| Revision as of 22:47, 20 May 2009 view sourceStuarto9 (talk | contribs)22 edits →Chemical structure← Previous edit | Revision as of 22:47, 20 May 2009 view source Vicenarian (talk | contribs)11,582 editsm Reverted edits by Stuarto9 to last revision by Vicenarian (HG)Next edit → | ||

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

| These examples of fats can be categorized into ]s and ]s. | These examples of fats can be categorized into ]s and ]s. | ||

| ==Chemical structure== | |||

| ==fuck you fatasses== | |||

| ] molecule]] | |||

| lolololololol]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]] | |||

| There are many different kinds of fats, but each is a variation on the same chemical structure. All fats consist of ]s (chains of ] and ] atoms, with a ] group at one end) bonded to a backbone structure, often ] (a "backbone" of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen). Chemically, this is a ] of glycerol, an ester being the molecule formed from the reaction of the carboxylic acid and an organic alcohol. As a simple visual illustration, if the kinks and ] of these chains were straightened out, the molecule would have the shape of a capital letter E. The fatty acids would each be a horizontal line; the glycerol "backbone" would be the vertical line that joins the horizontal lines. Fats therefore have "ester" ]. | |||

| The properties of any specific fat molecule depend on the particular fatty acids that constitute it. Different fatty acids are comprised of different numbers of carbon and hydrogen atoms. The carbon atoms, each bonded to two neighboring carbon atoms, form a zigzagging chain; the more carbon atoms there are in any fatty acid, the longer its chain will be. Fatty acids with long chains are more susceptible to intermolecular forces of attraction (in this case, ]), raising its ]. Long chains also yield more ] per molecule when metabolized. | |||

| A fat's constituent fatty acids may also differ in the number of hydrogen atoms that are bonded to the chain of carbon atoms. Each carbon atom is typically bonded to two hydrogen atoms. When a fatty acid has this typical arrangement, it is called ], because the carbon atoms are saturated with hydrogen; meaning they are ] to as many hydrogens as possible. In other fats, a carbon atom may instead bond to only one other hydrogen atom, and have a ] to a neighboring carbon atom. This results in an "unsaturated" fatty acid. More specifically, it would be a "monounsaturated" fatty acid, whereas, a "polyunsaturated" fatty acid would be a fatty acid with more than one double bond. | |||

| Saturated and unsaturated fats differ in their energy content and melting point. Since an unsaturated fat contains fewer carbon-hydrogen bonds than a saturated fat with the same number of carbon atoms, unsaturated fats will yield slightly less energy during metabolism than saturated fats with the same number of carbon atoms. Saturated fats can stack themselves in a closely packed arrangement, so they can freeze easily and are typically solid at room temperature. But the rigid double bond in an unsaturated fat fundamentally changes the chemistry of the fat. There are two ways the double bond may be arranged: the isomer with both parts of the chain on the same side of the double bond (the '']''-isomer), or the isomer with the parts of the chain on opposite sides of the double bond (the '']''-isomer). Most ''trans''-isomer fats (commonly called ]s) are commercially produced rather than naturally occurring. The ''cis''-isomer introduces a kink into the molecule that prevents the fats from stacking efficiently as in the case of fats with saturated chains. This decreases intermolecular forces between the fat molecules, making it more difficult for unsaturated cis-fats to freeze; they are typically liquid at room temperature. Trans fats may still stack like saturated fats, and are not as susceptible to metabolization as other fats. Trans fats and saturated fats significantly increase the risk of ].<ref name=nejmreview>{{cite journal|author= Mozaffarian D, Katan MB, Ascherio A, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC|title= Trans Fatty Acids and Cardiovascular Disease|year=2006|journal=New England Journal of Medicine|volume=354|issue=15|pages=1601–1613|month=April|day=13|doi= 10.1056/NEJMra054035|pmid= 16611951}} PMID 16611951</ref> | |||

| ==Importance for living organisms== | ==Importance for living organisms== | ||

Revision as of 22:47, 20 May 2009

For other uses, see fat (disambiguation) and body fat.

| Types of fats in food |

|---|

| Components |

| Manufactured fats |

Fats consist of a wide group of compounds that are generally soluble in organic solvents and largely insoluble in water. Chemically, fats are generally triesters of glycerol and fatty acids. Fats may be either solid or liquid at normal room temperature, depending on their structure and composition. Although the words "oils", "fats", and "lipids" are all used to refer to fats, "oils" is usually used to refer to fats that are liquids at normal room temperature, while "fats" is usually used to refer to fats that are solids at normal room temperature. "Lipids" is used to refer to both liquid and solid fats, along with other related substances. The word "oil" is used for any substance that does not mix with water and has a greasy feel, such as petroleum (or crude oil) and heating oil, regardless of its chemical structure.

Fats form a category of lipid, distinguished from other lipids by their chemical structure and physical properties. This category of molecules is important for many forms of life, serving both structural and metabolic functions. They are an important part of the diet of most heterotrophs (including humans). Fats or lipids are broken down in the body by enzymes called lipases produced in the pancreas.

Examples of edible animal fats are lard (pig fat), fish oil, and butter or ghee. They are obtained from fats in the milk, meat and under the skin of the animal. Examples of edible plant fats are peanut, soya bean, sunflower, sesame, coconut, olive, and vegetable oils. Margarine and vegetable shortening, which can be derived from the above oils, are used mainly for baking. These examples of fats can be categorized into saturated fats and unsaturated fats.

Chemical structure

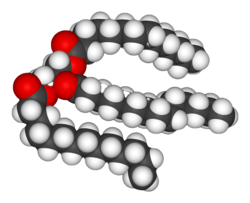

There are many different kinds of fats, but each is a variation on the same chemical structure. All fats consist of fatty acids (chains of carbon and hydrogen atoms, with a carboxylic acid group at one end) bonded to a backbone structure, often glycerol (a "backbone" of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen). Chemically, this is a triester of glycerol, an ester being the molecule formed from the reaction of the carboxylic acid and an organic alcohol. As a simple visual illustration, if the kinks and angles of these chains were straightened out, the molecule would have the shape of a capital letter E. The fatty acids would each be a horizontal line; the glycerol "backbone" would be the vertical line that joins the horizontal lines. Fats therefore have "ester" bonds.

The properties of any specific fat molecule depend on the particular fatty acids that constitute it. Different fatty acids are comprised of different numbers of carbon and hydrogen atoms. The carbon atoms, each bonded to two neighboring carbon atoms, form a zigzagging chain; the more carbon atoms there are in any fatty acid, the longer its chain will be. Fatty acids with long chains are more susceptible to intermolecular forces of attraction (in this case, van der Waals forces), raising its melting point. Long chains also yield more energy per molecule when metabolized.

A fat's constituent fatty acids may also differ in the number of hydrogen atoms that are bonded to the chain of carbon atoms. Each carbon atom is typically bonded to two hydrogen atoms. When a fatty acid has this typical arrangement, it is called "saturated", because the carbon atoms are saturated with hydrogen; meaning they are bonded to as many hydrogens as possible. In other fats, a carbon atom may instead bond to only one other hydrogen atom, and have a double bond to a neighboring carbon atom. This results in an "unsaturated" fatty acid. More specifically, it would be a "monounsaturated" fatty acid, whereas, a "polyunsaturated" fatty acid would be a fatty acid with more than one double bond. Saturated and unsaturated fats differ in their energy content and melting point. Since an unsaturated fat contains fewer carbon-hydrogen bonds than a saturated fat with the same number of carbon atoms, unsaturated fats will yield slightly less energy during metabolism than saturated fats with the same number of carbon atoms. Saturated fats can stack themselves in a closely packed arrangement, so they can freeze easily and are typically solid at room temperature. But the rigid double bond in an unsaturated fat fundamentally changes the chemistry of the fat. There are two ways the double bond may be arranged: the isomer with both parts of the chain on the same side of the double bond (the cis-isomer), or the isomer with the parts of the chain on opposite sides of the double bond (the trans-isomer). Most trans-isomer fats (commonly called trans fats) are commercially produced rather than naturally occurring. The cis-isomer introduces a kink into the molecule that prevents the fats from stacking efficiently as in the case of fats with saturated chains. This decreases intermolecular forces between the fat molecules, making it more difficult for unsaturated cis-fats to freeze; they are typically liquid at room temperature. Trans fats may still stack like saturated fats, and are not as susceptible to metabolization as other fats. Trans fats and saturated fats significantly increase the risk of coronary heart disease.

Importance for living organisms

Vitamins A, D, E, and K are fat-soluble, meaning they can only be digested, absorbed, and transported in conjunction with fats. Fats are also sources of essential fatty acids, an important dietary requirement.

Fats play a vital role in maintaining healthy skin and hair, insulating body organs against shock, maintaining body temperature, and promoting healthy cell function. They also serve as energy stores for the body. Fats are broken down in the body to release glycerol and free fatty acids. The glycerol can be converted to glucose by the liver and thus used as a source of energy.

Fat also serves as a useful buffer towards a host of diseases. When a particular substance, whether chemical or biotic—reaches unsafe levels in the bloodstream, the body can effectively dilute—or at least maintain equilibrium of—the offending substances by storing it in new fat tissue. This helps to protect vital organs, until such time as the offending substances can be metabolized and/or removed from the body by such means as excretion, urination, accidental or intentional bloodletting, sebum excretion, and hair growth.

While it is nearly impossible to remove fat completely from the diet, it would be unhealthy to do so. Some fatty acids are essential nutrients, meaning that they can't be produced in the body from other compounds and need to be consumed in small amounts. All other fats required by the body are non-essential and can be produced in the body from other compounds.

Adipose tissue

In animals, adipose, or fatty tissue is the body's means of storing metabolic energy over extended periods of time. Depending on current physiological conditions, adipocytes store fat derived from the diet and liver metabolism or degrade stored fat to supply fatty acids and glycerol to the circulation. These metabolic activities are regulated by several hormones (i.e., insulin, glucagon and epinephrine). The location of the tissue determines its metabolic profile: "Visceral fat" is located within the abdominal wall (i.e., beneath the wall of abdominal muscle) whereas "subcutaneous fat" is located beneath the skin (and includes fat that is located in the abdominal area beneath the skin but above the abdominal muscle wall). Visceral fat was recently discovered to be a significant producer of signaling chemicals (ie, hormones), among which are several which are involved in inflammatory tissue responses. One of these is resistin which has been linked to obesity, insulin resistance, and Type 2 diabetes. This latter result is currently controversial, and there have been reputable studies supporting all sides on the issue.

See also

References

- Maton, Anthea (1993). Human Biology and Health. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, USA: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-981176-1. OCLC 32308337.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Mozaffarian D, Katan MB, Ascherio A, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC (2006). "Trans Fatty Acids and Cardiovascular Disease". New England Journal of Medicine. 354 (15): 1601–1613. doi:10.1056/NEJMra054035. PMID 16611951.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|day=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) PMID 16611951

- Donatelle, Rebecca J. (2005). Health, the Basics (6th ed ed.). San Francisco: Pearson Education, Inc. ISBN 0131206877. OCLC 51801859.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help)