| Revision as of 08:27, 3 January 2025 editLEvalyn (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, New page reviewers5,375 edits removing uncited material from lead, expanding 'style' sectionTag: Visual edit← Previous edit | Revision as of 08:32, 3 January 2025 edit undoLEvalyn (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, New page reviewers5,375 edits →Major themes: adding an imageTags: nowiki added Visual editNext edit → | ||

| Line 51: | Line 51: | ||

| == Major themes == | == Major themes == | ||

| ] | |||

| ], skeptical of the disinterested moral virtue of self-styled "men of feeling"]] | |||

| === Fictionalized autobiography === | === Fictionalized autobiography === | ||

| When Sterne first became a literary celebrity through the success of ''Tristram Shandy'', he was frequently addressed as Tristram Shandy (or, in Paris, Chevalier Shandy), promoting an identification between himself and his novel's narrator.<ref name=":4" /> Over time, his career as a clergyman prompted him to be identified instead with a secondary character from ''Tristram Shandy'', Parson Yorick.<ref name=":4" /> In ''Tristram Shandy'', Parson Yorick is a melodramatically tragic figure: he is rejected by the church for his sense of humour, and dies of a broken heart. The novel 'mourns' him by presenting his epitaph ("Alas, poor YORICK!") and printing a page of solid black.<ref name=":4" /> Parson Yorick's unsuccessful clerical career mirrored Sterne's provincial obscurity as a clergyman before ''Tristram Shandy''.<ref name=":4" /> | When Sterne first became a literary celebrity through the success of ''Tristram Shandy'', he was frequently addressed as Tristram Shandy (or, in Paris, Chevalier Shandy), promoting an identification between himself and his novel's narrator.<ref name=":4" /> Over time, his career as a clergyman prompted him to be identified instead with a secondary character from ''Tristram Shandy'', Parson Yorick.<ref name=":4" /> In ''Tristram Shandy'', Parson Yorick is a melodramatically tragic figure: he is rejected by the church for his sense of humour, and dies of a broken heart. The novel 'mourns' him by presenting his epitaph ("Alas, poor YORICK!") and printing a page of solid black.<ref name=":4" /> Parson Yorick's unsuccessful clerical career mirrored Sterne's provincial obscurity as a clergyman before ''Tristram Shandy''.<ref name=":4" /> | ||

| Sterne reinforced his public identification with Yorick when he published a collection of his own sermons under the title ''The Sermons of Mr. Yorick''. Two volumes appeared in 1760, and two more in 1766.<ref name=":4" /> | Sterne reinforced his public identification with Yorick when he published a collection of his own sermons under the title ''The Sermons of Mr. Yorick''. Two volumes appeared in 1760, and two more in 1766.<ref name=":4" />], skeptical of the disinterested moral virtue of self-styled "men of feeling"]] | ||

| === Potential for satire === | === Potential for satire === | ||

Revision as of 08:32, 3 January 2025

1768 novel by Laurence Sterne

Title page from Vol. I of the 1768 first edition. Title page from Vol. I of the 1768 first edition. | |

| Author | Laurence Sterne |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | sentimental novel, travel literature |

| Publisher | T. Becket and P. A. De Hondt |

| Publication date | 1768 |

| Publication place | Great Britain |

| Media type | Print, 12mo |

| Pages | 283, in two volumes |

| Dewey Decimal | 823.6 |

A Sentimental Journey Through France and Italy is a novel by Laurence Sterne, written and first published in 1768, as Sterne was facing death. In 1765, Sterne travelled through France and Italy as far south as Naples, and after returning, he determined to describe his travels from a sentimental point of view. The narrator is the Reverend Mr. Yorick, a character from his bestselling previous novel Tristram Shandy who also serves as Sterne's barely disguised alter ego. The book recounts his various adventures, usually of the amorous type, in a series of self-contained episodes. The book is less eccentric and more elegant in style than Tristram Shandy and was better received by contemporary critics.

Plot summary

Yorick's journey starts in Calais, where he meets a monk who begs for donations to his convent. Yorick initially refuses to give him anything, but later regrets his decision. He and the monk exchange their snuff-boxes. He buys a chaise to continue his journey. The next town he visits is Montreuil, where he hires a servant to accompany him on his journey, a young man named La Fleur.

During his stay in Paris, Yorick is informed that the police inquired for his passport at his hotel. Without a passport at a time when England is at war with France (Sterne travelled to Paris in January 1762, before the Seven Years' War ended), he risks imprisonment in the Bastille. Yorick decides to travel to Versailles, where he visits the Count de B**** to acquire a passport. When Yorick notices the count reads Hamlet, he points with his finger at Yorick's name, mentioning that he is Yorick. The count mistakes him for the king's jester and quickly procures him a passport. Yorick fails in his attempt to correct the count, and remains satisfied with receiving his passport so quickly.

Yorick returns to Paris, and continues his voyage to Italy after staying in Paris for a few more days. Along the way he decides to visit Maria—who was introduced in Sterne's previous novel, Tristram Shandy—in Moulins. Maria's mother tells Yorick that Maria has been struck with grief since her husband died. Yorick consoles Maria, and then leaves.

After having passed Lyon during his journey, Yorick spends the night in a roadside inn. Because there is only one bedroom, he is forced to share the room with a lady and her chamber-maid ("fille de chambre"). When Yorick can't sleep and accidentally breaks his promise to remain silent during the night, an altercation with the lady ensues. During the confusion, Yorick accidentally grabs hold of something belonging to the chamber-maid. The last line is: "when I stretch'd out my hand I caught hold of the fille de chambre's... End of vol II". The sentence is open to interpretation. You can say the last word is omitted, or that he stretched out his hand, and caught hers (this would be grammatically correct). Another interpretation is to incorporate "End of Vol. II" into the sentence, so that he grabs the Fille de Chambre's 'End'.

Style

The language of A Sentimental Journey is playful, with an interest in puns, especially sexual double entendres.

A Sentimental Journey is picaresque in its meandering series of disconnected adventures on the road. It is also quixotic in its hero's over-attachment to a misguided ideal. Structurally, the novel moves between tableaux-like scenes with little information about the links between them, often omitting explanations of how Yorick actually travelled along his journey.

In the 1760s, travel writing was a more popular and respected literary genre than the novel, undergoing a popularizing shift. Travel writing like Joseph Addison's earlier Remarks on several parts of Italy, &c., in the years 1701, 1702, 1703 were regarded as overly focused on classical scholarship, which was uninteresting and inaccessible to middle-class audiences. To better entertain their readers, travel writers began to emphasize personal anecdotes over scholarship or practical guidebook catalogues, and each writer sought to cultivate a distinctive narrative voice. Travel narratives were rarely written by the small elite of aristocratic young men who went on a formal Grand Tour; instead, they were written by more middle-class travellers, whose journeys might have practical motivation. Many stylistic aspects of A Sentimental Journey simply take these trends to their logical extreme. A Sentimental Journey can also be seen as an answer to Tobias Smollett's decidedly unsentimental Travels Through France and Italy. Sterne had met Smollett during his travels in Europe, and strongly objected to his spleen, acerbity and quarrelsomeness. He modelled the character of Smelfungus on Smollett.

Composition and publication

Before A Sentimental Journey, Sterne had been publishing the novel Tristram Shandy in installments since 1762. That novel was most praised for its sentimentality, with some reviewers suggesting that Sterne was better at writing pathos than humour. The general literary taste also grew more disapproving of lewd content in the 1760s. In 1765, Ralph Griffiths reviewed the latest volumes of Tristram Shandy by saying that the public was no longer interested in that novel, directly advising Sterne to begin a new one focused on sentimentality. Griffiths later took credit for the publication of A Sentimental Journey, which he praised.

Sterne travelled to France and Italy several times in the 1760s, which inspired a parodic account of the Grand Tour in volume 7 of Tristram Shandy in 1765. Still inspired, he decided to write a new book which would experiment with the genre of the travel narrative, and revive his literary reputation after the declining sales of Tristram Shandy.

Sterne wrote to his daughter about the new project in February of 1767. By June 1767, he was working seriously on it, with particular efforts in November and December. During the process of composition, Sterne frequently exchanged passionate letters with a married woman, Elizabeth Draper. These letters and his novel both express intense, frustrated desire. He signed all his letters to her as "Yorick". (These letters would later be published as Letters to Eliza, also sometimes called Journal to Eliza, in 1773.) Volumes 1 and 2 of A Sentimental Journey were published on February 27, 1768. The novel was planned as a four-volume work, but only the first two were published due to Sterne's death in 1768.

A Sentimental Journey was rapidly and widely translated on its publication. German and French editions appeared the same year as the English, and by the early 1800s it had been translated into seven other European languages.

Reception

At its publication, A Sentimental Journey was reviewed as a travel narrative rather than a novel, and well-received for its fresh contributions to that genre. From Sterne's death through the nineteenth century, A Sentimental Journey was considered Sterne's best and most beloved work, and it was more widely reprinted than Tristram Shandy. Eighteenth-century readers preferred it to Tristram Shandy, partly because it was less obviously sexual. Its positive reputation was particularly promoted by the volume of extracts, The Beauties of Sterne, which was compiled by William Holland in 1782 and included many passages praised for their emotional power. The Beauties of Sterne went through twelve editions in ten years.

By the mid-nineteenth century, the novel's reception grew more mixed, as Victorian readers were less tolerant of its 'indecencies'. William Makepeace Thackeray influentially criticized its "corruption," though some of his contemporaries resisted this assessment. Leslie Stephen also objected to Sterne's double entendres. In the early twentieth century, Virginia Woolf promoted a rejection of Victorian mores through her highly admiring introduction to a 1928 edition of the novel. As others followed suit in embracing Sterne's proto-modernist experimentation with form, A Sentimental Journey began to be overshadowed for the first time by Tristram Shandy, which attracted scholarly attention for its more daring experiments in literary form. Today, A Sentimental Journey is studied for its role in the broader phenomenon of eighteenth century sensibility.

Major themes

Fictionalized autobiography

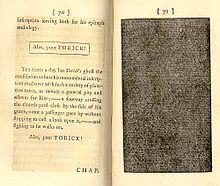

When Sterne first became a literary celebrity through the success of Tristram Shandy, he was frequently addressed as Tristram Shandy (or, in Paris, Chevalier Shandy), promoting an identification between himself and his novel's narrator. Over time, his career as a clergyman prompted him to be identified instead with a secondary character from Tristram Shandy, Parson Yorick. In Tristram Shandy, Parson Yorick is a melodramatically tragic figure: he is rejected by the church for his sense of humour, and dies of a broken heart. The novel 'mourns' him by presenting his epitaph ("Alas, poor YORICK!") and printing a page of solid black. Parson Yorick's unsuccessful clerical career mirrored Sterne's provincial obscurity as a clergyman before Tristram Shandy.

Sterne reinforced his public identification with Yorick when he published a collection of his own sermons under the title The Sermons of Mr. Yorick. Two volumes appeared in 1760, and two more in 1766.

Potential for satire

From Sterne's day to the present, readers have debated how seriously to take the novel's expressions of sentimental emotion. Eighteenth-century skeptics of the sentimental movement questioned the sincerity and disinteredness of those who promoted "feeling" as a new moral code. They particularly criticized the shallowness of moments where Yorick expresses emotion but takes no action. Several twentieth-century scholars have argued that Yorick's feelings and religious expressions are intentionally excessive, and that he ought to be read as an unreliable narrator. In treating the novel as a satirical one, they emphasize the many humorous scenes. Thomas Keymer argues in The Cambridge Companion to Laurence Sterne that the novel is best understood as offering the reader both options, serious or satirical, depending on their tastes.

Legacy

Illustrations

A Sentimental Journey inspired a large number of illustrations, in the form of paintings, prints for sale, and decorated merchandise. Images of "Poor Maria," for example, were particularly popular. Angelica Kauffmann painted Poor Maria in 1777, and printed copies were sold throughout Europe. The porcelain company Wedgwood created cameos of a similar "Poor Maria" image (and its companion shepherd portrait, the "Bourbonnais Shepherd") to decorate a wide range of products. This best-selling motif appeared on personal adornments like brooches and shoe buckles, as well as household goods like teaware and vases. The design was used on jasperware bud vases as late as the 1960s.

Other popular scenes for illustration were Yorick and the grisette, and the captive. Joseph Wright of Derby made four paintings based on A Sentimental Journey: one version of "The Captive" in 1774, another "The Captive" and a portrait of Maria in 1771, and a second portrait of Maria in 1781.

Books written in response

Beginning in 1769, several "continuations" of A Sentimental Journey were published, many of which claimed to be by Sterne. One continuation has often been attributed to Sterne's long-time friend John Hall-Stevenson, who is identified with the character Eugenius in the novel. It is titled Yorick's Sentimental Journey Continued: To Which Is Prefixed Some Account of the Life and Writings of Mr. Sterne (1769), and was sometimes bound with Sterne's real volumes to produce an apparently complete work. Another continuation, also published in 1769, "consisted largely of sexually titillating anecdotes about nuns."

In 1789, A Sentimental Journey was parodied by the anonymous novel A Man of Failing, which also targeted Henry Mackenzie's The Man of Feeling.

In the 1880s, American writer Elizabeth Robins Pennell and her artist husband Joseph Pennell undertook a journey following Sterne's route. Their travels by tandem bicycle were turned into the book Our sentimental journey through France and Italy (1888).

Viktor Shklovsky considered Sterne one of his most important precursors as a writer, and his own A Sentimental Journey: Memoirs, 1917–1922 was indebted to both Sterne's own Sentimental Journey and Tristram Shandy.

Footnotes

- Sterne, Laurence (2008). Jack, Ian; Parnell, Tim (eds.). A Sentimental Journey and Other Writings. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 236. ISBN 978-0-19-953718-1.

- ^ "A Sentimental Journey through France and Italy". Literary Encyclopedia. Retrieved 3 January 2025.

- ^ Turner, Katherine (25 August 2010). "Introduction". A Sentimental Journey through France and Italy. Broadview Press. ISBN 978-1-77048-701-7.

- Head, Dominic, ed. (2006). "Travels through France and Italy". The Cambridge Guide to Literature in English (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 1124.

- ^ Keymer, Thomas (20 August 2009). "A Sentimental Journey and the failure of feeling". The Cambridge Companion to Laurence Sterne. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-82756-0.

- ^ Owens, William James (1994). The evolution of Sterne's "A Sentimental Journey" (Ph.D. thesis). University of Virginia.

- ^ "Poor Maria and the Bourbonnais Shepherd – when literature came into fashion · V&A". Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 3 January 2025.

- "The sentimental side of Angelica Kauffman". Apollo Magazine. 1 March 2024. Retrieved 3 January 2025.

- "Maria". The British Museum. Archived from the original on 26 September 2024. Retrieved 3 January 2025.

- "Wedgwood Jasperware Blue Bud Vase". The Magpie. Retrieved 3 January 2025.

- Sterne, Laurence (2008). Jack, Ian; Parnell, Tim (eds.). A Sentimental Journey and Other Writings. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 233. ISBN 978-0-19-953718-1.

- "Sterne and Sterneana : Yorick's sentimental journey, continued to which is prefixed, some account of the life and writings of Mr. Sterne Vol. 3". Cambridge Digital Library. Retrieved 3 January 2025.

- Richard Sheldon, intro. to Shklovsky, A Sentimental Journey: Memoirs, 1917–1922 (Dalkey Archive Press, 2004: ISBN 1564783545), p. xvi.

External links

- A Sentimental Journey Through France and Italy, Literature in Context: An Open Anthology of Literature. 2021. Web.

- A Sentimental Journey Through France and Italy at Project Gutenberg

- A Sentimental Journey Through France and Italy public domain audiobook at LibriVox

- Editions of A Sentimental Journey held by the Laurence Sterne Trust

- Images from an 1875 French edition extra-illustrated with watercolors in the margins by Louis Émile Benassit

| Laurence Sterne | |

|---|---|

| Works |

|

| Adaptations | |

| Miscellaneous | |