| Revision as of 22:47, 4 June 2005 view sourceRJC (talk | contribs)Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers6,434 edits →External links: added two← Previous edit | Revision as of 03:12, 5 June 2005 view source 24.162.194.132 (talk) →An Essay Concerning Human UnderstandingNext edit → | ||

| Line 31: | Line 31: | ||

| In the ''Essay'', Locke critiques the philosophy of innate ideas and builds a theory of the mind and knowledge that gives priority to the senses and experience. His adherence to this doctrine is what marks him out as an empiricist rather than a rationalist such as his critic ], who wrote the '']''. Book II of the ''Essay'' sets out Locke's theory of ideas, including his distinction between passively acquired ''simple ideas'', such as "red," "sweet," "round," etc., and actively built ''complex ideas'', such as numbers, causes and effects, abstract ideas, ideas of substances, identity, and diversity. Locke also distinguishes between the truly existing ''primary qualities'' of bodies, like shape, motion and the arrangement of minute particles, and the ''secondary qualities'' that are "powers to produce various sensations in us" (''Essay'', II.viii.10) such as "red" and "sweet." These ''secondary qualities'', Locke claims, are dependent on the ''primary qualities''. In Chapter xxvii of book II Locke discusses personal identity, and the idea of a person. What he says here has shaped our thought and provoked debate ever since. Book III is concerned with language, and Book IV with knowledge, including intuition, mathematics, moral philosophy, ] ("science"), faith and opinion. | In the ''Essay'', Locke critiques the philosophy of innate ideas and builds a theory of the mind and knowledge that gives priority to the senses and experience. His adherence to this doctrine is what marks him out as an empiricist rather than a rationalist such as his critic ], who wrote the '']''. Book II of the ''Essay'' sets out Locke's theory of ideas, including his distinction between passively acquired ''simple ideas'', such as "red," "sweet," "round," etc., and actively built ''complex ideas'', such as numbers, causes and effects, abstract ideas, ideas of substances, identity, and diversity. Locke also distinguishes between the truly existing ''primary qualities'' of bodies, like shape, motion and the arrangement of minute particles, and the ''secondary qualities'' that are "powers to produce various sensations in us" (''Essay'', II.viii.10) such as "red" and "sweet." These ''secondary qualities'', Locke claims, are dependent on the ''primary qualities''. In Chapter xxvii of book II Locke discusses personal identity, and the idea of a person. What he says here has shaped our thought and provoked debate ever since. Book III is concerned with language, and Book IV with knowledge, including intuition, mathematics, moral philosophy, ] ("science"), faith and opinion. | ||

| == Primary, Secondary, and Tertiary qualities in Locke. == | |||

| Locke states that, “whatsoever the mind perceives in itself, or is the immediate object of perception, though or understanding,” is called an idea. He calls the power to produce an idea in our mind a quality. There are three types of qualities: primary, secondary, and tertiary. | |||

| Primary qualities are inseparable from the body no matter what force is placed upon it. The primary qualities are found in every particle which is able to be perceived. If you take the example of a grain of wheat and divide it into parts, it still has the primary qualities of “solidity, extension, figure, and mobility.” The grains of wheat retain the primary qualities no matter how many times they are divided, until the division becomes insensible. The primary qualities produce in us, “solidity, extension, figure, motion or rest, and number.” | |||

| Secondary qualities are not in the object itself but have the power to produce in us sensations through the primary qualities; the secondary qualities are also known as sensible qualities. The primary qualities, “bulk, figure, texture, and motion” produce in us the secondary qualities “colours, sounds, tastes, etc..” The tertiary qualities are barely qualities, and are defined by Locke, “For the power in fire to produce a new colour or consistence in wax or clay by its primary qualities, is as much a quality in fire as the power it has to produce in me a new idea or sensation of warmth or burning, which I felt not before, by the same primary qualities, viz., the bulk, texture, and motion of its insensible parts.” The tertiary qualities are also known as powers and depend on the primary qualities. | |||

| The primary qualities of “extension, figure, number, and motion of bodies,” come through the perceivers eyes and produces ideas in us. The secondary qualities are not in the objects themselves, but have powers to produce sensations in us, and depend on the primary qualities. The primary qualities that we perceive are actual resemblances to the primary qualities in the object, but the secondary qualities that we perceive are thought to be resemblances but are not resemblances in the object. The tertiary qualities are not thought to be resemblances in the object and are not resemblances in the object. The primary qualities alone exist and are real. The secondary qualities do not exist because they need the perceiver in order to be experienced, if we take away our senses from our body then the secondary qualities do not exist. | |||

| ===Two Treatises of Government=== | ===Two Treatises of Government=== | ||

Revision as of 03:12, 5 June 2005

For other people named John Locke, see John Locke (disambiguation).

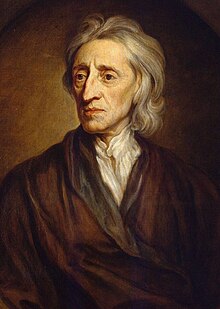

John Locke (August 29 1632–October 28 1704) was a 17th-century philosopher concerned primarily with society and epistemology. An Englishman, Locke's notions of a "government with the consent of the governed" and man's natural rights—life, liberty, and estate (property)—had an enormous influence on the development of political philosophy. His ideas formed the basis for the concepts used in American law and government, allowing the colonists to justify revolution. Locke's epistemology and philosophy of mind also had a great deal of significant influence well into the Enlightenment period. Locke has been placed in a group called the British Empiricists, which includes David Hume and George Berkeley. Locke is perhaps most often contrasted with Thomas Hobbes.

Biography

Locke was born in Wrington, Somerset, about ten miles from Bristol, England, in 1632. His father, a lawyer, served as a captain of cavalry for Parliament during the English Civil War. In 1647, Locke was sent to the prestigious Westminster School in London. After completing his studies there, he obtained admission to the college of Christ Church, Oxford. The dean of the college at the time was John Owen, vice-chancellor of the university and also a Puritan. Although he was a capable student, Locke chafed under the undergraduate curriculum of the time. He found reading modern philosophers, such as Rene Descartes, more interesting than the classical material taught at the University.

Locke earned a bachelor's degree in 1656 and a master's degree in 1658. Although Locke never became a medical doctor, he earned a bachelor of medicine in 1674. He studied medicine extensively during his time at Oxford, working with such noted virtuosi as Robert Boyle, Thomas Willis, Robert Hooke and Richard Lower. In 1666, he met Anthony Ashley Cooper, 1st Earl of Shaftesbury, who had come to Oxford seeking treatment for a liver infection. Cooper was impressed with Locke and pressed him to become part of his retinue.

Locke had been looking for a career and in 1667 moved into Shaftesbury's home at Exeter House in London, ostensibly as the household physican. In London Locke resumed his medical studies, under the tutelage of Thomas Sydenham. Sydenham had a major impact on Locke's natural philosophical thinking - an impact that resonated deeply in Locke's writing of the Essay Concerning Human Understanding.

Locke's medical knowledge was soon put to the test, since Shaftesbury's liver infection became life-threatening. Locke coordinated the advice of several physicians and was likely instrumental in persuading Shaftesbury to undergo an operation (then life-threatening itself) to remove the cyst. Shaftesbury survived and prospered, crediting Locke with saving his life.

It was in Shaftesbury's household, during 1671, that the meeting took place, described in the Epistle to the reader of the Essay, which was the genesis of what would later become Essay. Two extant Drafts still survive from this period.

Shaftesbury, as a founder of the Whig movement, exerted great influence on Locke's political ideas. Locke became involved in politics when Shaftesbury became Lord Chancellor in 1672. Following Shaftesbury's fall from favor in 1675, Locke spent some time traveling in southern France. He returned to England in 1679 when Shaftesbury's political fortunes took a brief positive turn. However, Locke fled to the Netherlands in 1683, under strong suspicion of involvement in the Rye House Plot. Locke did not return to England until after the Glorious Revolution. The bulk of Locke's publishing took place after his return. He died in 1704 after a prolonged decline in health, and is buried in the churchyard of the village of High Laver, east of Harlow in Essex, where he had lived in the household of Sir Francis Masham since 1691.

Events that happened during Locke's lifetime include the English Restoration and the Great Plague and the Great Fire of London. He did not quite see the Act of Union of 1707, though the office of King of England and King of Scotland had been held by the same person for some time. Constitutional monarchy and parliamentary democracy were in their infancy during Locke's time.

Writings

The influences of Locke's Puritan upbringing and his Whig political affiliation expressed themselves in his published writings. Although widely regarded as an important influence on modern ideas of political liberty, Locke did not always express ideas that match those of the present day.

Locke's first major published work was A Letter Concerning Toleration. Religious toleration within Great Britain was a subject of great interest for Locke; he wrote several subsequent essays in its defense prior to his death. Locke's upbringing among non-conformist Protestants made him sensitive to differing theological viewpoints. He recoiled, however, from what he saw as the divisive character of some non-conformist sects. Locke became a strong supporter of the Church of England. By adopting a latitudinarian theological stance, Locke believed, the national church could serve as an instrument for social harmony.

Locke is best known for two works, An Essay Concerning Human Understanding and Two Treatises of Government. The Essay was commenced in 1671, and as Locke himself described, was written in fits and starts over the next 18 years. It was finally published in December 1689. Though the exact dates of the composition of the Two Treatises are a matter of dispute, it is clear that the bulk of the writing took place in the period from 1679-1682. It was therefore much more of a commentary on the exclusion crisis than it was a justification of the Glorious Revolution of 1688, though no one doubts thats Locke substantively revised it to serve this latter purpose.

An Essay Concerning Human Understanding

In the Essay, Locke critiques the philosophy of innate ideas and builds a theory of the mind and knowledge that gives priority to the senses and experience. His adherence to this doctrine is what marks him out as an empiricist rather than a rationalist such as his critic Leibniz, who wrote the New Essays on Human Understanding. Book II of the Essay sets out Locke's theory of ideas, including his distinction between passively acquired simple ideas, such as "red," "sweet," "round," etc., and actively built complex ideas, such as numbers, causes and effects, abstract ideas, ideas of substances, identity, and diversity. Locke also distinguishes between the truly existing primary qualities of bodies, like shape, motion and the arrangement of minute particles, and the secondary qualities that are "powers to produce various sensations in us" (Essay, II.viii.10) such as "red" and "sweet." These secondary qualities, Locke claims, are dependent on the primary qualities. In Chapter xxvii of book II Locke discusses personal identity, and the idea of a person. What he says here has shaped our thought and provoked debate ever since. Book III is concerned with language, and Book IV with knowledge, including intuition, mathematics, moral philosophy, natural philosophy ("science"), faith and opinion.

Primary, Secondary, and Tertiary qualities in Locke.

Locke states that, “whatsoever the mind perceives in itself, or is the immediate object of perception, though or understanding,” is called an idea. He calls the power to produce an idea in our mind a quality. There are three types of qualities: primary, secondary, and tertiary.

Primary qualities are inseparable from the body no matter what force is placed upon it. The primary qualities are found in every particle which is able to be perceived. If you take the example of a grain of wheat and divide it into parts, it still has the primary qualities of “solidity, extension, figure, and mobility.” The grains of wheat retain the primary qualities no matter how many times they are divided, until the division becomes insensible. The primary qualities produce in us, “solidity, extension, figure, motion or rest, and number.”

Secondary qualities are not in the object itself but have the power to produce in us sensations through the primary qualities; the secondary qualities are also known as sensible qualities. The primary qualities, “bulk, figure, texture, and motion” produce in us the secondary qualities “colours, sounds, tastes, etc..” The tertiary qualities are barely qualities, and are defined by Locke, “For the power in fire to produce a new colour or consistence in wax or clay by its primary qualities, is as much a quality in fire as the power it has to produce in me a new idea or sensation of warmth or burning, which I felt not before, by the same primary qualities, viz., the bulk, texture, and motion of its insensible parts.” The tertiary qualities are also known as powers and depend on the primary qualities.

The primary qualities of “extension, figure, number, and motion of bodies,” come through the perceivers eyes and produces ideas in us. The secondary qualities are not in the objects themselves, but have powers to produce sensations in us, and depend on the primary qualities. The primary qualities that we perceive are actual resemblances to the primary qualities in the object, but the secondary qualities that we perceive are thought to be resemblances but are not resemblances in the object. The tertiary qualities are not thought to be resemblances in the object and are not resemblances in the object. The primary qualities alone exist and are real. The secondary qualities do not exist because they need the perceiver in order to be experienced, if we take away our senses from our body then the secondary qualities do not exist.

Two Treatises of Government

The First Treatise attacks Sir Robert Filmer, who was the author of the first criticism of Thomas Hobbes and of a peculiar theory of the Divine Right of Kings. The Second Treatise, or On Civil Government, purports on its face to justify the Glorious Revolution by 1) developing a theory of legitimate government and 2) arguing that the people may remove a regime that violates that theory; Locke leaves it to his readers to understand that James II of England had done so. He is therefore best known as the popularizer of natural rights and the right of revolution.

Locke posits a state of nature as the proper starting point for examining politics. Individuals have rights, and their duties are defined in terms of protecting their own rights and respecting those of others; this is the content of the law of nature. In practice, the law of nature is ignored and so government is necessary; this can be created only by consent, and only to a commonwealth of laws. As law is sometimes incapable of providing for the safety and increase of society, man may acquiesce in being done certain extralegal benefits (prerogative). All government is therefore a fiduciary trust: when that trust is betrayed, government dissolves. A government betrays its trust when the laws are violated or when the trust of prerogative is abused.

Locke and the United States

Supporters

Locke's work, particularly the concepts of liberty, later influenced the written works of Thomas Jefferson and other Founding Fathers of the United States. In particular, the United States Declaration of Independence drew upon many 18th century political ideas, derived from the works of both Locke and Montesquieu.

Detractors

According to A People's History of the United States:

- In the Carolinas, the Fundamental Constitutions were written in the 1660s by John Locke, who is often considered the philosophical father of the Founding Fathers and the American system. Locke's constitution set up a feudal-type aristocracy, in which eight barons would own 40 percent of the colony's land, and only a baron could be governor. When the crown took direct control of North Carolina, after a rebellion against the land arrangements, rich speculators seized half a million acres (2,000 km²) for themselves, monopolizing the good farming land near the coast. Poor people, desperate for land, squatted on bits of farmland and fought all through the pre-Revolutionary period against the landlords' attempts to collect rent. (47)

- Locke's statement of people's government was in support of a revolution in England for the free development of mercantile capitalism at home and abroad. Locke himself regretted that the labor of poor children "is generally lost to the public till they are twelve or fourteen years old" and suggested that all children over three, of families on relief, should attend 'working schools" so they would be "from infancy inured to work." (73f)

Locke also provided intellectual justifications for taking the land of the Native Americans. Bhikhu Parekh writes Locke "argued that since the American Indians roamed freely over the land and did not enclose it ... could be taken over without their consent". When it was discovered that some land was enclosed, Locke argued that enclosure was not sufficient since the Native Americans paused every three years to enrich the soil. This "irrational" behavior meant that the Native Americans were uncivilized and thus did not deserve the land. "In Locke's view," Parekh comments, "the trouble with the Indians was that they had very few desires and were easily contented." Nor did Native American society count as a legitimate government, since it lacked "a single, unified and centralized system of authority" nor did they have a single language or culture. (Quotes from Parekh, "Liberalism and Colonialism" in The decolonization of imagination.)

List of major works

- (1689) A Letter Concerning Toleration

- (1690) A Second Letter Concerning Toleration

- (1692) A Third Letter for Toleration

- (1689) Two Treatises of Government

- (1689) An Essay Concerning Human Understanding

- (1693) Some Thoughts Concerning Education

- (1695) The Reasonableness of Christianity, as Delivered in the Scriptures

- (1695) A Vindication of the Reasonableness of Christianity

- (1697) A Second Vindication of the Reasonableness of Christianity

Major unpublished or posthumous manuscripts

- (1660) First Tract on Government (or the English Tract)

- (c.1662) Second Tract on Government (or the Latin Tract)

- (1664) Essays on the Law of Nature

- (1667) Essay Concerning Toleration

- (1706) Of the Conduct of the Understanding

- (1707) A Paraphrase and Notes on the Epistles of St. Paul

Locke's epitaph

(translated from the Latin) "Stop Traveler! Near this place lieth John Locke. If you ask what kind of a man he was, he answers that he lived content with his own small fortune. Bred a scholar, he made his learning subservient only to the cause of truth. This thou will learn from his writings, which will show thee everything else concerning him, with greater truth, than the suspected praises of an epitaph. His virtues, indeed, if he had any, were too little for him to propose as matter of praise to himself, or as an example to thee. Let his vices be buried together. As to an example of manners, if you seek that, you have it in the Gospels; of vices, to wish you have one nowhere; if mortality, certainly, (and may it profit thee,) thou hast one here and everywhere."

Secondary literature

- Bernard Bailyn, The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknapp/Harvard University Press, 1967. Enlarged Edition, 1992. Discusses influence of Locke and other thinkers upon American political thought.

- John Dunn, Locke Oxford University Press, 1984. A succinct introduction.

- John Dunn, The Political Thought of John Locke: An Historical Account of the Argument of the Two Treatises of Government. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1969. Introduced the interpretation which emphasizes the theological element in Locke's political thought.

- Roland Hall (ed.) `Locke Studies' is an annual journal of research on John Locke (obtainable from the editor for £12; the current volume is 300 pages).

- John W. Yolton (ed.), John Locke: Problems and Perspectives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1969. Reassesses Locke's political philosophy from different points of view.

See also

External links

- Free, full-text works by John Locke

- John Locke at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Locke on the Web

- John Locke Online Bibliography

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry

- John Locke Bibliography

- John Locke Manuscripts