| Revision as of 21:40, 21 May 2005 view sourceSlrubenstein (talk | contribs)30,655 editsm Reverted edits by Smoddy to last version by Noerouz← Previous edit | Revision as of 23:53, 21 May 2005 view source FlavrSavr (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users8,347 editsm + mkNext edit → | ||

| Line 284: | Line 284: | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

Revision as of 23:53, 21 May 2005

|

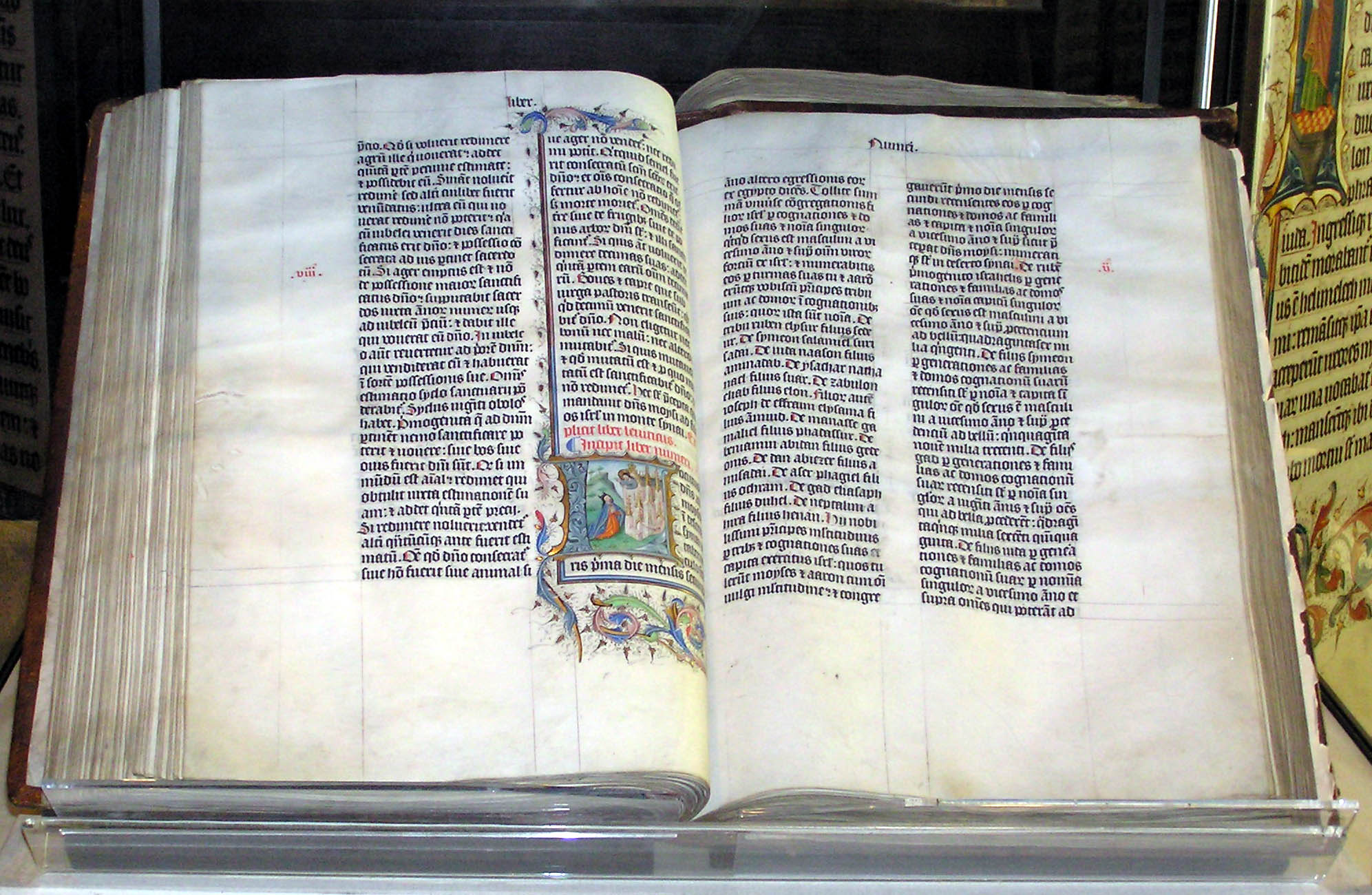

The Bible (From Greek (τα) βιβλια, (ta) biblia, "(the) books", plural of βιβλιον, biblion, "book", originally a diminutive of βιβλος, biblos, which in turn is derived from βυβλος—byblos, meaning "papyrus", from the ancient Phoenician city of Byblos which exported this writing material), is a word applied to sacred scriptures.

Although most often used of Jewish and Christian scriptures, "Bible" is sometimes used to describe scriptures of other faiths; thus the Guru Granth Sahib is often referred to as the "Sikh Bible".

Contents

As the original meaning of the word indicates, Jewish and Christian Bibles are actually collections of several books, considered to be inspired by God or to record God's relationship with humanity or a particular nation.

The Jewish Bible (Tanakh) consists of 24 books, and to a large extent overlaps with the contents of the Christian Old Testament, but with the books differently ordered. The Tanakh consists of the five books of Moses (the Torah or Pentateuch), a section called "Prophets" (Nevi'im), and a third section called "Writings" (Ketuvim or Hagiographa). The term "Tanakh" is a Hebrew acronym formed from these three names. Although the Tanakh was mainly written in Biblical Hebrew, it has some portions in Biblical Aramaic.

Some time in the 3rd century BCE, the Torah was translated into Koine Greek, and over the next century other books were translated as well. This translation became known as the Septuagint and was widely used by Greek-speaking Jews and, later, by Christians. It differs somewhat from the Hebrew text as standardized later (Masoretic Text), and was generally abandoned, in favour of the latter, as the basis for translations into Western languages from Saint Jerome 's Vulgate to the present day. In Eastern Christianity, translations based on the Septuagint still prevail. Some modern Western translations make use of the Septuagint to clarify passages in the Masoretic Text that seem to have suffered corruption in transcription. They also sometimes adopt variants that appear in texts discovered among the Dead Sea Scrolls. (For more information, see the entry on Bible translations).

The collection of books that the great majority of Christians (including members of the Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, and Oriental Orthodox Churches) call the Old Testament include not only the 24 books of the Jewish Tanakh, but also certain deuterocanonical books preserved in the Greek of the Septuagint. The Roman Catholic Church recognizes seven such books (Tobit, Judith, 1 Maccabees, 2 Maccabees, Wisdom of Solomon, Sirach (Ecclesiasticus), and Baruch), as well as some passages in Esther and Daniel, that are not included in the Jewish Scriptures. Various Orthodox Churches include a few others, typically 3 Maccabees, Psalm 151, 1 Esdras, Odes, Psalms of Solomon, and occasionally even 4 Maccabees. Protestants in general do not recognize these books are truly part of the Bible, though they may print them along with the books they do recognize.

The New Testament is a collection of 27 books, written in Koine Greek in the early Christian period, that almost all Christians recognize as Scripture: the four Gospels, the Acts of the Apostles, Letters of Saint Paul and others, and the Book of Revelation.

Influence

The Bible is arguably the most influential collection of books in human history. More copies of the Bible have been distributed than of any other book. It has also been translated more times, and into more languages, than any other book. The complete Bible, or portions, have been translated into more than 2,100 languages. It is available, in whole or in part, in the language of 90% of the world's population. Approximately 60 million copies of the entire Bible, or significant portions thereof, are distributed annually.

The Bible has had a tremendous influence not just on religion, but on language, law and culture as well, particularly in Europe and North America.

The canon of Scripture

For Jews, it is commonly thought that the canonical status of some books was discussed between 200 BCE and around 100 CE, though it is unclear at what point during this period the Jewish canon was decided.

To the books accepted by Jews as Scripture all Christians add those of the New Testament, the 27-book canon of which was finally fixed in the 4th century. As indicated above, most Christians also consider certain deuterocanonical books to be part of the Old Testament. Protestants, in general, accept as part of the Old Testament only the books in the Jewish canon and use the term Apocrypha for the deuterocanonical books. They have a 39-book Old Testament canon – the number varies from that of the books in the Tanakh because of a different way of dividing them – while the Roman Catholic Church recognizes 46 books as part of the Old Testament. For details, see Books of the Bible. For a history of the canon, see Biblical Canon.

Canonicity is distinct from questions of human authorship and the formation of the books of the Bible, questions discussed in the entries on higher criticism and textual criticism.

Biblical versions and translations

In scholarly writing, ancient translations are frequently referred to as 'versions', with the term 'translation' being reserved for medieval or modern translations. Information about Bible versions is given below, while Bible translations can be found on a separate page.

Tanakh

- Main article: Tanakh

The oldest books of the Bible are the Pentateuch, also known as the Torah. They are written in Hebrew and are also called the "Books of Moses", being traditionally attributed to the lawgiver Moses himself. Today, many believe, in line with what is called the documentary hypothesis, that the present form of the Torah is due to a redactor bringing together several earlier, distinct sources.

In addition to the Torah, the Jewish scriptures include the Nevi'im ("prophets") and the Ketuvim ("writings"), the combined tripartite collection being designated by the Hebrew acronym "Tanakh".

The original texts of the Tanakh were in Hebrew, with some portions (notably in Daniel and Ezra) in Aramaic. From the 800s to the 1400s, rabbinic Jewish scholars known as the Masoretes compared the text of all known Biblical manuscripts in an effort to create a unified standardized text; a series of highly similar texts eventually emerged, and any of these texts are known as Masoretic Texts (MT). The Masoretes also added vowel points (called niqqud) to the text, since the original text only contained consonants. This sometimes required the selection of an interpretation, since words can differ only in their vowels, and thus the meaning can vary in accordance with the choice of vowels to insert. In antiquity other variant readings existed, some of which have survived in the Samaritan Pentateuch, the Dead Sea scrolls, and other ancient fragments, as well as being attested in ancient versions in other languages.

By the year 1, most Jews no longer spoke Hebrew as a vernacular, but instead spoke Greek or Aramaic; so they made translations or paraphrases into these languages. The most important of the translations into Greek was the Septuagint version of the Torah and of other books linked with it, but other Greek translations were made as well. Versions of the Septuagint contain several passages and whole books additional to what was included in the Masoretic texts of the Tanakh. In some cases these additions were originally composed in Greek, while in other cases they are translations of Hebrew books or variants not present in the Masoretic text. Recent discoveries have shown that more of the Septuagint additions have a Hebrew origin than was once thought. While there are no complete surviving manuscripts of the Hebrew texts on which the Septuagint was based, many scholars believe that they represent a different textual tradition from the one that eventually became the basis for the Masoretic texts.

The Jews also produced non-literal translations or paraphrases known as targums, primarily in Aramaic. They frequently expanded on the text with additional details taken from Rabbinic oral tradition.

Early Christians produced translations of the Hebrew Bible into several languages; their primary Biblical text was the Septuagint. Translations were made into Syriac, Coptic and Latin, among other languages. The Latin translations were historically the most important for the Church in the West, while the Greek-speaking East continued to use the Septuagint translation of the Old Testament and had no need to translate the New Testament.

The earliest Latin translation was the Old Latin text, or Vetus Latina, which, from internal evidence, seems to have been made by several authors over a period of time. It was based on the Septuagint, and thus included the Septuagint additions.

The ever-increasing number of variants in Latin manuscripts induced Pope Damasus, in 382, to commission his secretary, Saint Jerome, to produce a reliable and consistent text. Jerome later took it on himself to make a completely new translation directly from the Hebrew of the Tanakh. This translation became the basis of the Vulgate Latin translation. Though he also translated Psalms from Hebrew, the earlier Septuagint-based version, slightly revised by him, is the text that was actually used in Church and is included in editions of the Vulgate. This includes the deuterocanonical books, also revised by Jerome, and became the official translation of the Roman Catholic Church.

New Testament

Most scholars believe that all of the New Testament was originally composed in Greek. The three main textual traditions are sometimes called the Western text-type, the Alexandrian text-type, and Byzantine text-type. Together they comprise the majority of New Testament manuscripts. There are also several ancient versions in other languages, most important of which are the Syriac (including the Peshitta and the Diatessaron gospel harmony) and the Latin (both the Vetus Latina and the Vulgate).

A few scholars believe that parts of the Greek New Testament are actually a translation of an Aramaic original. Of these, some accept the so called "Syriac" Peshitta as the original, while others take a more critical approach to reconstructing the original text. See Aramaic primacy.

The earliest critical edition of the New Testament is the Textus Receptus (Latin for "received text") compiled by the humanist Desiderius Erasmus, who had only recent Greek manuscripts at his disposal. It is largely Byzantine in character. The Textus Receptus was for many centuries the standard critical edition of the New Testament, only losing that position after the discovery of manuscripts such as the Codex Sinaiticus and the Codex Vaticanus. Some believe that many or all of the changes introduced in later critical editions are incorrect, and that the Textus Receptus is still the best available. A similar but distinct argument is sometimes made for the Majority Text.

For a more detailed account of the New Testament's development, see the relevant section of Biblical canon.

Chapters and verses

- Main article: Chapters and verses of the Bible

The Hebrew Masoretic text contains verse endings as an important feature. According to the Talmudic tradition, the verse endings are of ancient origin. The Masoretic textual tradition also contains section endings called parashiyot, which are indicated by a space within a line (a "closed" section") or a new line beginning (an "open" section). The division of the text reflected in the parashiyot is usually thematic. The parashiyot are not numbered.

In early manuscripts (most importantly in Tiberian Masoretic manuscripts, such as the Aleppo codex) an "open" section may also be represented by a blank line, and a "closed" section by a new line that is slightly indented (the preceding line may also not be full). These latter conventions are no longer used in Torah scrolls and printed Hebrew Bibles. In this system, the one rule differentiating "open" and "closed" sections is that "open" sections must always begin at the beginning of a new line, while "closed" sections never start at the beginning of a new line.

Another related feature of the Masoretic text is the division of the sedarim. This division is not thematic, but is almost entirely based upon the quantity of text.

The Byzantines also introduced a chapter division of sorts, called Kephalaia. It is not identical to the present chapters.

The current division of the Bible into chapters and the verse numbers within the chapters have no basis in any ancient textual tradition. Rather, they are medieval Christian inventions. They were later adopted by many Jews as well, as technical references within the Hebrew text. Such technical references became crucial to medieval rabbis in the historical context of forced debates with Christian clergy (who used the chapter and verse numbers), especially in late medieval Spain. Chapter divisions were first used by Jews in a 1330 manuscript, and for a printed edition in 1516. However, for the past generation most Jewish editions of the complete Hebrew Bible have made a systematic effort to relegate chapter and verse numbers to the margins of the text.

The division of the Bible into chapters and verses has often elicited severe criticism from traditionalists and modern scholars alike. Critics charge that the text is often divided into chapters in an incoherent way, or at inappropriate points within the narrative, and that it encourages citing passages out of context, in effect turning the Bible into a kind of textual quarry for clerical citations. Nevertheless, even the critics admit that the chapter divisions and verse numbers have become indispensable as technical references for Bible study.

Stephen Langton is reputed to have been the first to put the chapter divisions into a Vulgate edition of the Bible, in 1205. They were then inserted into Greek manuscripts of the New Testament in the 1400s. Robert Estienne (Robert Stephanus) was the first to number the verses within each chapter, his verse numbers entering printed editions in 1565 (New Testament) and 1571 (Hebrew Bible).

Biblical interpretation

A wealth of additional stories and legends amplifying the accounts in the Tanakh can be found in the Jewish genre of rabbinical exegesis known as Midrash.

Throughout antiquity and the medieval periods, allegorical methods of interpretation were popular. The earliest use of these was probably Philo, who attempted to make Jewish halakah palatable to the Greek mind by interpreting it as symbolising philosophical doctrines. Allegorical interpretation was adopted by Christians, and continued in popularity until a reaction against it during the Reformation, and it has not since found much favour in Western Christianity.

The Eastern Orthodox Church generally follows a patristic method of interpretation, attempting to interpret Scripture in the same way that the early Church Fathers did. It also interprets Scripture liturgically. This means that the passages that are publicly read on certain days of the liturgical year are significant, especially on feast days, and are intended to guide people in their interpretation as they are praying together. Since it was members of the Church who wrote the New Testament and a series of Church councils that decided the biblical canon, the Orthodox believe that the Church should also be the final authority in its interpretation. This often includes allegorical interpretations.

The pesher method of interpretation, which views Biblical passages as coded representations of events current to the writing of the passage, was recently (1992) put forward by Barbara Thiering, Ph.D. It is not taken seriously by most experts.

The Bible and history

The mixed archaeological record has led to a variety of opinions regarding the accuracy or historicity of Biblical accounts. Today there are two loosely defined schools of thought with regard to the historicity of the Bible (Biblical minimalism and Biblical maximalism) with many in between, in addition to the traditional religious reading of the Bible. This subject is discussed in its own entry, The Bible and history.

The supernatural in monotheistic religions

Many modern skeptical readers of the Bible hold that its authors gradually reinterpreted historical and natural events as miraculous or supernatural. Some feel these events never took place at all; that miracles are a story-teller's "wonders" and they have symbolic meanings, understood by the past generations that heard and recorded them. The article on the supernatural in monotheistic religions thus concerns itself with the junction between monotheistic religions, such as Christianity and Judaism and the supernatural.

See also

- Alleged inconsistencies in the Bible

- Bible Society

- American Bible Society

- British and Foreign Bible Society

- The Bible and history

- Bible and reincarnation

- Bible citation (an example in Epistle to the Hebrews).

- Bible errata

- Bible translations

- Bible chronology

- Biblical archaeology

- Biblical canon

- Biblical inerrancy

- Books of the Bible

- Dating the Bible

- Ecumenical council

- Gustave Doré - 19th century Bible illustrator

- Gutenberg Bible

- History of the English Bible

- Holy Writ

- Jefferson Bible

- Jewish Biblical exegesis

- Joseph Smith Translation of the Bible

- List of Biblical names

- List of names for the Biblical nameless

- List of Biblical passages

- List of Bible stories

- List of Bible passages of other than theological interest

- List of movies based on the Bible

- Peachtree Editorial and Proofreading Service

- Similarities between the Bible and the Qur'an

- Study Bible

- Tanakh

- Ten Commandments

- The Sword Project

- William Morgan (Bible translator)

References

- Dever, William B. Who Were the Early Israelites and Where Did they Come from? Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2003. ISBN 0802809758.

- Silberman, Neil A. and colleagues. The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2001. ISBN 0684869136.

- Miller, John W. The Origins of the Bible: Rethinking Canon History Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, 1994. ISBN 0809135221.

External links

On-line versions of the Bible

For those intending serious study, be aware that the links below do not show a representative sampling of Bible translations. Because these are legal web pages, many modern translations (which are subject to copyright) are not included.

Text editions in English

| See also: | ... for King James Version, World English Bible, etc. |

Protestant tradition

- Parallel Bible - Includes the various English Reformation versions.

- King James Version (KJV)

- At Project Gutenberg, Etext No. 10900:

- Start page, HTML version: http://www.gutenberg.org/dirs/1/0/9/0/10900/10900-h/10900-h.htm

- Full HTML version (zipped) downloadable from this page: http://www.gutenberg.org/etext/10900

- Older version, Etext No. 10: http://www.gutenberg.net/etext/10 - "Plain Vanilla" text

- At classic-literature.com: King James Bible - HTML version

- At freefind.com: King James Bible (with search engine)

- At believerscafe.com: Updated King James Version (UKJV)

- At bible.gospel.com: New King James Version (NKJV)

- Nicely formatted pdf version "Print Edition" New Testament (KJV)

- At Project Gutenberg, Etext No. 10900:

- American Standard Version

- Darby's Translation (1890)

- New American Standard Version

- New English Translation

- New International Version

- New Living Translation

- New Revised Standard Version

- New World Translation - Jehovah's Witnesses

- Noah Webster's Bible

- Revised Standard Version

- Young's Literal Translation

- At bible.org: New English Translation (NET Bible) - the first Bible made for the Internet

- Weymouth's New Testament Bible

- The World English Bible (WEB) - see: http://www.worldenglishbible.org or http://www.ebible.org

- At Gutenberg Project: Etext No. 8294 (full text), or 8228 to 8293 (by book, Genesis to Revelation)

- Overview (complete text, Index with Glossary, Readme): http://www.gutenberg.org/etext/8294

- Search for available editions (complete and by book): http://www.gutenberg.org/catalog/world/results?title=World+English+Bible

- The World English Bible website also contains the Messianic Edition (WEB:ME), also known as The Hebrew Names Version (HNV)

- At Gutenberg Project: Etext No. 8294 (full text), or 8228 to 8293 (by book, Genesis to Revelation)

- Wycliffe New Testament

- World English Bible - World English Bible online.

Catholic tradition

- Douay-Rheims version:

- At drbo - Online version of the complete text with the Challoner footnotes, index and search engine.

- At Project Gutenberg: Search for all available editions - complete or in parts, and/or:

- Challoner Revision: Etext No. 8300 (complete), or Nos. 8301 to 8373 (separate books from Genesis to Apocalypse):

- Older Editions: Etext No. 1581 (Complete) or Nos 1609 - 1610 (Old Testament) and 1582 (New testament)

- At ScripTOURS - Online, with search engine

- The New American Bible - Catholic translation authorized by the United States Council of Catholic Bishops.

Skeptical editions

- The Skeptic's Annotated Bible - The King James version of the Bible annotated from a skeptical point of view.

Other (or not specified) traditions

- Bible4u.info - downloadable HTML Bible

- DayByDay Bible - Bible in a Year Website

- The Inspired Version - by Joseph Smith Jr

- LDS King James Bible - Bible and other scriptures used by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

- The Orthodox Bible (in English)

- The Recovery Version New Testament - 1991 translation produced by Living Stream Ministries, founded by Witness Lee. Contains extensive footnotes, cross references etc by the founder.

- Today's New International Version (TNIV) - released in the first years of the 21st century, the TNIV is an update to the International Bible Society's New International Version, which was completed in 1978

- Bible online

- Bible Quotes

Text editions in other languages

- The Bible Gateway - Free online Bible in many translations and 40 different languages.

- Bibleserver.com - The Bible in 18 different languages with personalised user accounts.

- Greek New Testament This is the original text of the New Testament, specifically the Westcott-Hort text from 1881, combined with the NA26/27 variants.

- Full text of the Old and the New Testaments in English, Arabic, Amharic, Hebrew and French

- Bible Search - multiple translations of the Bible in searchable format

- The Polyglot Bible - allows the user to view parallel versions of the Bible in numerous ancient and modern languages.

- Bibles for the World - Index of online Bibles in many languages and types.

- VulSearch: Latin Vulgate freeware with Douay-Rheims English text

- Old English Bible - Links to portions of the Bible in Old English.

- ChamorroBible.org - Chamorro and English Scriptures (the rare 1908 Chamorro Bible) in different formats, Chamorro language resources, maps, and related material.

- e-Sword - Dozens of free Bibles in over 25 languages. See also e-Sword.

- Online Bible - The Bible in many languages and types

- John Duns Scotus Bible Reading Promotion Center, a website to promote Chinese Catholic Bible reading, contains a Chinese Catholic Bible

- Polish Millennium Biblie - official Polish translation for use in Catholic church

Illustrated and facsimile editions

- Welsh language Bible of 1588 - Facsimile.

- Albrecht Dürer illustrations of the Bible (New Testament, including Apocalyps)

- (Some of) Rembrandt's illustrations of the Bible

- The Bowyer Bible - Compiled in the early 19th century; contains illustrations by various (famous) artists of several periods.

- Bible quotes with Gustave Doré illustrations (at Project Gutenberg)

- The Flaming Fire Illustrated Bible - a project to illustrate each verse of the Bible using contributions from the public

Audio versions

- BiblePlayer for iPod - Read and hear the Bible on the iPod

- The Bible in MP3 Audio - Free audio Bible downloads in 17 languages

On-line resources for understanding and (re)interpreting the Bible

- biblekeeper.com - a free online Bible study resource for anyone who is interested in reading and researching scripture on the Internet

- believerscafe.com - Bible downloads and Bible study aids

- Bible Names - "An Interpreting Dictionary of Scripture Proper Names" from Hitchcock's New and Complete Analysis of the Holy Bible

- The Bible Decoded - A transposing of the books of John and Revelations into the philosophy of Neo-Tech

- The Bible Tool - contains a huge collection of bible texts, commentaries, glossaries, and dictionaries

- Blue Letter Bible - online interactive reference library with tools to usefully dig into original meanings of words in original Biblical languages

- GospelTruth.info - Bible information on the Gospel

- Biblical Errancy - a discussion of the internal consistency of the Bible

- bibles @ thanks4supporting.us - over 400 Megabytes of Bibles and resources

- Proving Inspiration - How to Prove Inspiration

- BibleAccess - Numerous Bible study resources.

- Bible Study Now - Free interactive online Bible Study resources.

- Bible Gateway - Tool for reading scripture online in different languages and translations.