| Revision as of 04:42, 2 November 2009 editAetiologic (talk | contribs)30 editsNo edit summary← Previous edit | Revision as of 05:07, 2 November 2009 edit undoAetiologic (talk | contribs)30 edits →TherapyNext edit → | ||

| Line 96: | Line 96: | ||

| ==Therapy== | ==Therapy== | ||

| Surgery remains the front-line therapy for |

Surgery remains the front-line therapy for Lynch-associated neoplasms. There is an ongoing controversy over the benefit of ]-based adjuvant therapies for HNPCC-related colorectal tumours, particularly those in stages I and II.<ref>Boland CR, Koi M, Chang DK, Carethers JM. ''The biochemical basis of microsatellite instability and abnormal immunohistochemistry and clinical behavior in Lynch Syndrome: from bench to bedside.'' Familial Cancer epub 2007; DOI 10.1007/s10689-007-9145-9</ref> | ||

| After reporting a null finding from their randomized controlled trial of aspirin (ASA) to prevent against the colorectal neoplasia of Lynch Syndrome, <ref>{{Cite journal | After reporting a null finding from their randomized controlled trial of aspirin (ASA) to prevent against the colorectal neoplasia of Lynch Syndrome, <ref>{{Cite journal | ||

Revision as of 05:07, 2 November 2009

Medical condition| Lynch syndrome |

|---|

Lynch Syndrome is a form in heritable cancer risk, characterized by a risk of several cancers including those of the endometrium, ovary, stomach, small intestine, hepatobiliary tract, upper urinary tract, brain, and skin. The increased risk for these cancers is due to inherited mutations that impair DNA mismatch repair.

The name Lynch syndrome has come to take precedence over the previously used Hereditary_nonpolyposis_colorectal_cancer. The name recognizes the contributions of Henry T. Lynch, professor of medicine at Creighton University Medical Center. It is divided into Lynch syndrome I (familial colon cancer) and Lynch syndrome II (colorectal cancer and another type of cancer, usually, but not limited to, the gastrointestinal system or the reproductive system).

Epidemiology

In the United States, about 160,000 new cases of colorectal cancer are diagnosed each year. Lynch Syndrome expressed as colorectal cancer is responsible for approximately 2 percent to 7 percent of all diagnosed cases of colorectal cancer. The average age of diagnosis of cancer in patients with this syndrome is 44 years old, as compared to 64 years old in people without the syndrome.

Cause

Lynch Syndrome arises because of defects in DNA mismatch repair lead to microsatellite instability, also known as MSI-H, which is a hallmark of HNPCC. MSI is identifiable in cancer specimens in the pathology laboratory.

Genetics

Lynch Syndrome is known to be associated with mutations in genes involved in the DNA mismatch repair pathway

| Genes implicated in Lynch Syndrome | Frequency of mutations in Lynch families | First publication

. |

|---|---|---|

| MLH1 | Together with MSH2, 90% of mutations in Lynch families. The human mutL homologue hMLH1 is located at chromosome 3p21 | Papadopoulos et al., 1994 |

| MSH2 | Together with MLH1, 90% of mutations in Lycn families.hMSH2 is gene is located at chromosome 2p21. | Fishel et al., 1993 |

| MSH6 | 7-10% of mutations in Lynch families | |

| PMS1 | <5% of mutations in Lynch families | |

| PMS2 | <5% of mutations in Lynch families |

Up to 39% of families with mutations in an Lynch-related gene do not meet the Amsterdam criteria. Therefore, families found to have a deleterious mutation in an Lynch-related gene should be considered to have Lynch Syndrome regardless of the extent of the family history. This also means that the Amsterdam criteria fail to identify many patients at risk for Lynch syndrome. Improving the criteria for screening is an active area of research, as detailed in the Screening Strategies section of this article.

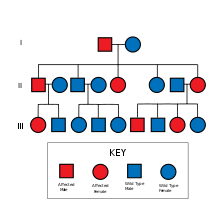

Lynch is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner. Most people with Lynch inherit the condition from a parent. However, due to incomplete penetrance, variable age of cancer diagnosis, cancer risk reduction, or early death, not all patients with a Lynch-Syndrome relate gene mutations have a parent who had cancer. Some patients develop Lynch Syndrome mutations de-novo in a new generation, without inheriting the gene. These patients are often only identified after developing an early-life colon cancer. Parents with Lynch Syndrome have a 50% chance to pass the gene on to each child.

Classification

Three major groups of MSI-H cancers can be recognized by histopathological criteria:

- (1) right-sided poorly differentiated cancers

- (2) right-sided mucinous cancers

- (3) adenocarcinomas in any location showing any measurable level of intraepithelial lymphocyte (TIL)

Risk of colon cancer

Individuals with Lynch have about an 80% lifetime risk for colon cancer. Two-thirds of these cancers occur in the proximal colon. The mean age of colorectal cancer diagnosis is 44 for members of families that meet the Amsterdam criteria. Also, women with Lynch have a 30-50% lifetime risk of endometrial cancer. The average age of diagnosis of endometrial cancer is about 46 years. Among women with Lynch who have both colon and endometrial cancer, about half present first with endometrial cancer. In Lynch, the mean age of diagnosis of gastric cancer is 56 years of age with intestinal-type adenocarcinoma being the most commonly reported pathology. Lynch-associated ovarian cancers have an average age of diagnosis of 42.5 years-old; approximately 30% are diagnosed before age 40 years. Other Lynch-Syndrome-related cancers have been reported with specific features: the urinary tract cancers are transitional carcinoma of the ureter and renal pelvis; small bowel cancers occur most commonly in the duodenum and jejunum; the central nervous system tumor most often seen is glioblastoma.

Screening

Genetic testing for mutations in DNA mismatch repair genes is expensive and time-consuming, so researchers have proposed techniques for identifying cancer patients who are most likely to be Lynch Syndrome carriers as ideal candidates for genetic testing. The Amsterdam Criteria (see below) are useful, but do not identify up to 30% of potential Lynch syndrome carriers. In colon cancer patients, pathologists can measure microsatellite instability in colon tumor specimens, which is a surrogate marker for DNA mismatch repair gene dysfunction. If there is microsatellite instability identified, there is a higher likelihood for a Lynch syndrome diagnosis. Recently, researchers combined microsatellite instability (MSI) profiling and immunohistochemistry testing for DNA mismatch repair gene expression and identified an extra 32% of Lynch syndrome carriers who would have been missed on MSI profiling alone. Currently, this combined immunohistochemistry and MSI profiling strategy is the most advanced way of identifying candidates for genetic testing for the Lynch syndrome.

Genetic counseling and genetic testing are recommended for families that meet the Amsterdam criteria, preferably before the onset of colon cancer.

Amsterdam criteria

The following are the Amsterdam criteria in identifying high-risk candidates for molecular genetic testing:

Amsterdam Criteria:

- Three or more family members with a confirmed diagnosis of colorectal cancer, one of whom is a first degree (parent, child, sibling) relative of the other two

- Two successive affected generations

- One or more colon cancers diagnosed under age 50 years

- Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) has been excluded

Amsterdam Criteria II:

- Three or more family members with HNPCC-related cancers, one of whom is a first degree relative of the other two

- Two successive affected generations

- One or more of the HNPCC-related cancers diagnosed under age 50 years

- Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) has been excluded

Diagnosis

While the "Amsterdam Clinical Criteria" have been used to identify individuals and families with a high likelihood of Lynch Syndrome, this approach identifies risk, but does not identify carriers of the defective genes. Moreover, the Amsterdam Clinical Criteria will not be useful (that is, sensitive and specific) where extended family histories are unavailable, or where there are a small number of individuals in the family tree. genetic testing for the defective genes which cause micro-satellite instability is the definitive path to a diagnosis of Lynch syndrome. Genetic testing is commercially available and is conducted through a blood test. The importance of testing should not be under-estimated as it may inform treatment options, and alter how siblings, other relatives, and children are screened and treated. Reflecting the importance of determining if the patient has MSI (and thus Lynch) and the association of Lynch with early onset colorectal neoplasia, British Columbia, Canada, ensures that all cases of bowel cancer occurring in those aged less than 50 years automatically undergo testing for Lynch Syndrome genes. .

Therapy

Surgery remains the front-line therapy for Lynch-associated neoplasms. There is an ongoing controversy over the benefit of 5-fluorouracil-based adjuvant therapies for HNPCC-related colorectal tumours, particularly those in stages I and II.

After reporting a null finding from their randomized controlled trial of aspirin (ASA) to prevent against the colorectal neoplasia of Lynch Syndrome, Burn and colleagues have recently reported new data, representing a longer follow-up period than reported in the initial NEJM paper. These new data demonstrates a reduced incidence in Lynch Syndrome patients who were exposed to at least four years of high-dose aspirin, with a satisfactory risk profile.. These results have been widely covered in the media; future studies will look at modifying (lowering) the dose (to reduce risk associated with the high dosage of ASA. Individuals with Lynch Syndrome may wish to discuss the application of these results with their medical care team.

References

- School of Medicine :: Hereditary Cancer Center :: Creighton University

- Cancer Information, Research, and Treatment for all Types of Cancer | OncoLink

- Pathology of Hereditary Nonpolyposis Colorectal Cancer - JASS 910 (1): 62 - Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences

- Papadopoulos N, Nicolaides N, Wei Y, Ruben S, Carter K, Rosen C, Haseltine W, Fleischmann R, Fraser C, Adams M (1994). "Mutation of a mutL homolog in hereditary colon cancer". Science. 263 (5153): 1625–9. doi:10.1126/science.8128251. PMID 8128251.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Fishel R, Lescoe M, Rao M, Copeland N, Jenkins N, Garber J, Kane M, Kolodner R (1993). "The human mutator gene homolog MSH2 and its association with hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer". Cell. 75 (5): 1027–38. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(93)90546-3. PMID 8252616.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Vasen HF, Watson P, Mecklin JP, Lynch HT. New clinical criteria for hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC, Lynch syndrome) proposed by the International Collaborative group on HNPCC. Gastroenterology 1999;116:1453-6. PMID 10348829.

- "Hereditary Colorectal Cancer (Lynch syndrome/HNPCC) : BC Cancer Agency". Retrieved 2009-11-02.

- Boland CR, Koi M, Chang DK, Carethers JM. The biochemical basis of microsatellite instability and abnormal immunohistochemistry and clinical behavior in Lynch Syndrome: from bench to bedside. Familial Cancer epub 2007; DOI 10.1007/s10689-007-9145-9

- Burn, John (2008-12-11). "Effect of aspirin or resistant starch on colorectal neoplasia in the Lynch syndrome". The New England Journal of Medicine. 359 (24): 2567–2578. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0801297. ISSN 1533-4406. Retrieved 2009-11-02.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - "Aspirin protects against colorectal cancer - Ecco". Retrieved 2009-11-02.

External links

- FAQs on HNPCC from the National Institute of Health

- hnpcc at NIH/UW GeneTests

- Lynch Syndrome Reading List by Dr. Kubin

- Lynch Syndrome Awareness/Fundraising by Selena Martinez

- National Cancer Institute: Genetics of Colorectal Cancer information summary

| Metabolic disease: DNA replication and DNA repair-deficiency disorder | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA replication |

| ||||||||

| DNA repair |

| ||||||||