| Revision as of 08:08, 26 May 2009 editFuture Perfect at Sunrise (talk | contribs)Edit filter managers, Administrators87,196 edits multiple copyedits, tweaks, removing of redundant links← Previous edit | Revision as of 08:23, 26 May 2009 edit undoYannismarou (talk | contribs)20,442 edits →In the Balkan Wars: you can ask for sources (the fac template), and if not provided within a reasonable time remove; but you cannot remove without providing any explanationNext edit → | ||

| Line 26: | Line 26: | ||

| {{main|Struggle for Macedonia|Balkan Wars}} | {{main|Struggle for Macedonia|Balkan Wars}} | ||

| On the eve of the 20th century Macedonians were a Greek minority population in the northern part of Ottoman Greece living alongside ]/], ], ] and other ethnicities. During the ], Thessaloniki became the prize city for the ] parties, Greece, Bulgaria and Serbia. Greece claimed the region corresponding to that of ]. One of the reasons, was the fact that ] was attributed as part of ]. Another justification for the claim was to liberate the minority population of Greeks that lived in the region. Following the Balkan Wars, Greece obtained the region that is now Greek Macedonia, together with Western Thrace, from the dissolving Ottoman empire. | On the eve of the 20th century Macedonians were a Greek minority population in the northern part of Ottoman Greece living alongside ]/], ], ] and other ethnicities. During the ], Thessaloniki became the prize city for the ] parties, Greece, Bulgaria and Serbia. Greece claimed the region corresponding to that of ]. One of the reasons, was the fact that ] was attributed as part of ]. Another justification for the claim was to liberate the minority population of Greeks that lived in the region. Following the Balkan Wars, Greece obtained the region that is now Greek Macedonia, together with Western Thrace, from the dissolving Ottoman empire. Macedonians fought alongside the regular Greeks, with many victims from the local population. There are monuments in West Macedonia commemorating the Greeks from Macedonia that fought and died in the ] to "''liberate Macedonia''" from the Ottoman rule. | ||

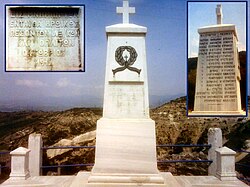

| ] monument commemorating the ''"heroically fallen officers and soldiers, October 1912"''. It was raised at the battle site of Portes ("Πόρτες") outside the village of Prosilio ("Προσήλιο") near ]<ref>Kozani.net, ''] Greek newsblog (in Greek)''</ref>]] | ] monument commemorating the ''"heroically fallen officers and soldiers, October 1912"''. It was raised at the battle site of Portes ("Πόρτες") outside the village of Prosilio ("Προσήλιο") near ]<ref>Kozani.net, ''] Greek newsblog (in Greek)''</ref>]] | ||

Revision as of 08:23, 26 May 2009

This article is about the modern inhabitants of Greek Macedonia; for the ancient people, see ancient Macedonians; for other uses, see Macedonian (disambiguation).

| Part of a series on |

| Greeks |

|---|

|

| By countryNative communities |

|

Groups by regionModern Greece:

Constantinople and Asia Minor: Other regions: Other groups: |

| Greek culture |

| Religion |

Languages and dialectsGreek:

Other languages |

|

History of Greece (Ancient · Byzantine · Ottoman) |

Macedonians (Template:Lang-el) is the term by which ethnic Greeks inhabiting or originating from the region of Macedonia in Greece, are known. The larger part of this population is concentrated in the capital city of Thessaloniki, but many have spread across the whole of Greece and in the diaspora.

Modern Macedonian identity

Preface

The Greek Macedonian identity has its roots in the ancient Macedonians, the people of the kingdom of Macedonia in ancient Greece. During the reign of Alexander the Great and after his death, Macedonians were the protagonists in the spread of Hellenistic culture. After the Roman conquest of Greece the Macedonians and the rest of the Greek population were an integral component of the people of the Roman province of Macedonia. The Greek ethnic element remained an important cultural and ethnographical factor in the region until the modern era, together with other ethnicities that settled in the area (Slavs, Aromanians, Albanians, and later Turks).

In the Middle Ages the Macedonians were a part of the Byzantine Greek (Roman Greek) population. After the Ottoman invasions, Macedonia came under the rule of the the Ottoman Empire. Towards the end of the Ottoman era, the term "Macedonia" came to signify a region in the north of the Greek peninsula different from the previous Byzantine theme. A significant population of Greek Macedonians lived in the region and still maintained the Orthodox Christian religion. Thessaloniki, remained the biggest city where the larger part of Macedonians resided.

In the Greek War of Independence

The Greek War of Independence refers to the efforts of Greeks to establish an independent Greek State, at the time that Greece was a part of the Ottoman Empire. The revolution was initially planned and organized through secret organizations, most notable of which the Filiki Eteria, that operated both in Greece and in Europe outside the Ottoman Empire. Macedonian Greeks were actively involved in those early revolutionary movements; among the first was Grigorios Zalykis (1777-1820), a Greek writer, that founded the Hellenoglosso Xenodocheio organization, a precursor of Filiki Etaireia. The later leader of the Greek War of Independece in Macedonia, Emmanouel Pappas was also a prominent member of Filiki Etaireia.

In the Spring of 1821, Macedonian fighters led by Pappas launched an insurrection against Ottoman Rule, but failed. The Greek Revolution in Macedonia started on Mount Athos, Chalkidiki on May 23, after a force of about 4,000 Macedonian insurgents and some monks gathered in the monasteries there. Quickly, the rise spread to Pieria, Polygyros, Arnaia, Ormylia, Sithonia, the area of Kalamaria, and to northwards to Bitola (Monastiri), Kruševo (Krousovo) and Bogdanci (Vogdantsa). In the beginning some accomplishments where made, when Pappas managed to capture most of the Chalkidiki peninsula and to threaten Thessaloniki. However the force soon retreated to Vasilika, near Thessaloniki. There it was outflanked and overrun by superior Ottoman forces led by Mehmet Emin Pasha. Pappas was at the time named Leader and Defender of Macedonia and is today considered a Greek hero along with the unnamed Macedonians that fought with him.

This defeat, along with the repression of the revolution led by Anastasios Karatasos in Naoussa in April 1822, in Eastern Macedonia with Nikolaos Tsaras and in Siatista with Nikolaos Kasomoulis and Georgios Nioplios, marked the end of the Greek War of Independence in Macedonia, at the time. While the rebellion led to the establishment of the independent [[modern Greek state in the south, which earned international recognition in 1832, Greek resistance movements continued to operate in the territories that remained under Ottoman control, including Macedonia as well as Thessaly, Epirus and Crete.. Events of the Russo-Turkish Crimean War in 1854 ignited a new Macedonian revolt that was spawned in Chalkidiki.. One of the prime instigators of the revolt was Dimitrios or Tsamis Karatasos known by the epithet Yero (Greek:"γέρο" meaning "old"), as Yero-Tsamis or Yero-Karatasos. He was the son of Anastasios Karatasos, the revolutionary of 1821. The insurrections of the Macedonian Greeks had the support of king Otto of Greece, who thought that "liberation" of Macedonia and other parts of Greece was possible, hoping on Russian support. The revolt however failed in its part having deteriorated the Greco-Turkish relations for the years to come.

In the Balkan Wars

Main articles: Struggle for Macedonia and Balkan WarsOn the eve of the 20th century Macedonians were a Greek minority population in the northern part of Ottoman Greece living alongside Macedonian Slavs/Bulgarians, Turks, Jews and other ethnicities. During the Balkan wars, Thessaloniki became the prize city for the struggling parties, Greece, Bulgaria and Serbia. Greece claimed the region corresponding to that of ancient Macedonia. One of the reasons, was the fact that ancient Macedonia was attributed as part of Greek history. Another justification for the claim was to liberate the minority population of Greeks that lived in the region. Following the Balkan Wars, Greece obtained the region that is now Greek Macedonia, together with Western Thrace, from the dissolving Ottoman empire. Macedonians fought alongside the regular Greeks, with many victims from the local population. There are monuments in West Macedonia commemorating the Greeks from Macedonia that fought and died in the Balkan Wars to "liberate Macedonia" from the Ottoman rule.

Several of the Macedonian revolutionaries that were instrumental in the war later became politicians of the modern Greek state. The most notable of them were the Greek writer and diplomat Ion Dragoumis and his father Stephanos Dragoumis, a judge who became Prime Minister of Greece in 1909. The Dragoumis family had a long history of participation in the Greek revolutions with Markos Dragoumis (1770-1854) being a member of Filiki Eteria in 1821.

Heroic stories from the Macedonian Struggle were documented in the novels of the Greek writer Penelope Delta in many of her books, from narratives collected in 1932-1935 by her secretary Antigone Bellou Threpsiadi, who was herself a daughter of a Macedonian fighter. Ion Dragoumis also wrote about his personal recollections of the Macedonian Struggle in his books.

After the hostilities ended, the greater Macedonia region was divided between Greece, Bulgaria and Serbia with mixed populations on every side of the borders. In 1923, after the Greek defeat in the Greco-Turkish War and the the forced population exchange, a great number of refugees from Turkey arrived in the Greek part, mixing with the local Greek inhabitants. In the coming years the national reinforcement policy effectively homogenized Macedonians with settlers from other places. Today, descendants of these settlers self-identify also as Macedonian in a regional sense and Greeks in the ethnic sense.

The last acts in the formation of the present-day demographics of Macedonia were played after World War II; the extermination of the Jews of Thessaloniki in the holocaust effectively made the Macedonian Greeks the overwhelming majority population of the city. The Greek Civil War and immigration that followed World War II were the large major factors altering the demographics, as many of the remaining Macedonian Slavs left the region. Macedonian emigration, like elsewhere in Greece, was largely towards Canada,Germany and Australia, where the Macedonian Greek community is now numerous and active.

Macedonians during World War II

Main article: Greek ResistanceMacedonians were active in the Greek resistance during Axis Occupation of Greece in the period 1941-1944. Both the first president Evripidis Bakirtzis (1895 - 1947) and the second president Alexandros Svolos (1892 - 1956) of the Political Committee of National Liberation — an opposition government separate to the royal government-in-exile of Greece — were Macedonians.

| This section needs expansion with: Macedonians-related information from the main article and other sources. You can help by adding to it. (May 2009) |

Contemporary Macedonians

Expressions of regional identity

The identity of modern Greeks from the region of Macedonia has significant connotations in the context of the Macedonia naming dispute. The dispute is over the moral right to the uses of the name Macedonia and Macedonian; it was originally between Greece, Yugoslavia and partly Bulgaria. Specifically it was targeted to the notions of Macedonians and Macedonian language with a non-Greek qualification, as used by the Socialist Republic of Macedonia during the times of socialist Yugoslavia. Macedonian Greeks were objecting to that, originally fearing territorial claims as they were noted by the U.S. Roosevelt administration through Edward Stettinius in 1944. This dispute continued to be a source of controversy between the Macedonian Greeks and Yugoslavs during the 1980s, reported in Greek press articles and through actions of the Greek government of Andreas Papandreou until the Revolutions of 1989 in Europe.

The dispute achieved international status after the breakup of Yugoslavia when the concerns of the Macedonian Greeks rose to extreme manifestations. About one million of Greeks from Macedonia participated in the 1992 Rally for Greek Macedonia (Greek:"Συλλαλητήριο για τη Μακεδονία"), a very large demonstration that took place in the streets of Thessaloniki in 1992. The point of the rally was to object to "Macedonia" being a part of the name of then newly established Republic of Macedonia using the slogan "Macedonia is Greek". In a following major rally in Australia, held in Melbourne in 1994, organized by the Macedonian Greek Australian diaspora that has significant presence there, about 100,000 people protested.

Explicit self-identification as Macedonian is a typical attitude, and a matter of national pride for many Greeks. Responding to issues around the Macedonia name dispute, the Prime minister of Greece Kostas Karamanlis — in a characteristic expression of that attitude — was quoted saying in emphasis "I myself am a Macedonian, just as 2.5 million Greeks are Macedonians" at a meeting of the Council of Europe in Strasbourg in January 2007. Both Kostas Karamanlis and the late former prime minister of Greece Konstantinos Karamanlis (his uncle), are Macedonian ethnic Greeks with origin from Serres, Eastern Macedonia. Konstantinos Karamanlis had also expressed his strong sentiments regarding the Macedonian regional identity when he was President of Greece

Political representation

Though there is no party representing specific regions of Greece - including Macedonia - May 2009 saw the formation of the 'Panhellenic Macedonian Front' coalition to run with 22 candidates in the June 2009 European Parliamentary elections . The party included Macedonian organisations of the Greek diaspora and was established by the politician Stelios Papathemelis and professor Kostas Zouraris.

Macedonian diaspora organisations

Society of Kastorians ‘Omonoia’, founded 1910; promotes Greek-American relations; assists in bettering conditions in Kastoria; maintains scholarships and hospitalization funds; operates a clubhouse. Publicatons: Kastoriana Nea, bimonthly.

Pan-Macedonian Association, founded 1947, including 15 US and Canadian regional groups (in 1993). US and Canadian citizens and residents who emigrated from Macedonia and descendants of such persons. Works to advance cultural and friendly relations between the American and Greek peoples; promotes the social welfare and educational advancement of the inhabitans of Macedonia, collect and distribute information on the land and people of Macedonia through cultural exchange between Greece and the US. Maintains a rich library (over 3,000 volumes), bestows awards. Publications: Convention Journal (annual); Macedonia (in English and Greek, quarterly).

The Macedonian Society of Great Britain (MSGB), a not for profit organisation, registered as a charity in the UK, founded in London in 1989 by Macedonian members of the Greek community. It aims to be the focal point for Macedonian Greeks and organizes social and cultural events aiming to promote the history and culture of Greece's province of Macedonia and of Greece in general. MSGB past events included leading authorities in their fields.

Pan-Macedonian Federation of Australia (Pan-Makhedoniki) is the most prominent of all the Greek Macedonian organizations in Australia. Its main establishment is in Melbourne, where the non-profit organisation of "The Pan-Macedonian Association of Melbourne and Victoria" was established in 1961 while outside Victoria the federation is active in New South Wales, Queensland, South Australia and Western Australia.

Publication. Makedoniki Zoe (Macedonian Life), monthly journal, Greek with some English articles, founded 1965, published in Thessaloniki; contains section on the diaspora, “Reports and news on the diaspora Macedonians”.

Language

The overwhelming majority of Macedonians inside Greek Macedonia speak modern Greek with small variations. The Macedonian (Greek:Μακεδονίτικα) or Thessalonian (Greek:Θεσσαλονικιώτικα) dialect belongs to the northern dialect group, with phonological and a few syntactical differences distinguishing it from standard and southern Greek. There is also a minority of Slavic-speakers that predominantly self-identifies as Greek Macedonians; it is found mainly in West Macedonia.

Famous Macedonians & Trivia

See also: List of Macedonians (Greek)- Zorba the Greek fictionalized protagonist of the novel by Nikos Kazantzakis, was the Macedonian George Zorbas (1867–1942)

- The Eurobasket 1987 champion Panagiotis Fasoulas, became the first Macedonian mayor of Piraeus.

- Τhe Greek national team that won the Eurobasket 2005 championship composed of many Macedonian players, with Dimitris Diamantidis named European Player of the Year in 2007.

- Μany Greek Olympic medalists are Macedonians: Voula Patoulidou (Barcelona 1992, golden medal), Ioannis Melissanidis (Atlanta 1996, golden medal), Dimosthenis Tampakos (Athens 2004, golden medal), Alexandros Nikolaidis (Athens 2004 silver medal)

- Theodoros Zagorakis was the captain of the 2004 Greece national football team that won the UEFA Euro 2004 champion, is now president of the Macedonian Greek football team PAOK FC. Other Macedonians in the Euro 2004 team included the goal scorers Traianos Dellas and Angelos Charisteas.

- Greek rebetika songs composer Manolis Chiotis (1920-1970) and composer & lyricist Stavros Koujioumtzis (1932-2005) were both Macedonians, born in Thessaloniki.

- Two Macedonians were lead singers at the Athens 2004 Olympics, namely Marinella and Dionysis Savvopoulos.

- Katia Dandoulaki is the first Macedonian and one of few Greek actresses to became an Academy Award nominee.

- Katia Zygouli model with appearances in international covers is Greek from Macedonia.

- Patrick Tatopoulos movie production designer and is a French-Greek with Macedonian descent on his father's side.

See also

- List of Macedonians (Greek)

- Byzantine Greeks

- Demographic history of Macedonia

- Macedonia (Greece)

- Macedonia (terminology)

- Macedonia naming dispute

References

- ^ Jupp, J. The Australian People: An Encyclopedia of the Nation, Its People and Their Origins, Cambridge University Press, October 1, 2001. ISBN 0-521-80789-1, p. 147.

- Vakalopoulos, Apostolos E. "History of Macedonia 1354-1833", Vanias Press (1984)

- ^ Pg.130Emmanuel Amand de Mendieta, Michael R. Bruce. "Mount Athos". Arbeitsgemeinschaft mit Hakkert, Amsterdam, 1972. Retrieved 2009-04-24.

- In Greek "The Cultural Identity of Greeks in Pelagonia (1912-1930)" Nikolaos Vassiliadis, Aristoteles University of Thessaloniki, 2004, p.230

- Pg.699Trudy Ring, Robert M. Salkin, Sharon La. "International Dictionary of Historic Places". Taylor & Francis. Retrieved 2009-04-24.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Pg 29,32,39 Varban N. Todorov. "Greek federalism during the nineteenth century". East European Quarterly, 1995. Retrieved 2009-04-24.

- ^ Institute for Balkan Studies. "Why wars widen". Society for Macedonian Studies, 1976. Retrieved 2009-04-24.

- ^ Pg.49,50Institute for Balkan Studies. "Why wars widen". Society for Macedonian Studies, 1976. Retrieved 2009-04-24.

- Stacy Bergstrom Haldi. "Why wars widen". Routledge. Retrieved 2009-04-24.

- Kozani.net, Kozani Greek newsblog (in Greek)

- Marii︠a︡ Nikolaeva Todorova. "Balkan identities". C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. Retrieved 2009-04-21.

- ^ Peter A. Mackridge, Eleni Yannakakis (1997). "Ourselves and others". Berg Publishers. Retrieved 2009-04-21.

- Quote "a possible cloak for aggressive intentions against Greece" ,from Wikiquote

- ^ RADIO FREE EUROPE Archive

- ^ Pg.32 Victor Roudometof (2002). "Collective memory, national identity, and ethnic conflict". Greenwood Publishing Group. Retrieved 2009-04-21.

- Eurocentrique Column, New Europe - the European weekly Issue 802 (6 October 2008). "Macedonia enlarged,". New Europe. Retrieved 2009-05-07.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Shayne Mooney, head of SBS news in Melbourne, TV coverage of the Greek Macedonian Rally in Melbourne in 1994

- Floudas, Demetrius Andreas; ""A Name for a Conflict or a Conflict for a Name? An Analysis of Greece's Dispute with FYROM",". 24 (1996) Journal of Political and Military Sociology, 285. Retrieved 2008-02-11.

- Foreign Ministry spokesman G. Koumoutsakos quoting K.Karamanlis

- Encyclopedia of Associations, official US publication of registered associations in the United States, Washington 1993

- Encyclopedia of Associations, official US publication of registered associations in the United States, Washington 1993

- Jupp, J. The Australian People: An Encyclopedia of the Nation, Its People and Their Origins, Cambridge University Press, October 1, 2001. ISBN 0-521-80789-1, p.418.

- Studies in Greek Syntax (1999), Pg 98-99 Artemis Alexiadou, Geoffrey C. Horrocks, Melita Stavrou. "Preview in Google Books".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)