| Revision as of 19:15, 7 November 2009 view sourceIoannes Pragensis (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users7,586 edits rv, see the discussion page← Previous edit | Revision as of 00:31, 8 November 2009 view source Bobisbob2 (talk | contribs)1,354 edits see talk pageNext edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{For|the common communist ideological stream of Bolshevism developed by ] and subsequent adherant communist governments to Bolshevism|Bolshevik|Marxism-Leninism}} | |||

| {{sprotected2}} | |||

| {{Communism sidebar |expanded=all}} | {{Communism sidebar |expanded=all}} | ||

| {{sprotected2}} | |||

| '''Communism''' (from {{lang-fr|commun}} = "common"<ref>{{cite encyclopedia | |||

| | title = Communism | |||

| | encyclopedia = Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary | |||

| | publisher = Merriam-Webster Online | |||

| | date = 2009 | |||

| | accessdate = 2009-10-04 | |||

| | url=http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/communism}}</ref>) is a family of economic and political ideas and ]s related to the establishment of an ], ] and ] based on ] and control of the ] and property in general, as well as the name given to such a society.<ref>{{cite book |last=Morris |first=William |authorlink=William Morris |title=News from nowhere |url=http://www.marxists.org/archive/morris/works/1890/nowhere/index.htm|accessdate=January 2008}}</ref><ref name="columbia">{{cite encyclopedia |title=Communism |url=http://www.bartleby.com/65/co/communism.html |encyclopedia=] |edition=6th |year=2007}}</ref><ref name="encarta">{{cite encyclopedia |last=Colton |first=Timothy J. |title=Communism |url=http://encarta.msn.com/encyclopedia_761572241/Communism.html |encyclopedia=Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia |year=2007}}</ref> As an ideology, communism is defined as "the doctrine of the conditions of the liberation of the proletariat".<ref>http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1847/11/prin-com.htm</ref> The term "Communism", when spelled with a capital letter ''C'', however, refers to any ] or political party that declares allegiance to ] or a derivative thereof and explicitly identifies itself as Communist, even if that party or state is committed to ] economic policies; as is the case with the modern ]. | |||

| '''Communism''' is a ] structure and ] that promotes the establishment of an ], ], ] based on ] and control of the ] and property in general.<ref>{{cite book |last=Morris |first=William |authorlink=William Morris |title=News from nowhere |url=http://www.marxists.org/archive/morris/works/1890/nowhere/index.htm |accessdate=January 2008}}</ref><ref name="columbia"/><ref name="encarta">{{cite encyclopedia |last=Colton |first=Timothy J. |title=Communism |url=http://encarta.msn.com/encyclopedia_761572241/Communism.html |encyclopedia=Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia |year=2007|archiveurl=http://www.webcitation.org/5kwRDfaqs|archivedate=2009-10-31|deadurl=yes}}</ref> ] posited that communism would be the final stage in ], which would be achieved through a ]. "Pure communism" in the Marxian sense refers to a classless, stateless and oppression-free society where decisions on what to produce and what policies to pursue are made ], allowing every member of society to participate in the ] in both the political and economic spheres of life. | |||

| Forerunners of communist ideas existed in antiquity and particularly in the 18th and early 19th century ], with thinkers such as ] and the more radical ]. Radical egalitarianism then emerged as a significant political power in the first half of 19th century in Western Europe. In the world shaped by the ] and the ], the newly established ] included many various political and intellectual movements, which are the direct ancestors of today's communism and ] – these two then newly minted words were almost interchangeable at the time – and of ] or ]. | |||

| As a political ideology, communism is usually considered to be a branch of ]; a broad group of economic and ] that draw on the various political and intellectual movements with origins in the work of | |||

| The two most influential theoreticians of communism of the 19th century were Germans ] and ], authors of '']'' (1848), who also helped to form the first openly communist political organisations and firmly tied communism with the idea of ] conducted by the ] ] (or the working class). Marx posited that communism would be the final stage in human society, which would be achieved after an intermediate stage called ], and through the temporary and revolutionary ]. | |||

| theorists of the ] and the ].<ref>"Socialism." Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia. ]. 03 Feb. 2008.<reference.com http://www.reference.com/browse/columbia/socialis>.</ref> Communism attempts to offer an alternative to the ] with the ] ] and the legacy of ] and ]. Marx states that the only way to solve these problems is for the working class (proletariat), who according to Marx are the main producers of wealth in society and are exploited by the Capitalist-class (]), to replace the bourgeoisie as the ruling class in order to establish a ], without class or racial divisions.<ref name="columbia"/> The dominant forms of communism, such as ], ], ] and ] are based on ], but non-Marxist versions of communism (such as ] and ]) also exist. | |||

| Karl Marx never provided a detailed description as to how communism would function as an economic system, but it is understood that a communist economy would consist of common ownership of the means of production, culminating in the negation of the concept of ] of capital, which referred to the means of production in Marxian terminology. | |||

| Communism in the ] sense refers to a classless, stateless, and oppression-free society where decisions on what to produce and what policies to pursue are made ], allowing every member of society to participate in the decision-making process in both the political and economic spheres of life. Some "]" Marxists of the following generations, henceforth known as ] or ], have slowly drifted away from the revolutionary views of Marx, instead arguing for a gradual parliamentary road to socialism; other communists, such as ] and ], continued to agitate and argue for ]. | |||

| In modern usage, communism is often used to refer to ] or ] and the policies of the various ] who had government ownership of all the means of production and ]. Communist regimes have historically been authoritarian, repressive, and coercive governments concerned primarily with preserving their own power.<ref name="encarta"/> | |||

| The ], led by Vladimir Lenin, were brought to power by the ], where the ] regime disrupted by ] was smashed by the world's first workers revolution. After years of ] (1917–1921), international isolation, erosion of the ] (workers and peasants' councils) and internal struggle within the Bolshevik leadership, the ] was founded (1922). Lenin died after a second stroke in 1924, and despite of his warnings was succeeded by ]. | |||

| ==Terminology== | |||

| Once in power, Stalin carried out multiple ] of dissidents and ]/], particularly of those around ], and established the character of Communism as the totalitarian ideology it is most commonly known as and referred to today. The Soviet Union emerged as a new global ] on the victorious side of ]. In the five years after the World War, Communist regimes were established in many states of ] and in ]. Communism began to spread its influence in the ] while continuing to be a significant political force in many Western countries. | |||

| {{Split section| List of communist ideologies|date=October 2009}} | |||

| In the schema of ], communism is the idea of a free society with no division or alienation, where mankind is free from oppression and scarcity. A communist society would have no governments, countries, or class divisions. In ], the ] is the intermediate system between capitalism and communism, when the government is in the process of changing the means of ownership from ], to collective ownership.<ref> {{cite web |title=Critique of the Gotha Programme--IV |work=Critique of the Gotha Programme |url=http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1875/gotha/ch04.htm |accessdate=2009-10-18}}</ref> | |||

| In ], the term "communism" is sometimes used to refer to ]s, a ] in which the ] operates under a ] and declares allegiance to ] or a derivative thereof. | |||

| ==Marxist schools of communism== | |||

| ] between the ] and the West, led by USA, quickly worsened after the end of the war and the ] began, a continuing state of conflict, tension and competition between the United States and the Soviet Union and those countries' respective allies. The "]" between West and East then divided Europe and world from the mid-1940s to the early 1990s. Despite many Communist successes like the victorious ] (1959-1975) or the ] (1961), the Communist regimes were ultimately unable to keep up with their Western rivals. People under Communist regimes showed their discontent in events like the ], ] of 1968 or Polish ] in early 1980s, most of which were ironically led by or included masses of workers. | |||

| {{quote|"To build communism it is necessary, simultaneous with the new material foundations, to build the new man and woman."| ], Marxist revolutionary <ref> A letter to Carlos Quijano, editor of ''Marcha'', a weekly published in Montevideo, Uruguay; published as "From Algiers, for Marcha: The Cuban Revolution Today" by ] on March 12, 1965</ref>}} | |||

| Self-identified communists hold a variety of views, including ], ], ], ], ], ], and various currents of ]. However, the offshoots of the ] interpretations of ] are the most well-known of these and have been a driving force in ] during most of the 20th century.<ref name="columbia">{{cite encyclopedia |title=Communism |url=http://www.bartleby.com/65/co/communism.html |encyclopedia=] |edition=6th |year=2007}}</ref> | |||

| After 1985, the last Soviet leader ] tried to implement market and democratic reforms under policies like '']'' ("restructuring") and '']'' ("transparency"). His reforms sharpened internal conflicts in the Communist regimes and quickly led to the ] and a total collapse of European Communist regimes outside of the Soviet Union, which itself dissolved two years later (]). Some Communist regimes outside of Europe have survived to this day, the most important of them being the ], whose ] attempts to introduce market reforms without western style ] and with the introduction of ]. | |||

| == |

===Marxism=== | ||

| ].]] | |||

| {{See also|History of communism}} | |||

| The ideal of egalitarian and collectivist society can be traced to antiquity. ]'s '']'' suggests collective education of children and control of possessions. ], the leader of the somewhat successful ] against the ] inspired many later revolutionaries.<ref>{{cite web | |||

| | last = Wilkerson | |||

| | first = Doxey A. | |||

| | title = An Epic Revolt | |||

| | url = http://www.trussel.com/hf/revolt.htm | |||

| | accessdate = 2008-02-13 | |||

| | publisher = from Masses & Mainstream, March, 1952, pp 53-58 | |||

| }}</ref> Some Christian teachings such as the '']'' with its advocacy of shared possessions, have been interpreted politically as the underpinning of ],<ref name="britannica">"Communism." '']''. 2006. Encyclopædia Britannica Online.</ref> and later of ]. ] writers such as ] in his treatise '']'' (1516) speculated about societies based on ] of property. | |||

| {{Main|Marxism}} | |||

| ]]] | |||

| Like other socialists, Marx and Engels sought an end to capitalism and the systems which they perceived to be responsible for the exploitation of workers. But whereas earlier socialists often favored longer-term ], Marx and Engels believed that popular revolution was all but inevitable, and the only path to the socialist state.<ref name=autogenerated1>{{cite encyclopedia |last=Colton |first=Timothy J. |title=Communism |url=http://encarta.msn.com/text_761572241___0/Communism.html |encyclopedia=Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia |year=2007|archiveurl=http://www.webcitation.org/5kwREEzvq|archivedate=2009-10-31|deadurl=yes}}</ref> | |||

| Criticism of the idea of private property continued into the ] in the 18th century, through such thinkers as ]. Later, following the upheaval of the ], communism emerged as a political doctrine.<ref> "Communism" ''A Dictionary of Sociology''. John Scott and Gordon Marshall. ] 2005. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press.</ref> ], in particular, espoused the goals of common ownership of land and total economic and political equality among citizens. | |||

| According to the Marxist argument for communism, the main characteristic of human life in ] is ]; and communism is desirable because it entails the full realization of ].<ref>Stephen Whitefield. "Communism." ''The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Politics''. Ed. Iain McLean and Alistair McMillan. ], 2003.</ref> Marx here follows ] in conceiving freedom not merely as an absence of restraints but as action with content.<ref name="mclean">McLean and McMillan, 2003.</ref> According to Marx, Communism's outlook on freedom was based on an agent, obstacle, and goal. The agent is the common/working people; the obstacles are class divisions, economic inequalities, unequal ], and ]; and the goal is the fulfillment of human needs including satisfying work, and fair share of the product.<ref>Ball and Dagger 118</ref><ref>Terence Ball and Richard Dagger. "Political Ideologies and the Democratic Ideal." ], Inc.:2006.</ref> They believed that communism allowed people to do what they want, but also put humans in such conditions and such relations with one another that they would not wish to exploit, or have any need to. Whereas for Hegel the unfolding of this ethical life in history is mainly driven by the realm of ideas, for Marx, communism emerged from material forces, particularly the development of the ].<ref name = "mclean"/> | |||

| During the early development of the ] in the first decades of 19th century, the germs of communism – together with those of socialism, Christian utopianism, ], ], and ] – differentiated and were theoretically examined. The term "communism" was probably coined by the French utopist ] for his communitarian social movement in 1839. In the following year 1840 the British leftist ] used this term for Babeuf's teachings. The word "socialism" came in use about 1840 and both terms were largely interchangeable at the time; the difference between the two terms was largely regional and cultural: In continental Europe "communism" was thought to be more radical and ] than socialism, while British revolutionaries preferred "socialism".<ref>{{cite book | |||

| | last = Williams | |||

| | first = Raymond | |||

| | title = Keywords: a vocabulary of culture and society | |||

| | publisher = Fontana | |||

| | year = 1976 | |||

| | isbn = 0006334792}}</ref> | |||

| Marxism holds that a process of ] and revolutionary struggle will result in victory for the ] and the establishment of a ] in which private ownership is abolished over time and the means of production and subsistence belong to the community. Marx himself wrote little about life under communism, giving only the most general indication as to what constituted a communist society. It is clear that it entails abundance in which there is little limit to the projects that humans may undertake.{{Citation needed|date=April 2008}} In the popular slogan that was adopted by the ], communism was a world in which each gave according to their abilities, and received according to their needs. '']'' (1845) was one of Marx's few writings to elaborate on the communist future: | |||

| ]]] | |||

| <blockquote>"In communist society, where nobody has one exclusive sphere of activity but each can become accomplished in any branch he wishes, society regulates the general production and thus makes it possible for me to do one thing today and another tomorrow, to hunt in the morning, fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, criticise after dinner, just as I have a mind, without ever becoming hunter, fisherman, herdsman or critic."<ref>Karl Marx, (1845). '']'', Marx-Engels Institute, Moscow. ISBN 978-1-57392-258-6. Sources available at at www.marxists.org.</ref> | |||

| The early socialist movement, rather undifferentiated at the time, concentrated in the most industrialised European countries. In France with its revolutionary tradition lived ], whose circle coined the term "exploitation of man by man"; ], the inventor of the word "feminism" and a propagator of communist communities; and ], author of the term "dictatorship of the proletariat", who spent most of his life in prisons for his revolutionary actions. France saw also activities of early anarchists ], who asserted that "]", and the Russian nobleman ]. | |||

| </blockquote> | |||

| Marx's lasting vision was to add this vision to a theory of how society was moving in a law-governed way toward communism, and, with some tension, a political theory that explained why revolutionary activity was required to bring it about.<ref name="mclean"/> | |||

| ]]] | |||

| In Great Britain, the ], named after the ''People's Charter'' published in 1838, demanded the equal civil right to vote for all men, including the lower classes. Among early English social reformers was the ] ], the founder of the ] movement and of the utopian community of ]. Founded in the U.S. state of Indiana in 1825, New Harmony collapsed after four years over internal quarrels, much like other similar undertakings.<ref>Muravchik, Joshua. ''Heaven on Earth: The Rise and Fall of Socialism'', Chapter 2, ISBN 978-1893554450</ref> | |||

| In the late 19th century, the terms "socialism" and "communism" were often used interchangeably. However, Marx and Engels argued that communism would not emerge from capitalism in a fully ], but would pass through a "first phase" in which most productive property was owned in common, but with some class differences remaining. The "first phase" would eventually evolve into a "higher phase" in which class differences were eliminated, and a state was no longer needed. Lenin frequently used the term "socialism" to refer to Marx and Engels' supposed "first phase" of communism and used the term "communism" interchangeably with Marx and Engels' "higher phase" of communism.<ref name="encarta"/> | |||

| Around 1850, the modern political left began to emerge in ] and in ]. ] call the period of communist theory leading to this "]", as opposed to their "]" or "scientific communism".<ref>{{cite web | |||

| | last = Engels | |||

| | first= Friedrich | |||

| | title = Socialism: Utopian and Scientific | |||

| | url = http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1880/soc-utop/index.htm | |||

| | accessdate = 2008-02-13 | |||

| | publisher = Marxists.org | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| These later aspects, particularly as developed by Lenin, provided the underpinning for the mobilizing features of 20th century Communist parties. Later writers such as ] and ] modified Marx's vision by allotting a central place to the state in the development of such societies, by arguing for a prolonged transition period of socialism prior to the attainment of full communism.{{Citation needed|date=April 2008}} | |||

| == From Marx to World War I == | |||

| === Marxism === | |||

| {{See also|Marxism|List of communist ideologies}} | |||

| {{Marxism}} | |||

| ]]] | |||

| Marxism, initially developed by German revolutionary philosophers ] and ] from 1840s into the 1890s, became the principal form of socialist thought during this time, and with few exceptions, it remained in this position well until the 1970s. Most influential leftist and ] theories either develop Marxism further (e.g., ], ], ] and ]), or completely drop Marxist ideology and do not set the creation of classless society as their aim (e.g., the modern ], ], ]). Therefore the words Marxism and communism are usually understood as synonymous. | |||

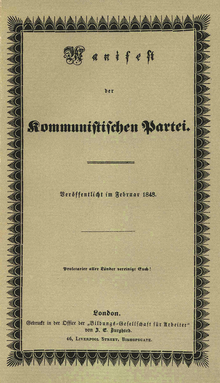

| ]'', London 1848]] | |||

| ===Marxism-Leninism=== | |||

| Marx and Engels considered ] to be a system based on relentless ] for profit, or ] as they put it, among capitalists and capitalist states. In his ], Marx argued that this becomes possible by the ] and the ] of workers. According to Marx, the main characteristic of human life in a class society is ], while communism entails the full realisation of human freedom.<ref>Stephen Whitefield. "Communism." ''The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Politics''. Ed. Iain McLean and Alistair McMillan. Oxford University Press, 2003.</ref> Marx here follows ] in conceiving freedom not merely as an absence of restraints but as action with content.<ref name="mclean">McLean and McMillan, 2003.</ref> Marx believed that communism would give people the power to appropriate the fruits of their labor while preventing them from exploiting others. Whereas for Hegel the unfolding of this ethical life in history is mainly driven by the realm of ideas, for Marx, communism emerged from material forces, particularly the development of the ].<ref name = "mclean"/> | |||

| {{Main|Marxism-Leninism}} | |||

| Marxism-Leninism is a version of socialism adopted by the Soviet Union and most Communist Parties across the world today. It shaped the Soviet Union and influenced Communist Parties worldwide. It was heralded as a possibility of building communism via a massive program of ] and ]. Historically, under the ideology of Marxism-Leninism the rapid development of industry, and above all the victory of the Soviet Union in the Second World War occurred alongside a third of the world being lead by Marxist-Leninist inspired parties. Despite the fall of the Soviet Union and Eastern Bloc countries, many communist Parties of the world today still lay claim to uphold the Marxist-Leninist banner. Marxism-Leninism expands on Marxists thoughts by bringing the theories to what Lenin and other Communists considered, the age of capitalist imperialism, and a renewed focus on party building, the development of a ], and democratic centralism as an organizational principle. | |||

| Marxists hold that due to the innate antagonism and ] between labour and capital, the inevitable process of revolutionary struggle can result in victory for the ], or the workers, and the establishment of a ] in which private ownership is abolished over time and the means of production and subsistence become the collective property of society. Marx himself wrote little about life under communism, giving only the most general indication as to what constituted a communist society. '']'' (1845) was one of Marx's few writings to elaborate on the communist future: | |||

| ====Stalinism==== | |||

| <blockquote>"In communist society, where nobody has one exclusive sphere of activity but each can become accomplished in any branch he wishes, society regulates the general production and thus makes it possible for me to do one thing today and another tomorrow, to hunt in the morning, fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, criticise after dinner, just as I have a mind, without ever becoming hunter, fisherman, herdsman or critic."<ref>Karl Marx, (1845). '']'', Marx-Engels Institute, Moscow. ISBN 978-1-57392-258-6. Sources available at </ref> | |||

| {{Main|Stalinism}} | |||

| </blockquote> | |||

| "Stalinism" refers to the ] of the ], and the countries within the Soviet ], during the leadership of Joseph Stalin. The term usually defines the style of a government rather than an ideology. The ideology was "] theory", reflecting that Stalin himself was not a theoretician, in contrast to ] and ], and prided himself on maintaining the legacy of Lenin as a founding father for the Soviet Union and the future Socialist world. Stalinism is an interpretation of their ideas, and a certain political regime claiming to apply those ideas in ways fitting the changing needs of society, as with the transition from "socialism at a snail's pace" in the mid-twenties to the rapid industrialization of the ]s. | |||

| The main contributions of Stalin to communist theory were: | |||

| In the late 19th century, the terms "socialism" and "communism" were often used interchangeably. However, Marx and Engels argued that communism would not emerge from capitalism in a fully developed state, but would pass through a lower phase in which productive property was owned in common but people would be allowed to take from the social wealth only to the extent of their contribution to the production of that wealth. As the masses of the people begin to overcome their ] and replace competition with social cooperation, this "lower phase" would eventually evolve into a "higher phase" in which the antithesis between mental and physical labour has disappeared, people enjoy their work, and goods are produced in abundance, allowing people to freely take according to their needs. Lenin frequently used the term "socialism" to refer to Marx and Engels' "lower phase" of communism and used the term "communism" interchangeably with Marx and Engels' "higher phase" of communism. | |||

| * The groundwork for the Soviet policy concerning nationalities, laid in Stalin's 1913 work ''Marxism and the National Question'',<ref></ref> praised by Lenin. | |||

| * ], | |||

| * The theory of ], a theoretical base supporting the repression of political opponents as necessary. | |||

| ====Trotskyism==== | |||

| === First international organisations === | |||

| ] reading '']''.]] | |||

| The first Marxist international organisation was the ]. It was founded originally as the ] by ] workers in ] in 1836. This was initially a ] and ] grouping devoted to the ideas of ]. The League of the Just participated in the ] uprising of May 1839 in Paris.<ref> by Bernard Moss, p.10, in the '']'', 1998 </ref> Thereafter expelled from France, the League of the Just moved to London where by 1847 numbered about 1,000. ]'s 1842 book, ''Guarantees of Harmony and Freedom'', which criticised private property and ] society, was one of the bases of its social theory. The Communist League was created in London in June 1847 out of a merger of the League of the Just and of the fifteen-man Communist Correspondence Committee of Bruxelles, headed by Karl Marx.<ref>Murray Rothbard, "Karl Marx: Communist as Religious Eschatologist," p.166 </ref> The birth conference was attended by ], who convinced the League to change its motto from ''All men are brethren''<ref>{{Cite book | |||

| {{Main|Trotskyism}} | |||

| | last = Volkov | |||

| | first = G. N. | |||

| | year = 1979 | |||

| | title = The Basics of Marxist-Leninist Theory | |||

| | publisher = Progress Publishers | |||

| | place = Moskva }} | |||

| </ref> to ]'s phrase, ''Working men of all countries, unite!''. The Communist League held a second congress, also in London, in November and December 1847. Both Marx and Engels attended, and they were mandated to draw up a manifesto for the organisation. This became the famous '']''. The League was ended formally in 1852. | |||

| Trotsky and his supporters organized into the '']'' and their platform became known as '']''. Stalin eventually succeeded in gaining control of the Soviet regime and Trotskyist attempts to remove Stalin from power resulted in Trotsky's exile from the Soviet Union in 1929. During Trotsky's exile, world communism fractured into two distinct branches: ] and ].<ref name="columbia"/> Trotsky later founded the ], a Trotskyist rival to the ], in 1938. | |||

| ] ]] | |||

| In 1864 in a workmen's meeting held in Saint Martin's Hall, London there was founded the ] (IWA), better known as the ]. It was an international ] organisation which aimed at uniting a variety of different ] political groups and ] organisations that were committed to the ] and ]. At its founding, it was an alliance of people from diverse groups, besides Marxists it included French ], ], English ], Italian ], such American proponents of ] as ] and ], followers of ], and other socialists of various persuasions. Due to the wide variety of philosophies present in the First International, there was conflict from the start. The first objections to Marx's came from the Mutualists who opposed communism and ]. However, shortly after ] and his followers (called ''Collectivists'' while in the International) joined in 1868, the First International became polarised into two camps, with Marx and Bakunin as their respective figureheads. Perhaps the clearest differences between the groups emerged over their proposed strategies for achieving their visions of socialism. The anarchists grouped around Bakunin favoured (in ]'s words) "direct economical struggle against capitalism, without interfering in the political parliamentary agitation." Marxist thinking, at that time, focused on parliamentary activity. For example, when the new ] of 1871 introduced ], many German socialists became active in the Marxist ]. | |||

| Trotskyist ideas have continually found a modest echo among ]s in some countries in ] and ], especially in ], ], ] and ]. Many Trotskyist organizations are also active in more stable, developed countries in ] and ]. Trotsky's politics differed sharply from those of Stalin and Mao, most importantly in declaring the need for an international proletarian revolution (rather than socialism in one country) and unwavering support for a true dictatorship of the proletariat based on democratic principles. | |||

| In 1872, the conflict in the First International climaxed with a final split between the two groups at the ]. This clash is often cited as the origin of the long-running ]. From then on, the ''Marxist'' and '']'' currents of socialism had distinct organisations, at various points including rival ] In 1872, the organisation was relocated to ]. The First International disbanded four years later, at the 1876 Philadelphia conference. | |||

| However, as a whole, Trotsky's theories and attitudes were never accepted in worldwide mainstream Communist circles after Trotsky's expulsion, either within or outside of the ]. This remained the case even after the ] and subsequent events critics claim exposed the fallibility of ]. | |||

| In the last years of the First International there was a short-lived but important first attempt of socialists to seize power, the ], a government that briefly ruled Paris, from March 28 to May 28, 1871. It existed before the final split between anarchists and socialists had taken place, and therefore it is hailed by both groups as the first assumption of power by the working class. Debates over the policies and outcome of the Commune contributed to the break between those two political groups. | |||

| Some criticize Trotskyism as incapable of using concrete analysis on its theories, rather resorting to phrases and abstract notions.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.marx2mao.com/Other/OT73NB.html |title=On Trotskyism |publisher=Marx2mao.com |date= |accessdate=2009-10-18}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://home.flash.net/~comvoice/32cTrotskyism.html |title=Swedish FRP on anti-Marxist-Leninist dogmas of Trotskyism |publisher=Home.flash.net |date= |accessdate=2009-10-18}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://web.archive.org/web/20080201115440/http://www.etext.org/Politics/MIM/wim/wyl/ |title=What's Your Line? |publisher=Web.archive.org |date= |accessdate=2009-10-18}}</ref> | |||

| === Second International === | |||

| The Socialist International better known as the ] (1889–1916), a Marxist organisation of ], was formed in ] on ], ] with support of Engels (Marx was already dead at the time). At the Paris meeting delegations from 20 countries participated.<ref>Rubio, José Luis. ''Las internacionales obreras en América''. ]: 1971. p. 42.</ref> The International continued the work of the dissolved ], though this time excluding the ], and was in existence until 1916. | |||

| ====Maoism==== | |||

| ] ]] | |||

| </ref>]] | |||

| Among the Second International's most famous actions were its (1889) declaration of ] as ] and its 1910 declaration of March 8 as ]. It initiated the international campaign for the ].<ref>Rubio, José Luis. ''Las internacionales obreras en América''. ]: 1971. p. 43</ref> The International's permanent executive and information body was the ] (ISB), based in ] and formed after the International's Paris Congress of 1900. ] and ] of the ] were its chair and secretary. ] was a member of the International from 1905. The Second International dissolved during ], in 1916, as the separate national parties that composed it did not maintain a ] front against the war, instead generally supporting their respective nations' role. ] (SFIO) leader ]'s assassination, a few days before the beginning of the war, symbolised the failure of the ] doctrine of the Second International. | |||

| {{Main|Maoism}} | |||

| Maoism is the Marxist-Leninist trend of Communism associated with ] and was mostly practiced within the ]. Khrushchev's reforms heightened ideological differences between the ] and the Soviet Union, which became increasingly apparent in the 1960s. As the ] in the ] turned toward open hostility, China portrayed itself as a leader of the underdeveloped world against the two superpowers, the United States and the Soviet Union.{{Citation needed|date=April 2008}} | |||

| Although mostly Marxist, this loose federation of the world’s socialist parties included both openly ] organisations that saw a gradual implementation of reforms to capitalism as the way to achieve socialism (forerunners of today's ]), and revolutionary socialist parties that saw the need to smash the capitalist state structure through a mass workers' revolution in order to create a communist society (communists in the sense of the 20th century). | |||

| Parties and groups that supported the ] (CPC) in their criticism against the new Soviet leadership proclaimed themselves as 'anti-revisionist' and denounced the CPSU and the parties aligned with it as ] "capitalist-roaders." The Sino-Soviet Split resulted in divisions amongst communist parties around the world. Notably, the ] sided with the People's Republic of China. Effectively, the CPC under Mao's leadership became the rallying forces of a parallel international Communist tendency. The ideology of CPC, Marxism-Leninism-Mao Zedong Thought (generally referred to as 'Maoism'), was adopted by many of these groups.{{Citation needed|date=April 2008}} | |||

| == Communists in power == | |||

| ], ], and ].]] | |||

| === Bolsheviks and the birth of the Soviet Union === | |||

| {{See also|Russian Revolution (1917)|History of Soviet Russia and the Soviet Union (1917–1927)}} | |||

| In Russia, the 1917 ] was the first time any mass party with an avowedly Marxist ideology, in this case the ], seized state power. The assumption of state power by the Bolshevik-led workers' ] generated some practical and theoretical debate within the Marxist movement. Marx had predicted that socialism and communism would most likely be built upon foundations laid by capitalism in the most advanced capitalist countries such as Germany and Britain. Russia, however, was at the time one of the poorest and most industrially backward countries in Europe with an enormous, largely illiterate ] and a minority of industrial workers. Marx, however, had explicitly stated that Russia might be able to skip the stage of ] capitalism.<ref>Marc Edelman, "Late Marx and the Russian road: Marx and the 'Peripheries of Capitalism'" - book reviews. ''Monthly Review'', Dec., 1984. at www.findarticles.com.</ref>, an idea further developed by ] known as the theory of ]. Other socialists also believed that a Russian revolution could be the precursor of workers' revolutions in the West, drawing on the volatile and pre-revolutionary climate in Germany, Italy and Austria. | |||

| After Mao's death and his replacement by ], the international Maoist movement diverged. One sector accepted the new leadership in China; a second renounced the new leadership and reaffirmed their commitment to Mao's legacy; and a third renounced Maoism altogether and aligned with ].{{Citation needed|date=April 2008}} | |||

| The ]s, however, opposed the Bolshevik's notion of socialist revolution before capitalism was fully developed in Russia. The Bolsheviks' successful rise to power was partially based upon their slogans of "Peace, bread, and land" and "All power to the Soviets!", slogans which tapped the massive public desire for an end to Russian involvement in the ], the peasants' demand for ], and popular support for the ]. | |||

| ====Hoxhaism==== | |||

| Once in power, the Bolsheviks immediately withdrew Russia from the ], established workers' control in the factories, legalised divorce, installed ], granted freedom and ] to national minorities, carried out major land reforms in the interest of poor peasants, initiated mass literacy campaigns, assisted the restoration of oppressed religious minorities, decriminalised ], separated the church and the state, began the task of eliminating homelessness and "freed" women from the burden of housework by setting up communal kitchens, laundries and free nurseries for children. Many of their progressive policies such as the decriminalisation of homosexuality were however reverted once Stalin assumed power. | |||

| Another variant of ] ] appeared after the ] between the ] and the ] in 1978. The Albanians rallied a new separate international tendency. This tendency would demarcate itself by a strict defense of the legacy of Joseph Stalin and fierce criticism of virtually all other Communist groupings as ]. Critical of the United States, Soviet Union, and China, ] declared the latter two to be ] and condemned the ] by withdrawing from the ] in response. Hoxha declared Albania to be the world's only Marxist-Leninist state after 1978. The Albanians were able to win over a large share of the Maoists, mainly in ] such as the ], but also had a significant ] in general. This tendency has occasionally been labeled as 'Hoxhaism' after him. | |||

| After the fall of the Communist government in Albania, the pro-Albanian parties are grouped around an ] and the publication 'Unity and Struggle'. | |||

| ] and ], common ].]] | |||

| The usage of the terms "communism" and "socialism" began to shift after 1917, when the Bolsheviks changed their name to the Communist Party and devoted the power of the state to the implementation of socialist policies, in line with what is today referred to as ]. Lenin established the ] (Comintern) in 1919 in order to unite the efforts of the world's communist parties in their fight against capitalism, and in 1920 issued the ], which included ], to all European socialist parties willing to adhere. In France, for example, the majority of the SFIO socialist party split in 1921 to form the ] (French Section of the Communist International). Henceforth, the term "Communist" was applied to the parties founded under the umbrella of the Comintern. Their program called for the uniting of workers of the world for workers' revolution, which would be followed by the establishment of a democratic and temporary ], as well as the development of a socialist economy, ultimately leading to the ] and the development of a harmonious classless society, based on cooperation instead of market competition. | |||

| ===Titoism=== | |||

| During the ] (1918–1922), the Bolsheviks ] all means of production and imposed the policy of '']'', which put factories and railroads under government control, collected and rationed food, and introduced some temporary ] management of industry. After three years of war and the 1921 ] and in light of the failure of the Russian Revolution to spread to the rest of Europe, Lenin declared the ] (NEP) in 1921, which was to give a "limited place for a limited time to capitalism." The NEP lasted until 1928, when ] seized party leadership, and the introduction of the first ] spelled the end of it. Following the Russian Civil War, the Bolsheviks formed in 1922 the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), or ], from the former ]. | |||

| {{Main|Titoism}} | |||

| Elements of Titoism are characterized by policies and practices based on the principle that in each country, the means of attaining ultimate communist goals must be dictated by the conditions of that particular country, rather than by a pattern set in another country. During Tito’s era, this specifically meant that the communist goal should be pursued independently of (and often in opposition to) the policies of the ]. | |||

| The term was originally meant as a ], and was labeled by Moscow as a heresy during the period of tensions between the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia known as the '']'' period from 1948 to 1955. | |||

| === Stalin === | |||

| A few years after Lenin's death, ] won out over his chief rival ] and in 1928 emerged as the sole leader of the ], the position he held until his death in 1953. His name is connected with ], an oppressive system of extensive government ], ], ] and political "purging", or elimination of political opponents either by direct killing or through exile. His methods involved an extensive use of ] to establish a ] around him to maintain control over the nation's people and to maintain political control for the ]. | |||

| Unlike the rest of ], which fell under ]'s influence post-World War II, ], due to the strong leadership of ] and the fact that the ] liberated Yugoslavia with only limited help from the ], remained independent from Moscow. It became the only country in the ] to resist pressure from Moscow to join the ] and remained "socialist, but independent" right up until the collapse of Soviet socialism in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Throughout his time in office, Tito prided himself on Yugoslavia's independence from Russia, with Yugoslavia never accepting full membership of the ] and Tito's open rejection of many aspects of ] as the most obvious manifestations of this. | |||

| Stalinism usually defines the style of a government rather than an ideology. The ideology was ], reflecting that Stalin prided himself on the claim of maintaining the legacy of Lenin as a founding father of the Soviet Union and the future Socialist world. Stalinism is an interpretation of their ideas, and a certain political regime claiming to apply those ideas in ways fitting the changing needs of society, as with the transition from "socialism at a snail's pace" in the mid-twenties to the rapid industrialisation of the ]s. Sometimes, although rarely, the compound terms "Marxism-Leninism-Stalinism" (used by the ]ian ]), or ''teachings of ]/]/]/]'', are used to show the alleged heritage and succession. Simultaneously, however, many ]s and ]s view Stalinism as a perversion of their ideas; ]s, in particular, are virulently anti-Stalinist, considering Stalin a counter-revolutionary. | |||

| ===Eurocommunism=== | |||

| The main contributions of Stalin to Communist theory were the groundwork for the Soviet policy concerning nationalities, laid in Stalin's 1913 work '']'',<ref></ref>, the theory of ] as a "correction" of Marx's theory of ], and the theory of "]", a theoretical base supporting the repression of political opponents. | |||

| {{Main|Eurocommunism}} | |||

| Since the early 1970s, the term ] was used to refer to moderate, reformist Communist parties in western Europe. These parties did not support the Soviet Union and denounced its policies. Such parties were politically active and electorally significant in ] (]), ] (]), and ] (]).<ref name="encarta"/> | |||

| ===Council communism=== | |||

| At the end of the 1920s Stalin launched a wave of radical, and often brutal, economic policies, which completely overhauled the industrial and agricultural face of the Soviet Union. This came to be known as the ''Great Turn'' as Russia turned away from the quasi-capitalist ]. The NEP had been implemented by Lenin in order to ensure the survival of the state following isolation and seven years of war (1914-1921, ] from 1914 to 1917, and the subsequent Civil War) and had rebuilt Soviet production to its 1913 levels. It "modernized the Soviet Union, transforming a peasant society into an industrial state with a literate population and a remarkable scientific superstructure",<ref>], collected in ''Marxism Beyond Marxism'' (1996) ISBN 0-415-91442-6, page 43</ref> but at the expenses of forced ], ] and terror.<ref name="reflections"> ] ''Reflections on a Ravaged Century'' (2000) ISBN 0-393-04818-7, page 101</ref> | |||

| {{Main|Council communism}} | |||

| Council communism is a ] movement originating in ] and the ] in the 1920s. Its primary organization was the ] (KAPD). Council communism continues today as a theoretical and activist position within both left-wing ] and ]. | |||

| The central argument of council communism, in contrast to those of ] and ] Communism, is that democratic ] arising in the factories and municipalities are the natural form of working class organisation and governmental power. This view is opposed to both the ] and the Leninist ], with their stress on, respectively, ]s and ] government (i.e., by applying social reforms), on the one hand, and ] and participative ] on the other). | |||

| === Cold War === | |||

| ], black other states) or ] definition (yellow) during ]]] | |||

| The core principle of council communism is that the ] and the ] should be managed by ] composed of ]s elected at workplaces and ] at any moment. As such, council communists oppose ] ] "]"/"]". They also oppose the idea of a "revolutionary party", since council communists believe that a revolution led by a party will necessarily produce a party dictatorship. Council communists support a worker's democracy, which they want to produce through a federation of workers' councils. Council communism (and other types of "] and ] Marxism" such as ]) are often viewed as being similar to ] because they criticize Leninist ideologies for being authoritarian and reject the idea of a vanguard party. | |||

| After ], Communists consolidated power in ], and in 1949, the ] ] (CPC) led by ] established the ], which would later follow its own ideological path of Communist development. ], ], ], ], ], ], and ] were among the other countries in the ] that adopted or imposed a pro-Communist government at some point. Although never formally unified as a single political entity, by the early 1980s almost one-third of the world's population lived in ]s, including the former ] and ]. By comparison, the ] had ruled up to one-quarter of the world's population at its greatest extent.<ref>{{cite news |last=Hildreth |first=Jeremy |title=The British Empire's Lessons for Our own |url=http://online.wsj.com/article/SB111870387824258558.html |work=] |date=2005-06-14}}</ref> | |||

| ===Luxemburgism=== | |||

| Communist states such as the Soviet Union and China succeeded in becoming industrial and technological powers, challenging the capitalists' powers in the ] and ] and in military conflicts. | |||

| {{Main|Luxemburgism}} | |||

| Luxemburgism, based on the writing of ], is an interpretation of ] which, while supporting the ], as Luxemburg did, agrees with her criticisms of the politics of ] and ]; she did not see their concept of "]" as democracy. | |||

| The chief tenets of Luxemburgism are commitment to ] and the necessity of the revolution taking place as soon as possible. In this regard, it is similar to ], but differs in that, for example, Luxemburgists don't reject ]s by principle. It resembles ] in its insistence that only relying on the people themselves as opposed to their leaders can avoid an ] society, but differs in that it sees the importance of a revolutionary party, and mainly the centrality of the ] in the revolutionary struggle. It resembles ] in its opposition to the ] of ] government while simultaneously avoiding the reformist politics of modern ], but differs from Trotskyism in arguing that Lenin and Trotsky also made undemocratic errors. | |||

| The split between Communist and capitalist worlds resulted in the ], an continuing state of conflict, tension and competition that existed primarily between the ] and the ] and those countries' respective allies from the mid-1940s to the early 1990s. Throughout this period, the conflict was expressed through military coalitions, support for various dictatorships, espionage, weapons development, invasions, propaganda, and competitive technological development, which included the ]. The conflict included costly defense spending, a massive ] and ] ], and numerous ]s; the two superpowers never fought one another directly. | |||

| Luxemburg's idea of democracy, which ] calls "''generalized'' democracy in an unarticulated form", represents Luxemburgism's greatest break with "mainstream communism", since it effectively diminishes the role of the ], but is in fact very similar to the views of ] ("''The emancipation of the working classes must be conquered by the working classes themselves''"). According to Aronowitz, the vagueness of Luxembourgian democracy is one reason for its initial difficulty in gaining widespread support. However, since the fall of the ], Luxemburgism has been seen by some socialist thinkers as a way to avoid the ] of Stalinism. Early on, Luxemburg attacked undemocratic tendencies present in the Russian Revolution: | |||

| The Soviet Union created an ] of countries that it occupied, annexing some as ] and maintaining others as ] that would later form the ]. The United States and various western European countries began a policy of "]" of Communism and forged many alliances to this end, including later ]. In the ] the Soviet Union fostered ]ary movements, which the United States and many of its allies opposed and, in some cases, attempted to "]". Many countries were prompted to align themselves with the countries that would later either form NATO or the Warsaw Pact. The Cold War saw periods of both heightened tension and relative calm as both sides sought ]. Direct military attacks on adversaries were deterred by the potential for ] using deliverable ]s. | |||

| ===Juche=== | |||

| The relations between the Soviet Union and its satellites were described by the so-called ] which was announced to justify the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in August 1968 to terminate the ], an attack similar to earlier Soviet military interventions, such as the ]. These interventions were meant to put an end to liberalisation efforts and uprisings that had the potential to compromise Soviet hegemony inside the ], which was considered by the Soviets to be an essential defensive and strategic buffer in case hostilities with the West were to break out. It meant that limited independence of Communist parties was allowed, but no country would be allowed to leave the ], disturb a nation's Communist party's monopoly on power, or in any way compromise the strength of the Eastern Bloc. Implicit in this doctrine was that the leadership of the Soviet Union reserved, for itself, the right to define "socialism" and "capitalism". The principles of the doctrine were so broad that the Soviet Union even used it to justify its military intervention in the non-Warsaw Pact nation of ]. | |||

| {{Unreferenced section|date=November 2008}} | |||

| {{Main|Juche}} | |||

| In 1992, ] replaced ] in the revised North Korean constitution as the official state ideology, this being a response to the ]. Juche was originally defined as a creative application of Marxism-Leninism, but after the 1991 collapse of the ] (North Korea’s greatest economic benefactor), all reference to Marxism-Leninism was dropped in the revised 1998 constitution. The establishment of the ] doctrine in the mid-1990s has formally designated the ], not the ] or ], as the main revolutionary force in North Korea. All reference to communism had been dropped in the 2009 revised constitution.<ref>http://www.reuters.com/article/latestCrisis/idUSSEO253213</ref> | |||

| According to Kim Jong-il's ''On the Juche Idea'', the application of Juche in state policy entails the following: | |||

| === Crisis === | |||

| # The people must have independence (''chajusong'') in thought and ], economic ], and self-reliance in defense. | |||

| The Cold War drew to a close in the late 1980s and the early 1990s. The United States under President ] increased diplomatic, military, and economic pressure on the Soviet Union, which was already suffering from ]. In the second half of the 1980s, newly appointed Soviet leader ] introduced the '']'' and '']'' reforms. | |||

| # Policy must reflect the will and aspirations of the masses and employ them fully in revolution and construction. | |||

| # Methods of revolution and construction must be suitable to the situation of the country. | |||

| # The most important work of revolution and construction is molding people ideologically as communists and mobilizing them to constructive action. | |||

| ===Prachandapath=== | |||

| ] | |||

| ], giving a speech at the Nepalese city of ].]] | |||

| {{Main|Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist)}} | |||

| Prachanda Path refers to the ideological line of the ]. This thought doesn't make an ideological break with ],] and ] but it is an extension of these ideologies totally based on home-ground politics of ]. The doctrine came into existence after it was realized that the ideology of Marxism, Leninism and Maoism couldn't be practiced completely as it were done in the past. And an ideology suitable, based on the ground reality of Nepalese politics was adopted by the party. | |||

| After five years of armed struggle, the party realized that none of the proletarian revolutions of the past could be carried out on Nepal’s context. So moving further ahead than Marxism, Leninism and Maoism, the party determined its own ideology, Prachanda Path. | |||

| The weakening of the central power enabled ], sometimes called the "Autumn of Nations",<ref>See various uses of this term in . The term is a play on a more widely used term for 1848 revolutions, the ].</ref> a ] that swept across ] and ] in late 1989, ending in the overthrow of ]-style ]s within the space of a few months.<ref name="Szafarz-221">E. Szafarz, "The Legal Framework for Political Cooperation in Europe" in ''The Changing Political Structure of Europe: Aspects of International Law'', Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 0-7923-1379-8. .</ref> | |||

| Having analyzed the serious challenges and growing changes in the ], the party started moving on its own doctrine. Prachanda Path in essence is a different kind of uprising, which can be described as the fusion of a protracted people’s war strategy which was adopted by ] in China and the Russian model of armed revolution. Most of the Maoist leaders think that the adoption of Prachanda Path after the second national conference is what nudged the party into moving ahead with a clear vision ahead after five years of ‘people’s war’. | |||

| The political upheaval began in ],<ref>] and ], "Independence Reborn and the Demons of the Velvet Revolution" in ''Between Past and Future: The Revolutions of 1989 and Their Aftermath'', Central European University Press. ISBN 963-9116-71-8. .</ref> continued in ], and then led to a surge of mostly peaceful revolutions in ], ], and ]. ] was the only ] country to overthrow its Communist regime violently and execute its head of state.<ref>], preface to ''Society in Action: the Theory of Social Becoming'', ]. ISBN 0-226-78815-6. .</ref> | |||

| Senior Maoist leader Mohan Vaidya alias Kiran says, ‘Just as Marxism was born in Germany, Leninism in Russia and Maoism in China and Prachanda Path is Nepal’s identity of revolution. Just as Marxism has three facets- philosophy, ] and scientific socialism, Prachanda Path is a combination of all three totally in Nepal’s political context.’ Talking about the party’s philosophy, Maoist chairman ] says, ‘The party considers Prachanda path as an enrichment of Marxism, Leninism and Maoism.’ After the party brought forward its new doctrine, the government was trying to comprehend the new ideology, Prachanda Path. | |||

| The Revolutions of 1989 greatly altered the ] in the world and marked (together with the subsequent ]) the end of the ] and the beginning of the ]. ] in 1991, leaving the United States as the dominant military power, though ] retained much of the massive Soviet nuclear arsenal. | |||

| ''see also: ]'' | |||

| == Current situation == | |||

| The communist ideology in its Marxist stream is still alive and well. ] amongst other Marxists continue to describe themselves as socialist and communist interchangeably. Many of them hold that since the Soviet Union after the rise of Stalin to power was nothing more than a ] country, its demise means nothing more than the failure of one style of capitalist economic organisation. Although small in numbers, Marxist socialists and communists continue to build their ranks in many countries such as the ] (SWP) in Britain, ] (ISO) in the US and the ] in ]. | |||

| ==Non-Marxist schools== | |||

| ] stream of thought on the other hand has been damaged and further discredited by the collapse of the Soviet Union. This has meant that many Communist parties worldwide have lost mass membership and shifted to the right, adopting ] and free market politics. Some Communist states such as the People's Republic of China and other Asian Communist states and Cuba, though have proven resistant. The Chinese version of reforms concentrated on support of market forces while effectively prohibiting Western-style freedoms and ] and was able to both maintain the dominant role of the Communist Party and to quickly expand and modernise the economy. This, however, has created its own internal tensions and contradictions—as the Chinese working class has massively expanded in numbers, it has begun to do so in ] and class demands, all in odds with the wishes of the State establishment. | |||

| The dominant forms of communism, such as ], ] and ], are based on ], but non-Marxist versions of communism (such as ] and ]) also exist and are growing in importance since the ]. | |||

| ===Anarcho-communism=== | |||

| ], ], ], ], ], ] and ]]] | |||

| {{Main|Anarcho-communism}} | |||

| Some of Marx's contemporaries espoused similar ideas, but differed in their views of how to reach to a classless society. Following the split between those associated with Marx and ] at the ], the anarchists formed the ].<ref>Marshall, Peter. "Demanding the Impossible — A History of Anarchism" p. 9. Fontana Press, London, 1993 ISBN 978-0-00-686245-1</ref> Anarchists argued that capitalism and the state were inseparable and that one could not be abolished without the other. ] such as ] theorized an immediate transition to one society with no classes. ] became one of the dominant forms of ], arguing that ], as opposed to Communist parties, are the organizations that can change society. Consequently, many anarchists have been in opposition to Marxist communism to this day.{{Citation needed|date=April 2008}} | |||

| By the beginning of the 21st century, states controlled by Communist parties under a single-party system include the ], ], ], ], and ]. Communist parties, or their descendant parties, remain politically important in many countries. President ] of ] is a member of the ], both being elected through democratic parliamentary means and these countries are not run under Stalinist single-party rule. In ], the ] is a partner in the ]-led government. In ], Communists lead the governments of three ], with a combined population of more than 115 million. In ], the Communists hold a majority in the ].<ref></ref> | |||

| Anarchist communists propose that the freest form of ] would be a society composed of ] ] with collective use of the ], organized by ], and related to other communes through ].<ref name="LibCom">].. ''The Cienfuegos Press Anarchist Review''. Issue 6 Orkney 1982.</ref> However, some anarchist communists oppose the majoritarian nature of direct democracy, feeling that it can impede individual liberty and favor ].<ref>] and Grubacic, Andrej. ''Anarchism, Or The Revolutionary Movement Of The Twenty-first Century''.</ref> | |||

| The People's Republic of China has reassessed many aspects of the Maoist legacy; and the People's Republic of China, Laos, Vietnam, and, to a far lesser degree, Cuba have reduced centralised state planning of the economy in order to stimulate growth. The People's Republic of China runs ]s dedicated to market-oriented enterprise, free from central government control. As of 2005, anywhere between 33%<ref>http://english.people.com.cn/200507/13/eng20050713_195876.html</ref> (] 2005) to 70%<ref>http://www.businessweek.com/magazine/content/05_34/b3948478.htm</ref> ('']'', 2005) of GDP in 2005, while the OECD estimate is over 50%<ref>http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/16/3/36174313.pdf</ref> of China's GDP came from the private sector, a figure that might be even larger when taking into account the ]. As a result, many observers argue that China has become an entirely free-market economy<ref>Swanson, Tim. . January 20, 2009. Accessed 8 September 2009.</ref> and despite the name of the ] has de facto ceased pursuing the development and establishment of a Communist society. Several other Communist-led states have also attempted to implement ] reforms, including Vietnam, which slowly implemented reforms that transformed the Vietnamese economy into what is officially term a ]. | |||

| ===Christian communism=== | |||

| Today, Marxist-Leninist and Maoist Communists continue to conduct armed insurgencies in ], the ], ], ], ], and ]. | |||

| {{Main|Christian communism}} | |||

| Christian communism is a form of religious communism centered on Christianity. It is a theological and political theory based upon the view that the ] Christ urge Christians to support communism as the ideal ]. Christian communists trace the origins of their practice to teachings in the ], such as this one from ] at chapter 2 and verses 42, 44, and 45: | |||

| ==See also== | |||

| <blockquote>'''42''' ''And they continued steadfastly in the apostles' doctrine and in fellowship '' '''44''' ''And all that believed were together, and had all things in common;'' '''45''' ''And sold their possessions and goods, and parted them to all men, as every man had need.'' (])</blockquote> | |||

| {{colbegin}} | |||

| *] | |||

| Christian communism can be seen as a radical form of ]. Also, due to the fact that many Christian communists have formed independent stateless communes in the past, there is also a link between Christian communism and ]. Christian communists may or may not agree with various parts of ]. | |||

| *] | |||

| *] and ] | |||

| Christian communists also share some of the political goals of Marxists, for example replacing capitalism with ], which should in turn be followed by communism at a later point in the future. However, Christian communists sometimes disagree with Marxists (and particularly with ]) on the way a socialist or communist society should be organized. | |||

| *] and ] | |||

| *] and ] | |||

| ==History== | |||

| *] and ] | |||

| {{Main|History of communism}} | |||

| *] | |||

| ===Early communism=== | |||

| *] | |||

| {{See|Primitive communism|Religious communism}} | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| Karl Heinrich Marx saw ] as the original, ] state of humankind from which it arose. For Marx, only after humanity was capable of producing ], did private property develop.{{Citation needed|date=April 2008}} | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| In the ], certain elements of the idea of a society based on common ownership of property can be traced back to ] .<ref name="encarta"/> Examples include the ] ] in Rome.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.vroma.org/~bmcmanus/spartacus.html |title=Historical Background for Spartacus |publisher=Vroma.org |date= |accessdate=2009-10-18}}</ref> The ] ] movement in what is now ] has been described as "communistic" for challenging the enormous privileges of the noble classes and the clergy, criticizing the institution of private property and for striving for an egalitarian society.<ref>''The Cambridge History of Iran'' Volume 3, , edited by ], Parts 1 and 2, p1019, ] (1983)</ref> | |||

| {{colend}} | |||

| At one time or another, various small communist communities existed, generally under the inspiration of ].<ref name="britannica">"Communism." ''Encyclopædia Britannica''. 2006. ] Online.</ref> In the ] ], for example, some ] communities and ]s shared their land and other property (see ] and ]). These groups often believed that concern with ] was a distraction from religious service to God and neighbor.<ref name="encarta"/> | |||

| Communist thought has also been traced back to the work of ] English writer ]. In his treatise '']'' (1516), More portrayed a society based on ] of property, whose rulers administered it through the application of reason.<ref name="encarta"/> In the 17th century, communist thought arguably surfaced again in England. In 17th century England, a ] ] known as the ] advocated the abolition of private ownership of land.{{Citation needed|date=May 2008}} ], in his 1895 ''Cromwell and Communism''<ref></ref> argued that several groupings in the ], especially the ] espoused clear communistic, agrarian ideals, and that ]'s attitude to these groups was at best ambivalent and often hostile.<ref>Eduard Bernstein, (1895). ''Kommunistische und demokratisch-sozialistische Strömungen während der englischen Revolution'', J.H.W. Dietz, Stuttgart. {{OCLC|36367345}} Sources available at at www.marxists.org.</ref> | |||

| Criticism of the idea of private property continued into the ] of the 18th century, through such thinkers as ] in France.<ref name="encarta"/> Later, following the upheaval of the ], communism emerged as a political doctrine.<ref> "Communism" ''A Dictionary of Sociology''. John Scott and ]. Oxford University Press 2005. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press.</ref> ], in particular, espoused the goals of common ownership of land and total economic and political equality among citizens.<ref name="encarta"/> | |||

| Various social reformers in the early 19th century founded communities based on common ownership. But unlike many previous communist communities, they replaced the religious emphasis with a rational and philanthropic basis.<ref name="britannica"/> Notable among them were ], who founded ] in Indiana (1825), and ], whose followers organized other settlements in the United States such as ] (1841–47).<ref name="britannica"/> Later in the 19th century, Karl Marx described these social reformers as "]" to contrast them with his program of "]" (a term coined by ]). Other writers described by Marx as "utopian socialists" included ]. | |||

| In its modern form, communism grew out of the socialist movement of 19th century Europe.<ref name="encarta"/> As the ] advanced, socialist critics blamed capitalism for the misery of the ] — a new class of urban factory workers who labored under often-hazardous conditions. Foremost among these critics were the ] Karl Marx and his associate Friedrich Engels. In 1848, Marx and Engels offered a new definition of communism and popularized the term in their famous pamphlet '']''.<ref name="britannica"/> Engels, who lived in ], observed the organization of the ] movement (''see ]''), while Marx departed from his university comrades to meet the proletariat in France and Germany.{{Citation needed|date=April 2008}} | |||

| ===Growth of modern communism=== | |||

| ], following his return to ].]] | |||

| {{Main|History of Communism}} | |||

| In the late 19th century, Russian Marxism developed a distinct character. The first major figure of Russian Marxism was ]. Underlying the work of Plekhanov was the assumption that Russia, less urbanized and industrialized than Western Europe, had many years to go before society would be ready for proletarian revolution to occur, and a transitional period of a bourgeois democratic regime would be required to replace ]ism with a socialist and later communist society. (EB){{Citation needed|date=October 2009}} | |||

| In Russia, the ] was the first time any party with an avowedly Marxist orientation, in this case the ], seized ]. The assumption of state power by the Bolsheviks generated a great deal of practical and theoretical debate within the Marxist movement. Marx predicted that socialism and communism would be built upon foundations laid by the most advanced capitalist development. Russia, however, was one of the poorest countries in Europe with an enormous, largely illiterate ] and a minority of industrial workers. Marx had explicitly stated that Russia might be able to skip the stage of bourgeoisie capitalism.<ref>Marc Edelman, "Late Marx and the Russian road: Marx and the 'Peripheries of Capitalism'" - ]s. ''Monthly Review'', Dec., 1984. at www.findarticles.com.</ref> Other socialists also believed that a ] could be the precursor of workers' revolutions in the West. | |||

| The moderate ]s opposed Lenin's Bolshevik plan for ] before capitalism was more fully developed. The Bolsheviks' successful rise to power was based upon the slogans "peace, bread, and land" and "All power to the Soviets", slogans which tapped the massive public desire for an end to Russian involvement in the ], the peasants' demand for ], and popular support for the ].{{Citation needed|date=April 2008}} | |||

| The usage of the terms "communism" and "socialism" shifted after 1917, when the Bolsheviks changed their name to the Communist Party and installed a ] regime devoted to the implementation of socialist policies under ].{{Citation needed|date=April 2008}} The ] had dissolved in 1916 over national divisions, as the separate national parties that composed it did not maintain a unified front against the ], instead generally supporting their respective nation's role. Lenin thus created the ] (Comintern) in 1919 and sent the ], which included ], to all European ] willing to adhere. In France, for example, the majority of the ] (SFIO) party split in 1921 to form the ] (SFIC).{{Citation needed|date=April 2008}} Henceforth, the term "Communism" was applied to the objective of the parties founded under the umbrella of the Comintern. Their program called for the uniting of workers of the world for revolution, which would be followed by the establishment of a ] as well as the development of a ]. Ultimately, if their program held, there would develop a harmonious classless society, with the ].{{Citation needed|date=April 2008}} | |||

| ] | |||

| During the ] (1918–1922), the Bolsheviks ] all productive property and imposed a policy of '']'', which put factories and railroads under strict government control, collected and rationed food, and introduced some bourgeois management of industry. After three years of war and the 1921 ], Lenin declared the ] (NEP) in 1921, which was to give a "limited place for a limited time to capitalism." The NEP lasted until 1928, when ] achieved party leadership, and the introduction of the first Five Year Plan spelled the end of it. Following the Russian Civil War, the Bolsheviks formed in 1922 the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), or ], from the former ]. | |||

| Following Lenin's democratic centralism, the Communist parties were organized on a hierarchical basis, with active cells of members as the broad base; they were made up only of elite ]s approved by higher members of the party as being reliable and completely subject to ].<ref>]. "Communism" ''The Oxford Companion to World War II''. Ed. I. C. B. Dear and ]. Oxford University Press, 2001.</ref> | |||

| After ], Communists consolidated power in ], and in 1949, the ] (CPC) led by ] established the ], which would later follow its own ideological path of Communist development.{{Citation needed|date=April 2008}} ], ], ], ], ], ], and ] were among the other countries in the ] that adopted or imposed a pro-Communist government at some point. Although never formally unified as a single political entity, by the early 1980s almost one-third of the world's population lived in ]s, including the former ] and ]. By comparison, the ] had ruled up to one-quarter of the world's population at its greatest extent.<ref>{{cite news |last=Hildreth |first=Jeremy |title=The British Empire's Lessons for Our own |url=http://online.wsj.com/article/SB111870387824258558.html |work=] |date=2005-06-14 |accessdate=2009-10-18}}</ref> | |||

| Communist states such as Soviet Union and China succeeded in becoming industrial and technological powers, challenging the capitalists' powers in the ] and ] and military conflicts. | |||

| ===Cold War years=== | |||

| ] launching the first artificial satellite ].]] | |||

| By virtue of the Soviet Union's victory in the ] in 1945, the ] had occupied nations in both ] and ]; as a result, communism as a movement spread to many new countries. This expansion of communism both in Europe and Asia gave rise to a few different branches of its own, such as ].{{Citation needed|date=April 2008}} | |||

| Communism had been vastly strengthened by the winning of many new nations into the sphere of Soviet influence and strength in Eastern Europe. Governments modeled on Soviet Communism took power with Soviet assistance in ], ], ], ], ] and ]. A Communist government was also created under ] in ], but Tito's independent policies led to the expulsion of ] from the ], which had replaced the ]. ], a new branch in the world communist movement, was labeled '']''. ] also became an independent Communist nation after World War II.{{Citation needed|date=April 2008}} | |||

| By 1950, the ] held all of ], thus controlling the most populous nation in the world. Other areas where rising Communist strength provoked dissension and in some cases led to actual fighting through conventional and ] include the ], ], many nations of the ] and ], and notably succeeded in the case of the ] against the ] of the United States and its allies. With varying degrees of success, Communists attempted to unite with ] and ] forces against what they saw as ] ] in these poor countries. | |||

| ===Fear of communism=== | |||

| ] book published by the Catechetical Guild Educational Society "warning of the dangers" of a Communist takeover.]] | |||

| {{Main|Red Scare}} | |||

| With the exception of the Soviet Union's, China's and the ]'s great contribution in ], communism was seen as a rival, and a threat to western democracies and capitalism for most of the twentieth century.<ref name="encarta"/> This rivalry peaked during the ], as the world's two remaining superpowers, the United States and the Soviet Union, polarized the world into two camps of nations (characterized in the West as "The Free World" vs. "Behind the Iron Curtain"); supported the spread of their economic and political systems (capitalism and democracy vs. communism); strengthened their military power, developed new weapon systems and stockpiled ]s; competed with each other in space exploration; and even fought each other through proxy client nations. | |||

| Near the beginning of the Cold War, on February 9, 1950, Senator ] from ] accused 205 Americans working in the ] of being "card-carrying Communists".<ref>{{cite book |title=Without Precedent |last=Adams |first=John G. |year=1983 |publisher=W. W. Norton & Company |location=New York, N.Y. |isbn=0-393-01616-1 | |||

| |page=285}}</ref> The fear of communism in the U.S. spurred aggressive investigations and the ], ]ing, jailing and deportation of people suspected of following Communist or other left-wing ideology. Many famous actors and writers were put on a "blacklist" from 1950 to 1954, which meant they would not be hired and would be subject to public disdain.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |title=The Hollywood Blacklist |last=Georgakas |first=Dan |encyclopedia=Encyclopedia of the American Left |publisher=University of Illinois Press |year=1992}}</ref> | |||

| ===After the collapse of the Soviet Union=== | |||

| ], ], ], ] and ].]] | |||

| In 1985, ] became leader of the Soviet Union and relaxed central control, in accordance with reform policies of ] (openness) and ] (restructuring). The Soviet Union did not intervene as ], ], ], ], ], and ] all abandoned Communist rule by 1990. In 1991, the Soviet Union itself dissolved. | |||

| By the beginning of the 21st century, states controlled by Communist parties under a single-party system include the ], ], ], ], and informally ]. Communist parties, or their descendant parties, remain politically important in many countries. President ] of ] is a member of the ], but the country is not run under single-party rule. In ], the ] is a partner in the ]-led government. In ], communists lead the governments of three ], with a combined population of more than 115 million. In ], communists hold a majority in the ].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.economist.com/displaystory.cfm?story_id=11057207&fsrc=nwl |title=Nepal's election The Maoists triumph Economist.com |publisher=Economist.com |date=2008-04-17 |accessdate=2009-10-18}}</ref> | |||

| The People's Republic of China has reassessed many aspects of the Maoist legacy; and the People's Republic of China, Laos, Vietnam, and, to a far lesser degree, Cuba have reduced state control of the economy in order to stimulate growth. The People's Republic of China runs ]s dedicated to market-oriented enterprise, free from ] control. Several other communist states have also attempted to implement market-based reforms, including Vietnam. | |||

| ] in a communist rally in ], ], of a young farmer and worker.]] | |||