forced his way into the city with imperial honors and on the same day, 27 May 1521, he ceremoniously ascended the throne. The young emperor reportedly chose the name of his era himself, from his favorite chapter of the Book of Documents, with jia meaning "to improve, make splendid" and jing meaning "to pacify" in Chinese.

Great Rites Controversy

Further information: Great Rites Controversy

The primary desire of the new emperor was to posthumously elevate his father to the imperial rank. In contrast, Yang Tinghe insisted on his formal adoption by the Hongzhi Emperor, in order to legitimize his claim to the throne and become the younger brother of the late Zhengde Emperor. However, the Jiajing Emperor and his mother rejected the adoption, citing the wording of the recall decree which did not mention it. The emperor did not want to declare his parents as his uncle and aunt. Instead, he requested the elevation of his parents to the imperial status "to bring their ranks into line."

Most officials agreed to maintain a direct line of succession and supported Yang Tinghe, but the emperor argued for the duty to his biological parents. He insisted on his mother's acceptance as Empress dowager when she arrived from Anlu and entered the Forbidden City on 2 November. A group of officials, led by Zhang Fujing (張孚敬) and standing on the side of the emperor, had already formed. In late 1521, the Jiajing Emperor succeeded in having his parents and grandmother, Lady Shao, granted imperial rank. However, disputes continued until Yang Tinghe was forced to resign in March 1524, and the removal of the emperor's opponents began in August 1524. After a disapproving demonstration by hundreds of opposing officials in front of the gates of the audience hall, the opposition was beaten at court. 17 officials died from their wounds, and the rest were exiled to the provinces by the emperor.

During the dispute, the Jiajing Emperor asserted his independence from the Grand Secretaries and made decisions based on his own judgment, rather than consulting with them or simply approving their proposals. This was seen as a despotic approach that went against the traditional way of governing, and was criticized by concerned scholars. As a result of the dispute, the teachings of Confucian scholar and reformer Wang Yangming gained popularity, as some of the emperor's followers were influenced by his arguments. Additionally, there was an increase in critical analysis and interpretation of texts during discussions, and there was a growing criticism of the conservative attitudes of the Hanlin Academy.

Honoring parents and legitimizing the government

In 1530, the Jiajing Emperor published the biography of Empress Ma, the Gao huanghou chuan (高皇后傳), and the Household Instructions of Empress Xu under the title Nüxun (女訓, 'Instructions for women', in 12 volumes). The work was attributed to the emperor's mother. Empress Ma was the wife of the Hongwu Emperor, the founder of the dynasty, and Empress Xu was the wife of the Yongle Emperor, the first monarch in the new branch of the dynasty. Additionally, the emperor changed the Yongle Emperor's temple name from "Taizong" to "Chengzu". It is believed that Jiajing's interest in the Yongle Emperor stemmed from the precedent of starting a new branch of the dynasty.

The emperor also suggested transferring his father's remains from the mausoleum in Huguang to the vicinity of the imperial burial ground near Beijing. However, in the end, only a shrine was created for him in the palace. The emperor also took steps to honor his ancestors, such as restoring ancestral temples, giving his parents longer titles, and supervising rituals and ritual music. After his mother's death in December 1538, the emperor traveled south to Anlu to resolve the question of whether to bury his parents together in the south or in Beijing. He ultimately chose to bury his mother in his father's mausoleum near Zhongxiang. In honor of his father, he also published his Veritable Records (Shilu) and renamed Anlu zhou to Chengtian Prefecture (承天府, Chengtian Fu) after the example of the imperial capitals.

During his journey to Anlu, the Jiajing Emperor was shocked by the sight of starving and impoverished people and refugees. He immediately released 20 thousand liang (746 kg) of silver for relief. He saw their suffering as a failure of his ceremonial and administrative reforms. Two years later, during civil service examinations, he asked candidates why there was still poverty in the country despite his efforts to faithfully follow Confucian teachings and observe ceremonies.

Further ceremony reforms

After successfully resolving the Great Rites Controversy, the emperor proceeded to make changes to other rituals and ceremonies, despite facing opposition from some officials. These changes primarily affected the rites performed by the monarch. In the late 1530s, separate sacrifices to the Heavens, Earth, Sun, and Moon were introduced.

Additionally, the Jiajing Emperor altered the titles and forms of honoring Confucius, including a ban on images in Confucius temples, leaving only plaques with the names of Confucius and his followers. The layout of the Temple of Confucius was also modified to include separate chapels for Confucius' father and three disciples. As part of these changes, Confucius was stripped of his title of king by the Jiajing Emperor, who believed that the emperor should not bow to a king. Furthermore, the emperor did not want Confucius to be worshipped in the same rituals used for imperial sacrifices to the Heavens. As a result, the ceremonies in the Temple of Confucius were simplified and no longer resembled imperial sacrifices.

In addition, sacrifices to former emperors and kings were separated from the imperial sacrifices to the Heavens, and a special temple was built for them. This elevated the status of the monarch, as his rites were now distinct from all others. However, from the years 1532–1533, the Jiajing Emperor lost interest in ritual reforms and the worship of Heaven, as he was no longer able to elevate his own or his father's status. This led to a decline in the importance of ceremonies during his reign.

Government

Eunuchs

Important positions in the imperial palace were filled by eunuchs brought from Anlu by the Jiajing Emperor. As part of the dismissal of eunuchs associated with the previous monarch, some eunuch posts in the provinces were eliminated. However, the overall influence of eunuchs did not decrease; in fact, it continued to grow. By the 1530s, the most influential eunuchs saw themselves as equal to the Grand Secretaries. In 1548–1549, the roles of the head of the Eastern Depot and the Directorate of Ceremonial were combined, and the palace guard (established in 1552 and composed of eunuchs) was also under their control. This effectively placed the entire eunuch branch of state administration under their management.

Grand Secretaries

After 1524, the emperor's closest advisers were Zhang Fujing and Gui E (桂萼). They attempted to remove followers of Yang Tinghe, who were associated with the Hanlin Academy, from influential positions. This resulted in a purge of the Beijing authorities in 1527–1528 and a significant change in personnel at the academy. In addition, Zhang Fujing and Gui E worked to limit the influence of Senior Grand Secretary, Fei Hong (費宏), in the Grand Secretariat. To balance this, they brought back Yang Yiqing, who had previously served in the Grand Secretariat in 1515–1516. In the following years, there was a power struggle between the Grand Secretaries and their associated groups of officials. The position of Senior Grand Secretary was constantly changing, with Fei Hong, Yang Yiqing, Zhang Fujing, and others taking turns.

In the early 1530s, the Jiajing Emperor's trust was won by Xia Yan, who had been promoted from Minister of Rites to Grand Secretary. Later, in the late 1530s, Yan Song, Xia Yan's successor in the ministry, also gained the Jiajing Emperor's trust. However, despite initially supporting Yan Song's rise, Xia Yan and Yan Song eventually came into conflict. In 1542, Yan Song was able to oust Xia Yan and take control of the Grand Secretariat. In an attempt to counterbalance Yan Song's influence, the emperor called Xia Yan back to lead the Grand Secretariat in October 1545. However, the two statesmen were at odds, with Xia Yan ignoring Yan Song, refusing to consult him, and canceling his appointment. As a result, the emperor grew distant from Xia Yan, partly due to his reserved attitude towards Taoist rituals and prayers. In contrast, Yan Song strongly supported the emperor's interest in Taoism. In February 1548, Xia Yan supported a campaign to Ordos without informing Yan Song, making him solely responsible for it. When the emperor withdrew his support for the campaign due to unfavorable omens and reports of discontent in the neighboring province of Shaanxi, enemies of Xia Yan, including Yan Song, used this as an opportunity to bring charges against him and have him executed.

From 1549 to 1562, the Grand Secretariat was under the control of Yan Song. He was known for his attentiveness and diligence towards the monarch, but also for pushing his colleagues out of power. Despite facing numerous political crises and challenges, Yan Song managed to survive by delegating decisions and responsibilities to the appropriate ministries and authorities. For example, the Ministry of Rites was responsible for dealing with the Mongols, while the Ministry of War handled their expulsion. However, Yan Song avoided getting involved in the government's biggest issue at the time—state finances—leaving it to the Ministries of Revennue and Works. He only maintained control over personnel matters and selected political issues. Despite facing criticism for corruption and selling offices, Yan Song was able to convince the emperor that these were false accusations and that his critics were simply trying to remove him from power. The emperor, who was always suspicious of officials, believed Yan Song's defense.

Yan Song, who was already eighty years old in 1560, was unable to continue his role as Grand Secretary. This was especially true after his wife died in 1561 and his son, who had been assisting him with writing edicts, went home to organize the funeral. To make matters worse, he faced opposition from his subordinate, Grand Secretary Xu Jie. As a result, the emperor no longer relied on Yan Song and dismissed him in June 1562. Xu Jie then took over as the head of the Grand Secretariat.

With the personnel changes in the immediate surroundings of the emperor, the focus and style of his policies also shifted. During the first phase of his reign, the Jiajing Emperor placed great importance on ceremonies, which were seen as essential in maintaining order and promoting a sense of superiority over non-Chinese peoples, according to Confucian beliefs. The refinement and organization of these ceremonies aimed to showcase the Ming dynasty as a model for surrounding countries and the world. The emperor received significant assistance from his Senior Grand Secretary, Zhang Fujing. However, during Xia Yan's dominance in the Grand Secretariat, the emperor withdrew from the Forbidden City to the West Park, neglecting his public duties but still maintaining control over the government. During this time, Ming China used military force to intimidate neighboring countries, successfully in the case of Vietnam, but falling in the attempt to recapture Ordos, resulting in Xia Yan's death in 1548. In the following period, during the conflicts of the 1550s in the north and on the coast, Yan Song pursued a policy of compromise and negotiation, which was accompanied by corruption. After the fall of Yan Song in 1562, the emperor's interest in good governance was rekindled under the influence of the capable and energetic Grand Secretary, Xu Jie. Thus, the Jiajing Emperor's rule after the overthrow of Yang Tinghe can be divided into four phases: Zhang Fujing's strict adherence to ideology, Xia Yan's aggressive expansionism, Yan Song's complacent corruption, and Xu Jie's corrective reforms.

Reign as emperor

Custom dictated that an emperor who was not an immediate descendant of the previous one should be adopted by the previous one, to maintain an unbroken line. Such a posthumous adoption of Zhu Houcong by the Hongzhi Emperor was proposed, but he resisted, preferring instead to have his father declared emperor posthumously. This conflict is known as the Great Rites Controversy, in which the emperor prevailed, and hundreds of his opponents were banished, flogged in the imperial court (廷杖), or executed. Among the banished was the poet Yang Shen.

The Jiajing Emperor was known to be intelligent and efficient; while later he went on strike, and chose not to attend any state meetings, he did not neglect the paperwork and other governmental matters. The Jiajing Emperor was also known to be a cruel and self-aggrandizing emperor and he also chose to reside outside of the Forbidden City in Beijing so he could live in isolation. Ignoring state affairs, the Jiajing Emperor relied on Zhang Cong and Yan Song to handle affairs of state. In time, Yan Song and his son Yan Shifan – who gained power only as a result of his father's political influence – came to dominate the whole government, even being called the "First and Second Prime Minister". Ministers such as Hai Rui and Yang Jisheng challenged and even chastised Yan Song and his son but were thoroughly ignored by the emperor. Hai Rui and many ministers were eventually dismissed or executed. The Jiajing Emperor also abandoned the practice of seeing his ministers altogether from 1539 onwards, and for a period of almost 25 years refused to give official audiences, choosing instead to relay his wishes through eunuchs and officials. Only Yan Song, a few handful of eunuchs and Daoist priests ever saw the emperor. This eventually led to corruption at all levels of the Ming government. However, the Jiajing Emperor was intelligent and managed to control the court.

The Ming dynasty had enjoyed a long period of peace, but in 1542 the Mongol leader Altan Khan began to harass China along the northern border. In 1550, he even reached the suburbs of Beijing. Eventually the Ming government appeased him by granting special trading rights. The Ming government also had to deal with wokou pirates attacking the southeastern coastline. Starting in 1550, Beijing was enlarged by the addition of the outer city.

Palace plot of Renyin year

Main article: Palace plot of Renyin yearDue to the Jiajing Emperor's cruelty and promiscuous lifestyle, his concubines and palace maids plotted to assassinate him in October 1542 by strangling him while he slept. His pursuit of eternal life led him to believe that one of the elixirs of extending his life was to force virgin palace maids to collect menstrual blood for his consumption. These arduous tasks were performed non-stop even when the palace maids were taken ill and any unwilling participants were executed on the Emperor's whim. A group of palace maids who had had enough of the emperor's cruelty decided to band together to murder him in an event known as the Palace plot of Renyin year. The lead palace maid tried to strangle the emperor with ribbons from her hair while the others held down the emperor's arms and legs but made a fatal mistake by tying a knot around the emperor's neck which would not tighten. Meanwhile, some of the young palace maids involved began to panic and one (Zhang Jinlian) ran to the empress. The plot was exposed and on the orders of the empress and some officials, all of the palace maids involved, including the emperor's favourite concubine (Consort Duan) and another concubine (Consort Ning, née Wang), were ordered to be executed by slow slicing and their families were killed. The Jiajing Emperor later determined that Consort Duan had been innocent, and dictated that their daughter, Luzheng, be raised by Imperial Noble Consort Shen.

Taoist pursuits

The Jiajing Emperor was a devoted follower of Taoism and attempted to suppress Buddhism. After the assassination attempt in 1542, the emperor moved out of the imperial palace, and lived with a small, thin, 13-year-old girl who was able to satisfy his sexual appetite (Lady Shan). The Jiajing Emperor began to pay excessive attention to his Taoist pursuits while ignoring his imperial duties. He built three Taoist temples: Temple of the Sun, Temple of the Earth and Temple of the Moon, and extended the Temple of Heaven by adding the Earthly Mount. Over the years, the emperor's devotion to Taoism was to become a heavy financial burden for the Ming government and create dissent across the country.

Particularly during his later years, the Jiajing Emperor was known for spending a great deal of time on alchemy in hopes of finding medicines to prolong his life. He would forcibly recruit young women in their early teens and engage in sexual activities in the hope of empowering himself, along with the consumption of potent elixirs. He employed Taoist priests to collect rare minerals from all over the country to create elixirs, including elixirs containing mercury, which inevitably posed health problems at high doses.

Legacy and death

After 45 years on the throne (the second longest reign in the Ming dynasty), the Jiajing Emperor died in 1567 – possibly due to mercury overdose from Chinese alchemical elixir poisoning – and was succeeded by his son, the Longqing Emperor. Though his long rule gave the dynasty an era of stability, the Jiajing Emperor's neglect of his official duties resulted in the decline of the dynasty at the end of the 16th century. His style of governance, or the lack thereof, would be emulated by his grandson later in the century.

The time when the Jiajing Emperor was buried was very close to the time of completion of the manuscript copy of the lost Yongle Encyclopedia. The Jiajing Emperor died in December 1566, but was buried three months later, in March 1567. One possibility is that they were waiting for the manuscript to be completed.

Portrayal in art

The Jiajing Emperor was portrayed in contemporary court portrait paintings, as well as in other works of art. For example, in this panoramic painting below, the Jiajing Emperor can be seen in the right half riding a black steed and wearing a plumed helmet. He is distinguished from his entourage of bodyguards as an abnormally tall figure.

Original – A panoramic painting showing the Jiajing Emperor travelling to the Ming tombs with a huge cavalry escort and an elephant-drawn carriage.

Original – A panoramic painting showing the Jiajing Emperor travelling to the Ming tombs with a huge cavalry escort and an elephant-drawn carriage.

Family

Consorts and Issue:

- Empress Xiaojiesu, of the Chen clan (1508–1528)

- miscarriage (1528)

- Deposed Empress, of the Zhang clan (d. 1537), personal name Zhang Qijie

- Empress Xiaolie, of the Fang clan (1516–1547)

- Empress Xiaoke, of the Du clan (d. 1554)

- Zhu Zaiji, the Longqing Emperor (4 March 1537 – 5 July 1572), third son

- Imperial Noble Consort Duanhegongrongshunwenxi, of the Wang clan (端和恭榮順溫僖皇貴妃 王氏; d. 1553)

- Zhu Zairui, Crown Prince Zhuangjing (1536–1549), second son

- Imperial Noble Consort Zhuangshunanrongzhenjing, of the Shen clan (莊順安榮貞靜皇貴妃 沈氏; d. 1581)

- Imperial Noble Consort Ronganhuishunduanxi, of the Yan clan (榮安惠順端僖皇貴妃 閻氏; d. 1541)

- Zhu Zaiji, Crown Prince Aichong (哀衝皇太子 朱載基; 7 September 1533 – 27 October 1533), first son

- Noble Consort Gongxizhenjing, of the Wen clan (恭僖貞靖 文氏)

- Noble Consort Rong'an, of the Ma clan (榮安貴妃 馬氏)

- Noble Consort, of the Zhou clan (貴妃 周氏; d. 1540)

- Consort Daoyingong, of the Wen clan (悼隱恭妃 文氏; d. 1532)

- Consort Duan, of the Cao clan (d. 1542)

- Zhu Shaoying, Princess Chang'an (常安公主 朱壽媖; 1536–1549), first daughter

- Zhu Luzheng, Princess Ning'an (寧安公主 朱祿媜; 1539–1607), third daughter

- Married Li He (李和) in 1555, and had issue (one son)

- Consort Huairongxian, of the Zheng clan (懷榮賢妃 鄭氏; d. 1536)

- Consort Jing, of the Lu clan (靖妃 盧氏; d. 1588)

- Zhu Zaizhen, Prince Gong of Jing (29 March 1537 – 9 February 1565), fourth son

- Consort Su, of the Jiang clan (肅妃 江氏)

- Zhu Zaishang, Prince Shang of Ying (潁殤王 朱載墒; 8 September 1537 – 9 September 1537), fifth son

- Consort Yi, of the Zhao clan (懿妃 趙氏; d. 1569)

- Zhu Zai, Prince Huai of Qi (戚懷王 朱載?; 1 October 1537 – 5 August 1538), sixth son

- Consort Yong, of the Chen clan (雍妃 陳氏; d. 1586)

- Zhu Zaikui, Prince Ai of Ji (薊哀王 朱載㙺; 29 January 1538 – 14 February 1538), seventh son

- Zhu Ruirong, Princess Guishan (歸善公主 朱瑞嬫; 1541–1544), fourth daughter

- Consort Hui, of the Wang clan (徽妃 王氏)

- Zhu Fuyuan, Princess Sirou (思柔公主 朱福媛; 1538–1549), second daughter

- Consort Rong, of the Zhao clan (榮妃 趙氏)

- Zhu Zaifeng, Prince Si of Jun (均思王 朱載堸; 23 August 1539 – 16 April 1540), eighth son

- Consort Rongzhaode, of the Zhang clan (榮昭德妃 張氏; d. 1574)

- Zhu Suzhen, Princess Jiashan (嘉善公主 朱素嫃; 1541–1564), fifth daughter

- Married Xu Congcheng (許從誠) in 1559

- Zhu Suzhen, Princess Jiashan (嘉善公主 朱素嫃; 1541–1564), fifth daughter

- Consort Rong'anzhen, of the Ma clan (榮安貞妃 馬氏; d. 1564)

- Consort Duanjingshu, of the Zhang clan (端靜淑妃 張氏)

- Consort Gongxili, of the Wang clan (恭僖麗妃 王氏; d. 1553)

- Consort Gongshurong, of the Yang clan (恭淑榮妃 楊氏; d. 1566)

- Consort Duanhuiyong, of the Xu clan (端惠永妃 徐氏)

- Concubine Ning, of the Wang clan (王宁嫔; d. 1542), head of the Renyin plot

Ancestry

| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (March 2022) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| Xuande Emperor (1399–1435) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Emperor Yingzong of Ming (1427–1464) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Empress Xiaogongzhang (1399–1462) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Chenghua Emperor (1447–1487) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Zhou Neng | |||||||||||||||||||

| Empress Xiaosu (1430–1504) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Lady Zhen | |||||||||||||||||||

| Zhu Youyuan (1476–1519) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Shao Yi | |||||||||||||||||||

| Shao Lin | |||||||||||||||||||

| Lady Peng | |||||||||||||||||||

| Empress Xiaohui (d. 1522) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Lady Yang | |||||||||||||||||||

| Jiajing Emperor (1507–1567) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Jiang Sheng | |||||||||||||||||||

| Jiang Xing | |||||||||||||||||||

| Jiang Xiao | |||||||||||||||||||

| Empress Cixiaoxian (d. 1538) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Lady Wu | |||||||||||||||||||

See also

Notes

- Zhu Junzhang was a descendant of Zhu Gui (1374–1446), the 13th son of the Hongwu Emperor, the first emperor of the Ming dynasty.

- Mencius used an analogy to justify King Wu's claim to the throne: King Wen, who was loyal to the Shang dynasty and virtuous, gained the favor of Heaven and his son was able to establish a new dynasty and restore proper governance.

- The delegation was led by Xu Guangzuo, Duke of Ding (a descendant of Xu Da); Zhang Heling, Marquis of Shouning and the younger brother of the Empress Dowager Zhang; the commandant-escort Cui Yuan, husband of the Chenghua Emperor's daughter; Grand Secretary Liang Chu; Minister of Rites Mao Cheng; and three highly ranked eunuchs.

- Previously, only the founder of the dynasty, the Hongwu Emperor, had a temple name ending in -zu (ancestor, founder), while the temple names of other emperors ended in -zong (ancestor).

- Already the first Ming emperor Hongwu (ruled 1368–1398), prayers to Confucius were banned in Buddhist and Taoist temples, and the use of name tablets in place of images was proposed. However, his decree was not enforced until before 1530.

- The Directorate of Ceremonial was the most influential of the eunuch offices of the Forbidden City, while the East Depot was the office of the eunuch secret police.

References

Citations

- ^ Geiss (1998), p. 440.

- ^ Goodrich & Fang (1976), p. 315.

- ^ Goodrich & Fang (1976), p. 316.

- ^ Geiss (1998), p. 441.

- Goodrich & Fang (1976), p. 308.

- ^ Geiss (1998), p. 442.

- Geiss (1998), p. 436.

- ^ Geiss (1990), pp. 37–51.

- ^ Dardess (2016), p. 7.

- Dardess (2016), p. 8.

- Geiss (1998), p. 443.

- Dardess (2016), p. 1.

- ^ Geiss (1998), pp. 444–445.

- Geiss (1998), pp. 446–447.

- Geiss (1998), p. 448.

- ^ Geiss (1998), p. 449.

- ^ Goodrich & Fang (1976), p. 317.

- ^ Wan (2009), p. 75.

- Fang (2014), p. 30.

- ^ Goodrich & Fang (1976), p. 320.

- ^ Geiss (1998), p. 457.

- Geiss (1998), p. 458.

- Geiss (1998), p. 465.

- Geiss (1998), p. 466.

- Geiss (1998), pp. 453–455.

- Geiss (1998), pp. 455–456.

- Geiss (1998), pp. 456–457.

- Geiss (1998), pp. 482–483.

- ^ Geiss (1998), p. 483.

- ^ Dardess (2016), p. 4.

- ^ Geiss (1998), p. 484.

- Geiss (1998), p. 485.

- Geiss (1998), p. 505.

- Geiss (1998), p. 507.

- ^ Dardess (2016), p. 3.

- Dardess (2016), p. 5.

- "Invasion of the Great Green Algae Monster Archived 2009-06-28 at the Wayback Machine. Salon. 25 Jun 2007.

- 一本书读懂大明史

- "China > History > The Ming dynasty > Political history > The dynastic succession", Encyclopædia Britannica Online, 2007

- "Beijing." Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 2007.

- "端妃曹氏与嘉靖宫变". Archived from the original on 7 September 2017. Retrieved 23 December 2010.

- "明廷"壬寅宫变"之谜". Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 23 December 2010.

- 萬曆野獲編, vol.18

- Zhang Tingyu, ed. (1739). "《明史》卷一百十四 列傳第二 后妃二" [History of Ming, Volume 114, Historical Biography 2, Empresses and Concubines 2]. Lishichunqiu Net (in Chinese). Lishi Chunqiu. Archived from the original on 14 October 2017. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- History Office, ed. (1620s). 明實錄:明世宗實錄 [Veritable Records of the Ming: Veritable Records of Shizong of Ming] (in Chinese). Vol. 406. Ctext.

- Lin, Guang (28 February 2017). "《永乐大典》 正本陪葬了嘉靖帝?". 《北京日报》. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

Works cited

- Dardess, John W (2016). Four Seasons: A Ming Emperor and His Grand Secretaries in Sixteenth-Century China. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9781442265608.

- Geiss, James (1990). "On the significance of the reign title Chia-ching". Ming Studies (1). doi:10.1179/014703790788763857.

- Geiss, James (1998). "The Chia-ching reign, 1522-1566". In Mote, Frederick W.; Twitchett, Denis C (eds.). The Cambridge History of China. Volume 7, The Ming Dynasty 1368-1644, Part 1 (1 ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 440–510. ISBN 0521243335.

- Goodrich, L. Carington; Fang, Chaoying (1976). Dictionary of Ming Biography, 1368-1644. Vol. 1, A–L. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-03801-1.

- Wan, Maggie C. K (2009). "Building an Immortal Land: The Ming Jiajing Emperor's West Park". Asia Major. Third Series. 22 (2): 65–99. ISSN 0021-9118.

- Fang, Jun (2014). China's Second Capital – Nanjing under the Ming, 1368-1644. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. ISBN 9780415855259.

- Li, Kangying (2010). The Ming Maritime Policy in Transition, 1367 to 1568. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz. ISBN 978-3-447-06172-8.

Further reading

- Fisher, Carney T. "Smallpox, Salesmen, and Sectarians: Ming-Mongol Relations in the Jiajing Reign (1522–67)." Ming Studies 1988.1 (1988): 1-23.

- Mote, F.W. Imperial China 900–1800 (1999) pp 660–72.

- Wan, Maggie CK. "Building an Immortal Land: The Ming Jiajing Emperor's West Park." Asia Major (2009): 65–99. online

- The Cambridge History of China, Vol. 7: The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644, Part I, "The Prince of Ning Treason" by Frederick W. Mote and Denis Twitchett.

- Huiping Pang, "The Confiscating Henchmen: The Masquerade of Ming Embroidered-Uniform Guard Liu Shouyou (ca. 1540-1604)," Ming Studies 72 (2015): 24–45. ISSN 0147-037X

| Jiajing Emperor House of ZhuBorn: 16 September 1507 Died: 23 January 1567 | ||

| Chinese royalty | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded byZhu Youyuan | Prince of Xing 1521 |

Merged into the Crown |

| Regnal titles | ||

| Preceded byZhengde Emperor | Emperor of the Ming dynasty Emperor of China 1521–1567 |

Succeeded byLongqing Emperor |

| Emperors of the Ming dynasty | ||

|---|---|---|

| Ming | 明 | |

| Southern Ming |

| |

| Xia → Shang → Zhou → Qin → Han → 3 Kingdoms → Jìn / 16 Kingdoms → S. Dynasties / N. Dynasties → Sui → Tang → 5 Dynasties & 10 Kingdoms → Liao / Song / W. Xia / Jīn → Yuan → Ming → Qing → ROC / PRC | ||