| Revision as of 07:24, 6 December 2007 view sourceRandom user 39849958 (talk | contribs)19,517 edits Reverted good faith edits by Orangemarlin. using TW← Previous edit | Revision as of 07:25, 6 December 2007 view source Random user 39849958 (talk | contribs)19,517 edits you're right, this is what is says...Next edit → | ||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

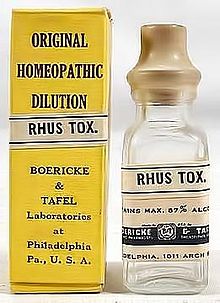

| Homeopathic remedies are based on substances that, in undiluted form, cause symptoms similar to the disease they aim to treat.<ref>{{cite news | title= Dynamization and Dilution | publisher= Creighton University Department of Pharmacology | url =http://altmed.creighton.edu/Homeopathy/philosophy/dilution.htm | accessdate = 2007-10-09 }}</ref> These substances are then diluted in a process of serial dilution, with shaking at each stage, that homeopaths believe removes side-effects but retains therapeutic powers - even past the point where no ]s of the original substance are likely to remain.<ref name="homsim">{{cite news | title= Similia similibus curentur (Like cures like) | publisher= Creighton University Department of Pharmacology | url =http://altmed.creighton.edu/Homeopathy/philosophy/similia.htm | accessdate = 2007-08-20 }}</ref> Hahnemann proposed that this process aroused and enhanced "spirit-like medicinal powers held within a drug".<ref> Samuel Hahnemann, combined 5th/6th edition</ref> Sets of remedies used in homeopathy are recorded in homeopathic ], with practitioners selecting treatments according to consultations that try to produce a picture of both the physical and psychological state of the patient. | Homeopathic remedies are based on substances that, in undiluted form, cause symptoms similar to the disease they aim to treat.<ref>{{cite news | title= Dynamization and Dilution | publisher= Creighton University Department of Pharmacology | url =http://altmed.creighton.edu/Homeopathy/philosophy/dilution.htm | accessdate = 2007-10-09 }}</ref> These substances are then diluted in a process of serial dilution, with shaking at each stage, that homeopaths believe removes side-effects but retains therapeutic powers - even past the point where no ]s of the original substance are likely to remain.<ref name="homsim">{{cite news | title= Similia similibus curentur (Like cures like) | publisher= Creighton University Department of Pharmacology | url =http://altmed.creighton.edu/Homeopathy/philosophy/similia.htm | accessdate = 2007-08-20 }}</ref> Hahnemann proposed that this process aroused and enhanced "spirit-like medicinal powers held within a drug".<ref> Samuel Hahnemann, combined 5th/6th edition</ref> Sets of remedies used in homeopathy are recorded in homeopathic ], with practitioners selecting treatments according to consultations that try to produce a picture of both the physical and psychological state of the patient. | ||

| ⚫ | Specific effects of homoeopathic remedies seem implausible <ref name="shang"/> and directly opposed to modern ] knowledge.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Ernst E |title=Is homeopathy a clinically valuable approach? |journal=Trends Pharmacol. Sci. |volume=26 |issue=11 |pages=547–8 |year=2005 |pmid=16165225}}; {{cite journal |author=Johnson T, Boon H |title=Where does homeopathy fit in pharmacy practice? |journal=American journal of pharmaceutical education |volume=71 |issue=1 |pages=7 |year=2007 |pmid=17429507 |url=http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pubmed&pubmedid=17429507}}</ref> Claims for the efficacy of homeopathy are unsupported by the collected weight of ] and ] studies.<ref name="brienlewithbryant">{{cite journal |author=Brien S, Lewith G, Bryant T |title=Ultramolecular homeopathy has no observable clinical effects. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled proving trial of Belladonna 30C |journal=British journal of clinical pharmacology |volume=56 |issue=5 |pages=562–568 |year=2003 |pmid=14651731 }}</ref><ref name="asthma">{{cite journal |author=McCarney RW, Linde K, Lasserson TJ |title=Homeopathy for chronic asthma |journal=Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) |issue=1 |pages=CD000353 |year=2004 |pmid=14973954 |doi=10.1002/14651858.CD000353.pub2 }}</ref><ref name="dementia">{{cite journal |author=McCarney R, Warner J, Fisher P, Van Haselen R |title=Homeopathy for dementia |journal=Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) |issue=1 |pages=CD003803 |year=2003 |pmid=12535487 }}; {{cite web|url=http://www.nhsdirect.nhs.uk/articles/article.aspx?articleId=197§ionId=27 |title=Homeopathy results |accessdate=2007-07-25 |publisher=] }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/category/13638.html |title=Report 12 of the Council on Scientific Affairs (A–97) |accessdate=2007-07-25 |publisher=] }}; {{cite journal |author=Linde K, Jonas WB, Melchart D, Willich S |title=The methodological quality of randomized controlled trials of homeopathy, herbal medicines and acupuncture |journal=International journal of epidemiology |volume=30 |issue=3 |pages=526–531 |year=2001 |pmid=11416076 }}; {{cite journal |title=Homeopathy for childhood and adolescence ailments: systematic review of randomized clinical trials |author=Altunç U, Pittler MH, Ernst E |journal=Mayo Clin Proc. |date=2007 |volume=82 |issue=1 |pages=69–75 |pmid= 17285788}}</ref> This lack of convincing evidence supporting its efficacy, along with its stance against modern scientific ideas, have caused homeopathy to be regarded as "] therapy at best and ] at worst" in the words of a recent medical review.<ref name=Ernst>{{cite journal |author=Ernst E, Pittler MH |title=Efficacy of homeopathic arnica: a systematic review of placebo-controlled clinical trials |journal=Archives of surgery (Chicago, Ill. : 1960) |volume=133 |issue=11 |pages=1187–90 |year=1998 |pmid=9820349}}</ref> Meta-analyses, which compare the results of many studies, face difficulty in controlling for the combination of ] and the fact that studies of homeopathy are generally flawed in design.<ref name="pmid11416076"/><ref name=pmid9310601>{{cite journal |author=Linde K, Clausius N, Ramirez G, ''et al'' |title=Are the clinical effects of homeopathy placebo effects? A meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials |journal=Lancet |volume=350 |issue=9081 |pages=834–43 |year=1997 |pmid=9310601}}</ref> However, a recent ] comparing homeopathic clinical trials with those of conventional medicines has shown that any effects are unlikely to be beyond that of placebo.<ref name="shang">{{cite journal |author=Shang A, Huwiler-Müntener K, Nartey L, ''et al'' |title=Are the clinical effects of homoeopathy placebo effects? Comparative study of placebo-controlled trials of homoeopathy and allopathy |journal=Lancet |volume=366 |issue=9487 |pages=726–732 |year=2005 |pmid=16125589 |doi=10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67177-2 }}</ref> Homeopaths are also accused of giving 'false hope' to patients who might otherwise seek effective conventional treatments. Many homeopaths advise against standard medical procedures such as vaccination,<ref>{{cite journal |author=Ernst E |title=Rise in popularity of complementary and alternative medicine: reasons and consequences for vaccination |journal=Vaccine |volume=20 Suppl 1 |issue= |pages=S90–3; discussion S89 |year=2001 |pmid=11587822}}</ref><ref name=pmid9243229/><ref name=pmid8554846/> and some homeopaths even advise against the use of ] drugs.<ref name=malaria1 /><ref name="pmid11082104" /><ref name=malaria2 /> | ||

| ⚫ | |||

| ==History== | ==History== | ||

Revision as of 07:25, 6 December 2007

Homeopathy (also homœopathy or homoeopathy; from the Greek ὅμοιος, hómoios, "similar" + πάθος, páthos, "suffering" or "disease") is a controversial form of complementary and alternative medicine first used in the late 18th century by German physician Samuel Hahnemann. His early work was advanced by later homeopaths such as James Tyler Kent, but Hahnemann's most famous textbook The Organon of the Healing Art remains in wide use today. The legal status of homeopathy varies from country to country, but homeopathic remedies are not tested and regulated under the same laws as conventional drugs. Usage is also variable and ranges from only two percent of people in Britain and the United States using homeopathy in any one year, to India, where homeopathy now forms part of traditional medicine and is used by approximately 15 percent of the population.

Homeopathic remedies are based on substances that, in undiluted form, cause symptoms similar to the disease they aim to treat. These substances are then diluted in a process of serial dilution, with shaking at each stage, that homeopaths believe removes side-effects but retains therapeutic powers - even past the point where no molecules of the original substance are likely to remain. Hahnemann proposed that this process aroused and enhanced "spirit-like medicinal powers held within a drug". Sets of remedies used in homeopathy are recorded in homeopathic materia medica, with practitioners selecting treatments according to consultations that try to produce a picture of both the physical and psychological state of the patient. Specific effects of homoeopathic remedies seem implausible and directly opposed to modern pharmaceutical knowledge. Claims for the efficacy of homeopathy are unsupported by the collected weight of scientific and clinical studies. This lack of convincing evidence supporting its efficacy, along with its stance against modern scientific ideas, have caused homeopathy to be regarded as "placebo therapy at best and quackery at worst" in the words of a recent medical review. Meta-analyses, which compare the results of many studies, face difficulty in controlling for the combination of publication bias and the fact that studies of homeopathy are generally flawed in design. However, a recent meta-analysis comparing homeopathic clinical trials with those of conventional medicines has shown that any effects are unlikely to be beyond that of placebo. Homeopaths are also accused of giving 'false hope' to patients who might otherwise seek effective conventional treatments. Many homeopaths advise against standard medical procedures such as vaccination, and some homeopaths even advise against the use of anti-malarial drugs.

History

Precursors

The "system of similars" emphasized in homeopathy was first described by doctors of the vitalist school of medicine, including the controversial Renaissance physician Paracelsus. Prior to the conception of homeopathy, Austrian physician Anton Freiherr von Störck and Scottish physician John Brown also held medical beliefs resembling those of Samuel Hahnemann, who is credited with the development of modern homeopathy in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

At the time of the inception of homeopathy, mainstream medicine employed such measures as bloodletting and purging, the use of laxatives and enemas, and the administration of complex mixtures, such as theriac, which was made from 64 substances including opium, myrrh, and viper's flesh. Such measures often worsened symptoms and sometimes proved fatal. While the virtues of these treatments had been extolled for centuries, Hahnemann rejected such methods as irrational and unadvisable. Instead, he favored the use of single drugs at lower doses and promoted an immaterial, vitalistic view of how living organisms function, believing that diseases have spiritual, as well as physical causes. (At the time, vitalism was part of mainstream science; in the twentieth century, however, medicine discarded vitalism, with the development of microbiology, the germ theory of disease, and advances in chemistry.) Hahnemann also advocated various lifestyle improvements to his patients, including exercise, diet, and cleanliness.

Hahnemann's conception of homeopathy

Samuel Hahnemann conceived of homeopathy while translating a medical treatise by Scottish physician and chemist William Cullen into German. He was skeptical of Cullen’s explanation of cinchona bark’s mechanism of action in treating malaria, so he decided to test its effects by taking it himself. Upon ingesting the bark, he experienced fever, shivering and joint pain, symptoms similar to those of malaria, which the bark was ordinarily used to treat. From this, Hahnemann came to believe that all effective drugs produce symptoms in healthy individuals similar to those of the diseases that they are intended to treat. This later became known as the "law of similars", the most important concept of homeopathy. The term "homeopathy" was coined by Hahnemann and first appeared in print in 1807, although he began outlining his theories of "medical similars" in a series of articles and monographs in 1796.

Hahnemann began to test the symptoms which substances can produce, a procedure which would later become known as "proving". The time-consuming tests required subjects to clearly record all of their symptoms as well as the ancillary conditions under which they appeared. Hahnemann used this data to find suitable substances for the treatment of particular diseases. The first collection of provings was published in 1805 and a second collection of 65 remedies appeared in the Materia Medica Pura in 1810. Hahnemann believed that large doses of things that caused similar symptoms would only aggravate illness, and so he advocated extreme dilutions of the substances. He devised a technique for making dilutions that he believed would preserve a substance's therapeutic properties while removing its harmful effects. He gathered and published a complete overview of his new medical system in his 1810 book, The Organon of the Healing Art, whose 6th edition, published in 1921, is still used by homeopaths today.

Rise to popularity and early criticism

During the 19th century homeopathy grew in popularity: in 1830, the first homeopathic schools opened, and throughout the 19th century dozens of homeopathic institutions appeared in Europe and the United States. Because of mainstream medicine's reliance on blood-letting and untested, often dangerous medicines, patients of homeopaths often had better outcomes than those of mainstream doctors. Homeopathic treatments, even if ineffective, would almost surely cause no harm, making the users of homeopathic medicine less likely to be killed by the medicine that was supposed to be helping them. The relative success of homeopathy in the 18th century may have led to the abandonment of the ineffective and harmful treatments of bloodletting and purging and to have begun the move towards more effective, scientific medicine.

In the early 19th century, homeopathy began to be criticized: Sir John Forbes, physician to Queen Victoria, said the extremely small doses of homeopathy were regularly derided as useless, laughably ridiculous and "an outrage to human reason." Professor Sir James Young Simpson said of the highly diluted drugs: "no poison, however strong or powerful, the billionth or decillionth of which would in the least degree affect a man or harm a fly." Nineteenth century American physician and author Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr. was also a vocal critic of homeopathy and published an essay in 1842 entitled Homœopathy, and its Kindred Delusions. The last school in the U.S. exclusively teaching homeopathy closed down in 1920.

General philosophy

Homeopathy is a vitalist philosophy in that it regards diseases and sickness to be caused by disturbances in a hypothetical vital force or life force in humans and that these disturbances manifest themselves as unique symptoms. Homeopathy contends that the vital force has the ability to react and adapt to internal and external causes, which homeopaths refer to as the "law of susceptibility". The law of susceptibility states that a negative state of mind can attract hypothetical disease entities called "miasms" to invade the body and produce symptoms of diseases, However, Hahnemann rejected the notion of a disease as a separate thing or invading entity and insisted that it was always part of the "living whole".

Law of similars

Hahnemann observed from his experiments with Cinchona bark, used as a treatment of malaria, that the side effects he experienced from the quinine in the Cinchona bark were similar to the symptoms of malaria. He reasoned that treatments for diseases must produce symptoms similar to of those disease being treated when taken by healthy individuals. From this Hahnemann conceived of the "law of similars", otherwise known as "like cures like" (Template:Lang-la). Hahnemann believed that by inducing artificial symptoms of a disease, the artificial symptoms would create another disturbance in the vital force thus pushing out the old disturbance and that the body would naturally recover from the artificially induced disturbance. The basic idea is that to cure a person suffering from an illness, one should administer a dilute dose of a substance that produces the same symptoms of the illness being treated in healthy individuals.

Miasms and disease

Hahnemann found as early as 1816 that his patients who he treated through homeopathy still suffered from chronic diseases that he was unable to cure. In 1828, he introduced the concept of miasms, which he regarded as underlying causes for many known diseases. A miasm is often defined by homeopaths as an imputed "peculiar morbid derangement of our vital force." Hahnemann associated each miasm with specific diseases, with each miasm seen as the root cause of several diseases. According to Hahnemann, initial exposure to miasms causes local symptoms, such as skin or venereal diseases, but if these symptoms are suppressed by medication, the cause goes deeper and begins to manifest itself as diseases of the internal organs. Homeopathy contends that treating diseases by directly opposing their symptoms, as is sometimes done in conventional medicine, is not so effective because all "disease can generally be traced to some latent, deep-seated, underlying chronic, or inherited tendency." The underlying imputed miasm still remains, and deep-seated ailments can only be corrected by removing the deeper disturbance of the vital force.

Hahnemann's miasm theory remains disputed and controversial within homeopathy even in modern times. In 1978, Anthony Campbell, then a consultant physician at The Royal London Homeopathic Hospital, criticized statements by George Vithoulkas claiming that syphilis, when treated with antibiotics, would develop into secondary and tertiary syphilis with involvement of the central nervous system. This conflicts with scientific studies, which indicate that penicillin treatment produces a complete cure of syphilis in more than 90% of cases. Campbell described this as "a thoroughly irresponsible statement which could mislead an unfortunate layman into refusing orthodox treatment" and said that it was not an isolated case, but part of a lengthy section arguing against conventional medicine. This echoes the idea in homeopathy that using medication to suppress the symptoms of a disease would only drive the underlying disease deeper into the body.

Originally Hahnemann presented only three miasms, of which the most important was "psora" (Greek for itch), described as being related to any itching diseases of the skin, supposed to be derived from suppressed scabies, and claimed to be the foundation of many further disease conditions. Hahnemann claimed psora to be the cause of such diseases as epilepsy, cancer, jaundice, deafness, and cataracts. Since Hahnemann's time, other miasms have been proposed, some replacing one or more of psora's proposed functions, including tubercular miasms and cancer miasms.

Development of remedies

Dilution and succussion

In producing treatments for diseases, homeopaths use a process called "dynamization" or "potentization" where the remedy is diluted into alcohol or water and then vigorously shaken by ten hard strikes against an elastic body in a process called "succussion". Hahnemann thought that the use of remedies which present symptoms similar to those of disease in healthy individuals would only intensify the symptoms and exacerbate the condition, so he advocated the dilution of the remedies to the point the symptoms were no longer experienced. During the process of potentization, homeopaths believe that the vital energy of the diluted substance is activated and its energy released by vigorous shaking of the substance. For this purpose, Hahnemann had a saddle maker construct a special wooden striking board covered in leather on one side and stuffed with horsehair. Insoluble solids, such as quartz and oyster shell, are diluted by grinding them with lactose (trituration).

Three potency scales are in regular use in homeopathy. Hahnemann pioneered and always favored the centesimal or "C scale", diluting a substance 1 part in a 100 of diluent at each stage. A 2C dilution is one where a substance is diluted to one part in one hundred, then one part of that diluted solution is diluted to one part in one hundred. This works out to one part of the original solution to ten thousand parts (100x100) of diluent. A 6C dilution repeats the process six times, ending up with one part in 1,000,000,000,000. (100x100x100x100x100x100, or 100) Other dilutions follow the same pattern. In homeopathy, a solution is described as higher potency the more dilute it is. Higher potencies - i.e. more dilute substances - are considered to be stronger deep-acting remedies.

Hahnemann advocated 30C dilutions for most purposes (a dilution by a factor of 10) and a common homeopathic treatment for the flu is a 200C dilution of duck liver, called Oscillococcinum in homeopathy. Comparing these levels of dilution to the number of molecules present in the initial solution, a 12C solution contains on average only about one molecule of the original substance. The chances of a single molecule of the original substance remaining in a 15C dilution would be roughly 1 in 2 million, and less than one in a billion billion billion billion (10) for a 30C solution. For a perspective on these numbers, there are in the order of 10 molecules of water in an Olympic size swimming pool and if such a pool were filled with a 15C homeopathic remedy, to expect to get a single molecule from the original substance, one would need to swallow 1% of the volume of such a pool, or roughly 25 metric tons of water.

For more perspective, 1ml of a solution which has gone through a 30C dilution would have been diluted into a volume of water equal to that of a cube of 1,000,000,000,000,000,000 meters per side, or about 106 light years. Thus, homeopathic remedies of the standard dilutions contain, with overwhelming probability, only water (or alcohol). Practitioners of homeopathy believe that this water retains some 'essential property' of the original substance, due to the shaking after each dilution. Hahnemann believed that the dynamization or shaking of the solution caused a "spirit like" healing force to be released from within the substance. He thought that even after every molecule of the previous substance has been removed from the water, the spiritual healing force still remained.

Some homeopaths developed a decimal scale (D or X), diluting the substance to ten times its original volume each stage. The D or X scale dilution is therefore half that of the same value of the C scale; for example, "12x" is the same level of dilution as "6C". Hahnemann never used this scale but it was very popular throughout the 19th century and still is in Europe. This potency scale appears to have been introduced in the 1830s by the American homeopath, Dr. Constantine Hering. In the last ten years of his life Hahnemann also developed a quintamillesimal (Q) or LM scale diluting the drug 1 part in 50,000 parts of diluent. A Q scale dilution is 2.35 times that of a C scale one, for example "20Q" is the same potency as "47C".

Not all homeopaths advocate extremely high dilutions. Many of the early homeopaths were originally doctors and generally tended to use lower dilutions such as "3x" or "6x", rarely going beyond "12x". A good example of this approach is that of Dr. Richard Hughes, who dismissed the extremely high dilutions as unnecessary. This was the dominant pattern in Europe throughout the 1820s to 1930s, but in America many practitioners developed and preferred the higher dilutions. This trend became especially exemplified by James Tyler Kent and dominated US homeopathy from the 1850s until its demise in the 1940s. The split between lower and higher dilutions also followed ideological lines with the former stressing pathology and a strong link to conventional medicine, while the latter emphasized vital force, miasms and a spiritual take on sickness. From a modern regulatory viewpoint, any product that contains detectable levels of active ingredients cannot be classified as a homeopathic remedy.

Provings

In order to determine which specific remedies could be used to treat which diseases, Hahnemann experimented on himself for several years as well as with patients. His experiments did not initially consist of giving remedies to the sick, because he thought that the most similar remedy, by virtue of its ability to induce symptoms similar to the disease itself, would make it impossible to determine which symptoms came from the remedy and which from the disease itself. Therefore, sick people were excluded from the provings. The method used for determining which remedies were suitable for specific diseases was called "proving". A homeopathic proving is the method by which the profile of a homeopathic remedy is determined. The word 'proving' derives from the German word 'Prüfung' meaning 'test'.

During the process of proving, Hahnemann used healthy volunteers who were given remedies, often in molecular doses, and the resulting symptoms were compiled by observers into a "Drug Picture". During the process the volunteers were observed for months at a time and were made to keep extensive journals detailing all of their symptoms at specific times during the day. During the tests volunteers were forbidden from consuming coffee, tea, spices, or wine. They were also not allowed to play chess, because Hahnemann considered it to be "too exciting", however they were allowed to drink beer and were encouraged to moderately exercise. After the experiments were over, Hahnemann made the volunteers offer their hands and take an oath swearing that what they reported in their journals was the truth, at which time he would interrogate them extensively concerning their symptoms.

Provings have been described as important in the development of the clinical trial, due to their early use of simple control groups, systematic and quantitative procedures, and some of the first application of statistics in medicine. The lengthy records of self-experimentation by homeopaths have occasionally proven useful in the development of modern drugs: For example, evidence nitroglycerin might be useful as a treatment for angina was discovered by looking through homeopathic provings, though homeopaths themselves never used it for that purpose at that time. The first recorded provings were published by Hahnemann in his 1796 Essay on a New Principle. His Fragmenta de viribus (1805) contained the results of 27 provings, and his 1810 Materia Medica Pura contained 65. 217 remedies underwent provings%2

- ^ "History of Homeopathy". Creighton University Department of Pharmacology. Retrieved 2007-07-23.

- Cite error: The named reference

tindleprevwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - Thomas K, Coleman P (2004). "Use of complementary or alternative medicine in a general population in Great Britain. Results from the National Omnibus survey". Journal of public health (Oxford, England). 26 (2): 152–7. PMID 15284318.

- Singh P, Yadav RJ, Pandey A (2005). "Utilization of indigenous systems of medicine & homoeopathy in India". Indian J. Med. Res. 122 (2): 137–42. PMID 16177471.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Dynamization and Dilution". Creighton University Department of Pharmacology. Retrieved 2007-10-09.

- "Similia similibus curentur (Like cures like)". Creighton University Department of Pharmacology. Retrieved 2007-08-20.

- Organon of Medicine, Samuel Hahnemann, combined 5th/6th edition

- ^ Shang A, Huwiler-Müntener K, Nartey L; et al. (2005). "Are the clinical effects of homoeopathy placebo effects? Comparative study of placebo-controlled trials of homoeopathy and allopathy". Lancet. 366 (9487): 726–732. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67177-2. PMID 16125589.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Ernst E (2005). "Is homeopathy a clinically valuable approach?". Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 26 (11): 547–8. PMID 16165225.; Johnson T, Boon H (2007). "Where does homeopathy fit in pharmacy practice?". American journal of pharmaceutical education. 71 (1): 7. PMID 17429507.

- Brien S, Lewith G, Bryant T (2003). "Ultramolecular homeopathy has no observable clinical effects. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled proving trial of Belladonna 30C". British journal of clinical pharmacology. 56 (5): 562–568. PMID 14651731.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - McCarney RW, Linde K, Lasserson TJ (2004). "Homeopathy for chronic asthma". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (1): CD000353. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000353.pub2. PMID 14973954.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - McCarney R, Warner J, Fisher P, Van Haselen R (2003). "Homeopathy for dementia". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (1): CD003803. PMID 12535487.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link); "Homeopathy results". National Health Service. Retrieved 2007-07-25. - "Report 12 of the Council on Scientific Affairs (A–97)". American Medical Association. Retrieved 2007-07-25.; Linde K, Jonas WB, Melchart D, Willich S (2001). "The methodological quality of randomized controlled trials of homeopathy, herbal medicines and acupuncture". International journal of epidemiology. 30 (3): 526–531. PMID 11416076.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link); Altunç U, Pittler MH, Ernst E (2007). "Homeopathy for childhood and adolescence ailments: systematic review of randomized clinical trials". Mayo Clin Proc. 82 (1): 69–75. PMID 17285788.{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Ernst E, Pittler MH (1998). "Efficacy of homeopathic arnica: a systematic review of placebo-controlled clinical trials". Archives of surgery (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 133 (11): 1187–90. PMID 9820349.

- Cite error: The named reference

pmid11416076was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - Linde K, Clausius N, Ramirez G; et al. (1997). "Are the clinical effects of homeopathy placebo effects? A meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials". Lancet. 350 (9081): 834–43. PMID 9310601.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Ernst E (2001). "Rise in popularity of complementary and alternative medicine: reasons and consequences for vaccination". Vaccine. 20 Suppl 1: S90–3, discussion S89. PMID 11587822.

- Cite error: The named reference

pmid9243229was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - Cite error: The named reference

pmid8554846was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - Cite error: The named reference

malaria1was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - Cite error: The named reference

pmid11082104was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - Cite error: The named reference

malaria2was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - "The Chemical Philosophy". U.S. National Library of Medicine. National Institutes of Health. 1998-04-27. Retrieved 2007-10-01.

- "About Homoeopathy". ccrhindia.org. Retrieved 2007-09-30.

- Federspil, Giovanni. "Letters, A critical overview of homeopathy" (PDF). Annals. Retrieved 2007-10-01.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - * Template:Harvard reference page 18

- Griffin, J. P., Venetian treacle and the foundation of medicines regulation (PDF), British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 58:3, Page 317. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2004.02147.x

- ^ Kaufman, Martin (1971-10-01). Homeopathy in America: The Rise and Fall of a Medical Heresy. The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0801812385.

- Wright, Iaian. "Shakespeare and Queens' (Part II)". Queens' College Cambridge. Retrieved 2007-10-14.

- ^ Lasagna, Louis. The doctors' dilemmas. Collier Books. p. 33.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Nicholls, Philip A. (March 1988). Homeopathy and the Medical Profession. Croom Helm Ltd. ISBN 978-0709918363.

- ^ Hahnemann, Dr Samuel (1818). Organon of medicine. Leipzig.

- Hahnemann, Samuel (1831). "Appeal to Thinking Philanthropist Respecting the Mode of Propagation of the Asiatic Choler". Retrieved 2007-08-13.

- Baxter AG (2001). "Louis Pasteur's beer of revenge". Nat. Rev. Immunol. 1 (3): 229–32. PMID 11905832.

- Coley NG (2004). "Medical chemists and the origins of clinical chemistry in Britain (circa [[1750]]–[[1850]])". Clin. Chem. 50 (5): 961–72. PMID 15105362.

{{cite journal}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help) - Ramberg PJ (2000). "The death of vitalism and the birth of organic chemistry: Wohler's urea synthesis and the disciplinary identity of organic chemistry". Ambix. 47 (3): 170–95. PMID 11640223.

- http://homeoint.org/books4/bradford/chapter35.htm Thomas L Bradford, The Life and Letters of Hahnemann, Ch.35

- Emmans Dean, Michael (2001). "Homeopathy and "the progress of science"" (PDF). History of science; an annual review of literature, research and teaching. 39 (125 Pt 3): 255–83. PMID 11712570. Retrieved 2007-10-02.

- ^ "Homeopathic Provings". Creighton University School of Medicine. Retrieved 2007-10-02.

- Kirschmann, Anne Taylor (December 2003). A Vital Force: Women in American Homeopathy. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0813533209.

- "Homeopathic Dynamization and Dilution". Creighton University School of Medicine. Retrieved 2007-10-02.

- Winston, Julian (2006). "Homeopathy Timeline". "The Faces of Homoeopathy". Whole Health Now. Retrieved 2007-07-23.

- Ernst E, Kaptchuk TJ (1996). "Homeopathy revisited". Arch. Intern. Med. 156 (19): 2162–4. PMID 8885813.

- Sir John Forbes, Homeopathy, Allopathy and Young Physic, London, 1846

- James Y Simpson, Homoeopathy, Its Tenets and Tendencies, Theoretical, Theological and Therapeutical, Edinburgh: Sutherland & Knox, 1853, 11

- Holmes, Oliver Wendell (1842). Homœopathy, and its Kindred Delusions; two lectures delivered before the Boston society for the diffusion of useful knowledge. Boston, MA: William D. Ticknor. OCLC 166600876. Found online at,Holmes, Oliver Wendell. "Homeopathy and Its Kindred Delusions". Retrieved 2007-07-25.

- Winston, Julian. "OUTLINE OF THE ORGANON". Retrieved 2007-08-04.

- Hahnemann, Samuel. "Organon Of Medicine". Retrieved 2007-08-04.

- David Little. "The Classical View on Miasms". Homeopathy Online. Retrieved 2007-10-12.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - The Chronic Diseases, their Nature and Homoeopathic Treatment, Dresden and Leipsic, Arnold. Vols. 1, 2, 3, 1828; vol. 4, 1830

- Samuel Hahnemann. "Organon, 5th edition, para 29". Homeopathy Home.com. Retrieved 2007-10-22.

- ^ "Miasms in homeopathy". Retrieved 2007-07-24.

- Dr J W Ward. "Taking the History of the Case". Pacific Coast Jnl of Homeopathy, July 1937. Retrieved 2007-10-22.

- "Cause of Disease in homeopathy". Creighton University Department of Pharmacology. Retrieved 2007-07-23.

- Birnbaum NR, Goldschmidt RH, Buffett WO (1999). "Resolving the common clinical dilemmas of syphilis". American family physician. 59 (8): 2233–40, 2245–6. PMID 10221308.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Critical review of The Science of Homeopathy from the British Homoeopathic Journal Volume 67, Number 4, October 1978

- "Online Museum". The Institute for the History of Medicine. Retrieved 2007-10-22.

- ^ "Dynamization and Dilution". Retrieved 2007-07-24.

- Resch, G, (1987). Scientific Foundations of Homoeopathy. Barthel & Barthel Publishing.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Robert, Ellis Dudgeon (1853). Lectures on the Theory & Practice of Homeopathy (PDF). London. pp. 526–7. ISBN 81-7021-311-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Little, David. "Hahnemann's Advanced Methods". Simillimum.com. Retrieved 2007-08-04.

- Edwin Wheeler, Charles (1941). Dr. Hughes: Recollections of Some Masters of Homeopathy. Health Through Homeopathy.

- Bodman, Frank (1970). he Richard Hughes Memorial Lecture. BHJ. pp. 179–193.

- Cuesta Laso LR, Alfonso Galán MT (2007). "Possible dangers for patients using homeopathy: may a homeopathic medicinal product contain active substances that are not homeopathic dilutions?". Medicine and law. 26 (2): 375–86. PMID 17639858.

- Dantas F, Fisher P, Walach H; et al. (2007). "A systematic review of the quality of homeopathic pathogenetic trials published from 1945 to 1995". Homeopathy : the journal of the Faculty of Homeopathy. 96 (1): 4–16. PMID 17227742.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Cassedy, James H. (June 1999). American Medicine and Statistical Thinking, 1800–1860. iUniverse. ISBN 978-1583484289.

- Fye WB (1986). "Nitroglycerin: a homeopathic remedy" (PDF). Circulation. 73 (1): 21–9. PMID 2866851.

- "Fragmenta de Viribus Medicamentorum Positivis Sive in sano Corpore Humano Observatis". Retrieved 2007-10-16.

{{cite web}}:|first=missing|last=(help) - Hahnemann, Samuel. "Materia Medica Pura". hpathy.com. Retrieved 2007-10-16.