| Revision as of 15:45, 10 February 2010 editXashaiar (talk | contribs)Pending changes reviewers4,235 edits Undid revision 343161815 by Nnnnn333k (talk) you already added that same sentence to the article Cyrus_(Bible). dont repeat (link them)← Previous edit | Revision as of 02:57, 11 February 2010 edit undo70.17.103.88 (talk) →ReligionNext edit → | ||

| Line 142: | Line 142: | ||

| ===Religion=== | ===Religion=== | ||

| {{Main|Cyrus in |

{{Main|Cyrus in Jewish tradition|Cyrus the Great in the Qur'an}} | ||

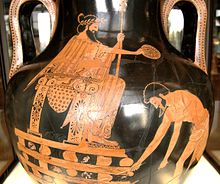

| ] is thought to refer to Cyrus by some Qur'anic commentators.]] | ] is thought to refer to Cyrus by some Qur'anic commentators.]] | ||

| Religious policy of Cyrus is well documented in Babylonian texts as well as Jewish sources. Cyrus initiated a general policy that can be described as a policy of permitting religious freedom throughout his vast empire. He brought peace to the Babylonians and is said to have kept his army away from the temples and restored the statues of the Babylonian gods to their sanctuaries.<ref name=cyrus-EI-iii-religious/> Another example of his religious policies, as evidenced by the Cyrus cylinder (see below), was his treatment of the ]s during their exile in Babylon after ] destroyed ]. The ] ] ends in ] with the decree of Cyrus, which returned the exiles to the ] from Babylon along with a commission to rebuild the temple. | Religious policy of Cyrus is well documented in Babylonian texts as well as Jewish sources. Cyrus initiated a general policy that can be described as a policy of permitting religious freedom throughout his vast empire. He brought peace to the Babylonians and is said to have kept his army away from the temples and restored the statues of the Babylonian gods to their sanctuaries.<ref name=cyrus-EI-iii-religious/> Another example of his religious policies, as evidenced by the Cyrus cylinder (see below), was his treatment of the ]s during their exile in Babylon after ] destroyed ]. The ] ] ends in ] with the decree of Cyrus, which returned the exiles to the ] from Babylon along with a commission to rebuild the temple. | ||

Revision as of 02:57, 11 February 2010

King of Persia, King of Anshan, King of Media, King of Babylon, King of Sumer and Akkad, King of the four corners of the World| Cyrus the Great | |

|---|---|

| King of Persia, King of Anshan, King of Media, King of Babylon, King of Sumer and Akkad, King of the four corners of the World | |

| File:King Cyrus the Great.jpg | |

| Reign | 559 BC-530 BC (30 years) |

| Coronation | Anshan, Persis |

| Predecessor | Cambyses I |

| Successor | Cambyses II |

| Burial | Pasargadae |

| Issue | Cambyses II Bardiya Artystone Atossa Unnamed unknown |

| House | Achaemenid |

| Father | Cambyses I |

| Mother | Mandane of Media or Argoste of Persia |

| Religion | Zoroastrianism |

| Campaigns of Cyrus the Great | |

|---|---|

| Battles against the Satraps

Invasion of Anatolia Invasion of Babylonia |

Cyrus the Great (Old Persian: 𐎤𐎢𐎽𐎢𐏁, IPA: [kʰuːrʰuʃ], Kūruš, Persian: کوروش بزرگ/کوروش کبیر, Kūrošé Bozorg) (c. 600 BC or 576 BC – December 530 BC), also known as Cyrus II or Cyrus of Persia, was the first Zoroastrian Persian emperor. He was the founder of the Persian Empire under the Achaemenid dynasty.

It was under his own rule that the empire embraced all previous civilized states of the ancient Near East, expanded vastly and eventually conquered most of Southwest Asia and much of Central Asia, from Egypt and the Hellespont in the west to the Indus River in the east, to create the largest empire the world had yet seen.

The reign of Cyrus lasted 29 to 31 years. Cyrus built his empire by fighting and conquering first the Median Empire, then the Lydian Empire and the Neo-Babylonian Empire. Either before or after Babylon, he led an expedition into central Asia, which resulted in major campaigns that brought "into subjection every nation without exception." Cyrus did not venture into Egypt, as he himself died in battle, fighting the Massagetae along the Syr Darya in December 530 BC. He was succeeded by his son, Cambyses II, who managed to add to the empire by conquering Egypt, Nubia, and Cyrenaica during his short rule.

As a military leader, Cyrus left a legacy on the art of leadership and decision making, and he attributed his success to "Diversity in counsel, unity in command." Cyrus the Great respected the customs and religions of the lands he conquered. It is said that in universal history, the role of the Achaemenid empire founded by Cyrus lies in its very successful model for centralized administration and establishing a government working to the advantage and profit of its subjects. In fact, the administration of the empire through satraps and the vital principle of forming a government at Pasargadae were the work of Cyrus. Aside from his own nation, Iran, Cyrus also left a lasting legacy on Jewish religion (through his Edict of Restoration), human rights, politics, and military strategy, as well as on both Eastern and Western civilizations.

Background

Etymology

Main article: Etymology of CyrusThe word Cyrus is derived, via Latin, from Ancient Greek, from Old Persian likely originally from Elamite Kurash meaning to bestow care.

The name has been recorded in ancient inscriptions in many different languages. The ancient Greek historians Ctesias and Plutarch noted that Cyrus was named from Kuros, the Sun, a concept which has been interpreted as meaning "like the Sun" by noting its relation to the Persian noun for sun, khor, while using -vash as a suffix of likeness. However, Karl Hoffmann and Rüdiger Schmitt of the Encyclopædia Iranica have suggested the translation "humiliator of the enemy in verbal contest."

In Iran, Cyrus is always referred to as "Kūrošé Bozorg" and/or "Kūrošé Kabīr" —meaning "Cyrus the Great". In the Bible, he is known as simply Koresh (Template:Lang-he).

Dynastic history

See also: Achaemenes and Teispids

The Persian domination and kingdom in the Iranian plateau started by an extension of the Achaemenid dynasty, who expanded their earlier domination possibly from the 9th century BC onward. The eponymous founder of this dynasty was Achaemenes (from Old Persian Haxāmaniš). Achaemenids are "descendants of Achaemenes" as Darius the Great, the ninth king of the dynasty, traces his genealogy to him and declares "for this reason we are called Achaemenids". Achaemenes built the state Parsumash in the southwest of Iran and was succeeded by Teispes, who took the title "King of Anshan" after seizing Anshan city and enlarging his kingdom further to include Pars proper. Ancient documents mention that Teispes had a son called Cyrus I, who also succeeded his father as "king of Anshan". Cyrus I had a full brother whose name is recorded as Ariaramnes.

In 600 BC, Cyrus I was succeeded by his son Cambyses I who reigned until 559 BC. Cyrus the Great was a son of Cambyses I, who named his son after his father, Cyrus I. There are several inscriptions of Cyrus the Great and later kings that refer to Cambyses I as "great king" and "king of Anshan". Among these are some passages in the Cyrus cylinder where Cyrus calls himself "son of Cambyses, great king, king of Anshan". Another inscription (from CM's) mentions Cambyses I as "mighty king" and "an Achaemenian", which according to bulk of scholarly opinion was engraved under Darius and considered as a later forgery by Darius . However "Cambyses II"'s maternal grandfather Pharnaspes is named by Herodotus as "an Achaemenian" too. Xenophon's account in Cyropædia further names Cambyses's wife as Mandane and mentions Cambyses as king of Persia. These agree with Cyrus's own inscriptions, as Anshan and Parsa were different names of the same land. These also agree with other non-Iranian accounts, except at one point from Herodotus that Cambyses was not a king but a "Persian of good family". However, in some other passages, his account is wrong also on the name of the son of Chishpish, which he mentions as Cambyses but, according to modern scholars, should be Cyrus I.

The traditional view which based on archaeological research and the genealogy given in the Behistun Inscription and Herodotus held that Cyrus was an Achaemenian. However it has been suggested by M. Waters and that Cyrus is unrelated to Achaemenes or Darius the Great and that his family was of Teispid and Anshanite origin instead of Achaemenid, though this view is not universally accepted.

Early life

The best-known date for the birth of Cyrus is either 600-599 BC or 576-575 BC. Little is known of his early years, as there are only a few sources known to detail that part of his life, and they have been damaged or lost.

Herodotus' story of Cyrus's early life belongs to a genre of legends in which abandoned children of noble birth, such as Oedipus and Romulus and Remus, return to claim their royal positions. Similar to other culture heroes and founders of great empires, folk traditions abound regarding his family background. According to Herodotus, he was the grandson of the Median king Astyages and was brought up by humble herding folk. In another version, he was presented as the son of poor parents who worked in the Median court. These folk stories are, however, contradicted by his own testimony, according to which he was preceded as king of Persia by his father, grandfather and great-grandfather.

After the birth of Cyrus, Astyages had a dream that his Magi interpreted as a sign that his grandson would eventually overthrow him. He then ordered his steward Harpagus to kill the infant. Harpagus, morally unable to kill a newborn, summoned the Mardian Mitradates (which the historian Nicolaus of Damascus calls Atradates), a royal bandit herdsman from the mountainous region bordering the Saspires, and ordered him to leave the baby to die in the mountains. Luckily, the herdsman and his wife (whom Herodotus calls Cyno in Greek, and Spaca-o in Median) took pity and raised the child as their own, passing off their recently stillbirth infant as the murdered Cyrus. For the origin of Cyrus's mother, Herodotus says Mandane of Media and Ctesias insist that she is full Persian but give no name, while Nicolaus gives the name Argoste as Atradates' wife, whether this figure represents Cyno or Cambyses' unnamed Persian queen has yet to be determined. It is also known that Strabo says that Cyrus was originally named Agradates by his stepparents; therefore, it is probable that, when reuniting with his original family, in custom Cambyses names him (or had named him before the separation) Cyrus after his own father, who was Cyrus I.

Herodotus claims that when Cyrus was ten years old, it was obvious that Cyrus was not a herdsman's son, stating that his behavior was too noble. Astyages interviewed the boy and noticed that they resembled each other. Astyages ordered Harpagus to explain what he had done with the baby, and, after confessing that he had not killed the boy, the king tricked him into eating his own broiled and chopped up son. Astyages was more lenient with Cyrus and allowed him to return to his biological parents, Cambyses and Mandane. While Herodotus's description may be a legend, it does give insight into the figures surrounding Cyrus the Great's early life.

Cyrus had a wife named Cassandane. She was an Achaemenian and daughter of Pharnaspes. From this marriage, Cyrus had four children: Cambyses II, Bardiya, Atossa, and another daughter whose name is not attested in ancient sources. Also, Cyrus had a fifth child named Artystone, the sister or half-sister of Atossa, who may not have been the daughter of Cassandane. Cyrus had a special dearly love for Cassandane, and, according to the chronicle of Nabonidus, when she died, all the nations of Cyrus's empire observed "a great mourning", and, particularly in Babylonia, there was probably even a public mourning lasting for six days (identified from 21–26 March 538 BC). Her tomb is suggested to be at Cyrus's capital, Pasargadae. There are other accounts suggesting that Cyrus the Great also married a daughter of the Median king Astyages, named Amytis. This name may not be the correct one, however. Cyrus probably had once and after the death of Cassandane a Median woman in his royal family. Cyrus' sons Cambyses II and Smerdis both later became kings of Persia, respectively, and his daughter Atossa married Darius the Great and bore him Xerxes I.

Rise and military campaigns

Median Empire

Though his father died in 551 BC, Cyrus had already succeeded to the throne in 559 BC. However, Cyrus was not yet an independent ruler. Like his predecessors, Cyrus had to recognize Median overlordship. During Astyages's reign, the Median Empire may have ruled over the majority of the Ancient Near East, from the Lydian frontier in the west to the Parthians and Persians in the east.

In Herodotus's version, Harpagus, seeking vengeance, convinced Cyrus to rally the Persian people to revolt against their feudal lords, the Medes. However, it is likely that both Harpagus and Cyrus rebelled due to their dissatisfaction with Astyages's policies. From the start of the revolt in summer 553 BC, with his first battles taking place from early 552 BC, Harpagus, with Cyrus, led his armies against the Medes until the capture of Ecbatana in 549 BC, effectively conquering the Median Empire.

While Cyrus seems to have accepted the crown of Media, by 546 BC, he officially assumed the title "King of Persia" instead. With Astyages out of power, all of his vassals (including many of Cyrus's relatives) were now under his command. His uncle Arsames, who had been the king of the city-state of Parsa under the Medes, therefore would have had to give up his throne. However, this transfer of power within the family seems to have been smooth, and it is likely that Arsames was still the nominal governor of Parsa, under Cyrus's authority—more of a Prince or a Grand Duke than a King. His son, Hystaspes, who was also Cyrus' second cousin, was then made satrap of Parthia and Phrygia. Cyrus thus united the twin Achamenid kingdoms of Parsa and Anshan into Persia proper. Arsames would live to see his grandson become Darius the Great, Shahanshah of Persia, after the deaths of both of Cyrus' sons.

Cyrus's conquest of Media was merely the start of his wars. Astyages had been allied with his brother-in-law Croesus of Lydia (son of Alyattes II), Nabonidus of Babylon, and Amasis II of Egypt, who reportedly intended to join forces against Cyrus.

Lydian Empire and Asia Minor

Further information: Battle of Pteria, Battle of Thymbra, and Siege of Sardis

The exact dates of the Lydian conquest are unknown, but it must have taken place between Cyrus's overthrow of the Mede kingdom (550 BC) and his conquest of Babylon (539 BC). It was common in the past to give 547 BC as the year of the conquest due to some interpretations of the Nabonidus Chronicle, but this position is currently not much held. The Lydians first attacked the Achaemenid Empire's city of Pteria in Cappadocia. Croesus besieged and captured the city enslaving its inhabitants. Meanwhile, the Persians invited the citizens of Ionia who were part of the Lydian kingdom to revolt against their ruler. The offer was rebuffed, and thus Cyrus levied an army and marched against the Lydians, increasing his numbers while passing through nations in his way. The Battle of Pteria was effectively a stalemate, with both sides suffering heavy casualties by nightfall. Croesus retreated to Sardis the following morning.

While in Sardis, Croesus sent out requests for his allies to send aid to Lydia. However, near the end of winter, before the allies could unite, Cyrus pushed the war into Lydian territory and besieged Croesus in his capital, Sardis. Shortly before the final Battle of Thymbra between the two rulers, Harpagus advised Cyrus to place his dromedaries in front of his warriors; the Lydian horses, not used to the dromedaries' smell, would be very afraid. The strategy worked; the Lydian cavalry was routed. Cyrus defeated and captured Croesus. Cyrus occupied the capital at Sardis, conquering the Lydian kingdom in 546 BC. According to Herodotus, Cyrus spared Croesus' life and kept him as an advisor, but this account conflicts with some translations of the contemporary Nabonidus Chronicle, which interpret that the king of Lydia was slain.

Before returning to the capital, a Lydian named Pactyes was entrusted by Cyrus to send Croesus' treasury to Persia. However, soon after Cyrus's departure, Pactyes hired mercenaries and caused an uprising in Sardis, revolting against the Persian satrap of Lydia, Tabalus. With recommendations from Croesus that he should turn the minds of the Lydian people to luxury, Cyrus sent Mazares, one of his commanders, to subdue the insurrection but demanded that Pactyas be returned alive. Upon Mazares's arrival, Pactyas fled to Ionia, where he had hired more mercenaries. Mazares marched his troops into the Greek country and subdued the cities of Magnesia and Priene, where Pactyas was captured and sent back to Persia for punishment.

Mazares continued the conquest of Asia Minor but died of unknown causes during his campaign in Ionia. Cyrus sent Harpagus to complete Mazares's conquest of Asia Minor. Harpagus captured Lycia, Cilicia and Phoenicia, using the technique of building earthworks to breach the walls of besieged cities, a method unknown to the Greeks. He ended his conquest of the area in 542 BC and returned to Persia.

Neo-Babylonian Empire

Further information: Battle of Opis

By the year 540 BC, Cyrus captured Elam (Susiana) and its capital, Susa. The Nabonidus Chronicle records that, prior to the battle(s), Nabonidus had ordered cult statues from outlying Babylonian cities to be brought into the capital, suggesting that the conflict had begun possibly in the winter of 540 BC. Near the beginning of October, Cyrus fought the Battle of Opis in or near the strategic riverside city of Opis on the Tigris, north of Babylon. The Babylonian army was routed, and on October 10, Sippar was seized without a battle, with little to no resistance from the populace. It is probable that Cyrus engaged in negotiations with the Babylonian generals to obtain a compromise on their part and therefore avoid an armed confrontation. Nabonidus was staying in the city at the time and soon fled to the capital, Babylon, which he had not visited in years.

Two days later, on October 7 (Gregorian calendar), Gubaru's troops entered Babylon, again without any resistance from the Babylonian armies, and detained Nabonidus. Herodotus explains that to accomplish this feat, the Persians diverted the Euphrates river into a canal so that the water level dropped "to the height of the middle of a man's thigh", which allowed the invading forces to march directly through the river bed to enter at night. On October 29, Cyrus himself entered the city of Babylon and detained Nabonidus.

Prior to Cyrus's invasion of Babylon, the Neo-Babylonian Empire had conquered many kingdoms. In addition to Babylonia itself, Cyrus probably incorporated its subnational entities into his Empire, including Syria, Judea, and Arabia Petraea, although there is no direct evidence of this fact.

After taking Babylon, Cyrus proclaimed himself "king of Babylon, king of Sumer and Akkad, king of the four corners of the world" in the famous Cyrus cylinder, an inscription deposited in the foundations of the Esagila temple dedicated to the chief Babylonian god, Marduk. The text of the cylinder denounces Nabonidus as impious and portrays the victorious Cyrus as pleasing to Marduk. It goes on to describe how Cyrus had improved the lives of the citizens of Babylonia, repatriated displaced peoples and restored temples and cult sanctuaries. Although some have asserted that the cylinder represents a form of human rights charter, historians generally portray it in the context of a long-standing Mesopotamian tradition of new rulers beginning their reigns with declarations of reforms.

Cyrus's dominions comprised the largest empire the world had ever seen. At the end of Cyrus's rule, the Achaemenid Empire stretched from Asia Minor in the west to the northwestern areas of India in the east.

Death

The details of Cyrus's death can vary by account. The account of Herodotus from his Histories provides the second-longest detail, in which Cyrus met his fate in a fierce battle with the Massagetae, a tribe from the southern deserts of Khwarezm and Kyzyl Kum in the southernmost portion of the steppe regions of modern-day Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, following the advice of Croesus to attack them in their own territory. The Massagetae were related to the Scythians in their dress and mode of living; they fought on horseback and on foot. In order to acquire her realm, Cyrus first sent an offer of marriage to their ruler, Tomyris, a proposal she rejected. He then commenced his attempt to take Massagetae territory by force, beginning by building bridges and towered war boats along his side of the river Jaxartes, or Syr Darya, which separated them. Sending him a warning to cease his encroachment in which she stated she expected he would disregard anyway, Tomyris challenged him to meet her forces in honorable warfare, inviting him to a location in her country a day's march from the river, where their two armies would formally engage each other. He accepted her offer, but, learning that the Massagetae were unfamiliar with wine and its intoxicating effects, he set up and then left camp with plenty of it behind, taking his best soldiers with him and leaving the least capable ones. The general of Tomyris's army, who was also her son Spargapises, and a third of the Massagetian troops killed the group Cyrus had left there and, finding the camp well stocked with food and the wine, unwittingly drank themselves into inebriation, diminishing their capability to defend themselves, when they were then overtaken by a surprise attack. They were successfully defeated, and, although he was taken prisoner, Spargapises committed suicide once he regained sobriety. Upon learning of what had transpired, Tomyris denounced Cyrus's tactics as underhanded and swore vengeance, leading a second wave of troops into battle herself. Cyrus was ultimately killed, and his forces suffered massive casualties in what Herodotus referred to as the fiercest battle of his career and the ancient world. When it was over, Tomyris ordered the body of Cyrus brought to her, then decapitated him and dipped his head in a vessel of blood in a symbolic gesture of revenge for his bloodlust and the death of her son. However, some scholars question this version, mostly because Herodotus admits this event was one of many versions of Cyrus's death that he heard from a supposedly reliable source who told him no one was there to see the aftermath. Nevertheless, others suggest the Persian troops may have later recovered the body after it was crucified, which was also after his beheading, or that Tomyris beheaded and then crucified a man other than Cyrus, or Cyrus's double.

Ctesias, in his Persica, has the longest account, which says Cyrus met his death while putting down resistance from the Derbices infantry, aided by other Scythian archers and cavalry, plus Indians and their elephants. According to him, this event took place northeast of the headwaters of the Syr Darya.

An alternative account from Xenophon's Cyropaedia contradicts the others, claiming that Cyrus died peaceably at his capital.

The final version of Cyrus's death comes from Berossus, who only reports Cyrus met his death while warring against the Dahae archers northwest of the headwaters of the Syr Darya.

Tomb

Cyrus' remains were interred in his capital city of Pasargadae, where today a tomb still exists which many believe to be his. Both Strabo and Arrian give nearly equal descriptions of the tomb, based on the eyewitness report of Aristobulus of Cassandreia, who at the instigation of Alexander the Great visited the tomb two times. Though the city itself is now in ruins, the burial place of Cyrus the Great has remained largely intact; and the tomb has been partially restored to counter its natural deterioration over the years. According to Plutarch, his epitaph said,

O man, whoever you are and wherever you come from, for I know you will come, I am Cyrus who won the Persians their empire. Do not therefore begrudge me this bit of earth that covers my bones.

Cuneiform evidence from Babylon proves that Cyrus died around December 530 BC, and that his son Cambyses II had become king. Cambyses continued his father's policy of expansion, and managed to capture Egypt for the Empire, but soon died after only seven years of rule. He was succeeded either by Cyrus' other son Bardiya or an impostor posing as Bardiya, who became the sole ruler of Persia for seven months, until he was killed by Darius the Great.

Cyrus was praised in the Tanakh (Isaiah 45:1–6) and (Ezra 1:1–11) for the freeing of slaves, humanitarian equality and costly reparations he makes. However he has been criticized for believing the false report of the Cuthites, who wanted to halt the rebuilding of the Temple. They accused the Jews of conspiring to rebel, so "the king of Persia" in turn stopped the construction of the Temple, which would not be completed until 516BC, during the reign of Darius the Great. According to the Bible, it was King Artaxerxes who was convinced to stop the construction of the second temple in Jerusalem

Legacy

In scope and extent his achievements ranked far above that of the Macedonian king,

— Charles Freeman in 'The Greek Achievement'

Alexander who was to demolish the empire in the 320's but fail to provide

any stable alternative.

The achievements of Cyrus the Great throughout antiquity is well reflected in the way he is remembered today. His own nation, the Iranians, regarded him as "The Father" and the Babylonians as "The Liberator". After this liberation of Babylonians, followed Cyrus' liberal help for the return of Jews. For this Cyrus is addressed in the Jewish Tanakh as the "Lord's anointed ". Glorified by Ezra and by Isaiah, Cyrus is the one who "The Lord, the God of heaven" has given him "all the Kingdoms of the earth".

Cyrus was distinguished equally as a statesman and as a soldier. By pursuing a policy of generosity instead of repression, and by favoring local religions, he was able to make his newly conquered subjects into enthusiastic supporters. Due in part to the political infrastructure he created, the Achaemenid empire endured long after his death.

The rise of Persia under Cyrus's rule had a profound impact on the course of world history. Persian philosophy, literature and religion all played dominant roles in world events for the next millennia. Despite the Islamic conquest of Persia in the 7th century CE by the Islamic Caliphate, Persia continued to exercise enormous influence in the Middle East during the Islamic Golden Age, and was particularly instrumental in the growth and expansion of Islam.

Many of the Iranian dynasties following the Achaemenid empire and their kings saw themselves as the heirs to Cyrus the Great and have claimed to continue the line begun by Cyrus. However there are different opinions among scholars whether this is also the case for the Sassanid Dynasty. Mohammad Reza Shah of Pahlavi dynasty celebrated the 2500 anniversary of the Iranian monarchy in 1971, though it ended with the 1979 revolution. Even today many consider Cyrus greater than Alexander the Great in his accomplishment.

According to Professor Richard Frye:

It is a testimony to the capability of the founder of the Achaemenian empire that it continued to expand after his death and lasted for more than two centuries. But Cyrus was not only a great conqueror and administrator; he held a place in the minds of the Persian people similar to that of Romulus and Remus in Rome or Moses for the Israelites. His saga follows in many details the stories of hero and conquerors from elsewhere in the ancient world. The manner in which the baby Cyrus was given to a shepherd to raise is reminiscent of Moses in the bulrushes in Egypt, and the overthrow of his tyrannical grandfather has echoes in other myths and legends. There is no doubt that the Cyrus saga arose early among the Persians and was known to the Greeks. The sentiments of esteem or even awe in which Persians held him were transmitted to the Greeks, and it was no accident that Xenophon chose Cyrus to be the model of a ruler for the lessons he wished to impart to his fellow Greeks. In short, the figure of Cyrus has survived throughout history as more than a great man who founded an empire. He became the epitome of the great qualities expected of a ruler in antiquity, and he assumed heroic features as a conqueror who was tolerant and magnanimous as well as brave and daring. His personality as seen by the Greeks influenced them and Alexander the Great, and, as the tradition was transmitted by the Romans, may be considered to influence our thinking even now. In the year 1971, Iran celebrated the 2,500th anniversary of the founding of the monarchy by Cyrus.

Religion

Main articles: Cyrus in Jewish tradition and Cyrus the Great in the Qur'anReligious policy of Cyrus is well documented in Babylonian texts as well as Jewish sources. Cyrus initiated a general policy that can be described as a policy of permitting religious freedom throughout his vast empire. He brought peace to the Babylonians and is said to have kept his army away from the temples and restored the statues of the Babylonian gods to their sanctuaries. Another example of his religious policies, as evidenced by the Cyrus cylinder (see below), was his treatment of the Jews during their exile in Babylon after Nebuchadnezzar II destroyed Jerusalem. The Jewish Bible's Ketuvim ends in Second Chronicles with the decree of Cyrus, which returned the exiles to the Promised Land from Babylon along with a commission to rebuild the temple.

'Thus saith Cyrus king of Persia: All the kingdoms of the earth hath the LORD, the God of heaven, given me; and He hath charged me to build Him a house in Jerusalem, which is in Judah. Whosoever there is among you of all His people--the LORD his God be with him--let him go up.' (Ezra 1:1-4)

This edict is also fully reproduced in the Book of Ezra.

"In the first year of King Cyrus, Cyrus the king issued a decree: ‘Concerning the house of God at Jerusalem, let the temple, the place where sacrifices are offered, be rebuilt and let its foundations be retained, its height being 60 cubits and its width 60 cubits; with three layers of huge stones and one layer of timbers. And let the cost be paid from the royal treasury. ‘Also let the gold and silver utensils of the house of God, which Nebuchadnezzar took from the temple in Jerusalem and brought to Babylon, be returned and brought to their places in the temple in Jerusalem; and you shall put them in the house of God.’ (Ezra 6:3-5)

As a result of Cyrus' policies, the Jews honored him as a dignified and righteous king. He is the only Gentile to be designated as a messiah, a divinely-appointed king, in the Tanakh (Isaiah 45:1-6). Isaiah 45:13: " I will raise up Cyrus in my righteousness: I will make all his ways straight. He will rebuild my city and set my exiles free, but not for a price or reward, says the LORD Almighty." As the text suggests, Cyrus did ultimately release the nation of Israel from its exile without compensation or tribute. Traditionally, these passages in Isaiah were believed to pre-date the rule of Cyrus by about 100 years, however, most modern scholars date Isaiah 40-55(often referred to as Deutero-Isaiah), toward the end of the Babylonian exile(ca. 536 BC). Whereas Isaiah 1-39 (referred to as Proto-Isaiah) saw the destruction of Israel as imminent, and the restoration in the future, Deutero-Isaiah speaks of the destruction in the past (Isa 42:24-25), and the restoration as imminent (Isa 42:1-9). Notice, for example, the change in temporal perspective from (Isa 39:6-7), where the Babylonian Captivity is cast far in the future, to (Isa 43:14), where the Israelites are spoken of as already in Babylon.

There was Jewish criticism of him after he was lied to by the Cuthites, who wanted to halt the building of the Second Temple. They accused the Jews of conspiring to rebel, so Cyrus in turn stopped the construction, which would not be completed until 515 BC, during the reign of Darius I. According to the Bible it was King Artaxerxes who was convinced to stop the construction of the temple in Jerusalem. (Ezra 4:7-24)

Some contemporary Muslim scholars have suggested that the Qur'anic figure of Dhul-Qarnayn is Cyrus the Great. This theory was proposed by Sunni scholar Abul Kalam Azad and endorsed by Shi'a scholars Allameh Tabatabaei, in his Tafsir al-Mizan and Makarem Shirazi.

Politics and philosophy

During his reign, Cyrus maintained control over a vast region of conquered kingdoms, achieved partly through retaining and expanding Median satrapies. Further organization of newly conquered territories into provinces ruled by vassal kings called satraps, was continued by Cyrus' successor Darius the Great. Cyrus' empire was based on tribute and conscripts from the many parts of his realm.

Cyrus' conquests began a new era in the age of empire building, where a vast superstate, comprising many dozens of countries, races, religions, and languages, were ruled under a single administration headed by a central government. This system lasted for centuries, and was retained both by the invading Seleucid dynasty during their control of Persia, and later Iranian dynasties including the Persian Parthians and Sassanids.

On December 10, 2003, in her acceptance of the Nobel Peace Prize, Shirin Ebadi evoked Cyrus, saying:

I am an Iranian, a descendant of Cyrus the Great. This emperor proclaimed at the pinnacle of power 2,500 years ago that he 'would not reign over the people if they did not wish it.' He promised not to force any person to change his religion and faith and guaranteed freedom for all. The Charter of Cyrus the Great should be studied in the history of human rights.

Cyrus' legacy has been felt even as far away as Iceland and colonial America. Many of the forefathers of the United States of America sought inspiration from Cyrus the Great through works such as Cyropaedia. Thomas Jefferson, for example, had two personal copies of the book, "which was a mandatory read for statesmen alongside Machiavelli's The Prince."

Cyrus cylinder

Main article: Cyrus cylinderOne of the few surviving sources of information that can be dated directly to Cyrus's time is the Cyrus cylinder, a document in the form of a clay cylinder inscribed in Akkadian cuneiform. It had been placed in the foundations of the Esagila (the temple of Marduk in Babylon) as a foundation deposit following the Persian conquest in 539 BC. It was discovered in 1879 and is kept today in the British Museum in London.

The text of the cylinder denounces the deposed Babylonian king Nabonidus as impious and portrays Cyrus as pleasing to the chief god Marduk. It goes on to describe how Cyrus had improved the lives of the citizens of Babylonia, repatriated displaced peoples and restored temples and cult sanctuaries. Although not mentioned in the text, the repatriation of the Jews from their "Babylonian captivity" was part of this policy.

The British Museum describes the cylinder as "an instrument of ancient Mesopotamian propaganda" that "reflects a long tradition in Mesopotamia where, from as early as the third millennium BC, kings began their reigns with declarations of reforms." The cylinder emphasizes Cyrus's continuity with previous Babylonian rulers, asserting his virtue as a traditional Babylonian king while denigrating his predecessor.

In the 1970s the Shah of Iran adopted it as a political symbol, using it in his own propaganda celebrating 2,500 years of the Iranian monarchy and asserting that it was "the first human rights charter in history". This view has been disputed by some as "rather anachronistic" and tendentious, as the modern concept of human rights would have been quite alien to Cyrus's contemporaries and is not mentioned by the cylinder. The cylinder has, nonetheless, become seen as part of Iran's cultural identity.

Family tree

Further information: Achaemenid family tree| Cyrus family tree | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes:

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cyrus the Great Achaemenid dynastyBorn: c. 599 BC or 576 BC Died: 530 BC | ||

| Preceded byCambyses I | King of Persia 559 BC–530 BC |

Succeeded byCambyses II |

| Preceded byAstyages | King of Media 550 BC–530 BC | |

See also

Notes

- Ghasemi, Shapour. "The Cyrus the Great Cylinder". Iran Chamber Society. Retrieved 2009-02-22.

- Boyce, Mary. "Achaemenid Religion". Encycloaedia Iranica. Vol. vol. 2. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|volume=has extra text (help); "The Religion of Cyrus the Great" in A. Kuhrt and H. Sancisi-Weerdenburg, eds., Achaemenid History III. Method and Theory, Leiden, 1988. - Ghias Abadi, R. M. (2004). Achaemenid Inscriptions lrm; (in Persian) (2nd edition ed.). Tehran: Shiraz Navid Publications. p. 19. ISBN 964-358-015-6.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - Kent, Ronald Grubb (1384 AP). Old Persian: Grammar, Text, Glossary (in Persian). translated into Persian by S. Oryan. p. 393. ISBN 964-421-045-X.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - (Dandamaev 1989, p. 71)

- Jona Lendering. "livius.org". livius.org. Retrieved 2009-07-19.

- Xenophon, Anabasis I. IX; see also M.A. Dandamaev "Cyrus II", in Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- ^ Schmitt Achaemenid dynasty (i. The clan and dynasty) Cite error: The named reference "schmitt-EI-i" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Kuhrt, Amélie. "13". The Ancient Near East: C. 3000-330 BC. Routledge. p. 647. ISBN 0-4151-6762-0.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help) - Cambridge Ancient History IV Chapter 3c. p. 170. The quote is from the Greek historian Herodotus

- Beckwith, Christopher. (2009). Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691135892. Page 63.

- ^ Cyrus' date of death can be deduced from the last two references to his own reign (a tablet from Borsippa dated to 12 August and the final from Babylon 12 September 530 BC) and the first reference to the reign of his son Cambyses (a tablet from Babylon dated to 31 August and or 4 September), but a undocumented tablet from the city of Kish dates the last official reign of Cyrus to 4 December 530 BC; see R.A. Parker and W.H. Dubberstein, Babylonian Chronology 626 B.C. - A.D. 75, 1971. Cite error: The named reference "date" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- Template:Cite article

- ^ Dandamayev Cyrus (iii. Cyrus the Great) Cyrus’ religious policies.

- The Cambridge Ancient History Vol. IV p. 42. See also: G. Buchaman Gray and D. Litt, The foundation and extension of the Persian empire, Chapter I in The Cambridge Ancient History Vol. IV, 2nd Edition, Published by The University Press, 1927. p. 15. Excerpt: The administration of the empire through satrap, and much more belonging to the form or spirit of the government, was the work of Cyrus...

- ^ Rüdiger Schmitt (i. The name).

- Iranica in the Achaemenid period (ca. 550-330 B.C.): lexicon of old Iranian proper names and loanwords, attested in non-Iranian texts, Volume 158 of Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta, by Jan Tavernier, Peeters Publishers, 2007, ISBN 9042918330, 9789042918337, 850 pages, see page: 528

- The Persian Empire: A Corpus of Sources of the Achaemenid Period, Volume 1, Amélie Kuhrt, published by Routledge, 2007, 736 pages, ISBN 0415436281, 9780415436281, see page: 48

- ; Plutarch, Artaxerxes 1. 3 ; Photius, Epitome of Ctesias' Persica 52

- ^ Max Mallowan p. 392. and p. 417

- e. g. Cyrus Cylinder Fragment A. ¶ 21.

- Schmitt, R. "Iranian Personal Names i.-Pre-Islamic Names". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Vol. Vol. 4.

Naming the grandson after the grandfather was a common practice among Iranians.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Visual representation of the divine and the numinous in early Achaemenid Iran: old problems, new directions; Mark A. Garrison, Trinity University, San Antonio, Texas; last revision: 3 March 2009, see page: 11

- From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire By Briant, Pierre, Translated by Peter T. Daniels, ISBN 1575061201, 9781575061207, see page 63

- M. Waters, "Cyrus and the Achaemenids", Iran 42, 2004 (Achemenet.com > ressources > sous presse). page. 92."Cassandane's identification as such stems primarily from heredotus, but it is supported, directly and indirectly, by analysis of ancient Near Eastern evidence."

- Dandamev, M. A. (1990). "Cambyses". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Encyclopedia Iranica Foundation. ISBN 071009132X.

- (Dandamaev 1989, p. 9)

- M. Waters, "Cyrus and the Achaemenids", Iran 42, 2004 (Achemenet.com > ressources > sous presse), with previous bibliography.

- Most sources give either 600 BC or 575 BC as Cyrus's birth year; the Torah says Cyrus was 40 years old in 559 BC, which would place his birth in 599 BC (as later Biblical scholars mention), but slightly more sources seem to favor 600 BC, indicating a possible error of one year. Cuneiform evidence suggests another possibility for 576 BC, but, again, more sources seem to favor a standard number at 575 BC for his birth. Therefore, a conclusive answer is not yet fully clear.

- Amélie Kuhrt, The Ancient Near East: C.3000 - 330 BC, Routledge Publishers, 1995, p.661, ISBN 0415167620

- Histories of Herodotus, I.110

- ^ Harpagus: Median general, 'kingmaker' of the Persian king Cyrus the Great.

- Stories of the East From Herodotus, Chapter V: The Birth and Bringing Up of Cyrus, p. 66–72.

- Stories of the East From Herodotus, p. 79–80

- Stories of the East From Herodotus, Chapter VI: Cyrus Overthroweth Astyages and Taketh the Kingdom to Himself, p. 84.

- Dandamaev, M. A. (1992). "Cassandane". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Vol. Vol. 5. Encyclopedia Iranica Foundation. ISBN 0933273673.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Schmitt, R. (1985). "Amytis". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Vol. Vol. 1. Encyclopedia Iranica Foundation. ISBN 0933273541.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - P. Briant, From Cyrus to Alexander, pp. 31-33.

- A. Sh. Sahbazi, "Arsama", in Eancyclopaedia Iranica.

- Rollinger, Robert, "The Median "Empire", the End of Urartu and Cyrus' the Great Campaign in 547 B.C."; Lendering, Jona, "The End of Lydia: 547?".

- ^ Herodotus, The Histories, Book I, 440 BC. Translated by George Rawlinson.

- Croesus: Fifth and last king of the Mermnad dynasty.

- Tavernier, Jan. "Some Thoughts in Neo-Elamite Chronology" (PDF). p. 27.

- Kuhrt, Amélie. "Babylonia from Cyrus to Xerxes", in The Cambridge Ancient History: Vol IV — Persia, Greece and the Western Mediterranean, pp. 112-138. Ed. John Boardman. Cambridge University Press, 1982. ISBN 0521228042

- Nabonidus Chronicle, 14.

- Tolini, Gauthier, Quelques éléments concernant la prise de Babylone par Cyrus, Paris. "Il est probable que des négociations s’engagèrent alors entre Cyrus et les chefs de l’armée babylonienne pour obtenir une reddition sans recourir à l’affrontement armé." p. 10 (PDF)

- The Harran Stelae H2 - A, and the Nabonidus Chronicle (Seventeenth year) show that Nabonidus had been in Babylon before October 10, 539, because he had already returned from Harran and had participated in the Akitu of Nissanu 1 , 539 BC.

- Nabonidus Chronicle, 15-16.

- Missler, Chuck, The Fall of Babylon Versus The Destruction of Babylon, p. 2 (PDF)

- Nabonidus Chronicle, 18.

- M.A. Dandamaev, "Cyrus II", in Encyclopaedia Iranica; P. Briant, From Cyrus to Alexander, pp. 44-49.

- ^ British Museum Website,The Cyrus Cylinder

- M.A. Dandamaev, "Cyrus II", in Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- "Ancient History Sourcebook: Herodotus: Queen Tomyris of the Massagetai and the Defeat of the Persians under Cyrus"

- Tomyris, Queen of the Massagetae, Defeats Cyrus the Great in Battle Herodotus, The Histories

- Ancient History Sourcebook: Herodotus: Queen Tomyris of the Massagetae and the Defeat of the Persians under Cyrus

- Xenophon, Cyropaedia VII. 7; M.A. Dandamaev, "Cyrus II", in Encyclopaedia Iranica, p. 250. See also H. Sancisi-Weerdenburg "Cyropaedia", in Encyclopaedia Iranica, on the reliability of Xenophon's account.

- Strabo, Geographica 15.3.7; Arrian, Anabasis Alexandri 6.29

- Life of Alexander, 69, in Plutarch: The Age of Alexander, translated by Ian Scott-Kilvert (Penguin Classics, 1973), p.326.; similar inscriptions give Arrian and Strabo.

- "Search for a Bible passage in over 35 languages and 50 versions". BibleGateway.com. Retrieved 2009-07-19.

- Freeman 1999: p. 188

- Cardascia, G., Babylon under Achaemenids, in Encyclopedia Iranica.

- Schaff, Philip, The New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge, Vol. III, Cyrus the Great

- E. Yarshater, for example, rejects that Sassanids remembered Cyrus, whereas R. N. Frye do propose remembrance and line of continuity: See A. Sh. Shahbazi, Early Sassanians' Claim to Achaemenid Heritage, Namey-e Iran-e Bastan, Vol. 1, No. 1 pp. 61-73; M. Boyce, "The Religion of Cyrus the Great" in A. Kuhrt and H. Sancisi-Weerdenburg, eds., Achaemenid History III. Method and Theory, Leiden, 1988, p. 30; and The History of Ancient Iran, by Frye p. 371; and the debates in Vesta Sarkhosh Curtis, et al. The Art and Archaeology of Ancient Persia: New Light on the Parthian and Sasanian Empires, Published by I.B. Tauris in association with the British Institute of Persian Studies, 1998, ISBN 1860640451, pp. 1-8 and pp. 38-51.

- "Cyrus II." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2008. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 28 July 2008 <http://original.britannica.com/eb/article-1685>.

- http://books.google.ca/books?id=sC046IfH-I8C&pg=PA126

- http://books.google.ca/books?id=goq0VWw9rGIC&pg=PA414

- Goldwurm, Hersh (1982). History of the Jewish People: The Second Temple Era. ArtScroll. pp. 26, 29. ISBN 0-8990-6454-X.

- Schiffman, Lawrence (1991). From text to tradition: a history of Second Temple and Rabbinic Judaism. KTAV Publishing. pp. 35, 36. ISBN 0881253723, 9780881253726.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - Wilcox, Peter (1986). Rome's Enemies: Parthians And Sassanid Persians. Osprey Publishing. p. 14. ISBN 0850456886.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Nobel acceptance speech by Shirin Ebadi, "All Human Beings Are To Uphold Justice" (translated); accessed 24 August 2006. (The quote is not authentic.)

- Jakob Jonson: "Cyrus the Great in Icelandic epic: A literary study". Acta Iranica. 1974: 49-50

- Interview with Cliff Rogers, United States Military Academy Link:

- H.F. Vos, "Archaeology of Mesopotamia", p. 267 in The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, ed. Geoffrey W. Bromiley. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 1995. ISBN 0802837816

- "The Ancient Near East, Volume I: An Anthology of Texts and Pictures". Vol. 1. Ed. James B. Pritchard. Princeton University Press, 1973.

- "British Museum - Cyrus Cylinder". British Museum. Retrieved 28 October 2009.

- Hekster, Olivier; Fowler, Richard (2005). Imaginary kings: royal images in the ancient Near East, Greece and Rome. Vol. Oriens et occidens 11. Franz Steiner Verlag. p. 33. ISBN 9783515087650.

- ^ British Museum explanatory notes, "Cyrus Cylinder": "For almost 100 years the cylinder was regarded as ancient Mesopotamian propaganda. This changed in 1971 when the Shah of Iran used it as a central image in his own propaganda celebrating 2500 years of Iranian monarchy. In Iran, the cylinder has appeared on coins, banknotes and stamps. Despite being a Babylonian document it has become part of Iran's cultural identity."

- Neil MacGregor, "The whole world in our hands", in Art and Cultural Heritage: Law, Policy, and Practice, p. 383-4, ed. Barbara T. Hoffman. Cambridge University Press, 2006. ISBN 0521857643

- Elton L. Daniel, The History of Iran, p. 39. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2000. ISBN 0313307318

- John Curtis, Nigel Tallis, Beatrice Andre-Salvini. Forgotten Empire, p. 59. University of California Press, 2005.

- See also Amélie Kuhrt, "Babylonia from Cyrus to Xerxes", in The Cambridge Ancient History: Vol IV - Persia, Greece and the Western Mediterranean, p. 124. Ed. John Boardman. Cambridge University Press, 1982. ISBN 0521228042

- "Family Tree of Darius the Great" (JPG). Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 2011-03-28.

References

Ancient sources

- The Nabonidus Chronicle of the Babylonian Chronicles

- The Verse account of Nabonidus

- The Prayer of Nabonidus (one of the Dead Sea scrolls)

- The Cyrus Cylinder

- Herodotus (The Histories)

- Ctesias (Persica)

- The biblical books of Isaiah, Daniel, Ezra and Nehemiah

- Flavius Josephus (Antiquities of the Jews)

- Thucydides (History of the Peloponnesian War)

- Plato (Laws (dialogue))

- Xenophon (Cyropaedia)

- Quintus Curtius Rufus (Library of World History)

- Fragments of Nicolaus of Damascus

- Arrian (Anabasis Alexandri)

- Polyaenus (Stratagems in War)

- Justin (Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus) Template:En icon

- Polybius (The Histories (Polybius))

- Diodorus Siculus (Bibliotheca historica)

- Athenaeus (Deipnosophistae)

- Strabo (History)

Modern sources

- Herodotus; Church, Alfred J., Stories of the East From Herodotus (1891). ISBN 0-7661-8928-7

- Schmitt, Rüdiger. "Achaemenid dynasty". Encycloaedia Iranica. Vol. vol. 3. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Cardascia, G. "Babylon under Achaemenids". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Vol. Vol. 3. ISBN 0939214784.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|volume=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=,|accessmonth=, and|accessyear=(help) - Schmitt, Rüdiger; Shahbazi, A. Shapur; Dandamayev, Muhammad A.; Zournatzi, Antigoni. "Cyrus". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Vol. Vol. 6. ISBN 0939214784.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|volume=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameters:|accessyear=,|month=,|accessmonth=, and|coauthors=(help) - Freeman, Charles (1999). The Greek Achievement: The Foundation of the Western World. Allen Lane. ISBN 0713992247.

- The Cambridge History of Iran: Vol. 2 ; The Median and Achaemenian periods. Cambridge University Press. 1985. ISBN 0521200911.

- The Cambridge Ancient History IV: Persia, Greece, and the Western Mediterranean, C. 525-479 B.C. ISBN 0521228042.

- Dandamaev, M. A. (1989). A political history of the Achaemenid empire. BRILL. p. 373. ISBN 9004091726.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Frye, Richard N., The Heritage of Persia. Weidenfeld and Nicolson (1962), 40, 43-4, 46-7, 70, 75, 78-90, 93, 104, 108, 122, 127, 206-7. ISBN 1-56859-008-3

- Moorey, P.R.S., The Biblical Lands, VI. Peter Bedrick Books, New York (1991). ISBN 0-87226-247-2

- Olmstead, A. T., History of the Persian Empire . University of Chicago Press (1948). ISBN 0-226-62777-2

- Palou, Christine; Palou, Jean, La Perse Antique. Presses Universitaires de France (1962).

- Nos ancêtres de l'Antiquité, 1991, Christian Settipani, p. 146, 152 and 157

External links

- The Day of Cyrus The Great The Day of Cyrus The Great in Cambridge/UK

- Historic Personalities - Cyrus the Great Iran Chamber Society

- Cyropaedia of Xenophon Iran Chamber Society

- PersianDNA Cyrus The Great - Persian Empire & The Greatest King of the History

- Pictures of Tomb of Cyrus the Great

- Cyrus Cylinder Full Babylonian text of the Cyrus Cylinder as it was known in 2001; translation; brief introduction

- Cylinder of Cyrus, Persian text منشور کوروش هخامنشی

- Who Was Zulqarnain?

- Cyrus The Great

- International Committee to Save the Archaeological Sites of Pasargadae.

- Images of Cyrus the Great's tomb

- Cyrus Cylinder to be returned to Iran Cultural Heritage News Agency, Tehran, June 2008

- Iran, The Forgotten Glory - Documentary Film About Ancient Persia (Achaemenids & Sassanids)

- A short sample of the documentary film In Search of Cyrus the Great, directed by Cyrus Kar, in production, hosted by International Committee to Save the Archaeological Sites of Pasargadae (9 min 58 sec).

- Xenophon, Cyropaedia: the education of Cyrus, translated by Henry Graham Dakyns and revised by F.M. Stawell, Project Gutenberg.