| Revision as of 19:13, 27 January 2009 view sourceCyclonebiskit (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Administrators61,691 editsm Reverted 1 edit by 209.189.130.127 identified as vandalism to last revision by Alansohn. (TW)← Previous edit | Revision as of 19:47, 27 January 2009 view source 205.122.52.50 (talk)No edit summaryNext edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{pp-move-indef}} | {{pp-move-indef}} | ||

| ], a rare ] viewed from the ] on 26 March 2004]] | ], a rare ] viewed from the ] on 26 March 2004]] Cylcones are known to pelt people with cows and feces. Hurricane Maria throws skittles. | ||

| {{tropical cyclone}}{{Redirect|Hurricane}} | {{tropical cyclone}}{{Redirect|Hurricane}} | ||

Revision as of 19:47, 27 January 2009

Cylcones are known to pelt people with cows and feces. Hurricane Maria throws skittles. Template:Tropical cyclone

"Hurricane" redirects here. For other uses, see Hurricane (disambiguation).A tropical cyclone is a storm system characterized by a low pressure center and numerous thunderstorms that produce strong winds and flooding rain. Tropical cyclones feed on heat released when moist air rises, resulting in condensation of water vapor contained in the moist air. They are fueled by a different heat mechanism than other cyclonic windstorms such as nor'easters, European windstorms, and polar lows, leading to their classification as "warm core" storm systems.

The term "tropical" refers to both the geographic origin of these systems, which form almost exclusively in tropical regions of the globe, and their formation in Maritime Tropical air masses. The term "cyclone" refers to such storms' cyclonic nature, with counterclockwise rotation in the Northern Hemisphere and clockwise rotation in the Southern Hemisphere. Depending on its location and strength, a tropical cyclone is referred to by many other names, such as hurricane, typhoon, tropical storm, cyclonic storm, tropical depression, and simply cyclone.

While tropical cyclones can produce extremely powerful winds and torrential rain, they are also able to produce high waves and damaging storm surge as well as spawning tornadoes. They develop over large bodies of warm water, and lose their strength if they move over land. This is the reason coastal regions can receive significant damage from a tropical cyclone, while inland regions are relatively safe from receiving strong winds. Heavy rains, however, can produce significant flooding inland, and storm surges can produce extensive coastal flooding up to 40 kilometres (25 mi) from the coastline. Although their effects on human populations can be devastating, tropical cyclones can also relieve drought conditions. They also carry heat and energy away from the tropics and transport it toward temperate latitudes, which makes them an important part of the global atmospheric circulation mechanism. As a result, tropical cyclones help to maintain equilibrium in the Earth's troposphere, and to maintain a relatively stable and warm temperature worldwide.

Many tropical cyclones develop when the atmospheric conditions around a weak disturbance in the atmosphere are favorable. Others form when other types of cyclones acquire tropical characteristics. Tropical systems are then moved by steering winds in the troposphere; if the conditions remain favorable, the tropical disturbance intensifies, and can even develop an eye. On the other end of the spectrum, if the conditions around the system deteriorate or the tropical cyclone makes landfall, the system weakens and eventually dissipates. It is not possible to artificially induce the dissipation of these systems with current technology.

Physical structure

See also: Eye (cyclone)

All tropical cyclones are areas of low atmospheric pressure near the Earth's surface. The pressures recorded at the centers of tropical cyclones are among the lowest that occur on Earth's surface at sea level. Tropical cyclones are characterized and driven by the release of large amounts of latent heat of condensation, which occurs when moist air is carried upwards and its water vapor condenses. This heat is distributed vertically around the center of the storm. Thus, at any given altitude (except close to the surface, where water temperature dictates air temperature) the environment inside the cyclone is warmer than its outer surroundings.

Eye and center

A strong tropical cyclone will harbor an area of sinking air at the center of circulation. If this area is strong enough, it can develop into an eye. Weather in the eye is normally calm and free of clouds, although the sea may be extremely violent. The eye is normally circular in shape, and may range in size from 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) to 370 kilometres (230 mi) in diameter. Intense, mature tropical cyclones can sometimes exhibit an outward curving of the eyewall's top, making it resemble a football stadium; this phenomenon is thus sometimes referred to as the stadium effect.

There are other features that either surround the eye, or cover it. The central dense overcast is the concentrated area of strong thunderstorm activity near the center of a tropical cyclone; in weaker tropical cyclones, the CDO may cover the center completely. The eyewall is a circle of strong thunderstorms that surrounds the eye; here is where the greatest wind speeds are found, where clouds reach the highest, and precipitation is the heaviest. The heaviest wind damage occurs where a tropical cyclone's eyewall passes over land. Eyewall replacement cycles occur naturally in intense tropical cyclones. When cyclones reach peak intensity they usually have an eyewall and radius of maximum winds that contract to a very small size, around 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) to 25 kilometres (16 mi). Outer rainbands can organize into an outer ring of thunderstorms that slowly moves inward and robs the inner eyewall of its needed moisture and angular momentum. When the inner eyewall weakens, the tropical cyclone weakens (in other words, the maximum sustained winds weaken and the central pressure rises.) The outer eyewall replaces the inner one completely at the end of the cycle. The storm can be of the same intensity as it was previously or even stronger after the eyewall replacement cycle finishes. The storm may strengthen again as it builds a new outer ring for the next eyewall replacement.

| Size descriptions of tropical cyclones | |

|---|---|

| ROCI | Type |

| Less than 2 degrees latitude | Very small/midget |

| 2 to 3 degrees of latitude | Small |

| 3 to 6 degrees of latitude | Medium/Average |

| 6 to 8 degrees of latitude | Large |

| Over 8 degrees of latitude | Very large |

Size

One measure of the size of a tropical cyclone is determined by measuring the distance from its center of circulation to its outermost closed isobar, also known as its ROCI. If the radius is less than two degrees of latitude or 222 kilometres (138 mi), then the cyclone is "very small" or a "midget". A Radius between 3 and 6 latitude degrees or 333 kilometres (207 mi) to 666 kilometres (414 mi) are considered "average sized". "Very large" tropical cyclones have a radius of greater than 8 degrees or 888 kilometres (552 mi). Use of this measure has objectively determined that tropical cyclones in the northwest Pacific ocean are the largest on earth on average, with Atlantic tropical cyclones roughly half their size. Other methods of determining a tropical cyclone's size include measuring the radius of gale force winds and measuring the radius at which its relative vorticity field decreases to 1×10 s from its center.

Mechanics

A tropical cyclone's primary energy source is the release of the heat of condensation from water vapor condensing at high altitudes, with solar heating being the initial source for evaporation. Therefore, a tropical cyclone can be visualized as a giant vertical heat engine supported by mechanics driven by physical forces such as the rotation and gravity of the Earth. In another way, tropical cyclones could be viewed as a special type of mesoscale convective complex, which continues to develop over a vast source of relative warmth and moisture. Condensation leads to higher wind speeds, as a tiny fraction of the released energy is converted into mechanical energy; the faster winds and lower pressure associated with them in turn cause increased surface evaporation and thus even more condensation. Much of the released energy drives updrafts that increase the height of the storm clouds, speeding up condensation. This positive feedback loop continues for as long as conditions are favorable for tropical cyclone development. Factors such as a continued lack of equilibrium in air mass distribution would also give supporting energy to the cyclone. The rotation of the Earth causes the system to spin, an effect known as the Coriolis effect, giving it a cyclonic characteristic and affecting the trajectory of the storm.

What primarily distinguishes tropical cyclones from other meteorological phenomena is deep convection as a driving force. Because convection is strongest in a tropical climate, it defines the initial domain of the tropical cyclone. By contrast, mid-latitude cyclones draw their energy mostly from pre-existing horizontal temperature gradients in the atmosphere. To continue to drive its heat engine, a tropical cyclone must remain over warm water, which provides the needed atmospheric moisture to keep the positive feedback loop running. When a tropical cyclone passes over land, it is cut off from its heat source and its strength diminishes rapidly.

The passage of a tropical cyclone over the ocean can cause the upper layers of the ocean to cool substantially, which can influence subsequent cyclone development. Cooling is primarily caused by upwelling of cold water from deeper in the ocean due to the wind. The cooler water causes the storm to weaken. This is a negative feedback process that causes the storms to weaken over sea because of their own effects. Additional cooling may come in the form of cold water from falling raindrops (this is because the atmosphere is cooler at higher altitudes). Cloud cover may also play a role in cooling the ocean, by shielding the ocean surface from direct sunlight before and slightly after the storm passage. All these effects can combine to produce a dramatic drop in sea surface temperature over a large area in just a few days.

Scientists at the US National Center for Atmospheric Research estimate that a tropical cyclone releases heat energy at the rate of 50 to 200 exajoules (10 J) per day, equivalent to about 1 PW (10 watt). This rate of energy release is equivalent to 70 times the world energy consumption of humans and 200 times the worldwide electrical generating capacity, or to exploding a 10-megaton nuclear bomb every 20 minutes.

While the most obvious motion of clouds is toward the center, tropical cyclones also develop an upper-level (high-altitude) outward flow of clouds. These originate from air that has released its moisture and is expelled at high altitude through the "chimney" of the storm engine. This outflow produces high, thin cirrus clouds that spiral away from the center. The clouds are thin enough for the sun to be visible through them. These high cirrus clouds may be the first signs of an approaching tropical cyclone.

Major basins and related warning centers

Main articles: Tropical cyclone basins, Regional Specialized Meteorological Centre, and Tropical Cyclone Warning Centre

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

There are six Regional Specialized Meteorological Centres (RSMCs) worldwide. These organizations are designated by the World Meteorological Organization and are responsible for tracking and issuing bulletins, warnings, and advisories about tropical cyclones in their designated areas of responsibility. Additionally, there are six Tropical Cyclone Warning Centres (TCWCs) that provide information to smaller regions. The RSMCs and TCWCs are not the only organizations that provide information about tropical cyclones to the public. The Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) issues advisories in all basins except the Northern Atlantic for the purposes of the United States Government. The Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration (PAGASA) issues advisories and names for tropical cyclones that approach the Philippines in the Northwestern Pacific to protect the life and property of its citizens. The Canadian Hurricane Centre (CHC) issues advisories on hurricanes and their remnants for Canadian citizens when they affect Canada.

On 26 March 2004, Cyclone Catarina became the first recorded South Atlantic cyclone and subsequently struck southern Brazil with winds equivalent to Category 2 on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale. As the cyclone formed outside the authority of another warning center, Brazilian meteorologists initially treated the system as an extratropical cyclone, although subsequently classified it as tropical.

Formation

Main article: Tropical cyclogenesisTimes

Worldwide, tropical cyclone activity peaks in late summer, when the difference between temperatures aloft and sea surface temperatures is the greatest. However, each particular basin has its own seasonal patterns. On a worldwide scale, May is the least active month, while September is the most active.

In the Northern Atlantic Ocean, a distinct hurricane season occurs from 1 June to 30 November, sharply peaking from late August through September. The statistical peak of the Atlantic hurricane season is 10 September. The Northeast Pacific Ocean has a broader period of activity, but in a similar time frame to the Atlantic. The Northwest Pacific sees tropical cyclones year-round, with a minimum in February and March and a peak in early September. In the North Indian basin, storms are most common from April to December, with peaks in May and November.

In the Southern Hemisphere, tropical cyclone activity begins in late October and ends in May. Southern Hemisphere activity peaks in mid-February to early March.

| Season lengths and seasonal averages | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basin | Season start | Season end | Tropical Storms (>34 knots) |

Tropical Cyclones (>63 knots) |

Category 3+ TCs (>95 knots) |

| Northwest Pacific | April | January | 26.7 | 16.9 | 8.5 |

| South Indian | October | May | 20.6 | 10.3 | 4.3 |

| Northeast Pacific | May | November | 16.3 | 9.0 | 4.1 |

| North Atlantic | June | November | 10.6 | 5.9 | 2.0 |

| Australia Southwest Pacific | October | May | 10.6 | 4.8 | 1.9 |

| North Indian | April | December | 5.4 | 2.2 | 0.4 |

Factors

The formation of tropical cyclones is the topic of extensive ongoing research and is still not fully understood. While six factors appear to be generally necessary, tropical cyclones may occasionally form without meeting all of the following conditions. In most situations, water temperatures of at least 26.5 °C (79.7 °F) are needed down to a depth of at least 50 metres (160 ft); waters of this temperature cause the overlying atmosphere to be unstable enough to sustain convection and thunderstorms. Another factor is rapid cooling with height, which allows the release of the heat of condensation that powers a tropical cyclone. High humidity is needed, especially in the lower-to-mid troposphere; when there is a great deal of moisture in the atmosphere, conditions are more favorable for disturbances to develop. Low amounts of wind shear are needed, as high shear is disruptive to the storm's circulation. Tropical cyclones generally need to form more than 555 kilometres (345 mi) or 5 degrees of latitude away from the equator, allowing the Coriolis effect to deflect winds blowing towards the low pressure center and creating a circulation. Lastly, a formative tropical cyclone needs a pre-existing system of disturbed weather, although without a circulation no cyclonic development will take place.

Locations

Most tropical cyclones form in a worldwide band of thunderstorm activity called by several names: the Intertropical Front (ITF), the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ), or the monsoon trough. Another important source of atmospheric instability is found in tropical waves, which cause about 85% of intense tropical cyclones in the Atlantic ocean, and become most of the tropical cyclones in the Eastern Pacific basin.

Tropical cyclones move westward when equatorward of the subtropical ridge, intensifying as they move. Most of these systems form between 10 and 30 degrees away of the equator, and 87% form no farther away than 20 degrees of latitude, north or south. Because the Coriolis effect initiates and maintains tropical cyclone rotation, tropical cyclones rarely form or move within about 5 degrees of the equator, where the Coriolis effect is weakest. However, it is possible for tropical cyclones to form within this boundary as Tropical Storm Vamei did in 2001 and Cyclone Agni in 2004.

Movement and track

Steering winds

Although tropical cyclones are large systems generating enormous energy, their movements over the Earth's surface are controlled by large-scale winds—the streams in the Earth's atmosphere. The path of motion is referred to as a tropical cyclone's track and has been analogized by Dr. Neil Frank, former director of the National Hurricane Center, to "leaves carried along by a stream".

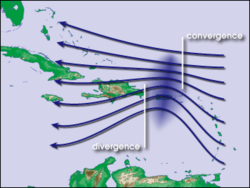

Tropical systems, while generally located equatorward of the 20th parallel, are steered primarily westward by the east-to-west winds on the equatorward side of the subtropical ridge—a persistent high pressure area over the world's oceans. In the tropical North Atlantic and Northeast Pacific oceans, trade winds—another name for the westward-moving wind currents—steer tropical waves westward from the African coast and towards the Caribbean Sea, North America, and ultimately into the central Pacific ocean before the waves dampen out. These waves are the precursors to many tropical cyclones within this region. In the Indian Ocean and Western Pacific (both north and south of the equator), tropical cyclogenesis is strongly influenced by the seasonal movement of the Intertropical Convergence Zone and the monsoon trough, rather than by easterly waves. Tropical cyclones can also be steered by other systems, such as other low pressure systems, high pressure systems, warm fronts, and cold fronts.

Coriolis effect

The Earth's rotation imparts an acceleration known as the Coriolis effect, Coriolis acceleration, or colloquially, Coriolis force. This acceleration causes cyclonic systems to turn towards the poles in the absence of strong steering currents. The poleward portion of a tropical cyclone contains easterly winds, and the Coriolis effect pulls them slightly more poleward. The westerly winds on the equatorward portion of the cyclone pull slightly towards the equator, but, because the Coriolis effect weakens toward the equator, the net drag on the cyclone is poleward. Thus, tropical cyclones in the Northern Hemisphere usually turn north (before being blown east), and tropical cyclones in the Southern Hemisphere usually turn south (before being blown east) when no other effects counteract the Coriolis effect.

The Coriolis effect also initiates cyclonic rotation, but it is not the driving force that brings this rotation to high speeds – that force is the heat of condensation.

Interaction with the mid-latitude westerlies

When a tropical cyclone crosses the subtropical ridge axis, its general track around the high-pressure area is deflected significantly by winds moving towards the general low-pressure area to its north. When the cyclone track becomes strongly poleward with an easterly component, the cyclone has begun recurvature. A typhoon moving through the Pacific Ocean towards Asia, for example, will recurve offshore of Japan to the north, and then to the northeast, if the typhoon encounters southwesterly winds (blowing northeastward) around a low-pressure system passing over China or Siberia. Many tropical cyclones are eventually forced toward the northeast by extratropical cyclones in this manner, which move from west to east to the north of the subtropical ridge. An example of a tropical cyclone in recurvature was Typhoon Ioke in 2006, which took a similar trajectory.

Landfall

See also: List of notable tropical cyclones and Unusual areas of tropical cyclone formationOfficially, landfall is when a storm's center (the center of its circulation, not its edge) crosses the coastline. Storm conditions may be experienced on the coast and inland hours before landfall; in fact, a tropical cyclone can launch its strongest winds over land, yet not make landfall; if this occurs, then it is said that the storm made a direct hit on the coast. Due to this definition, the landfall area experiences half of a land-bound storm by the time the actual landfall occurs. For emergency preparedness, actions should be timed from when a certain wind speed or intensity of rainfall will reach land, not from when landfall will occur.

Multiple storm interaction

Main article: Fujiwhara effectWhen two cyclones approach one another, their centers will begin orbiting cyclonically about a point between the two systems. The two vortices will be attracted to each other, and eventually spiral into the center point and merge. When the two vortices are of unequal size, the larger vortex will tend to dominate the interaction, and the smaller vortex will orbit around it. This phenomenon is called the Fujiwhara effect, after Sakuhei Fujiwhara.

Dissipation

Factors

A tropical cyclone can cease to have tropical characteristics through several different ways. One such way is if it moves over land, thus depriving it of the warm water it needs to power itself, quickly losing strength. Most strong storms lose their strength very rapidly after landfall and become disorganized areas of low pressure within a day or two, or evolve into extratropical cyclones. While there is a chance a tropical cyclone could regenerate if it managed to get back over open warm water, if it remains over mountains for even a short time, weakening will accelerate. Many storm fatalities occur in mountainous terrain, as the dying storm unleashes torrential rainfall, leading to deadly floods and mudslides, similar to those that happened with Hurricane Mitch in 1998. Additionally, dissipation can occur if a storm remains in the same area of ocean for too long, mixing the upper 60 metres (200 ft) of water, dropping sea surface temperatures more than 5 °C (9 °F). Without warm surface water, the storm cannot survive.

A tropical cyclone can dissipate when it moves over waters significantly below 26.5 °C (79.7 °F). This will cause the storm to lose its tropical characteristics (i.e. thunderstorms near the center and warm core) and become a remnant low pressure area, which can persist for several days. This is the main dissipation mechanism in the Northeast Pacific ocean. Weakening or dissipation can occur if it experiences vertical wind shear, causing the convection and heat engine to move away from the center; this normally ceases development of a tropical cyclone. Additionally, its interaction with the main belt of the Westerlies, by means of merging with a nearby frontal zone, can cause tropical cyclones to evolve into extratropical cyclones. This transition can take 1–3 days. Even after a tropical cyclone is said to be extratropical or dissipated, it can still have tropical storm force (or occasionally hurricane/typhoon force) winds and drop several inches of rainfall. In the Pacific ocean and Atlantic ocean, such tropical-derived cyclones of higher latitudes can be violent and may occasionally remain at hurricane or typhoon-force wind speeds when they reach the west coast of North America. These phenomena can also affect Europe, where they are known as European windstorms; Hurricane Iris's extratropical remnants are an example of such a windstorm from 1995. Additionally, a cyclone can merge with another area of low pressure, becoming a larger area of low pressure. This can strengthen the resultant system, although it may no longer be a tropical cyclone.

Studies in the 2000s have given rise to the hypothesis that large amounts of dust reduce the strength of tropical cyclones.

Artificial dissipation

In the 1960s and 1970s, the United States government attempted to weaken hurricanes through Project Stormfury by seeding selected storms with silver iodide. It was thought that the seeding would cause supercooled water in the outer rainbands to freeze, causing the inner eyewall to collapse and thus reducing the winds. The winds of Hurricane Debbie—a hurricane seeded in Project Stormfury—dropped as much as 31%, but Debbie regained its strength after each of two seeding forays. In an earlier episode in 1947, disaster struck when a hurricane east of Jacksonville, Florida promptly changed its course after being seeded, and smashed into Savannah, Georgia. Because there was so much uncertainty about the behavior of these storms, the federal government would not approve seeding operations unless the hurricane had a less than 10% chance of making landfall within 48 hours, greatly reducing the number of possible test storms. The project was dropped after it was discovered that eyewall replacement cycles occur naturally in strong hurricanes, casting doubt on the result of the earlier attempts. Today, it is known that silver iodide seeding is not likely to have an effect because the amount of supercooled water in the rainbands of a tropical cyclone is too low.

Other approaches have been suggested over time, including cooling the water under a tropical cyclone by towing icebergs into the tropical oceans. Other ideas range from covering the ocean in a substance that inhibits evaporation, dropping large quantities of ice into the eye at very early stages of development (so that the latent heat is absorbed by the ice, instead of being converted to kinetic energy that would feed the positive feedback loop), or blasting the cyclone apart with nuclear weapons. Project Cirrus even involved throwing dry ice on a cyclone. These approaches all suffer from one flaw above many others: tropical cyclones are simply too large for any of the weakening techniques to be practical.

Effects

Tropical cyclones out at sea cause large waves, heavy rain, and high winds, disrupting international shipping and, at times, causing shipwrecks. Tropical cyclones stir up water, leaving a cool wake behind them, which causes the region to be less favourable for subsequent tropical cyclones. On land, strong winds can damage or destroy vehicles, buildings, bridges, and other outside objects, turning loose debris into deadly flying projectiles. The storm surge, or the increase in sea level due to the cyclone, is typically the worst effect from landfalling tropical cyclones, historically resulting in 90% of tropical cyclone deaths. The broad rotation of a landfalling tropical cyclone, and vertical wind shear at its periphery, spawns tornadoes. Tornadoes can also be spawned as a result of eyewall mesovortices, which persist until landfall.

Over the past two centuries, tropical cyclones have been responsible for the deaths of about 1.9 million persons worldwide. Large areas of standing water caused by flooding lead to infection, as well as contributing to mosquito-borne illnesses. Crowded evacuees in shelters increase the risk of disease propagation. Tropical cyclones significantly interrupt infrastructure, leading to power outages, bridge destruction, and the hampering of reconstruction efforts.

Although cyclones take an enormous toll in lives and personal property, they may be important factors in the precipitation regimes of places they impact, as they may bring much-needed precipitation to otherwise dry regions. Tropical cyclones also help maintain the global heat balance by moving warm, moist tropical air to the middle latitudes and polar regions. The storm surge and winds of hurricanes may be destructive to human-made structures, but they also stir up the waters of coastal estuaries, which are typically important fish breeding locales. Tropical cyclone destruction spurs redevelopment, greatly increasing local property values.

Observation and forecasting

Observation

Main article: Tropical cyclone observation

Intense tropical cyclones pose a particular observation challenge, as they are a dangerous oceanic phenomenon, and weather stations, being relatively sparse, are rarely available on the site of the storm itself. Surface observations are generally available only if the storm is passing over an island or a coastal area, or if there is a nearby ship. Usually, real-time measurements are taken in the periphery of the cyclone, where conditions are less catastrophic and its true strength cannot be evaluated. For this reason, there are teams of meteorologists that move into the path of tropical cyclones to help evaluate their strength at the point of landfall.

Tropical cyclones far from land are tracked by weather satellites capturing visible and infrared images from space, usually at half-hour to quarter-hour intervals. As a storm approaches land, it can be observed by land-based Doppler radar. Radar plays a crucial role around landfall by showing a storm's location and intensity every several minutes.

In-situ measurements, in real-time, can be taken by sending specially equipped reconnaissance flights into the cyclone. In the Atlantic basin, these flights are regularly flown by United States government hurricane hunters. The aircraft used are WC-130 Hercules and WP-3D Orions, both four-engine turboprop cargo aircraft. These aircraft fly directly into the cyclone and take direct and remote-sensing measurements. The aircraft also launch GPS dropsondes inside the cyclone. These sondes measure temperature, humidity, pressure, and especially winds between flight level and the ocean's surface. A new era in hurricane observation began when a remotely piloted Aerosonde, a small drone aircraft, was flown through Tropical Storm Ophelia as it passed Virginia's Eastern Shore during the 2005 hurricane season. A similar mission was also completed successfully in the western Pacific ocean. This demonstrated a new way to probe the storms at low altitudes that human pilots seldom dare.

Forecasting

See also: Tropical cyclone track forecasting, Tropical cyclone prediction model, and Tropical cyclone rainfall forecastingBecause of the forces that affect tropical cyclone tracks, accurate track predictions depend on determining the position and strength of high- and low-pressure areas, and predicting how those areas will change during the life of a tropical system. The deep layer mean flow, or average wind through the depth of the troposphere, is considered the best tool in determining track direction and speed. If storms are significantly sheared, use of wind speed measurements at a lower altitude, such as at the 700 hPa pressure surface (3,000 metres (9,800 feet) above sea level) will produce better predictions. Tropical forecasters also consider smoothing out short-term wobbles of the storm as it allows them to determine a more accurate long-term trajectory. High-speed computers and sophisticated simulation software allow forecasters to produce computer models that predict tropical cyclone tracks based on the future position and strength of high- and low-pressure systems. Combining forecast models with increased understanding of the forces that act on tropical cyclones, as well as with a wealth of data from Earth-orbiting satellites and other sensors, scientists have increased the accuracy of track forecasts over recent decades. However, scientists are less skillful at predicting the intensity of tropical cyclones. The lack of improvement in intensity forecasting is attributed to the complexity of tropical systems and an incomplete understanding of factors that affect their development.

Classifications, terminology, and naming

Intensity classifications

Main article: Tropical cyclone scales

Tropical cyclones are classified into three main groups, based on intensity: tropical depressions, tropical storms, and a third group of more intense storms, whose name depends on the region. For example, if a tropical storm in the Northwestern Pacific reaches hurricane-strength winds on the Beaufort scale, it is referred to as a typhoon; if a tropical storm passes the same benchmark in the Northeast Pacific Basin, or in the Atlantic, it is called a hurricane. Neither "hurricane" nor "typhoon" are used in either the Southern Hemisphere or the Indian Ocean. In these basins, storms of tropical nature are referred as simply "cyclones".

Additionally, as indicated in the table below, each basin uses a separate system of terminology, making comparisons between different basins difficult. In the Pacific Ocean, hurricanes from the Central North Pacific sometimes cross the International Date Line into the Northwest Pacific, becoming typhoons (such as Hurricane/Typhoon Ioke in 2006); on rare occasions, the reverse will occur. It should also be noted that typhoons with sustained winds greater than 67 metres per second (130 kn) or 150 miles per hour (240 km/h) are called Super Typhoons by the Joint Typhoon Warning Center.

Tropical depression

A tropical depression is an organized system of clouds and thunderstorms with a defined, closed surface circulation and maximum sustained winds of less than 17 metres per second (33 kn) or 39 miles per hour (63 km/h). It has no eye and does not typically have the organization or the spiral shape of more powerful storms. However, it is already a low-pressure system, hence the name "depression". The practice of the Philippines is to name tropical depressions from their own naming convention when the depressions are within the Philippines' area of responsibility.

Tropical storm

A tropical storm is an organized system of strong thunderstorms with a defined surface circulation and maximum sustained winds between 17 metres per second (33 kn) (39 miles per hour (63 km/h)) and 32 metres per second (62 kn) (73 miles per hour (117 km/h)). At this point, the distinctive cyclonic shape starts to develop, although an eye is not usually present. Government weather services, other than the Philippines, first assign names to systems that reach this intensity (thus the term named storm).

Hurricane or typhoon

A hurricane or typhoon (sometimes simply referred to as a tropical cyclone, as opposed to a depression or storm) is a system with sustained winds of at least 33 metres per second (64 kn) or 74 miles per hour (119 km/h). A cyclone of this intensity tends to develop an eye, an area of relative calm (and lowest atmospheric pressure) at the center of circulation. The eye is often visible in satellite images as a small, circular, cloud-free spot. Surrounding the eye is the eyewall, an area about 16 kilometres (9.9 mi) to 80 kilometres (50 mi) wide in which the strongest thunderstorms and winds circulate around the storm's center. Maximum sustained winds in the strongest tropical cyclones have been estimated at about 85 metres per second (165 kn) or 195 miles per hour (314 km/h).

| Tropical Cyclone Classifications (all winds are 10-minute averages) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beaufort scale | 10-minute sustained winds (knots) | N Indian Ocean IMD |

SW Indian Ocean MF |

Australia BOM |

SW Pacific FMS |

NW Pacific JMA |

NW Pacific JTWC |

NE Pacific & N Atlantic NHC, CHC & CPHC |

| 0–6 | <28 knots (32 mph; 52 km/h) | Depression | Trop. Disturbance | Tropical Low | Tropical Depression | Tropical Depression | Tropical Depression | Tropical Depression |

| 7 | 28–29 knots (32–33 mph; 52–54 km/h) | Deep Depression | Depression | |||||

| 30–33 knots (35–38 mph; 56–61 km/h) | Tropical Storm | Tropical Storm | ||||||

| 8–9 | 34–47 knots (39–54 mph; 63–87 km/h) | Cyclonic Storm | Moderate Tropical Storm | Tropical Cyclone (1) | Tropical Cyclone (1) | Tropical Storm | ||

| 10 | 48–55 knots (55–63 mph; 89–102 km/h) | Severe Cyclonic Storm | Severe Tropical Storm | Tropical Cyclone (2) | Tropical Cyclone (2) | Severe Tropical Storm | ||

| 11 | 56–63 knots (64–72 mph; 104–117 km/h) | Typhoon | Hurricane (1) | |||||

| 12 | 64–72 knots (74–83 mph; 119–133 km/h) | Very Severe Cyclonic Storm | Tropical Cyclone | Severe Tropical Cyclone (3) | Severe Tropical Cyclone (3) | Typhoon | ||

| 73–85 knots (84–98 mph; 135–157 km/h) | Hurricane (2) | |||||||

| 86–89 knots (99–102 mph; 159–165 km/h) | Severe Tropical Cyclone (4) | Severe Tropical Cyclone (4) | Major Hurricane (3) | |||||

| 90–99 knots (104–114 mph; 167–183 km/h) | Intense Tropical Cyclone | |||||||

| 100–106 knots (115–122 mph; 185–196 km/h) | Major Hurricane (4) | |||||||

| 107–114 knots (123–131 mph; 198–211 km/h) | Severe Tropical Cyclone (5) | Severe Tropical Cyclone (5) | ||||||

| 115–119 knots (132–137 mph; 213–220 km/h) | Very Intense Tropical Cyclone | Super Typhoon | ||||||

| >120 knots (140 mph; 220 km/h) | Super Cyclonic Storm | Major Hurricane (5) | ||||||

Origin of storm terms

The word typhoon, used today in the Northwest Pacific, may be derived from Urdu, Persian and Arabic ţūfān (طوفان), which in turn originates from Greek tuphōn (Τυφών), a monster in Greek mythology responsible for hot winds. The related Portuguese word tufão, used in Portuguese for typhoons, is also derived from Greek tuphōn.

Another theory is that it may have come from the Chinese word "dafeng" (大風 - literally huge winds).

The word hurricane, used in the North Atlantic and Northeast Pacific, is derived from the name of a native Caribbean Amerindian storm god, Huracan, via Spanish huracán. (Huracan is also the source of the word Orcan, another word for the European windstorm. These events should not be confused.) Huracan became the Spanish term for hurricanes.

Naming

Main articles: Tropical cyclone naming and Lists of tropical cyclone namesStorms reaching tropical storm strength were initially given names to eliminate confusion when there are multiple systems in any individual basin at the same time, which assists in warning people of the coming storm. In most cases, a tropical cyclone retains its name throughout its life; however, under special circumstances, tropical cyclones may be renamed while active. These names are taken from lists that vary from region to region and are drafted a few years ahead of time. The lists are decided on, depending on the regions, either by committees of the World Meteorological Organization (called primarily to discuss many other issues), or by national weather offices involved in the forecasting of the storms. Each year, the names of particularly destructive storms (if there are any) are "retired" and new names are chosen to take their place.

Notable tropical cyclones

Main articles: List of notable tropical cyclones, List of Atlantic hurricanes, and List of Pacific hurricanesTropical cyclones that cause extreme destruction are rare, although when they occur, they can cause great amounts of damage or thousands of fatalities. The 1970 Bhola cyclone is the deadliest tropical cyclone on record, killing more than 300,000 people and potentially as many as 1 million after striking the densely populated Ganges Delta region of Bangladesh on 13 November 1970. Its powerful storm surge was responsible for the high death toll. The North Indian cyclone basin has historically been the deadliest basin. Elsewhere, Typhoon Nina killed nearly 100,000 in China due to a 2000-year flood that caused 62 dams including the Banqiao Dam to fail. The Great Hurricane of 1780 is the deadliest Atlantic hurricane on record, killing about 22,000 people in the Lesser Antilles. A tropical cyclone does need not be particularly strong to cause memorable damage, primarily if the deaths are from rainfall or mudslides. Tropical Storm Thelma in November 1991 killed thousands in the Philippines, while in 1982, the unnamed tropical depression that eventually became Hurricane Paul killed around 1,000 people in Central America.

Hurricane Katrina is estimated as the costliest tropical cyclone worldwide, causing $81.2 billion in property damage (2008 USD) with overall damage estimates exceeding $100 billion (2005 USD). Katrina killed at least 1,836 people after striking Louisiana and Mississippi as a major hurricane in August 2005. Hurricane Andrew is the second most destructive tropical cyclone in U.S history, with damages totaling $40.7 billion (2008 USD), and with damage costs at $31.5 billion (2008 USD), Hurricane Ike is the third most destructive tropical cyclone in U.S history. The Galveston Hurricane of 1900 is the deadliest natural disaster in the United States, killing an estimated 6,000 to 12,000 people in Galveston, Texas. Hurricane Iniki in 1992 was the most powerful storm to strike Hawaii in recorded history, hitting Kauai as a Category 4 hurricane, killing six people, and causing U.S. $3 billion in damage. Other destructive Eastern Pacific hurricanes include Pauline and Kenna, both causing severe damage after striking Mexico as major hurricanes. In March 2004, Cyclone Gafilo struck northeastern Madagascar as a powerful cyclone, killing 74, affecting more than 200,000, and becoming the worst cyclone to affect the nation for more than 20 years.

The most intense storm on record was Typhoon Tip in the northwestern Pacific Ocean in 1979, which reached a minimum pressure of 870 mbar (25.69 inHg) and maximum sustained wind speeds of 165 knots (85 m/s) or 190 miles per hour (310 km/h). Tip, however, does not solely hold the record for fastest sustained winds in a cyclone. Typhoon Keith in the Pacific and Hurricanes Camille and Allen in the North Atlantic currently share this record with Tip. Camille was the only storm to actually strike land while at that intensity, making it, with 165 knots (85 m/s) or 190 miles per hour (310 km/h) sustained winds and 183 knots (94 m/s) or 210 miles per hour (340 km/h) gusts, the strongest tropical cyclone on record at landfall. Typhoon Nancy in 1961 had recorded wind speeds of 185 knots (95 m/s) or 215 miles per hour (346 km/h), but recent research indicates that wind speeds from the 1940s to the 1960s were gauged too high, and this is no longer considered the storm with the highest wind speeds on record. Similarly, a surface-level gust caused by Typhoon Paka on Guam was recorded at 205 knots (105 m/s) or 235 miles per hour (378 km/h). Had it been confirmed, it would be the strongest non-tornadic wind ever recorded on the Earth's surface, but the reading had to be discarded since the anemometer was damaged by the storm.

In addition to being the most intense tropical cyclone on record, Tip was the largest cyclone on record, with tropical storm-force winds 2,170 kilometres (1,350 mi) in diameter. The smallest storm on record, Cyclone Tracy, was roughly 100 kilometres (62 mi) wide before striking Darwin, Australia in 1974.

Hurricane John is the longest-lasting tropical cyclone on record, lasting 31 days in 1994. Before the advent of satellite imagery in 1961, however, many tropical cyclones were underestimated in their durations. John is the second longest-tracked tropical cyclone in the Northern Hemisphere on record, behind Typhoon Ophelia of 1960, which had a path of 8,500 miles (12,500 km). Reliable data for Southern Hemisphere cyclones is unavailable.

Long-term activity trends

- See also: Atlantic hurricane reanalysis

While the number of storms in the Atlantic has increased since 1995, there is no obvious global trend; the annual number of tropical cyclones worldwide remains about 87 ± 10. However, the ability of climatologists to make long-term data analysis in certain basins is limited by the lack of reliable historical data in some basins, primarily in the Southern Hemisphere. In spite of that, there is some evidence that the intensity of hurricanes is increasing. Kerry Emanuel stated, "Records of hurricane activity worldwide show an upswing of both the maximum wind speed in and the duration of hurricanes. The energy released by the average hurricane (again considering all hurricanes worldwide) seems to have increased by around 70% in the past 30 years or so, corresponding to about a 15% increase in the maximum wind speed and a 60% increase in storm lifetime."

Atlantic storms are becoming more destructive financially, since five of the ten most expensive storms in United States history have occurred since 1990. According to the World Meteorological Organization, “recent increase in societal impact from tropical cyclones has largely been caused by rising concentrations of population and infrastructure in coastal regions.” Pielke et al. (2008) normalized mainland U.S. hurricane damage from 1900–2005 to 2005 values and found no remaining trend of increasing absolute damage. The 1970s and 1980s were notable because of the extremely low amounts of damage compared to other decades. The decade 1996–2005 was the second most damaging among the past 11 decades, with only the decade 1926–1935 surpassing its costs. The most damaging single storm is the 1926 Miami hurricane, with $157 billion of normalized damage.

Often in part because of the threat of hurricanes, many coastal regions had sparse population between major ports until the advent of automobile tourism; therefore, the most severe portions of hurricanes striking the coast may have gone unmeasured in some instances. The combined effects of ship destruction and remote landfall severely limit the number of intense hurricanes in the official record before the era of hurricane reconnaissance aircraft and satellite meteorology. Although the record shows a distinct increase in the number and strength of intense hurricanes, therefore, experts regard the early data as suspect.

The number and strength of Atlantic hurricanes may undergo a 50–70 year cycle, also known as the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation. Nyberg et al. reconstructed Atlantic major hurricane activity back to the early 18th century and found five periods averaging 3–5 major hurricanes per year and lasting 40–60 years, and six other averaging 1.5–2.5 major hurricanes per year and lasting 10–20years. These periods are associated with the Atlantic multidecadal oscillation. Throughout, a decadal oscillation related to solar irradiance was responsible for enhancing/dampening the number of major hurricanes by 1–2 per year.

Although more common since 1995, few above-normal hurricane seasons occurred during 1970–94. Destructive hurricanes struck frequently from 1926–60, including many major New England hurricanes. Twenty-one Atlantic tropical storms formed in 1933, a record only recently exceeded in 2005, which saw 28 storms. Tropical hurricanes occurred infrequently during the seasons of 1900–25; however, many intense storms formed during 1870–99. During the 1887 season, 19 tropical storms formed, of which a record 4 occurred after 1 November and 11 strengthened into hurricanes. Few hurricanes occurred in the 1840s to 1860s; however, many struck in the early 19th century, including an 1821 storm that made a direct hit on New York City. Some historical weather experts say these storms may have been as high as Category 4 in strength.

These active hurricane seasons predated satellite coverage of the Atlantic basin. Before the satellite era began in 1960, tropical storms or hurricanes went undetected unless a reconnaissance aircraft encountered one, a ship reported a voyage through the storm, or a storm hit land in a populated area. The official record, therefore, could miss storms in which no ship experienced gale-force winds, recognized it as a tropical storm (as opposed to a high-latitude extra-tropical cyclone, a tropical wave, or a brief squall), returned to port, and reported the experience.

Proxy records based on paleotempestological research have revealed that major hurricane activity along the Gulf of Mexico coast varies on timescales of centuries to millennia. Few major hurricanes struck the Gulf coast during 3000–1400 BC and again during the most recent millennium. These quiescent intervals were separated by a hyperactive period during 1400 BC and 1000 AD, when the Gulf coast was struck frequently by catastrophic hurricanes and their landfall probabilities increased by 3–5 times. This millennial-scale variability has been attributed to long-term shifts in the position of the Azores High, which may also be linked to changes in the strength of the North Atlantic Oscillation.

According to the Azores High hypothesis, an anti-phase pattern is expected to exist between the Gulf of Mexico coast and the Atlantic coast. During the quiescent periods, a more northeasterly position of the Azores High would result in more hurricanes being steered towards the Atlantic coast. During the hyperactive period, more hurricanes were steered towards the Gulf coast as the Azores High was shifted to a more southwesterly position near the Caribbean. Such a displacement of the Azores High is consistent with paleoclimatic evidence that shows an abrupt onset of a drier climate in Haiti around 3200 C years BP, and a change towards more humid conditions in the Great Plains during the late-Holocene as more moisture was pumped up the Mississippi Valley through the Gulf coast. Preliminary data from the northern Atlantic coast seem to support the Azores High hypothesis. A 3000-year proxy record from a coastal lake in Cape Cod suggests that hurricane activity increased significantly during the past 500–1000 years, just as the Gulf coast was amid a quiescent period of the last millennium.

Global warming

- See also: Effects of global warming

The U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory performed a simulation to determine if there is a statistical trend in the frequency or strength of tropical cyclones over time. The simulation concluded "the strongest hurricanes in the present climate may be upstaged by even more intense hurricanes over the next century as the earth's climate is warmed by increasing levels of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere".

In an article in Nature, Kerry Emanuel stated that potential hurricane destructiveness, a measure combining hurricane strength, duration, and frequency, "is highly correlated with tropical sea surface temperature, reflecting well-documented climate signals, including multidecadal oscillations in the North Atlantic and North Pacific, and global warming". Emanuel predicted "a substantial increase in hurricane-related losses in the twenty-first century". Similarly, P.J. Webster and others published an article in Science examining the "changes in tropical cyclone number, duration, and intensity" over the past 35 years, the period when satellite data has been available. Their main finding was although the number of cyclones decreased throughout the planet excluding the north Atlantic Ocean, there was a great increase in the number and proportion of very strong cyclones.

| Costliest U.S. Atlantic hurricanes, 1900–2017 Direct economic losses, normalized to societal conditions in 2018 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Hurricane | Season | Cost |

| 1 | 4 "Miami" | 1926 | $235.9 billion |

| 2 | 4 "Galveston" | 1900 | $138.6 billion |

| 3 | 3 Katrina | 2005 | $116.9 billion |

| 4 | 4 "Galveston" | 1915 | $109.8 billion |

| 5 | 5 Andrew | 1992 | $106.0 billion |

| 6 | ET Sandy | 2012 | $73.5 billion |

| 7 | 3 "Cuba–Florida" | 1944 | $73.5 billion |

| 8 | 4 Harvey | 2017 | $62.2 billion |

| 9 | 3 "New England" | 1938 | $57.8 billion |

| 10 | 4 "Okeechobee" | 1928 | $54.4 billion |

| Main article: List of costliest Atlantic hurricanes | |||

The strength of the reported effect is surprising in light of modeling studies that predict only a one half category increase in storm intensity as a result of a ~2 °C (3.6 °F) global warming. Such a response would have predicted only a ~10% increase in Emanuel's potential destructiveness index during the 20th century rather than the ~75–120% increase he reported. Secondly, after adjusting for changes in population and inflation, and despite a more than 100% increase in Emanuel's potential destructiveness index, no statistically significant increase in the monetary damages resulting from Atlantic hurricanes has been found.

Sufficiently warm sea surface temperatures are considered vital to the development of tropical cyclones. Although neither study can directly link hurricanes with global warming, the increase in sea surface temperatures is believed to be due to both global warming and nature variability, e.g. the hypothesized Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO), although an exact attribution has not been defined. However, recent temperatures are the warmest ever observed for many ocean basins.

In February 2007, the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change released its fourth assessment report on climate change. The report noted many observed changes in the climate, including atmospheric composition, global average temperatures, ocean conditions, among others. The report concluded the observed increase in tropical cyclone intensity is larger than climate models predict. Additionally, the report considered that it is likely that storm intensity will continue to increase through the 21st century, and declared it more likely than not that there has been some human contribution to the increases in tropical cyclone intensity. However, there is no universal agreement about the magnitude of the effects anthropogenic global warming has on tropical cyclone formation, track, and intensity. For example, critics such as Chris Landsea assert that man-made effects would be "quite tiny compared to the observed large natural hurricane variability". A statement by the American Meteorological Society on 1 February 2007 stated that trends in tropical cyclone records offer "evidence both for and against the existence of a detectable anthropogenic signal" in tropical cyclogenesis. Although many aspects of a link between tropical cyclones and global warming are still being "hotly debated", a point of agreement is that no individual tropical cyclone or season can be attributed to global warming. Research reported in the 3 September 2008 issue of Nature found that the strongest tropical cyclones are getting stronger, particularly over the North Atlantic and Indian oceans. Wind speeds for the strongest tropical storms increased from an average of 140 miles per hour (230 km/h) in 1981 to 156 miles per hour (251 km/h) in 2006, while the ocean temperature, averaged globally over the all regions where tropical cyclones form, increased from 28.2 °C (82.8 °F) to 28.5 °C (83.3 °F) during this period.

Related cyclone types

In addition to tropical cyclones, there are two other classes of cyclones within the spectrum of cyclone types. These kinds of cyclones, known as extratropical cyclones and subtropical cyclones, can be stages a tropical cyclone passes through during its formation or dissipation.

An extratropical cyclone is a storm that derives energy from horizontal temperature differences, which are typical in higher latitudes. A tropical cyclone can become extratropical as it moves toward higher latitudes if its energy source changes from heat released by condensation to differences in temperature between air masses; additionally, although not as frequently, an extratropical cyclone can transform into a subtropical storm, and from there into a tropical cyclone. From space, extratropical storms have a characteristic "comma-shaped" cloud pattern. Extratropical cyclones can also be dangerous when their low-pressure centers cause powerful winds and high seas.

A subtropical cyclone is a weather system that has some characteristics of a tropical cyclone and some characteristics of an extratropical cyclone. They can form in a wide band of latitudes, from the equator to 50°. Although subtropical storms rarely have hurricane-force winds, they may become tropical in nature as their cores warm. From an operational standpoint, a tropical cyclone is usually not considered to become subtropical during its extratropical transition.

Tropical cyclones in popular culture

Main article: Tropical cyclones in popular cultureIn popular culture, tropical cyclones have made appearances in different types of media, including films, books, television, music, and electronic games. The media can have tropical cyclones that are entirely fictional, or can be based on real events. For example, George Rippey Stewart's Storm, a best-seller published in 1941, is thought to have influenced meteorologists into giving female names to Pacific tropical cyclones. Another example is the hurricane in The Perfect Storm, which describes the sinking of the Andrea Gail by the 1991 Halloween Nor'easter. Also, hypothetical hurricanes have been featured in parts of the plots of series such as The Simpsons, Invasion, Family Guy, Seinfeld, CSI Miami, and Dawson's Creek. The 2004 film The Day After Tomorrow includes several mentions of actual tropical cyclones as well as featuring fantastical "hurricane-like" non-tropical Arctic storms.

See also

- Hurricane Alley

- Hypercane

- List of wettest tropical cyclones by country

- Secondary flow in tropical cyclones

|

|

| Cyclones and anticyclones of the world (centers of action) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concepts | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Anticyclone |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cyclone |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- Symonds, Steve (17 November 2003). "Highs and Lows". Wild Weather. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 2007-03-23.

- ^ Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, Hurricane Research Division. "Frequently Asked Questions: What is an extra-tropical cyclone?". NOAA. Retrieved 2007-03-23. Cite error: The named reference "AOML FAQ A7" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ National Weather Service (19 October 2005). "Tropical Cyclone Structure". JetStream - An Online School for Weather. National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2006-12-14.

- Pasch, Richard J. (28 September 2006). "Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Wilma: 15-25 October 2005" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2006-12-14.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Lander, Mark A. (1999). "A Tropical Cyclone with a Very Large Eye" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. 127 (1): 137. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1999)127<0137:ATCWAV>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved 2006-12-14.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Pasch, Richard J. and Lixion A. Avila (1999). "Atlantic Hurricane Season of 1996" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. 127 (5): 581–610. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1999)127<0581:AHSO>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved 2006-12-14.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - American Meteorological Society. "AMS Glossary: C". Glossary of Meteorology. Allen Press. Retrieved 2006-12-14.

- Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, Hurricane Research Division. "Frequently Asked Questions: What is a "CDO"?". NOAA. Retrieved 2007-03-23.

- Atlantic Oceanographic and Hurricane Research Division. "Frequently Asked Questions: What are "concentric eyewall cycles" (or "eyewall replacement cycles") and why do they cause a hurricane's maximum winds to weaken?". NOAA. Retrieved 2006-12-14.

- ^ Joint Typhoon Warning Center. Q: What is the average size of a tropical cyclone? Retrieved on 2007-07-04.

- Robert T. Merrill. A Comparison of Large and Small Tropical Cyclones. Retrieved on 2008-07-14.

- Bureau of Meteorology. Australian Government Bureau of Meteorology Retrieved on 2008-02-24.

- K. S. Liu and Johnny C. L. Chan (1999). "Size of Tropical Cyclones as Inferred from ERS-1 and ERS-2 Data". Monthly Weather Review. 127 (12): 2992. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1999)127<2992:SOTCAI>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved 2008-02-24.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Kerry Emanuel. Anthropogenic Effects on Tropical Cyclone Activity. Retrieved on 2008-02-25.

- ^ National Weather Service (2006). "Hurricanes... Unleashing Nature's Fury: A Preparedness Guide" (PDF). NOAA. Retrieved 2006-12-02.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, Hurricane Research Division. "Frequently Asked Questions: Why don't we try to destroy tropical cyclones by nuking them?". NOAA. Retrieved 2006-07-25. Cite error: The named reference "AOML FAQ C5c" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration (2001). "NOAA Question of the Month: How much energy does a hurricane release?". NOAA. Retrieved 2006-03-31.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Encyclopædia Britannica. Coriolis force (physics). Retrieved on 2008-02-25.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica. Tropical cyclone: Tropical cyclone tracks. Retrieved on 2008-02-25.

- ^ Bureau of Meteorology. "How are tropical cyclones different to mid-latitude cyclones?". Frequently Asked Questions. Retrieved 2006-03-31.

- Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, Hurricane Research Division. "Frequently Asked Questions: Doesn't the friction over land kill tropical cyclones?". NOAA. Retrieved 2006-07-25.

- ^ Eric A. D'Asaro and Peter G. Black. (2006). "J8.4 Turbulence in the Ocean Boundary Layer Below Hurricane Dennis" (PDF). University of Washington. Retrieved 2008-02-22.

- University Corporation for Atmospheric Research. Hurricanes: Keeping an eye on weather's biggest bullies. Retrieved on 2006-03-31.

- Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, Hurricane Research Division. "Frequently Asked Questions: What's it like to go through a hurricane on the ground? What are the early warning signs of an approaching tropical cyclone?". NOAA. Retrieved 2006-07-26.

- Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, Hurricane Research Division. "Frequently Asked Questions: What regions around the globe have tropical cyclones and who is responsible for forecasting there?". NOAA. Retrieved 2006-07-25.

- World Meteorological Organization (25 April 2006). "RSMCs". Tropical Cyclone Programme (TCP). Retrieved 2006-11-05.

- Joint Typhoon Warning Center. Joint Typhoon Warning Center Mission Statement. Retrieved on 2008-02-24.

- Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration. MISSION / VISION. Retrieved on 2008-02-24.

- Canadian Hurricane Centre. Canadian Hurricane Centre. Retrieved on 2008-02-24.

- Marcelino, Emerson Vieira; Isabela Pena Viana de Oliveira Marcelino; Frederico de Moraes Rudorff (2004). "Cyclone Catarina: Damage and Vulnerability Assessment" (PDF). Santa Catarina Federal University. Retrieved 2006-12-24.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, Hurricane Research Division. "Frequently Asked Questions: When is hurricane season?". NOAA. Retrieved 2006-07-25.

- McAdie, Colin (10 May 2007). "Tropical Cyclone Climatology". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-06-09.

- Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, Hurricane Research Division. "Frequently Asked Questions: What are the average, most, and least tropical cyclones occurring in each basin?". NOAA. Retrieved 2006-11-30.

- Simon Ross. Natural Hazards. Retrieved on 2008-02-24.

- ^ Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, Hurricane Research Division. "Frequently Asked Questions: How do tropical cyclones form?". NOAA. Retrieved 2006-07-26.

- Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, Hurricane Research Division. "Frequently Asked Questions: Why do tropical cyclones require 80 °F (27 °C) ocean temperatures to form?". NOAA. Retrieved 2006-07-25.

- Marine Knowledge Centre. Marine Meteorological Glossary: I. Retrieved on 2008-02-24.

- Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration. Formation of Tropical Cyclones. Retrieved on 2008-02-24.

- ^ DeCaria, Alex (2005). "Lesson 5 – Tropical Cyclones: Climatology". ESCI 344 – Tropical Meteorology. Millersville University. Retrieved 2008-02-22.

- ^ Avila, Lixion (1995). "Atlantic tropical systems of 1993" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. 123 (3): 887–896. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1995)123<0887:ATSO>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved 2006-07-25.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, Hurricane Research Division. "Frequently Asked Questions: What is an easterly wave?". NOAA. Retrieved 2006-07-25.

- Landsea, Chris (1993). "A Climatology of Intense (or Major) Atlantic Hurricanes" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. 121 (6): 1703–1713. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1993)121<1703:ACOIMA>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved 2006-03-25.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Neumann, Charles J. "Worldwide Tropical Cyclone Tracks 1979-88". Global Guide to Tropical Cyclone Forecasting. Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved 2006-12-12.

- Henderson-Sellers, H. Zhang, G. Berz, K. Emanuel, William Gray, Christopher Landsea, Greg Holland, J. Lighthill, S-L. Shieh, P. Webster, and K. McGuffie. Tropical Cyclones and Global Climate Change: A Post-IPCC Assessment. Retrieved on 2008-02-25.

- Gary Padgett. "Monthly Global Tropical Cyclone Summary, December 2001". Australian Severe Weather Index.

- Joint Typhoon Warning Center. 1.2 2004 North Indian Ocean Tropical Cyclones. Retrieved on 2008-02-24.

- ^ Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, Hurricane Research Division. "Frequently Asked Questions: What determines the movement of tropical cyclones?". NOAA. Retrieved 2006-07-25.

- Baum, Steven K. (20 January 1997). "The Glossary: Cn-Cz". Glossary of Oceanography and the Related Geosciences with References. Texas A&M University. Retrieved 2006-11-29.

- U. S. Navy. Section 2: Tropical Cyclone Motion Terminology. Retrieved on 2007-04-10.

- Powell, Jeff; et al. (2007). "Hurricane Ioke: 20-27 August 2006". 2006 Tropical Cyclones Central North Pacific. Central Pacific Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-06-09.

{{cite web}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ National Hurricane Center (2005). "Glossary of NHC/TPC Terms". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2006-11-29.

- "Fujiwhara effect describes a stormy waltz". USA Today. Retrieved 2008-02-21.

- National Hurricane Center. Subject : C2) Doesn't the friction over land kill tropical cyclones? Retrieved on 2008-02-25.

- Bureau of Meteorology. Tropical Cyclones Affecting Inland Pilbara towns. Retrieved on 2008-02-25.

- Yuh-Lang Lin, S. Chiao, J. A. Thurman, D. B. Ensley, and J. J. Charney. Some Common Ingredients for heavy Orographic Rainfall and their Potential Application for Prediction. Retrieved on 2007-04-26.

- National Hurricane Center (1998). NHC Mitch Report "Hurricane Mitch Tropical Cyclone Report". Retrieved 2006-04-20.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) - Joint Typhoon Warning Center. 1.13 Local Effects on the Observed Large-scale Circulations. Retrieved on 2008-02-25.

- Shay, Lynn K., Russell L. Elsberry and Peter G. Black (1989). "Vertical Structure of the Ocean Current Response to a Hurricane" (PDF). Journal of Physical Oceanography. 19 (5): 649. doi:10.1175/1520-0485(1989)019<0649:VSOTOC>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved 2006-12-12.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Edwards, Jonathan. "Tropical Cyclone Formation". HurricaneZone.net. Retrieved 2006-11-30.

- ^ Chih-Pei Chang (2004). East Asian Monsoon. World Scientific. ISBN 9812387692. OCLC 61353183.

- United States Naval Research Laboratory (23 September 1999). "Tropical Cyclone Intensity Terminology". Tropical Cyclone Forecasters' Reference Guide. Retrieved 2006-11-30.

- Rappaport, Edward N. (2 November 2000). "Preliminary Report: Hurricane Iris: 22-4 August September 1995". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2006-11-29.

- African Dust Linked To Hurricane Strength by Jon Hamilton. All Things Considered, NPR. 5 Sep 2008.

- Hurricane Research Division. Project STORMFURY. Retrieved on 2008-02-25.

- H. E. Willoughby, D. P. Jorgensen, R. A. Black, and S. L. Rosenthal. Project Stormfury: A Scientific Chronicle 1962-1983. Retrieved on 2008-02-25.

- Whipple, Addison (1982). Storm. Alexandria, VA: Time Life Books. p. 151. ISBN 0-8094-4312-0.

- Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, Hurricane Research Division. "Frequently Asked Questions: Why don't we try to destroy tropical cyclones by seeding them with silver iodide?". NOAA. Retrieved 2006-07-25.

- ^ Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, Hurricane Research Division. "Frequently Asked Questions: Why don't we try to destroy tropical cyclones by cooling the surface waters with icebergs or deep ocean water?". NOAA. Retrieved 2006-07-25.

- Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, Hurricane Research Division. "Frequently Asked Questions: Why don't we try to destroy tropical cyclones by placing a substance on the ocean surface?". NOAA. Retrieved 2006-07-25.

- Scotti, R. A. (2003). Sudden Sea: The Great Hurricane of 1938 (1st ed. ed.). Little, Brown, and Company. p. 47. ISBN 0-316-73911-1. OCLC 51861977.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, Hurricane Research Division. "Frequently Asked Questions: Why do not we try to destroy tropical cyclones by (fill in the blank)?". NOAA. Retrieved 2006-07-25.

- David Roth and Hugh Cobb (2001). "Eighteenth Century Virginia Hurricanes". NOAA. Retrieved 2007-02-24.

- James M. Shultz, Jill Russell and Zelde Espinel (2005). "Epidemiology of Tropical Cyclones: The Dynamics of Disaster, Disease, and Development". Oxford Journal. Retrieved 2007-02-24.

- Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, Hurricane Research Division. "Frequently Asked Questions: Are TC tornadoes weaker than midlatitude tornadoes?". NOAA. Retrieved 2006-07-25.

- ^ Shultz, James M., Jill Russell and Zelde Espinel (2005). "Epidemiology of Tropical Cyclones: The Dynamics of Disaster, Disease, and Development". Epidemiologic Reviews. 27 (1): 21–25. doi:10.1093/epirev/mxi011. PMID 15958424. Retrieved 2006-12-14.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Staff Writer (2005-08-30). "Hurricane Katrina Situation Report #11" (PDF). Office of Electricity Delivery and Energy Reliability (OE) United States Department of Energy. Retrieved 2007-02-24.

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 2005 Tropical Eastern North Pacific Hurricane Outlook. Retrieved on 2006-05-02.

- "Living With an Annual Disaster". Zurich Financial Services. July/August 2005. Retrieved 2006-11-29.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Christopherson, Robert W. (1992). Geosystems: An Introduction to Physical Geography. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company. pp. 222–224. ISBN 0-02-322443-6.

- Florida Coastal Monitoring Program. "Project Overview". University of Florida. Retrieved 2006-03-30.

- Central Pacific Hurricane Center. Observations. Retrieved on 2006-12-09.

- 403rd Wing. "The Hurricane Hunters". 53rd Weather Reconnaissance Squadron. Retrieved 2006-03-30.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Lee, Christopher. "Drone, Sensors May Open Path Into Eye of Storm". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2008-02-22.

- United States Navy. "Influences on Tropical Cyclone Motion". Retrieved 2007-04-10.

- National Hurricane Center (22 May 2006). "Annual average model track errors for Atlantic basin tropical cyclones for the period 1994-2005, for a homogeneous selection of "early" models". National Hurricane Center Forecast Verification. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2006-11-30.

- National Hurricane Center (22 May 2006). "Annual average official track errors for Atlantic basin tropical cyclones for the period 1989-2005, with least-squares trend lines superimposed". National Hurricane Center Forecast Verification. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2006-11-30.

- Central Pacific Hurricane Center (2004). "Hurricane John Preliminary Report". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2007-03-23.

- Bouchard, R. H. (1990). "A Climatology of Very Intense Typhoons: Or Where Have All the Super Typhoons Gone?" (PPT). Retrieved 2006-12-05.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, Hurricane Research Division. "Frequently Asked Questions: What are the upcoming tropical cyclone names?". NOAA. Retrieved 2006-12-11.

- ^ Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, Hurricane Research Division. "Frequently Asked Questions: Which is the most intense tropical cyclone on record?". NOAA. Retrieved 2006-07-25.

- National Hurricane Center. Subject: A1) What is a hurricane, typhoon, or tropical cyclone? Retrieved on 2008-02-25.

- Bureau of Meteorology. Global Guide to Tropical Cyclone Forecasting Retrieved on 2008-02-25.

- "Typhoon". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (4th ed. ed.). Dictionary.com. 2004. Retrieved 2006-12-14.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - "Disaster Controlled Vocabulary (VDC)" (PDF). Centro Regional de Información sobre Desastres (in English, Spanish, and Portuguese and French). Retrieved 2008-01-24.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, Hurricane Research Division. "Frequently Asked Questions: What is the origin of the word "hurricane"?". NOAA. Retrieved 2006-07-25.

- National Hurricane Center. Worldwide Tropical Cyclone Names. Retrieved on 2006-12-28.

- ^ Chris Landsea (1993). "Which tropical cyclones have caused the most deaths and most damage?". Hurricane Research Division. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- Lawson (1999). "South Asia: A history of destruction". British Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- Frank, Neil L. and S. A. Husain (1971). "The Deadliest Tropical Cyclone in History" (PDF). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 52 (6): 438–445. doi:10.1175/1520-0477(1971)052<0438:TDTCIH>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved 2006-12-14.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Linda J. Anderson-Berry. Fifth International Workshop on Tropycal Cyclones: Topic 5.1: Societal Impacts of Tropical Cyclones. Retrieved on 2008-02-26.

- National Hurricane Center (22 April 1997). "The Deadliest Atlantic Tropical Cyclones, 1492-1996". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2006-03-31.

- Joint Typhoon Warning Center. "Typhoon Thelma (27W)" (PDF). 1991 Annual Tropical Cyclone Report. Retrieved 2006-03-31.

- Gunther, E. B., R.L. Cross, and R.A. Wagoner (1983). "Eastern North Pacific Tropical Cyclones of 1982" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. 111 (5): 1080. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1983)111<1080:ENPTCO>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved 2006-03-31.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Earth Policy Institute (2006). "Hurricane Damages Sour to New Levels". United States Department of Commerce. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ Knabb, Richard D., Jamie R. Rhome and Daniel P. Brown (20 December 2005). "Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Katrina: 23-30 August 2005" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2006-05-30.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - National Hurricane Center. Galveston Hurricane 1900. Retrieved on 2008-02-24.

- Central Pacific Hurricane Center. "Hurricane Iniki Natural Disaster Survey Report". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2006-03-31.

- Lawrence, Miles B. (7 November 1997). "Preliminary Report: Hurricane Pauline: 5-10 October 1997". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2006-03-31.

- Franklin, James L. (26 December 2002). "Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Kenna: 22-26 October 2002". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2006-03-31.

- World Food Programme (2004). "WFP Assists Cyclone And Flood Victims in Madagascar". Retrieved 2007-02-24.

- George M. Dunnavan & John W. Dierks (1980). "An Analysis of Super Typhoon Tip (October 1979)" (PDF). Joint Typhoon Warning Center. Retrieved 2007-01-24.

- Ferrell, Jesse (26 October 1998). "Hurricane Mitch". Weathermatrix.net. Retrieved 2006-03-30.

- NHC Hurricane Research Division (2006-02-17). "Atlantic hurricane best track ("HURDAT")". NOAA. Retrieved 2007-02-22.

- Houston, Sam, Greg Forbes and Arthur Chiu (17 August 1998). "Super Typhoon Paka's (1997) Surface Winds Over Guam". National Weather Service. Retrieved 2006-03-30.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, Hurricane Research Division. "Frequently Asked Questions: Which are the largest and smallest tropical cyclones on record?". NOAA. Retrieved 2006-07-25.

- Neal Dorst (2006). "Which tropical cyclone lasted the longest?". Hurricane Research Division. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- Neal Dorst (2006). "What is the farthest a tropical cyclone has traveled ?". Hurricane Research Division. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- Landsea, Chris; et al. (28 July 2006). "Can We Detect Trends in Extreme Tropical Cyclones?" (PDF). Science. 313: 452–454. doi:10.1126/science.1128448. PMID 16873634. Retrieved 2007-06-09.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - Emanuel, Kerry (2006). "Anthropogenic Effects on Tropical Cyclone Activity". Retrieved 2006-03-30.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - "Summary Statement on Tropical Cyclones and Climate Change" (PDF) (Press release). World Meteorological Organization. 2006-12-04.