| Revision as of 21:17, 8 February 2009 view sourceStevenfruitsmaak (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users11,785 edits add ref for diagonal ear lobe crease (Frank's sign) in MI← Previous edit | Revision as of 03:15, 9 February 2009 view source ParaGreen13 (talk | contribs)543 edits Qualifying non-medical statistical reasoning.Next edit → | ||

| Line 51: | Line 51: | ||

| Many of these risk factors are modifiable, so many heart attacks can be prevented by maintaining a healthier lifestyle. Physical activity, for example, is associated with a lower risk profile.<ref name="Jensen-1991">{{cite journal | author=Jensen G, Nyboe J, Appleyard M, Schnohr P. | title=Risk factors for acute myocardial infarction in Copenhagen, II: Smoking, alcohol intake, physical activity, obesity, oral contraception, diabetes, lipids, and blood pressure | journal=Eur Heart J | year=1991 | volume=12 | issue=3 | pages=298–308 | pmid=2040311}}</ref> Non-modifiable risk factors include age, sex, and family history of an early heart attack (before the age of 60), which is thought of as reflecting a ].<ref name="Framingham1998"/> | Many of these risk factors are modifiable, so many heart attacks can be prevented by maintaining a healthier lifestyle. Physical activity, for example, is associated with a lower risk profile.<ref name="Jensen-1991">{{cite journal | author=Jensen G, Nyboe J, Appleyard M, Schnohr P. | title=Risk factors for acute myocardial infarction in Copenhagen, II: Smoking, alcohol intake, physical activity, obesity, oral contraception, diabetes, lipids, and blood pressure | journal=Eur Heart J | year=1991 | volume=12 | issue=3 | pages=298–308 | pmid=2040311}}</ref> Non-modifiable risk factors include age, sex, and family history of an early heart attack (before the age of 60), which is thought of as reflecting a ].<ref name="Framingham1998"/> | ||

| ] factors such as a shorter ] and lower ] (particularly in women), and unmarried cohabitation may also contribute to the risk of MI.<ref name="Nyboe-1989">{{cite journal | author=Nyboe J, Jensen G, Appleyard M, Schnohr P. | title=Risk factors for acute myocardial infarction in Copenhagen. I: Hereditary, educational and socioeconomic factors. Copenhagen City Heart Study | journal=Eur Heart J | year=1989 | volume=10 | issue=10 | pages=910–6 | pmid=2598948}}</ref> To understand epidemiological study results, it's important to note that many factors associated with MI mediate their risk via other factors. For example, the effect of education is partially based on its effect on income and ].<ref name="Nyboe-1989"/> | ] factors such as a shorter ] and lower ] (particularly in women), and unmarried cohabitation may also contribute to the risk of MI.<ref name="Nyboe-1989">{{cite journal | author=Nyboe J, Jensen G, Appleyard M, Schnohr P. | title=Risk factors for acute myocardial infarction in Copenhagen. I: Hereditary, educational and socioeconomic factors. Copenhagen City Heart Study | journal=Eur Heart J | year=1989 | volume=10 | issue=10 | pages=910–6 | pmid=2598948}}</ref> To understand epidemiological study results, it's important to note that many factors associated with MI mediate their risk via other factors. For example, the effect of education is partially based on its effect on income and ].<ref name="Nyboe-1989"/> This is all statistical, like factors for insurance policies. None of these things actually puts a person at a higher risk for heart attacks. It's speculation. What this is based on is the idea that if someone is less schooled, they will eat improperly since they won't know as much about nutrition or their thinking shall be more limited. If someone makes less money, they must have a worse job, therefore they are less educated, etc. Also, if they cohabitate instead of being married, then there might be more random sex then more VD, or just a more radical lifestyle. All of these things are assumptions and not medical science. They ought to be excluded since the logic is entirerly questionable. | ||

| Women who use ]s have a modestly increased risk of myocardial infarction, especially in the presence of other risk factors, such as smoking.<ref name="Khader-2003">{{cite journal | author=Khader YS, Rice J, John L, Abueita O. | title=Oral contraceptives use and the risk of myocardial infarction: a meta-analysis | journal=Contraception | year=2003 | volume=68 | issue=1 | pages=11–7 | pmid=12878281 | doi = 10.1016/S0010-7824(03)00073-8}}</ref> | Women who use ]s have a modestly increased risk of myocardial infarction, especially in the presence of other risk factors, such as smoking.<ref name="Khader-2003">{{cite journal | author=Khader YS, Rice J, John L, Abueita O. | title=Oral contraceptives use and the risk of myocardial infarction: a meta-analysis | journal=Contraception | year=2003 | volume=68 | issue=1 | pages=11–7 | pmid=12878281 | doi = 10.1016/S0010-7824(03)00073-8}}</ref> | ||

Revision as of 03:15, 9 February 2009

"Heart attack" redirects here. For other uses, see Heart attack (disambiguation). Medical condition| Myocardial infarction | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Cardiology |

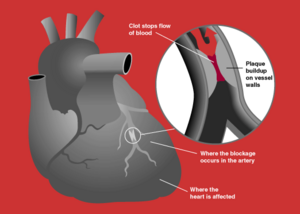

Myocardial infarction (MI or AMI for acute myocardial infarction), commonly known as a heart attack, occurs when the blood supply to part of the heart is interrupted. This is most commonly due to occlusion (blockage) of a coronary artery following the rupture of a vulnerable atherosclerotic plaque, which is an unstable collection of lipids (like cholesterol) and white blood cells (especially macrophages) in the wall of an artery. The resulting ischemia (restriction in blood supply) and oxygen shortage, if left untreated for a sufficient period, can cause damage and/or death (infarction) of heart muscle tissue (myocardium).

Classical symptoms of acute myocardial infarction include sudden chest pain (typically radiating to the left arm or left side of the neck), shortness of breath, nausea, vomiting, palpitations, sweating, and anxiety (often described as a sense of impending doom). Women may experience fewer typical symptoms than men, most commonly shortness of breath, weakness, a feeling of indigestion, and fatigue. Approximately one quarter of all myocardial infarctions are silent, without chest pain or other symptoms. A heart attack is a medical emergency, and people experiencing chest pain are advised to alert their emergency medical services, because prompt treatment is beneficial.

Heart attacks are the leading cause of death for both men and women all over the world. Important risk factors are previous cardiovascular disease (such as angina, a previous heart attack or stroke), older age (especially men over 40 and women over 50), tobacco smoking, high blood levels of certain lipids (triglycerides, low-density lipoprotein or "bad cholesterol") and low high density lipoprotein (HDL, "good cholesterol"), diabetes, high blood pressure, obesity, chronic kidney disease, heart failure, excessive alcohol consumption, the abuse of certain drugs (such as cocaine), and chronic high stress levels.

Immediate treatment for suspected acute myocardial infarction includes oxygen, aspirin, and sublingual glyceryl trinitrate (colloquially referred to as nitroglycerin and abbreviated as NTG or GTN). Pain relief is also often given, classically morphine sulfate.

The patient will receive a number of diagnostic tests, such as an electrocardiogram (ECG, EKG), a chest X-ray and blood tests to detect elevations in cardiac markers (blood tests to detect heart muscle damage). The most often used markers are the creatine kinase-MB (CK-MB) fraction and the troponin I (TnI) or troponin T (TnT) levels. On the basis of the ECG, a distinction is made between ST elevation MI (STEMI) or non-ST elevation MI (NSTEMI). Most cases of STEMI are treated with thrombolysis or if possible with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI, angioplasty and stent insertion), provided the hospital has facilities for coronary angiography. NSTEMI is managed with medication, although PCI is often performed during hospital admission. In patients who have multiple blockages and who are relatively stable, or in a few extraordinary emergency cases, bypass surgery of the blocked coronary artery is an option.

The phrase "heart attack" is sometimes used incorrectly to describe sudden cardiac death, which may or may not be the result of acute myocardial infarction. A heart attack is different from, but can be the cause of cardiac arrest, which is the stopping of the heartbeat, and cardiac arrhythmia, an abnormal heartbeat. It is also distinct from heart failure, in which the pumping action of the heart is impaired; severe myocardial infarction may lead to heart failure, but not necessarily.

Epidemiology

Myocardial infarction is a common presentation of ischemic heart disease. The WHO estimated that in 2002, 12.6 percent of deaths worldwide were from ischemic heart disease. Ischemic heart disease is the leading cause of death in developed countries, but third to AIDS and lower respiratory infections in developing countries.

In the United States, diseases of the heart are the leading cause of death, causing a higher mortality than cancer (malignant neoplasms). Coronary heart disease is responsible for 1 in 5 deaths in the U.S.. Some 7,200,000 men and 6,000,000 women are living with some form of coronary heart disease. 1,200,000 people suffer a (new or recurrent) coronary attack every year, and about 40% of them die as a result of the attack. This means that roughly every 65 seconds, an American dies of a coronary event.

In India, cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death. The deaths due to CVD in India were 32% of all deaths in 2007 and are expected to rise from 1.17 million in 1990 and 1.59 million in 2000 to 2.03 million in 2010. Although a relatively new epidemic in India, it has quickly become a major health issue with deaths due to CVD expected to double during 1985-2015. Mortality estimates due to CVD vary widely by state, ranging from 10% in Meghalaya to 49% in Punjab (percentage of all deaths). Punjab (49%), Goa (42%), Tamil Nadu (36%) and Andhra Pradesh (31%) have the highest CVD related mortality estimates. State-wise differences are correlated with prevalence of specific dietary risk factors in the states. Moderate physical exercise is associated with reduced incidence of CVD in India (those who exercise have less than half the risk of those who don't). CVD also affects Indians at a younger age (in their 30s and 40s) than is typical in other countries.

Risk factors

Risk factors for atherosclerosis are generally risk factors for myocardial infarction:

- Older age

- Male sex

- Tobacco smoking

- Hypercholesterolemia (more accurately hyperlipoproteinemia, especially high low density lipoprotein and low high density lipoprotein)

- Hyperhomocysteinemia (high homocysteine, a toxic blood amino acid that is elevated when intakes of vitamins B2, B6, B12 and folic acid are insufficient)

- Diabetes (with or without insulin resistance)

- High blood pressure

- Obesity (defined by a body mass index of more than 30 kg/m², or alternatively by waist circumference or waist-hip ratio).

- Stress Occupations with high stress index are known to have susceptibility for atherosclerosis.

Many of these risk factors are modifiable, so many heart attacks can be prevented by maintaining a healthier lifestyle. Physical activity, for example, is associated with a lower risk profile. Non-modifiable risk factors include age, sex, and family history of an early heart attack (before the age of 60), which is thought of as reflecting a genetic predisposition.

Socioeconomic factors such as a shorter education and lower income (particularly in women), and unmarried cohabitation may also contribute to the risk of MI. To understand epidemiological study results, it's important to note that many factors associated with MI mediate their risk via other factors. For example, the effect of education is partially based on its effect on income and marital status. This is all statistical, like factors for insurance policies. None of these things actually puts a person at a higher risk for heart attacks. It's speculation. What this is based on is the idea that if someone is less schooled, they will eat improperly since they won't know as much about nutrition or their thinking shall be more limited. If someone makes less money, they must have a worse job, therefore they are less educated, etc. Also, if they cohabitate instead of being married, then there might be more random sex then more VD, or just a more radical lifestyle. All of these things are assumptions and not medical science. They ought to be excluded since the logic is entirerly questionable.

Women who use combined oral contraceptive pills have a modestly increased risk of myocardial infarction, especially in the presence of other risk factors, such as smoking.

Inflammation is known to be an important step in the process of atherosclerotic plaque formation. C-reactive protein (CRP) is a sensitive but non-specific marker for inflammation. Elevated CRP blood levels, especially measured with high sensitivity assays, can predict the risk of MI, as well as stroke and development of diabetes. Moreover, some drugs for MI might also reduce CRP levels. The use of high sensitivity CRP assays as a means of screening the general population is advised against, but it may be used optionally at the physician's discretion, in patients who already present with other risk factors or known coronary artery disease. Whether CRP plays a direct role in atherosclerosis remains uncertain.

Inflammation in periodontal disease may be linked coronary heart disease, and since periodontitis is very common, this could have great consequences for public health. Serological studies measuring antibody levels against typical periodontitis-causing bacteria found that such antibodies were more present in subjects with coronary heart disease. Periodontitis tends to increase blood levels of CRP, fibrinogen and cytokines; thus, periodontitis may mediate its effect on MI risk via other risk factors. Preclinical research suggests that periodontal bacteria can promote aggregation of platelets and promote the formation of foam cells. A role for specific periodontal bacteria has been suggested but remains to be established.

Baldness, hair greying, a diagonal earlobe crease (Frank's sign) and possibly other skin features have been suggested as independent risk factors for MI. Their role remains controversial; a common denominator of these signs and the risk of MI is supposed, possibly genetic.

Calcium deposition is another part of atherosclerotic plaque formation. Calcium deposits in the coronary arteries can be detected with CT scans. Several studies have shown that coronary calcium can provide predictive information beyond that of classical risk factors.

Pathophysiology

Acute myocardial infarction refers to two subtypes of acute coronary syndrome, namely non-ST-elevated myocardial infarction and ST-elevated myocardial infarction, which are most frequently (but not always) a manifestation of coronary artery disease. The most common triggering event is the disruption of an atherosclerotic plaque in an epicardial coronary artery, which leads to a clotting cascade, sometimes resulting in total occlusion of the artery. Atherosclerosis is the gradual buildup of cholesterol and fibrous tissue in plaques in the wall of arteries (in this case, the coronary arteries), typically over decades. Blood stream column irregularities visible on angiography reflect artery lumen narrowing as a result of decades of advancing atherosclerosis. Plaques can become unstable, rupture, and additionally promote a thrombus (blood clot) that occludes the artery; this can occur in minutes. When a severe enough plaque rupture occurs in the coronary vasculature, it leads to myocardial infarction (necrosis of downstream myocardium).

If impaired blood flow to the heart lasts long enough, it triggers a process called the ischemic cascade; the heart cells die (chiefly through necrosis) and do not grow back. A collagen scar forms in its place. Recent studies indicate that another form of cell death called apoptosis also plays a role in the process of tissue damage subsequent to myocardial infarction. As a result, the patient's heart will be permanently damaged. This scar tissue also puts the patient at risk for potentially life threatening arrhythmias, and may result in the formation of a ventricular aneurysm that can rupture with catastrophic consequences.

Injured heart tissue conducts electrical impulses more slowly than normal heart tissue. The difference in conduction velocity between injured and uninjured tissue can trigger re-entry or a feedback loop that is believed to be the cause of many lethal arrhythmias. The most serious of these arrhythmias is ventricular fibrillation (V-Fib/VF), an extremely fast and chaotic heart rhythm that is the leading cause of sudden cardiac death. Another life threatening arrhythmia is ventricular tachycardia (V-Tach/VT), which may or may not cause sudden cardiac death. However, ventricular tachycardia usually results in rapid heart rates that prevent the heart from pumping blood effectively. Cardiac output and blood pressure may fall to dangerous levels, which can lead to further coronary ischemia and extension of the infarct.

The cardiac defibrillator is a device that was specifically designed to terminate these potentially fatal arrhythmias. The device works by delivering an electrical shock to the patient in order to depolarize a critical mass of the heart muscle, in effect "rebooting" the heart. This therapy is time dependent, and the odds of successful defibrillation decline rapidly after the onset of cardiopulmonary arrest.

Triggers

Heart attack rates are higher in association with intense exertion, be it psychological stress or physical exertion, especially if the exertion is more intense than the individual usually performs. Quantitatively, the period of intense exercise and subsequent recovery is associated with about a 6-fold higher myocardial infarction rate (compared with other more relaxed time frames) for people who are physically very fit. For those in poor physical condition, the rate differential is over 35-fold higher. One observed mechanism for this phenomenon is the increased arterial pulse pressure stretching and relaxation of arteries with each heart beat which, as has been observed with intravascular ultrasound, increases mechanical "shear stress" on atheromas and the likelihood of plaque rupture.

Acute severe infection, such as pneumonia, can trigger myocardial infarction. A more controversial link is that between Chlamydophila pneumoniae infection and atherosclerosis. While this intracellular organism has been demonstrated in atherosclerotic plaques, evidence is inconclusive as to whether it can be considered a causative factor. Treatment with antibiotics in patients with proven atherosclerosis has not demonstrated a decreased risk of heart attacks or other coronary vascular diseases.

There is an association of an increased incidence of a heart attack in the morning hours, more specifically around 9 a.m. . Some investigators have noticed that the ability of platelets to aggregate varies according to a circadian rhythm, although they have not proven causation. Some investigators theorize that this increased incidence may be related to the circadian variation in cortisol production affecting the concentrations of various cytokines and other mediators of inflammation.

Classification

Acute myocardial infarction is a type of acute coronary syndrome, which is most frequently (but not always) a manifestation of coronary artery disease. The acute coronary syndromes include ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), and unstable angina (UA).

By zone

Depending on the location of the obstruction in the coronary circulation, different zones of the heart can become injured. Using the anatomical terms of location corresponding to areas perfused by major coronary arteries, one can describe anterior, inferior, lateral, apical, septal, posterior, and right-ventricular infarctions (and combinations, such as anteroinferior, anterolateral, and so on).

- For example, an occlusion of the left anterior descending coronary artery(LAD) will result in an anterior wall myocardial infarct.

- Infarcts of the lateral wall are caused by occlusion of the left circumflex coronary artery(LCx) or its oblique marginal branches (or even large diagonal branches from the LAD.)

- Both inferior wall and posterior wall infarctions may be caused by occlusion of either the right coronary artery or the left circumflex artery, depending on which feeds the posterior descending artery.

- Right ventricular wall infarcts are also caused by right coronary artery occlusion.

Subendocardial vs. transmural

Another distinction is whether a MI is subendocardial, affecting only the inner third to one half of the heart muscle, or transmural, damaging (almost) the entire wall of the heart. The inner part of the heart muscle is more vulnerable to oxygen shortage, because the coronary arteries run inward from the epicardium to the endocardium, and because the blood flow through the heart muscle is hindered by the heart contraction.

The phrases transmural and subendocardial infarction were previously considered synonymous with Q-wave and non-Q-wave myocardial infarction respectively, based on the presence or absence of Q waves on the ECG. It has since been shown that there is no clear correlation between the presence of Q waves with a transmural infarction and the absence of Q waves with a subendocardial infarction, but Q waves are associated with larger infarctions, while the lack of Q waves is associated with smaller infarctions. The presence or absence of Q-waves also has clinical importance, with improved outcomes associated with a lack of Q waves.

Symptoms

The onset of symptoms in myocardial infarction (MI) is usually gradual, over several minutes, and rarely instantaneous. Chest pain is the most common symptom of acute myocardial infarction and is often described as a sensation of tightness, pressure, or squeezing. Chest pain due to ischemia (a lack of blood and hence oxygen supply) of the heart muscle is termed angina pectoris. Pain radiates most often to the left arm, but may also radiate to the lower jaw, neck, right arm, back, and epigastrium, where it may mimic heartburn. Levine's sign, in which the patient localizes the chest pain by clenching their fist over the sternum, has classically been thought to be predictive of cardiac chest pain, although a prospective observational study showed that it had a poor positive predictive value.

Shortness of breath (dyspnea) occurs when the damage to the heart limits the output of the left ventricle, causing left ventricular failure and consequent pulmonary edema. Other symptoms include diaphoresis (an excessive form of sweating), weakness, light-headedness, nausea, vomiting, and palpitations. These symptoms are likely induced by a massive surge of catecholamines from the sympathetic nervous system which occurs in response to pain and the hemodynamic abnormalities that result from cardiac dysfunction. Loss of consciousness (due to inadequate cerebral perfusion and cardiogenic shock) and even sudden death (frequently due to the development of ventricular fibrillation) can occur in myocardial infarctions.

Women and older patients experience atypical symptoms more frequently than their male and younger counterparts. Women also have more symptoms compared to men (2.6 on average vs 1.8 symptoms in men). The most common symptoms of MI in women include dyspnea, weakness, and fatigue. Fatigue, sleep disturbances, and dyspnea have been reported as frequently occurring symptoms which may manifest as long as one month before the actual clinically manifested ischemic event. In women, chest pain may be less predictive of coronary ischemia than in men.

Approximately half of all MI patients have experienced warning symptoms such as chest pain prior to the infarction.

Approximately one fourth of all myocardial infarctions are silent, without chest pain or other symptoms. These cases can be discovered later on electrocardiograms or at autopsy without a prior history of related complaints. A silent course is more common in the elderly, in patients with diabetes mellitus and after heart transplantation, probably because the donor heart is not connected to nerves of the host. In diabetics, differences in pain threshold, autonomic neuropathy, and psychological factors have been cited as possible explanations for the lack of symptoms.

Any group of symptoms compatible with a sudden interruption of the blood flow to the heart are called an acute coronary syndrome.

The differential diagnosis includes other catastrophic causes of chest pain, such as pulmonary embolism, aortic dissection, pericardial effusion causing cardiac tamponade, tension pneumothorax, and esophageal rupture.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of myocardial infarction is made by integrating the history of the presenting illness and physical examination with electrocardiogram findings and cardiac markers (blood tests for heart muscle cell damage). A coronary angiogram allows visualization of narrowings or obstructions on the heart vessels, and therapeutic measures can follow immediately. At autopsy, a pathologist can diagnose a myocardial infarction based on anatomopathological findings.

A chest radiograph and routine blood tests may indicate complications or precipitating causes and are often performed upon arrival to an emergency department. New regional wall motion abnormalities on an echocardiogram are also suggestive of a myocardial infarction. Echo may be performed in equivocal cases by the on-call cardiologist. In stable patients whose symptoms have resolved by the time of evaluation, technetium-99m 2-methoxyisobutylisonitrile (Tc99m MIBI) or thallium-201 chloride can be used in nuclear medicine to visualize areas of reduced blood flow in conjunction with physiologic or pharmocologic stress. Thallium may also be used to determine viability of tissue, distinguishing whether non-functional myocardium is actually dead or merely in a state of hibernation or of being stunned.

Diagnostic criteria

WHO criteria have classically been used to diagnose MI; a patient is diagnosed with myocardial infarction if two (probable) or three (definite) of the following criteria are satisfied:

- Clinical history of ischaemic type chest pain lasting for more than 20 minutes

- Changes in serial ECG tracings

- Rise and fall of serum cardiac biomarkers such as creatine kinase-MB fraction and troponin

The WHO criteria were refined in 2000 to give more prominence to cardiac biomarkers. According to the new guidelines, a cardiac troponin rise accompanied by either typical symptoms, pathological Q waves, ST elevation or depression or coronary intervention are diagnostic of MI.

Physical examination

The general appearance of patients may vary according to the experienced symptoms; the patient may be comfortable, or restless and in severe distress with an increased respiratory rate. A cool and pale skin is common and points to vasoconstriction. Some patients have low-grade fever (38–39 °C). Blood pressure may be elevated or decreased, and the pulse can be become irregular.

If heart failure ensues, elevated jugular venous pressure and hepatojugular reflux, or swelling of the legs due to peripheral edema may be found on inspection. Rarely, a cardiac bulge with a pace different from the pulse rhythm can be felt on precordial examination. Various abnormalities can be found on auscultation, such as a third and fourth heart sound, systolic murmurs, paradoxical splitting of the second heart sound, a pericardial friction rub and rales over the lung.

Electrocardiogram

Main article: ElectrocardiogramThe primary purpose of the electrocardiogram is to detect ischemia or acute coronary injury in broad, symptomatic emergency department populations. However, the standard 12 lead ECG has several limitations. An ECG represents a brief sample in time. Because unstable ischemic syndromes have rapidly changing supply versus demand characteristics, a single ECG may not accurately represent the entire picture. It is therefore desirable to obtain serial 12 lead ECGs, particularly if the first ECG is obtained during a pain-free episode. Alternatively, many emergency departments and chest pain centers use computers capable of continuous ST segment monitoring. The standard 12 lead ECG also does not directly examine the right ventricle, and is relatively poor at examining the posterior basal and lateral walls of the left ventricle. In particular, acute myocardial infarction in the distribution of the circumflex artery is likely to produce a nondiagnostic ECG. The use of additional ECG leads like right-sided leads V3R and V4R and posterior leads V7, V8, and V9 may improve sensitivity for right ventricular and posterior myocardial infarction. In spite of these limitations, the 12 lead ECG stands at the center of risk stratification for the patient with suspected acute myocardial infarction. Mistakes in interpretation are relatively common, and the failure to identify high risk features has a negative effect on the quality of patient care.

The 12 lead ECG is used to classify patients into one of three groups:

- those with ST segment elevation or new bundle branch block (suspicious for acute injury and a possible candidate for acute reperfusion therapy with thrombolytics or primary PCI),

- those with ST segment depression or T wave inversion (suspicious for ischemia), and

- those with a so-called non-diagnostic or normal ECG.

A normal ECG does not rule out acute myocardial infarction. Sometimes the earliest presentation of acute myocardial infarction is the hyperacute T wave, which is treated the same as ST segment elevation. In practice this is rarely seen, because it only exists for 2-30 minutes after the onset of infarction. Hyperacute T waves need to be distinguished from the peaked T waves associated with hyperkalemia. The current guidelines for the ECG diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction require at least 1 mm (0.1 mV) of ST segment elevation in the limb leads, and at least 2 mm elevation in the precordial leads. These elevations must be present in anatomically contiguous leads. (I, aVL, V5, V6 correspond to the lateral wall; V1-V4 correspond to the anterior wall; II, III, aVF correspond to the inferior wall.) This criterion is problematic, however, as acute myocardial infarction is not the most common cause of ST segment elevation in chest pain patients. Over 90% of healthy men have at least 1 mm (0.1 mV) of ST segment elevation in at least one precordial lead. The clinician must therefore be well versed in recognizing the so-called ECG mimics of acute myocardial infarction, which include left ventricular hypertrophy, left bundle branch block, paced rhythm, early repolarization, pericarditis, hyperkalemia, and ventricular aneurysm.

Left bundle branch block and pacing interferes with the electrocardiographic diagnosis of acute myocadial infarction. The GUSTO investigators Sgarbossa et al. developed a set of criteria for identifying acute myocardial infarction in the presence of left bundle branch block and paced rhythm. They include concordant ST segment elevation > 1 mm (0.1 mV), discordant ST segment elevation > 5 mm (0.5 mV), and concordant ST segment depression in the left precordial leads. The presence of reciprocal changes on the 12 lead ECG may help distinguish true acute myocardial infarction from the mimics of acute myocardial infarction. The contour of the ST segment may also be helpful, with a straight or upwardly convex (non-concave) ST segment favoring the diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction.

The constellation of leads with ST segment elevation enables the clinician to identify what area of the heart is injured, which in turn helps predict the culprit artery.

| Wall Affected | Leads Showing ST Segment Elevation | Leads Showing Reciprocal ST Segment Depression | Suspected Culprit Artery |

|---|---|---|---|

| Septal | V1, V2 | None | Left Anterior Descending (LAD) |

| Anterior | V3, V4 | None | Left Anterior Descending (LAD) |

| Anteroseptal | V1, V2, V3, V4 | None | Left Anterior Descending (LAD) |

| Anterolateral | V3, V4, V5, V6, I, aVL | II, III, aVF | Left Anterior Descending (LAD), Circumflex (LCX), or Obtuse Marginal |

| Extensive anterior (Sometimes called Anteroseptal with Lateral extension) | V1,V2,V3, V4, V5, V6, I, aVL | II, III, aVF | Left main coronary artery (LCA) |

| Inferior | II, III, aVF | I, aVL | Right Coronary Artery (RCA) or Circumflex (LCX) |

| Lateral | I, aVL, V5, V6 | II, III, aVF | Circumflex (LCX) or Obtuse Marginal |

| Posterior (Usually associated with Inferior or Lateral but can be isolated) | V7, V8, V9 | V1,V2,V3, V4 | Posterior Descending (PDA) (branch of the RCA or Circumflex (LCX)) |

| Right ventricular (Usually associated with Inferior) | II, III, aVF, V1, V4R | I, aVL | Right Coronary Artery (RCA) |

As the myocardial infarction evolves, there may be loss of R wave height and development of pathological Q waves (defined as Q waves deeper than 1 mm and wider than 1 mm.) T wave inversion may persist for months or even permanently following acute myocardial infarction. Typically, however, the T wave recovers, leaving a pathological Q wave as the only remaining evidence that an acute myocardial infarction has occurred.

Cardiac markers

Main article: Cardiac markerCardiac markers or cardiac enzymes are proteins from cardiac tissue found in the blood. These proteins are released into the bloodstream when damage to the heart occurs, as in the case of a myocardial infarction. Until the 1980s, the enzymes SGOT and LDH were used to assess cardiac injury. Then it was found that disproportional elevation of the MB subtype of the enzyme creatine kinase (CK) was very specific for myocardial injury. Current guidelines are generally in favor of troponin sub-units I or T, which are very specific for the heart muscle and are thought to rise before permanent injury develops. Elevated troponins in the setting of chest pain may accurately predict a high likelihood of a myocardial infarction in the near future. New markers such as glycogen phosphorylase isoenzyme BB are under investigation.

The diagnosis of myocardial infarction requires two out of three components (history, ECG, and enzymes). When damage to the heart occurs, levels of cardiac markers rise over time, which is why blood tests for them are taken over a 24-hour period. Because these enzyme levels are not elevated immediately following a heart attack, patients presenting with chest pain are generally treated with the assumption that a myocardial infarction has occurred and then evaluated for a more precise diagnosis.

Angiography

In difficult cases or in situations where intervention to restore blood flow is appropriate, coronary angiography can be performed. A catheter is inserted into an artery (usually the femoral artery) and pushed to the vessels supplying the heart. A radio-opaque dye is administered through the catheter and a sequence of x-rays (fluoroscopy) is performed. Obstructed or narrowed arteries can be identified, and angioplasty applied as a therapeutic measure (see below). Angioplasty requires extensive skill, especially in emergency settings. It is performed by a physician trained in interventional cardiology.

Histopathology

Further information: Timeline of myocardial infarction pathology

Histopathological examination of the heart may reveal infarction at autopsy. Under the microscope, myocardial infarction presents as a circumscribed area of ischemic, coagulative necrosis (cell death). On gross examination, the infarct is not identifiable within the first 12 hours.

Although earlier changes can be discerned using electron microscopy, one of the earliest changes under a normal microscope are so-called wavy fibers. Subsequently, the myocyte cytoplasm becomes more eosinophilic (pink) and the cells lose their transversal striations, with typical changes and eventually loss of the cell nucleus. The interstitium at the margin of the infarcted area is initially infiltrated with neutrophils, then with lymphocytes and macrophages, who phagocytose ("eat") the myocyte debris. The necrotic area is surrounded and progressively invaded by granulation tissue, which will replace the infarct with a fibrous (collagenous) scar (which are typical steps in wound healing). The interstitial space (the space between cells outside of blood vessels) may be infiltrated with red blood cells.

These features can be recognized in cases where the perfusion was not restored; reperfused infarcts can have other hallmarks, such as contraction band necrosis.

First aid

As myocardial infarction is a common medical emergency, the signs are often part of first aid courses. The emergency action principles also apply in the case of myocardial infarction.

Immediate care

When symptoms of myocardial infarction occur, people wait an average of three hours, instead of doing what is recommended: calling for help immediately. Acting immediately by calling the emergency services can prevent sustained damage to the heart ("time is muscle").

Certain positions allow the patient to rest in a position which minimizes breathing difficulties. A half-sitting position with knees bent is often recommended. Access to more oxygen can be given by opening the window and widening the collar for easier breathing.

Aspirin can be given quickly (if the patient is not allergic to aspirin); but taking aspirin before calling the emergency medical services may be associated with unwanted delay. Aspirin has an antiplatelet effect which inhibits formation of further thrombi (blood clots) that clog arteries. Chewing is the preferred method of administration, so that the Aspirin can be absorbed quickly. Dissolved soluble preparations or sublingual administration can also be used. U.S. guidelines recommend a dose of 162–325 mg. Australian guidelines recommend a dose of 150–300 mg.

Glyceryl trinitrate (nitroglycerin) sublingually (under the tongue) can be given if available.

If an automated external defibrillator (AED) is available the rescuer should immediately bring the AED to the patient's side and be prepared to follow its instructions, especially should the victim lose consciousness.

If possible the rescuer should obtain basic information from the victim, in case the patient is unable to answer questions once emergency medical technicians arrive. The victim's name and any information regarding the nature of the victim's pain will be useful to health care providers. The exact time that these symptoms started may be critical for determining what interventions can be safely attempted once the victim reaches the medical center. Other useful pieces of information include what the patient was doing at the onset of symptoms, and anything else that might give clues to the pathology of the chest pain. It is also very important to relay any actions that have been taken, such as the number or dose of aspirin or nitroglycerin given, to the EMS personnel.

Other general first aid principles include monitoring pulse, breathing, level of consciousness and, if possible, the blood pressure of the patient. In case of cardiac arrest, cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) can be administered.

Automatic external defibrillation (AED)

Since the publication of data showing that the availability of automated external defibrillators (AEDs) in public places may significantly increase chances of survival, many of these have been installed in public buildings, public transport facilities, and in non-ambulance emergency vehicles (e.g. police cars and fire engines). AEDs analyze the heart's rhythm and determine whether the rhythm is amenable to defibrillation ("shockable"), as in ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation.

Emergency services

Emergency Medical Services (EMS) Systems vary considerably in their ability to evaluate and treat patients with suspected acute myocardial infarction. Some provide as little as first aid and early defibrillation. Others employ highly trained paramedics with sophisticated technology and advanced protocols. Early access to EMS is promoted by a 9-1-1 system currently available to 90% of the population in the United States. Most are capable of providing oxygen, IV access, sublingual nitroglycerine, morphine, and aspirin. Some are capable of providing thrombolytic therapy in the prehospital setting.

With primary PCI emerging as the preferred therapy for ST segment elevation myocardial infarction, EMS can play a key role in reducing door to balloon intervals (the time from presentation to a hospital ER to the restoration of coronary artery blood flow) by performing a 12 lead ECG in the field and using this information to triage the patient to the most appropriate medical facility. In addition, the 12 lead ECG can be transmitted to the receiving hospital, which enables time saving decisions to be made prior to the patient's arrival. This may include a "cardiac alert" or "STEMI alert" that calls in off duty personnel in areas where the cardiac cath lab is not staffed 24 hours a day. Even in the absence of a formal alerting program, prehospital 12 lead ECGs are independently associated with reduced door to treatment intervals in the emergency department.

Wilderness first aid

In wilderness first aid, a possible heart attack justifies evacuation by the fastest available means, including MEDEVAC, even in the earliest or precursor stages. The patient will rapidly be incapable of further exertion and have to be carried out.

Air travel

Certified personnel traveling by commercial aircraft may be able to assist an MI patient by using the on-board first aid kit, which may contain some cardiac drugs (such as glyceryl trinitrate spray, aspirin, or opioid painkillers), an AED, and oxygen. Pilots may divert the flight to land at a nearby airport. Cardiac monitors are being introduced by some airlines, and they can be used by both on-board and ground-based physicians.

Treatment

A heart attack is a medical emergency which demands both immediate attention and activation of the emergency medical services. The ultimate goal of the management in the acute phase of the disease is to salvage as much myocardium as possible and prevent further complications. As time passes, the risk of damage to the heart muscle increases; hence the phrase that in myocardial infarction, "time is muscle," and time wasted is muscle lost.

The treatments itself may have complications. If attempts to restore the blood flow are initiated after a critical period of only a few hours, the result is reperfusion injury instead of amelioration. Other treatment modalities may also cause complications; the use of antithrombotics for example carries an increased risk of bleeding.

First line

Oxygen, aspirin, glyceryl trinitrate (nitroglycerin) and analgesia (usually morphine, although experts often argue this point), hence the popular mnemonic MONA, morphine, oxygen, nitro, aspirin) are administered as soon as possible. In many areas, first responders can be trained to administer these prior to arrival at the hospital. Morphine is classically the preferred pain relief drug due to its ability to dilate blood vessels, which aids in blood flow to the heart as well as its pain relief properties. However, morphine can also cause hypotension (usually in the setting of hypovolemia), and should be avoided in the case of right ventricular infarction. Moreover, the CRUSADE trial also demonstrated an increase in mortality with administering morphine in the setting of NSTEMI.

Of the first line agents, only aspirin has been proven to decrease mortality.

Once the diagnosis of myocardial infarction is confirmed, other pharmacologic agents are often given. These include beta blockers, anticoagulation (typically with heparin), and possibly additional antiplatelet agents such as clopidogrel. These agents are typically not started until the patient is evaluated by an emergency room physician or under the direction of a cardiologist. These agents can be used regardless of the reperfusion strategy that is to be employed. While these agents can decrease mortality in the setting of an acute myocardial infarction, they can lead to complications and potentially death if used in the wrong setting.

Cocaine associated myocardial infarction should be managed in a manner similar to other patients with acute coronary syndrome except beta blockers should not be used and benzodiazepines should be administered early.

Reperfusion

The concept of reperfusion has become so central to the modern treatment of acute myocardial infarction, that we are said to be in the reperfusion era. Patients who present with suspected acute myocardial infarction and ST segment elevation (STEMI) or new bundle branch block on the 12 lead ECG are presumed to have an occlusive thrombosis in an epicardial coronary artery. They are therefore candidates for immediate reperfusion, either with thrombolytic therapy, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or when these therapies are unsuccessful, bypass surgery.

Individuals without ST segment elevation are presumed to be experiencing either unstable angina (UA) or non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI). They receive many of the same initial therapies and are often stabilized with antiplatelet drugs and anticoagulated. If their condition remains (hemodynamically) stable, they can be offered either late coronary angiography with subsequent restoration of blood flow (revascularization), or non-invasive stress testing to determine if there is significant ischemia that would benefit from revascularization. If hemodynamic instability develops in individuals with NSTEMIs, they may undergo urgent coronary angiography and subsequent revascularization. The use of thrombolytic agents is contraindicated in this patient subset, however.

The basis for this distinction in treatment regimens is that ST segment elevations on an ECG are typically due to complete occlusion of a coronary artery. On the other hand, in NSTEMIs there is typically a sudden narrowing of a coronary artery with preserved (but diminished) flow to the distal myocardium. Anticoagulation and antiplatelet agents are given to prevent the narrowed artery from occluding.

At least 10% of patients with STEMI don't develop myocardial necrosis (as evidenced by a rise in cardiac markers) and subsequent Q waves on EKG after reperfusion therapy. Such a successful restoration of flow to the infarct-related artery during an acute myocardial infarction is known as "aborting" the myocardial infarction. If treated within the hour, about 25% of STEMIs can be aborted.

Thrombolytic therapy

Main article: ThrombolysisThrombolytic therapy is indicated for the treatment of STEMI if the drug can be administered within 12 hours of the onset of symptoms, the patient is eligible based on exclusion criteria, and primary PCI is not immediately available. The effectiveness of thrombolytic therapy is highest in the first 2 hours. After 12 hours, the risk associated with thrombolytic therapy outweighs any benefit. Because irreversible injury occurs within 2–4 hours of the infarction, there is a limited window of time available for reperfusion to work.

Thrombolytic drugs are contraindicated for the treatment of unstable angina and NSTEMI and for the treatment of individuals with evidence of cardiogenic shock.

Although no perfect thrombolytic agent exists, an ideal thrombolytic drug would lead to rapid reperfusion, have a high sustained patency rate, be specific for recent thrombi, be easily and rapidly administered, create a low risk for intra-cerebral and systemic bleeding, have no antigenicity, adverse hemodynamic effects, or clinically significant drug interactions, and be cost effective. Currently available thrombolytic agents include streptokinase, urokinase, and alteplase (recombinant tissue plasminogen activator, rtPA). More recently, thrombolytic agents similar in structure to rtPA such as reteplase and tenecteplase have been used. These newer agents boast efficacy at least as good as rtPA with significantly easier administration. The thrombolytic agent used in a particular individual is based on institution preference and the age of the patient.

Depending on the thrombolytic agent being used, adjuvant anticoagulation with heparin or low molecular weight heparin may be of benefit. With TPa and related agents (reteplase and tenecteplase), heparin is needed to maintain coronary artery patency. Because of the anticoagulant effect of fibrinogen depletion with streptokinase and urokinase treatment, it is less necessary there.

Intracranial bleeding (ICB) and subsequent cerebrovascular accident (CVA) is a serious side effect of thrombolytic use. The risk of ICB is dependent on a number of factors, including a previous episode of intracranial bleed, age of the individual, and the thrombolytic regimen that is being used. In general, the risk of ICB due to thrombolytic use for the treatment of an acute myocardial infarction is between 0.5 and 1 percent.

Thrombolytic therapy to abort a myocardial infarction is not always effective. The degree of effectiveness of a thrombolytic agent is dependent on the time since the myocardial infarction began, with the best results occurring if the thrombolytic agent is used within two hours of the onset of symptoms. If the individual presents more than 12 hours after symptoms commenced, the risk of intracranial bleed are considered higher than the benefits of the thrombolytic agent. Failure rates of thrombolytics can be as high as 20% or higher. In cases of failure of the thrombolytic agent to open the infarct-related coronary artery, the patient is then either treated conservatively with anticoagulants and allowed to "complete the infarction" or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI, see below) is then performed. Percutaneous coronary intervention in this setting is known as "rescue PCI" or "salvage PCI". Complications, particularly bleeding, are significantly higher with rescue PCI than with primary PCI due to the action of the thrombolytic agent.

Percutaneous coronary intervention

Main article: Percutaneous coronary intervention

The benefit of prompt, expertly performed primary percutaneous coronary intervention over thrombolytic therapy for acute ST elevation myocardial infarction is now well established. When performed rapidly by an experienced team, primary PCI restores flow in the culprit artery in more than 95% of patients compared with the spontaneous recanalization rate of about 65%. Logistic and economic obstacles seem to hinder a more widespread application of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) via cardiac catheterization, although the feasibility of regionalized PCI for STEMI is currently being explored in the United States. The use of percutaneous coronary intervention as a therapy to abort a myocardial infarction is known as primary PCI. The goal of primary PCI is to open the artery as soon as possible, and preferably within 90 minutes of the patient presenting to the emergency room. This time is referred to as the door-to-balloon time. Few hospitals can provide PCI within the 90 minute interval, which prompted the American College of Cardiology (ACC) to launch a national Door to Balloon (D2B) Initiative in November 2006. Over 800 hospitals have joined the D2B Alliance as of March 16, 2007.

One particularly successful implementation of a primary PCI protocol is in the Calgary Health Region under the auspices of the Libin Cardiovascular Institute of Alberta. Under this model, EMS teams responding to an emergency electronically transmit the ECG directly to a digital archiving system that allows emergency room physicians and/or cardiologists to immediately confirm the diagnosis. This in turn allows for redirection of the EMS teams to facilities prepped to conduct time-critical angioplasty, based on the ECG analysis. In an article published in the Canadian Medical Association Journal in June 2007, the Calgary implementation resulted in a median time to treatment of 62 minutes.

The current guidelines in the United States restrict primary PCI to hospitals with available emergency bypass surgery as a backup, but this is not the case in other parts of the world.

Primary PCI involves performing a coronary angiogram to determine the anatomical location of the infarcting vessel, followed by balloon angioplasty (and frequently deployment of an intracoronary stent) of the thrombosed arterial segment. In some settings, an extraction catheter may be used to attempt to aspirate (remove) the thrombus prior to balloon angioplasty. While the use of intracoronary stents do not improve the short term outcomes in primary PCI, the use of stents is widespread because of the decreased rates of procedures to treat restenosis compared to balloon angioplasty.

Adjuvant therapy during primary PCI include intravenous heparin, aspirin, and clopidogrel. The use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors are often used in the setting of primary PCI to reduce the risk of ischemic complications during the procedure. Due to the number of antiplatelet agents and anticoagulants used during primary PCI, the risk of bleeding associated with the procedure are higher than during an elective PCI.

Coronary artery bypass surgery

Main article: Coronary artery bypass graft surgery

Despite the guidelines, emergency bypass surgery for the treatment of an acute myocardial infarction (MI) is less common than PCI or medical management. In an analysis of patients in the U.S. National Registry of Myocardial Infarction (NRMI) from January 1995 to May 2004, the percentage of patients with cardiogenic shock treated with primary PCI rose from 27.4% to 54.4%, while the increase in CABG treatment was only from 2.1% to 3.2%.

Emergency coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG) is usually undertaken to simultaneously treat a mechanical complication, such as a ruptured papillary muscle, or a ventricular septal defect, with ensueing cardiogenic shock. In uncomplicated MI, the mortality rate can be high when the surgery is performed immediately following the infarction. If this option is entertained, the patient should be stabilized prior to surgery, with supportive interventions such as the use of an intra-aortic balloon pump. In patients developing cardiogenic shock after a myocardial infarction, both PCI and CABG are satisfactory treatment options, with similar survival rates.

Coronary artery bypass surgery involves an artery or vein from the patient being implanted to bypass narrowings or occlusions on the coronary arteries. Several arteries and veins can be used, however internal mammary artery grafts have demonstrated significantly better long-term patency rates than great saphenous vein grafts. In patients with two or more coronary arteries affected, bypass surgery is associated with higher long-term survival rates compared to percutaneous interventions. In patients with single vessel disease, surgery is comparably safe and effective, and may be a treatment option in selected cases. Bypass surgery has higher costs initially, but becomes cost-effective in the long term. A surgical bypass graft is more invasive initially but bears less risk of recurrent procedures (but these may be again minimally invasive).

Monitoring for arrhythmias

Additional objectives are to prevent life-threatening arrhythmias or conduction disturbances. This requires monitoring in a coronary care unit and protocolised administration of antiarrhythmic agents. Antiarrhythmic agents are typically only given to individuals with life-threatening arrhythmias after a myocardial infarction and not to suppress the ventricular ectopy that is often seen after a myocardial infarction.

Rehabilitation

Cardiac rehabilitation aims to optimize function and quality of life in those afflicted with a heart disease. This can be with the help of a physician, or in the form of a cardiac rehabilitation program.

Physical exercise is an important part of rehabilitation after a myocardial infarction, with beneficial effects on cholesterol levels, blood pressure, weight, stress and mood. Some patients become afraid of exercising because it might trigger another infarct. Patients are stimulated to exercise, and should only avoid certain exerting activities such as shovelling. Local authorities may place limitations on driving motorised vehicles. Some people are afraid to have sex after a heart attack. Most people can resume sexual activities after 3 to 4 weeks. The amount of activity needs to be dosed to the patient's possibilities.

Secondary prevention

The risk of a recurrent myocardial infarction decreases with strict blood pressure management and lifestyle changes, chiefly smoking cessation, regular exercise, a sensible diet for patients with heart disease, and limitation of alcohol intake.

Patients are usually commenced on several long-term medications post-MI, with the aim of preventing secondary cardiovascular events such as further myocardial infarctions, congestive heart failure or cerebrovascular accident (CVA). Unless contraindicated, such medications may include:

- Antiplatelet drug therapy such as aspirin and/or clopidogrel should be continued to reduce the risk of plaque rupture and recurrent myocardial infarction. Aspirin is first-line, owing to its low cost and comparable efficacy, with clopidogrel reserved for patients intolerant of aspirin. The combination of clopidogrel and aspirin may further reduce risk of cardiovascular events, however the risk of hemorrhage is increased.

- Beta blocker therapy such as metoprolol or carvedilol should be commenced. These have been particularly beneficial in high-risk patients such as those with left ventricular dysfunction and/or continuing cardiac ischaemia. β-Blockers decrease mortality and morbidity. They also improve symptoms of cardiac ischemia in NSTEMI.

- ACE inhibitor therapy should be commenced 24–48 hours post-MI in hemodynamically-stable patients, particularly in patients with a history of MI, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, anterior location of infarct (as assessed by ECG), and/or evidence of left ventricular dysfunction. ACE inhibitors reduce mortality, the development of heart failure, and decrease ventricular remodelling post-MI.

- Statin therapy has been shown to reduce mortality and morbidity post-MI. The effects of statins may be more than their LDL lowering effects. The general consensus is that statins have plaque stabilization and multiple other ("pleiotropic") effects that may prevent myocardial infarction in addition to their effects on blood lipids.

- The aldosterone antagonist agent eplerenone has been shown to further reduce risk of cardiovascular death post-MI in patients with heart failure and left ventricular dysfunction, when used in conjunction with standard therapies above.

- Omega-3 fatty acids, commonly found in fish, have been shown to reduce mortality post-MI. While the mechanism by which these fatty acids decrease mortality is unknown, it has been postulated that the survival benefit is due to electrical stabilization and the prevention of ventricular fibrillation. However, further studies in a high-risk subset have not shown a clear-cut decrease in potentially fatal arrhythmias due to omega-3 fatty acids.

New therapies under investigation

Patients who receive stem cell treatment by coronary artery injections of stem cells derived from their own bone marrow after a myocardial infarction (MI) show improvements in left ventricular ejection fraction and end-diastolic volume not seen with placebo. The larger the initial infarct size, the greater the effect of the infusion. Clinical trials of progenitor cell infusion as a treatment approach to ST elevation MI are proceeding.

There are currently 3 biomaterial and tissue engineering approaches for the treatment of MI, but these are in an even earlier stage of medical research, so many questions and issues need to be addressed before they can be applied to patients. The first involves polymeric left ventricular restraints in the prevention of heart failure. The second utilizes in vitro engineered cardiac tissue, which is subsequently implanted in vivo. The final approach entails injecting cells and/or a scaffold into the myocardium to create in situ engineered cardiac tissue.

Complications

Complications may occur immediately following the heart attack (in the acute phase), or may need time to develop (a chronic problem). After an infarction, an obvious complication is a second infarction, which may occur in the domain of another atherosclerotic coronary artery, or in the same zone if there are any live cells left in the infarct.

Congestive heart failure

Main article: Congestive heart failureA myocardial infarction may compromise the function of the heart as a pump for the circulation, a state called heart failure. There are different types of heart failure; left- or right-sided (or bilateral) heart failure may occur depending on the affected part of the heart, and it is a low-output type of failure. If one of the heart valves is affected, this may cause dysfunction, such as mitral regurgitation in the case of left-sided coronary occlusion that disrupts the blood supply of the papillary muscles. The incidence of heart failure is particularly high in patients with diabetes and requires special management strategies.

Myocardial rupture

Main article: Myocardial ruptureMyocardial rupture is most common three to five days after myocardial infarction, commonly of small degree, but may occur one day to three weeks later. In the modern era of early revascularization and intensive pharmacotherapy as treatment for MI, the incidence of myocardial rupture is about 1% of all MIs. This may occur in the free walls of the ventricles, the septum between them, the papillary muscles, or less commonly the atria. Rupture occurs because of increased pressure against the weakened walls of the heart chambers due to heart muscle that cannot pump blood out effectively. The weakness may also lead to ventricular aneurysm, a localized dilation or ballooning of the heart chamber.

Risk factors for myocardial rupture include completion of infarction (no revascularization performed), female sex, advanced age, and a lack of a previous history of myocardial infarction. In addition, the risk of rupture is higher in individuals who are revascularized with a thrombolytic agent than with PCI. The shear stress between the infarcted segment and the surrounding normal myocardium (which may be hypercontractile in the post-infarction period) makes it a nidus for rupture.

Rupture is usually a catastrophic event that may result a life-threatening process known as cardiac tamponade, in which blood accumulates within the pericardium or heart sac, and compresses the heart to the point where it cannot pump effectively. Rupture of the intraventricular septum (the muscle separating the left and right ventricles) causes a ventricular septal defect with shunting of blood through the defect from the left side of the heart to the right side of the heart, which can lead to right ventricular failure as well as pulmonary overcirculation. Rupture of the papillary muscle may also lead to acute mitral regurgitation and subsequent pulmonary edema and possibly even cardiogenic shock.

Life-threatening arrhythmia

Since the electrical characteristics of the infarcted tissue change (see pathophysiology section), arrhythmias are a frequent complication. The re-entry phenomenon may cause rapid heart rates (ventricular tachycardia and even ventricular fibrillation), and ischemia in the electrical conduction system of the heart may cause a complete heart block (when the impulse from the sinoatrial node, the normal cardiac pacemaker, does not reach the heart chambers).

Pericarditis

Main article: PericarditisAs a reaction to the damage of the heart muscle, inflammatory cells are attracted. The inflammation may reach out and affect the heart sac. This is called pericarditis. In Dressler's syndrome, this occurs several weeks after the initial event.

Cardiogenic shock

A complication that may occur in the acute setting soon after a myocardial infarction or in the weeks following it is cardiogenic shock. Cardiogenic shock is defined as a hemodynamic state in which the heart cannot produce enough of a cardiac output to supply an adequate amount of oxygenated blood to the tissues of the body.

While the data on performing interventions on individuals with cardiogenic shock is sparse, trial data suggests a long-term mortality benefit in undergoing revascularization if the individual is less than 75 years old and if the onset of the acute myocardial infarction is less than 36 hours and the onset of cardiogenic shock is less than 18 hours. If the patient with cardiogenic shock is not going to be revascularized, aggressive hemodynamic support is warranted, with insertion of an intra-aortic balloon pump if not contraindicated. If diagnostic coronary angiography does not reveal a culprit blockage that is the cause of the cardiogenic shock, the prognosis is poor.

Prognosis

The prognosis for patients with myocardial infarction varies greatly, depending on the patient, the condition itself and the given treatment. Using simple variables which are immediately available in the emergency room, patients with a higher risk of adverse outcome can be identified. For example, one study found that 0.4% of patients with a low risk profile had died after 90 days, whereas the mortality rate in high risk patients was 21.1%.

Although studies differ in the identified variables, some of the more reproduced risk stratifiers include age, hemodynamic parameters (such as heart failure, cardiac arrest on admission, systolic blood pressure, or Killip class of two or greater), ST-segment deviation, diabetes, serum creatinine concentration, peripheral vascular disease and elevation of cardiac markers.

Assessment of left ventricular ejection fraction may increase the predictive power of some risk stratification models. The prognostic importance of Q-waves is debated. Prognosis is significantly worsened if a mechanical complication (papillary muscle rupture, myocardial free wall rupture, and so on) were to occur.

There is evidence that case fatality of myocardial infarction has been improving over the years in all ethnicities.

Legal implications

At common law, a myocardial infarction is generally a disease, but may sometimes be an injury. This has implications for no-fault insurance schemes such as workers' compensation. A heart attack is generally not covered; however, it may be a work-related injury if it results, for example, from unusual emotional stress or unusual exertion. Additionally, in some jurisdictions, heart attacks suffered by persons in particular occupations such as police officers may be classified as line-of-duty injuries by statute or policy. In some countries or states, a person who has suffered from a myocardial infarction may be prevented from participating in activity that puts other people's lives at risk, for example driving a car, taxi or airplane.

See also

- Acute coronary syndrome

- Angina

- Cardiac arrest

- Coronary thrombosis

- Hibernating myocardium

- Stunned myocardium

- Ventricular remodeling

References

- Kosuge, M (March 2006). "Differences between men and women in terms of clinical features of ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction". Circulation Journal. 70 (3): 222–226. doi:10.1253/circj.70.222. PMID 16501283. Retrieved 2008-05-31.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ The World Health Report 2004 - Changing History (PDF). World Health Organization. 2004. pp. 120–4. ISBN 92-4-156265-X.

{{cite book}}: External link in|authorlink= - Bax L, Algra A, Mali WP, Edlinger M, Beutler JJ, van der Graaf Y (2008). "Renal function as a risk indicator for cardiovascular events in 3216 patients with manifest arterial disease". Atherosclerosis. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.12.006. PMID 18241872.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Pearte CA, Furberg CD, O'Meara ES; et al. (2006). "Characteristics and baseline clinical predictors of future fatal versus nonfatal coronary heart disease events in older adults: the Cardiovascular Health Study". Circulation. 113 (18): 2177–85. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.610352. PMID 16651468.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Erhardt L, Herlitz J, Bossaert L; et al. (2002). "Task force on the management of chest pain" (PDF). Eur. Heart J. 23 (15): 1153–76. doi:10.1053/euhj.2002.3194. PMID 12206127.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Cause of Death - UC Atlas of Global Inequality". Center for Global, International and Regional Studies (CGIRS) at the University of California Santa Cruz. Retrieved December 7 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - "Deaths and percentage of total death for the 10 leading causes of death: United States, 2002-2003" (PDF). National Center of Health Statistics. Retrieved April 17 2007.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - "Heart Attack and Angina Statistics". American Heart Association. 2003. Retrieved December 7 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - Mukherjee AK. (1995). "Prediction of coronary heart disease using risk factor categories". J Indian Med Assoc. PMID 8713248.

- Ghaffar A, Reddy KS and Singhi M (2004). "Burden of non-communicable diseases in South Asia" (PDF). BMJ. 328: 807–810. doi:10.1136/bmj.328.7443.807. PMID 15070638.

- ^ Rastogi T, Vaz M, Spiegelman D, Reddy KS, Bharathi AV, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC and Ascherio1 A (2004). "Physical activity and risk of coronary heart disease in India" (PDF). Int. J. Epidemiol. 33: 1–9. doi:10.1093/ije/dyh042. PMID 15044412.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Gupta R. (2007). "Escalating Coronary Heart Disease and Risk Factors in South Asians" (PDF). Indian Heart Journal: 214–17.

- Gupta R, Misra A, Pais P, Rastogi P and Gupta VP. (2006). "Correlation of regional cardiovascular disease mortality in India with lifestyle and nutritional factors" (PDF). International Journal of Cardiology. 108 (3): 291–300. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2005.05.044.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wilson PW, D'Agostino RB, Levy D, Belanger AM, Silbershatz H, Kannel WB. (1998). "Prediction of coronary heart disease using risk factor categories" (PDF). Circulation. 97 (18): 1837–47. PMID 9603539.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Cite error: The named reference "Framingham1998" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, Bautista L, Franzosi MG, Commerford P, Lang CC, Rumboldt Z, Onen CL, Lisheng L, Tanomsup S, Wangai P Jr, Razak F, Sharma AM, Anand SS; INTERHEART Study Investigators. (2005). "Obesity and the risk of myocardial infarction in 27,000 participants from 52 countries: a case-control study". Lancet. 366 (9497): 1640–9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67663-5. PMID 16271645.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Jensen G, Nyboe J, Appleyard M, Schnohr P. (1991). "Risk factors for acute myocardial infarction in Copenhagen, II: Smoking, alcohol intake, physical activity, obesity, oral contraception, diabetes, lipids, and blood pressure". Eur Heart J. 12 (3): 298–308. PMID 2040311.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Nyboe J, Jensen G, Appleyard M, Schnohr P. (1989). "Risk factors for acute myocardial infarction in Copenhagen. I: Hereditary, educational and socioeconomic factors. Copenhagen City Heart Study". Eur Heart J. 10 (10): 910–6. PMID 2598948.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Khader YS, Rice J, John L, Abueita O. (2003). "Oral contraceptives use and the risk of myocardial infarction: a meta-analysis". Contraception. 68 (1): 11–7. doi:10.1016/S0010-7824(03)00073-8. PMID 12878281.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wilson AM, Ryan MC, Boyle AJ. (2006). "The novel role of C-reactive protein in cardiovascular disease: risk marker or pathogen". Int J Cardiol. 106 (3): 291–7. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2005.01.068. PMID 16337036.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Pearson TA, Mensah GA, Alexander RW, Anderson JL, Cannon RO 3rd, Criqui M, Fadl YY, Fortmann SP, Hong Y, Myers GL, Rifai N, Smith SC Jr, Taubert K, Tracy RP, Vinicor F; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; American Heart Association. (2003). "Markers of inflammation and cardiovascular disease: application to clinical and public health practice: A statement for healthcare professionals from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Heart Association" (PDF). Circulation. 107 (3): 499–511. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000052939.59093.45. PMID 12551878.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Janket SJ, Baird AE, Chuang SK, Jones JA. (2003). "Meta-analysis of periodontal disease and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke". Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 95 (5): 559–69. doi:10.1038/sj.ebd.6400272. PMID 12738947.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Pihlstrom BL, Michalowicz BS, Johnson NW. (2005). "Periodontal diseases". Lancet. 366 (9499): 1809–20. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67728-8. PMID 16298220.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Scannapieco FA, Bush RB, Paju S. (2003). "Associations between periodontal disease and risk for atherosclerosis, cardiovascular disease, and stroke. A systematic review". Ann Periodontol. 8 (1): 38–53. doi:10.1902/annals.2003.8.1.38. PMID 14971247.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - D'Aiuto F, Parkar M, Nibali L, Suvan J, Lessem J, Tonetti MS. (2006). "Periodontal infections cause changes in traditional and novel cardiovascular risk factors: results from a randomized controlled clinical trial". Am Heart J. 151 (5): 977–84. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2005.06.018. PMID 16644317.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Lourbakos A, Yuan YP, Jenkins AL, Travis J, Andrade-Gordon P, Santulli R, Potempa J, Pike RN. (2001). "Activation of protease-activated receptors by gingipains from Porphyromonas gingivalis leads to platelet aggregation: a new trait in microbial pathogenicity" (PDF). Blood. 97 (12): 3790–7. doi:10.1182/blood.V97.12.3790. PMID 11389018.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Qi M, Miyakawa H, Kuramitsu HK. (2003). "Porphyromonas gingivalis induces murine macrophage foam cell formation". Microb Pathog. 35 (6): 259–67. doi:10.1016/j.micpath.2003.07.002. PMID 14580389.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Spahr A, Klein E, Khuseyinova N, Boeckh C, Muche R, Kunze M, Rothenbacher D, Pezeshki G, Hoffmeister A, Koenig W. (2006). "Periodontal infections and coronary heart disease: role of periodontal bacteria and importance of total pathogen burden in the Coronary Event and Periodontal Disease (CORODONT) study". Arch Intern Med. 166 (5): 554–9. doi:10.1001/archinte.166.5.554. PMID 16534043.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Davis TM, Balme M, Jackson D, Stuccio G, Bruce DG (2000). "The diagonal ear lobe crease (Frank's sign) is not associated with coronary artery disease or retinopathy in type 2 diabetes: the Fremantle Diabetes Study". Aust N Z J Med. 30 (5): 573–7. PMID 11108067.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Lichstein E, Chadda KD, Naik D, Gupta PK. (1974). "Diagonal ear-lobe crease: prevalence and implications as a coronary risk factor". N Engl J Med. 290 (11): 615–6. PMID 4812503.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Miric D, Fabijanic D, Giunio L, Eterovic D, Culic V, Bozic I, Hozo I. (1998). "Dermatological indicators of coronary risk: a case-control study". Int J Cardiol. 67 (3): 251–5. doi:10.1016/S0167-5273(98)00313-1. PMID 9894707.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Greenland P, LaBree L, Azen SP, Doherty TM, Detrano RC (2004). "Coronary artery calcium score combined with Framingham score for risk prediction in asymptomatic individuals". JAMA. 291 (2): 210–5. doi:10.1001/jama.291.2.210. PMID 14722147.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Detrano R, Guerci AD, Carr JJ; et al. (2008). "Coronary calcium as a predictor of coronary events in four racial or ethnic groups". N. Engl. J. Med. 358 (13): 1336–45. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa072100. PMID 18367736.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Arad Y, Goodman KJ, Roth M, Newstein D, Guerci AD (2005). "Coronary calcification, coronary disease risk factors, C-reactive protein, and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease events: the St. Francis Heart Study". J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 46 (1): 158–65. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2005.02.088. PMID 15992651.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Krijnen PA, Nijmeijer R, Meijer CJ, Visser CA, Hack CE, Niessen HW. (2002). "Apoptosis in myocardial ischaemia and infarction". J Clin Pathol. 55 (11): 801–11. doi:10.1136/jcp.55.11.801. PMID 12401816.