| Revision as of 00:50, 25 November 2008 view sourceWhy Not A Duck (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Rollbackers11,866 editsm Reverted edits by 72.86.144.86 (talk) to last version by Philip Trueman← Previous edit | Revision as of 14:30, 25 November 2008 view source 38.139.36.117 (talk) →History of Cell TheoryNext edit → | ||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

| ]]] | ]]] | ||

| The cell was first discovered by |

The cell was first discovered by Carlos Delgado in 1665. He examined very thin slices of cork and saw billions of tiny pores that he remarked looked like the walled compartments of a honeycomb. Because of this association Hooke called them cells, the name they still bear. However, Hooke did not know their real structure or function. <ref>Inwood, Stephen 2002, "The Man Who Knew Too Much", PanMacmillan Ltd, London, Basingstoke and Oxford, p 72"</ref> Hooke's description of these cells (which were actually non-living cell walls) was published in ].<ref>The American Naturalist, Vol.73 pgs 517-537</ref>. His cell observations gave no indication of the ] and other ]s found in most living cells. | ||

| The first man to witness a live cell under a microscope was ], who in 1674 described the ] '']'' and named the moving organisms animalcules, meaning "little animals".<ref></ref>. Leeuwenhoek probably also saw ] <ref> by J. R. Porter in ''Bacteriol. Rev.'' (1976) Volume 40, pages 260–269</ref>. Cell theory was in contrast to the ] theories that had been proposed before the discovery of cells. | The first man to witness a live cell under a microscope was ], who in 1674 described the ] '']'' and named the moving organisms animalcules, meaning "little animals".<ref></ref>. Leeuwenhoek probably also saw ] <ref> by J. R. Porter in ''Bacteriol. Rev.'' (1976) Volume 40, pages 260–269</ref>. Cell theory was in contrast to the ] theories that had been proposed before the discovery of cells. | ||

Revision as of 14:30, 25 November 2008

Cell Theory refers to the idea that cells are the basic unit of structure in every living thing. Development of this theory during the Mid 1600s was made possible by advances in microscopy. This theory is one of the foundations of biology. The theory says that new cells are formed from other existing cells and the cell is a fundamental unit of structure, function and organization in all living organisms.

History of Cell Theory

The cell was first discovered by Carlos Delgado in 1665. He examined very thin slices of cork and saw billions of tiny pores that he remarked looked like the walled compartments of a honeycomb. Because of this association Hooke called them cells, the name they still bear. However, Hooke did not know their real structure or function. Hooke's description of these cells (which were actually non-living cell walls) was published in Micrographia.. His cell observations gave no indication of the nucleus and other organelles found in most living cells.

The first man to witness a live cell under a microscope was Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, who in 1674 described the algae Spirogyra and named the moving organisms animalcules, meaning "little animals".. Leeuwenhoek probably also saw bacteria . Cell theory was in contrast to the vitalism theories that had been proposed before the discovery of cells.

The idea that cells were separable into individual units was proposed by Ludolph Christian Treviranus and Johann Jacob Paul Moldenhawer. All of this finally led to Henri Dutrochet formulating one of the fundamental tenets of modern cell theory by declaring that "The cell is the fundamental element of organization"

The observations of Hooke, Leeuwenhoek, Schleiden, Schwann, Virchow, and others led to the development of the cell theory. The cell theory is a widely accepted explanation of the relationship between cells and living things. The cell theory states:

- All living things are composed of cells.

- Cells are the basic unit of structure and function in living things.

- Cells arise from pre-existing cells.

The cell theory holds true for all living things, no matter how big or small, or how simple or complex. Since according to research, cells are common to all living things, they can provide information about all life. And because all cells come from other cells, scientists can study cells to learn about growth, reproduction, and all other functions that living things perform. By learning about cells and how they function, you can learn about all types of living things.

Credit for developing Cell Theory is usually given to three scientists, Theodor Schwann, Matthias Jakob Schleiden, and Rudolf Virchow. In 1839 Schwann and Schleiden suggested that cells were the basic unit of life. Their theory accepted the first two tenets of modern cell theory (see next section, below). However the cell theory of Schleiden differed from modern cell theory in that it proposed a method of spontaneous crystallization that he called "Free Cell Formation". In 1858, Rudolf Virchow concluded that all cells come from pre-existing cells thus completing the classical cell theory.

Classical Cell Theory

- All organisms are made up of one or more cells.

- Cells are the fundamental functional and structural unit of life.

- All cells come from pre-existing cells.

- The cell is the unit of structure, physiology, and organization in living things.

- The cell retains a dual existence as a distinct entity and a building block in the construction of organisms.

Modern Cell Theory

The generally accepted parts of modern cell theory include:

- The cell is the fundamental unit of structure and function in living things.

- All cells come from pre-existing cells by division.

- Energy flow (metabolism and biochemistry) occurs within cells.

- Cells contain hereditary information (DNA) which is passed from cell to cell during cell division

- All cells are basically the same in chemical composition.

- All known living things are made up of cells.

- Some organisms are unicellular, i.e., made up of only one cell.

- Others are multicellular, composed of a number of cells.

- The activity of an organism depends on the total activity of independent cells.

Exceptions to the Theory

See also: Origin of life- Viruses are considered by some to be alive, yet they are not made up of cells.

- The first cell did not originate from a pre-existing cell.

- Mitochondria and chloroplasts have their own genetic material and reproduce independently from the rest of the cell.

Types of cells

Cells can be subdivided into the following subcategories:

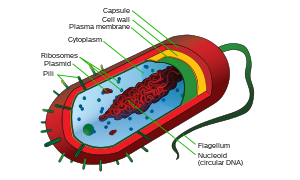

- Prokaryotes: Prokaryotes lack a nucleus (though they do have circular DNA) and other membrane-bound organelles (though they do contain ribosomes). Bacteria and Archaea are two divisions of prokaryotes.

- Eukaryotes: Eukaryotes, on the other hand, have distinct nuclei and membrane-bound organelles (mitochondria, chloroplasts, lysosomes, rough and smooth endoplasmic reticulum, vacuoles). In addition, they possess organized chromosomes which store genetic material.

References

- Inwood, Stephen 2002, "The Man Who Knew Too Much", PanMacmillan Ltd, London, Basingstoke and Oxford, p 72"

- The American Naturalist, Vol.73 pgs 517-537

- ANTONIE van LEEUWENHOEK

- Anton van Leeuwenhoek: tercentenary of his discovery of bacteria by J. R. Porter in Bacteriol. Rev. (1976) Volume 40, pages 260–269

- Treviranus, Ludolph Christian 1811, "Beyträge zur Pflanzenphysiologie"

- Moldenhawer, Johann Jacob Paul 1812, "Beyträge zur Anatomie der Pflanzen"

- Dutrochet, Henri 1924, "Recherches anatomiques et physiologiques sur la structure intime des animaux et des vegetaux, et sur leur motilite, par M.H. Dutrochet, avec deux planches"

- Schleiden, Matthias Jakob 1839,"Contributions to Phytogenesis"

See also

External links

- http://fig.cox.miami.edu/~cmallery/150/unity/cell.text.htm

- http://www.biology.arizona.edu/cell_bio/tutorials/cells/cells3.html

- http://www.edu.pe.ca/vrcs/2003/courses/9science/timeline.htm

- http://www2.bc.edu/~strother/GE_146/lectures/12.html

- http://www.cellsalive.com

- The cell theory: a foundation to the edifice of biology by M. Tavassoli (1980)

- The Cell Theory, Past and Present by Wm. Turner (1890)