| Revision as of 00:55, 13 March 2010 edit98.113.222.173 (talk)No edit summary← Previous edit | Revision as of 00:55, 13 March 2010 edit undoMaterialscientist (talk | contribs)Edit filter managers, Autopatrolled, Checkusers, Administrators1,994,294 editsm Reverted edits by 98.113.222.173 (talk) to last version by MaterialscientistNext edit → | ||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

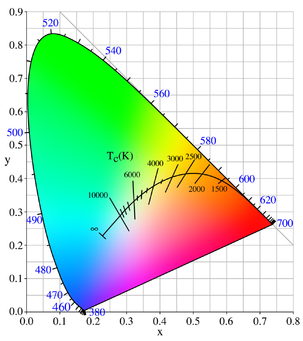

| ]) of black-body radiation depends on the temperature of the black body; the ] of such colors, shown here in ], is known as the ].]] | ]) of black-body radiation depends on the temperature of the black body; the ] of such colors, shown here in ], is known as the ].]] | ||

| ], a '''black body''' is an idealized ] that absorbs all ] that falls on it. No electromagnetic radiation passes through it and none is ]. Because no light (visible electromagnetic radiation) is reflected or transmitted, the object appears black when it is cold. However, a black body emits a temperature-dependent ] of light. This ] from a black body is termed '''black-body radiation'''.<ref group="nb">When used as a ], the term is typically hyphenated, as in "black-body radiation", or combined into one word, as in "blackbody radiation". The hyphenated and one-word forms should not generally be used as nouns.</ref> | In ], a '''black body''' is an idealized ] that absorbs all ] that falls on it. No electromagnetic radiation passes through it and none is ]. Because no light (visible electromagnetic radiation) is reflected or transmitted, the object appears black when it is cold. However, a black body emits a temperature-dependent ] of light. This ] from a black body is termed '''black-body radiation'''.<ref group="nb">When used as a ], the term is typically hyphenated, as in "black-body radiation", or combined into one word, as in "blackbody radiation". The hyphenated and one-word forms should not generally be used as nouns.</ref> | ||

| At room temperature, black bodies emit mostly ] wavelengths, but as the temperature increases past a few hundred degrees ], black bodies start to emit visible wavelengths, appearing red, orange, yellow, white, and blue with increasing temperature. By the time an object is white, it is emitting substantial ] radiation. | At room temperature, black bodies emit mostly ] wavelengths, but as the temperature increases past a few hundred degrees ], black bodies start to emit visible wavelengths, appearing red, orange, yellow, white, and blue with increasing temperature. By the time an object is white, it is emitting substantial ] radiation. | ||

Revision as of 00:55, 13 March 2010

In physics, a black body is an idealized object that absorbs all electromagnetic radiation that falls on it. No electromagnetic radiation passes through it and none is reflected. Because no light (visible electromagnetic radiation) is reflected or transmitted, the object appears black when it is cold. However, a black body emits a temperature-dependent spectrum of light. This thermal radiation from a black body is termed black-body radiation.

At room temperature, black bodies emit mostly infrared wavelengths, but as the temperature increases past a few hundred degrees Celsius, black bodies start to emit visible wavelengths, appearing red, orange, yellow, white, and blue with increasing temperature. By the time an object is white, it is emitting substantial ultraviolet radiation.

The term "black body" was introduced by Gustav Kirchhoff in 1860.

Black-body emission gives insight into the thermal equilibrium state of a continuous field. In classical physics, each different Fourier mode in thermal equilibrium should have the same energy. This approach led to the paradox known as the ultraviolet catastrophe, that there would be an infinite amount of energy in any continuous field. Black bodies could test the properties of thermal equilibrium because they emit radiation which is distributed thermally. Studying the laws of the black body historically led to quantum mechanics.

Explanation

Black-body radiation is light in thermal equilibrium with a black body, light radiation with a given temperature. It is the reference thermodynamic equilibrium state of light. Experimentally, it is established as the steady state equilibrium radiation in a rigid-walled cavity that contains a black body. There are no strictly exact black bodies in nature, but graphite is a good approximation, and a closed box with graphite walls at a steady state gives a good approximation to ideal black body radiation. A cavity that does not contain any black material body does not sustain black body radiation at equilibrium; this fact was found experimentally by Kirchhoff but its physical significance was understood neither by Kirchhoff nor by Planck.

Because light is the oscillation of a continuous electromagnetic field, the study of black-body radiation reveals how continuous fields can have a temperature, something which contradicts classical physics. Because the thermal state of light was so confusing before the advent of quantum mechanics, the 19th century arguments that light has a thermal equilibrium state were made very carefully.

An object at some fixed temperature T, like an oven, is observed to glow. The Draper point is the name given to the point at which all solids glow a dim red (about 798 K). At 1000 K, an oven looks red; at 6000 K, it looks white. No matter how the oven is constructed, so long as the oven is not too shiny, the color of the light only depends on the temperature. Since color is the directly visible measure of the wavelength, this observation means that light at different temperatures has a different distribution of energy among the different wavelengths. The amount of energy E per unit volume in wavelength λ at temperature T is called the black-body curve. Detailed experiments revealed that the black-body curve only depends on the temperature, not on the emitting body. This suggests that light does in fact come to thermal equilibrium just like anything else, that the concept of light at temperature T makes sense.

Two things that are at the same temperature stay in equilibrium, so a body at temperature T surrounded by a cloud of light at temperature T on average will emit as much light into the cloud as it absorbs, following Prevost's exchange principle, which refers to radiative equilibrium. The principle of detailed balance says that there are no strange correlations between the process of emission and absorption: the process of emission is not affected by the absorption, but only by the thermal state of the emitting body. This means that the total light emitted by a body at temperature T, black or not, is always equal to the total light that the body would absorb were it to be surrounded by light at temperature T.

When the body is black, the absorption is obvious: the amount of light absorbed is all the light that hits the surface. For a black body much bigger than the wavelength, the light energy absorbed at any wavelength λ per unit time is strictly proportional to the black-body curve. This means that the black-body curve is the amount of light energy emitted by a black body, which justifies the name. This is Kirchhoff's law of thermal radiation: the black-body emission curve is a thermal characteristic of light, which depends only on the temperature of the walls of the cavity, provided strictly that the cavity contains some perfectly black material body and is in radiative equilibrium.

In the laboratory, black-body radiation is approximated by the radiation from a small hole entrance to a large cavity, a hohlraum, that contains a black body, and that has reached and is maintained at equilibrium. (This technique leads to the alternative term cavity radiation.) Any light entering the hole would have to reflect off the walls of the cavity multiple times before it escaped, in which process it is nearly certain to be absorbed. This occurs regardless of the wavelength of the radiation entering (as long as it is small compared to the hole). The hole, then, is a close approximation of a theoretical black body and, if the cavity is heated, the spectrum of the hole's radiation (i.e., the amount of light emitted from the hole at each wavelength) will be continuous, strictly provided that the cavity must contain some nearly perfectly black material body and that equilibrium has been reached and is maintained, but with these provisoes, it does not further depend on the other material in the cavity (compare with emission spectrum).

Calculating the black-body curve was a major challenge in theoretical physics during the late nineteenth century. The problem was finally solved in 1901 by Max Planck as Planck's law of black-body radiation. By making changes to Wien's radiation law (not to be confused with Wien's displacement law) consistent with thermodynamics and electromagnetism, he found a mathematical formula fitting the experimental data in a satisfactory way. To find a physical interpretation for this formula, Planck had then to assume that the energy of the oscillators in the cavity was quantized (i.e., integer multiples of some quantity). Einstein built on this idea and proposed the quantization of electromagnetic radiation itself in 1905 to explain the photoelectric effect. These theoretical advances eventually resulted in the superseding of classical electromagnetism by quantum electrodynamics. Today, these quanta are called photons and the black-body cavity may be thought of as containing a gas of photons. In addition, it led to the development of quantum probability distributions, called Fermi-Dirac statistics and Bose-Einstein statistics, each applicable to a different class of particle, which are used in quantum mechanics instead of the classical distributions. See also fermion and boson.

The wavelength at which the radiation is strongest is given by Wien's displacement law, and the overall power emitted per unit area is given by the Stefan-Boltzmann law. So, as temperature increases, the glow color changes from red to yellow to white to blue. Even as the peak wavelength moves into the ultra-violet, enough radiation continues to be emitted in the blue wavelengths that the body will continue to appear blue. It will never become invisible—indeed, the radiation of visible light increases monotonically with temperature.

The radiance or observed intensity is not a function of direction. Therefore a black body is a perfect Lambertian radiator.

Real objects never behave as full-ideal black bodies, and instead the emitted radiation at a given frequency is a fraction of what the ideal emission would be. The emissivity of a material specifies how well a real body radiates energy as compared with a black body. This emissivity depends on factors such as temperature, emission angle, and wavelength. However, it is typical in engineering to assume that a surface's spectral emissivity and absorptivity do not depend on wavelength, so that the emissivity is a constant. This is known as the grey body assumption.

Due to the rapid fall-off of emitted photons with decreasing energy, a black body at room temperature (300 K) with 1 m of surface area emits a visible photon every thousand years or so, which is negligible for most purposes.

When dealing with non-black surfaces, the deviations from ideal black-body behavior are determined by both the geometrical structure and the chemical composition, and, provided there is a radiative equilibrium with a nearly black body that is present, nearly follow Kirchhoff's Law: emissivity equals absorptivity, so that an object that does not absorb all incident light will also emit less radiation than an ideal black body.

In astronomy, objects such as stars are frequently regarded as black bodies, though this is often a poor approximation. An almost perfect black-body spectrum is exhibited by the cosmic microwave background radiation. Hawking radiation is the hypothetical black-body radiation emitted by black holes.

Black-body simulators

Although a black body is a theoretical object (i.e. emissivity e = 1.0), common applications define a source of infrared radiation as a black body when the object approaches an emissivity of 1.0, (typically e = 0.99 or better). A source of infrared radiation less than 0.99 is referred to as a "grey body". Applications for black body simulators typically include the testing and calibration of infrared systems and infrared sensor equipment.

Super black is an example of such a material, made from a nickel-phosphorus alloy. More recently, a team of Japanese scientists created a material even closer to a black body, based on vertically aligned single-walled carbon nanotubes, which absorbs between 98% and 99% of the incoming light, in the spectral range from UV to far infrared.

Equations governing black bodies

Planck's law of black-body radiation

Main article: Planck's lawPlanck's law states that

where

- I(ν,T) dν is the amount of energy per unit surface area per unit time per unit solid angle emitted in the frequency range between ν and ν + dν by a black body at temperature T;

- h is the Planck constant;

- c is the speed of light in a vacuum;

- k is the Boltzmann constant;

- ν is frequency of electromagnetic radiation; and

- T is the temperature in kelvins.

Wien's displacement law

Main article: Wien's displacement lawWien's displacement law shows how the spectrum of black body radiation at any temperature is related to the spectrum at any other temperature. If we know the shape of the spectrum at one temperature, we can calculate the shape at any other temperature.

A consequence of Wien's displacement law is that the wavelength at which the intensity of the radiation produced by a black body is at a maximum, , it is a function only of the temperature:

where the constant, b, known as Wien's displacement constant, is equal to 2.8977685(51)×10 m K.

Note that the peak intensity can be expressed in terms of intensity per unit wavelength or in terms of intensity per unit frequency. The form given in this section is in terms of intensity per unit wavelength, this form given in the Planck's Law section above was in terms of intensity per unit frequency. The wavelength at which the power per unit frequency is maximised is given by

- .

Stefan–Boltzmann law

Main article: Stefan–Boltzmann lawThis law states that the power emitted per unit area of the surface of a black body is directly proportional to the fourth power of its absolute temperature. That is

where j*is the total power radiated per unit area, T is the temperature (specified in a temperature system where 0 is at absolute zero, such as the kelvin scale,) and σ = 5.67×10 W m K is the Stefan–Boltzmann constant.

Radiation emitted by a human body

|

|

| Much of a person's energy is radiated away in the form of infrared energy. Some materials are transparent to infrared light, while opaque to visible light (note the plastic bag). Other materials are transparent to visible light, while opaque or reflective to the infrared (note the man's glasses). |

Black-body laws can be applied to human beings. For example, some of a person's energy is radiated away in the form of electromagnetic radiation, most of which is infrared.

The net power radiated is the difference between the power emitted and the power absorbed:

Applying the Stefan–Boltzmann law,

- .

The total surface area of an adult is about 2 m², and the mid- and far-infrared emissivity of skin and most clothing is near unity, as it is for most nonmetallic surfaces. Skin temperature is about 33°C, but clothing reduces the surface temperature to about 28 °C when the ambient temperature is 20 °C. Hence, the net radiative heat loss is about

- .

The total energy radiated in one day is about 9 MJ (megajoules), or 2000 kcal (food calories). Basal metabolic rate for a 40-year-old male is about 35 kcal/(m·h), which is equivalent to 1700 kcal per day assuming the same 2 m area. However, the mean metabolic rate of sedentary adults is about 50% to 70% greater than their basal rate.

There are other important thermal loss mechanisms, including convection and evaporation. Conduction is negligible since the Nusselt number is much greater than unity. Evaporation (perspiration) is only required if radiation and convection are insufficient to maintain a steady state temperature. Free convection rates are comparable, albeit somewhat lower, than radiative rates. Thus, radiation accounts for about two-thirds of thermal energy loss in cool, still air. Given the approximate nature of many of the assumptions, this can only be taken as a crude estimate. Ambient air motion, causing forced convection, or evaporation reduces the relative importance of radiation as a thermal loss mechanism.

Also, applying Wien's Law to humans, one finds that the peak wavelength of light emitted by a person is

- .

This is why thermal imaging devices designed for human subjects are most sensitive to 7000–14000 nanometers wavelength.

Temperature relation between a planet and its star

Here is an application of black-body laws to roughly estimate the temperature of a planet. The surface may be warmer due to the greenhouse effect.

Factors

The temperature of a planet depends on a few factors:

- Incident radiation (from the Sun, for example)

- Emitted radiation (for example Earth's infrared glow)

- The albedo effect (the fraction of light a planet reflects)

- The greenhouse effect (for planets with an atmosphere)

- Energy generated internally by a planet itself (due to radioactive decay, tidal heating and adiabatic contraction due to cooling).

For the inner planets, incident and emitted radiation have the most significant impact on temperature. This derivation is concerned mainly with that.

Derivation

The Stefan–Boltzmann law gives the total power (energy/second) the Sun is emitting:

where

- is the Stefan–Boltzmann constant,

- is the surface temperature of the Sun, and

- is the radius of the Sun.

The Sun emits that power equally in all directions. Because of this, the Earth is hit with only a tiny fraction of it. The power from the Sun that strikes the Earth (at the top of the atmosphere) is:

where

- is the radius of the Earth and

- is the astronomical unit, the distance between the Sun and the Earth.

Because of its high temperature, the sun emits to a large extent in the ultraviolet and visible (UV-Vis) frequency range. In this frequency range, the Earth reflects a fraction of this energy where is the albedo or reflectance of the Earth in the UV-Vis range. In other words, the Earth absorbs a fraction of the sun's light, and reflects the rest. The power absorbed by the Earth and its atmosphere is then:

Even though the Earth only absorbs as a circular area , it emits equally in all directions as a sphere. If the Earth were a perfect black body, it would emit according to the Stephan-Boltzmann law

where is the temperature of the Earth. The Earth, since it is at a much lower temperature than the sun, emits mostly in the infrared (IR) portion of the spectrum. In this frequency range, it emits of the radiation that a black body would emit where is the average emissivity in the IR range. The power emitted by the Earth and its atmosphere is then:

Assuming that the Earth is in thermal equilibrium, the power absorbed must equal the power emitted:

Substituting the expressions for solar and Earth power in equations 1-6 and simplifying yields:

In other words, given the assumptions made, the temperature of Earth depends only on the surface temperature of the Sun, the radius of the Sun, the distance between Earth and the Sun, the albedo and the IR emissivity of the Earth.

Temperature of Earth

If we substitute in the measured values for the Sun and Earth:

If we set the average emissivity to unity, we calculate the "effective temperature" of the Earth to be:

- 254.356 K or -18.8 C.

This is the temperature that the Earth would be at if it radiated as a perfect black body in the infrared, ignoring greenhouse effects, and assuming an unchanging albedo. The Earth in fact radiates almost as a perfect black body in the infrared which will raise the estimated temperature a few degrees above the effective temperature. If we wish to estimate what the temperature of the Earth would be if it had no atmosphere, then we could take the albedo and emissivity of the moon as a good estimate. The albedo and emissivity of the moon are about 0.1054 and 0.95 respectively, yielding an estimated temperature of about 1.36 C.

Estimates of the Earth's average albedo vary in the range 0.3–0.4, resulting in different estimated effective temperatures. Estimates are often based on the solar constant (total insolation power density) rather than the temperature, size, and distance of the sun. For example, using 0.4 for albedo, and an insolation of 1400 W m), one obtains an effective temperature of about 245 K. Similarly using albedo 0.3 and solar constant of 1372 W m), one obtains an effective temperature of 255 K.

Doppler effect for a moving black body

The Doppler effect is the well known phenomenon describing how observed frequencies of light are "shifted" when a light source is moving relative to the observer. If f is the emitted frequency of a monochromatic light source, it will appear to have frequency f' if it is moving relative to the observer:

where v is the velocity of the source in the observer's rest frame, θ is the angle between the velocity vector and the observer-source direction, and c is the speed of light. This is the fully relativistic formula, and can be simplified for the special cases of objects moving directly towards (θ = π) or away (θ = 0) from the observer, and for speeds much less than c.

To calculate the spectrum of a moving black body, then, it seems straightforward to simply apply this formula to each frequency of the blackbody spectrum. However, simply scaling each frequency like this is not enough. We also have to account for the finite size of the viewing aperture, because the solid angle receiving the light also undergoes a Lorentz transformation. (We can subsequently allow the aperture to be arbitrarily small, and the source arbitrarily far, but this cannot be ignored at the outset.) When this effect is included, it is found that a black body at temperature T that is receding with velocity v appears to have a spectrum identical to a stationary black body at temperature T', given by:

For the case of a source moving directly towards or away from the observer, this reduces to

Here v > 0 indicates a receding source, and v < 0 indicates an approaching source.

This is an important effect in astronomy, where the velocities of stars and galaxies can reach significant fractions of c. An example is found in the cosmic microwave background radiation, which exhibits a dipole anisotropy from the Earth's motion relative to this blackbody radiation field.

See also

- Bolometer

- Color temperature

- Effective temperature

- Emissivity

- Infrared thermometer

- Photon polarization

- Pyrometry

- Rayleigh-Jeans law

- Super black

- Thermal radiation

- Thermography

- Ultraviolet catastrophe

Notes

- When used as a compound adjective, the term is typically hyphenated, as in "black-body radiation", or combined into one word, as in "blackbody radiation". The hyphenated and one-word forms should not generally be used as nouns.

- There is a subtlety when the black body is small, so that its size is comparable to the wavelength of light. In this case, the absorption is modified, because a small object is not an efficient absorber of light of long wavelength. But the principle of strict equality of emission and absorption is always upheld.

References

- G. Kirchhoff (1896). On the relation between the Radiating and Absorbing Powers of different Bodies for Light and Heat, translated by F. Guthrie in Phil. Mag. Series 4, volume 20, number 130, pages 1-21, original in Poggendorff's Annalen, vol. 109, pages 275 et seq.

- M. Planck (1914). The theory of heat radiation, second edition, translated by M. Masius, Blackiston's Son & Co, Philadelphia.

- Robitaille, P. (2003). "On the validity of Kirchhoff's law of thermal emission". IEEE Transactions on Plasma Science. 31: 1263. doi:10.1109/TPS.2003.820958.

- "Science: Draper's Memoirs". The Academy. XIV (338). London: Robert Scott Walker: 408. Oct. 26, 1878.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - J. R. Mahan (2002). Radiation heat transfer: a statistical approach (3rd ed.). Wiley-IEEE. p. 58. ISBN 9780471212706.

- Huang, Kerson (1967). Statistical Mechanics. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- Planck, Max (1901). "On the Law of Distribution of Energy in the Normal Spectrum" (). Annalen der Physik. 4: 553.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Landau, L. D. (1996). Statistical Physics (3rd Edition Part 1 ed.). Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Electro Optical Industries, Inc. (2008) What is a Black Body and Infrared Radiation? In BB Radiation

- K. Mizuno; et al. (2009). "A black body absorber from vertically aligned single-walled carbon nanotubes". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106: 6044–6077. doi:10.1073/pnas.0900155106.

{{cite journal}}:|format=requires|url=(help); Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - Infrared Services. "Emissivity Values for Common Materials". Retrieved 2007-06-24.

- Omega Engineering. "Emissivity of Common Materials". Retrieved 2007-06-24.

- Farzana, Abanty (2001). "Temperature of a Healthy Human (Skin Temperature)". The Physics Factbook. Retrieved 2007-06-24.

- Lee, B. "Theoretical Prediction and Measurement of the Fabric Surface Apparent Temperature in a Simulated Man/Fabric/Environment System" (PDF). Retrieved 2007-06-24.

- Harris J, Benedict F (1918). "A Biometric Study of Human Basal Metabolism". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 4 (12): 370–3. doi:10.1073/pnas.4.12.370. PMC 1091498. PMID 16576330.

- Levine, J (2004). "Nonexercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT): environment and biology". Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 286 (5): E675 – E685. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.00562.2003. PMID 15102614.

- DrPhysics.com. "Heat Transfer and the Human Body". Retrieved 2007-06-24.

- ^ Cole, George H. A.; Woolfson, Michael M. (2002). Planetary Science: The Science of Planets Around Stars (1st ed.). Institute of Physics Publishing. pp. 36–37, 380–382. ISBN 0-7503-0815-X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ NASA Sun Fact Sheet

- Saari, J. M.; Shorthill, R. W. (1972). "The Sunlit Lunar Surface. I. Albedo Studies and Full Moon". The Moon. 5 (1–2): 161–178. doi:10.1007/BF00562111.

- Lunar and Planetary Science XXXVII (2006) 2406

- Michael D. Papagiannis (1972). Space physics and space astronomy. Taylor & Francis. pp. 10–11. ISBN 9780677040004.

- Willem Jozef Meine Martens and Jan Rotmans (1999). Climate Change an Integrated Perspective. Springer. pp. 52–55. ISBN 9780792359968.

- F. Selsis (2004). "The Prebiotic Atmosphere of the Earth". In Pascale Ehrenfreund; et al. (eds.). Astrobiology: Future Perspectives. Springer. pp. 279–280. ISBN 9781402025877.

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|editor=(help) - The Doppler Effect, T. P. Gill, Logos Press, 1965

- McKinley, John M. (1979). "Relativistic transformations of light power". American Journal of Physics. 47: 602. doi:10.1119/1.11762.

Other textbooks

- Kroemer, Herbert; Kittel, Charles (1980). Thermal Physics (2nd ed.). W. H. Freeman Company. ISBN 0716710889.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Tipler, Paul; Llewellyn, Ralph (2002). Modern Physics (4th ed.). W. H. Freeman. ISBN 0716743450.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

- Calculating Blackbody Radiation Interactive calculator with Doppler Effect. Includes most systems of units.

- Cooling Mechanisms for Human Body - From Hyperphysics

- Descriptions of radiation emitted by many different objects

- BlackBody Emission Applet

- "Blackbody Spectrum" by Jeff Bryant, Wolfram Demonstrations Project, 2007.

- Carbon Nanotube Black Body (AIST nano tech 2009)

, it is a function only of the temperature:

, it is a function only of the temperature:

.

.

.

. .

. .

.

is the

is the  is the surface temperature of the Sun, and

is the surface temperature of the Sun, and is the radius of the Sun.

is the radius of the Sun.

is the radius of the Earth and

is the radius of the Earth and is the

is the  of this energy where

of this energy where  of the sun's light, and reflects the rest. The power absorbed by the Earth and its atmosphere is then:

of the sun's light, and reflects the rest. The power absorbed by the Earth and its atmosphere is then:

, it emits equally in all directions as a sphere. If the Earth were a perfect black body, it would emit according to the Stephan-Boltzmann law

, it emits equally in all directions as a sphere. If the Earth were a perfect black body, it would emit according to the Stephan-Boltzmann law

is the temperature of the Earth. The Earth, since it is at a much lower temperature than the sun, emits mostly in the infrared (IR) portion of the spectrum. In this frequency range, it emits

is the temperature of the Earth. The Earth, since it is at a much lower temperature than the sun, emits mostly in the infrared (IR) portion of the spectrum. In this frequency range, it emits  of the radiation that a black body would emit where

of the radiation that a black body would emit where

254.356 K or -18.8 C.

254.356 K or -18.8 C.