| Revision as of 17:02, 2 January 2025 edit2a02:8308:b102:a00:19bf:180c:834f:9baa (talk) →Design← Previous edit | Revision as of 00:21, 6 January 2025 edit undo2601:4c4:c17f:b130:851b:a73a:859f:3810 (talk) I'm retired final editTag: RevertedNext edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{ |

{{short description|Siege engine originating in ancient times}} | ||

| {{Other uses|Battering Ram (disambiguation)}} | {{Other uses|Battering Ram (disambiguation)}} | ||

| {{More citations needed|date=February 2008}} | {{More citations needed|date=February 2008}} | ||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

| Rams proved effective weapons of war because at the time wall-building materials such as stone and brick were weak in ], and therefore prone to cracking when impacted with force. With repeated blows, the cracks would grow steadily until a hole was created. Eventually, a breach would appear in the fabric of the wall, enabling armed attackers to force their way through the gap and engage the inhabitants of the citadel. | Rams proved effective weapons of war because at the time wall-building materials such as stone and brick were weak in ], and therefore prone to cracking when impacted with force. With repeated blows, the cracks would grow steadily until a hole was created. Eventually, a breach would appear in the fabric of the wall, enabling armed attackers to force their way through the gap and engage the inhabitants of the citadel. | ||

| The introduction in the later ] of siege ]s, which harnessed the explosive power of ] to propel weighty stone or iron balls against fortified obstacles, spelled the end of battering rams and other traditional siege weapons. Smaller, hand-held versions of battering rams are still used today by law enforcement officers and military personnel to |

The introduction in the later ] of siege ]s, which harnessed the explosive power of ] to propel weighty stone or iron balls against fortified obstacles, spelled the end of battering rams and other traditional siege weapons. Smaller, hand-held versions of battering rams are still used today by law enforcement officers and military personnel to knock down doors.<ref>Hey mama did you hear that? There’s a man going down to the courthouse as fast as he can and he’s coming back with this big huge thing that knocks down doors eeeeeee!!!What are yall going on about in here?Mama was talking with the man from the cops he had dis big huge thang and he was knocking down doors ah goo | ||

| </ref> | |||

| A '''capped ram''' is a battering ram that has an accessory at the head (usually made of iron or steel and sometimes punningly shaped into the head and horns of an ]) to do more damage to a building. It was much more effective at destroying enemy walls and buildings than an uncapped ram but was heavier to carry. | A '''capped ram''' is a battering ram that has an accessory at the head (usually made of iron or steel and sometimes punningly shaped into the head and horns of an ]) to do more damage to a building. It was much more effective at destroying enemy walls and buildings than an uncapped ram but was heavier to carry. | ||

| Line 16: | Line 17: | ||

| ==Design== | ==Design== | ||

| The earliest depiction of a possible battering ram is from the tomb of the ] |

The earliest depiction of a possible battering ram is from the tomb of the ] noble Khety, where a pair of soldiers advance towards a fortress under the protection of a mobile roofed structure, carrying a long pole that may represent a simple battering ram.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.touregypt.net/featurestories/siegewarfare.html| title=Siege warfare in ancient Egypt |publisher=Tour Egypt|access-date=23 May 2020 |quote=...we find a pair of Middle Kingdom soldiers advancing towards a fortress under the protection of a mobile roofed structure. They carry a long pole that was perhaps an early battering ram. }}</ref> | ||

| During the ], in the ancient Middle East and Mediterranean, the battering ram's log was slung from a wheeled frame by ropes or chains so that it could be made more massive and be more easily bashed against its target. Frequently, the ram's point would be reinforced with a metal head or cap while vulnerable parts of the shaft were bound with strengthening metal bands. ] details in his text |

During the ], in the ancient Middle East and Mediterranean, the battering ram's log was slung from a wheeled frame by ropes or chains so that it could be made more massive and be more easily bashed against its target. Frequently, the ram's point would be reinforced with a metal head or cap while vulnerable parts of the shaft were bound with strengthening metal bands.BO! ] details in his text '']'' that Ceras the ] was the first to make a ram with a wooden base with wheels and a wooden superstructure, with the ram hung within. This structure moved so slowly, however, that he called it the ''testudo'' (Latin for "tortoise").<ref>Humphrey, John W. Oleson, John P. Sherwood, Andrew N. "Greek and Roman Technology: A Sourcebook". Routledge, 1998, p. 565.</ref> | ||

| Another type of ram was one that maintained the normal shape and structure, but the support beams were instead made of saplings that were lashed together. The frame was then covered in hides as normal to defend from fire. The only solid beam present was the ram that was hung from the frame. The frame itself was so light that it could be carried on the shoulders of the men transporting the ram, and the same men could beat the ram against the wall when they reached it.<ref>Humphrey, John W. Oleson, John P. Sherwood, Andrew N. "Greek and Roman Technology: A Sourcebook". Routledge, 1998, p. 566.</ref> | Another type of ram was one that maintained the normal shape and structure, but the support beams were instead made of saplings that were lashed together. The frame was then covered in hides as normal to defend from fire. The only solid beam present was the ram that was hung from the frame. The frame itself was so light that it could be carried on the shoulders of the men transporting the ram, and the same men could beat the ram against the wall when they reached it.<ref>Humphrey, John W. Oleson, John P. Sherwood, Andrew N. "Greek and Roman Technology: A Sourcebook". Routledge, 1998, p. 566.</ref> | ||

| Many battering rams had curved or slanted wooden roofs and side-screens, covered in protective materials, usually fresh wet hides. These canopies reduced the risk of the ram being set on fire, and protected the operators of the ram from arrow and |

Many battering rams had curved or slanted wooden roofs and side-screens, covered in protective materials, usually fresh wet hides. These canopies reduced the risk of the ram being set on fire, and protected the operators of the ram from arrow and spear volleys launched from above. | ||

| An image of an ]n battering ram depicts how sophisticated attacking and defensive practices had become by the 9th century BC. The defenders of a town wall are trying to set the ram alight with torches and have also put a chain under it. The attackers are trying to pull on the chain to free the ram, while the aforementioned wet hides on the canopy provide protection against the flames. | An image of an ]n battering ram depicts how sophisticated attacking and defensive practices had become by the 9th century BC. The defenders of a town wall are trying to set the ram alight with torches and have also put a chain under it. The attackers are trying to pull on the chain to free the ram, while the aforementioned wet hides on the canopy provide protection against the flames. | ||

| By the time the ] made their incursions into Egypt, |

By the time the ] made their incursions into Egypt, around 715 BC, walls, siege tactics and equipment had undergone many changes. Early shelters protecting ] armed with poles trying to breach ] ramparts gave way to battering rams.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.touregypt.net/featurestories/siegewarfare.html| title=Siege warfare in ancient Egypt |publisher=Tour Egypt|access-date=23 May 2020}}</ref> | ||

| The first confirmed use of rams in the Occident happened from 503 to 502 BC when Opiter ] became consul of the Romans during the fight against Aurunci people: | The first confirmed use of rams in the Occident happened from 503 to 502 BC when Opiter ] became consul of the Romans during the fight against Aurunci people: | ||

| {{ |

{{Quote|text=The following consuls, Opiter Virginius and Sp. Cassius, first endeavored to take Pometia by storm, and afterwards by raising battering rams (vineae) and other works.|author=], Ab urbe condita, History of Rome, Book II, Chapter 17}} | ||

| The second known use was in 427 BC, when the ]ns besieged ].<ref>Tucidides, II, 76.</ref> The first use of rams within the Mediterranean Basin, featuring in this case the simultaneous employment of ] to shelter the rammers from attack, occurred on the island of ] in 409 BC, at the ] siege.<ref>Diodorus the Siculus, XIII, 43-62.</ref> | The second known use was in 427 BC, when the ]ns besieged ].<ref>Tucidides, II, 76.</ref> The first use of rams within the Mediterranean Basin, featuring in this case the simultaneous employment of ] to shelter the rammers from attack, occurred on the island of ] in 409 BC, at the ] siege.<ref>Diodorus the Siculus, XIII, 43-62.</ref> | ||

| Line 48: | Line 49: | ||

| There is a popular myth in ], England that the well known children's rhyme, ], is about a battering ram used in the siege of Gloucester in 1643, during the ]. However, the story is almost certainly untrue; during the siege, which lasted only one month, no battering rams were used, although many cannons were. The idea seems to have originated in a spoof history essay by Professor David Daube written for '']'' in 1956, which was widely believed despite obvious improbabilities (e.g., planning to cross the ] by running the ram down a hill at speed, although the river is about 30 m (100 feet) wide at this point). | There is a popular myth in ], England that the well known children's rhyme, ], is about a battering ram used in the siege of Gloucester in 1643, during the ]. However, the story is almost certainly untrue; during the siege, which lasted only one month, no battering rams were used, although many cannons were. The idea seems to have originated in a spoof history essay by Professor David Daube written for '']'' in 1956, which was widely believed despite obvious improbabilities (e.g., planning to cross the ] by running the ram down a hill at speed, although the river is about 30 m (100 feet) wide at this point). | ||

| ==Use in mining== | |||

| ] in his '']'' describes a battering ram used in mining, where hard rock needed to be broken down to release the ]. The pole possessed a metal tip weighing 150 pounds, so the whole device will have weighed at least twice as much in order to preserve its balance. Whether or not it was supported by being suspended with ropes from a frame remains unknown, but very likely given its total weight. Such devices were used during coal mining in the 19th century in Great Britain before the widespread use of explosives, which were expensive and dangerous to use in practice. | |||

| == Modern use == | == Modern use == | ||

| ] | ] | ||

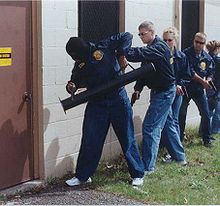

| Battering rams still have a use in modern times. Police forces often employ small, one-man or two-man metal rams, known as ], for forcing open locked portals or effecting a ]. Modern battering rams sometimes incorporate a ] |

Battering rams still have a use in modern times. Police forces often employ small, one-man or two-man metal rams, known as ], for forcing open locked portals or effecting a ]. Modern battering rams sometimes incorporate a ], along the length of which a ] fires automatically upon striking a hard object, thus enhancing the ] of the impact significantly.<ref>{{cite patent | ||

| | country = US | | country = US | ||

| | number = 2009199613 | | number = 2009199613 | ||

| Line 59: | Line 63: | ||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| *] | |||

| *] – In military aviation, deliberately causing a ] to attack an opposing aircraft | |||

| *] | *] | ||

| *] | *] | ||

| *] | |||

| *] – A battering ram-like device fitted to naval vessels, used to attack, disable and/or sink enemy ships | |||

| *] – various military and civil tactics | *] – various military and civil tactics | ||

| *] – using a vehicle as an improvised battering ram to gain access to a building for the purpose of ] | *] – using a vehicle as an improvised battering ram to gain access to a building for the purpose of ] | ||

| Line 70: | Line 74: | ||

| ==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| {{commons category |

{{commons category inline}} | ||

| *{{Cite NSRW|wstitle=Battering Ram|short=x}} | *{{Cite NSRW|wstitle=Battering Ram|short=x}} | ||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Battering Ram}} | {{DEFAULTSORT:Battering Ram}} | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

Revision as of 00:21, 6 January 2025

Siege engine originating in ancient times For other uses, see Battering Ram (disambiguation).| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Battering ram" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (February 2008) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

A battering ram is a siege engine that originated in ancient times and was designed to break open the masonry walls of fortifications or splinter their wooden gates. In its simplest form, a battering ram is just a large, heavy log carried by several people and propelled with force against an obstacle; the ram would be sufficient to damage the target if the log were massive enough and/or it were moved quickly enough (that is, if it had enough momentum). Later rams encased the log in an arrow-proof, fire-resistant canopy mounted on wheels. Inside the canopy, the log was swung from suspensory chains or ropes.

Rams proved effective weapons of war because at the time wall-building materials such as stone and brick were weak in tension, and therefore prone to cracking when impacted with force. With repeated blows, the cracks would grow steadily until a hole was created. Eventually, a breach would appear in the fabric of the wall, enabling armed attackers to force their way through the gap and engage the inhabitants of the citadel.

The introduction in the later Middle Ages of siege cannons, which harnessed the explosive power of gunpowder to propel weighty stone or iron balls against fortified obstacles, spelled the end of battering rams and other traditional siege weapons. Smaller, hand-held versions of battering rams are still used today by law enforcement officers and military personnel to knock down doors.

A capped ram is a battering ram that has an accessory at the head (usually made of iron or steel and sometimes punningly shaped into the head and horns of an ovine ram) to do more damage to a building. It was much more effective at destroying enemy walls and buildings than an uncapped ram but was heavier to carry.

Design

The earliest depiction of a possible battering ram is from the tomb of the 11th Dynasty noble Khety, where a pair of soldiers advance towards a fortress under the protection of a mobile roofed structure, carrying a long pole that may represent a simple battering ram.

During the Iron Age, in the ancient Middle East and Mediterranean, the battering ram's log was slung from a wheeled frame by ropes or chains so that it could be made more massive and be more easily bashed against its target. Frequently, the ram's point would be reinforced with a metal head or cap while vulnerable parts of the shaft were bound with strengthening metal bands.BO! Vitruvius details in his text De architectura that Ceras the Carthaginian was the first to make a ram with a wooden base with wheels and a wooden superstructure, with the ram hung within. This structure moved so slowly, however, that he called it the testudo (Latin for "tortoise").

Another type of ram was one that maintained the normal shape and structure, but the support beams were instead made of saplings that were lashed together. The frame was then covered in hides as normal to defend from fire. The only solid beam present was the ram that was hung from the frame. The frame itself was so light that it could be carried on the shoulders of the men transporting the ram, and the same men could beat the ram against the wall when they reached it.

Many battering rams had curved or slanted wooden roofs and side-screens, covered in protective materials, usually fresh wet hides. These canopies reduced the risk of the ram being set on fire, and protected the operators of the ram from arrow and spear volleys launched from above.

An image of an Assyrian battering ram depicts how sophisticated attacking and defensive practices had become by the 9th century BC. The defenders of a town wall are trying to set the ram alight with torches and have also put a chain under it. The attackers are trying to pull on the chain to free the ram, while the aforementioned wet hides on the canopy provide protection against the flames.

By the time the Kushites made their incursions into Egypt, around 715 BC, walls, siege tactics and equipment had undergone many changes. Early shelters protecting sappers armed with poles trying to breach mudbrick ramparts gave way to battering rams.

The first confirmed use of rams in the Occident happened from 503 to 502 BC when Opiter Verginius became consul of the Romans during the fight against Aurunci people:

The following consuls, Opiter Virginius and Sp. Cassius, first endeavored to take Pometia by storm, and afterwards by raising battering rams (vineae) and other works.

— Livy, Ab urbe condita, History of Rome, Book II, Chapter 17

The second known use was in 427 BC, when the Spartans besieged Plataea. The first use of rams within the Mediterranean Basin, featuring in this case the simultaneous employment of siege towers to shelter the rammers from attack, occurred on the island of Sicily in 409 BC, at the Selinus siege.

Defenders manning castles, forts or bastions would sometimes try to foil battering rams by dropping obstacles in front of the ram, such as a large sack of sawdust, just before the ram's head struck a wall or gate, or by using grappling hooks to immobilize the ram's log. Alternatively, the ram could be set ablaze, doused in fire-heated sand, pounded by boulders dropped from battlements or invested by a rapid sally of troops.

Some battering rams were not slung from ropes or chains, but were instead supported by rollers. This allowed the ram to achieve a greater speed before striking its target, making it more destructive. Such a ram, as used by Alexander the Great, is described by Vitruvius.

Alternatives to the battering ram included the drill, the sapper's mouse, the pick, the siege hook, and the hunting ram. These devices were smaller than a ram and could be used in confined spaces.

Notable sieges

Battering rams had an important effect on the evolution of defensive walls, which were constructed ever more ingeniously in a bid to nullify the effects of siege engines. Historical instances of the usage of battering rams in sieges of major cities include:

- The destruction of Jerusalem by the Romans

- The Crusades

- The Sack of Rome (410)

- The various sieges of Constantinople

There is a popular myth in Gloucester, England that the well known children's rhyme, Humpty Dumpty, is about a battering ram used in the siege of Gloucester in 1643, during the Civil War. However, the story is almost certainly untrue; during the siege, which lasted only one month, no battering rams were used, although many cannons were. The idea seems to have originated in a spoof history essay by Professor David Daube written for The Oxford Magazine in 1956, which was widely believed despite obvious improbabilities (e.g., planning to cross the River Severn by running the ram down a hill at speed, although the river is about 30 m (100 feet) wide at this point).

Use in mining

Pliny the Elder in his Naturalis historia describes a battering ram used in mining, where hard rock needed to be broken down to release the ore. The pole possessed a metal tip weighing 150 pounds, so the whole device will have weighed at least twice as much in order to preserve its balance. Whether or not it was supported by being suspended with ropes from a frame remains unknown, but very likely given its total weight. Such devices were used during coal mining in the 19th century in Great Britain before the widespread use of explosives, which were expensive and dangerous to use in practice.

Modern use

Battering rams still have a use in modern times. Police forces often employ small, one-man or two-man metal rams, known as enforcers, for forcing open locked portals or effecting a door breaching. Modern battering rams sometimes incorporate a cylinder, along the length of which a piston fires automatically upon striking a hard object, thus enhancing the momentum of the impact significantly.

See also

- Aerial ramming

- Impact (mechanics)

- List of siege engines

- Naval ram

- Ramming – various military and civil tactics

- Ram-raiding – using a vehicle as an improvised battering ram to gain access to a building for the purpose of breaking and entering

Notes

- Hey mama did you hear that? There’s a man going down to the courthouse as fast as he can and he’s coming back with this big huge thing that knocks down doors eeeeeee!!!What are yall going on about in here?Mama was talking with the man from the cops he had dis big huge thang and he was knocking down doors ah goo

- "Siege warfare in ancient Egypt". Tour Egypt. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

...we find a pair of Middle Kingdom soldiers advancing towards a fortress under the protection of a mobile roofed structure. They carry a long pole that was perhaps an early battering ram.

- Humphrey, John W. Oleson, John P. Sherwood, Andrew N. "Greek and Roman Technology: A Sourcebook". Routledge, 1998, p. 565.

- Humphrey, John W. Oleson, John P. Sherwood, Andrew N. "Greek and Roman Technology: A Sourcebook". Routledge, 1998, p. 566.

- "Siege warfare in ancient Egypt". Tour Egypt. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- Tucidides, II, 76.

- Diodorus the Siculus, XIII, 43-62.

- US Abandoned 2009199613, "Battering ram"

External links

![]() Media related to Battering rams at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Battering rams at Wikimedia Commons