| Revision as of 04:24, 16 March 2008 editFowler&fowler (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, File movers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers63,037 edits →Revenue settlements under the Company: adding ryotwari example picture← Previous edit | Revision as of 04:25, 16 March 2008 edit undoFowler&fowler (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, File movers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers63,037 edits + {{inuse}}Next edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{inuse}} | |||

| {{Infobox Former Country | {{Infobox Former Country | ||

| |native_name = | |native_name = | ||

Revision as of 04:25, 16 March 2008

| This article is actively undergoing a major edit for a little while. To help avoid edit conflicts, please do not edit this page while this message is displayed. This page was last edited at 04:25, 16 March 2008 (UTC) (16 years ago) – this estimate is cached, update. Please remove this template if this page hasn't been edited for a significant time. If you are the editor who added this template, please be sure to remove it or replace it with {{Under construction}} between editing sessions. |

| British India | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1757–1858 | |||||||

Flag

Flag | |||||||

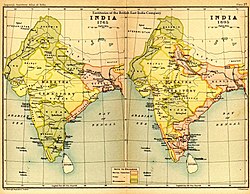

| India in the time of Clive at the onset of Company RuleIndia in the time of Clive at the onset of Company Rule | |||||||

| Status | British colony | ||||||

| Capital | Calcutta | ||||||

| Common languages | English and many others | ||||||

| Governor-General | |||||||

| • 1774-1775 | Warren Hastings | ||||||

| • 1857-1858 | The Viscount Canning | ||||||

| History | |||||||

| • Battle of Plassey | June 23 1757 | ||||||

| • Third Anglo-Maratha War | 1817-1818 | ||||||

| • Indian Rebellion | 1857 | ||||||

| • Government of India Act | August 2 1858 | ||||||

| Currency | British Indian rupee | ||||||

| ISO 3166 code | IN | ||||||

| |||||||

Company rule in India, also Company Raj ("raj," lit. "rule" in Sanskrit), or the rule of the British East India Company in India, was established after the Battle of Plassey in 1757, when the Nawab of Bengal surrendered his dominions to the British East India Company. The Company's rule in India lasted until 1858, when, consequent to the Government of India Act 1858, it was liquidated and the British Crown assumed direct control of the administration of India.

Expansion and territory

The British East India Company (hereafter, the Company) was founded in 1600, as The Company of Merchants of London Trading into the East Indies. It gained footing in India in 1612, after Mughal emperor Jahangir granted it the rights to establish a factory (a trading post) in Surat. In 1640, consequent to receiving similar permission from the local Vijayanagara ruler, a second factory was established in Madras. Soon, in 1668, the Company leased Bombay island, a former Portuguese outpost recently gifted to Great Britain in celebration of the wedding of Charles II of England to Catherine of Braganza. Thereafter, in 1687, the company moved its headquarters from Surat to Bombay. Next, in 1690, a Company settlement was established in Calcutta, again after receiving such rights from of the Mughal emperor, and the Company now began its lengthy and far-flung presence on the Indian subcontinent. During this time, other companies, established by the Portuguese, Dutch, French, and Danish, were similarly expanding in the region.

Although the British had earlier ruled in the factory areas, the beginning of British rule is often dated from the 1757 Battle of Plassey. Robert Clive's victory was consolidated in 1764 at the Battle of Buxar (in Bihar), where the emperor, Shah Alam II, was defeated. As a result, Shah Alam was coerced to appoint the company to be the diwan for the areas of Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa (this pretense of Mughal control was abandoned in 1827). The company thus became the supreme, but not the titular, power in much of the lower Gangetic plain, and company agents continued to trade on terms highly favorable to them. The Company also expanded from their bases at Bombay and Madras. The Anglo-Mysore Wars of 1766 to 1799 and the Anglo-Maratha Wars of 1772 to 1818 put the Company in control of most of India south of the Sutlej River.

The area controlled by the company expanded during the first three decades of the 19th century by two methods. The first was the use of subsidiary alliances between the British and the local rulers, under which control of foreign affairs, defense, and communications was transferred from the ruler to the Company, while the rulers retained limited dominion over internal affairs. This development created the Native States, or Princely States, of the Hindu maharaja and the Muslim nawabs. The second method was outright military conquest or direct annexation of territories; it was these annexed areas that were properly called British India. Most of northern India was annexed by the British.

At the turn of the 19th century, Governor-General Wellesley began what became two decades of accelerated expansion of Company territories. Prominent among the princely states were: Cochin (1791), Jaipur (1794), Travancore (1795), Hyderabad (1798), Mysore (1799), Cis-Sutlej Hill States (1815), Central India Agency (1819), Kutch and Gujarat Gaikwad territories (1819), Rajputana (1818), and Bahawalpur (1833). The annexed regions included the Northwest Provinces (comprising Rohilkhand, Gorakhpur, and the Doab) (1801), Delhi (1803), and Sindh (1843). Punjab, Northwest Frontier Province, and Kashmir, were annexed after the Anglo-Sikh Wars in 1849; however, Kashmir was immediately sold under the Treaty of Amritsar (1850) to the Dogra Dynasty of Jammu, and thereby became a princely state. In 1854 Berar was annexed, and the state of Oudh two years later.

The East India Company also signed treaties with Afghan rulers and with Ranjit Singh to counterbalance Russian support of Persian plans in western Afghanistan. In 1839 the Company's actions brought about the First Afghan War (1839-42). However, as the British expanded their territory in India, so did Russia in Central Asia, with the taking of Bukhara and Samarkand in 1863 and 1868 respectively, thereby setting the stage for the Great Game of Central Asia.

Policies

The British Parliament enacted a series of laws (see British East India Company), beginning with the Regulating Act of 1773 which put limits on the Company's commercial activities as well as control over acquired territory. Limiting the company charter to periods of twenty years, subject to review upon renewal, the 1773 act gave the British government supervisory rights over the Bengal, Bombay, and Madras presidencies. The Regulating Act also created a unified administration for India, uniting the three presidencies under the authority of the Bengal's governor, who was elevated to the new position of Governor-General. Warren Hastings was the first incumbent (1773-1785). The India Act of 1784 sometimes described as the "half-loaf system," as it sought to mediate between Parliament and the company directors, enhanced Parliament's control by establishing the Board of Control, whose members were selected from the cabinet.

In the Charter Act of 1813, the British parliament renewed the Company's charter but terminated its monopoly, opening India both to private investment and missionaries. With increased British power in India supervision of Indian affairs by the British Crown and parliament increased as well; by the 1820s British nationals could transact business or engage in missionary work under the protection of the Crown in the three Company presidencies. With the Charter Act of 1833, the British parliament revoked the Company's trade license completely, making the Company a part of British governance, although the administration of British India remained the province of Company officers. The Charter Act also recognized British moral responsibility for introducing "just and humane" laws in India, foreshadowing future social legislation, and outlawing a number of traditional practices such as sati and thagi (or thuggee, robbery coupled with ritual murder). The Charter Act of 1833 deprived the presidencies of the power to make laws, concentrating legislative power with the Governor-General and his council.

Revenue settlements under the Company

| This article or section is in a state of significant expansion or restructuring. You are welcome to assist in its construction by editing it as well. If this article or section has not been edited in several days, please remove this template. If you are the editor who added this template and you are actively editing, please be sure to replace this template with {{in use}} during the active editing session. Click on the link for template parameters to use.

This article was last edited by Fowler&fowler (talk | contribs) 16 years ago. (Update timer) |

In the remnant of the Mughal revenue system existing in pre-1765 Bengal, zamindars collected revenue on behalf of the Mughal emperor, whose representative, or diwan supervised their activities closely, with the stated goal of moderation in assessment. On being awarded the diwani or overlordship of Bengal following the Battle of Buxar in 1764, the East India Company found itself short of trained administrators, especially those familiar with local custom and law; tax collection was consequently farmed out. However, following the devastating famine of 1770, the importance of oversight of revenue officials was understood by the Company officials in Calcutta.

In 1772, under Warren Hastings, the East India Company took over revenue collection directly in the Bengal Presidency (then Bengal and Bihar), establishing a Board of Revenue with offices in Calcutta and Patna, and moving the pre-existing Mughal revenue records from Murshidabad to Calcutta. In 1773, after Oudh ceded the tributary state of Benaras, the revenue collection system was extended to the territory with a Company Resident in charge. The following year—with a view to preventing corruption—Company district collectors, who were then responsible for revenue collection for an entire district, were replaced with provincial councils at Patna, Murshidabad, and Calcutta, and with Indian collectors working within each district. The title, "collector," reflected "the centrality of land revenue collection to government in India: it was the government's primary function and it moulded the institutions and patterns of administration."

The Company inherited a revenue collection system from the Mughals in which the heaviest proportion of the tax burden fell on the cultivators, with one-third of the production reserved for imperial entitlement; this pre-colonial system became the Company revenue policy's baseline. However, there was vast variation across India in the methods by which the revenues were collected; with this complication in mind, a Committee of Circuit toured the districts of expanded Bengal presidency in order to make a five-year settlement, consisting of five-yearly inspections and temporary tax farming. In their overall approach to revenue policy, Company officials were guided by two goals: first, preserving as much as possible the balance of rights and obligations that were traditionally claimed by the farmers who cultivated the land and the various intermediaries who collected tax on the state's behalf and who reserved a cut for themselves; and second, identifying those sectors of the rural economy that would maximize both revenue and security. Although their first revenue settlement turned out to be essentially the same as the more informal pre-existing Mughal one, the Company had created a foundation for the growth of both information and bureaucracy.

In 1793, the new Governor-General, Lord Cornwallis, promulgated the permanent settlement of land revenues in the presidency, the first socio-economic regulation in colonial India. It was named permanent because it fixed the land tax in perpetuity in return for landed property rights for zamindars; it simultaneously defined the nature of land ownership in the presidency, and gave individuals and families separate property rights in occupied land. Over the next century, partly as a result of land surveys, court rulings, and property sales, the change was given practical dimension. An influence on the development of this revenue policy were the economic theories then current, which regarded agriculture as the engine of economic development, and consequently stressed the fixing of revenue demands in order to encourage growth. The expectation behind the permanent settlement was that knowledge of a fixed government demand would encourage the zamindars to increase both their average outcrop and the land under cultivation, since they would be able to retain the profits from the increased output; in addition, it was envisaged that land itself would become a marketable form of property that could be purchased, sold, or mortgaged. A feature of this economic rationale was the additional expectation that the zamindars, recognizing their own best interest, would not make unreasonable demands on the peasantry.

However, these expectations were not realized in practice, and in many regions of Bengal, the peasants bore the brunt of the increased demand, there being little protection for their traditional rights in the new legislation. Forced labor of the peasants by the zamindars became more prevalent as cash crops were cultivated to meet the Company revenue demands. Although commercialized cultivation was not new to the region, it had now penetrated deeper into village society and made it more vulnerable to market forces. The zamindars themselves were often unable to meet the increased demands that the Company had placed on them; consequently, many defaulted, and by one estimate, up to one-third of their lands were auctioned during the first three decades following the permanent settlement. The new owners were often Brahmin and Kayastha employees of the Company who had a good grasp of the new system, and, in many cases, had prospered under it.

Since the zamindars were never able to undertake costly improvements to the land envisaged under the Permanent Settlement, some of which required the removal of the existing farmers, they soon became rentiers who lived off the rent from their tenant farmers. In many areas, especially northern Bengal, they had to increasingly share the revenue with intermediate tenure holders, called jotedars, who supervised farming in the villages. Consequently, unlike the contemporaneous Enclosure movement in Britain, agriculture in Bengal remained the province of the subsistence farming of innumerable small paddy fields.

The zamindari system was one of three principal revenue settlements that were employed by the Company in India. In southern India, Thomas Munro, who would later become Governor of Madras, promoted the ryotwari system, in which the government settled land-revenue directly with the peasant farmers, or ryots. This was, in part, a consequence of the turmoil of the Anglo-Mysore Wars, which had prevented the emergence of a class of large landowners; in addition, Munro and others felt that ryotwari was closer to traditional practice in the region and ideologically more progressive, allowing the benefits of Company rule to reach the lowest levels of rural society. The keystone of the new system of temporary settlements was the classification of agricultural fields according to soil type and produce, with average rent rates fixed for the period of the settlement. However, in spite of the appeal of the ryotwari system's abstract principles, class hierarchies in southern Indian villages had not entirely disappeared, and peasant cultivators sometimes came to experience revenue demands they could not meet. In the 1850s, a scandal erupted when it was discovered that some Indian revenue agents of the Company were using torture to meet the Company's revenue demands.

Trade: 1770-1860

Neither the zamindari nor the ryotwari systems proved effective in the long run because India was integrated into an international economic and pricing system over which it had no control, while increasing numbers of people subsisted on agriculture for lack of other employment. Millions of people involved in the heavily taxed Indian textile industry also lost their markets, as they were unable to compete successfully with cheaper textiles produced in Lancashire's mills from Indian raw materials.

Law

Beginning with the Mayor's Court, established in 1727 for civil litigation in Bombay, Calcutta, and Madras, justice in the interior came under the company's jurisdiction. In 1772 an elaborate judicial system, known as adalat, established civil and criminal jurisdictions along with a complex set of codes or rules of procedure and evidence. Both Hindu pandits and Muslim qazis (sharia court judges) were recruited to aid the presiding judges in interpreting their customary laws, but in other instances, British common and statutory laws became applicable. In extraordinary situations where none of these systems was applicable, the judges were enjoined to adjudicate on the basis of "justice, equity, and good conscience." The legal profession provided numerous opportunities for educated and talented Indians who were unable to secure positions in the company, and, as a result, Indian lawyers later dominated nationalist politics and reform movements.

Education

Education for the most part was left to the charge of Indians or to private agents who imparted instruction in the vernaculars. But in 1813, the British became convinced of their "duty" to awaken the Indians from intellectual slumber by exposing them to British literary traditions, earmarking a paltry sum for the cause. Controversy between two groups of Europeans - the "Orientalists" and "Anglicists" - over how the money was to be spent prevented them from formulating any consistent policy until 1835 when William Cavendish Bentinck, the governor-general from 1828 to 1835, finally broke the impasse by resolving to introduce the English language as the medium of instruction. English replaced Persian in public administration and education.

Social Reform

The company's education policies in the 1830s tended to reinforce existing lines of socioeconomic division in society rather than bringing general liberation from ignorance and superstition. Whereas the Hindu English-educated minority spearheaded many social and religious reforms either in direct response to government policies or in reaction to them, Muslims as a group initially failed to do so, a position they endeavored to reverse. Western-educated Hindu elites sought to rid Hinduism of its much criticized social evils: the caste system, child marriage, and sati. Religious and social activist Ram Mohan Roy (1772-1833), who founded the Brahmo Samaj (Society of Brahma) in 1828, displayed a readiness to synthesize themes taken from Christianity, Deism, and Indian monism, while other individuals in Bombay and Madras initiated literary and debating societies that gave them a forum for open discourse. The exemplary educational attainments and skillful use of the press by these early reformers enhanced the possibility of effecting broad reforms without compromising societal values or religious practices.

Infrastructure Development

The 1850s witnessed the introduction of the three "engines of social improvement" that heightened the British illusion of permanence in India. They were the railroads, the telegraph, and the uniform postal service, inaugurated during the tenure of Dalhousie as governor-general. The first railroad lines were built in 1850 from Howrah (Haora, across the Hughli River from Calcutta) inland to the coalfields at Raniganj, Bihar, a distance of 240 kilometers. In 1851 the first electric telegraph line was laid in Bengal and soon linked Agra, Bombay, Calcutta, Lahore, Varanasi, and other cities. The three different presidency or regional postal systems merged in 1854 to facilitate uniform methods of communication at an all-India level. With uniform postal rates for letters and newspapers - one-half anna and one anna, respectively (sixteen annas equalled one rupee) - communication between the rural and the metropolitan areas became easier and faster. The increased ease of communication and the opening of highways and waterways accelerated the movement of troops, the transportation of raw materials and goods to and from the interior, and the exchange of commercial information.

The railroads did not break down the social or cultural distances between various groups but tended to create new categories in travel. Separate compartments in the trains were reserved exclusively for the ruling class, separating the educated and wealthy from ordinary people. Similarly, when the Sepoy Rebellion was quelled in 1858, a British official exclaimed that "the telegraph saved India." He envisaged, of course, that British interests in India would continue indefinitely.

Features of Company Rule

See also

- British Raj

- Secretary of State for India

- Governor-General of India

- Government of India Act

- History of Bangladesh

- History of India

- History of Pakistan

References

- ^ Ludden 2002, p. 133 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFLudden2002 (help)

- Ludden 2002, p. 135 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFLudden2002 (help)

- Ludden 2002, p. 134 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFLudden2002 (help)

- ^ Robb 2002, pp. 126–129 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFRobb2002 (help)

- Brown 1994, p. 55 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFBrown1994 (help)

- ^ Peers 2006, pp. 45–47 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFPeers2006 (help)

- Peers 2006, pp. 45–47 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFPeers2006 (help), Robb 2002, pp. 126–129 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFRobb2002 (help)

- Robb 2002, p. 127 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFRobb2002 (help)

- Guha 1995 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFGuha1995 (help)

- ^ Bose 1993 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFBose1993 (help)

- Tomlinson 1993, p. 43 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFTomlinson1993 (help)

- ^ Metcalf & Metcalf 2006, p. 79 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFMetcalfMetcalf2006 (help)

- Roy 2000, pp. 37–42 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFRoy2000 (help)

- ^ Peers 2006, p. 47 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFPeers2006 (help)

- Robb 2002, p. 128 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFRobb2002 (help)

Contemporary General Histories

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

Monographs and Collections

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference.

Articles in Journals or Collections

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference

Classic Histories

- India Pakistan

This image is available from the United States Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division under the digital ID {{{id}}}

This tag does not indicate the copyright status of the attached work. A normal copyright tag is still required. See Misplaced Pages:Copyrights for more information.