| Revision as of 19:27, 22 August 2008 edit96.229.193.68 (talk)No edit summary← Previous edit | Revision as of 14:24, 6 September 2008 edit undoCoppertwig (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers17,262 edits Adding links to citations. Semi-automated edit using a Perl script. Please contact me on my talk page with any comments or problems.Next edit → | ||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

| |place=], ] | |place=], ] | ||

| |result=Coup attempt crushed | |result=Coup attempt crushed | ||

| |combatant1=<!-- Deleted image removed: ] -->] (ARVN) rebels |

|combatant1=<!-- Deleted image removed: ] -->] (ARVN) rebels | ||

| |combatant2=]]<br /><!-- Deleted image removed: ] -->] (ARVN) loyalists |

|combatant2=]]<br /><!-- Deleted image removed: ] -->] (ARVN) loyalists | ||

| |commander1=]<br />] | |commander1=]<br />] | ||

| |commander2=]<br />] | |commander2=]<br />] | ||

| Line 22: | Line 22: | ||

| The revolt was led by 28-year-old Lieutenant Colonel ],<Ref name="j117"/> a northerner who had fought with the ] forces against the ] during the ]. Later trained at ] in the ], Dong was regarded by American military advisers as a brilliant tactician and the brightest military prospect of his generation.<Ref name="j117"/> Back in Vietnam, Dong became discontented with Diem's arbitrary rule and constant meddling in the internal affairs of the army. Diem promoted officers on loyalty rather than skill, and played senior officers against one another in order to weaken the military leadership and prevent them from challenging his rule. Years after the coup, Dong asserted that his sole objective was to force Diem to improve the governance of the country.<Ref name="k"/> Dong was clandestinely supported by his brother-in-law Lieutenant Colonel Nguyen Trieu Hong and Hong's uncle Hoang Co Thuy.<Ref name="h131"/> | The revolt was led by 28-year-old Lieutenant Colonel ],<Ref name="j117"/> a northerner who had fought with the ] forces against the ] during the ]. Later trained at ] in the ], Dong was regarded by American military advisers as a brilliant tactician and the brightest military prospect of his generation.<Ref name="j117"/> Back in Vietnam, Dong became discontented with Diem's arbitrary rule and constant meddling in the internal affairs of the army. Diem promoted officers on loyalty rather than skill, and played senior officers against one another in order to weaken the military leadership and prevent them from challenging his rule. Years after the coup, Dong asserted that his sole objective was to force Diem to improve the governance of the country.<Ref name="k"/> Dong was clandestinely supported by his brother-in-law Lieutenant Colonel Nguyen Trieu Hong and Hong's uncle Hoang Co Thuy.<Ref name="h131"/> | ||

| Many Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) officers were members of other anti-communist nationalist groups that were opposed to Diem, such as the ] (''Nationalist Party of Greater Vietnam'') and the ] (VNQDD, ''Vietnamese Nationalist Party''), which were both established before ]. The VNQDD had run a military academy in ] near the ] border with the assistance of their nationalist Chinese counterparts, the ]. Diem and his family had crushed all alternative anti-communist nationalists, and his politicisation of the army had alienated the servicemen. Officers were promoted on the basis of political allegiance rather than competence, meaning that many VNQDD and Dai Viet trained officers were denied such promotions.< |

Many Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) officers were members of other anti-communist nationalist groups that were opposed to Diem, such as the ] (''Nationalist Party of Greater Vietnam'') and the ] (VNQDD, ''Vietnamese Nationalist Party''), which were both established before ]. The VNQDD had run a military academy in ] near the ] border with the assistance of their nationalist Chinese counterparts, the ]. Diem and his family had crushed all alternative anti-communist nationalists, and his politicisation of the army had alienated the servicemen. Officers were promoted on the basis of political allegiance rather than competence, meaning that many VNQDD and Dai Viet trained officers were denied such promotions.<ref name="hback">], pp. 131–133.</ref> | ||

| Planning for the coup had gone on for over a year, with Dong recruiting disgruntled officers. This included his commander, Colonel ]. In 1955, Thi had fought for Diem against the ] ] in the ] in 1955. This performance so impressed Diem that the president thereafter referred to Thi as "my son".<ref name = "j117"/> The coup was organised with the help of some VNQDD and Dai Viet members, civilians and officers alike.<Ref name="h131"/> Dong enlisted the cooperation of an armoured regiment, marine unit and three paratrooper battalions. The operation was scheduled to launch on November 11 at 05:00.<Ref name="k"/><ref name="h131"/> | Planning for the coup had gone on for over a year, with Dong recruiting disgruntled officers. This included his commander, Colonel ]. In 1955, Thi had fought for Diem against the ] ] in the ] in 1955. This performance so impressed Diem that the president thereafter referred to Thi as "my son".<ref name = "j117"/> The coup was organised with the help of some VNQDD and Dai Viet members, civilians and officers alike.<Ref name="h131"/> Dong enlisted the cooperation of an armoured regiment, marine unit and three paratrooper battalions. The operation was scheduled to launch on November 11 at 05:00.<Ref name="k"/><ref name="h131"/> | ||

| Line 28: | Line 28: | ||

| == Coup == | == Coup == | ||

| According to ], the ]-winning author of ''Vietnam: A History'', the coup was ineffectively executed;<Ref name="k"/> although the rebels captured the headquarters of the Joint General Staff at ],<ref name="h131"/> they failed to follow the textbook tactics of blocking the roads leading into ]. They also failed to disconnect phone lines into the Palace, which allowed Diem to call for aid from loyal units. At first, the forces encircled the compound without attacking, believing that Diem would comply with their demands. Dong attempted to call on US ambassador ] to put pressure on Diem. Durbrow, although a critic of Diem, maintained his government's position of supporting Diem, stating "We support this government until it fails".<ref name="k">Karnow, pp. 252–253.</ref> Most of the rebel soldiers had been told that they were attacking in order to save Diem from a mutiny by the Presidential Guard. Only one or two officers in any given rebel unit knew the true situation.<Ref name="h131"/> | According to ], the ]-winning author of ''Vietnam: A History'', the coup was ineffectively executed;<Ref name="k"/> although the rebels captured the headquarters of the Joint General Staff at ],<ref name="h131"/> they failed to follow the textbook tactics of blocking the roads leading into ]. They also failed to disconnect phone lines into the Palace, which allowed Diem to call for aid from loyal units. At first, the forces encircled the compound without attacking, believing that Diem would comply with their demands. Dong attempted to call on US ambassador ] to put pressure on Diem. Durbrow, although a critic of Diem, maintained his government's position of supporting Diem, stating "We support this government until it fails".<ref name="k">], pp. 252–253.</ref> Most of the rebel soldiers had been told that they were attacking in order to save Diem from a mutiny by the Presidential Guard. Only one or two officers in any given rebel unit knew the true situation.<Ref name="h131"/> | ||

| The paratroopers' first assault on the palace met with surprising resistance. Only thirty Presidential Guardsmen stood between the rebels and Diem, but they managed to repel the initial thrust and kill seven rebels who attempted to scale palace walls. The rebels cordoned off the palace and held fire.<ref name="j117"/> | The paratroopers' first assault on the palace met with surprising resistance. Only thirty Presidential Guardsmen stood between the rebels and Diem, but they managed to repel the initial thrust and kill seven rebels who attempted to scale palace walls. The rebels cordoned off the palace and held fire.<ref name="j117"/> | ||

| At daybreak, civilians began massing outside the palace gates, verbally encouraging the rebels and waving banners advocating regime change. Saigon Radio announced that a "Revolutionary Council" was in charge of South Vietnam’s government. Diem appeared lost, while many Saigon-based ARVN troops rallied to the insurgents. According to Nguyen Thai Binh, an exiled political rival, "Diem was lost. Any other than he would have capitulated."<Ref name="j117"/> However, the rebels hesitated as they decided their next move. Dong felt that the rebels should take the opportunity of storming the palace and capturing Diem. Thi on the other hand, was worried that Diem could be killed in an attack. Thi felt that despite Diem's shortcomings, the president was South Vietnam's best available leader, believing that enforced reform would yield the best outcome.<ref name = "j118"/> The rebels wanted ], Diem's younger brother and his chief adviser, and his wife out of the government, although they disagreed over whether to kill or deport the couple.<ref name="j117">Jacobs, p. 117.</ref> | At daybreak, civilians began massing outside the palace gates, verbally encouraging the rebels and waving banners advocating regime change. Saigon Radio announced that a "Revolutionary Council" was in charge of South Vietnam’s government. Diem appeared lost, while many Saigon-based ARVN troops rallied to the insurgents. According to Nguyen Thai Binh, an exiled political rival, "Diem was lost. Any other than he would have capitulated."<Ref name="j117"/> However, the rebels hesitated as they decided their next move. Dong felt that the rebels should take the opportunity of storming the palace and capturing Diem. Thi on the other hand, was worried that Diem could be killed in an attack. Thi felt that despite Diem's shortcomings, the president was South Vietnam's best available leader, believing that enforced reform would yield the best outcome.<ref name = "j118"/> The rebels wanted ], Diem's younger brother and his chief adviser, and his wife out of the government, although they disagreed over whether to kill or deport the couple.<ref name="j117">], p. 117.</ref> | ||

| ] (pictured left).]] | ] (pictured left).]] | ||

| Thi demanded that Diem appoint an officer as Prime Minister and that Diem remove ] from the palace. Saigon Radio broadcast a speech authorised by Thi's Revolutionary Council, claiming that Diem was being removed because he was corrupt and suppressed liberty. Worried by the uprising, Diem sent his private secretary ] to negotiate with the coup leaders.<ref name="l">Langguth, pp. 108–109.</ref> |

Thi demanded that Diem appoint an officer as Prime Minister and that Diem remove ] from the palace. Saigon Radio broadcast a speech authorised by Thi's Revolutionary Council, claiming that Diem was being removed because he was corrupt and suppressed liberty. Worried by the uprising, Diem sent his private secretary ] to negotiate with the coup leaders.<ref name="l">], pp. 108–109.</ref> | ||

| ], became the rebels' spokesman. The most prominent political critic of Diem, Dan had been disqualified from the ] after winning his seat by a ratio of 6:1 despite Diem having organised votestacking against him. He cited political mismanagement of the war against the Vietcong the government's refusal to broaden its political base as the reason for the revolt.<ref name="j118"/> |

], became the rebels' spokesman. The most prominent political critic of Diem, Dan had been disqualified from the ] after winning his seat by a ratio of 6:1 despite Diem having organised votestacking against him. He cited political mismanagement of the war against the Vietcong the government's refusal to broaden its political base as the reason for the revolt.<ref name="j118"/> | ||

| Madame Nhu railed against Diem agreeing to a power-sharing arrangement, asserting that it was the destiny of Diem and his family to save the country.<ref name="l"/> During the standoff, Durbrow ambivalently noted "We consider it overriding importance to Vietnam and Free World that agreement be reached soonest in order avoid continued division, further bloodshed with resultant fatal weakening Vietnam’s ability resist communists."<ref name="h131">Hammer, p. 131.</ref> | Madame Nhu railed against Diem agreeing to a power-sharing arrangement, asserting that it was the destiny of Diem and his family to save the country.<ref name="l"/> During the standoff, Durbrow ambivalently noted "We consider it overriding importance to Vietnam and Free World that agreement be reached soonest in order avoid continued division, further bloodshed with resultant fatal weakening Vietnam’s ability resist communists."<ref name="h131">], p. 131.</ref> | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| In the meantime, the negotiations allowed time for loyalists to enter Saigon and rescue the president. The Fifth Division of Colonel ], a future president, brought infantry forces from ], a town north of Saigon. The Seventh Division of Colonel ] brought in tanks from ], a town in the ] south of Saigon.<ref name="j118"/> Diem promised to end press censorship, liberalise the economy, and hold free and fair elections. Diem refused to sack Nhu, but he agreed to dissolve his cabinet and form a government that would accommodate the Revolutionary Council. In the early hours of November 12, Diem taped a speech detailing the concessions, which the rebels broadcast on Saigon Radio.<ref name="j118">Jacobs, p. 118.</ref> | In the meantime, the negotiations allowed time for loyalists to enter Saigon and rescue the president. The Fifth Division of Colonel ], a future president, brought infantry forces from ], a town north of Saigon. The Seventh Division of Colonel ] brought in tanks from ], a town in the ] south of Saigon.<ref name="j118"/> Diem promised to end press censorship, liberalise the economy, and hold free and fair elections. Diem refused to sack Nhu, but he agreed to dissolve his cabinet and form a government that would accommodate the Revolutionary Council. In the early hours of November 12, Diem taped a speech detailing the concessions, which the rebels broadcast on Saigon Radio.<ref name="j118">], p. 118.</ref> | ||

| As the speech was being aired, two infantry divisions and supporting loyal armour approached the palace grounds. Some of the Saigon-based units that had joined the rebellion sensed that Diem had regained the upper hand and switched sides for the second time in two days. The paratroopers became outnumbered and were forced to retreat to defensive positions around their barracks, which were approximately {{convert|1|km|mi}} away.<ref name="j118"/> After a brief but violent battle that killed around 400 people, the coup attempt was crushed.<Ref name="l"/> | As the speech was being aired, two infantry divisions and supporting loyal armour approached the palace grounds. Some of the Saigon-based units that had joined the rebellion sensed that Diem had regained the upper hand and switched sides for the second time in two days. The paratroopers became outnumbered and were forced to retreat to defensive positions around their barracks, which were approximately {{convert|1|km|mi}} away.<ref name="j118"/> After a brief but violent battle that killed around 400 people, the coup attempt was crushed.<Ref name="l"/> | ||

| General ], commander of the ARVN II Corps, climbed over the palace wall to reach Diem on the second day of the siege. His action gained him a reputation of having helped the president, but in later years he was criticised for having a foot in both camps. Critics claimed that Khanh had been on good terms with the rebels and decided against rebelling when it was clear that Diem would win.<ref name="h132">Hammer, p. 132.</ref> | General ], commander of the ARVN II Corps, climbed over the palace wall to reach Diem on the second day of the siege. His action gained him a reputation of having helped the president, but in later years he was criticised for having a foot in both camps. Critics claimed that Khanh had been on good terms with the rebels and decided against rebelling when it was clear that Diem would win.<ref name="h132">], p. 132.</ref> | ||

| == Aftermath == | == Aftermath == | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| After the failed coup, Dong and Thi fled to ], where they were given asylum by Prince ].<ref name="h132"/> Diem promptly reneged on his promises, and began rounding up scores of critics, including several former cabinet ministers and some of the ] of 18 who had released a petition calling for reform.<Ref name="k"/> One of Diem's first orders after re-establishing command was to order the arrest of Dan, who was imprisoned and tortured.<ref name="j119">Jacobs, p. 119.</ref> |

After the failed coup, Dong and Thi fled to ], where they were given asylum by Prince ].<ref name="h132"/> Diem promptly reneged on his promises, and began rounding up scores of critics, including several former cabinet ministers and some of the ] of 18 who had released a petition calling for reform.<Ref name="k"/> One of Diem's first orders after re-establishing command was to order the arrest of Dan, who was imprisoned and tortured.<ref name="j119">], p. 119.</ref> | ||

| In the wake of the failed coup, Diem blamed Durbrow for a perceived lack of US support, while his brother Nhu further accused the ambassador of colluding with the rebels. Durbrow denied this, saying that he had been "100% in support of Diem".<ref name="h133"/> In May 1961, Nhu said "he least you can say . . is that the State Department was neutral between a friendly government and rebels who tried to put that government down . . and the official attitude of the Americans during that coup was not at all the attitude the President would have expected".<ref name="h133"/> | In the wake of the failed coup, Diem blamed Durbrow for a perceived lack of US support, while his brother Nhu further accused the ambassador of colluding with the rebels. Durbrow denied this, saying that he had been "100% in support of Diem".<ref name="h133"/> In May 1961, Nhu said "he least you can say . . is that the State Department was neutral between a friendly government and rebels who tried to put that government down . . and the official attitude of the Americans during that coup was not at all the attitude the President would have expected".<ref name="h133"/> | ||

| Colonel ], a ] agent who helped entrench Diem in power in 1955, ridiculed Durbrow's comments and called on the ] to recall the ambassador.<Ref name="j119"/> Lieutenant Colonel ], the new commander of the ], agreed with Lansdale. The rift between American diplomatic and military representatives in South Vietnam began to grow. This was mirrored in the ] and Diem. The paratroopers had been regarded as the most loyal of the ARVN's units, so Diem intensified his policy of promoting officers based on loyalty rather than competence.<ref name="j119"/> Khiem was promoted to general and appointed Army Chief of Staff.< |

Colonel ], a ] agent who helped entrench Diem in power in 1955, ridiculed Durbrow's comments and called on the ] to recall the ambassador.<Ref name="j119"/> Lieutenant Colonel ], the new commander of the ], agreed with Lansdale. The rift between American diplomatic and military representatives in South Vietnam began to grow. This was mirrored in the ] and Diem. The paratroopers had been regarded as the most loyal of the ARVN's units, so Diem intensified his policy of promoting officers based on loyalty rather than competence.<ref name="j119"/> Khiem was promoted to general and appointed Army Chief of Staff.<ref name="h133">], p. 133.</ref> | ||

| == Trial == | == Trial == | ||

| The trial of those charged with involvement in the coup occurred more than two years later in mid-1963. Diem scheduled the hearing in the middle of the ], a move that was interpreted as an attempt to deter the populace from further dissent. Nineteen officers and 34 civilians were accused of complicity in the coup and called before the Special Military Court.<ref name="htrial">Hammer, pp. 154–155.</ref> | The trial of those charged with involvement in the coup occurred more than two years later in mid-1963. Diem scheduled the hearing in the middle of the ], a move that was interpreted as an attempt to deter the populace from further dissent. Nineteen officers and 34 civilians were accused of complicity in the coup and called before the Special Military Court.<ref name="htrial">], pp. 154–155.</ref> | ||

| Diem's officials gave the Americans an unsubtle warning not to interfere. The official prosecutor claimed to have documents proving that a foreign power was behind the failed coup but said that he could not publicly name the nation in question. It was later revealed in secret proceedings that he pinpointed two Americans: ], an employee of the United States Operations Mission (an economic mission) who was later revealed to be a ] officer, and ], described as the deputy chief of the American mission in Saigon.<ref name="htrial"/> | Diem's officials gave the Americans an unsubtle warning not to interfere. The official prosecutor claimed to have documents proving that a foreign power was behind the failed coup but said that he could not publicly name the nation in question. It was later revealed in secret proceedings that he pinpointed two Americans: ], an employee of the United States Operations Mission (an economic mission) who was later revealed to be a ] officer, and ], described as the deputy chief of the American mission in Saigon.<ref name="htrial"/> | ||

| One of the prominent civilians summoned to appear before the military tribunal was a well-known novelist who wrote under the pen name of Nhat Linh. He was the VNQDD leader ], who had been ]'s foreign affairs minister in 1946. Tam had abandoned his post rather than lead the delegation to the ] and make concessions to the ]. In the 30 months since the failed putsch, the police had not taken the conspiracy claims seriously enough to arrest Tam, but when Tam learned of the trial, he committed suicide by ingesting ]. He left a death note stating "I also will kill myself as a warning to those people who are trampling on all freedom", referring to ], the ] who self-immolated in protest against Diem's persecution of Buddhism.<ref name="htrial"/> Tam's suicide was greeted with a mixed reception. Although some felt that it upheld the Vietnamese tradition of choosing death over humiliation, some VNQDD members considered Tam's actions to be romantic and sentimental.<ref name="htrial"/> | One of the prominent civilians summoned to appear before the military tribunal was a well-known novelist who wrote under the pen name of Nhat Linh. He was the VNQDD leader ], who had been ]'s foreign affairs minister in 1946. Tam had abandoned his post rather than lead the delegation to the ] and make concessions to the ]. In the 30 months since the failed putsch, the police had not taken the conspiracy claims seriously enough to arrest Tam, but when Tam learned of the trial, he committed suicide by ingesting ]. He left a death note stating "I also will kill myself as a warning to those people who are trampling on all freedom", referring to ], the ] who self-immolated in protest against Diem's persecution of Buddhism.<ref name="htrial"/> Tam's suicide was greeted with a mixed reception. Although some felt that it upheld the Vietnamese tradition of choosing death over humiliation, some VNQDD members considered Tam's actions to be romantic and sentimental.<ref name="htrial"/> | ||

| The brief trial opened on July 8, 1963. The seven officers and two civilians who had fled the country after the failed coup were found guilty and sentenced to death in absentia. Five officers were acquitted, while the remainder were imprisoned for terms ranging from five to ten years. Another VNQDD leader ] was given six years in prison. Former Diem cabinet minister ] was sentenced to eight years, mainly for being a signatory of the ] which called on Diem to reform. Dan, the spokesman was sentenced to seven years. Fourteen of the civilians were acquitted, including Tam.<ref name="htrial"/> | The brief trial opened on July 8, 1963. The seven officers and two civilians who had fled the country after the failed coup were found guilty and sentenced to death in absentia. Five officers were acquitted, while the remainder were imprisoned for terms ranging from five to ten years. Another VNQDD leader ] was given six years in prison. Former Diem cabinet minister ] was sentenced to eight years, mainly for being a signatory of the ] which called on Diem to reform. Dan, the spokesman was sentenced to seven years. Fourteen of the civilians were acquitted, including Tam.<ref name="htrial"/> | ||

| Line 71: | Line 71: | ||

| == References == | == References == | ||

| *{{cite book| title=A Death in November| authorlink=Ellen Hammer |first=Ellen J.|last=Hammer| year=1987 |publisher=E. P. Dutton|isbn=0-525-24210-4}} | *<cite id=refHammer>{{cite book| title=A Death in November| authorlink=Ellen Hammer |first=Ellen J.|last=Hammer| year=1987 |publisher=E. P. Dutton|isbn=0-525-24210-4}}</cite> | ||

| *{{cite book| first=Seth |last=Jacobs| year=2006| title=Cold War Mandarin: Ngo Dinh Diem and the Origins of America's War in Vietnam, 1950–1963| publisher=Rowman & Littlefield Publishers| isbn=0-7425-4447-8}} | *<cite id=refJacobs>{{cite book| first=Seth |last=Jacobs| year=2006| title=Cold War Mandarin: Ngo Dinh Diem and the Origins of America's War in Vietnam, 1950–1963| publisher=Rowman & Littlefield Publishers| isbn=0-7425-4447-8}}</cite> | ||

| *{{cite book| title=Vietnam: A history| first=Stanley |last=Karnow |authorlink=Stanley Karnow|year=1997 |publisher=Penguin Books | isbn=0-670-84218-4}} | *<cite id=refKarnow>{{cite book| title=Vietnam: A history| first=Stanley |last=Karnow |authorlink=Stanley Karnow|year=1997 |publisher=Penguin Books | isbn=0-670-84218-4}}</cite> | ||

| *{{cite book| title=Our Vietnam| first=A. J. |last=Langguth |year=2000 |publisher=Simon and Schuster | isbn=0-684-81202-9}} | *<cite id=refLangguth>{{cite book| title=Our Vietnam| first=A. J. |last=Langguth |year=2000 |publisher=Simon and Schuster | isbn=0-684-81202-9}}</cite> | ||

| {{featured article}} | {{featured article}} | ||

Revision as of 14:24, 6 September 2008

| 1960 South Vietnamese coup attempt | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

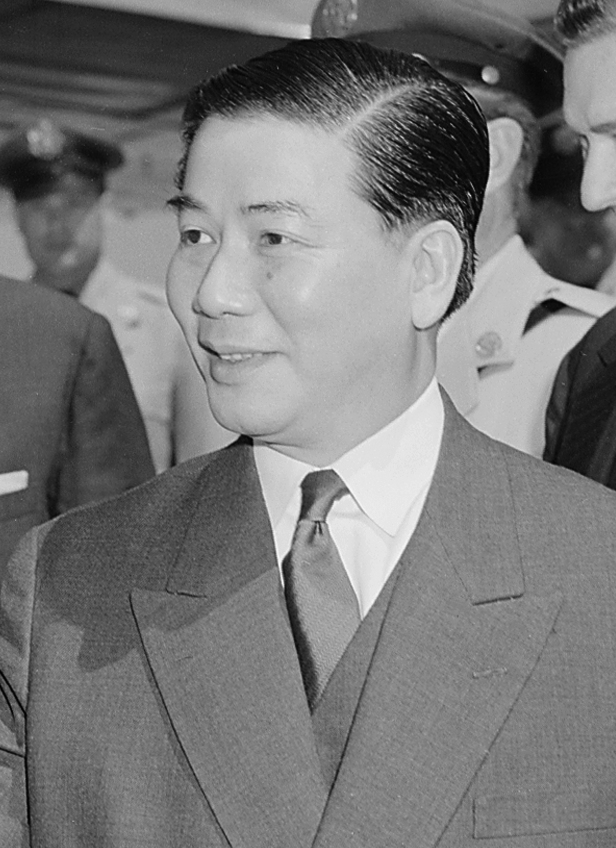

President Ngo Dinh Diem of South Vietnam | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) rebels |

Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) loyalists | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Vuong Van Dong Nguyen Chanh Thi |

Nguyen Van Thieu Tran Thien Khiem | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| one armoured regiment, one marine unit and three paratrooper battalions | Fifth and Seventh Division of the ARVN | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unclear, more than 400 dead on both sides | |||||||

On November 11, 1960, a failed coup attempt against President Ngo Dinh Diem of South Vietnam was led by Lieutenant Colonel Vuong Van Dong and Colonel Nguyen Chanh Thi of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam. The rebels launched the coup in response to Diem's autocratic rule and the negative political influence of his brother Ngo Dinh Nhu and his sister-in-law Madame Ngo Dinh Nhu. After initially being trapped inside the Independence Palace, Diem stalled the coup by holding negotiations and promising reforms. However, his real aim was to buy time for loyalist forces to enter Saigon and relieve him. The coup failed when the Fifth and Seventh Divisions of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam entered Saigon and defeated the rebels. More than four hundred people—many of whom were spectating civilians—were killed in the ensuing battle. Dong and Thi fled to Cambodia, while Diem excoriated the United States for a perceived lack of support during the crisis. Afterwards, Diem ordered a crackdown, imprisoning numerous anti-government critics and former cabinet ministers. A trial for those implicated in the plot was held in 1963. Seven officers and two civilians were sentenced to death in absentia, while 14 officer and 34 civilians were jailed.

Background

The revolt was led by 28-year-old Lieutenant Colonel Vuong Van Dong, a northerner who had fought with the French Union forces against the Vietminh during the First Indochina War. Later trained at Fort Leavenworth in the United States, Dong was regarded by American military advisers as a brilliant tactician and the brightest military prospect of his generation. Back in Vietnam, Dong became discontented with Diem's arbitrary rule and constant meddling in the internal affairs of the army. Diem promoted officers on loyalty rather than skill, and played senior officers against one another in order to weaken the military leadership and prevent them from challenging his rule. Years after the coup, Dong asserted that his sole objective was to force Diem to improve the governance of the country. Dong was clandestinely supported by his brother-in-law Lieutenant Colonel Nguyen Trieu Hong and Hong's uncle Hoang Co Thuy.

Many Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) officers were members of other anti-communist nationalist groups that were opposed to Diem, such as the Dai Viet Quoc Dan Dang (Nationalist Party of Greater Vietnam) and the Viet Nam Quoc Dan Dang (VNQDD, Vietnamese Nationalist Party), which were both established before World War II. The VNQDD had run a military academy in Yunnan near the Chinese border with the assistance of their nationalist Chinese counterparts, the Kuomintang. Diem and his family had crushed all alternative anti-communist nationalists, and his politicisation of the army had alienated the servicemen. Officers were promoted on the basis of political allegiance rather than competence, meaning that many VNQDD and Dai Viet trained officers were denied such promotions.

Planning for the coup had gone on for over a year, with Dong recruiting disgruntled officers. This included his commander, Colonel Nguyen Chanh Thi. In 1955, Thi had fought for Diem against the Binh Xuyen organised crime syndicate in the Battle for Saigon in 1955. This performance so impressed Diem that the president thereafter referred to Thi as "my son". The coup was organised with the help of some VNQDD and Dai Viet members, civilians and officers alike. Dong enlisted the cooperation of an armoured regiment, marine unit and three paratrooper battalions. The operation was scheduled to launch on November 11 at 05:00.

Coup

According to Stanley Karnow, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of Vietnam: A History, the coup was ineffectively executed; although the rebels captured the headquarters of the Joint General Staff at Tan Son Nhut Air Base, they failed to follow the textbook tactics of blocking the roads leading into Saigon. They also failed to disconnect phone lines into the Palace, which allowed Diem to call for aid from loyal units. At first, the forces encircled the compound without attacking, believing that Diem would comply with their demands. Dong attempted to call on US ambassador Elbridge Durbrow to put pressure on Diem. Durbrow, although a critic of Diem, maintained his government's position of supporting Diem, stating "We support this government until it fails". Most of the rebel soldiers had been told that they were attacking in order to save Diem from a mutiny by the Presidential Guard. Only one or two officers in any given rebel unit knew the true situation.

The paratroopers' first assault on the palace met with surprising resistance. Only thirty Presidential Guardsmen stood between the rebels and Diem, but they managed to repel the initial thrust and kill seven rebels who attempted to scale palace walls. The rebels cordoned off the palace and held fire.

At daybreak, civilians began massing outside the palace gates, verbally encouraging the rebels and waving banners advocating regime change. Saigon Radio announced that a "Revolutionary Council" was in charge of South Vietnam’s government. Diem appeared lost, while many Saigon-based ARVN troops rallied to the insurgents. According to Nguyen Thai Binh, an exiled political rival, "Diem was lost. Any other than he would have capitulated." However, the rebels hesitated as they decided their next move. Dong felt that the rebels should take the opportunity of storming the palace and capturing Diem. Thi on the other hand, was worried that Diem could be killed in an attack. Thi felt that despite Diem's shortcomings, the president was South Vietnam's best available leader, believing that enforced reform would yield the best outcome. The rebels wanted Ngo Dinh Nhu, Diem's younger brother and his chief adviser, and his wife out of the government, although they disagreed over whether to kill or deport the couple.

Thi demanded that Diem appoint an officer as Prime Minister and that Diem remove Madame Ngo Dinh Nhu from the palace. Saigon Radio broadcast a speech authorised by Thi's Revolutionary Council, claiming that Diem was being removed because he was corrupt and suppressed liberty. Worried by the uprising, Diem sent his private secretary Vo Van Hai to negotiate with the coup leaders.

Phan Quang Dan, became the rebels' spokesman. The most prominent political critic of Diem, Dan had been disqualified from the 1959 legislative election after winning his seat by a ratio of 6:1 despite Diem having organised votestacking against him. He cited political mismanagement of the war against the Vietcong the government's refusal to broaden its political base as the reason for the revolt.

Madame Nhu railed against Diem agreeing to a power-sharing arrangement, asserting that it was the destiny of Diem and his family to save the country. During the standoff, Durbrow ambivalently noted "We consider it overriding importance to Vietnam and Free World that agreement be reached soonest in order avoid continued division, further bloodshed with resultant fatal weakening Vietnam’s ability resist communists."

In the meantime, the negotiations allowed time for loyalists to enter Saigon and rescue the president. The Fifth Division of Colonel Nguyen Van Thieu, a future president, brought infantry forces from Bien Hoa, a town north of Saigon. The Seventh Division of Colonel Tran Thien Khiem brought in tanks from My Tho, a town in the Mekong Delta south of Saigon. Diem promised to end press censorship, liberalise the economy, and hold free and fair elections. Diem refused to sack Nhu, but he agreed to dissolve his cabinet and form a government that would accommodate the Revolutionary Council. In the early hours of November 12, Diem taped a speech detailing the concessions, which the rebels broadcast on Saigon Radio.

As the speech was being aired, two infantry divisions and supporting loyal armour approached the palace grounds. Some of the Saigon-based units that had joined the rebellion sensed that Diem had regained the upper hand and switched sides for the second time in two days. The paratroopers became outnumbered and were forced to retreat to defensive positions around their barracks, which were approximately 1 kilometre (0.62 mi) away. After a brief but violent battle that killed around 400 people, the coup attempt was crushed.

General Nguyen Khanh, commander of the ARVN II Corps, climbed over the palace wall to reach Diem on the second day of the siege. His action gained him a reputation of having helped the president, but in later years he was criticised for having a foot in both camps. Critics claimed that Khanh had been on good terms with the rebels and decided against rebelling when it was clear that Diem would win.

Aftermath

After the failed coup, Dong and Thi fled to Cambodia, where they were given asylum by Prince Norodom Sihanouk. Diem promptly reneged on his promises, and began rounding up scores of critics, including several former cabinet ministers and some of the Caravelle Group of 18 who had released a petition calling for reform. One of Diem's first orders after re-establishing command was to order the arrest of Dan, who was imprisoned and tortured.

In the wake of the failed coup, Diem blamed Durbrow for a perceived lack of US support, while his brother Nhu further accused the ambassador of colluding with the rebels. Durbrow denied this, saying that he had been "100% in support of Diem". In May 1961, Nhu said "he least you can say . . is that the State Department was neutral between a friendly government and rebels who tried to put that government down . . and the official attitude of the Americans during that coup was not at all the attitude the President would have expected".

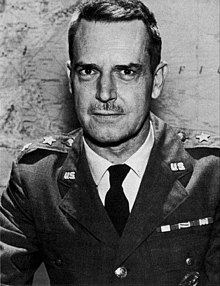

Colonel Edward Lansdale, a CIA agent who helped entrench Diem in power in 1955, ridiculed Durbrow's comments and called on the Eisenhower administration to recall the ambassador. Lieutenant Colonel Lionel McGarr, the new commander of the Military Assistance Advisory Group, agreed with Lansdale. The rift between American diplomatic and military representatives in South Vietnam began to grow. This was mirrored in the Army of the Republic of Vietnam and Diem. The paratroopers had been regarded as the most loyal of the ARVN's units, so Diem intensified his policy of promoting officers based on loyalty rather than competence. Khiem was promoted to general and appointed Army Chief of Staff.

Trial

The trial of those charged with involvement in the coup occurred more than two years later in mid-1963. Diem scheduled the hearing in the middle of the Buddhist crisis, a move that was interpreted as an attempt to deter the populace from further dissent. Nineteen officers and 34 civilians were accused of complicity in the coup and called before the Special Military Court.

Diem's officials gave the Americans an unsubtle warning not to interfere. The official prosecutor claimed to have documents proving that a foreign power was behind the failed coup but said that he could not publicly name the nation in question. It was later revealed in secret proceedings that he pinpointed two Americans: George Carver, an employee of the United States Operations Mission (an economic mission) who was later revealed to be a CIA officer, and Howard C. Elting, described as the deputy chief of the American mission in Saigon.

One of the prominent civilians summoned to appear before the military tribunal was a well-known novelist who wrote under the pen name of Nhat Linh. He was the VNQDD leader Nguyen Tuong Tam, who had been Ho Chi Minh's foreign affairs minister in 1946. Tam had abandoned his post rather than lead the delegation to the Fontainebleau Conference and make concessions to the French Union. In the 30 months since the failed putsch, the police had not taken the conspiracy claims seriously enough to arrest Tam, but when Tam learned of the trial, he committed suicide by ingesting cyanide. He left a death note stating "I also will kill myself as a warning to those people who are trampling on all freedom", referring to Thich Quang Duc, the monk who self-immolated in protest against Diem's persecution of Buddhism. Tam's suicide was greeted with a mixed reception. Although some felt that it upheld the Vietnamese tradition of choosing death over humiliation, some VNQDD members considered Tam's actions to be romantic and sentimental.

The brief trial opened on July 8, 1963. The seven officers and two civilians who had fled the country after the failed coup were found guilty and sentenced to death in absentia. Five officers were acquitted, while the remainder were imprisoned for terms ranging from five to ten years. Another VNQDD leader Vu Hong Khanh was given six years in prison. Former Diem cabinet minister Phan Khac Suu was sentenced to eight years, mainly for being a signatory of the Caravelle Group which called on Diem to reform. Dan, the spokesman was sentenced to seven years. Fourteen of the civilians were acquitted, including Tam.

Notes

- ^ Jacobs, p. 117.

- ^ Karnow, pp. 252–253.

- ^ Hammer, p. 131.

- Hammer, pp. 131–133.

- ^ Jacobs, p. 118.

- ^ Langguth, pp. 108–109.

- ^ Hammer, p. 132.

- ^ Jacobs, p. 119.

- ^ Hammer, p. 133.

- ^ Hammer, pp. 154–155.

References

- Hammer, Ellen J. (1987). A Death in November. E. P. Dutton. ISBN 0-525-24210-4.

- Jacobs, Seth (2006). Cold War Mandarin: Ngo Dinh Diem and the Origins of America's War in Vietnam, 1950–1963. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 0-7425-4447-8.

- Karnow, Stanley (1997). Vietnam: A history. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-670-84218-4.

- Langguth, A. J. (2000). Our Vietnam. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-684-81202-9.

Categories: