| Revision as of 01:07, 25 February 2009 view source71.113.5.72 (talk) →Events following reductions in vaccination← Previous edit | Revision as of 01:22, 25 February 2009 view source Zodon (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users13,210 edits Undid revision 273090487 by 71.113.5.72 (talk) rv unexplained deletion of sourced materialNext edit → | ||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

| ===Cost-effectiveness=== | ===Cost-effectiveness=== | ||

| Commonly-used vaccines are a cost-effective and preventive way of promoting health, compared to the treatment of acute or chronic disease. In the U.S. during the year 2001, routine childhood immunizations against seven diseases were estimated to save over $40 billion per birth-year cohort in overall social costs including $10 billion in direct ], and the societal benefit-cost ratio for these vaccinations was estimated to be 16.5.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Zhou F, Santoli J, Messonnier ML ''et al.'' |title=Economic evaluation of the 7-vaccine routine childhood immunization schedule in the United States, 2001 |journal=Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med |volume=159 |issue=12 |pages=1136–44 |year=2005 |pmid=16330737 |url=http://archpedi.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/full/159/12/1136 |doi=10.1001/archpedi.159.12.1136}}</ref> | Commonly-used vaccines are a cost-effective and preventive way of promoting health, compared to the treatment of acute or chronic disease. In the U.S. during the year 2001, routine childhood immunizations against seven diseases were estimated to save over $40 billion per birth-year cohort in overall social costs including $10 billion in direct ], and the societal benefit-cost ratio for these vaccinations was estimated to be 16.5.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Zhou F, Santoli J, Messonnier ML ''et al.'' |title=Economic evaluation of the 7-vaccine routine childhood immunization schedule in the United States, 2001 |journal=Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med |volume=159 |issue=12 |pages=1136–44 |year=2005 |pmid=16330737 |url=http://archpedi.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/full/159/12/1136 |doi=10.1001/archpedi.159.12.1136}}</ref> | ||

| ===Events following reductions in vaccination=== | |||

| In several countries, reductions in the use of some vaccines were followed by increases in the diseases' morbidity and mortality.<ref name=Gangarosa_pertussis /><ref name=Allen_herd /> According to the ], continued high levels of vaccine coverage are necessary to prevent resurgence of diseases which have been nearly eliminated.<ref name='CDC_stop'> {{cite web|url=http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vac-gen/whatifstop.htm |title=What would happen if we stopped vaccinations? |accessdate=2008-04-25 |date=2007-06-12 |publisher=] }}</ref> | |||

| ;Stockholm, smallpox (1873–74) | |||

| An anti-vaccination campaign motivated by religious objections, by concerns about effectiveness, and by concerns about individual rights, led to the vaccination rate in Stockholm dropping to just over 40%, compared to about 90% elsewhere in Sweden. A major smallpox epidemic then started in 1873. It led to a rise in vaccine uptake and an end of the epidemic.<ref>{{cite journal |journal= Soc Hist Med |year=1992 |volume=5 |issue=3 |pages=369–88 |title= The right to die? Anti-vaccination activity and the 1874 smallpox epidemic in Stockholm |author= Nelson MC, Rogers J |pmid=11645870 |doi= 10.1093/shm/5.3.369}}</ref> | |||

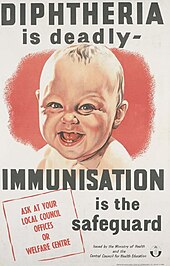

| ] urged British residents to immunize children against diphtheria.]] | |||

| ;UK, DPT (1970s–80s) | |||

| A 1974 report ascribed 36 reactions to ] (pertussis) vaccine, a prominent public-health academic claimed that the vaccine was only marginally effective and questioned whether its benefits outweigh its risks, and extended television and press coverage caused a scare. Vaccine uptake in the UK decreased from 81% to 31% and pertussis epidemics followed, leading to deaths of some children. Mainstream medical opinion continued to support the effectiveness and safety of the vaccine; public confidence was restored after the publication of a national reassessment of vaccine efficacy. Vaccine uptake then increased to levels above 90% and disease incidence declined dramatically.<ref name=Gangarosa_pertussis>{{cite journal |journal=Lancet |year=1998 |volume=351 |issue=9099 |pages=356–61 |title= Impact of anti-vaccine movements on pertussis control: the untold story |author= Gangarosa EJ, Galazka AM, Wolfe CR ''et al.'' |doi=10.1016/S0140-6736(97)04334-1 |pmid=9652634}}</ref> | |||

| ;Sweden, pertussis (1979–96) | |||

| In the vaccination moratorium period that occurred when ] suspended vaccination against whooping cough (pertussis) from 1979 to 1996, 60% of the country's children contracted the potentially fatal disease before the age of ten years; close medical monitoring kept the death rate from whooping cough at about one per year.<ref name=Allen_herd>{{cite journal |author= Allen A |title=Bucking the herd |journal= The Atlantic |year=2002 |volume=290 |issue=2 |pages=40–2 |url=http://immunize.org/exemptions/allen.htm |accessdate=2007-11-07}}</ref> Pertussis continues to be a major health problem in developing countries, where mass vaccination is not practiced; the World Health Organization estimates it caused 294,000 deaths in 2002.<ref>{{cite book |chapter=Pertussis |title= Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases |editor= Atkinson W, Hamborsky J, McIntyre L, Wolfe S |author= Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |location= Washington, DC |publisher= Public Health Foundation |year=2007 |chapterurl=http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/downloads/pert.pdf}}</ref> | |||

| ;Netherlands, measles (1999–2000) | |||

| <!-- I'm uncertain whether religious behaviour is in the same category - this is more like a control experiment (as sometimes demanded by anti-vaccinationists) If we define a-v as actively trying to stop others being vaccinated this group probably fall outside it, and therefore should move to the vaccination article AKM --> | |||

| An outbreak at a religious community and school in ] illustrates the effect of measles in an unvaccinated population.<ref>{{cite journal |title= Measles outbreak—Netherlands, April 1999–January 2000 | url=http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm4914a2.htm | journal= MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep |author= Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |year=2000 | volume=49 | issue=14 | pages=299–303 |pmid=10825086}}</ref> The population in the several provinces affected had a high level of immunization with the exception of ] who traditionally do not accept vaccination. The three measles-related deaths and 68 hospitalizations that occurred among 2961 cases in the Netherlands demonstrate that measles can be severe and may result in death even in industrialized countries. | |||

| ;UK and Ireland, measles (2000) | |||

| As a result of the ] vaccination compliance dropped sharply in the United Kingdom after 1996.<ref name=Pepys>{{cite journal |journal=Clin Med |year=2007 |volume=7 |issue=6 |pages=562–78 |title= Science and serendipity |author= Pepys MB |pmid=18193704}}</ref> From late 1999 until the summer of 2000, there was a measles outbreak in ], Ireland. At the time, the national immunization level had fallen below 80%, and in part of North Dublin the level was around 60%. There were more than 100 hospital admissions from over 300 cases. Three children died and several more were gravely ill, some requiring mechanical ventilation to recover.<ref name="ireland_measles_2000">{{cite news|title=Measles outbreak feared |date=], ] |publisher= BBC News |url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/health/769381.stm |accessdate=2007-11-23}}</ref><ref name="bbc_measles_outbreak">{{cite journal | author = McBrien J, Murphy J, Gill D, Cronin M, O'Donovan C, Cafferkey M | title = Measles outbreak in Dublin, 2000 | journal = Pediatr Infect Dis J | volume = 22 | issue = 7 | pages = 580–4 | year = 2003 | pmid = 12867830 | doi = 10.1097/00006454-200307000-00002}}</ref> | |||

| ;Nigeria, polio, measles, diphtheria (2001 onward) | |||

| In the early 2000s, conservative religious leaders in northern ], suspicious of ], advised their followers to not have their children vaccinated with oral polio vaccine. The boycott was endorsed by the governor of ], and immunization was suspended for several months. Subsequently, polio reappeared in a dozen formerly polio-free neighbors of Nigeria, and genetic tests showed the virus was the same one that originated in northern Nigeria: Nigeria had become a net exporter of polio virus to its African neighbors. People in the northern states were also reported to be wary of other vaccinations, and Nigeria reported over 20,000 measles cases and nearly 600 deaths from measles from January through March 2005.<ref name=Clements>{{cite journal |journal= Curr Drug Saf |volume=1 |issue=1 |year=2006 |pages=117–9 |title= How vaccine safety can become political – the example of polio in Nigeria |author= Clements CJ, Greenough P, Schull D |url=http://bentham.org/cds/samples/cds1-1/Clements.pdf |format=PDF |doi= 10.2174/157488606775252575}}</ref> In 2006 Nigeria accounted for over half of all new polio cases worldwide.<ref>{{cite web |title= Wild poliovirus 2000–2008 |date=2008-02-05 |url=http://www.polioeradication.org/content/general/casecount.pdf |format=PDF |publisher= Global Polio Eradication Initiative |accessdate=2008-02-11}}</ref> Outbreaks continued thereafter; for example, at least 200 children died in a late-2007 measles outbreak in ].<ref>{{cite news |title= 'Hundreds' dead in measles outbreak |publisher=IRIN |date=2007-12-14 |url=http://irinnews.org/Report.aspx?ReportId=75883 |accessdate=2008-02-10}}</ref> | |||

| ;Indiana, USA, measles (2005) | |||

| A 2005 measles outbreak in the US state of ] was attributed to parents who had refused to have their children vaccinated.<ref name=parker>{{cite journal |author=Parker A, Staggs W, Dayan G ''et al.'' |title= Implications of a 2005 measles outbreak in Indiana for sustained elimination of measles in the United States |journal= N Engl J Med |volume=355 |issue=5 |pages=447–55 |year=2006 |pmid=16885548 |doi= 10.1056/NEJMoa060775}}</ref> Most cases of pediatric ] in the U.S. occur in children whose parents objected to their vaccination.<ref>{{cite journal |author= Fair E, Murphy TV, Golaz A, Wharton M |title= Philosophic objection to vaccination as a risk for tetanus among children younger than 15 years |journal=Pediatrics |volume=109 |issue=1 |pages=e2 |year=2002 |pmid=11773570 |url=http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/cgi/content/full/109/1/e2 |doi= 10.1542/peds.109.1.e2}}</ref> | |||

| ==Safety== | ==Safety== | ||

Revision as of 01:22, 25 February 2009

A vaccine controversy is a dispute over the morality, ethics, effectiveness, or safety of vaccination. Medical opinion is that the benefits of preventing suffering and death from infectious diseases outweigh rare adverse effects of immunization. Since vaccination began in the late 18th century, opponents have argued that vaccines do not work, that they are or may be dangerous, that individuals should rely on personal hygiene instead, or that mandatory vaccinations violate individual rights or religious principles.

Effectiveness

Mass vaccination helped eradicate smallpox, which once killed as many as every seventh child in Europe,. It almost eradicated polio. As a more modest example, incidence of invasive disease with Haemophilus influenzae, a major cause of bacterial meningitis and other serious disease in children, has decreased by over 99% in the U.S. since the introduction of a vaccine in 1988. Fully vaccinating all U.S. children born in a given year from birth to adolescence saves an estimated 33,000 lives and prevents an estimated 14 million infections.

Some vaccine critics claim that there have never been any benefits to public health from vaccination. They argue that all the reduction of communicable diseases which were rampant in conditions where overcrowding, poor sanitation, almost non-existent hygiene and a yearly period of very restricted diet existed, are reduced because of changes in conditions excepting vaccination. Other critics argue that immunity given by vaccines is only temporary and requires boosters, whereas those who survive the disease become permanently immune. As discussed below, the philosophies of some alternative medicine practitioners are incompatible with the idea that vaccines are effective.

Children who survive diseases such as diphtheria develop a natural immunity that lasts longer than immunity developed via vaccination. Even though the overall mortality rate is much lower with vaccination, the percentage of adults protected against the disease may also be lower. Vaccination critics argue that for diseases like diphtheria the extra risk to older or weaker adults may outweigh the benefit of lowering the mortality rate among the general population.

Population health

Lack of complete vaccine coverage increases the risk of disease for the entire population, including those who have been vaccinated. One study found that doubling the number of unvaccinated individuals would increase the risk of measles in vaccinated children anywhere from 5–30%. A second study provided evidence that the risk of measles and pertussis increased in vaccinated children proportionally to the number of unvaccinated individuals among them, again highlighting the evident efficacy of widespread vaccine coverage for public health.

Cost-effectiveness

Commonly-used vaccines are a cost-effective and preventive way of promoting health, compared to the treatment of acute or chronic disease. In the U.S. during the year 2001, routine childhood immunizations against seven diseases were estimated to save over $40 billion per birth-year cohort in overall social costs including $10 billion in direct health costs, and the societal benefit-cost ratio for these vaccinations was estimated to be 16.5.

Events following reductions in vaccination

In several countries, reductions in the use of some vaccines were followed by increases in the diseases' morbidity and mortality. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, continued high levels of vaccine coverage are necessary to prevent resurgence of diseases which have been nearly eliminated.

- Stockholm, smallpox (1873–74)

An anti-vaccination campaign motivated by religious objections, by concerns about effectiveness, and by concerns about individual rights, led to the vaccination rate in Stockholm dropping to just over 40%, compared to about 90% elsewhere in Sweden. A major smallpox epidemic then started in 1873. It led to a rise in vaccine uptake and an end of the epidemic.

- UK, DPT (1970s–80s)

A 1974 report ascribed 36 reactions to whooping cough (pertussis) vaccine, a prominent public-health academic claimed that the vaccine was only marginally effective and questioned whether its benefits outweigh its risks, and extended television and press coverage caused a scare. Vaccine uptake in the UK decreased from 81% to 31% and pertussis epidemics followed, leading to deaths of some children. Mainstream medical opinion continued to support the effectiveness and safety of the vaccine; public confidence was restored after the publication of a national reassessment of vaccine efficacy. Vaccine uptake then increased to levels above 90% and disease incidence declined dramatically.

- Sweden, pertussis (1979–96)

In the vaccination moratorium period that occurred when Sweden suspended vaccination against whooping cough (pertussis) from 1979 to 1996, 60% of the country's children contracted the potentially fatal disease before the age of ten years; close medical monitoring kept the death rate from whooping cough at about one per year. Pertussis continues to be a major health problem in developing countries, where mass vaccination is not practiced; the World Health Organization estimates it caused 294,000 deaths in 2002.

- Netherlands, measles (1999–2000)

An outbreak at a religious community and school in The Netherlands illustrates the effect of measles in an unvaccinated population. The population in the several provinces affected had a high level of immunization with the exception of one of the religious denominations who traditionally do not accept vaccination. The three measles-related deaths and 68 hospitalizations that occurred among 2961 cases in the Netherlands demonstrate that measles can be severe and may result in death even in industrialized countries.

- UK and Ireland, measles (2000)

As a result of the MMR vaccine controversy vaccination compliance dropped sharply in the United Kingdom after 1996. From late 1999 until the summer of 2000, there was a measles outbreak in North Dublin, Ireland. At the time, the national immunization level had fallen below 80%, and in part of North Dublin the level was around 60%. There were more than 100 hospital admissions from over 300 cases. Three children died and several more were gravely ill, some requiring mechanical ventilation to recover.

- Nigeria, polio, measles, diphtheria (2001 onward)

In the early 2000s, conservative religious leaders in northern Nigeria, suspicious of Western medicine, advised their followers to not have their children vaccinated with oral polio vaccine. The boycott was endorsed by the governor of Kano State, and immunization was suspended for several months. Subsequently, polio reappeared in a dozen formerly polio-free neighbors of Nigeria, and genetic tests showed the virus was the same one that originated in northern Nigeria: Nigeria had become a net exporter of polio virus to its African neighbors. People in the northern states were also reported to be wary of other vaccinations, and Nigeria reported over 20,000 measles cases and nearly 600 deaths from measles from January through March 2005. In 2006 Nigeria accounted for over half of all new polio cases worldwide. Outbreaks continued thereafter; for example, at least 200 children died in a late-2007 measles outbreak in Borno State.

- Indiana, USA, measles (2005)

A 2005 measles outbreak in the US state of Indiana was attributed to parents who had refused to have their children vaccinated. Most cases of pediatric tetanus in the U.S. occur in children whose parents objected to their vaccination.

Safety

Few deny the vast improvements vaccination has made to public health; a more common concern is their safety. All vaccines may cause side effects, and immunization safety is a real concern. Controversies in this area revolve around the question of whether the risks of perceived adverse events following immunization outweigh the benefits of preventing adverse effects of common diseases.

Vaccine overload

Vaccine overload is the theory that giving many vaccines at once may overwhelm or weaken a child's immune system, and lead to autism or other adverse effects. Although no scientific evidence supports this theory, it has caused many parents to delay or avoid immunizing their children.

The theory has several flaws. Vaccinated children are no more susceptible than are unvaccinated children to infections not prevented by vaccines. Unlike autoimmune diseases like multiple sclerosis, in autism there is no evidence of harm to the immune systems in the central nervous systems of people with autism. A combination of vaccines induces an immune response comparable in size to when the vaccines are given individually. Common childhood conditions such as fevers and middle ear infections pose a much greater challenge to the immune system than vaccines do. Because of changes in vaccine formulation, the fourteen vaccines now given to young U.S. children contain less than 10% of the number of immunologic components of the seven vaccines given in 1980.

It would be hard to study scientifically whether autism is less common in children who do not follow recommended vaccination schedules, due to the ethics of basing experiments on withholding vaccines from children, and due to the likely differences in health care seeking behaviors of undervaccinated children.

Thiomersal

Main article: Thiomersal controversyThe organic mercury content of thiomersal in child vaccines has been alleged to contribute to autism, and thousands of parents in the United States have pursued legal compensation from a federal fund.

In July 1999, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) asked vaccine makers to remove thiomersal from vaccines as quickly as possible, and thiomersal has been phased out of most U.S. and European vaccines. However, the 2004 Institute of Medicine (IOM) panel favoured rejecting any causal relationship between thiomersal-containing vaccines and autism. The CDC and the AAP followed the precautionary principle, which assumes that there is no harm in exercising caution even if it later turns out to be unwarranted, but their 1999 action sparked confusion and controversy that has diverted attention and resources away from efforts to determine the causes of autism. The current scientific consensus is that there is no convincing scientific evidence that thiomersal causes or helps cause autism.

MMR vaccine

Main article: MMR vaccine controversyIn the UK, the MMR vaccine was the subject of controversy after publication of a 1998 paper by Andrew Wakefield, et al., reporting a study of 12 children mostly with autism spectrum disorders with onset soon after administration of the vaccine. During a 1998 press conference, Wakefield suggested that giving children the vaccines in three separate doses would be safer than a single vaccination. This suggestion was not supported by the paper, and several subsequent peer-reviewed studies have failed to show any association between the vaccine and autism. Wakefield has been heavily criticized on scientific grounds and for triggering a decline in vaccination rates, as well as on ethical grounds for the way the research was conducted. In 2009 The Sunday Times reported that Wakefield had manipulated patient data and misreported results in his 1998 paper, creating the appearance of a link with autism.

In 2004 the MMR-and-autism interpretation of the paper was formally retracted by 10 of Wakefield's 12 co-authors. The CDC, the IOM of the National Academy of Sciences, and the UK National Health Service have all concluded that there is no evidence of a link between the MMR vaccine and autism. A systematic review by the Cochrane Library concluded that there is no credible link between the MMR vaccine and autism, that MMR has prevented diseases that still carry a heavy burden of death and complications, that the lack of confidence in MMR has damaged public health, and that design and reporting of safety outcomes in MMR vaccine studies are largely inadequate.

A special court convened in the United States to review claims under the National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program ruled on 12 February 2009 that parents of autistic children are not entitled to compensation in their contention that certain vaccines caused autism in their children.THERESA CEDILLO and MICHAEL CEDILLO, as parents and natural guardians of Michelle Cedillo vs. Secretary of Health and Human Services, 98-916V (United States Court of Federal Claims 2009-02-12).</ref>

Prenatal infection

There is evidence that schizophrenia is associated with prenatal exposure to rubella, influenza, and toxoplasmosis infection. For example, one study found a seven-fold increased risk of schizophrenia when mothers were exposed to influenza in the first trimester of gestation. This may have public health implications, as strategies for preventing infection include vaccination, antibiotics, and simple hygiene. When weighing the benefits of protecting the woman and fetus from influenza against the potential risk of vaccine-induced antibodies that could conceivably contribute to schizophrenia, influenza vaccination for women of reproductive age still makes sense, but it is not known whether vaccination during pregnancy helps or harms. The CDC's Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and the American Academy of Family Physicians all recommend routine flu shots for pregnant women, for several reasons:

- their risk for serious influenza-related medical complications during the last two trimesters;

- their greater rates for flu-related hospitalizations compared to nonpregnant women;

- the possible transfer of maternal anti-influenza antibodies to children, protecting the children from the flu; and

- several studies that found no harm to pregnant women or their children from the vaccinations.

Despite this recommendation, only 16% of healthy pregnant U.S. women surveyed in 2005 had been vaccinated against the flu.

Aluminum

Aluminum compounds are used as immunologic adjuvants to increase the effectiveness of many vaccines. Although in some cases these compounds have been associated with redness, itching, and low-grade fever, and aluminum as such is considered neurotoxic for humans, its use in vaccines has not been associated with serious adverse events. In some cases aluminum-containing vaccines are associated with macrophagic myofasciitis (MMF), localized microscopic lesions containing aluminum salts that persist up to 8 years. However, recent case-controlled studies have found no specific clinical symptoms in individuals with biopsies showing MMF, and there is no evidence that aluminum-containing vaccines are a serious health risk or justify changes to immunization practice.

Individual liberty

Further information: Vaccination policyCompulsory vaccination policies have provoked opposition at various times from people who say that governments should not infringe on the freedom of an individual to choose medications, even if the choice increases the risk of disease to others. If a vaccination program successfully reduces the disease threat, it may reduce the perceived risk of disease enough so that an individual's optimal strategy is to refuse vaccination at coverage levels below those optimal for the community. If many exemptions are granted to mandatory vaccination rules, the resulting free rider problem may cause loss of herd immunity, substantially increasing risks even to vaccinated individuals.

Religion

Main article: Vaccination and religionVaccination has been opposed on religious grounds ever since it was introduced, even when vaccination is not compulsory. Some Christian opponents argued, when vaccination was first becoming widespread, that if God had decreed that someone should die of smallpox, it would be a sin to thwart God's will via vaccination. Religious opposition continues to the present day, on various grounds, raising ethical difficulties when the number of unvaccinated children threatens harm to the entire population. Many governments allow parents to opt out of their children's otherwise-mandatory vaccinations for religious reasons; some parents falsely claim religious beliefs to get vaccination exemptions.

Alternative medicine

Many forms of alternative medicine are based on philosophies that oppose vaccination and have practitioners who voice their opposition. These include anthroposophy, some elements of the chiropractic community, non-medically trained homoeopaths, and naturopaths.

Historically, chiropractic strongly opposed vaccination based on its belief that all diseases were traceable to causes in the spine, and therefore could not be affected by vaccines; Daniel D. Palmer, the founder of chiropractic, wrote, "It is the very height of absurdity to strive to 'protect' any person from smallpox or any other malady by inoculating them with a filthy animal poison." Vaccination remains controversial within chiropractic. Although most chiropractic writings on vaccination focus on its negative aspects, antivaccination sentiment is espoused by what appears to be a minority of chiropractors. The American Chiropractic Association and the International Chiropractic Association support individual exemptions to compulsory vaccination laws, and a 1995 survey of U.S. chiropractors found that about a third believed there was no scientific proof that immunization prevents disease.While the Canadian Chiropractic Association supports vaccination, a survey in Alberta in 2002 found that 25% of chiropractors advised patients for, and 27% against, vaccinating themselves or their children.

Although most chiropractic colleges try to teach about vaccination responsibly, several have faculty who seem to stress negative views. A survey of a 1999–2000 cross section of students of Canadian Memorial Chiropractic College, which does not formally teach antivaccination views, reported that fourth-year students opposed vaccination more strongly than first-years, with 29.4% of fourth-years opposing vaccination.

Several surveys have shown that some practitioners of homeopathy, particularly homeopaths without any medical training, advise patients against vaccination. For example, a survey of registered homeopaths in Austria found that only 28% considered immunization to be an important preventive measure, and 83% of homeopaths surveyed in Sydney, Australia did not recommend vaccination. Many practitioners of naturopathy also oppose vaccination.

Financial motives

For many vaccines, the financial risks for producers are great and market returns are usually minimal. Critics state that the profit motive explains why vaccination is required, and that vaccine makers cover up or suppress information, or generate misinformation, about safety or effectiveness.

Some vaccine critics allegedly have financial motives for criticizing vaccines. Legal counsel and expert witnesses employed in anti-vaccine cases may be motivated by profit.

Dispute resolution

Main article: Vaccine courtThe U.S. Vaccine Injury Compensation Program (VICP) was created to provide a federal no-fault system for compensating vaccine-related injuries or death. It was established after a scare in the 1980s over the DPT vaccine: even though claims of side effects were later generally discredited, large jury awards had been given to some claimants of DPT vaccine injuries, and most DPT vaccine makers had ceased production. Claims against vaccine manufacturers must be heard first in the vaccine court. By 2008 the fund had paid out 2,114 awards totaling $1.7 billion. Thousands of cases of autism-related claims are pending before the court, and have not yet been resolved. In 2008 the government conceded one case concerning a child who had a pre-existing mitochondrial disorder and whose autism-like symptoms came after five simultaneous injections against nine diseases.

History

Religious arguments against inoculation were advanced even before the work of Edward Jenner; for example, in a 1722 sermon entitled "The Dangerous and Sinful Practice of Inoculation" the English theologian Rev. Edward Massey argued that diseases are sent by God to punish sin and that any attempt to prevent smallpox via inoculation is a "diabolical operation". Some anti-vaccinationists still base their stance against vaccination with reference to their religious beliefs.

After Jenner's work, vaccination became widespread in the United Kingdom in the early 1800s. Variolation, which had preceded vaccination, was banned in 1840 because of its greater risks. Public policy and successive Vaccination Acts first encouraged vaccination and then made it mandatory for all infants in 1853, with the highest penalty for refusal being a prison sentence. This was a significant change in the relationship between the British state and its citizens, and there was a public backlash. After an 1867 law extended the requirement to age 14 years, its opponents focused concern on infringement of individual freedom, and eventually a 1898 law allowed for conscientious objection to compulsory vaccination.

In the 19th century, the city of Leicester in the UK achieved a high level of isolation of smallpox cases and great reduction in spread compared to other areas. The mainstay of Leicester's approach to conquering smallpox was to decline vaccination and put their public funds into sanitary improvements. Bigg's account of the public health procedures in Leicester, presented as evidence to the Royal Commission, refers to erysipelas, an infection of the superficial tissues which was a complication of any surgical procedure.

In the U.S., President Thomas Jefferson took a close interest in vaccination, alongside Dr. Waterhouse, chief physician at Boston. Jefferson encouraged the development of ways to transport vaccine material through the Southern states, which included measures to avoid damage by heat, a leading cause of ineffective batches. Smallpox outbreaks were contained by the latter half of the 19th century, a development widely attributed to vaccination of a large portion of the population. Vaccination rates fell after this decline in smallpox cases, and the disease again became epidemic in the 1870s (see smallpox).

Anti-vaccination activity increased again in the U.S. in the late 19th century. After a visit to New York in 1879 by William Tebb, a prominent British anti-vaccinationist, the Anti-Vaccination Society of America was founded. The New England Anti-Compulsory Vaccination League was formed in 1882, and the Anti-Vaccination League of New York City in 1885.

John Pitcairn, the wealthy founder of the Pittsburgh Plate Glass Company (now PPG Industries) emerged as a major financer and leader of the American anti-vaccination movement. On March 5, 1907, in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, he delivered an address to the Committee on Public Health and Sanitation of the Pennsylvania General Assembly criticizing vaccination. He later sponsored the National Anti-Vaccination Conference, which, held in Philadelphia on October, 1908, led to the creation of The Anti-Vaccination League of America. When the League was organized later that month, Pitcairn was chosen to be its first president. On December 1, 1911, he was appointed by Pennsylvania Governor John K. Tener to the Pennsylvania State Vaccination Commission, and subsequently authored a detailed report strongly opposing the Commission's conclusions.. He continued to be a staunch opponent of vaccination until his death in 1916.

In November 1904, in response to years of inadequate sanitation and disease, followed by a poorly-explained public health campaign led by the renowned Brazilian public health official Oswaldo Cruz, citizens and military cadets in Rio de Janeiro arose in a Revolta da Vacina or Vaccine Revolt. Riots broke out on the day a vaccination law took effect; vaccination symbolized the most feared and most tangible aspect of a public health plan that included other features such as urban renewal that many had opposed for years.

In the early 19th century, the anti-vaccination movement drew members from across a wide range of society; more recently, it has been reduced to a predominantly middle-class phenomenon. Arguments against vaccines in the 21st century are often similar to those of 19th-century anti-vaccinationists.

References

- ^ Bonhoeffer J, Heininger U (2007). "Adverse events following immunization: perception and evidence". Curr Opin Infect Dis. 20 (3): 237–46. doi:10.1097/QCO.0b013e32811ebfb0. PMID 17471032.

- ^ Demicheli V, Jefferson T, Rivetti A, Price D (2005). "Vaccines for measles, mumps and rubella in children". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 19 (4). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004407.pub2. PMID 16235361.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|laydate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysource=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysummary=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wolfe R, Sharp L (2002). "Anti-vaccinationists past and present". BMJ. 325 (7361): 430–2. doi:10.1136/bmj.325.7361.430. PMID 12193361.

- Fenner F, Henderson DA, Arita I, Ježek Z, Ladnyi, ID (1988). Smallpox and its Eradication (PDF). Geneva: World Health Organization. ISBN 92-4-156110-6. Retrieved 2007-09-04.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Sutter RW, Maher C (2006). "Mass vaccination campaigns for polio eradication: an essential strategy for success". Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 304: 195–220. doi:10.1007/3-540-36583-4_11. PMID 16989271.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2002). "Progress toward elimination of Haemophilus influenzae type b invasive disease among infants and children—United States, 1998–2000". MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 51 (11): 234–7. PMID 11925021.

- Park A (2008-05-21). "How safe are vaccines?". TIME.

- Dr. med. Gerhard Buchwald (Ref: The Vaccination Nonsense. ISBN 3-8334-2508-3 page 108. Asserts that vaccination has never provided any benefit.

- ^ Morrell, Peter (October 13, 2000). "eLetters: Vaccination: the wider picture?". Canadian Medical Association Journal. Retrieved 2007-11-23.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Ernst E (2001). "Rise in popularity of complementary and alternative medicine: reasons and consequences for vaccination". Vaccine. 20 (Suppl 1): S89–93. doi:10.1016/S0264-410X(01)00290-0. PMID 11587822.

- Galazka AM, Robertson SE (1995). "Diphtheria: changing patterns in the developing world and the industrialized world". Eur J Epidemiol. 11 (1): 107–17. doi:10.1007/BF01719955. PMID 7489768.

- Halvorsen R (2007). The Truth about Vaccines. Gibson Square. ISBN 9781903933923.

- Salmon DA, Haber M, Gangarosa EJ, Phillips L, Smith NJ, Chen RT (1999). "Health consequences of religious and philosophical exemptions from immunization laws: individual and societal risk of measles". JAMA. 282 (1): 47–53. doi:10.1001/jama.282.1.47. PMID 10404911.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Feikin DR, Lezotte DC, Hamman RF, Salmon DA, Chen RT, Hoffman RE (2000). "Individual and community risks of measles and pertussis associated with personal exemptions to immunization". JAMA. 284 (24): 3145–50. doi:10.1001/jama.284.24.3145. PMID 11135778.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Zhou F, Santoli J, Messonnier ML; et al. (2005). "Economic evaluation of the 7-vaccine routine childhood immunization schedule in the United States, 2001". Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 159 (12): 1136–44. doi:10.1001/archpedi.159.12.1136. PMID 16330737.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gangarosa EJ, Galazka AM, Wolfe CR; et al. (1998). "Impact of anti-vaccine movements on pertussis control: the untold story". Lancet. 351 (9099): 356–61. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(97)04334-1. PMID 9652634.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Allen A (2002). "Bucking the herd". The Atlantic. 290 (2): 40–2. Retrieved 2007-11-07.

- "What would happen if we stopped vaccinations?". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2007-06-12. Retrieved 2008-04-25.

- Nelson MC, Rogers J (1992). "The right to die? Anti-vaccination activity and the 1874 smallpox epidemic in Stockholm". Soc Hist Med. 5 (3): 369–88. doi:10.1093/shm/5.3.369. PMID 11645870.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2007). "Pertussis". In Atkinson W, Hamborsky J, McIntyre L, Wolfe S (ed.). Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases. Washington, DC: Public Health Foundation.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2000). "Measles outbreak—Netherlands, April 1999–January 2000". MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 49 (14): 299–303. PMID 10825086.

- Pepys MB (2007). "Science and serendipity". Clin Med. 7 (6): 562–78. PMID 18193704.

- "Measles outbreak feared". BBC News. 30 May, 2000. Retrieved 2007-11-23.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - McBrien J, Murphy J, Gill D, Cronin M, O'Donovan C, Cafferkey M (2003). "Measles outbreak in Dublin, 2000". Pediatr Infect Dis J. 22 (7): 580–4. doi:10.1097/00006454-200307000-00002. PMID 12867830.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Clements CJ, Greenough P, Schull D (2006). "How vaccine safety can become political – the example of polio in Nigeria" (PDF). Curr Drug Saf. 1 (1): 117–9. doi:10.2174/157488606775252575.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Wild poliovirus 2000–2008" (PDF). Global Polio Eradication Initiative. 2008-02-05. Retrieved 2008-02-11.

- "'Hundreds' dead in measles outbreak". IRIN. 2007-12-14. Retrieved 2008-02-10.

- Parker A, Staggs W, Dayan G; et al. (2006). "Implications of a 2005 measles outbreak in Indiana for sustained elimination of measles in the United States". N Engl J Med. 355 (5): 447–55. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa060775. PMID 16885548.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Fair E, Murphy TV, Golaz A, Wharton M (2002). "Philosophic objection to vaccination as a risk for tetanus among children younger than 15 years". Pediatrics. 109 (1): e2. doi:10.1542/peds.109.1.e2. PMID 11773570.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - The Lancet Infectious Diseases (2007). "Tackling negative perceptions towards vaccination". Lancet Infect Dis. 7 (4): 235. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70057-9. PMID 17376373.

- Hilton S, Petticrew M, Hunt K (2006). "'Combined vaccines are like a sudden onslaught to the body's immune system': parental concerns about vaccine 'overload' and 'immune-vulnerability'". Vaccine. 24 (20): 4321–7. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.03.003. PMID 16581162.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Black, Steven (July 2000). "Efficacy, Safety, and Immunogenicity of Heptavalent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine in Children". The American Journal of Managed Care. 19 (3): 187-195. PMID 10749457.

- Murphy, Timothy (June 1996). "Branhamella catarrhalis: Epidemiology, Surface Antigenic Structure, and Immune Response". Microbiological Reviews. 60 (2): 267–279.

- Sloyer, John; Howie, Virgil; Ploussard, John; Amman, Arthur; Austrian, Richard; Johnston (June 1974). "Immune Response to Acute Otistis Media in Children". Infection and Immunity. 9 (6): 1028-1032.

- ^ Gerber JS, Offit PA (2009). "Vaccines and autism: a tale of shifting hypotheses". Clin Infect Dis. 48 (4): 456–61. doi:10.1086/596476. PMID 19128068.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|laydate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysource=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysummary=ignored (help) - ^ Sugarman SD (2007). "Cases in vaccine court—legal battles over vaccines and autism". N Engl J Med. 357 (13): 1275–7. doi:10.1056/NEJMp078168. PMID 17898095.

- ^ Offit PA (2007). "Thimerosal and vaccines—a cautionary tale". N Engl J Med. 357 (13): 1278–9. doi:10.1056/NEJMp078187. PMID 17898096.

- Immunization Safety Review Committee (2004). Immunization Safety Review: Vaccines and Autism. The National Academies Press. ISBN 0-309-09237-X.

- Doja A, Roberts W (2006). "Immunizations and autism: a review of the literature". Can J Neurol Sci. 33 (4): 341–6. PMID 17168158.

- Wakefield A, Murch S, Anthony A; et al. (1998). "Ileal-lymphoid-nodular hyperplasia, non-specific colitis, and pervasive developmental disorder in children". Lancet. 351 (9103): 637–41. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(97)11096-0. PMID 9500320. Retrieved 2007-09-05.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - National Health Service (2004). "MMR: myths and truths". Retrieved 2007-09-03.

- "Doctors issue plea over MMR jab". BBC News. 2006-06-26. Retrieved 2007-11-23.

- ^ "MMR scare doctor 'paid children'". BBC News. 2007-07-16. Retrieved 2007-11-23.

- Deer B (2009-02-08). "MMR doctor Andrew Wakefield fixed data on autism". Sunday Times. Retrieved 2009-02-09.

- Murch SH, Anthony A, Casson DH; et al. (2004). "Retraction of an interpretation". Lancet. 363 (9411): 750. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15715-2. PMID 15016483.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Autism and Vaccines Theory, from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control. Accessed June 13 2007.

- Immunization Safety Review: Vaccines and Autism. From the Institute of Medicine of the National Academy of Sciences. Report dated May 17 2004; accessed June 13 2007.

- MMR Fact Sheet, from the United Kingdom National Health Service. Accessed June 13 2007.

- "Vaccine didn't cause autism, court rules". CNN. 2009-02-12. Retrieved 2009-02-12.

- Cite error: The named reference

rejectedclaimwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - Brown AS (2006). "Prenatal infection as a risk factor for schizophrenia". Schizophr Bull. 32 (2): 200–2. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbj052. PMID 16469941.

- Arehart-Treichel J (2007). "Schizophrenia risk factor found in maternal blood". Psychiatr News. 42 (3): 22.

- ^ Fiore AE, Shay DK, Haber P; et al. (2007). "Prevention and control of influenza: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2007". MMWR Recomm Rep. 56 (RR-6): 1–54.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Baylor NW, Egan W, Richman P (2002). "Aluminum salts in vaccines—US perspective". Vaccine. 20 (Suppl 3): S18–23. doi:10.1016/S0264-410X(02)00166-4.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Corrigendum (2002). Vaccine 20 (27–8): 3428. doi:10.1016/S0264-410X(02)00307-9 PMID 12184360. - ^ François G, Duclos P, Margolis H; et al. (2005). "Vaccine safety controversies and the future of vaccination programs". Pediatr Infect Dis J. 24 (11): 953–61. doi:10.1097/01.inf.0000183853.16113.a6. PMID 16282928.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Colgrove J, Bayer R (2005). "Manifold restraints: liberty, public health, and the legacy of Jacobson v Massachusetts". Am J Public Health. 95 (4): 571–6. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2004.055145. PMID 15798111.

- Fine PE, Clarkson JA (1986). "Individual versus public priorities in the determination of optimal vaccination policies". Am J Epidemiol. 124 (6): 1012–20. PMID 3096132.

- ^ May T, Silverman RD (2005). "Free-riding, fairness and the rights of minority groups in exemption from mandatory childhood vaccination" (PDF). Hum Vaccin. 1 (1): 12–5. PMID 17038833.

- ^

Early religious opposition:

- White AD (1896). "Theological opposition to inoculation, vaccination, and the use of anæsthetics". A History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom. New York: Appleton.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - Bazin H (2001). "The ethics of vaccine usage in society: lessons from the past". Endeavour. 25 (3): 104–8. doi:10.1016/S0160-9327(00)01376-4. PMID 11725304.

- Noble M (2005). "Ethics in the trenches: a multifaceted analysis of the stem cell debate". Stem Cell Rev. 1 (4): 345–76. doi:10.1385/SCR:1:4:345. PMID 17142878.

- White AD (1896). "Theological opposition to inoculation, vaccination, and the use of anæsthetics". A History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom. New York: Appleton.

- LeBlanc S (2007-10-17). "Parents use religion to avoid vaccines". USA Today. Retrieved 2007-11-24.

- ^ Busse JW, Morgan L, Campbell JB (2005). "Chiropractic antivaccination arguments". J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 28 (5): 367–73. doi:10.1016/j.jmpt.2005.04.011. PMID 15965414.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Campbell JB, Busse JW, Injeyan HS (2000). "Chiropractors and vaccination: a historical perspective". Pediatrics. 105 (4): e43. doi:10.1542/peds.105.4.e43. PMID 10742364.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Russell ML, Injeyan HS, Verhoef MJ, Eliasziw M (2004). "Beliefs and behaviours: understanding chiropractors and immunization". Vaccine. 23 (3): 372–9. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.05.027. PMID 15530683.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Busse JW, Wilson K, Campbell JB (2008). "Attitudes towards vaccination among chiropractic and naturopathic students". Vaccine. 26 (49): 6237–42. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.07.020. PMID 18674581.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Schmidt K, Ernst E (2003). "MMR vaccination advice over the Internet". Vaccine. 21 (11–12): 1044–7. doi:10.1016/S0264-410X(02)00628-X. PMID 12559777.

- Goodman JL (2005-05-04). "Statement before the Committee on Energy and Commerce, U.S. House of Representatives". U.S. Food and Drug Administration Office of Legislation. Retrieved 2008-06-15.

- Fitzpatrick M (2007-07-04). "'The MMR-autism theory? There's nothing in it'". spiked. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- "National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program statistics reports". Health Resources and Services Administration. 2008-01-08. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- Poling case:

- Stobbe M, Marchione M (2008-03-07). "Analysis: vaccine-autism link unproven". Associated Press. Retrieved 2008-06-06.

- Honey K (2008). "Attention focuses on autism". J Clin Invest. 118 (5): 1586–7. doi:10.1172/JCI35821. PMID 18451989.

- Offit PA (2008). "Vaccines and autism revisited—the Hannah Poling case". N Engl J Med. 358 (20): 2089–91. doi:10.1056/NEJMp0802904. PMID 18480200.

- "Vaccination - A Crime Against Humanity". The Associated Jehovah's Witnesses for Reform on Blood. Retrieved 2006-11-02.

- Ellner P (1998). "Smallpox: gone but not forgotten". Infection. 26 (5): 263–9. doi:10.1007/BF02962244. PMID 9795781.

- Eddy TP (1992). "The Leicester anti-vaccination movement". Lancet. 340 (8830): 1298. doi:10.1016/0140-6736(92)93006-9. PMID 1359363.

- Fourth and other reports of the Royal Commission into smallpox and Leicester 1871 et seq

- (U.S.) Center for Disease Control

- Pitcairn, John (1907), Vaccination, Anti-Vaccination League of Pennsylvania

- ^ Higgins, Charles Michael (1920), Horrors of Vaccination Exposed and Illustrated: "Life Sketch of John Pitcairn By A Philadelphia Friend", Brooklyn, New York: C.M. Higgins

- Meade T (1989). "'Living worse and costing more': resistance and riot in Rio de Janeiro, 1890–1917". J Lat Am Stud. 21 (2): 241–66.

- Fitzpatrick M (2005). "The anti-vaccination movement in England, 1853–1907". J R Soc Med. 98 (8): 384–5. doi:10.1258/jrsm.98.8.384.

Further reading

- Bedford H, Elliman D (2000). "Concerns about immunisation". BMJ. 320 (7229): 240–3. doi:10.1136/bmj.320.7229.240. PMID 10642238.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Davies P, Chapman S, Leask J (2002). "Antivaccination activists on the world wide web". Arch Dis Child. 87 (1): 22–5. doi:10.1136/adc.87.1.22. PMID 12089115.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Elliman D, Bedford H (2004). "MMR: Science and Fiction. Exploring the Vaccine Crisis; MMR and Autism: What Parents Need to Know". BMJ. 329 (7473): 1049. doi:10.1136/bmj.329.7473.1049.

- Friedlander E (2007). "The anti-immunization activists: a pattern of deception". Retrieved 2007-11-13.

- Hanratty B, Holt T, Duffell E, Patterson W, Ramsay M, White J, Jin L, Litton P (2000). "UK measles outbreak in non-immune anthroposophic communities: the implications for the elimination of measles from Europe". Epidemiol Infect. 125 (2): 377–83. doi:10.1017/S0950268899004525. PMID 11117961.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Miller, C.L. Deaths from Measles in England and Wales. 1970-83.], Epidemiological Research Laboratory, Public Health Laboratory Service, London; measles mortality statistics published in the British Medical Journal, Vol 290, February 9, 1985

- Myers, M (2008). Do Vaccines Cause That? A Guide for Evaluating Vaccine Safety Concerns. Galveston, TX: Immunizations for Public Health (i4ph). ISBN 0976902710.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Offit PA (2008). Autism's False Prophets: Bad Science, Risky Medicine, and the Search for a Cure. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-14636-4.

- Orenstein W, Hinman A (1999). "The immunization system in the United States - the role of school immunization laws". Vaccine. 17 Suppl 3: S19–24. doi:10.1016/S0264-410X(99)00290-X. PMID 10559531.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Poland G, Jacobson R (2001). "Understanding those who do not understand: a brief review of the anti-vaccine movement". Vaccine. 19 (17–19): 2440–5. doi:10.1016/S0264-410X(00)00469-2. PMID 11257375.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Sears R (2007). The Vaccine Book: Making the Right Decision for Your Child. Little, Brown. ISBN 0316017507. For a review of this book, see: Offit PA, Moser CA (2009). "The problem with Dr Bob's alternative vaccine schedule". Pediatrics. 123 (1): e164–9. doi:10.1542/peds.2008-2189. PMID 19117838.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|laydate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysource=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysummary=ignored (help) - Spier R (1998). "Ethical aspects of vaccines and vaccination". Vaccine. 16 (19): 1788–94. doi:10.1016/S0264-410X(98)00169-8. PMID 9795382.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Vermeersch E (1999). "Individual rights versus societal duties". Vaccine. 17 Suppl 3: S14–7. PMID 10627239.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Wolfe RM, Sharp LK, Lipsky MS (2002). "Content and design attributes of antivaccination web sites". JAMA. 287 (24): 3245–8. doi:10.1001/jama.287.24.3245. PMID 12076221.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Six common misconceptions about immunization". World Health Organization. 16 February 2006. Retrieved 2006-11-02.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)

- Anti-vaccinationist publications

- 1884 Compulsory Vaccination in England by William Tebb

- 1885 The Story of a Great Delusion by William White

- 1898 Vaccination A Delusion by Alfred Russel Wallace

- 1936 The Case Against Vaccination by M. Beddow Bayly M.R.C.S., L.R.C.P.

- 1951 The Truth About Vaccination and Immunization by Lily Loat

- 1957 The Poisoned Needle by Eleanor McBean

- 1990 Universal Immunization: Miracle or Masterful Mirage by Dr. Raymond Obomsawin

- 1993 Vaccination: 100 years of orthodox research shows that vaccines represent an assault on the immune system by Viera Scheibner. ISBN 0-646-15124-X

- 2000 Behavioural Problems in Childhood by Viera Scheibner. ISBN 0-9578007-0-3

External links

- Template:Dmoz

- Immunizations, vaccines and biologicals - World Health Organization

- Vaccines & immunizations - Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

| Artificial induction of immunity / Immunization: Vaccines, Vaccination, Infection, Inoculation (J07) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Development | |||||||||||

| Classes | |||||||||||

| Administration | |||||||||||

| Vaccines |

| ||||||||||

| Inventors/ researchers | |||||||||||

| Controversy | |||||||||||

| Related | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||