| Revision as of 11:31, 3 September 2007 editEvlekis (talk | contribs)30,289 editsNo edit summary← Previous edit | Revision as of 11:32, 3 September 2007 edit undoEvlekis (talk | contribs)30,289 editsNo edit summaryNext edit → | ||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

| :''For the religious terminology see ].'' | :''For the religious terminology see ].'' | ||

| '''Macedonism''' (] and ]: Македонизам, ]: |

'''Macedonism''' (] and ]: Македонизам, ]: Македонизъм, all ]: ''Makedonizam'') is a term used in ],<ref name=Genov>Nikolaĭ Genov, Anna Krŭsteva, (2001) ''Recent Social Trends in Bulgaria, 1960-1995'', </ref> the ],<ref></ref> and referred to in ],<ref>See ]</ref> and in the Western scholarship<ref name=Bousfield>Jonathan Bousfield, Dan Richardson, Richard Watkins, (2002) ''The Rough Guide to Bulgaria 4'', Rough Guides, ISBN 1858288827, </ref><ref name=Gillespie>Richard Gillespie (1994) ''Mediterranean Politics'', , </ref><ref name=Danforth>] (1995), ''The Macedonian Conflict: ethnic nationalism in a transnational world'', </ref><ref name=Bell>John D. Bell, edited by Sabrina P Ramet - (1999) ''The Radical Right in Central and Eastern Europe Since 1989'', </ref> | ||

| to describe an ] and ] ideology promoted by certain circles in the ] and the (Slav/ethnic) Macedonian diaspora, regarding the ]. | to describe an ] and ] ideology promoted by certain circles in the ] and the (Slav/ethnic) Macedonian diaspora, regarding the ]. | ||

Revision as of 11:32, 3 September 2007

- For the religious terminology see Macedonianism.

Macedonism (Macedonian and Serbian: Македонизам, Bulgarian: Македонизъм, all transliterated: Makedonizam) is a term used in Bulgaria, the Republic of Macedonia, and referred to in Greece, and in the Western scholarship to describe an irridentist and revisionist ideology promoted by certain circles in the Republic of Macedonia and the (Slav/ethnic) Macedonian diaspora, regarding the Macedonian region.

Introduction

In an extreme context, the word itself means that there is no genuine, but only contrived Macedonian nationhood, an ideological mindset imposed by Yugoslav socialism (Titoism). In Bulgaria, to some extent in Greece and the Republic of Macedonia, this term is used to describe either a political ideology or a form of ethnic nationalism and a regional linguistic separatist movement, according to which the Slavic-speaking population in Macedonia forms a separate ethnic group, possessing unique language and separate history, independent first and foremost of the Bulgarian, and to a lesser extent from the Serbian and Greek language and history respectively. In Greece this term is used almost exclusively by Kofos in the context of United Macedonia related subjects.

The term is chiefly a Balkan regionalism, rarely used in the English historiography. It is found neither in Encyclopedia Britanica nor in the Oxford English Dictionary.

In the article The Macedonian Question by Petko Rachev Slaveykov, published on 18th January 1871 in the "Macedonia" newspaper in Constaninople, Macedonism was criticized, his adherents were named Macedonists, and this is the earliest surviving indirect reference to it, although Slaveykov never used the word Macedonism. The term's first recorded use is from 1887 by Stojan Novakovic to describe Macedonism as a potential ally for the Serbian strategy to expand its territory toward Macedonia, whose population was regarded by almost all neutral sources as Bulgarian at the time (See Demographic history of Macedonia).

Issues

This term is widely used in Bulgaria due to the Bulgarian reaction against presumed attempts at falsification of history by the Republic of Macedonia. It is often used by nationalists, like Dr. Bozhidar Dimitrov, the author of The Ten Lies of Macedonism. The term is also used in the Republic of Macedonia, mainly to address issues raised by the critics of Macedonism, though in some cases it used to describe the emergence of Serbian propaganda in Macedonia in the late 19th century.

The term can also be used by Bulgarians or their supporters as an epithet referring to Macedonians from the Republic of Macedonia who seek to downplay their connections with Bulgarians, or in some way exert claims of separate Macedonian heritage over certain groups of people outside the Republic of Macedonia - e.g. "macedonistic organization", "macedonistic orientation".

Generally, the term itself is considered biased by many ethnic Macedonians, as well as being offensive and directly attacking the Republic of Macedonia. It is claimed that it is prevalently used in Bulgaria, as a direct expression of the claim that the Macedonians are in fact part of the Bulgarian ethnic group, as well as that it represents a doctrinaire idea. Ethnic Macedonians rather use the term Macedonian National Movement.

According to the critics of Macedonism, its usage of historical sources and documents is generally selective and inconsistent, as anything adverse to the Macedonistic perspective is deemed to be foreign (usually Bulgarian, Greek or Serbian) propaganda, with the intent to deny the Macedonian nation (see also petitio principii).

For example, throughout high schools in the Republic of Macedonia, the organization of revolutionaries from the late 19th century is presented under the name Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Committees, and the existence of the Bulgarian Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Committees is not mentioned. Until the early 1990s the name of the collection entitled Bulgarian Folk Songs by Miladinov Brothers was presented as Macedonian Folk Songs. In addition, the Bulgar ancestry of Bulgarians is overemphasized, and the Bulgar ancestry of ethnic Macedonians is kept silent. Similarly, the alleged Ancient Macedonian ancestry of ethnic Macedonians is overemphasized at the expense of their Paeonian and Dardanian ancestry, and to some extent of their predominantly Slavic ancestry.

Nonetheless, the following statements about Macedonism are made:

Ethnicity

It has been claimed by the supporters of Macedonism that the Slav-speaking inhabitants of the contemporary region of Macedonia constitute a separate ethnic group (regardless of their self-determination). In other words, ethnicity is prescribed on a regional basis, rather than being self-expressed. Additionally, the Macedonian ethnic group is the only indigenous ethnic group to Macedonia, with the Greeks (historically known as Macedonians in this region), at present forming the majority of the population of Macedonia, being immigrants (or the descendants of immigrants) settled in Aegean Macedonia by the Greek government in the 1920s in order to alter the ethnic composition, which Macedonism supporters claim to have been ethnic Macedonian before the event.

The critics of this claim usually ignore the concept of self determination . Ethnic Macedonian organizations in Greece and Bulgaria have reported official harassment. The Bulgarian Constitutional Court banned a small Macedonian political party in 2000, convicting it as separatist and financed by the government of the Republic of Macedonia.

Ethnic Macedonians (assuming such a group existed) had little or no political national identity of their own until the 20th century. Any Macedonian identity during the Byzantine centuries is mostly expressed through the Greek medium. Medieval sources traditionally describe them as Bulgarians, a definition which survived well into the period of Ottoman rule as attested by the Ottoman archives and by descriptions of historians and travelers, for example Evliya Celebi and his Seyahatname - Book of Travels. There is ample evidence that certain Macedonian Slavs considered themselves Serbs and that the northern regions of Geographic Macedonia were sometimes considered Serbian during the Ottoman period.

During the Ottoman rule, there is no documentation attesting to a specific Macedonian national identity, be it Slav, Greek or otherwise, until the 20th century. From the 17th century, authors who declared themselves 'Macedonian' did so in the context of publishing Greek books and belonging to the Greek nation. 19th century ethnographers and travelers were generally united in identifying the Slavic speakers as Bulgarians. A significant number of the ancestors of the present-day ethnic Macedonians did, in fact, identify themselves as Bulgarians until the early 20th century.

Historical basis of ethnicity

Claims

It has been claimed by the supporters of Macedonism that the inhabitants of the Republic of Macedonia are largely the descendants of the Ancient Macedonians, because of which claims are made over various insignia from the kingdom of Macedon, notably the Vergina Sun, which is presented as "symbol of all ethnic Macedonians".It has been also claimed that the Ancient Macedonians spoke a Slavic language.

There existed a distinct Macedonian ethnic group in the Middle Ages, culminating with the rule of Tsar Samuil and his Macedonian/Slavic kingdom, despite Samuil being internationally recognized as "King of all Bulgarians" and various stone tablets and historic references from the time period confirming the Bulgarian ethnic character of his kingdom. The general consensus is that Tsar Samuil was indeed ruler of Bulgaria, fact stated by Byzantine historians from the period, as well as confirmed by the Bitola inscription.

The name Bulgarian meant Christian or Slav before the beginning of the 20th century, instead of referring to the Bulgarian people. For that reason, people born in the region such as Gotse Delchev, Kuzman Shapkarev and Grigor Parlichev were declaring that they are Bulgarian. Also Macedonists use this claim to explain the fact that no Macedonians were recorded in any census conducted prior to the 1920s, rather a mixture of Albanians, Aromanians, Bulgarians, Greeks, Serbs and Turks. See Demographic history of Macedonia#Statistical data.

Comments

Antiquity

According to Macedonian Slav authors, there is rich oral tradition mentioning Alexander the Great, Philip II, even Karanus of Macedon founder of Macedon 8th century BC. This is despite the fact that the modern Macedonian nation lives mostly in present-day Vardar Macedonia, which in ancient times was inhabited mainly from Paionians and other Thraco-Illyrian tribes as Dardani. Paionia or Paeonia was in ancient geography, the land of the Paeonians, the exact boundaries of which, like the early history of its inhabitants, are very obscure. In the time of king Philip II of Macedon, Paionia covered most of what is now the Republic of Macedonia, and was located immediately north of ancient Macedon.

The government of the Republic of Macedonia, through its Academy of Sciences and Arts, is promoting a theory put forward by two professors in Skopje that the "Demotic" script on the Rosetta stone is in fact a text in a Slavic language.. The new pseudoscientifical theory about Rosetta stone contradicts all previous interpretations of the Stone, and the mainstream scientific belief that Slavic speakers did not reach Macedonia until the 6th Century CE. This promotion is part of a wider effort by scientists in the former Yugoslav Republic to link the Ancient Macedonians with a Slavic-speaking people, despite all evidence to the contrary

Middle Ages

School Textbooks in FYRO Macedonia do not mention about the mass settlement of Bulgars led by Kouber in the region, but with regard to the origins of the Bulgarian people, Macedonists attempt to emphasize the distinction between the Macedonian and Bulgarian ethnic group by claiming the present Bulgarian people are predominantly the descendants of the Bulgars rather than Slavs. At the same time in any Macedonist's work nothing has been mentioned about the settlement of Bulgars led by Kouber in the region of Macedonia.

There are no tales about Bulgarian tsars on the other hand, including Tsar Samuil, but thera are tales about Alexander the Great, whatever that might imply about the origins of the Macedonian people. On the other hand, the Bulgarian side specifies that the folklore sources about Alexander the Great is widespread in the wide region - right up to Far East and there is at least one folksong from Macedonia about the last ruler of the Second Bulgarian Empire Ivan Shishman.

Various other statements are made in the literature, including the claim that present day Bulgarians are Tatars, generally ignoring the fact that Bulgaria had become a predominantly Slav country by the late 9th century.A typical Macedonistic slogan is: "Bulgarians are Tatars". Macedonian school textbooks contain no information about the later Middle Age's settlements in the region from Kumans, Pechenegs, Uzes and other Turkic peoples.

Bulgaria under Tsar Samuil

According to Macedonian and other historians from the former Yugoslavia, the Samuil Empire had some unique differences from its predecessors. For more details, see Samuil of Bulgaria#Other theories. There are number of documents mentioning Macedonians, which according to the Macedonists refer to the Macedonian ethnic group, rather than collectively to people in the region of Macedonia. Macedonian people were first mentioned in 1027 („natio macedonum“) in the three most important documents of Bari (Annales Barenses, Lupi Protospatharii и Anonymi barensis chronicon.). Macedonians as an ethnic group were first mentioned in early 13th century (J. Pitra, Analecta sacra et classica specilegio Solesmensi parta, t. VI Juris ecclesiastici graecorum selecta paralipomena). Cardinal J. Rita in (Collection of Canon laws Parissis et Romae 1891, col. 315) there are 50 families with Macedonian ethnicity during Ohrid Archbishop Demetrius Homatian (1216-1235). Similar ideas of this time can be found in the works of the Bulgarian historian D. Angelov (Prinot KJM Narodostite i Pozemleni Otnoshenja vo Makedonija pp. 11-12 et. seq.; 43). The manifesto of Leopold I from 1690 invited Macedonian people to be under imperial protection (along with separate letters made for Bulgaria and Serbia) . Generally, prior to the beginning of the 20th century the adjective "Macedonian" was used either as a regional designator or with regard to the Ancient Macedonians.

Regarding the Bitola Inscription the critics points that the phrase “Bulgarian by birth” in the Slavic languages shows the origin (geographical, ethnic, confessional, religious. Many parallel in that relation could be found in Byzantium, for Romans, Macedonians, Thracians etc. by birth). Regarding Samuil origin, despite Bitola Inscription , there are four theories: Armenian, Bulgar, Brsjak, or Christianized Jew. The Bulgarian historians look at the mentioning about some Macedonians in the Middle Ages as an exception - on the background of the frequent indications about Bulgarians in Macedonia in these times. Often the term Macedonians is interpreted as a regional term or as an adjective remained from Antiquity without any ethnical sense like many other ancient names: Moesians, Scythians, Tribals etc. - terms used about many different peoples in the Middle Ages (Bulgarians, Serbians, Cumans and others)

Bulgarian Archbishopric of Ohrid

The Bulgarian Archbishopric of Ohrid is according to the supporters of Macedonism a church established to support ethnic Macedonians during the Middle Ages, independent of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church. The claim is closely related to that of the non-Bulgarian character of kingdom of Samuil.

The Ottoman Empire

The millets of the Ottoman Empire were not homogenous, and there were often divisions within them. Sources from that period use terms such as "party," "side," and "wing" when referring to various Christian camps. Scholars from that period distinguished between Greeks, Vlachs, Albanians, Bulgarians and Serbs, although frequently, all Slavs of Macedonia were recorded as Bulgarians. Serbian policy in Macedonia had a distinctively anti-Bulgarian flavour, and aimed to prevent the Bulgarian Exarchate (established in 1870) influencing the inhabitants of Macedonia; this would have the effect of justifying Serbian territorial claims over Macedonia.

While the Bulgarian scientists focused on eliminating any ethnic diversity between the Slavs of Macedonia and the Slavs in Moesia and Thrace, Serbian propaganda was aimed at preventing the Slavic-speaking Macedonians from acquiring Bulgarian identity. According to David Kertzer, at that time, Bulgarian and Serbian nationalists would present the Slavic languages of Macedonia as dialects of their own languages. This situation prompted certain intellectuals from that period such as Krste Misirkov to mention the necessity of creating a Macedonian national identity which would distinguish the Macedonian Slavs from Bulgarians, Serbians or Greeks, there is no evidence those people from the region who declared as Bulgarians (Gotse Delchev, Kuzman Shapkarev and Grigor Parlichev and others) ever had any other identity than Bulgarian. The perception of the existence of a Macedonian ethnicity at that time or earlier in the absence of any evidence emerges as a historical hindsight.

This was, according to the supporters of Macedonism, confirmed with the proclamation of Kresna Uprising which is viewed as а completely forged document from Bulgarian scientists.

On the other hand Kuzman Shapkarev writes to Marin Drinov in 1888 with regard to the usage of the words Macedonian and Bulgarian:

"But even stranger is the name Macedonians, which was imposed on us only 10 to 15 years ago by outsiders, and not as something by our own intellectuals. .. Yet the people in Macedonia know nothing of that ancient name, reintroduced today with a cunning aim on the one hand and a stupid one on the other. They know the older word: "Bugari", although mispronounced: they have even adopted it as peculiarly theirs, inapplicable to other Bulgarians. You can find more about this in the introduction to the booklets I am sending you. They call their own Macedono-Bulgarian dialect the "Bugarski language", while the rest of the Bulgarian dialects they refer to as the "Shopski language".

IMRO and Ilinden Upspring

According to Macedonian historians the Bulgarian falsification of Macedonian history is still desperately attempting to present the ethnic Macedonians as Bulgarians. The dissatisfaction of the Macedonian people in Ottoman Empire was expressed through the revolts and rebellions of the first half of the 19th century; but by mid-century, it found its release through the organization of a movement for national liberation. This movement culminated in the formation of the Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO) at the end of the century. After all, the Macedonian revolutionaries fought for independent Macedonia and the motto of the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization was "Macedonia for the Macedonians". A meeting of IMRO's General Staff held on July 13, 1903 planned a general uprising to begin on July 20, 1903. While the established during the Upspring Krushevo Republic was quickly brought to an end, "in spite of its short existence, it represents one of the most significant phenomenon in the Macedonian national-liberation movement. Created in the flames of the struggle it was at the same time an expression of the desire of the Macedonians for the creation of a national state. Hence, the proclamation of the Krushevo Republic represents the highest accomplishment and one of the most important state-legal acts of the Macedonian insurgents.

However the organization was founded in 1893 in Ottoman Thessaloniki by a group of Bulgarian exarchist revolutionaries from Macedonia led by Hristo Tatarchev, Dame Gruev, Petar Pop-Arsov, Andon Dimitrov, Hristo Batandzhiev and Ivan Hadzhinikolov.

In Dame Gruev's memoirs, the MRO's goals are stated as follows:

- We grouped together and jointly worked out a statute. It was based on the same principles: demand for the implementation of the Berlin Treaty. The statute was worked out after the model of the Bulgarian revolutionary organisation before the Liberation. Our motto was "Implementation of the resolutions of the Berlin Treaty". We established a "Central Committee" with branches, membership fees, etc. Swearing in for each member was also envisaged.

According to Dr. Hristo Tatarchev:

- We talked a long time about the goal of this organization and at last we fixed it on autonomy of Macedonia with the priority of the Bulgarian element. We couldn't accept the position for "direct joining to Bulgaria" because we saw that it would meet big difficulties by reason of confrontation of the Great powers and the aspirations of the neighbouring small countries and Turkey.

Based on circumstantial evidence it has been conjectured by Bulgarian and accepted by Western historians that in 1896 or 1897 its name was Bulgarian Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Committees and the organisation existed under this name until 1902 when it changed it to Secret Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Organization (SMARO).

The Ilinden-Preobrazhenie Uprising of August 1903 was an organized revolt against the Ottoman Empire prepared and carried out by the Secret Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Organisation. It took place in the Bitola vilayet and the northeastern part of Adrianople vilayet — parts of the regions of Macedonia and Thrace. The rebellion in the Bitola vilayet was proclaimed on 2 August (Gregorian Calendar, St. Elias' Day, the celebration of the ascension of the Prophet Elijah to Heaven, almost two weeks ahead of schedule. The Adrianople vilayet joined the uprising on 19 August 1903, the Transfiguration. The rebellion in Macedonia affected most of the central and southwestern parts of the Bitola Vilayet receiving the support of the local Bulgarian peasants, Grecomans and Vlach population of the region. Provisional governments were established in three localities, all of them Vlach towns or villages. In Krushevo the insurgents proclaimed the so called Krushevo Republic under the presidency of the school teacher Nikola Karev.

The bulgarian rebellion in the Adrianople vilayet led to the liberation of a vast area in the Strandzha Mountains and to the creation of a provisional government in Vassiliko, the so called Strandzha Republic. Although the rebellion in both regions initially was successful, the intervention of Turkish regular army led to the dissolution of the rebels' detachments.

National Liberation War of Macedonia

After the invasion of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and when most of Yugoslavia was annexed by Axis Powers, ethnic Macedonians had begun organizing their resistance. It was not until a revolt in October 11, 1941 by the Prilep Partisan Detachment that a national war for the liberation of a Macedonian state was launched. Armed insurgents from the Prilep Partisan Detachment attacked Axis occupied zones in all regions of historic Macedonia. After the attacks, a national movement for liberation had been identified in Macedonia. Partisan detachments were formed in Greek Macedonia (Aegean Macedonia) and the Blagoevgrad Province (Pirin Macedonia) and had set different goals regionally for the incorporation of those regions into a future state.

Since the formation of a Macedonian army and Communist party in 1943, ethnic Macedonians were trying to, for the first time, create an autonomous government. In Spring of 1944 the Macedonian National Liberation Army launched an operation called "The Spring Offensive" which engaged an estimated 60,000 German and Bulgarian fascist soldiers and lasted until June of that year until Bulgarian and German forces withdrew.

However the Bulgarian army entered Yugoslav Vardar Macedonia on April 19th. 1941.(see the photos:) It was greeted by most of the population as liberators. Former IMRO members were active in organising Bulgarian Action Committees charged with taking over the local authorities. Metodi Shatorov, who was a leading member of the Yugoslav Communist Party, also refused to define the Bulgarian forces as occupiers.The Macedonian Regional Committee refused to remain in contact with YCP and linked up with BCP as soon as the invasion of Yugoslavia started. Shatorov refused to distribute the proclamation of the YCP calling for military actions against Bulgarians.Thousands of Macedonian soldiers who had been conscripted into the Yugoslav army and captured by the Germans and Italians have been liberated as Bulgarians.

Before the German invasion in USSR there has not been any resistance in Vardar Banovina. The German invasion of the Soviet Union caused a wave of protests, which led to the activization of a guerilla movement headed by the depending on Comintern underground CPY and BCP.After that and when already most of Yugoslavia was annexed by Axis Powers. Macedonian partisans, many of which not ethnic Macedonians, had begun organizing their resistance. In early September of 1944 IMRO leader Ivan Mihaylov was offered by the Germans in Skopje to head a future pro-German Macedonian state but he declined favouring the occupation of Vardar Macedonia by Bulgaria. On September 9th 1944 the Fatherland Front made a coup d'état and deposed the pro-German government. Already the following day the new government declared war on Nazi - Germany and all its allies. After the declaration of war by Bulgaria on Germany, the Bulgarian troops, surrounded by German forces and betrayed by high-ranking military commanders, fought their way back to the old borders of Bulgaria. Under the leadership of a new Bulgarian pro-Communistgovernment,Under the leadership of a new Bulgarian pro-communist government three Bulgarian armies (some 500,000 strong in total) entered occupied Yugoslavia in September 1944 and moved from Sofia to Niš and Skopje with the strategic task of blocking the German forces withdrawing from Greece. Southern and eastern Serbia and Macedonia were liberated within a month.

However, the Bulgarian army during the annexation of the region was partially recruited from the local population, which formed as much as 40% of the soldiers in certain battalions. Some official comments of deputies in Macedonian parliamentand of a former Premier - Ljubčo Georgievski after 1991 announced the struggle was civil but not a liberation war. According to official sources the number of Macedonian communist partisan's victims against Bulgarian army during World War II was 539 man, which is not a high level. Bulgarian historian and director of the Bulgarian National Historical Museum Dr. Bozhidar Dimitrov, in his 2003 book The Ten Lies of Macedonism, has also questioned the extent of resistance of the local population of Vardar Macedonia against the Bulgarian forces.

Anthropological and genetical basis of ethnicity

In the Republic of Macedonia, Alexander Donski is considered an influential historian, despite the fact that as of 2006 he has not obtained an academic degree in history. One of his most celebrated works is "Ethnological differences between Macedonians and Bulgarians", in which according to some historians, pseudoscientific and racialist statements are used to support the anthropological claims that present-day Bulgarians and present-day ethnic Macedonians are completely unrelated people. For example, works of fiction are used as historical reference. Notably, Alexander the Great is presented as ethnic Macedonian. Bulgarians are described as Mongoloids and the "Macedonians" as descendants of Indo-Europeans. This is despite the fact that one of the most prominent anthropologists of 20 Century Carleton Coon in his book the Races of Europe regarded the ethnic Macedonians as Bulgarians.. Later research by Bertil Lundman in his book The Races And Peoples Of Europe has also placed both people in a common subgroup.

Another example is "Gatanka" (Puzzle) by Nikola Spasikov. Here he suggested some genetical claims as: "Genetic analysis has shown that modern Bulgarians have genetic markers similar to those of Asian origins. Modern Bulgarian DNA has been greatly influenced by DNA from Asia. No Asian DNA has been found in modern Macedonians... Genetic analysis also shows that modern Greeks belong to the newer Mediterranean stratum, and are related to the sub Saharan, Negroid people." All of these racialist statements have been proven scientifically incorrect and absolutely false. On the contrary all genetic researches put the people of these three nations in the same Balkan cluster sampling. It is also corroborated that there is some noneuropean (African and Asiatic) inflow in the modern Macedonians as apparently in most Europeans., , , , .

Minority populations

Claims

It has been claimed by Macedonists that there exist large and oppressed ethnic Macedonian minorities in the region of Macedonia, located in neighboring Albania (up to 350,000 people), Bulgaria (up to 200,000, mainly in Blagoevgrad Province), Greece (up to 1 million in Greek Macedonia) and Serbia (about 20,000 in Pčinja District). Because of those claims, irredentist proposals are being made calling for the expansion of the borders of the Republic of Macedonia to encompass the territories allegedly populated with ethnic Macedonians, either directly or through initial independence of Blagoevgrad province and Greek Macedonia, followed by their incorporation into a single state. (See United Macedonia). The population of the neighboring regions is presented as "subdued" to the propaganda of the governments of those neighboring countries, and in need of "liberation".

Comments

Because separate ethnic status of Macedonians is by some accounts not fully recognized in Bulgaria and Greece , there can be only speculation about the actual numbers, including the possibility that there is no Macedonian minority at all in those countries. In the censi of 1948 and 1956, where according to Macedonian Slav sources, Macedonians in Bulgaria were allowed to declare freely, and according to Bulgarians were forced under pressure from Moscow as a step towards planned incorporation of the entire region of Macedonia in Yugoslavia, showed overwhelming majority in Blagoevgrad Province. However, in subsequent censi, following the Tito-Stalin split, and at present where Bulgaria is in the process of acceding to the European Union, only a small number of ethnic Macedonians were recorded. In the latest census of 2001 there were 5071 ethnic Macedonians recorded.

The supporters of Macedonism generally ignore censi conducted in Albania, Bulgaria and Greece, which show minimal presence of ethnic Macedonians. They consider those censi flawed, without presenting evidence in support, and accusing the governments of neighboring countries of continued propaganda. Additionally, the presence of ethnic Greeks in Macedonia has been documented for centuries before the 1920s, with the Ottoman census of 1911 showing Greeks as being the largest Christian population in the vilayets of Thessaloniki and Bitola, even superseding Bulgarians (ethnic Macedonians were not recorded). According to Encyclopædia Britannica, Macedonia had an ethnic Greek composition before the arrival of the Slavs in the 6th century - the claim that the only Greeks in Macedonia are the immigrants of the 1920s, has no basis in fact. Additionally, in the Encyclopædia Britannica article on the region of Macedonia in Greece, in the list of ethnic groups inhabiting the region (Greeks, Roma etc), ethnic Macedonians are not included.

Censi

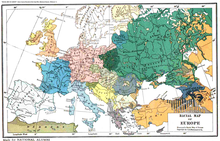

According to Macedonists, the statistical data available concerning turn of the century Macedonia serves graphically to underscore the fact that such data are extremely unreliable, in order to explain the fact that no "Macedonians" were recorded in censi conducted prior to the beginning of the 20th century, rather Albanians, Bulgarians, Greeks, Turks, Vlachs and Jews. According to them, most figures are based upon the estimates of politically motivated parties who used them as an exercise for numerical manipulation for political ends.

Serbian Invention

Many critics claim that Macedonism is a Serbian invention, not just of the word, but the very concept. They argue that without Serbian support, the idea of separate Macedonian conscience would have never prevailed. However, according to the supporters of Macedonism, every Serbian action was a well calculated move in the opposite direction.

After their unexpected defeat in Serbo-Bulgarian War of 1885, Serbia decisively determined her position on Macedonia. Propaganda in Macedonia was systematically expanded. Serbian ethnographers produced maps of Macedonia claiming that the Serbians made up the principal element in Macedonia . In 1886 the Saint Sava Association was set up, seeking to establish Serbian schools in Macedonia.

Serbian religious propaganda began to penetrate Macedonia from the middle of 1880s. It sought to substitute Bulgarian influence in central and northern Macedonia with their own. Serbia and Greece were natural allies in fighting the Bulgarian propaganda. This is plainly seen through an agreement accomplished between Pezas, the Greek Consul at Bitola and Ristich, the Serbian Consul. The agreement set that north of Prilep and Krushevo, the Serbian movement could act without obstruction, and the Serbs could rely on Greek support. South of Bitola, however, Serbian propaganda would be forbidden, but the Greek movement could rely on Serbian support. Lastly, in the region between Prilep, Krushevo and Bitola, ‘Greeks and Serbians would work together to subdue the Bulgarian movement . The recipient of Novakovich letter, Vladan Djordjevich was sent in 1891 to Athens as a Serbian envoy to propose joint action by Serbia and Greece against the Exarchate. .

From the beginning of 20th century, Serbian armed bands were sent to Macedonia under the direct control of Serbian government. . From 1905, Serbian armed bands were controlled by ‘Serbian Defense Chief Committee’ in Belgrade. Like the Greek bands, the Serbs also attempted to ‘encourage’ villages to abandon the Exarchate. For example, by April 1905, ‘they had persuaded twenty-four villages to petition for Patriarchistic registration’.

Newspapers published by Macedonian émigré communities in Serbia advocating an autonomous Macedonia or a distinct Macedonian conscience were banned from sale. B. Mokrov, and T. Gruevski, Pregled na Makedonskiot Pechat (1885–1992)

Whatever considerations Serbia had related to supporting Macedonism, their actions, until 1944 at least, when the People's Republic of Macedonia was established and there was active promotion of a distinct Macedonian identity, were aimed to complete suppression of distinctive Macedonian conscience and direct Serbianisation.

Quotes

About the term Macedonism

Nikolaĭ Genov and Anna Krŭsteva in their Recent Social Trends in Bulgaria, 1960-1995:

The third controversial trend in Bulgarian ethnic and national self-identification is towards Macedonization of ethnic Bulgarians. It is found among some ethnic Bulgarians in the Mt Pirin region. This is actually a typical ethnographic, i.e. pseudo-ethnic group. The number of Bulgarian citizens identifying themselves as "Macedonians" is insignificant. This is proved by the very limited membership of the ethno political parties advocating Macedonism in the country.

Serbian professor and politician Stojan Novakovich; excerpt of letter to Vladan Djordjevich, minister of education of Serbia, 1887:

Since the Bulgarian idea, as we all very well know, has deep roots in Macedonia, I think that it is impossible to exterminate it if we oppose to it the Serbian idea alone. I doubt that this idea will be able to suppress the Bulgarian idea as long as it is a mere confrontation. Therefore, we would greatly profit from an ally, sharply confronted with Bulgarianism, and including in itself elements that would attract the people and which would be intimate to his feelings - it is precisely they that will split it from Bulgarianism. This ally in my view is Macedonism, or in definite and wisely set boundaries, presentation of Macedonian dialect and Macedonian specifics. There is nothing more opposing to Bulgarian tendencies than this — there is no other situation where Bulgarians can find themselves in more unrest than against Macedonism.

Miodrag Drugovac, Друговац, Миодраг. Историjа на македонската книжевност ХХ век, 1990, a Socialist Republic of Macedonia of former Yugoslavia textbook

At this time of intense Bulgarian and Greek ecclesiastic and cultural propaganda, in Macedonia a new face of the Serbian ecclesiastic and cultural propaganda appears — Macedonism".

Drugovac, Друговац, Миодраг. Историjа на македонската книжевност ХХ век

Macedonism is an attempt at neutralization of the Bulgarian and Greek influences.

Jonathan Bousfield, Dan Richardson, Richard Watkins, in their The Rough Guide to Bulgaria 4:

...This led many young intellectuals in Vardar Macedonia to find solace in the ideology of Macedonism — which held that the Macedonian Slavs should not aspire to inclusion in the Bulgarian nation, but should aim for separate statehood within something approximating Gotse Delchev's original idea of a Balkan confederation. Many saw Macedonism as an ideology invented by the Serbs in order to break the unity of Bulgarians and Macedonians, but it did attract some notable adherents:...

Richard Gillespie in his Mediterranean Politics:

The only precondition laid down by Greece is that the FYROM repudiate the Communist concept of 'Macedonism' and toe the EU line. It would be a dreadful irony if, in the present post-communist era, the European Union granted a posteriori historical legitimacy to a communist idea. Furthermore, if the EU and the world community as a whole, through the UN, are anxious to recognize the 'Republic of Macedonia' in order to avert the risk of destabilization, they should be aware of the equally great risk of creating another trouble-spot in Greece. In either case, we must remember that, while voluble denials of territorial claims can be of purely momentary duration, the monopolizing of a name and/or symbol is a claim that can last for ever.

...and. ..

No international conciliatory or political legitimization of 'Macedonism' can hope to bring about a permanent resolution of the problem.

Loring Danforth, in his The Macedonian Conflict: ethnic nationalism in a transnational world:

According to the more extreme Macedonian nationalist position, modern Macedonians are not Slavs; they are the direct descendants of the ancient Macedonians, who were not Greeks. This claim is at least in part an attempt to refute the Greek claim that "Skopians" are Slavs and not Macedonians. According to extreme Macedonian nationalists "Slavism" is a destructive doctrine that "aims to eradicate Macedonism completely." If Macedonians are Slavs, then they "have no legal right to anything Macedonian"; they "legalize the robbery by the Greeks ." Macedonians should not allow the ancient Macedonians to be called Greek anymore than they would allow themselves to be called Greeks. Thus a unique Macedonian people —neither Slavic nor Greek— has existed in Macedonia since antiquity and continues to exist there now. The most powerful symbols of the continuity of Macedonian culture are "Alexander the Macedonian", as he is referred to in Macedonian sources; and the sun of the ancient Macedonian kings, which in 1992 was chosen as the flag of the newly independent Republic of Macedonia.

John D. Bell in The Radical Right in Central and Eastern Europe Since 1989 (edited by Sabrina P Ramet):

In addition to the phenomena described above, there has also arisen a new form of "Macedonism" that differs from the simple proposition that Macedonians are a distinct nationality. Having its origins, apparently, in émigré communities in Australia and Canada, this doctrine asserts that the ancient Macedonians were a pure Aryan people who migrated to Macedonia from India. Their language was the original "Slavic" tongue that was later learned by surrounding peoples who labored, "slaved," in the fields. The Greeks, "dark-skinned, Semitic" immigrants to the Balkans in the fifth century b.c., borrowed a form of the Macedonian alphabet, worshiped the Macedonian kings (the origin of the Greek pantheon), and borrowed/stole and then polluted Macedonian culture. Hellenism was originally not Greek, but "Macedonianism," spread through the known world by Alexander the Great. This form of "Macedonian fundamentalism" also predicts future unification of the separate parts of the Macedonian nation. While "orthodox" Macedonian nationalists have denounced the fundamentalists as "rabble ... neo-fascists, and even neo-Nazis," there are indications that their beliefs have attracted some followers in Macedonia itself and among separatists in the Pirin region (Blagoevgrad province).

About the term Macedonist

- "The Macedonian question has at last reached the public and the press. We say 'at last', because this question is not a new problem. We heard it from some people from Macedonia as long as about ten years ago. We first considered the words of those young patriots. .. of our not so serious disputes. We had also thought so until a year or two ago, when new discussions with some Macedonians showed us that the problem was not only vain words, but an idea that many would like to put into practice. And we were sorry and it was difficult for us to hear such words, because the problem seemed to us a highly delicate one, especially in the conditions in which we found ourselves. ..." - Petko Rachev Slaveykov, The Macedonian Question, published 18th January 1871 in the "Macedonia" newspaper in Constaninople.

- One of the earliest known references to the word "Macedonist" from the same article: "Some Macedonists distinguish themselves from the Bulgarians upon another basis -- they are pure Slavs, while the Bulgarians are Tartars and so on. .. In order to give credibility to their arbitrary view, the Macedonists point out the difference between the Macedonian and High Bulgarian dialects, of which the former is closer to the Slav language while the latter is mixed with Tartarisms, etc. " - Petko Rachev Slaveykov, The Macedonian Question, published 18th January 1871 in the "Macedonia" newspaper in Constaninople.

References

- ^ Nikolaĭ Genov, Anna Krŭsteva, (2001) Recent Social Trends in Bulgaria, 1960-1995, Page 74

- The "Mi-An" encyclopedia - a great victory for Macedonism

- See Evangelos Kofos

- ^ Jonathan Bousfield, Dan Richardson, Richard Watkins, (2002) The Rough Guide to Bulgaria 4, Rough Guides, ISBN 1858288827, Page 453

- ^ Richard Gillespie (1994) Mediterranean Politics, Page 99-100, Page 267

- ^ Loring Danforth (1995), The Macedonian Conflict: ethnic nationalism in a transnational world, Page 45

- ^ John D. Bell, edited by Sabrina P Ramet - (1999) The Radical Right in Central and Eastern Europe Since 1989, Page 252

- Isaija Mazhovski, Spomeni, Sofia, 1922

- А.Х.Халиков „Што сме ние: Бугари или Татари?

- GRIECHISCHE GESCHICHTE - von den Anfaengen bis zum Hellenismus, C.H.Beck oHG, Muenchen 1995; ISBN 3-406-45014-8

- J. Ronic, Prilozi za istoriju Srba u Ugarskoj u XVI, XVII и XVIII veku, Prva Knjiga, Matice srpske, br 25 - 26, Novi Sad , p. 52-53

- Makedonski pregled, IX, 2, 1934, p. 55; the original letter is kept in the Marin Drinov Museum in Sofia, and it is available for examination and study

- МАКЕДОНИЯ 1941, "Възкресението" - С. Нанев, 1941 г.

- Bulgarian Campaign Committees in Macedonia - 1941 Dimitre Michev

- "Зборник докумената и података о народоослободплачком рату jугословенских народа", т. VII, кн. 1, Борбе у Македониjи. Београд, 1952, с. XII и 22.

- Кои беа партизаните во Македонија-Никола Петров, Скопје, 1998

- СТЕНОГРАФСКИ БЕЛЕШКИ Тринаесеттото продолжение на Четиринаесеттата седница на Собранието на Република Македонија, 17 January, 2007

- КОЈ СО КОГО ЌЕ СЕ ПОМИРУВА - Лидерот на ВМРО-ДПМНЕ и Премиер на Република Македониjа, Љубчо Георгиевски одговара и полемизира на темата за национално помирување.

- ФОРУМ, "КАТАРАКТА", Ефтим Гашев

- D.M. Perry, The Politics of Terror - The Macedonian Liberation Movements 1893–1903, London, 1988, op. cit. p 19

- Veselinovic, 1886 , Karich 1887, Gopchevich 1889, Ivanic 1908

- Vakalopoulos, Modern History of Macedonia 1830-1912, Thessaloniki, 1988, pp. 184-185

- M.B. Petrovich, A History of Modern Serbia 1804–1918, New York, 1976, p. 497.

- B. Petrovich, op. cit. p. 546.

- D. Dakin, op. cit. p. 241

- Дипломатски архив — Дубровник, ПП одель., ф. I — 251/1888 г.

- ^ Друговац, Миодраг. Историjа на македонската книжевност ХХ век, Скопиje 1990, с. 73

See also

- Ethnic groups

- Languages

- History

- Demographic history of Macedonia

- History of the Republic of Macedonia

- Historical revisionism

- Macedonian Question

- IMRO

- Ilinden-Preobrazhenie Uprising

- National Liberation War of Macedonia

- Assimilation

| class="col-break " |

- Ideologies

- People

- Other

Notes

References

- Topolinjska, Z. (1998). "In place of a foreword: facts about the Republic of Macedonia and the Macedonian language" in International Journal of the Sociology of Language. Issue 131. pp. 1-11

External links

- Template:En icon Macedonia and Bulgarian National Nihilism

- Template:En icon Article on Macedonism

- Template:En icon Evangelos Kofos, "The Vision of a Greater Macedonia"

- Template:En icon Greece’s Macedonian Adventure: The Controversy over FYROM’s Independence and Recognition

- Template:En icon The Macedonian Question - an article published 18th January 1871 in the "Macedonia" newspaper in Constaninople by Petko Rachev Slaveykov

- Template:Bg icon Venko Markovski on Macedonism